建筑与交互*

徐卫国,唐克扬,菲利普·比斯利,迈克尔·福克斯,亨利·埃克斯,鲁伊里·格林,李 力,刘 洁

1 机器人场所及其互动I 徐卫国

我们的生活已经习惯于“人、建筑、环境”三者共处的场所,但事实上,已经有第四者开始来到我们习以为常的场所,它就是机器人。各种机器人已经出现在我们的身边,工业机器人除了可以代替工人进行装配、打磨、焊接、包装等复杂重复的工作外,还应用在汽车制造、金属成型、塑料工业、电子电气、化工行业等;许多地方已经出现直接服务于生活的各类机器人,安全类智能服务机器人如安保机器人、巡逻机器人[1];健康类智能服务机器人如用于智慧养老地产项目的有陪伴娱乐、健康检测、健康顾问、紧急报警机器人[2];运输类智能服务机器人如移动式搬运机器人、社区外部及室内配送的机器人、餐厅送餐机器人[3];娱乐类智能服务机器人如舞蹈机器人、足球机器人;管理类智能服务机器人如物业管理机器人、管家型机器人等等。这样,我们正在面对“机器人、人、建筑、环境”这个新的四位一体的场所。在这一新系统中,建筑—机器人—人—环境如何持续进行积极的互动,以维护人类聚居空间的合理性、舒适性及宜居性,这也成为建筑学科需要研究的新的基础理论问题。

互动建筑或称“建筑的互动”是基于传统的场所理论提出的,场所由建筑、人、及环境三者组成[4],这三者之间的积极互动才能营造宜居的建筑场所;但是,当我们分别考察这三要素时发现,人在活动及参与事件过程中表现出的行为无疑是动态的,建筑环境随着自然因素如日月星辰、风霜雪雨、季节更替的变化而不断地变化;可建筑一旦建成,就再也不会有丰富的动态表现,只能非常有限的部件可动如门窗;那么,如何能让建筑(设计建造的结果)随着人、环境的变化而变化,以便真正实现建筑—人—及环境三者之间的积极互动呢,互动建筑的发展正是为了解决这一问题[5]。另一方面,可持续发展已经是人类共识,绿色建筑、生态建筑、建筑节能等等是建筑发展的必由之路,但是如何真正实现建筑的有效生态化,需要以建筑为载体和基本单位、将各种已有技术综合到一起、创造一个新的建筑系统来完成这一使命,基于互动系统的互动建筑是一种潜在的有效途径[6,7]。这一新的建筑系统涉及到建筑、结构、水暖电、声光热,涉及到健康室内、建材循环、能源系统等等,通过互动建筑的互动综合系统可以统合各个专业完成这一使命。

事实上,我们还没有来得及对传统场所内的建筑互动问题进行深入研究,就已经遇到了新的问题,那就是“机器人—人—建筑—环境”四位一体的机器人场所的互动问题,机器人场所的宜居性建立在机器人—人—建筑—环境四者之间积极互动的基础上,这种积极互动包含了6种互动关系,其中3 种为我们前所未遇的新的互动关系,即机器人与人、机器人与建筑、机器人与环境的互动关系;另外3 种是对传统场所中互动关系的更新,即人与智能建筑、人与新的环境、智能建筑与新的环境的互动。机器人可以给人带来新的场所感觉,帮助场所形成新的特性、使人对环境产生新的认知;机器人可以作为建筑空间的调和者,帮助建筑空间增加活力、并增加人际交流的可能性。

