冰冻胚胎移植子代幼儿的体格和神经认知发育评估

董则含,吴琰婷,刘 含,王尹瑜,黄荷凤

上海交通大学医学院附属国际和平妇幼保健院辅助生殖科,上海胚胎源性疾病重点实验室,上海 200030

冰冻胚胎移植(frozen embryo transfer,FET)是一项在体外冷冻和保存胚胎,待解冻后再移植回子宫的技术。自1983 年第一例FET 妊娠出现以来[1],由于其能显著提高累计妊娠率,减少多胎妊娠和卵巢过度刺激综合征的发生[2],且伴随着选择性单胚胎移植技术的迅速发展,其已成为了一种重要的辅助生殖技术(assisted reproductive technology,ART)。目前,全世界已有800 多万名新生儿通过ART 诞生[3]。欧洲人类生殖与胚胎协会报道,2015年FET 周期数目占ART 周期总数的25.7%,并且持续上升[4-5]。多项meta 分析[6-7]显示,FET 与大于胎龄儿(large for gestational age,LGA)、妊娠期高血压的风险增加显著相关。一项基于丹麦人群的大型队列研究[8]提示,与自然受孕(natural conception,NC)诞生的子代相比,经FET 技术诞生的子代在儿童期的癌症风险有显著增加(HR=2.43,95%CI 1.44 ~4.11)。目前关于FET 子代的远期健康和发育的报道相对较少[9],FET 对幼儿的潜在生长发育影响亦尚待评估。

幼儿的神经认知发育受到许多出生前事件和环境因素的影响[10]。出生后到学龄前期是人类神经系统发育的高峰期,发育迟缓或落后在幼儿时期即可出现,会显著影响子代的生活质量,并对后续发育和智力产生损害。已有调查[11]显示,全球约有2.5 亿小于5 岁的幼儿存在智力和行为等发育异常或发育不良的风险。目前,就FET 子代的心理、神经发育方面的研究较少,且存在方法学、研究对象异质性等多方面的局限[3,12]。值得注意的是,在FET 子代中LGA 发生率增加,且子代LGA 在学龄期发生超重和肥胖的比例显著增高[13],这可能与接受FET 的妇女在孕期更易发生胎盘功能障碍有关[14]。多项研究[15-17]提示从儿童到成年期,肥胖和胰岛素抵抗代谢紊乱对认知行为功能存在不良影响。一项西班牙的小样本队列研究[3]提示,FET 与其子代3 岁以下的语言发育迟缓有关。综上,FET 对子代体格、代谢和认知可能存在潜在的不良影响且不容易忽视。基于此,本研究测量FET 子代的体格发育,并使用格塞尔婴幼儿发展量表(Gesell Developmental Schedule,GDS)中文版对FET 子代的适应性、语言、社交等多方面神经认知及行为发育进行评估。鉴于早期干预可以使发育边缘和轻度落后的幼儿恢复良好[18],本研究纳入对象均为幼儿(4 岁以下),以探索可能的早期筛查和干预时机。

1 对象与方法

1.1 研究对象

本研究为双向队列研究。根据接受ART 治疗父母的回顾性信息,于2018 年9 月—2019 年11 月在上海交通大学医学院附属国际和平妇幼保健院招募已接受FET以及NC 出生的幼儿248 名进行研究并随访。纳入标准:① 单胎,妊娠≥28 周。②1.5 ~4 岁。③定期到医院儿保科参加常规体检。排除标准:①母亲有严重的肝肾功能障碍、糖尿病、癌症或自身免疫系统疾病史。② 妊娠前父母至少有一方的体质量指数(body mass index,BMI) >40[19]。③ 出生时诊断为严重的先天性畸形[20],染色体异常或先天代谢性疾病。④心脏或神经系统感染疾病。

本研究获得上海交通大学医学院附属国际和平妇幼保健院伦理委员会审批(伦理批号为GKLW2016-21)。所有监护人均签署知情同意书。

1.2 方法

1.2.1 体外受精胚胎移植 基于母亲的年龄、不孕症的诊断和外周血中窦卵泡个数和抗苗勒激素的浓度水平选择促排卵方案。控制性促排卵(controlled ovarian stimulation,COS)方案包括标准长方案、短方案、拮抗剂等传统方案,以及微刺激方案、个体化联合方案等个体化治疗的新方案[21-24]。人绒毛膜促性腺激素(human chorionic gonadotropin,HCG)注射后34 ~36 h 取卵。使用体外受精或卵细胞质内单精子注射(intra cytoplasmic sperm injection,ICSI)的常规方法使卵母细胞受精[2]。正常受精卵在培养基中培养至卵裂期(第2 日或第3 日)或囊胚期(第5 日或第6 日)后进行冷冻[25],胚胎在雌二醇水平和子宫内膜厚度适宜的当天解冻,并进行移植。

