Estimating the evolution of sea state non-Gaussianity based on a phase-resolving model*

Xingjie JIANG , Tingting ZHANG ,4,**, Dalu GAO , Daolong WANG ,4,Yongzeng YANG

1 First Institute of Oceanography, and Key Laboratory of Marine Science and Numerical Modeling, Ministry of Natural Resources,Qingdao 266061, China

2 Laboratory for Regional Oceanography and Numerical Modeling, Pilot National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology(Qingdao), Qingdao 266237, China

3 Shandong Key Laboratory of Marine Science and Numerical Modeling, Qingdao 266061, China

4 Ocean University of China, College of Oceanic and Atmospheric Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China

Abstract The occurrence of rogue waves is closely related to the non-Gaussianity of sea states, and this non-Gaussianity can be estimated using corresponding two-dimensional wave spectra. This paper presents an approach to non-Gaussianity estimation based on a phase-resolving model called the high-order spectral method (HOSM). Based on numerous HOSM simulations, a set of precalculated non-Gaussianity indicators was established that could be applied to real sea states without any calibration of spectral shapes. With a newly developed extraction approach, the indicators for given two-dimensional wave spectra could then be conveniently extracted from the precalculated dataset. The feasibility of the newly developed approach in a real wave environment is verif ied. Using the estimation approach, phase-resolved non-Gaussianity can now be illustrated throughout the evolution of sea states of interest, not just at a few specif ic times; and the level of non-Gaussianity at any time in a duration can be identif ied according to the statistics (e.g., quantities) of the phase-resolved indicators, that are obtained throughout the duration concerned.

Keyword: rogue wave; sea state non-Gaussianity; high-order spectral method; spectral geometry; wavewave nonlinearity

1 INTRODUCTION

Rogue, freak, or extreme waves are highly destructive ocean waves that represent serious threats to various marine activities, such as sea voyages,ocean f ishing, and oil exploitation. Several physical mechanisms based both on linear and on nonlinear theories have been proposed to explain the formation of such waves (Kharif and Pelinovsky, 2003; Kharif et al., 2009). Comparing to linear theories, it has been suggested that nonlinear mechanisms related to second- and third-order nonlinear wave-wave interactions (Janssen, 2003; Fedele, 2008; Fedele and Tayfun, 2009) can evidently prove the prediction of rogue wave in both aspects of occurrence probability and wave heigh magnitude.

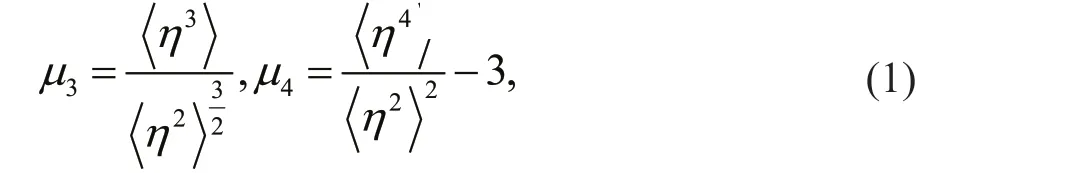

Nonlinear wave-energy focusing caused by such nonlinearities can lead to the formation of rogue waves more frequently and wave surface elevations that generally deviate from the Gaussian (normal)distribution, resulting in non-Gaussian sea states(Longuet-Higgins, 1963). Commonly used measures of the non-Gaussianity of sea state are skewnessμ3and (excess) kurtosisμ4:

whereηdenotes the wave surface elevation, and the terms in angled brackets denote statistical averages.With the consideration of nonlinearities up to thirdorder, it is clear that, skewness is contributed entirely by second-order nonlinear interactions involving bound waves (Tayfun, 1980; Tayfun and Fedele,2007; Fedele and Tayfun, 2009; Janssen, 2009), and that kurtosis includes a dynamic component (μ4free)attributable to third-order quasi-resonant interactions(Janssen, 2003; Mori and Janssen, 2006) between free waves and another bound component (μ4bound)induced by both second- and third-order bound-wave nonlinearities (Tayfun, 1980; Tayfun and Lo, 1990;Fedele, 2008; Fedele and Tayfun, 2009; Janssen,2009); these variables can be expressed as follows:

The non-Gaussianity of sea state is also sensitive to the geometries of the corresponding wave spectrum,and this relation has been well established using theoretical models (e.g., Janssen, 2003, 2009; Fedele and Tayfun, 2009) and conf irmed by laboratory and numerical experiments (e.g., Onorato et al., 2009a,b; Toff oli et al., 2009; Waseda et al., 2009; Fedele,2015). Generally, at least three geometric factors—wave steepness (hereafter, SP), bandwidth (BW), and directional spreading (DS)—can inf luence skewness,kurtosis, or both. For steeper SP and narrower BW and DS, it can be concluded that the deviation from Gaussianity will be greater, resulting in higher probability of rogue wave occurrence in such a sea state.

Following the above investigations, it has been established that two types of approach can be used to estimate skewness and kurtosis using the three spectral geometric factors. One is based on formulae/equations derived from theoretical wave models such as the Zakharov equation (Zakharov, 1968; Janssen,2003) and the Tayfun-Lo model (Tayfun and Lo,1990); and the other is based on phase-resolving models such as the high-order spectral method(HOSM) (Dommermuth and Yue, 1987; West et al., 1987) and the modif ied nonlinear Schrödinger equations (MNLS) (Dysthe, 1979; Trulsen and Dysthe, 1996).

Estimation of non-Gaussianity based on theoretical formulae and equations is highly convenient, and such estimates can certainly be applied to assess the non-Gaussianity associated with the evolution of sea state. Some methods have even been adopted in operational rogue wave forecasting systems, such as the ECMWF-IFS WAM (Janssen and Bidlot,2009; ECMWF, 2016; Janssen, 2018) and the Space-Time Extremes (STE) forecasting system included in version 5.16 of WWIII (Barbariol et al., 2015; The WAVEWATCH III Development Group, 2016; Barbariol et al., 2017). However, the indicators of skewness and kurtosis obtained using theoretical models, must f irst be obtained from theoretical models derived under the narrowband assumption in an environment with unidirectional wave propagation. When applying these indicators in scenarios with real sea conditions, specif ic parameters representing the spectral geometry are selected and undetermined parameters are introduced. Moreover, for the indicators adopted in rogue wave forecasting systems, calibrations are performed according to the f inal forecasting results;therefore, estimation of the indicators must balance the consideration of the spectral geometric factors and the other factors. Details regarding the process of calibrating operational non-Gaussianity indicators can be found in Barbariol et al. (2015, 2017) for the WWIII-STE system and in ECMWF Technical Memoranda (Janssen and Bidlot, 2009; Janssen,2018) for the ECMWF-IFS system; the latter can also be found in the Appendix of this paper.

In comparison with theoretical models, phaseresolving models can be used to assess arbitrary twodimensional (2D) spectra without any spectral shape limitations. These models adopt a given 2D spectrum as the initial wave f ield and simulate the evolution of surface elevations within a designed duration. Then,according to Eq.1, the corresponding skewness and kurtosis can be obtained based on the statistics of the surface elevations in the simulated wave f ield. The accuracy and feasibility of such models have been well verif ied by laboratory experiments (e.g., Toff oli et al., 2010). However, phase-resolving simulations are cumbersome, and performing such simulations based on wave spectrum time series obtained during sea state evolution is very time consuming. Therefore,the “phase-resolved” non-Gaussianity with the evolution of the sea state of interested can hardly be obtained and analyzed.

This paper presents a new approach that makes estimation of the phase-resolved non-Gaussianity more convenient. Using the estimation approach,phase-resolved non-Gaussianity can now be illustrated throughout the evolution of sea states of interest, not just at a few specif ic times. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The establishment of the estimation approach is introduced in Section 2. The application and validation of the approach based on certain sea states with rogue waves are described in Section 3. Finally, a discussion and the derived conclusions are presented in Sections 4 and 5, respectively.

