运动干预改善帕金森病运动症状及可能机制的研究进展*

陈 平, 乔德才, 刘晓莉

(1北京师范大学体育与运动学院, 北京 100875; 2吕梁学院体育系, 山西 吕梁 033000 )

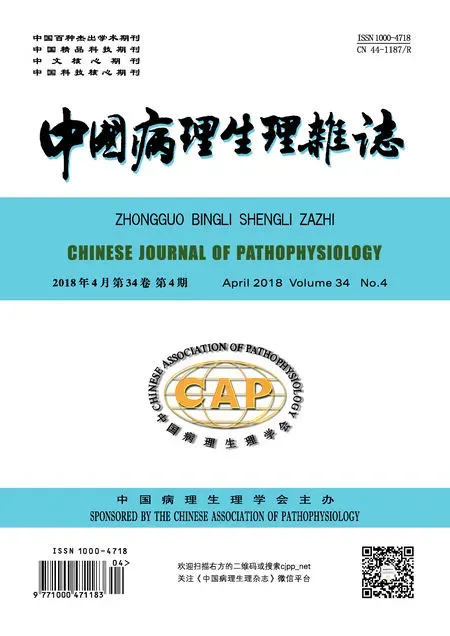

帕金森病(Parkinson disease,PD),又名震颤麻痹(paralysis agitants),由英国医师James Parkinson(1817年)在他的《震颤麻痹分析》(Essayon the shaking palsy)一文中首先描述[1],被认为是第二大与年龄相关的、以中脑黑质多巴胺(dopamine,DA)能神经元丢失导致纹状体DA递质减少为特征的渐进性、不可逆转性神经功能障碍性疾病[2-3],堪称是继肿瘤和心脑血管病之后中老年的“第三杀手”[4]。PD的神经病理学特征为中脑黑质DA能神经元变性丢失和残存神经元胞浆内嗜酸性包涵体路易小体(包含α-突触核蛋白和泛素化)形成,导致黑质-纹状体通路DA释放减少(图1[5]),从而出现以运动功能障碍(如运动迟缓、肌肉僵直、静止性震颤、步态障碍和身体姿势不稳等)为主要特征的临床综合征,最终导致患者日常生活活动困难和生活质量下降[6]。可用的药理学和神经调节方法虽然缓解了PD的运动障碍症状,但到目前为止,临床上尚无有效手段能够治愈、阻止或者延缓PD的进展。流行病学调查发现,长期的身体活动与PD的低发病率呈高度相关[7];运动具有改善PD患者运动症状的潜力,已被广泛应用于PD临床康复治疗[8-9]。本文就运动干预改善帕金森病运动症状及可能机制进行综述。

1 运动对PD运动症状的改善

PD的主要特征是步态障碍和平衡能力的丧失。在PD中,运动干预通常被用来改善PD患者的步态和平衡功能障碍。

步态障碍包括速度和步长的下降以及步幅长度的增加,并可能影响到个体的生活质量[10]。跑台训练由于易于调整速度(和坡度),从而增加步态练习的强度和挑战性而通常被用来改善PD患者的步态能力。大量研究结果表明,轻度至中度的PD患者经跑台训练后可显著改善他们的步态表现,包括步速、步长、节奏、姿势稳定性、步态节律性和关节移动度[11-14]。另外,跑台训练的这种效益不仅体现在运动完成后的即刻,甚至在停止训练后也长期(持续几个月)保留[15-16]。但也有一些研究表明,跑台训练对PD患者步态能力没有实质性的改善[17],这可能是由于疾病的严重程度不同所导致的。除了跑台训练外,Arcolin等[18]研究表明,PD患者在进行24个月(每周2次)的渐进性抗阻训练干预后,患者的步态速度、节奏、跖屈强度和步长均显著升高;分别对PD患者进行3周循环测功仪训练(cycle ergometer trai-ning)和12周的主动辅助强迫运动训练后, PD患者的步态参数得到显著的改善,表现为步速、步长、摆动相和单支撑相显著升高,足偏角及步宽显著降低,6 min步行测试、平衡测试及起立-行走时间测试得分均显著提高[19-20];对PD患者进行水中体育锻炼后,步态参数显著改善,表现为步行速度、步长、单跨步时间和单双脚支撑时间均显著提高[21-22];Allen等[23]研究表明,6周气功锻炼对PD患者步态功能有益,表现为锻炼后可使PD患者步幅长度、步速显著增加,步态变异性显著改善,特别是单跨步时间变异性显著降低。

Figure 1. Diagrams of basal ganglia-thalamic cortex loop regulation at physiological and PD status[5].