上述机器人场所关系中之所以用了“智能建筑”,这是因为在机器人时代,传统的建筑在智能技术及设备的武装下也逐渐智能化,一方面,它初心不改持续实现传统场所赋予它的发展使命、与“人—环境”积极互动;另一方面,在装载各种智能系统的同时,它自身也越来越像一个建筑机器人了。建筑作为居住的机器人,随着智能技术的不断发展,它将以信息感知为基础、以行为适应为规则、以沟通交流为保证。建筑将由可变的结构、可变的部件、可变的空间等组成,这些可变零件将由一个控制系统进行自动控制,该系统包括了传感系统、中枢系统、以及机械系统。传感系统利用传感器对外在环境信息进行收集;中央处理系统通过相应的程序对收集到的信息进行分析整合,再通过需求程序产生新的信息指令进行传递;动力及机械系统接受中央处理系统的指令,推动建筑的结构或构件进行运动[8],建筑可展现其最佳形态,满足场所中其它各个存在者的要求,与它们和谐共处,以使场所处于最好的宜居状态。这样建筑也成为真正的智能建筑。

如此来看,对于建筑的互动问题我们不能仅仅着眼于传统场所中建筑进行研究,不应仅仅满足于现有技术的使用,而是应该敏锐地看到影响人类聚居的传统建筑学理论基础发生了变化,即机器人及智能建筑作为有智能水平的角色打破了人类生活场所的平衡,急需对聚居场所理论进行重新思考及完善,才能保证新的聚居场所的建设及运维有理可依,从而正常运转;因此应该针对机器人场所的建筑进行理论架构及实施研发,也就是应该进行建筑机器人的场所理论研究,同时进行该场所内各个存在者之间积极互动条件的创造,以保证我们人类的生活越来越高质量的进行。机器人时代正在向我们走来,机器人及智能建筑将深度介入我们的社会和生活,它将重新定义建筑及社区,也正在重新定义互动建筑或“建筑的互动”。

2 运动的建筑:空间“交互”的前提和方法论I 唐克扬

建筑的关键词之一是永固性(permanence),大多数人认知的建筑是不可“变”的,但让建筑活动起来并非当代才有的梦想。《隋书》便提到,大兴长安城的规划者宇文恺曾为隋炀帝建造一座“观风行殿”,“上容侍卫者数百人,离合为之,下施轮轴,推移倏忽,有若神功。[1]” 跨入现代,富勒(Buckminster Fuller)等人天才地提出将工业文明最重要的发明汽车和住宅结合在一起,空间从此可变[2]。和以往游牧民族的帐篷仅仅强调“可移动”不大一样,我们时代的“活动建筑”,是将农耕时代静态空间文化特有的“居者有其屋”观念,和全球化中涌现的“移动性”(mobility)无缝嫁接,正如房车使用的都是工业标准的运输渠道和驳接装置,而它的内饰却大多向传统家居看齐[3],仅仅考虑这样的设计的建筑学特征,你并不会意识到自己是在路上,还是置身于游艇、飞机类似的空间中1)可以比拟的例子是20 世纪初的纽约剧院广泛使用复杂机械装置构成的活动舞台,表达时间和空间的运动,现象和实质没有可见的联系。或者,结构和感受也可以没有联系,像把传统住宅放置到摩天大楼的骨架中构成一个超大尺度的“集合住宅”。参见雷姆·库哈斯,《癫狂的纽约》,三联书店,2013 年。。

从这个角度,我们领略到,某些表面上不可以移动的建筑其实也和“活动建筑”有关,比如火车站。火车站最核心的功能令得它的设计原则不大可能再依循古典惯例,不再是容器,而是一个运动的起点。更有甚者,它还需要扮演“控制器”的角色,除了等候空间,大火车站往往还连带着它的货场、轨道、站台和调度设施,主空间通过蛛网般的网络和它们连接,这些貌似只是配套的设备空间才是“活动建筑”真正的主角[4,5]。

由此提出了一个重要的理论问题,它势必成为“人屋交互”的基础:如果假定建筑有可能成为某种响应使用者的智慧体,那么交互并不一定局限于物理运动层面的交互,空间的“活动”其实和“运动”是不一样的。或者,这种运动有可能是不那么引人注目的“微运动”(micro-movement)。桑内特(Richard Sennett)提到,当代的运动身体其实是一种被宁息(pacified)了的身体,就像一个开车的人一样,我们的身体要么并不移动,要么只是消极地、按照一定规律机械运动着——眼睛微微眨/转动注视各个信息界面(前挡风玻璃,仪表盘和导航装置,后视镜等),双手小幅度转动驾驶方向盘,脚尖轻踩油门和刹车,但是与此同时,这却引起了汽车的显著和快速的运动,以上,和传统驭手全身投入驾驶马车的那种模式有着天壤之别[6]。