2 ESTABLISHMENT OF THE ESTIMATION APPROACH

2.1 Experimental environment based on the HOSM

The HOSM numerical algorithm (Dommermuth and Yue, 1987; West et al., 1987) is dedicated to solve the Laplace equation for the velocity potentialφ:

In this study, the HOSM experimental environment was established based on the open-source software package HOS-ocean ver. 1.5 (Ducrozet et al.,2016), which was developed at the Laboratoire de recherche en Hydrodynamique, Énergétique et Environnement Atmosphérique of the École Centrale de Nantes (France). HOS-ocean has been extensively validated in terms of nonlinear regular wave propagation (Bonnefoy et al., 2010), and it has also been widely adopted in previous research for modeling rogue wave sea state (e.g., Ducrozet et al.,2007; Ducrozet and Gouin, 2017; Jiang et al., 2019).HOS-Ocean can ensure the stability and convergence of the calculations. For example, all aliasing errors generated in the nonlinear terms can be removed. Time integration is performed with an effi cient fourth-order Runge-Kutta Cash-Karp scheme, and the time step can be automatically selected to achieve a desired level of accuracy (or “tolerance”, with typical values in the range of 10-7-10-5; in this study, the accuracy achieved was 10-7). Moreover, a relaxation period of 10Tp(whereTpdenotes the peak wave period) is often considered (as was the case in this study) to remove numerical instabilities attributable to fully nonlinear computations that start with linear initial conditions(Dommermuth, 2000). Additional details can be found in Ducrozet et al. (2016, 2017) and Ducrozet and Gouin (2017).

The HOSM experimental environment established in this study considers a physical space of sizeLx=xlen×λpandLy=ylen×λp, wherexlen=ylen=25.5,λpis the wavelength at the peak frequency, and the discretization of the space is set asNx×Ny=256×256.The HOSM is a pseudospectral method which means certain operators including the nonlinear terms are treated in the physical space instead of the spectral space, and the transforms between the physical and spectral spaces are handled effi ciently using fast Fourier transforms. Thus, the spectral resolution of the pseudospectra can be determined as Δkx,y=2π/Lx,y, and the spectral space extends from zero tokmax=(Nx,y-1)/2×Δkx,y, wherekmaxis the cutoff frequency. Additionally, the HOSM cannot deal with wave breaking issues; therefore, a typical cutoff frequency ofkmax=5kpis generally adopted in simulations to obtain accurate solutions for the most energetic parts of the spectrum and to restrict the breaking of waves in the wave f ield to a very limited range (Ducrozet et al., 2017). For both the physical and the spectral spaces, thex-direction is taken as the principal direction of the pseudospectra,they-direction is horizontal and perpendicular to thex-direction, and thez-direction in the physical space points vertically down with a consideration of inf inite water depth.

The eff ects of spectral geometries on non-Gaussianity can be associated only with nonlinear wave-wave interactions, and therefore the HOSM simulations in this study considered only the wavewave nonlinearities and ignored other factors that might inf luence the non-Gaussianity of the simulated wave f ields, that is, wind force and energy dissipation due to breaking. According to current research, the non-Gaussianity of the sea state is mainly related to second- and third-order nonlinearities, nonlinearities up to the third order (i.e.,M=3) were considered in the simulations.

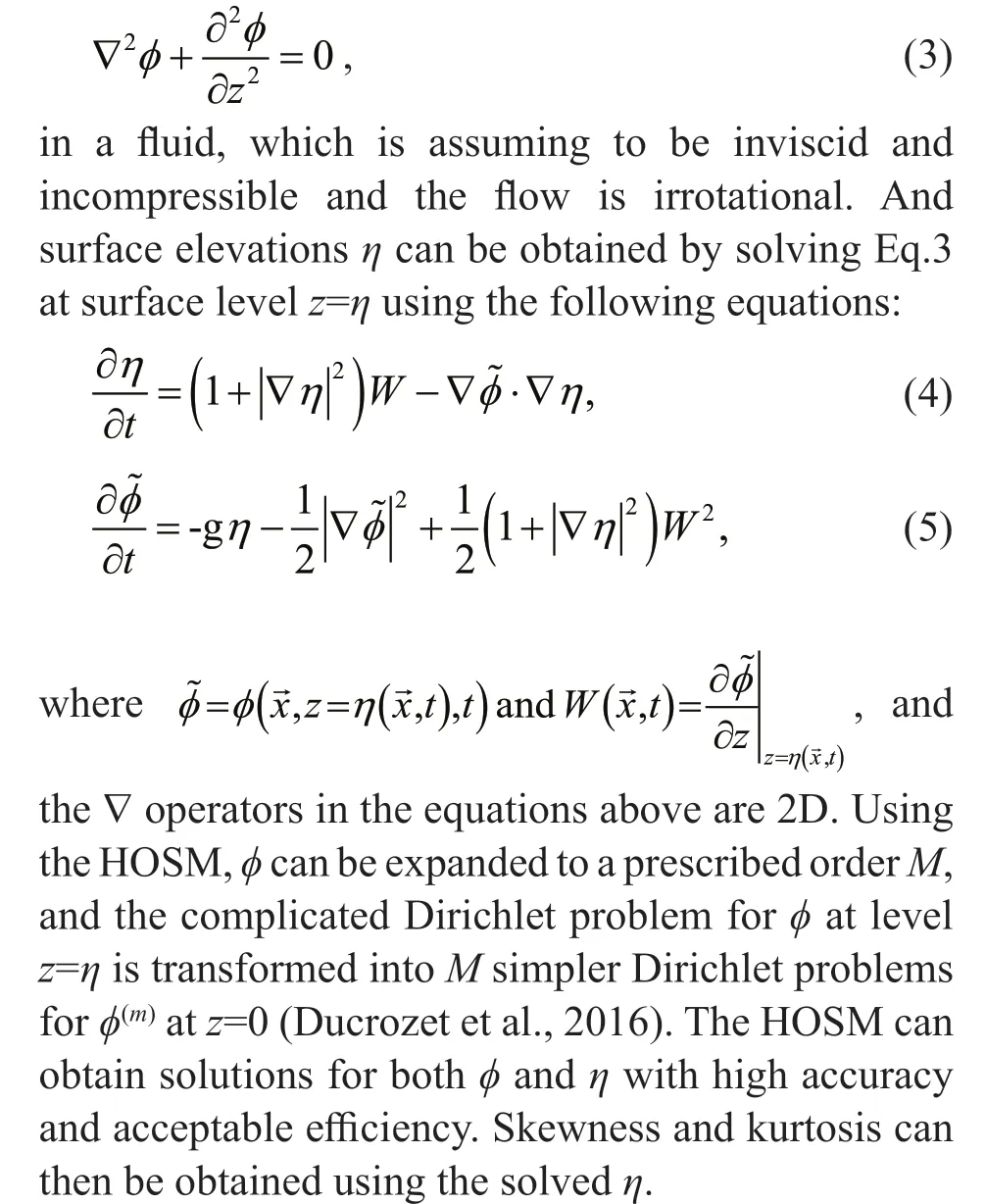

Table 1 Settings of ε and the corresponding simulated physical and pseudospectral spaces

2.2 Initial condition

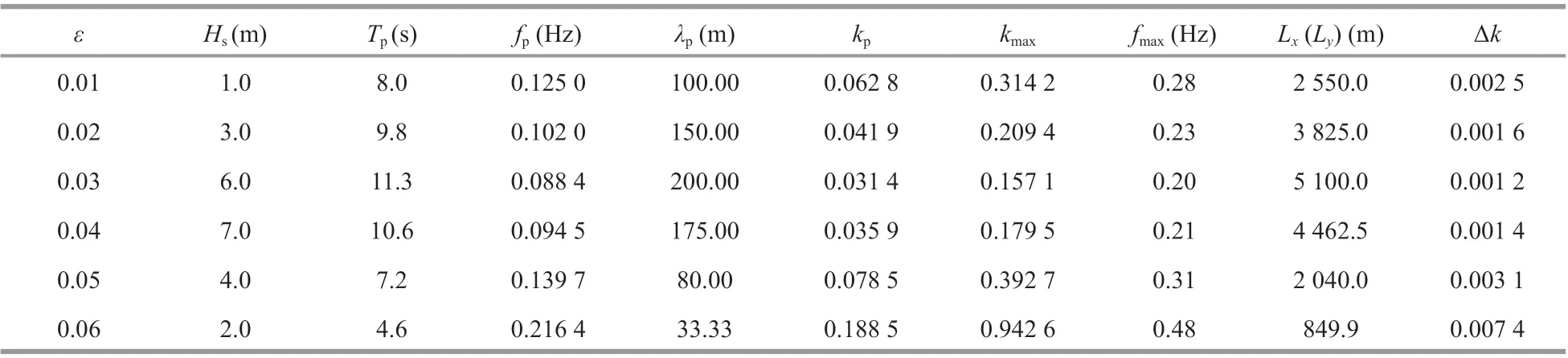

To ensure that the initial conditions of the HOSM simulations were close to those of real sea states, the Joint North Sea Wave Project (JONSWAP) spectrum and specif ic directional spreading were introduced.The JONSWAP spectrum (Hasselmann et al., 1973;Goda, 1988, 1999) can be expressed as follows:

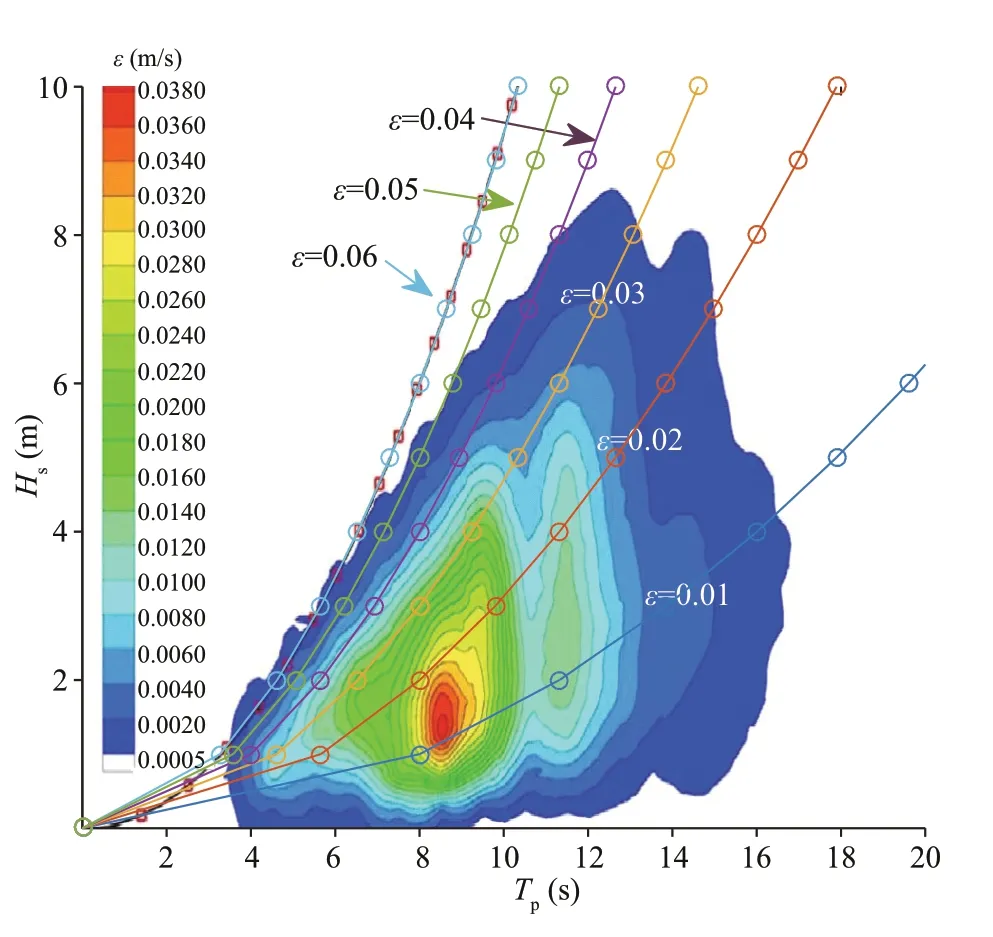

Fig.1 Combined H s- T p distribution observed in the northern North Sea from 1973 to 2001

whereHsis the signif icant wave height andλpis the wavelength at the peak frequency, which can be calculated fromfpaccording to the linear dispersion relation. Thus, SP is determined based on bothHsandfp(Tp) in Eq.6. According to observations in the northern North Sea (deep water) from 1973 to 2001 (Haver, 2002),εis generally <0.06 and most frequently in the range of 0.01-0.02 (Fig.1). To cover all observed sea conditions, the value ofεfor the initial spectra was set to vary within the range of 0.01-0.06, and considering the number of calculations involved in the simulations, the interval was set to 0.01. Furthermore, without loss of generality, each value ofεin the range was associated with a unique combination ofHsandTp. The settings of SP, together with the corresponding simulated physical and pseudospectral spaces, which are closely related toλp(Tp), are listed in Table 1.

The BW and DS values of the initial spectra can be determined fromγandΘ, respectively. For BW,parameterγwas set to vary within the range of 1.0-7.0 in accordance with the JONSWAP observations at an interval of 1.0. For DS, the range of the spreading parameterΘwas set to 8°-340°, and the interval ofΘin the range of 8°-176° (180°-340°) was set at 8° (20°).

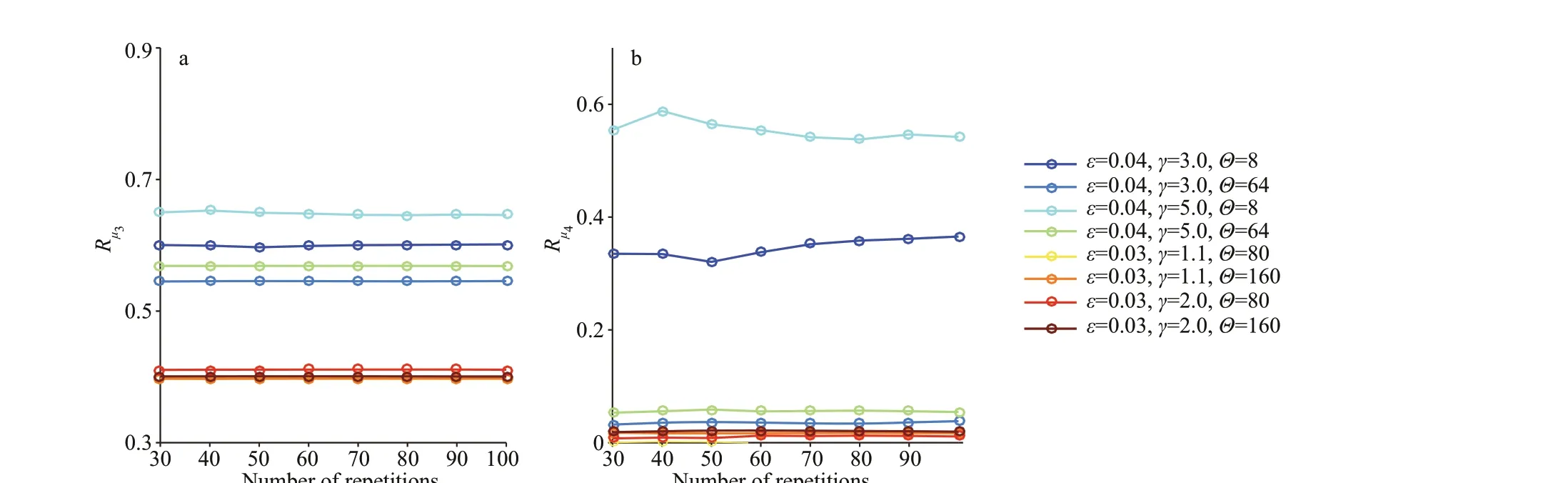

Fig.2 Results of convergence tests for the number of repetitions included in the averaging process

Finally, the total number of initial spectra with adjustableε,γ, andΘvalues was 6×7×31=1 302,and the HOSM simulations were performed for each individual case. Regardless of how the combination ofHsandTpmight vary, the number of waves involved in each initial wave f ield will always be 25.5×25.5(Section 2.1).

2.3 Skewness and kurtosis indicators

One complete HOSM simulation with a given initial spectrum is called one realization. Notably, previous experiments revealed that, with the nonlinearities that are up to third order, the most signif icant variations in skewness and kurtosis in the simulated wave f ields all occurred in the f irst 180Tpof the simulation duration,and subsequent changes in both skewness and kurtosis were minimal because the simulated wave f ield tended to be Gaussian. Thus, the simulation duration of each realization was set to 180Tp. The skewnessμ3and kurtosisμ4were calculated using Eq.1 based on the 256×256 surface elevations for each of the output simulated wave f ields, and the output interval was 1Tp. Notably, the temporal evolutions ofμ3andμ4obtained from one realization were random and unstable, and that obtaining averages of them from a number of realizations with the same initial spectrum would signif icantly reduce uncertainty, see Section 2.4.

which could be used as non-Gaussianity indicators to identify the temporal evolution of skewness and kurtosis. Thus, the non-Gaussianity of the simulated wave f ields corresponding to the initial spectra with certain combinations ofε,γ, andΘwas comparable.