图1生理和PD状态下基底神经节-丘脑皮层环路调控模式图[5]

平衡功能障碍是导致PD个体致残率增加及健康相关的生活质量和生存率降低的主要原因,许多锻炼方式旨在改善PD患者的平衡能力[24]。研究表明,太极拳将缓慢的移动控制、力量、多方向运动,以及需要认知注意的连续复杂动作自然地结合到了一起,通过身体重量移动来控制最大运动期间的重心从而专注于对动态姿势的控制[25]。大量随机对照试验研究表明,太极拳训练对PD患者姿势控制具有有益的影响,并得到了社区PD患者的关注[26]。研究表明,太极拳训练可有效减轻轻度至中度PD患者肢体僵硬程度,改善肢体灵活性,使下肢力量和步幅显著增加,行走速度加快,跌倒频率显著降低,有效改善患者的步态和平衡功能,且这些有益的效用至少保留2个月[27]。

同传统的运动干预方式相比,探戈、华尔兹和狐步舞对PD患者的平衡、步态和耐力均具有显著的促进作用。一项基于社区的随机对照研究发现,同对照组相比,12个月的探戈训练导致PD患者疾病的严重程度(统一帕金森病评定量表得分)显著降低,如日常生活活动、运动迟缓、肌肉僵直、震颤、平衡障碍和双任务行走均得到显著改善;此外,随访时对照组具有更多的冻结步态发生,6 min步行测试恶化,但舞蹈组保持稳定[28];另有研究表明,10周的舞蹈训练可使PD患者平衡和步态障碍得到改善,具体表现为起立-步行计时测试和6 min步行测试得分均显著提高[29]。

拳击是包含多向运动的动态平衡活动。研究表明,12周的拳击训练可使轻度PD患者的平衡、步态、日常生活活动和生活质量显著改善;较长时间(36周)的拳击训练可使中度至重度PD患者显示最大的训练效果[30]。Konerth等[31]研究表明,10周平衡训练可显著改善PD患者的肌肉力量和平衡功能,表现为平衡测试得分显著提高,跌倒次数显著降低,跌倒潜伏期(latency to fall)显著增加,膝关节伸展/屈曲及踝关节伸展力量均显著增加,且这种效果至少持续4周。此外,身体活动与上下楼梯或在不使用手的情况下从无扶手椅子上站立起来所需的时间的减少以及总步行距离的增加显著相关[32];8周多维平衡训练可使PD患者平衡功能和双任务步态表现显著改善,表现为步态速度、平衡评价系统测验总分及各项得分、双重任务起立-行走计时测试得分和特定活动平衡信心量表得分均显著提高,且这种有益效用可持续到12周以后[33]。

综合以上研究,运动/身体锻炼对改善PD患者运动症状或减缓症状的发展具有非常积极的作用。但是,后续的随访评估研究却很少,并且哪种运动方式最适合PD患者也不清楚。因此,各种运动方式之间的对比和运动带来的长期效益仍然需要系统的研究和更多的探索。

2 运动干预改善PD运动症状的可能机制

尽管运动/身体锻炼改善PD运动功能障碍或减缓PD症状发展的结论已在临床和基础研究中都得到了证实,但其潜在机制却存在不同的解释。目前主要有以下两种观点:即运动的神经保护性作用和运动的神经可塑性作用。

2.1运动的神经保护性作用

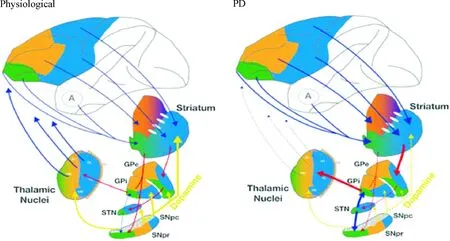

2.1.1运动的抗氧化应激作用 氧化应激(Oxidative stress,OS)是一种以氧化组分含量显著增加为特征的级联反应。氧化应激假说推测细胞高活性氧的产生和抗氧化系统失衡进而导致PD(图2[34])。

Figure 2. Reactive oxygen species and the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease[34]. A: the production of reactive oxygen species; B: the imbalance between production and elimination of reactive oxygen species.

图2活性氧簇和PD的发病机制[34]