1.2.2 神经认知及行为发育评估 幼儿的神经行为发育为主要结局。FET 组和NC 对照组的神经认知及行为发育水平通过国际统一的GDS 中文版[26]进行评估。GDS 为经典的学龄前儿童神经行为发育评估量表,常用于评估幼儿的神经认知及行为发育[27-28]。结果以神经运动/认知能区5 个方面的发育商(development quotient,DQ)得分来表示,包括粗大运动、精细运动、适应性行为、语言、社交能力。以正常行为模式为标准,鉴定观察到的行为模式,DQ 计算公式:[检测到的年龄(月) /实际年龄(月)]×100。DQ 得分≥85 分为正常发育,75 ~84 分表示可疑神经认知发育迟缓或发育边缘,<75 表示发育迟缓[27]。

1.2.3 体格测评 幼儿体格发育为次要结局。由经过培训的专业医师按照WHO 的操作规范,对随访幼儿进行体检,测量幼儿的身高及体质量。依据WHO 发布的幼儿生长发育曲线参考值及评价标准[27],采用Anthro3.2.2 软件计算相应体格Z 评分。幼儿的体格Z 评分= (实测值-参考值中位数)/标准差,包括年龄别身高/身长(H/LAZ)、年龄别体质量(WAZ)、身高/身长别体质量(WH/LZ)、年龄别体质量指数(BMIZ)。进一步将各变量的Z 评分转化为有临床意义的分类变量,来反映幼儿体格生长发育的不同水平。H/LAZ<-2 定义为矮小,WAZ<-2 定义为消瘦(包括严重消瘦)。WHZ/BMIZ<-2 为营养不良,-2 ~2 为正常,>2 为超重和肥胖[29]。

1.2.4 信息采集 与幼儿的神经行为发育结局相关的协变量较多,持续存在于母亲孕前到子代的幼儿阶段,如父母年龄[30]、子代早产和低出生体质量[31]、母亲妊娠亚甲状腺功能紊乱[32]、父母吸烟[33]、幼儿营养和微量元素补充[34]、乙肝[27,35-36]、母亲孕期环境污染及有害粉尘暴露[37]、母乳喂养[38-39]。通过电子问卷采集母亲孕育史、孕期信息、出生结局和父母家庭环境等社会人口学信息。通过病例资料收集父母既往史,孕前到出生以及体外受精治疗的相关信息。

1.3 统计学方法

采用SPSS 25.0 软件对研究数据进行统计分析。研究对象的基线信息及幼儿发育结局资料中,符合正态分布的定量资料以±s 表示,采用t 检验进行分析;不符合正态分布的定量资料以M(Q1,Q3)表示,采用Mann-Whitney U 检验进行分析。定性资料以频数和百分率表示,采用χ2检验或Fisher 精确检验进行分析。采用向前似然比检验(forward-likelihood ratio,forward-LRT)筛选变量,得到优化后的多元Logistic 回归模型,评估FET 对子代幼儿神经认知发育的影响。P<0.05 表示差异有统计学 意义。