这种“微运动”却可以大大改变建筑之观感和品性。不是整体移动房屋的一部分,普莱斯(Cedric Price)的“欢乐宫”(Fun Palace)改变的主要是空间的结构,房屋作为一个整体自身没有显著的位移和形变,但构成房屋的某些部件发生了质的变化,不必表现为显见的运动,甚至不甚可见——比如只是相对关系的改变(结构),空间品质(温湿度,声环境)的提升,等等[7]。2021 年获得普利兹克建筑奖的法国建筑师拉卡通和瓦萨尔(Lacaton&Vassal)的建筑理念,正是基于以上认识针对日常空间进行调适性设计,比如一座大建筑可以根据需求临时区分、组装为新的用途,推拉门关合之后,有人使用的小空间获得上佳的舒适度,而建筑整体取得更出色的能耗表现。

在这个意义上笔者进行了一系列的设计教学,与其说它们是时下常见的“人屋交互”操作不如说是为这一课题提供了基础思维的训练。两种作业类型,一种基于房屋本身要素的拆解、位移和重组;另外一种,空间自身可能未必显形,只要有一个开放式的语境——可能是建筑、景观和整个城市,使用者遵循着特定的指令和运动路径,就可以产生一个有复杂互动的空间,而且依理可以“层出不穷”。这样做的好处是把单点式的和线性思维方式所导致的互动变成了更加系统的人和建成环境的关系,或者导致更具意义的建成环境[8]。

对于初学者而言,我们不能仅仅为了一种截然(arbitrary)的实用范式展开研究,也无法仅仅是为了凸显特定技术的价值就为它指派一种空间具形,这样才会有真正的创新。比如,为了方便储存和取用图书会使用紧缩书架(compact shelf),人踏入书架之间就会重新定义这个书架的结构,但是这种模式对采用机器人取书的全自动书库无效;与此同时,如果要服务更多人的通识阅读,我们便无法厚此薄彼,仍需回到图书馆传统的开架模式,而且,对于“通识”的任何诠释,图书馆建筑母体的设计思想,都会对书架涉及的互动技术施加不可忽略的影响。无论如何,以上我们将意识到空间“具体”(actualized)的内容和“本地”的形式对交互设计产生重大的意义。正如我们在著名的法国国家图书馆竞赛中所看到的那样:图书馆是一类典型的信息空间,信息将整体存在,并和多名用户产生系统的关系;图书馆的空间形式又和不同时代对于学习、阅读的定义有关。库哈斯在上述竞赛中提出的方案,是用九部电梯穿透建筑形体产生暂定的公共空间,这种关系“是机械的而不是建筑学的”,建筑的各要素之间灵活的新关系,释放了原有的各种假设同时也造成新的意义问题[9]。

由此可见,空间交互的基本机制不止于我们平时所谈到的视觉层面,进而言之,空间领域的输入和输出也远没有“动作(身体运动)到抽象指令到动作(空间本身的物理运动)”那般简单[10]。按照交互领域学者的研究,实体性的用户界面至少分为自驱动(actuated)的,非刚性(non-Rigid)的和模块化(modular)的,翻译成和我们的主题相关的话题:1)建筑可以有区别于整体的个体,每一部分都可以独立地接受输入并产生反馈;2)建筑的形式,主要是它整体的空间类型(type),具有和简单的外貌(颜色,图形)一样重要的意义,比如一座环形的长廊,会在用户和建筑之间产生与和一座直线的长廊完全不同的互动关系;如果说前两者并不仅仅是建筑独有,同样存在整体局部关系的(类)平面媒介,具有类型属性的活动雕塑等,都可能具有“自驱动”的属性,很多空间造型亦具备“非刚性”的特点,那么“模块化”确实是建筑师更熟悉的设计思想,类似、可复制且按复杂方式组装的个体形式,协同后产生个体关系的变化,可以成为模块化实物用户界面(Modular Tangible User Interface)的一个起点[11]。