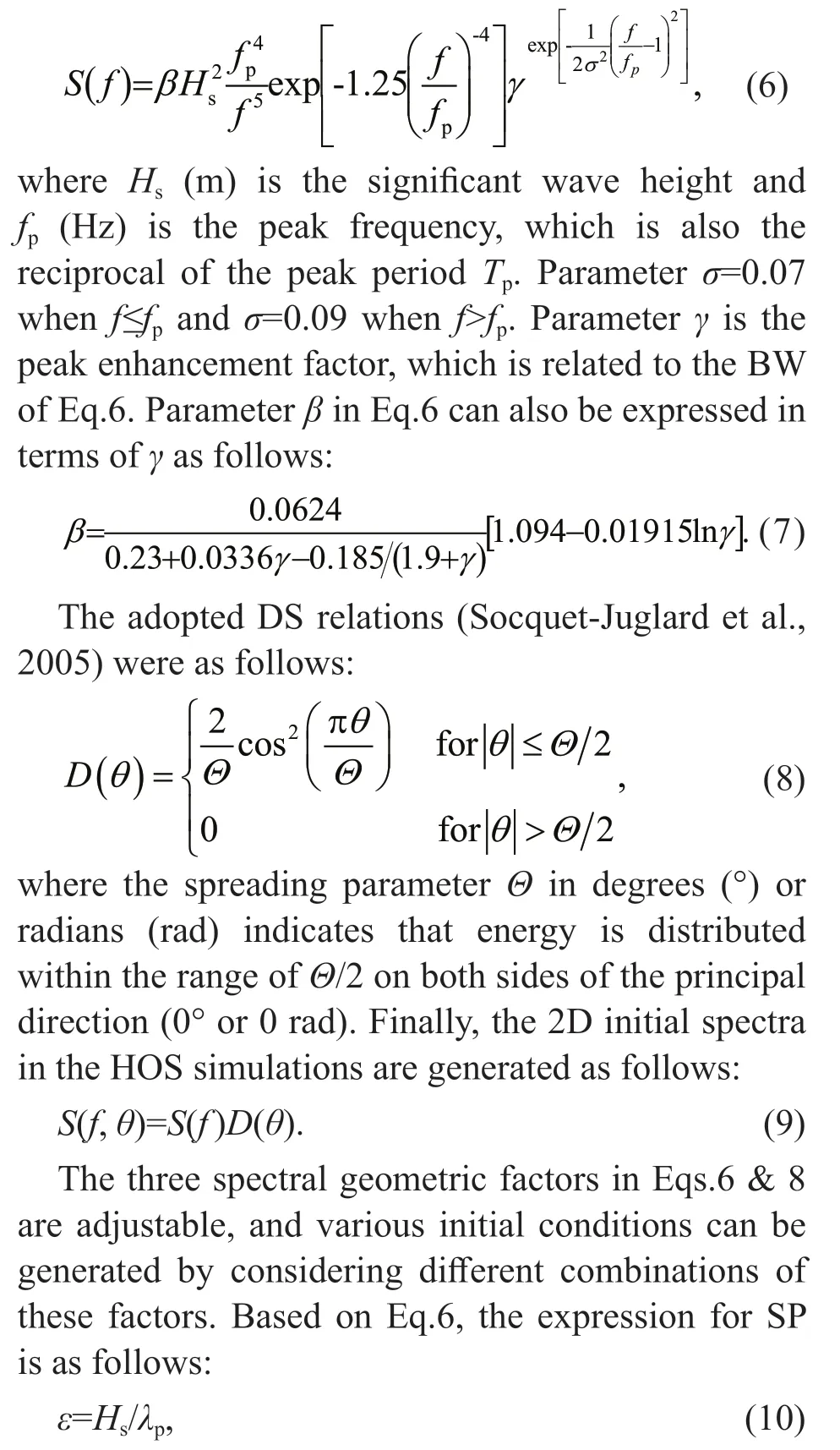

2.4 Number of repetitions

Incorporation of a large number of repetitions in an averaging process generally produces results that are stable and convergent. Therefore, eight convergence tests were performed to determine the minimum number of repetitions to be averaged. Each test involved an individual initial condition, as listed in the right part of Fig.2. For each initial condition, 100 realizations were conducted, of whichnwere then selected at random to produce a collection namedCn.Forn=30, 40, 50, ···, 100, there were eight collections to establish. The indicatorsRμ3andRμ4for each collection are shown in Fig.2.

It can be seen from Fig.2 that satisfactory convergence could be achieved for bothRμ3andRμ4after 60-70 realizations. Accordingly, the number of repetitions involved in the averaging procedure was set to 80.

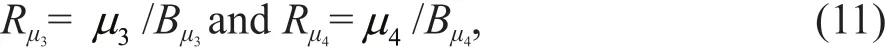

Fig.3 Parts of the non-Gaussianity references for R μ 3 with γ=3.0 (a) and ε=0.02 (b), and for R μ 4 with γ=3.0 (c) and ε=0.02 (d)

2.5 Spectral geometries and non-Gaussianity indicators

The obtained non-Gaussianity indicators constituted two reference sets for skewness and kurtosis, here denotedRμ3(ε,γ,Θ) andRμ4(ε,γ,Θ),respectively. Parts of the two references are illustrated in Fig.3. As shown in Fig.3a-d, the overall trends ofRμ3andRμ4are aff ected byε,γ, andΘ, conf irming that as the value ofεincreased, the value ofγincreased,or as the value ofΘdecreased, the value ofRμ3andRμ4increased. Moreover, the values ofRμ3andRμ4change continuously with the three geometric parameters. As illustrated in Fig.3a-b,Rμ3is aff ected most evidently by the SP parameterε; moreover,Θtends to cause slight increase inRμ3as it approaches 0°, as shown in the upper-left corner of Fig.3a. Additionally,γcan inf luenceRμ3whenΘis narrow, as shown in the upper-left corner of Fig.3b. In Fig.3c-d, within the range whereΘis extremely narrow (e.g.,Θ≤ 20°),Rμ4decreases markedly asΘwidens; whenΘis beyond the extremely narrow range, the value ofRμ4decreases, but this decrease is much slower than that whenΘwidens within the extremely narrow range.Parametersγandεcan also have certain eff ects onRμ4.For example, larger values ofγandεresult in larger values ofRμ4, and the corresponding increase becomes signif icant whenΘis extremely narrow. Same results can be found in the previous research (Gramstad and Trulsen, 2007), but in which the spectral geometries that can inf luence kurtosis were discussed in the form of spectral width in the direction of the main wave propagation (or alternatively the Benjamin-Feir Index) and in the direction perpendicular to the main wave propagation (or alternatively the crest length).

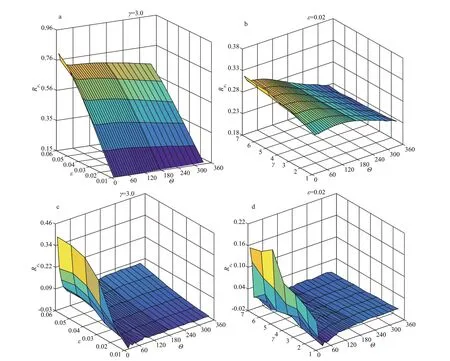

Fig.4 Polynomials f itted for σ θ( Θ) (a) and Q p( γ) (b)

It should be noted thatRμ3could be negative for some combinations of (ε,γ,Θ) owing to two possible factors. First, some of the simulated kurtosis values were rather small, and they oscillated slightly and randomly near 0, resulting in a negative average value. Second,μ4freemight be inf luenced by defocusing of wave energy as the ratio of BW to DS increases(Fedele, 2015). Therefore, negativeRμ4values represent sea states with inactive MI or the defocusing of energy, both factors might lead to decreased possibility of rogue waves forming in such sea states.