2 结果

2.1 基线特征

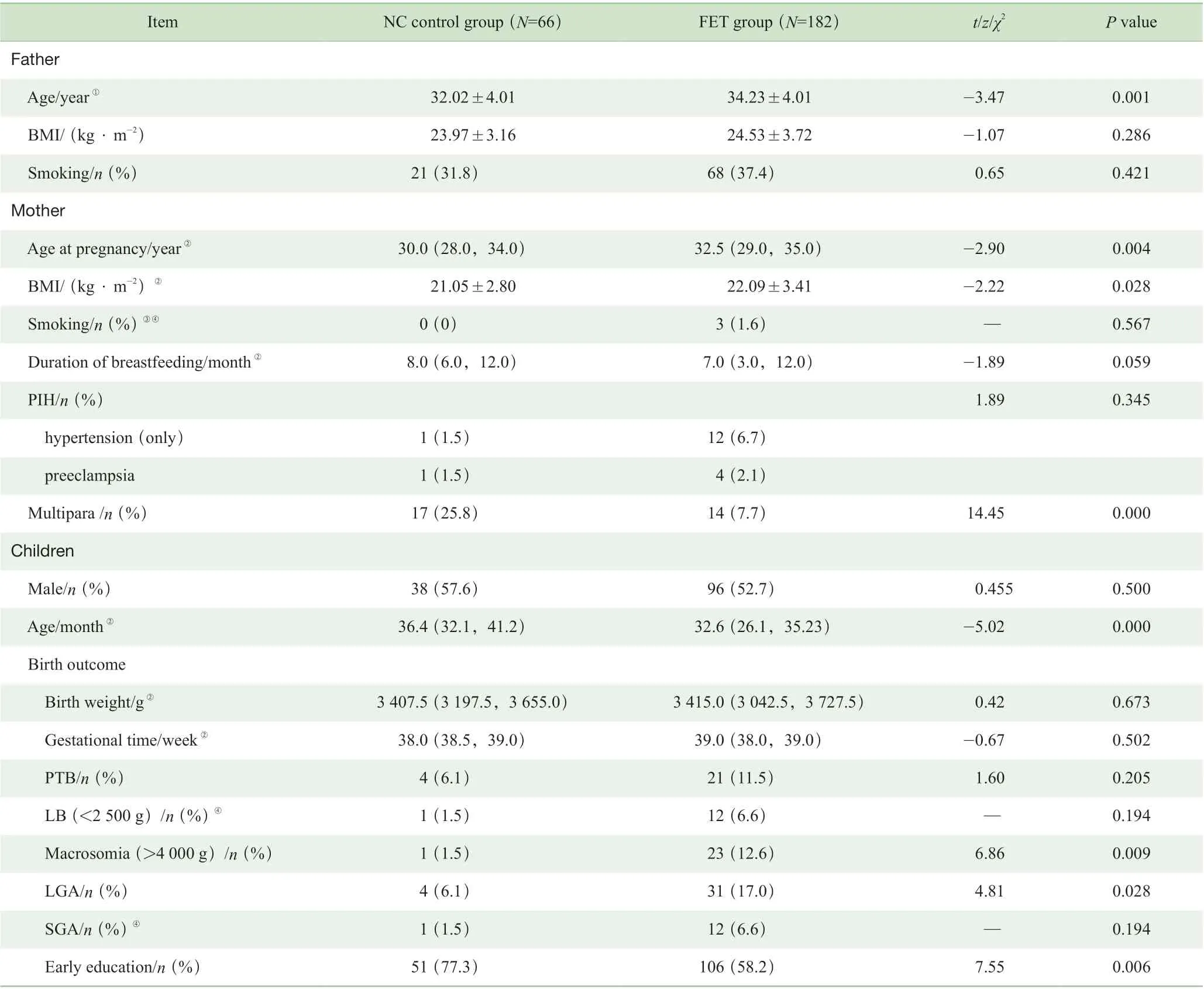

研究队列的基线特征见表1,在248 例幼儿中,FET组182 例,NC 对照组66 例。2 组男女比例近似1:1,其出生体质量和孕周间差异均无统计学意义,但FET 组LGA 和巨大儿的比例更高(P=0.028,P=0.009)。

表1 FET 组和NC 对照组幼儿及父母的基线特征Tab 1 Baseline characteristics of infants and their parents in the FET group and the NC control group