实体性的用户界面主要是作为整体而发生交互意义,不像图形界面(GUI)那样可能仅仅是局部起作用[12]。更有甚者,真正的空间交互不大可能是一种独立的技术,因为和具体的用途有关,它大多以设计的形式存在——那就意味着空间交互会有确定的语境,这恰恰是建筑实践的基本特点。

3 互动性的宣言:反对柏拉图式建筑 I 菲利普·比斯利 I 胡寒阳 译

柏拉图(Plato)在他的《蒂迈欧篇》(Timaeus)中,用一个完美的球体描述宇宙的根源。“灵魂,从中心向边缘漫延,充斥所有空间,也包裹了自己。她自我转动,成为永恒、理性生命的神圣开端。”

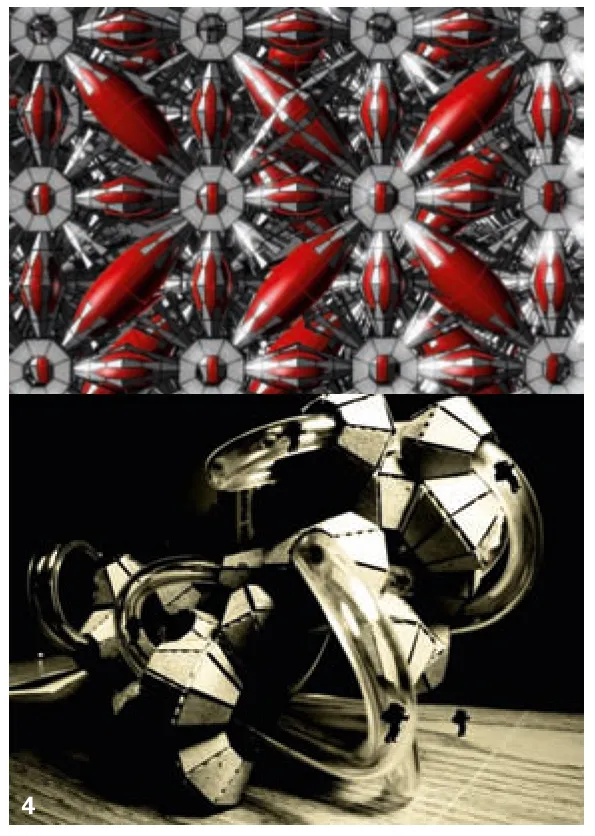

传统建筑设计常以柏拉图描述的这类基本几何体为原型。然而,除了边界分明的几何体,自然界还为建筑师展示了其他景象,火焰弥漫的烟雾、白云边缘的丝絮、河流奔腾的波浪、甚至细胞渗透中的粉状物。它们的特征是互联、流动与开放,我们为什么不参照这类混杂、无边界的景象呢?这种消散的概念又是如何帮助建筑师设计过渡空间的?由本文作者领导的动态建筑研究组(Living Architecture Systems Group)为2021 年威尼斯建筑双年展设计的合作项目“Grove”试图解答这些问题。Grove 借鉴自然界各类消散现象,呈现一个巨大的“天幕”,创造了沉浸式数字环境。

Grove 包含一个飘带形巨型天幕和一个中庭。悬挂在椭圆形展厅上方的天幕点缀了多个柱状物,它们带有环绕式扬声器。参观者可在中庭聚集或在柱子间自由穿行。该项目的主体结构通过自动切割、热加工、机械成型方式,将材料消耗降至最低。悬挂的柱状物由数十万个独立的透明聚合物、聚酯薄膜、玻璃和膨胀聚合物组成,在参观者和周围环境间形成独特的视觉屏障。各构件根据振动规律以及不断变化边界的对称几何形进行组合。