2.6 Development of the extraction approach

AsRμ3andRμ4change continuously withε,γ, andΘ, the non-Gaussianity indicators can be obtained via three-dimensional interpolation using an arbitrary combination of (εi,γi,Θi), where subscriptiindicates an arbitrary position in each of the ranges ofε,γ,andΘ, respectively. The crucial step is to determine how the parametersεi,γi, andΘithat appear in the non-Gaussianity references might be related to the geometries of SP, BW, and DS in a given spectrum.

The SP for any spectrum can be calculated as follows:

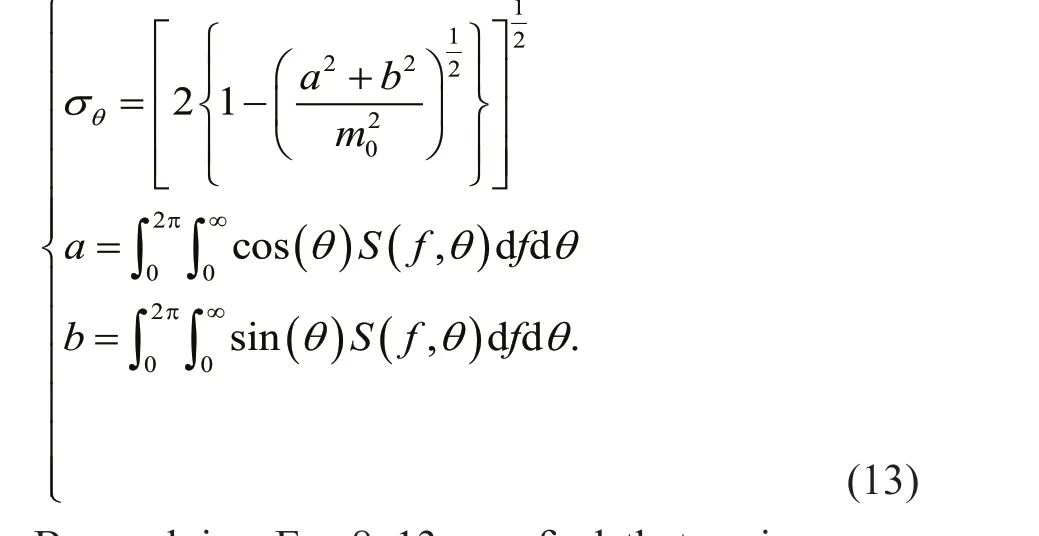

For DS, the spreading parameterσθ(Kuik et al.,1988) can be adopted as follows:

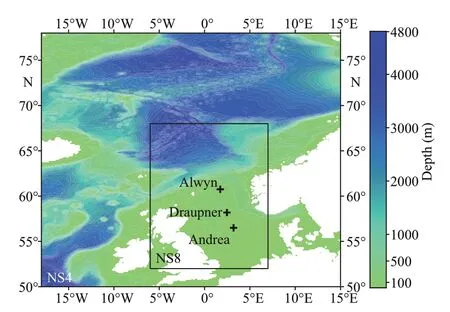

By applying Eqs.8-13, we f ind thatσθincreases monotonically withΘwithin the range ofΘ∈[8°, 340°], as indicated by the black solid line in Fig.4a. This line can be f itted by a second-order polynomial, shown as the red dashed line in Fig.4a,and expressed as follows:

Thus, parameterγican be obtained by solving for the root of Eq.16 in the range of (γ∈[1, 7]) withQpcalculated from the given spectrum.

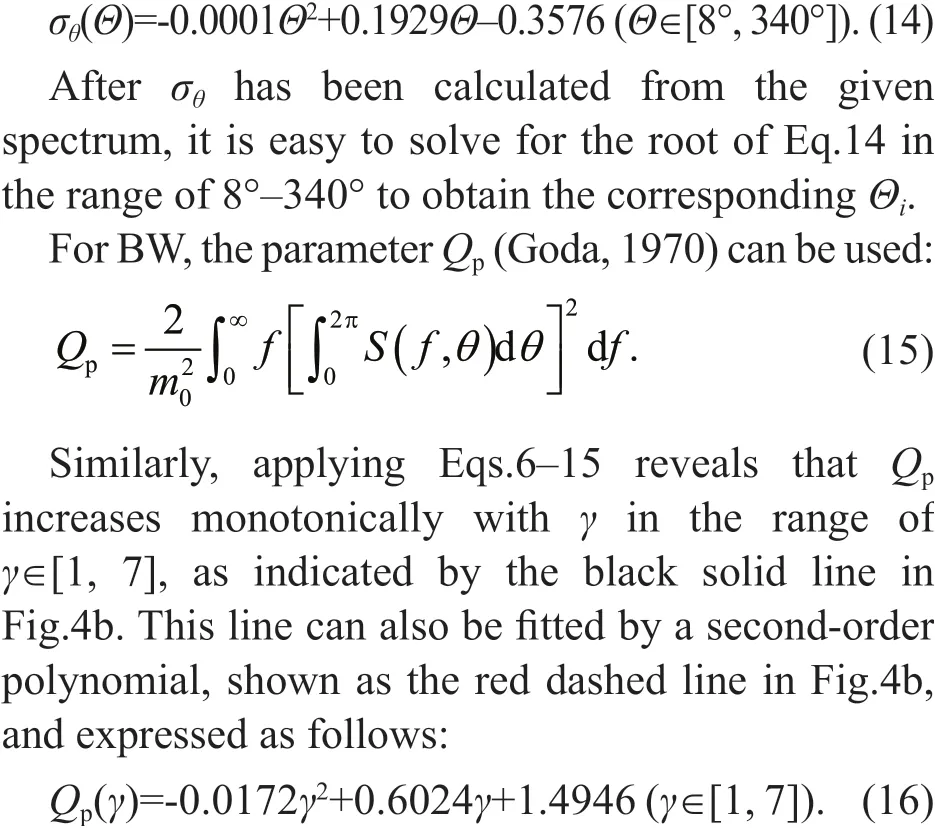

Table 2 Basic information regarding the studied rogue wave events

3 APPLICATION AND VALIDATION OF THE ESTIMATION APPROACH

3.1 Rogue wave events and wave modeling

The newly established approach is applied to some sea states with occurrence of rogue waves. The 10 rogue wave events discussed in this section were all observed using laser sensors installed on oil platforms in the North Sea. The locations of the platforms and UTC times at which the events occurred are listed in Table 2, together with the synchronously observed maximum wave heights (Hmax) and signif icant wave heights (Hs), which were digitized from Magnusson and Donelan (2013) for Draupner and Andrea and from Guedes Soares et al. (2003) for the Alwyn events.