2.2 认知和体格发育水平

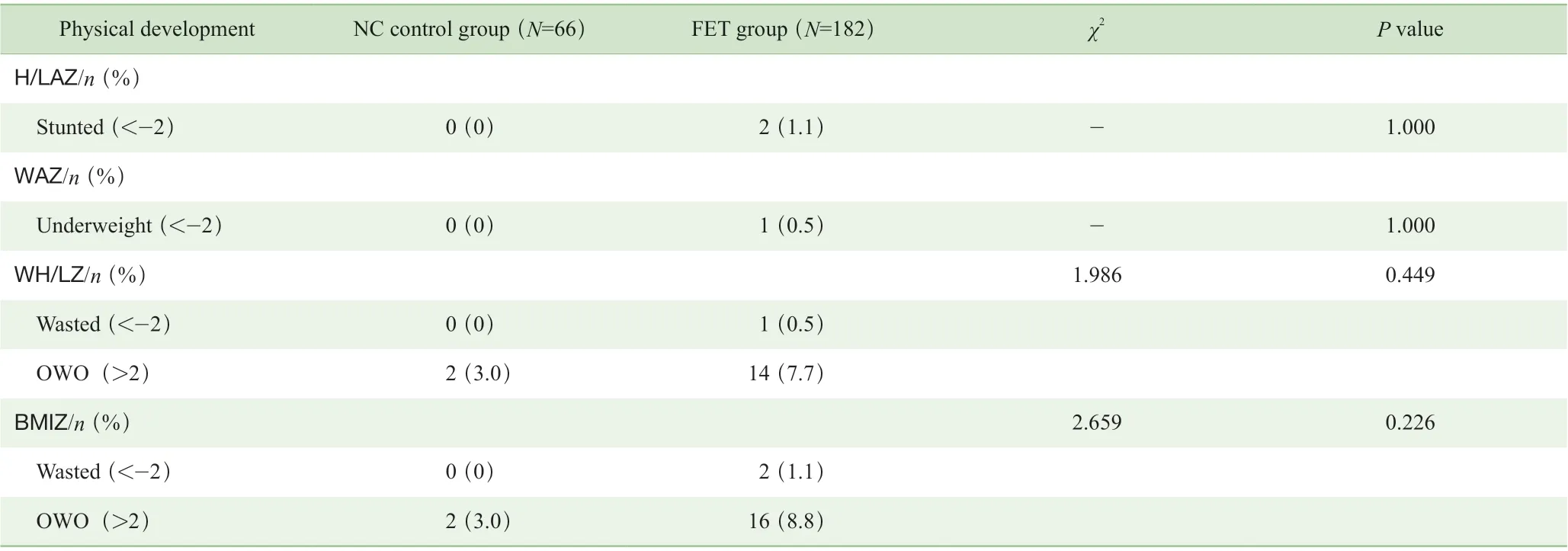

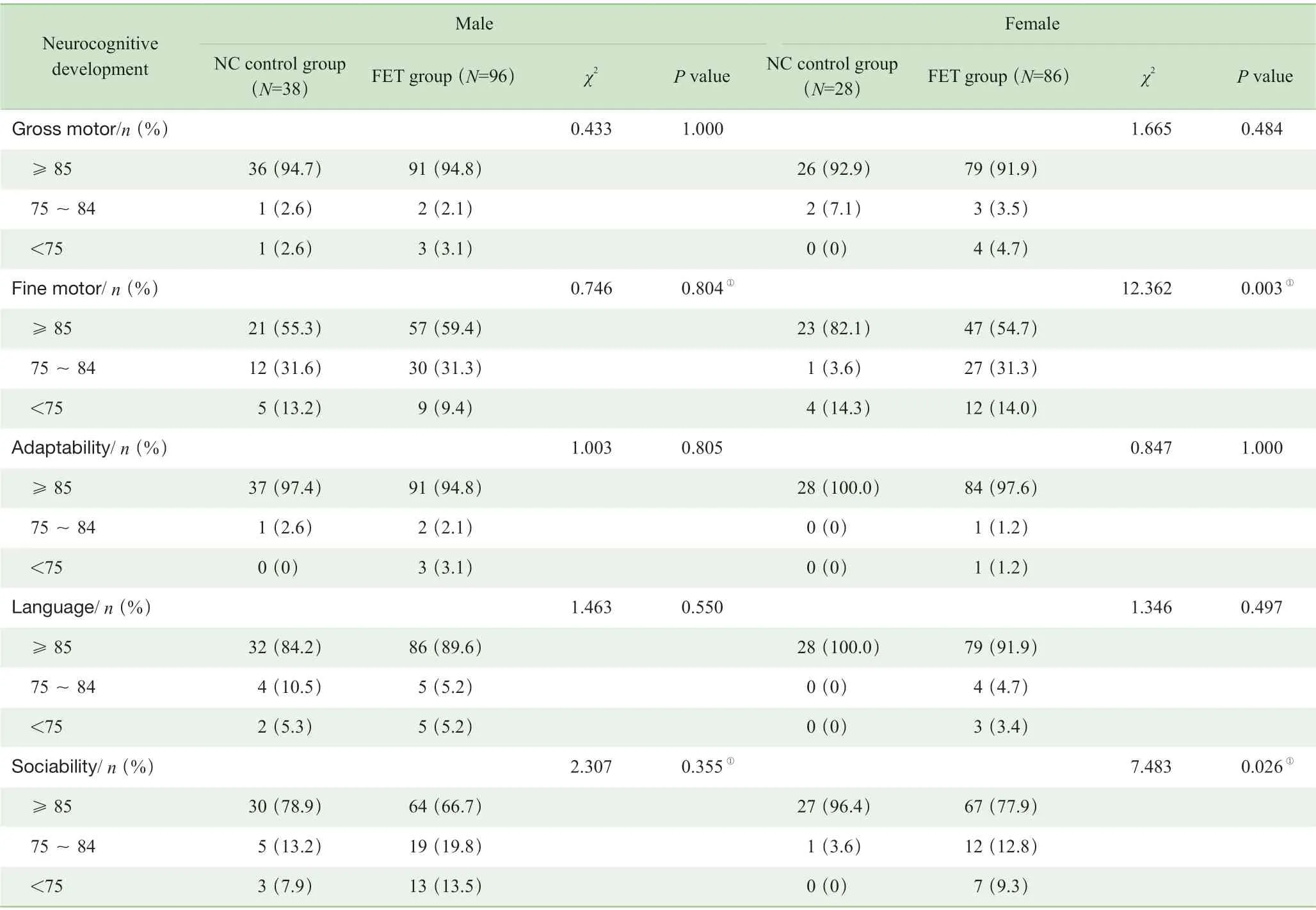

结果(表2、表3)显示,2 组幼儿的各项Z 评分构成比间差异均无统计学意义,提示体格发育水平相似;而 2 组在认知结局方面特别是FET 组中女性子代在精细运动和社交能力的发育水平与NC 组相比,差异均具有统计学意义(P=0.003,P=0.026)。此外,女性子代群体中,仅FET 组出现粗大运动、适应性行为、语言、社交能力的发育迟缓,分别占比为4.7%、1.2%、3.4%和9.3%。