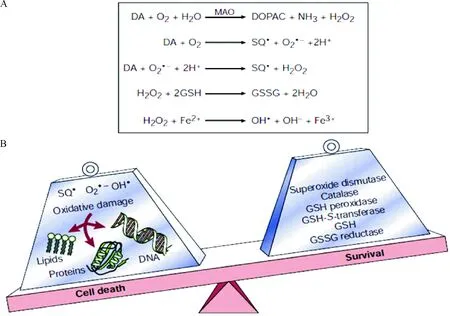

研究表明,PD状态下,中脑黑质DA能神经元处于高氧化应激状态,脂质、蛋白质和DNA氧化的副产物升高,抗氧化系统的代偿性增加[35]。PD患者黑质脂质氧化的标记物丙二醛和脂质过氧化的水平较正常人高10倍[36]。在细胞水平,PD患者黑质残存的DA能神经元内脂质过氧化的主要产物4-羟基壬烯醛的表达量较正常的对照个体显著升高[37]。PD患者黑质DA能神经元DNA和RNA氧化的标记物8-羟基脱氧尿苷显著增加[38]。黑质蛋白质氧化的标志物蛋白质羰基化合物的水平是其它脑区的2倍。黑质中用来清除ROS的抗氧化物质如谷胱甘肽(glutathione,GSH)、超氧化物歧化酶(superoxide dismutase,SOD)、谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶(glutathione peroxidase,GPx)和过氧化氢酶(catalase)等均显著降低,亚铁离子(Fe2+)浓度显著增高[39-40]。针对氧化应激的抗氧化治疗方案是目前治疗PD的重要手段之一,且在实验和临床中取得了一定的疗效。Aguiar等[41]研究表明,6周跑台训练可使6-羟多巴胺(6-hydroxydopamine,6-OHDA)诱导的PD小鼠模型黑质-纹状体DA能神经元丢失减轻,运动功能改善,表现为黑质酪氨酸羟化酶(tyrosine hydroxylase,TH)免疫阳性细胞数量和纹状体TH免疫阳性纤维终末含量显著升高,前肢不对称性测验得分和阿扑吗啡诱导的旋转次数显著降低;参与线粒体生物发生和抗氧化防御酶基因表达水平显著升高,表现为线粒体转录因子、NADH脱氢酶Q1α子复合体亚基6、线粒体复合物Ⅰ、核因子E2相关因子2(nuclear factor E2-related factor 2,Nrf2)和血红素氧合酶1(heme oxygenase-1,HO-1)mRNA表达水平显著升高,线粒体复合物1的活性及线粒体复合物与柠檬酸合酶的比率显著升高,纹状体亚硝酸盐的含量显著降低。Tsou等[42]研究表明,4周跑台训练可使MPTP诱导的PD小鼠模型黑质-纹状体DA能神经元丢失减轻,抗氧化能力增强,表现为黑质TH免疫阳性细胞数量、纹状体TH免疫阳性纤维终末含量及黑质-纹状体TH蛋白表达水平显著升高,纹状体多巴胺转运体、黑质-纹状体总谷胱甘肽含量以及氧化型谷胱甘肽与总谷胱甘肽的比率显著升高,黑质-纹状体Nrf2 mRNA表达水平和γ-谷氨酰半胱氨酸连接酶催化亚基(γ-glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit,γ-GCLC)及HO-1蛋白表达水平显著升高。Nrf2-抗氧化反应元件(antioxidant responsive element,ARE)信号通路是对抗氧化应激的一个重要的细胞防御机制。Nrf2-ARE通路强有力地参与了神经保护和抗炎症反应。研究表明, Nrf2被ROS激活后,与ARE启动子序列结合,从而使ARE包含的基因表达上调,如醌氧化还原酶1、γ-GCLC、谷胱甘肽S-转移酶、HO-1等[43]。大量研究证据表明,利用Nrf2小分子诱导剂或Nrf2基因过表达治疗对脑缺血或者PD模型具有神经保护作用[44]。此外,Nrf2丢失促进MPTP的毒性作用,并能够使α-突触核蛋白过表达,加剧DA能神经元的丢失[45]。这些研究结果表明,运动可能通过Nrf2-ARE信号通路调节抗氧化酶的表达,从而增强机体抗氧化防御系统功能及自由基清除能力,进而在PD中发挥神经保护作用,见图3。