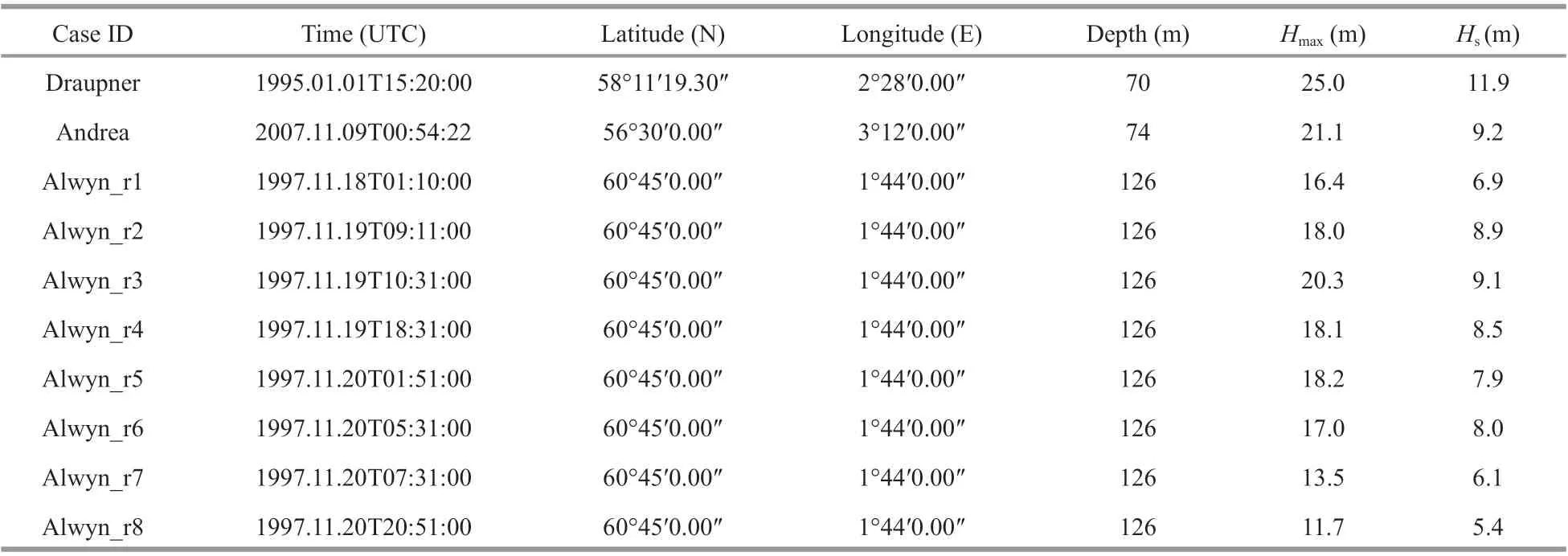

In this study, the wave f ields containing the selected events were reproduced using the WWIII wave model ver.5.16 (The WAVEWATCH III Development Group,2016). The modeled spectral space was set with 36 directions at intervals of 10° and 35 frequencies spaced from 0.042 to 1.05 Hz as a geometric progression with a ratio of 1.1. The computational grids of the physical area modeled, as illustrated in Fig.5, include an outer grid named NS4 (50°N-78°N,-18°E-15°E) with 0.25°×0.25° resolution and an inner grid named NS8 (52°N-68°N, -6°E-7°E) with 0.125°×0.125° resolution. Bathymetric data were obtained from ETOPO1 of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Geophysical Data Center (NGDC) (National Centers for Environmental Information, 2017), and the wind force adopted in the simulations were derived from ECMWF-ERA5 reanalysis hourly data (Copernicus,2018). As indicated by the Case IDs listed in Table 2,the modeling started 30 days before and ended 1 day after the occurrence of the Draupner and Andrea events, while for the Alwyn events, the modeling commenced 30 days before Alwyn_r1 and concluded 1 day after Alwyn_r8.

Fig.5 Computational grids of the North Sea

Some of the simulated bulk wave parameters are illustrated in Fig.6a-d together with observed data digitized from published research for comparison.Comparison of the black solid lines denoting the digitized observations with the blue lines of the simulations reveals acceptable reproduction of the observed sea states; thus, these data provide a reliable foundation for the following analyses. The simulated signif icant wave heightHs, peak wave periodTp, peak wavenumberkp, peak wavelengthLp, and parameterkpd(kp×d, wheredis the water depth at the sites;Table 2) at the times of occurrence of all the rogue wave events are listed in Table 3.

3.2 Validation of the estimation approach

Fig.6 Comparison of simulated results and observations for the Draupner (a), Andrea (b), and Alwyn (c)-(d) events