表2 2 组幼儿体格发育的比较Tab 2 Comparison of physical development between the two groups

表3 2 组幼儿神经认知和行为发育比较Tab 3 Comparison of neurocognitive and behavioral development between the two groups

2.3 FET 组子代早期的认知发育不良风险

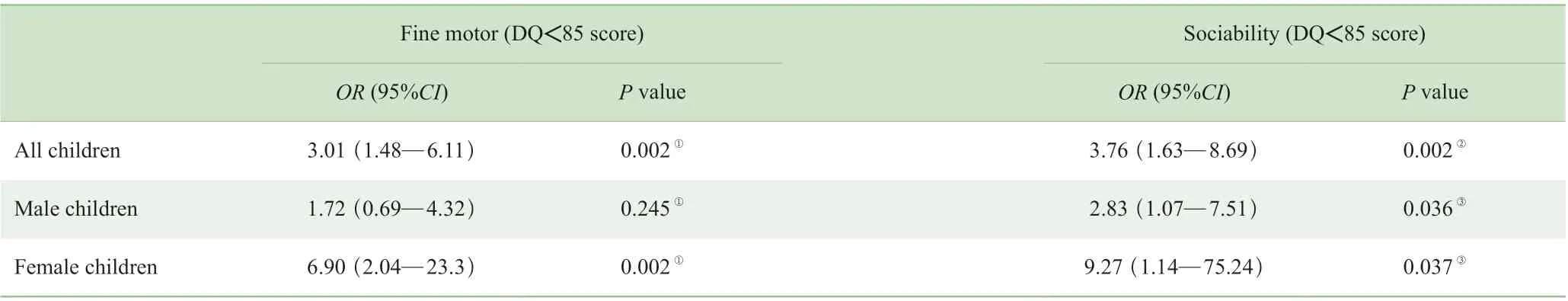

通过多元Logistic 逐步回归分析调整协变量并优化,结果见表4。FET 组幼儿的精细运动和社交能力均存在显著增加其发育异常和迟缓的风险(均P=0.002);当对性别进行单独评估时,结果显示FET 女性子代的精细运动以及男女的社交能力发育均存在显著增加其发育不良或发育迟缓的风险(均P<0.05),且女性比男性的相对风险 更高。

表4 亚组中FET 对子代幼儿神经认知发育异常和迟缓的影响的多元Logistic 回归分析Tab 4 Effects of FET on neurocognitive development abnormality and retardation of offspring in the subgroups by multiple Logistic regression analysis

3 讨论

本研究对2 组幼儿的神经认知发育进行比较,结果显示其主要发育水平间差异具有统计学意义,特别是子代女性的精细运动和社交能力方面(P=0.003,P=0.026)。多元Logistic 回归分析验证了FET 对子代女性的不良影响;此外,FET 对子代男性的社交发育的不良影响也有统计学意义,但比女孩相对低。英国的一项研究[40]招募了91 名经FET 诞生的幼儿和83 名NC 诞生的幼儿,2 组在幼儿期的神经行为和认知发育水平间差异无统计学意义,但玻璃化冷冻胚胎合并先天畸形的神经运动评分较低。另一项瑞典的研究[41]随访了FET、NC 和新鲜胚胎移植诞生的子代,神经发育紊乱性疾病仅出现在FET 组中,患病人数为3(1.2%)。另有研究[3]提示,FET 与子代3 岁以下婴幼儿的语言发育迟缓相关,语言与社交能力相互影响,可能根据幼儿特征先后出现。这与我们的研究结果类似,提示FET 本身或过程中或存在与社交能力发育独立相关的风险因素,可能的中间机制之一即是FET 增加了巨大儿、LGA、妊娠高血压、子痫、胎盘血管病变异常的风险[6-7,42]。已有研究[43]提示先兆子痫与子代智力异常高度相关,且从本研究结果可见FET 组孕期妊娠高血压/子痫前期的比例均高于NC 对照组。此外,一项队列研究[44]提示,与传统体外受精新鲜胚胎移植组相比,冰冻胚胎移植卵胞浆内单精子显微注射(intracytoplasmic sperm injection,ICSI)组与新鲜胚胎移植ICSI 组子代的神经认知发育迟缓风险均显著增高,冰冻胚胎移植ICSI 组的风险明显更高,因此FET 特有的冻融程序或可对子代精神和认知发育存在不良影响,特别是ICSI 因素存在的情况下,可能与其产生了交互作用。