Grove 的设计者将薄片状的原始材料组合成束,使其坚固,还可聚集成更大群体、形成网络。各构件具有柔性与稳定性,能够响应重力和气流的变化。通过设计,构件的振动效果得到放大,逼近材料跨度和稳定的极限。大面积去除体积也可保证材料的灵活度和弹性,使之自由扭曲。可拉伸的网状作品中嵌入了小的支撑杆,形成有预应力的整体架构,保证稳定性。这些开放结构的设计和制作为设计柔性和响应式建筑提供方法。

从建筑角度,Grove 项目的设计思路也为外墙和屋面提供了可选择的方案,可将这些表面看作网状散热片,或调节内外环境的分层膜布。这种追求材料极限、互动性的新型形式语言,意味着设计可以采用新的管理思路。它表现了土壤般肥沃的物质世界,取代了贫瘠的、柏拉图式的地平线感。这种理想状态是用最小的屏障来寻求对周围环境最大的参与。从设计角度,Grove 开启了身体和环境之间交流互动的全新视角。

·支持自由集会

Grove 空间为公共性自由集会设计。走进巨大、黑暗的展厅后,你会看到远处一个发光的椭圆形“水池”。这其实是投射到镶嵌在地板上的水池一样的椭圆形屏幕的投影。天幕在水池上方以不同姿态舞动,是空间的中心。闪烁的光线就像太阳在树林缝隙里游走。水池的边缘扩大成座椅,供人们休憩、聚集,分享对沉浸式空间的感受。围绕这个中心,参观者可以自由地在柱子间行走,聆听它们的细语。当你在水池边向下或向上看去,会发现若干单体组成的天幕。你会被水池边成千上万个装满液体的泪滴状玻璃容器包围着,透明液体里都含有结晶的合成细胞,像是透明的“叶子”。

俯瞰水池,你便进入了梦幻般的世界。你周围的一切,包括上方那个变换、呢喃的天幕都被投射到这个新世界的无限深处。水池中的影像描述了一个轮回,海洋般深邃的黑暗湖泊里出现一丝光线,然后又恢复黑暗。水池的物理环境被投射的图像赋予意义,充满梦想和无限可能,幻化成植物、动物和人类蓬勃的生命力量。这个影像慢慢从肥沃的生命转变为贫瘠的、沙漠般的寂静,然后再次迎来新生。

·构件交织创造柔性空间

该作品的概念是向外或内延伸,表现了交织与穿梭。向外:叶片边缘与空气交错。激光切割的半透明叶片通过分组和捆绑,使它们紧密的围绕内芯按角度排列。向内:插入悬臂支撑,并将支撑这些叶片簇的透明亚克力构件连接在一起,形成消散和柔性网络。叶片轻轻地拍动,对观众的动作做出反应。

和自然界雪花多变的几何图案一样,对称的几何图形是Grove 飘带形架构的组合依据。互相嵌套、螺旋的半透明叶片具有柔性,可在其悬挂点进行位移,因展厅内的空气流动而拉伸或收缩。架构的六边形框架与内部排列方式相协调,遵循手性规律。每个单片都有对应的旋转中心,由交替出现的向上或下延伸的构件环绕,螺旋着围绕中心旋转。相匹配的三角形连接件也包含类似的螺旋构件,这些弯曲构件的每一部分都有一束“叶子”,叶片边缘有尖刺。每片都延伸到悬臂尽头,并以振动来响应周围空气中由机械和人类动作引发的轻微变化。尖刺在叶片下收缩,形成明显的凹形轮廓。交错的尖刺结构形成了一个气流阀,当打开并放大向上的气流时,便会关闭向下的气流。相互连接的构件跟着叶片边缘一起规律地摆动,连续起伏的振动会延伸到整个架构。