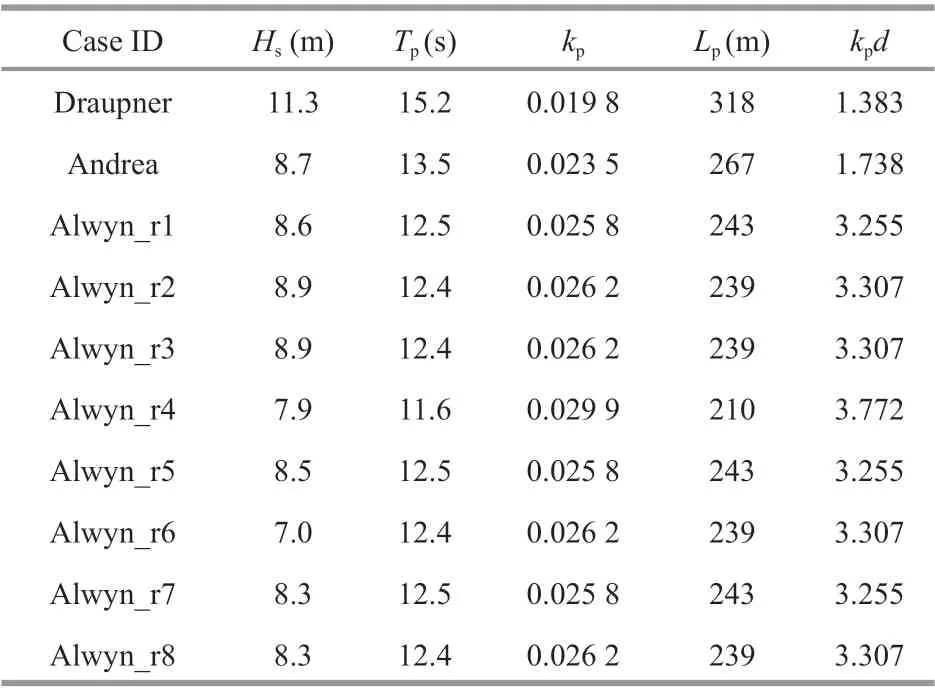

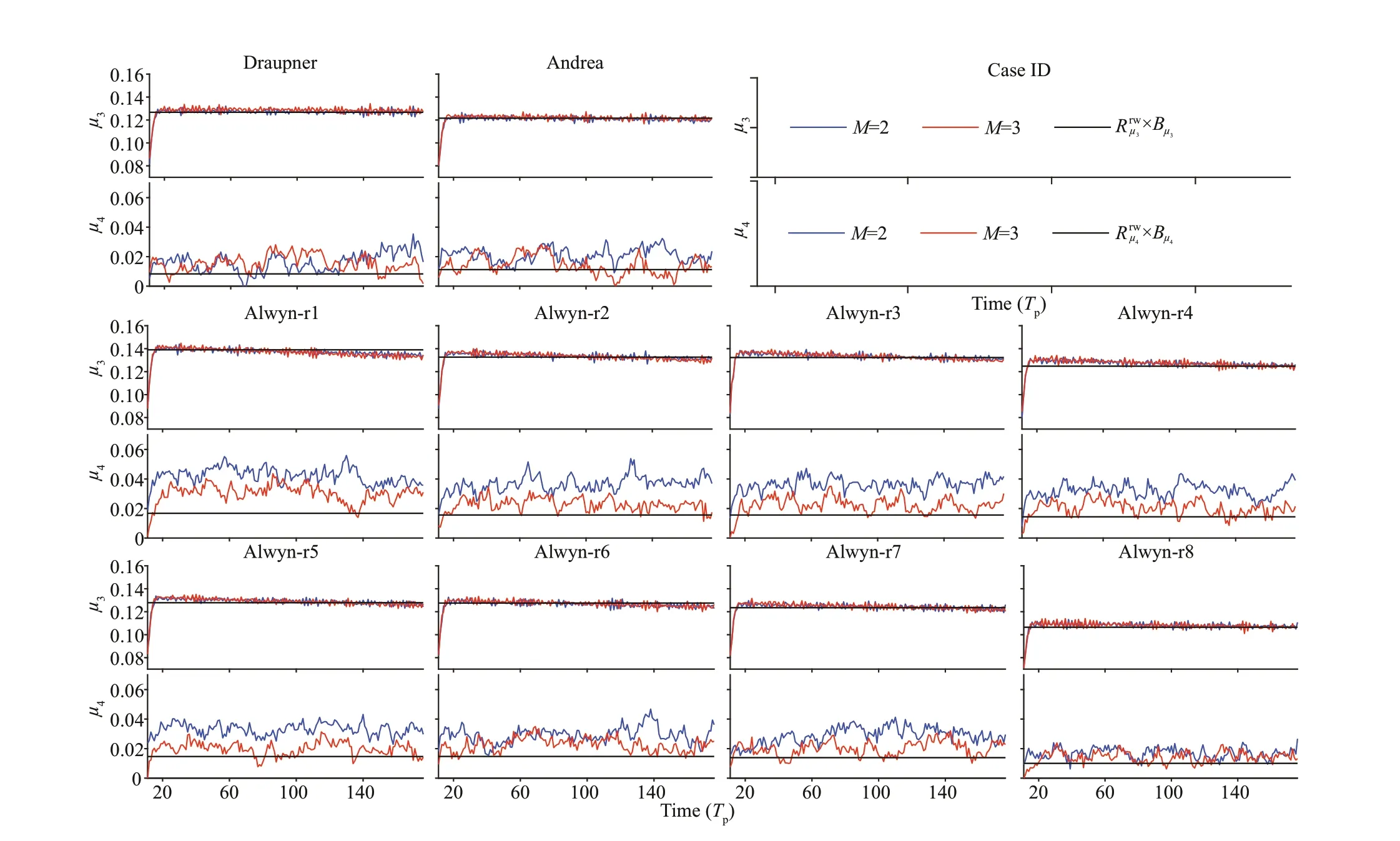

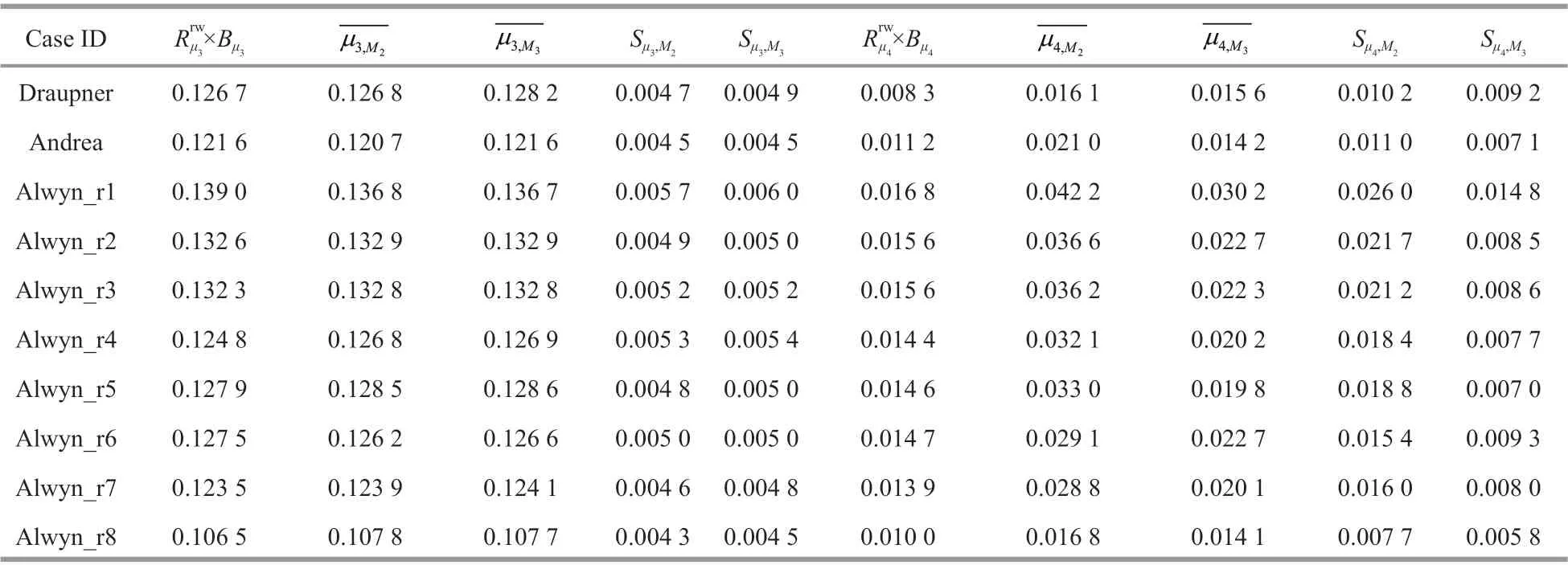

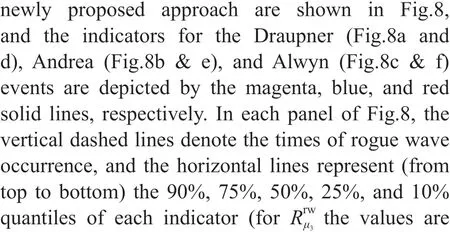

To validate the estimation approach, additional HOSM simulations were performed based on the same experimental environment as that established in Section 2.1. However, the initial conditions were replaced with modeled wave spectra for the 10 events, and simulations that considered the secondorder nonlinearities (M=2) only and both the secondand third-order nonlinearities (M=3) were performed separately to elucidate the dominant mode in the wave f ields. A similar approach was used in previous research (Fedele et al., 2016) in which the Draupner and Andrea events were studied.

Table 3 Simulated wave parameters at the times of rogue wave occurrence

3.3 Evolution of non-Gaussianity in rogue wave sea states

Fig.7 Results of the additional HOSM simulations

Table 4 Parameters obtained in the validation

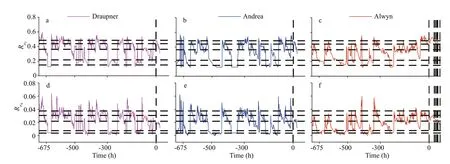

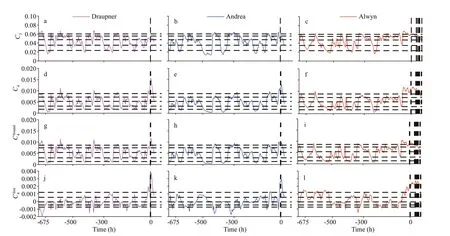

Fig.8 Non-Gaussianity indicator variations during the rogue wave events

4 DISCUSSION

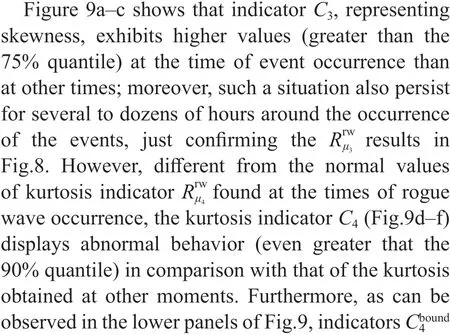

To assess the diff erences in non-Gaussianity indicators estimated using theoretical formulas and the newly proposed approach, several operational indicators adopted in the extreme wave forecasting system of the Integrated Forecasting System operated by European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF-IFS) are adopted here as anexample. The meaning of each indicator and the methods used for calculating them are given in the Appendix. The evolution trends of the operational indicators are illustrated in Fig.9, where the colored,horizontal, and vertical lines depict the same events,quantiles, and times just the same as Fig.8.

Table 5 Non-Gaussian indicators at the times of rogue wave occurrence

Fig.9 Non-Gaussianity indicators obtained by the operational rogue wave forecasting system (ECMWF-IFS)

As expressed in Eqs.2 & A2 (from Appendix),kurtosis comprises both a dynamic (free) part and a bound part. The dynamic contribution is relatively small; for example, it can be <10% of the bound component in a normal sea state with broad BW and DS (Annenkov and Shrira, 2014); however, it can reach high levels in specif ic wave environments,suggesting that MI are active (Janssen, 2003; Fedele,2015). TheC4freeat the occurrences of the events are found being>20% of theC4bound, which is slightly larger than a “normal” value expected. However, the lack of notable discrepancies between the black (M=2)and red (M=3) lines in the lower part of each panel of Fig.7 indicates that the kurtosis of the selected rogue wave sea states is dominated by second-order nonlinearities, thus, the third-order nonlinearities and the associated MI are inactive; similar conclusions can also be found in Fedele et al. (2016). As mentioned previously, the operational indicators derived from the theoretical formulae might not be suitable for real sea states, thus, the prominentC4values found at the times of rogue wave occurrences might be caused by an improper calibration. It should be noted that the estimation results obtained with the phase-resolving model, including theRμ3andRμ4values obtained in this study, might also be incomplete. It is diffi cult to discuss which kind of estimation is correct or not with the current results, and that is not the main purpose of this study.

The non-Gaussianity indicators obtained in diff erent ways can provide diff erent perspectives for studying rogue wave sea states. And it is not the f irst time that a phase-resolving model, such as HOSM,has been applied to assess rogue sea states (e.g.,Trulsen et al., 2015; Fedele et al., 2016; Jiang et al.,2019). However, phase-resolving simulations can be performed only using several spectra selected from the full spectral evolution of the sea state because full simulations can be cumbersome. In this study,using the precalculated dataset and the extraction approach, phase-resolved non-Gaussianity indicators can be obtained conveniently. Thus, the “normal” or“abnormal” behaviors of sea state non-Gaussianity can be identif ied according to the statistics of the phaseresolved indicators, which are derived throughout the simulated sea states. Therefore, this study provides a new perspective for studying non-Gaussian sea states and the associated rogue wave sea states, and such studies can be performed based on the phase-resolved non-Gaussianity throughout the evolution of sea states of interest, not just at a few specif ic times.