在分子机制和遗传水平上,认知发育风险增加可能的原因之一是与ART 相关体外操作通过改变基因印记或表观遗传对后期胚胎及子代发育产生影响[42,45-46]。研究[47]表明,体外受精可以改变新生儿血液中特定基因组的甲基化,而新生儿的基因组甲基化处于亚稳态状态,因此对某些表观基因组将存在持久的影响。大量的动物实验表明,胚胎植入前的体外培养和操作[48-50]、FET 冻融程序[51]与子代的远期生长发育、神经行为受损、体质量、代谢紊乱风险相关,而这些不利因素都可能影响FET 子代的神经认知和生长发育。此外,Sun 等[52]的研究表明,人类卵裂球胚胎解冻后再培养一段时间,可发现明显增高的多核发生率,且远高于新鲜胚胎移植。Seikkula 等[53]的病例对照研究则纳入多核或双核冰冻胚胎移植周期的妇女和子代作为病例组,病例组的临床妊娠率和活产率与正常组相比都显著降低,提示FET 组的多核胚胎发生对后续胚胎发育和子代发育具有潜在的不良影响。

子代早期的认知发育对后期成长有很大影响[54],大脑在婴幼儿时期具有很强的可塑性,对神经认知发育轻度迟缓或边缘状态的幼儿进行积极的早期干预,可能将获得较理想的效果[18]。因此,建议在发育早期即婴幼儿时期,密切关注FET 子代的社交行为以及子代女性的精细运动等神经认知发育情况,必要时进行早期筛查和干预。有研究[38]表明延长母乳喂养对幼儿的认知行为发育是一个独立保护因素,而接受ART 的母亲的母乳喂养水平普遍低下[55],因此促进母乳喂养或可帮助子代幼儿改善、恢复和实现追赶生长。

本研究结果显示,FET 组与NC 组的子代在小于4岁的幼儿时期,其体格发育水平相似,但FET 子代在精细运动和社交能力发育迟缓的风险增加;虽然在多元Logistic 回归分析时校正了幼儿早教这一潜在混杂因素,但并不能排除父母过度保护、育儿意识欠缺的混杂以及家庭的潜在选择偏倚。由于本研究样本量较小,可能存在一定的局限性和偏倚,鉴于幼儿时期认知发育对生活质量和后续认知发育的持续影响,将来可增加样本量并延长随访时间,对上述研究结果做进一步的验证。

参·考·文·献

[1] Trounson A, Mohr L. Human pregnancy following cryopreservation, thawing and transfer of an eight-cell embryo[J]. Nature, 1983, 305(5936): 707-709.

[2] Belva F, Henriet S, van den Abbeel E, et al. Neonatal outcome of 937 children born after transfer of cryopreserved embryos obtained by ICSI and IVF and comparison with outcome data of fresh ICSI and IVF cycles[J]. Hum Reprod, 2008, 23(10): 2227-2238.

[3] Sánchez-Soler MJ, López-González V, Ballesta-Martínez MJ, et al. Assessment of psychomotor development of Spanish children up to 3 years of age conceived by assisted reproductive techniques: prospective matched cohort study[J]. An Pediatr (Barc), 2020, 92(4): 200-207.

[4] De Geyter C, Calhaz-Jorge C, Kupka MS, et al. ART in Europe, 2014: results generated from European registries by ESHRE: the European IVF-monitoring consortium (EIM) for the European society of human reproduction and embryology (ESHRE)[J]. Hum Reprod, 2018, 33(9): 1586-1601.

[5] De Geyter C, Calhaz-Jorge C, Kupka MS, et al. ART in Europe, 2015: results generated from European registries by ESHRE[J]. Hum Reprod Open, 2020, 2020(1): hoz038.

[6] Maheshwari A, Pandey S, Amalraj Raja E, et al. Is frozen embryo transfer better for mothers and babies? Can cumulative meta-analysis provide a definitive answer?[J]. Hum Reprod Update, 2018, 24(1): 35-58.

[7] Sha TT, Yin XQ, Cheng WW, et al. Pregnancy-related complications and perinatal outcomes resulting from transfer of cryopreserved versus fresh embryos in vitro fertilization: a meta-analysis[J]. Fertil Steril, 2018, 109(2): 330-342. E9.

[8] Hargreave M, Jensen A, Hansen MK, et al. Association between fertility treatment and cancer risk in children[J]. JAMA, 2019, 322(22): 2203-2210.

[9] Wennerholm UB, Söderström-Anttila V, Bergh C, et al. Children born after cryopreservation of embryos or oocytes: a systematic review of outcome data[J]. Hum Reprod, 2009, 24(9): 2158-2172.