·气候变化

Grove 还通过改善微环境来应对气候变化。Grove 的构思来自富饶与肥沃的自然湿地。与常规墙体不同,柔性构件可以缓慢地分解、吸收、消散力。这是一种类似水和空气的力量,它四处游走并趋于平静。

Grove 提出的再生方式,与传统建筑坚硬、封闭的墙体形成对比。Grove 的消散思想遵循1978 年诺贝尔奖得主伊利亚·普里戈金(Ilya Prigogine)的创新物理学理论。普里戈金提出了创新观点,即多层次系统如何剥离力量、放松、与周围世界关联,从而重组和自我更新。这与我们注重边界并将自己与世界隔绝的观点完全相反。相应的,正是通过互动、寻求不稳定性的尝试,我们才能设计出柔性、持久的建筑。

图1 我们将如何共同生活?我们是否将自己与周围的环境隔离开来?

图2 如果我们扩展和开放我们的边界呢?我们可以建立开放的、有生命力的边界吗?

图3 Grove 代表了一种新的聚集场所,花边状 的边界取代了坚硬的墙壁,具有非凡的耐久性和遮蔽性

·动态建筑

Grove 是动态建筑的原型之一,它参考物理世界的多种力量并模拟自然。当人们体验Grove 时,就像穿过一片昏暗的森林,能看到无数微生物、植物的生长、动物、以及其他人类在那里的痕迹。我们不孤独,空间也不空旷,而是充满各种可能性,这是Grove 项目传递的基本思想。我们与无机、有机生物的世界都有深刻的联系,应从中感受到动力与希望。

Grove 有关哲学和物理、跨越了人文与自然。它包含的柔性天幕,可以应对力的极限。在这个充满变化的时代,人类会自然的倾向自我保护。为了建造住所,人类竖立最坚固的墙壁作为边界。传统建筑一直专注在城市中创造个人领地。这强调空间内外的差异,对群体进行分类,一部分属于内部,其他群体则排斥在外。然而,分隔内外的边界可能被扭曲,走向极端,造成不必要的冲突。那些表面上保护我们的墙也会放大我们的问题。

Grove 提供的不是封闭的墙,而是飘带般的架构,构件聚集、交织、相互连接,与自然一起设计。在构建动态建筑原型时,我们超越了不透明、封闭的状态。以Grove 为例,它创造了森林般的空间,让参观者在无机、有机生物的多层次世界中思考社会生活的渗透与脆弱性。这些实验性作品所蕴含的关系便是建筑设计的形式语言。新的建筑形式语言不应自我封闭,而是促进相互交流和最大限度的互动,使之充满新生命的活力。

注:文章改编自菲利普·比斯利(Philip Beesley)《GROVE:面向活的建筑的开放系统》(GROVE: Open Systems for Living Architecture)一文,著于《人类、机器与微生物的共生》(Co-Corporeality of Humans,Machines,&Microbes)一 书,由Barbara Imhof、Daniela Mitterberger 和Tiziano Derme 共同编辑。

【英文原文】

Manifesto for Interactivity: Against Platonic Architecture | Philip Beesley

In his Timaeus,Plato described fundamental origins of the universe as embodied within a perfect sphere: " The soul,interfused everywhere from the centre to the circumference of heaven,of which also she is the external envelopment,herself turning in herself,began a divine beginning of never-ceasing and rational life enduring throughout all time."

The reductive geometries of elemental forms described by Plato lie at the core of long design traditions within built architecture.Yet,when we think of the myriad of forms that the natural world has offered architects,why should we prefer closed,pure,glossfaced cubes and spheres to tangled,dissipating,open fields? The opposite of reductive spheres and crystals could be found in veils of smoke billowing at the outer reaches of a fire,the barred,braided fields of clouds;torrents of spiraling liquids; mineral felts efflorescing within an osmotic cell reaction. Such sources are characterized by resonance,flux,and open boundaries. Seen in this nuanced way,how does this conception of dissipative form help architects build liminal space? Designed for the 2021 Venice Biennale for Architecture by the international team of the Living Architecture Systems Group led by the author,the collaborative project Grove attempted to offer practical answers to these questions.Grove drew upon the formlanguage of natural dissipative forms and translated those sources into a large,public canopy that framed an immersive digital environment.