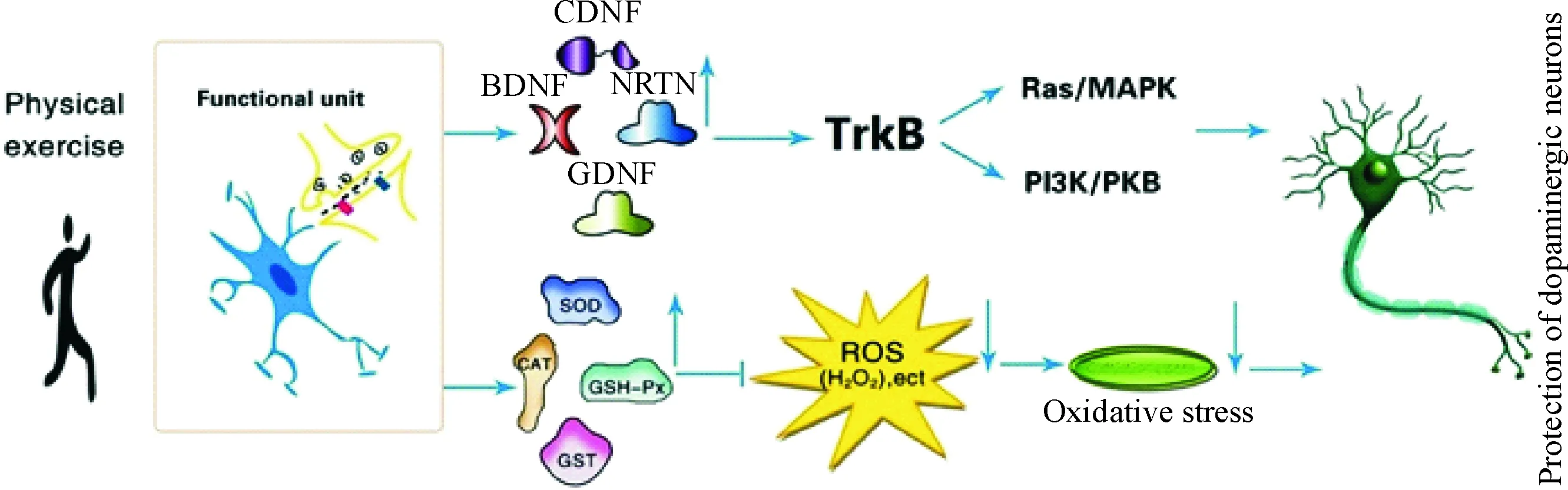

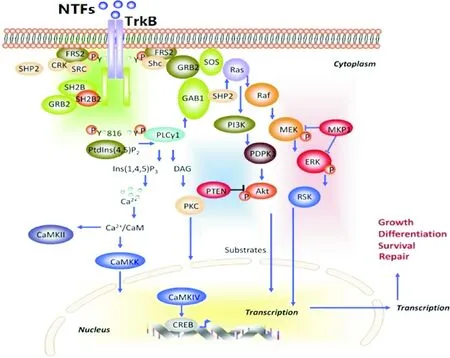

2.1.2运动的神经营养作用 神经营养因子(neurotrophic factors, NTFs) 是机体产生的能够促进神经元发育和正常生理功能的一类蛋白因子,主要包括脑源性神经营养因子(brain-derived neurotrophic factor,BDNF)、胶质细胞源性营养因子(glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor,GDNF)、脑多巴胺神经营养因子(cerebral dopamine neurotrophic factor,CDNF)和神经营养因子3(neurotrophin-3,NF-3)等。这些NTFs通过其高亲和力的共同受体——原肌球蛋白相关激酶B(tropomyosin-related kinase B,TrkB)对神经元的生长、发育、分化、存活、凋亡和损伤后修复进行调节。

Scalzo等[46]研究表明,PD患者血清BDNF浓度显著降低;Tajiri 等[47]和Lau 等[48]研究表明,PD动物模型黑质DA能神经元退行性病变伴随着BDNF表达的显著降低;Nam等[49]研究表明,PD患者黑质致密区残存的DA能神经元BDNF mRNA及蛋白表达水平显著降低,与Howells等[50]和Mogi等[51]对PD患者进行尸检后发现黑质BDNF水平降低的研究结果一致。GDNF是近年来发现的特异性最强的DA能神经元营养因子。Ngema等[52]和Yue等[53]研究表明,伴随着6-OHDA损毁大鼠模型黑质DA能神经元的损伤,黑质纹状体GDNF和NF-3表达显著降低。而早期运动干预可使神经毒素(MPTP和6-OHDA等)诱导的PD动物模型DA能神经元得到保护和修复,这可能是运动通过多途径增加NTFs的表达实现的。Tajiri等[47]和Lau等[48]研究表明,4周跑台训练(5 d/week,30 min/d,11 m/min)或18周递增负荷跑台训练(5 d/week,40 min/d)均可使PD大鼠或小鼠模型黑质-纹状体系统BDNF和GDNF表达显著增加,纹状体TH阳性纤维终末及黑质致密部TH阳性神经元得到显著保护,运动功能显著改善。Jang等[54]和Wu等[55]研究表明,跑台训练可使PD小鼠模型黑质、纹状体BDNF、GDNF及TrkB表达水平显著增高,DA能神经元丢失显著降低,行为功能障碍减轻。而BDNF或者GDNF表达降低(或者消除),TrkB拮抗剂或者TrkB基因敲除可使运动诱导的神经保护作用及运动功能改善消失[56-58]。这些研究结果表明,运动干预可能通过提高NTFs的表达,保护或者减轻神经毒素对PD动物模型DA能神经元的毒性损伤。其机制可能是增加的NTFs通过与其受体TrkB结合,引起TrkB自身磷酸化作用增强,进而直接或者间接触发胞内下游信号传递的级联反应[59],从而促进DA能神经元的存活,见图3、4。

2.2运动的神经可塑性作用 纹状体DA耗竭引起皮层-纹状体谷氨酸(glutamate acid,Glu)能通路过度激活,突触前末梢释放大量的Glu对突触后膜产生兴奋性毒作用是导致PD状态下纹状体一系列病理改变的原因之一。Glu介导的兴奋性毒作用使纹状体MSNs树突棘末梢Ca2+超载,表现为纹状体中型多棘神经元树突棘(medium spiny neurons,MSNs)形态结构的异常改变(如树突棘数量、密度降低和超微结构异常等)以及皮层-纹状体突触连接功能的增强。