With respect to real ocean conditions, our model is certainly an oversimplif ication; for example, it focuses purely on the nonlinearities among waves,ignoring other physical mechanisms that might inf luence non-Gaussianity, e.g., wind forcing, wave breaking. Furthermore, the interaction between two wave systems were also ignored, regarding that for two systems do not interact much, the combined wave system appears to be more Gaussian than the corresponding partitioned wave systems (Støle-Hentschel et al., 2020). Therefore, the model was established based only on unimodal spectral shapes and bimodal shapes were ignored. And in the application, the quantiles are just obtained based on samples simulated in a few months, involving more samples might provide more suitable criterion.Further improvement of the new estimation approach can be done in future studies.

5 CONCLUSION

In this study, we established a systematic approach for estimating the evolution of sea state non-Gaussianity. The newly established approach includes:i) a set of precalculated indicators representing the relation between sea state non-Gaussianity and various combinations of the SP, BW, and DS geometries, and ii) an approach that can extract the skewness and kurtosis indicators from the precalculated dataset for given 2D spectra. Because the precalculated dataset was obtained based on HOSM (phase-resolving)simulations, the indicators can be applied to real sea states without calibration of spectral shapes. With the newly developed extraction approach, estimating the phase-resolved non-Gaussianity of a given sea state becomes convenient, and the phase-resolved non-Gaussianity can be estimated with the evolution of sea state. Validation of the estimation approach was performed based on analysis of sea states in which real rogue waves occurred. The sea states were reproduced using the spectral wave model WWIII,and additional HOSM simulations were conducted with simulated wave spectra at the time of occurrence of the rogue wave events. The acceptable goodness of f it of the extracted indicators to the simulated results verif ied the feasibility of the estimation approach for use in real wave environments.

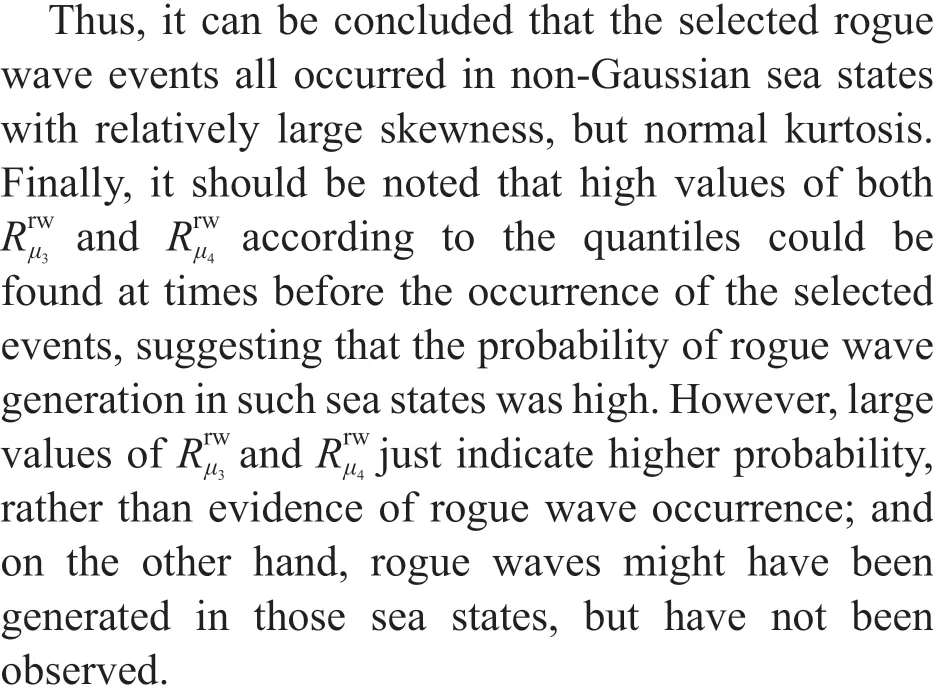

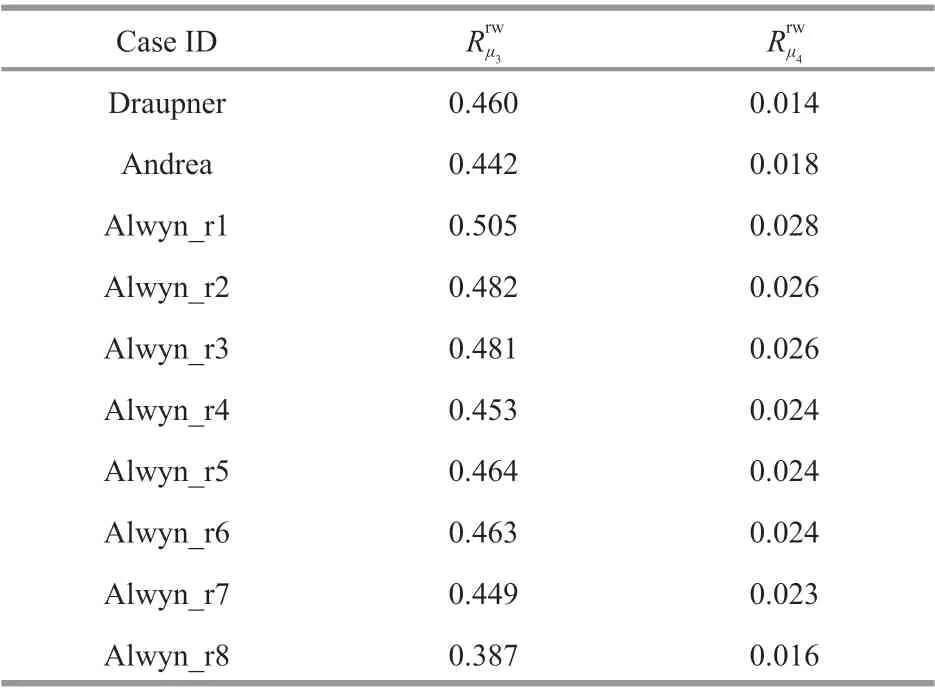

With the estimation approach, the evolution of the phase-resolved non-Gaussianity in the selected sea states was illustrated. It is found that the selected rogue wave events all occurred in non-Gaussian sea states with relatively large skewness, but normal kurtosis; and that large values of both the skewness and kurtosis indicators can be found at times before the occurrence of the selected events, suggesting high probability of rogue wave generation in such sea states.And it should be noted that the “large” and “normal”judgements given above are based on the statistics of the phase-resolved non-Gaussiniaty indicators,which are obtained throughout the evolution of the simulated sea state.

In comparison with the evolution trends of certain operational indicators derived from theoretical formulae, diff erent behaviors of non-Gaussianity of the same selected the sea states are found. Although,the results of the newly proposed approach seem more reasonable, it is diffi cult to discuss which kind of estimation is better; and the newly proposed approach still has defects. However, this study provides a new perspective for studying the non-Gaussian rogue wave sea states, and further research could be performed on this basis.

6 DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the f indings of this study are available on request from the f irst author Xingjie JIANG (jiangxj@f io.org.cn) or the corresponding author Tingting ZHANG (zhangtt@f io.org.cn).

7 ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Guillaume Ducrozet and Yves Perignon from the Research Laboratory in Hydrodynamics,Energetics and Atmospheric Environment (LHEEA)of the École Centrale de Nantes and The French National Centre for Scientif ic Research (CNRS) for their assistance in helping us understand the HOSM method and the use of HOS-ocean.

Journal of Oceanology and Limnology2022年5期

Journal of Oceanology and Limnology2022年5期

- Journal of Oceanology and Limnology的其它文章

- Comparison of three f locculants for heavy cyanobacterial bloom mitigation and subsequent environmental impact*

- Eff ect of light intensity on bound EPS characteristics of two Microcystis morphospecies: the role of bEPS in the proliferation of Microcystis*

- Community structure of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in algae- and macrophyte-dominated areas in Taihu Lake, China*

- Tidal water exchanges can shape the phytoplankton community structure and reduce the risk of harmful cyanobacterial blooms in a semi-closed lake*

- Eff ect of random phase error and baseline roll angle error on eddy identif ication by interferometric imaging altimeter*

- Sodium acetate can promote the growth and astaxanthin accumulation in the unicellular green alga Haematococcus pluvialis as revealed by a proteomics approach*