[10] Bloomfield FH. Epigenetic modifications may play a role in the developmental consequences of early life events[J]. J Neurodev Disord, 2011, 3(4): 348-355.

[11] Black MM, Walker SP, Fernald LCH, et al. Early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course[J]. Lancet, 2017, 389(10064): 77-90.

[12] Hart R, Norman RJ. The longer-term health outcomes for children born as a result of IVF treatment. Part Ⅱ : mental health and development outcomes[J]. Hum Reprod Update, 2013, 19(3): 244-250.

[13] Zhou J, Zeng LX, Wang DL, et al. Effects of birth weight on body composition and overweight/obesity at early school age[J]. Clin Nutr, 2020, 39(6): 1778-1784.

[14] Peng SN, Deyssenroth MA, Di Narzo AF, et al. Genetic regulation of the placental transcriptome underlies birth weight and risk of childhood obesity[J]. PLoS Genet, 2018, 14(12): E1007799.

[15] Singh-Manoux A, Czernichow S, Elbaz A, et al. Obesity phenotypes in midlife and cognition in early old age: the Whitehall Ⅱ cohort study[J]. Neurology, 2012, 79(8): 755-762.

[16] Martin A, Booth JN, Laird Y, et al. Physical activity, diet and other behavioural interventions for improving cognition and school achievement in children and adolescents with obesity or overweight[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2018. 3: CD009728.

[17] Wodschow HZ, Jensen NJ, Desirée Nilsson MS, et al. The effect of hyper- and hypoglycaemia on cognition and development of dementia for patients with diabetes mellitus Type 2[J]. Ugeskr Laeg, 2018, 180(51): V08180566.

[18] Ros R, Hernandez J, Graziano PA, et al. Parent training for children with or at risk for developmental delay: the role of parental homework completion[J]. Behav Ther, 2016, 47(1): 1-13.

[19] Cedergren MI. Maternal morbid obesity and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcome[J]. Obstet Gynecol, 2004, 103(2): 219-224.

[20] Reis M, Källén B. Combined use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and sedatives/hypnotics during pregnancy: risk of relatively severe congenital malformations or cardiac defects. A register study[J]. BMJ Open, 2013, 3(2): E002166.

[21] Chatillon-Boissier K, Genod A, Denis-Belicard E, et al. Prospective randomised study of long versus short agonist protocol with poor responder patients during in vitro fertilization[J]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil, 2012, 40(11): 652-657.

[22] Pacchiarotti A, Selman H, Valeri C, et al. Ovarian stimulation protocol in IVF: an up-to-date review of the literature[J]. Curr Pharm Biotechnol, 2016, 17(4): 303-315.

[23] La Marca A, Sunkara SK. Individualization of controlled ovarian stimulation in IVF using ovarian reserve markers: from theory to practice[J]. Hum Reprod Update, 2014, 20(1): 124-140.

[24] Nargund G, Datta AK, Fauser BCJM. Mild stimulation for in vitro fertilization[J]. Fertil Steril, 2017, 108(4): 558-567.

[25] Larman MG, Minasi MG, Rienzi L, et al. Maintenance of the meiotic spindle during vitrification in human and mouse oocytes[J]. Reprod Biomed Online, 2007, 15(6): 692-700.

[26] You J, Shamsi BH, Hao MC, et al. A study on the neurodevelopment outcomes of late preterm infants[J]. BMC Neurol, 2019, 19(1): 108.

[27] Zeng HH, Cai HD, Wang Y, et al. Growth and development of children prenatally exposed to telbivudine administered for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B in their mothers[J]. Int J Infect Dis, 2015, 33: 97-103.

[28] Marques RC, Garrofe Dórea J, Rodrigues Bastos W, et al. Maternal mercury exposure and neuro-motor development in breastfed infants from Porto Velho (Amazon), Brazil[J]. Int J Hyg Environ Health, 2007, 210(1): 51-60.

[29] World Health Organization. Growth problems[EB/OL]. (2020-04-12)[2020-04-26]. https: //www.who.int/childgrowth/training/module_c_interpreting_indicators.

[30] Merikangas AK, Calkins ME, Bilker WB, et al. Parental age and offspring psychopathology in the Philadelphia neurodevelopmental cohort[J]. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 2017, 56(5): 391-400.

[31] Zavadenko NN, Davydova LA. Neurological and neurodevelopmental disorders in preterm-born children (with extremely low, very low or low body weight)[J]. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova, 2019, 119(12): 12-19.

[32] Nattero-Chávez L, Luque-Ramírez M, Escobar-Morreale HF. Systemic endocrinopathies (thyroid conditions and diabetes): impact on postnatal life of the offspring[J]. Fertil Steril, 2019, 111(6): 1076-1091.