William等[60]、Toy等[61]和Shin 等[62]研究发现,4周大强度跑台训练可显著增加PD小鼠模型纹状体树突棘的数量和密度;陈巍等[63]研究发现,4周中等强度跑台训练在显著增加PD大鼠模型纹状体MSNs树突棘数量和密度的同时,显著降低纹状体MSNs不对称性突触中穿通型突触的比例。Kintz等[64]和VanLeeuwen等[65]研究表明,4周大强度跑台训练使MPTP小鼠皮层-纹状体通路突触前Glu释放显著降低,纹状体MSNs包含GluR2亚基的α-氨基-3-羟基-5-甲基-4-异噁唑丙酸(α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid,AMPA)受体蛋白表达、mRNA转录及其第880位丝氨酸磷酸化程度显著增高;纹状体MSNs兴奋性突触后电流的大小和幅度均显著降低,多胺敏感性内向整流丧失;陈巍等[66]研究表明,4周跑台训练可使6-OHDA诱导的PD大鼠模型纹状体Glu浓度降低,纹状体包含GluR2亚基的AMPA受体表达及MSNs膜上CaV1.3钙离子通道和相关蛋白磷酸化水平上调;刘晓莉等[67]研究发现,4周中等强度跑台训练干预可使PD大鼠模型纹状体MSNs放电频率,爆发式放电神经元的比例显著降低,持续紧张性电位的发放显著减少;纹状体MSNs对皮层刺激反应的阈强度显著增加,平均放电频率显著降低,放电频率增加的潜伏期显著延长。提示运动可能引起PD动物模型纹状体MSNs树突棘形态结构及皮层-纹状体突触连接的重塑。其机制可能是运动通过增加PD动物模型纹状体包含GluR2亚基的AMPA受体表达,降低Ca2+内流,抑制Ca2+依赖性蛋白酶的激活和胞内一系列信号级联反应的启动,最终达到降低皮层-纹状体Glu能通路的过度激活的作用。

Figure 3. The neuroprotective effect of physical exercise in PD.

图3运动在PD中的神经保护作用

Figure 4. Activation of BDNF downstream intracellular signaling pathways[59]. BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; MEK: MAPK/ERK kinase; ERK: extracellular signal-regulated kinase; GAB1: GRB-associated binder 1; Ins(1,4,5)P3: inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate; DAG: triacylglycerol; PKC: protein kinase C; Ca2+/CaM: Ca2+/calmodulin; CaMK: Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase.

图4BDNF激活下游细胞内信号通路[59]

此外,位于纹状体MSNs上的多巴胺1型受体(dopamine type 1 receptor,DA-D1R)和多巴胺2型受体(dopamine type 2 receptor,DA-D2R)是DA的主要靶点并调节生理特性和细胞信号。DA-D2R在长时程抑制(long-term depression,LTD)形成过程中起着重要的作用,其作为突触可塑性的一种形式,涉及到谷氨酸能和多巴胺能神经传递的整合,从而导致背侧纹状体运动功能的编码。在PD动物模型,通过应用DA或者DA-D2R激动剂能够导致PD运动障碍逆转[68]。陈巍等[69]采用免疫组织化学结合免疫印迹技术方法研究表明,4周中等强度跑台训练可使6-OHDA大鼠模型纹状体DA-D2R蛋白表达显著上调,运动功能改善;Lindenbach等[70]采用免疫印迹技术结合在体正电子发射计算机断层显像技术(positron emission tomography,PET)研究表明,6周大强度跑台训练可使MPTP小鼠模型背侧纹状体DA-D2R表达显著升高,运动功能改善。这些研究表明运动还能够通过增加纹状体DA-D2R的表达增强DA能信号以及抑制谷氨酸能的兴奋性来改变运动皮层和基底神经节的突触可塑性。

3 结论和展望

PD已成为全世界日益严重的问题。运动/体育锻炼可以改善轻度至中度PD患者运动功能障碍或减缓症状的发展。建议临床医生应将运动视为PD患者特别是轻度至中度PD患者的一种重要辅助或替代疗法,以降低与该疾病有关的风险(例如跌倒),改善运动功能,并延缓PD的进展。运动对PD晚期以及长期效应仍然是未知的。未来的研究需要就运动对PD晚期及长期效应进行探讨,并将在体检测运动对PD患者脑中化学物质的影响,以便能够更好地理解运动改善PD症状背后潜在的细胞和分子机制。

[参考文献]

[1] Donaldson IM. James Parkinson’s essay on the shaking palsy[J]. J R Coll Physicians Edinb, 2015, 45(1):84-86.

[2] Tysnes OB, Storstein A. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s di-sease[J]. J Neural Transm, 2017, 124(8):901-905.

[3] Yang F, Trolle Lagerros Y, Bellocco R, et al. Physical activity and risk of Parkinson’s disease in the Swedish National March Cohort[J]. Brain, 2015, 138(2):269-275.