Grove used the paradigms of dissipative structures and diffusion as guides for its design and fabrication.The structure of Grove includes a lace-like overhead canopy containing a centre void.Suspended above an elliptical gathering space the canopy is punctuated by multiple columnar forms containing omnidirectional custom speakers.Occupants can walk freely amidst the columns and gather around the centre.The structures within this project resulted in minimal material consumption -achieved by automated cutting as well as thermal and mechanical forming of expanded arrays of filamentary structures.A hovering filter environment composed of hundreds of thousands of individual laser cut transparent polymer,mylar,glass and expanded polymer elements created diffusive visual boundaries between occupants and the surrounding environment.The organisation of these components was characterised by punctuated oscillation and quasiperiodic geometries with shifting boundaries.

图4 Grove 侧 视图—表 现天幕 和柱状 扬声器

The makers of Grove worked by drawing and combining thin sheets and strands of primary materials into strong components,which were then massed together into larger groups.The massed groups crea intederconnected networks.Components were designed with reactive,poised dispositions that responded to gravity and shifts in airflow.Trembling and vibrating movement was enhanced and amplified by design that brings materials close to their limit of spanning and stability,creating measured precarity.Flexure and elasticity was retained by voiding out large surfaces and volumes,opening the components for deflection and compliance.Mesh works of relatively long tensile filaments were embedded with small compressive struts,creating tension-integrity networks carrying gentle prestressed forces,creating poise.The design and fabrication of these openwork scaffolds suggest methods for creating full-scale resilient and responsive architecture.

At the scale of architecture,the design principles shown within the Grove project might offer alternatives to the conception of enclosing walls and roof surface,reconceiving those surfaces as deeply reticulated heat sinks,and as layered interwoven membrane curtains that modulate the boundaries between inner and outer environments.A new form language of maximization and engagement implies that design may in turn embrace a renewed kind of stewardship[4].Such a role replaces the sense of a stripped,Platonic horizon with a soil-like generation of fertile material involvement with the world.This kind of optimum then seeks the utmost possible involvement with its surroundings with minimum defense.From a design perspective,Grove evokes an efflorescence of involvement and exchange between body and environment.

·Forum Supports Shared Gathering

The space of Grove provided a tangible public forum,designed for free assembly and informal gathering.When you entered the great dark columned hall housing Grove,in the distance you could see a glowing oval pool surrounded by islands of clustered sculptural fronds.Lace-like skeletal clouds spiraled upward through those floating,blooming forms.Clouds and islands were concentrated at the centre,moving in different choreographies over the pool.Shimmering light played constantly like sun edging its way around a copse of trees.The clearing at the centre of Grove was focused by a projection directed into a curved,pool-like oval screen set into the floor.The pool was bordered by a swell within the floor surface that invited lounging and relaxing along its edge.The incurving edge of the pool created a threshold where viewers gathered,assembling informally and sharing the experience of the immersive space. Around that centre,viewers walked freely amidst the columns,drawing close to each multichannel speaker to hear their individual emanating whispers and creating perceptions of an open composition determined by individual movement throughout the space.Standing and gazing down toward the pool,or reclining and looking upward,you looked into a sky of interwoven clouds and miniature islands. When you reached the pool,hanging transparent fronds encrusted with thousands of teardrop-shaped liquidfilled glass vessels surrounded you,each holding crystalline synthetic cells within their clear liquids.

Looking down into the pool,a dream-world opened up.The shifting,whispering world around and above you was projected into the infinite depths of a newly transformed shadow-world below. A continuous looping film projected into the pool depicted a cycle that moved from marine-like lagoons of deep darkness into brilliant light and back into darkness.In that depth,the physical environment was transformed by a layer of moving images,becoming a realm of dreams and possibility where presences implied in the physical elements above transformed into living forces of plant,animal and human actors.The interwoven field of evoked by this filmcycle shifted slowly from fertile life into sterile,desert-like stillness,and then into life arising again.