[33] Banderali G, Martelli A, Landi M, et al. Short and long term health effects of parental tobacco smoking during pregnancy and lactation: a descriptive review[J]. J Transl Med, 2015, 13: 327.

[34] Chen K, Zhang X, Wei XP, et al. Antioxidant vitamin status during pregnancy in relation to cognitive development in the first two years of life[J]. Early Hum Dev, 2009, 85(7): 421-427.

[35] Karlsson H, Dalman C. Epidemiological studies of prenatal and childhood infection and schizophrenia[J]. Curr Top Behav Neurosci, 2020, 44: 35-47.

[36] Lee YH, Papandonatos GD, Savitz DA, et al. Effects of prenatal bacterial infection on cognitive performance in early childhood[J]. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol, 2020, 34(1): 70-79.

[37] Lee J, Kalia V, Perera F, et al. Prenatal airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure, LINE1 methylation and child development in a Chinese cohort[J]. Environ Int, 2017, 99: 315-320.

[38] Heikkilä K, Sacker A, Kelly Y, et al. Breast feeding and child behaviour in the Millennium Cohort Study[J]. Arch Dis Child, 2011, 96(7): 635-642.

[39] Pang WW, Tan PT, Cai SR, et al. Nutrients or nursing? Understanding how breast milk feeding affects child cognition[J]. Eur J Nutr, 2020, 59(2): 609-619.

[40] Sutcliffe AG, D'Souza SW, Cadman J, et al. Minor congenital anomalies, major congenital malformations and development in children conceived from cryopreserved embryos[J]. Hum Reprod, 1995, 10(12): 3332-3337.

[41] Wennerholm UB, Albertsson-Wikland K, Bergh C, et al. Postnatal growth and health in children born after cryopreservation as embryos[J]. Lancet, 1998, 351(9109): 1085-1090.

[42] Bowdin S, Allen C, Kirby G, et al. A survey of assisted reproductive technology births and imprinting disorders[J]. Hum Reprod, 2007, 22(12): 3237-3240.

[43] Figueiró-Filho EA, Mak LE, Reynolds JN, et al. Neurological function in children born to preeclamptic and hypertensive mothers: a systematic review[J]. Pregnancy Hypertens, 2017, 10: 1-6.

[44] Sandin S, Nygren KG, Iliadou A, et al. Autism and mental retardation among offspring born after in vitro fertilization[J]. JAMA, 2013, 310(1): 75-84.

[45] Rivera RM, Stein P, Weaver JR, et al. Manipulations of mouse embryos prior to implantation result in aberrant expression of imprinted genes on day 9.5 of development[J]. Hum Mol Genet, 2008, 17(1): 1-14.

[46] Nelissen EC, Dumoulin JC, Daunay A, et al. Placentas from pregnancies conceived by IVF/ICSI have a reduced DNA methylation level at the H19 and MEST differentially methylated regions[J]. Hum Reprod, 2013, 28(4): 1117-1126.

[47] Estill MS, Bolnick JM, Waterland RA, et al. Assisted reproductive technology alters deoxyribonucleic acid methylation profiles in bloodspots of newborn infants[J]. Fertil Steril, 2016, 106(3): 629-639. E10.

[48] Ecker DJ, Stein P, Xu Z, et al. Long-term effects of culture of preimplantation mouse embryos on behavior[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2004, 101(6): 1595-1600.

[49] Khosla S, Dean W, Reik W, et al. Culture of preimplantation embryos and its long-term effects on gene expression and phenotype[J]. Hum Reprod Update, 2001, 7(4): 419-427.

[50] Calle A, Fernandez-Gonzalez R, Ramos-Ibeas P, et al. Long-term and transgenerational effects of in vitro culture on mouse embryos[J]. Theriogenology, 2012, 77(4): 785-793.

[51] Dulioust E, Toyama K, Busnel MC, et al. Long-term effects of embryo freezing in mice[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1995, 92(2): 589-593.

[52] Sun L, Chen ZH, Yang L, et al. Chromosomal polymorphisms are independently associated with multinucleated embryo formation[J]. J Assist Reprod Genet, 2018, 35(1): 149-156.

[53] Seikkula J, Oksjoki S, Hurme S, et al. Pregnancy and perinatal outcomes after transfer of binucleated or multinucleated frozen-thawed embryos: a case-control study[J]. Reptod Biomed Online, 2018, 36(6): 607-613.

[54] Paavola LE, Remes AM, Harila MJ, et al. A 13-year follow-up of Finnish patients with Salla disease[J]. J Neurodev Disord, 2015, 7(1): 20.

[55] Cromi A, Serati M, Candeloro I, et al. Assisted reproductive technology and breastfeeding outcomes: a case-control study[J]. Fertil Steril, 2015, 103(1): 89-94.