[4] Ascherio A, Schwarzschild MA. The epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease:risk factors and prevention[J]. Lancet Neurol, 2016, 15(12):1257-1272.

[5] Lanciego JL, Luquin N, Obeso JA. Functional neuroanatomy of the basal ganglia[J]. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2012, 2(12):a009621.

[6] Zhang TM, Yu SY, Guo P, et al. Nonmotor symptoms in patients with parkinsons disease: a cross-sectional observationl study[J]. Medicine, 2016, 95(50):5400-5406.

[7] Logroscino G, Sesso HD, Paffenbarger RS Jr, et al. Phy-sical activity and risk of Parkinson’s disease: a prospective cohort study[J]. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2006, 77(12):1318-1322.

[8] Kolk NM, King LA. Effects of exercise on mobility in people with with Parkinson’s disease[J]. Mov Disord, 2013, 28(11):1587-1596.

[9] Tanner CM, Comella CL. When brawn benefits brain: physical activity and Parkinson’s disease risk[J]. Brain, 2015, 138(2):238-249 .

[10]Cheng FY, Yang YR, Chen LM, et al. Positive effects of specific exercise and novel turning-based treadmill training on turning performance in individuals with Parkinson’s di-sease: a randomized controlled trial[J]. Sci Rep, 2016,13(6):332-342.

[11]Klamroth S, Steib S, Gassner H, et al. Immediate effects of perturbation treadmill training on gait and postural control in patients with Parkinson’s disease[J]. Gait Posture, 2016, 50(6):102-108.

[12]Nadeau A, Pourcher E, Corbeil P. Effects of 24 wk of treadmill training on gait performance in Parkinson’s di-sease[J]. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2014, 46(4):645-655.

[13]Mehrholz J, Kugler J, Storch A, et al. Treadmill training for patients with Parkinson’s disease[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015, 22(8):783-790.

[14]Herman T, Giladi N, Gruendlinger L, et al. Six weeks of intensive treadmill training improves gait and quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease:a pilot study[J]. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 2007, 88(9):1154-1158.

[15]Frazzitta G, Bertotti G, Riboldazzi G, et al. Effectiveness of intensive inpatient rehabilitation treatment on disease progression in Parkinsonian patients: a randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up[J]. Neurorehabil Neural Repair, 2012, 26(2):144-150.

[16]Canning GG, Allen NE, Dean CM, et al. Home-based treadmill training for individuals with Parkinson’s di-sease: a randomized controlled pilot trial[J]. Clin Rehabil, 2012, 26(9):817-826.

[17]Rafferty MR, Prodoehl J, Robichaud JA, et al. Effects of 2 years of exercise on gait impairment in people with Parkinson disease: the PRET-PD randomized trial[J]. J Neuro Phys Ther, 2017, 41(1):21-30.

[18]Arcolin I, Pisano F, Delconte C, et al. Intensive cycle ergometer training improves gait speed and endurance in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a comparison with treadmill training[J]. Restor Neurol Neurosci, 2016, 34(1):125-138.

[19]Stuckenschneider T, Helmich I, Raabe-Oetker A, et al. Active assistive forced exercise provides long-term improvement to gait velocity and stride length in patients bilaterally affected by Parkinson’s disease[J]. Gait Posture, 2015, 42(2):485-490.

[20]Rodriguez P, Cancela JM, Ayan C, et al. Effects of aquatic physical exercise on the kinematic gait pattern gait pattern in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a pilot study[J]. Rev Neurol, 2013, 56(6):315-320.

[21]Ayán C, Cancela JM, Gutiérrez-Santiago A, et al. Effects of two different exercise programs on gait parameters in individuals with Parkinson’s disease: a pilot study[J]. Gait Posture, 2014, 39(1):648-651.

[22]Wassom DJ, Lyons KE, Pahwa R, et al. Qigong exercise may improve sleep quality and gait performance in Parkinson’s disease: a pilot study[J]. Int J Neurosci, 2015, 125(8):578-584.

[23]Allen NE, Canning CG, Sherrington C, et al. The effects of an exercise program on fall risk factors in people with Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trial[J]. Mov Disord, 2010, 25(9):1217-1225.

[24]Wong AM, Chou SW, Huang SC, et al. Does different exercise have the same effect of health promotion for the elderly?Comparison of training-specific effect of Tai Chi and swimming on motor control[J]. Arch Gerontol Geriatr, 2011, 53(2):e133-e137.

[25]Li F, Harmer P, Fitzgerald K, et al. Tai chi and postural stability in patients with Parkinson’s disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2012, 366(6):511-519.

[26]Tsang WW. Tai Chi training is effective in reducing balance impairments and falls in patients with Parkinson’s disease[J]. J Physiother, 2013,59(1):55-64.

[27]Foster ER, Golden L, Duncan RP, et al. Community-based Argentine tango dance program is associated with increased activity participation among individuals with Parkinson’s disease[J]. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 2013, 94(2): 240-249.

[28]Hackney ME, Earhart GM. Effects of dance on balance and gait in severe Parkinson disease: a case study[J]. Disabil Rehabil, 2010, 32(8):679-684.

[29]Combs SA, Diehl MD, Staples WH, et al. Boxing trai-ning for patients with Parkinson’s disease[J]. Phys Ther, 2011, 91(1):132-142.

[30]Hirsch MA, Toole T,Maitland CG, et al. The effects of balance training and high-intensity resistance training on persons with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease[J]. Arch Phys Medi Rehabil, 2003, 84(8):1109-1117.

[31]Konerth M, Childers J. Exercise: a possible adjunct the-rapy to alleviate early Parkinson’s disease[J]. JAAPA, 2013, 26(4):30-33.

[32]Wong-Yu IS, Mak MK. Multi-dimensional balance trai-ning programe improves balance and gait performance in people with Parkinson’s disease: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial with 12-month follow-up[J]. Parkinsonism Relat Disord, 2015, 21(6):615-621.

[33]Kim W, Im MJ, Park CH, et al. Remodeling of the dendritic structure of the striatal medium spiny neurons accompanies behavioral recovery in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease[J]. Neurosci Lett, 2013, 55(7):95-100.

[34]Lotharius J, Brundin P. Pathogenesis of Parkinson’s di-sease: dopamine, vesicles and α-synuclein[J]. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2002, 3(12):932-942.

[35]Hernandez-Franco P, Anandhan A, Foguth RM, et al. Oxidative stress and redox signalling in the Parkinson’s disease brain[M]∥ Franco R, Doorn JA, Rochet JC. Oxidative stress and redox signalling in Parkinson’s disease. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Royal Society Chemistry, 2013:27-60.

[36]Dexter DT, Carter CJ, Wells FR, et al. Basal lipid peroxidation in substantia nigra is increased in Parkinson’s disease[J]. J Neurochem, 1989, 52(2):381-389.

[37]Valko M, Jomova K, Rhodes CJ, et al. Redox- and non-redox-metal-induced formation of free radicals and their role in human disease[J]. Arch Toxicol, 2016, 90(1):1-37.

[38]Yoo MS, Chun HS, Son JJ, et al. Oxidative stress regulated genes in nigral dopaminergic neuronal cell: correlation with the known pathology in Parkinson’s disease[J]. Brain Res Mol Brain Res, 2003, 110(1):76-84.

[39]Dias V, Junn E, Mouradian MM. The role of oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease[J]. J Parkinsons Dis, 2013,3(4): 461-491.

[40]Zucca FA, Segura-Aguilar J, Ferrari E, et al. Interactions of iron, dopamine and neuromelanin pathways in brain aging and Parkinson’s disease[J]. Prog Neurobiol, 2017,155: 96-119.

[41] Aguiar AS Jr, Duzzioni M, Remor AP, et al. Moderate-intensity physical exercise protects against experimental 6-hydroxydopamine-induced hemiparkinsonism through Nrf2-antioxidant response element pathway[J]. Neurochem Res, 2016, 41(1-2): 64-72.

[42]Tsou YH, Shih CT, Ching CH, et al. Treadmill exercise activates Nrf2 antioxidant system to protect the nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons from MPP+toxicity[J]. Exp Neurol, 2015, 263:50-62.

[43]Nguyen T, Nioi P, Pickett CB.The Nrf2-antioxidant response element signaling pathway and its activation by oxidative stress[J]. J Biol Chem, 2009, 284(20):13291-13295.

[44]Zhang M, An C, Gao Y, et al. Emerging roles of Nrf2 and phase II antioxidant enzymes in neuroprotection[J]. Prog Neurobiol, 2013, 100:30-47.

[45]Lastres-Becker I, Ulusoy A, Innamorato NG, et al. α-Synuclein expression and Nrf2 deficiency cooperate to aggravate protein aggregation, neuronal death and inflammation in early-stage Parkinson’s disease[J]. Hum Mol Genet, 2012, 21(14): 3173-3192.

[46]Scalzo P, Kummer A, Bretas TL, et al. Serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic correlate with motor impairment in Parkinson’s disease[J]. J Neurol, 2010, 257(4):540-545.

[47]Tajiri N, Yasuhara T, Shingo T, et al. Exercise exerts neuroprotective effects on Parkinson’s disease model of rats[J]. Brain Res, 2010, 1310:200-207.

[48]Lau YS, Patki G, Das-Panja K, et al. Neuroprotective effects and mechanisms of exercise in a chronic mouse model of Parkinson’s disease with moderate neurodegene-ration[J]. Eur J Neurosci, 2011, 33(7):1264-1274.

[49]Nam JH, Leem E, Jeon MT, et al. Induction of GDNF and BDNF by hRheb(S16H) transduction of SNpc neurons: neuroprotective mechanisms of hRheb(S16H) in a model of Parkinson’s disease[J]. Mol Neurobiol, 2015,51(2): 487-499.

[50]Howells DW, Porritt MJ, Wong JY, et al. Reduced BDNF mRNA expression in the Parkinson’s disease substantia nigra[J]. Exp Neurol, 2000,166(1): 127-135.

[51]Mogi M, Togari A, Kondo T, et al. Brain-derived growth factor and nerve growth fator concentrations are decreased in the substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease[J]. Neurosci Lett, 1999,270(1):45-48.

[52]Ngema PN, Mabandla MV. Post 6-OHDA lesion exposure to stress affects neurotrophic factor expression and aggravates motor impairment[J]. Metab Brain Dis, 2017, 32(4):1061-1067.

[53]Yue P, Gao L, Wang X, et al. Intranasal administration of GDNF protects against neural apoptosis in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease through PI3K/Akt/GSK3β pathway[J]. Neurochem Res, 2017,42(5):1366-1374.

[54]Jang Y, Koo JH, Kwon I, et al. Neuroprotective effects of endurance exercise against neuroinflammation in MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease mice[J]. Brain Res, 2017, 1655:186-193.

[55]Wu SY, Wang TF, Yu L, et al. Running exercise protects the substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons against inflammation-induced degeneration via the activation of BDNF signaling pathway[J]. Brain Behav Immun, 2011, 25(1):135-146.

[56]Real CC, Ferreira AF, Chaves-Kirsten GP, et al. BDNF receptor blockade hinders the beneficial effects of exercise in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease[J]. Neuroscience, 2013, 237:118-129.

[57]Kopra J, Panhelainen A, af Bjerkén S, et al. Dampened amphetamine-stimulated behavior and altered dopamine transporter function in the absence of brain GDNF[J]. J Neurosci, 2017, 37(6):1581-1590.

[58]Berghauzen-Maciejewska K, Wardas J, Kosmowska B, et al. Alterations of BDNF and trkB mRNA expression in the 6-hydroxydopamine-induced model of preclinical stages of Parkinson’s disease: an influence of chronic pramipexole in rats[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(3): e0117698.

[59]Zhao H, Alam A, San CY, et al. Molecular mechanisms of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in neuro-protection: recent developments[J]. Brain Res, 2017, 1665:1-21.

[60]Toy WA, Petzinger GM, Leyshon BJ, et al. Treadmill exercise reverses dendritic spine loss in direct and indirect striatal medium spiny neurons in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) mouse model of Parkinson’s disease[J].Neurobiol Dis, 2014, 63:201-209.

[61]Hou L, Chen W, Liu X, et al. Exercise-induced neuroprotection of the nigrostriatal dopamine system in Parkinson’s disease[J]. Front Aging Neurosci, 2017, 9:358.

[62]Shin MS, Jeong HY, An DI, et al. Treadmill exercise facilitates synaptic plasticity on dopaminergic neurons and fibers in the mouse model with Parkinson’s disease[J]. Neurosci Lett, 2016, 621:28-33.

[63]陈 巍, 时凯旋, 刘晓莉. 运动干预通过纹状体MSNs 结构可塑性改善PD 模型大鼠行为功能[J]. 中国运动医学杂志, 2015, 34(3):228-234.

[64]Kintz N, Petzinger GM, Akopian G, et al. Exercise modifies α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor expression in striatopallidal neurons in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-lesioned mouse[J]. J Neurosci Res, 2013, 91(11):1492-1507.

[65]VanLeeuwen JE, Petzinger GM, Walsh JP, et al. Altered AMPA receptor expression with treadmill exercise in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-lesioned mouse model of basal ganglia injury[J]. J Neurosci Res, 2010, 88(3):650-668.

[66]陈 巍, 魏 翔, 刘晓莉, 等. 运动对PD模型大鼠皮层-纹状体Glu能神经传递的影响[J]. 北京体育大学学报, 2015, 38(2):61-66.

[67]刘晓莉, 时凯旋, 乔德才.运动对帕金森模型大鼠纹状体神经元电活动的影响[J]. 北京体育大学学报, 2014, 37(5):57-61.

[68]Vu.ckovi] MG, Li Q, Fisher B, et al. Exercise elevates dopamine D2 receptor in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease:invivoimaging with [18F]fallypride[J]. Mov Disord, 2010, 25(16):2777-2784.

[69]陈 巍. 运动对PD大鼠纹状体Glu能突触传递及MSNs可塑性调节机制研究[D]. 北京: 北京师范大学, 2015.

[70]Lindenbach D, Das B, Conti MM, et al. D-512, a novel dopamine D2/3receptor agonist, demonstrates greater anti-Parkinsonian efficacy than ropinirole in Parkinsonian rats[J]. Br J Pharmacol, 2017, 174(18):3058-3071.