·Interwoven Components Create Resilient Space

The work followed a conception of architecture that extends outward and inward from boundaries,encouraging crossing and passage.Outward: tendrils and plumes interweave with surrounding layers of air.Clusters of lasercut translucent polymer fronds were arranged by grouping and bundling their angled geometries around close-fitting inner sheath structures.Inward,cantilevered resilient stays were inserted,and arrays of individual impact-resistant acrylic chevron links supporting these bundles were chained together with elastic joints to form a diagrid of corrugated mesh with diffusive,viscous performance.Leaf-like tines within each frond gently fluttered and stirred,responding to gentle air movements created by the movements of viewers.

图5 Grove 细节图—表现观众、定制的柱状扬声器和悬挂的天幕

图6 Grove 细节图—表现天幕、投影“水池”和多个柱状扬声器

图7 Grove 虫眼视图

Like the geometric systems that result in innumerable variations within natural snowflakes,a 'quasiperiodic'fluctuating geometry organized the billowing skeletal membranes floated above the ground level of Grove.The nested spiral fabric membrane was highly elastic,accommodating large displacements within its hung tentwork placement.This elastic performance was dynamic,creating infinitesimally varying stretching and contracting motions in response to air movements within the hall,and amplifying increments of pressure produced within the individual comb-cell filters.Skeletal hexagonal frames followed tiled arrangements harmonized with the inner cores.Large sections of the outer membrane showed additional chiral organization.In these sections,each tile contained a rotated core encircled by alternating upward and lower-reaching flexible curved arms,creating voided helical rosettes that spiral around their centre.Matching triangular couplers contained similar spiraling arms.Each arm of these curved skeletons carried a curving frond with extended combs of individual needleshaped mylar filaments.Each needle form was extended close to its cantilevered span limit,and reacted with trembling vibration to slight shifts in the surrounding atmosphere created by mechanical and human produced air movement.Individual filaments followed contractions latent within the lower sides of sheet-formed polyester material,creating pronounced concave profiles.Intersecting combs that follow these profiles created a toothed valving structure which tends to close against downward drafts of air while opening and amplifying upward currents.The composite structure performed as a gentle mechanical pump,amplifying upward convection.Supporting this turf-like interwoven layer,the linked spring skeletal structure followed a tracery of oscillating filaments whose continuous undulating paths extend throughout the entire canopy.

·Climate change

Grove addressed climate change by demonstrating how architecture can help to heal the environment.The construction of Grove drew its forms from the kind of fertile relationships that we can see in a natural wetland that lines a river.Instead of unintended destructive forces that come from sealed walls,resilient interwoven components can gently break down,absorb and dissipate,similar to the forces of water and air,which allows benign forces through and between separate areas while at the same time calming them.

Grove proposed a kind of regeneration that contrasts with the hard,closed surfaces of traditional urban building while still offering shelter and sanctuary.Grove's dissipative adaptation follows innovative physics revealed by the 1978 Nobel Prize-winning insights of Ilya Prigogine. Prigogine offered innovative views that explained how multiple layered systems can continually reorganize and refresh themselves by shedding forces,relaxing,and interconnecting with the surrounding world.This is far from the view that says we need to concentrate our boundaries and close ourselves off from the world.Instead,it is by encouraging sensitive interactions and by pursuing precarious gentle and unapologetically fragile dimensions of work that we can make a resilient,durable architecture.

·Living Architecture

Grove is a prototype of "living architecture" that works with nature by interconnecting and embracing the myriad forces of the physical world.When people experienced Grove,they could feel some of the sensations they do walking through a deep twilight forest,seeing the myriad of tiny organisms,plant growths,animals and the memory of other people that have passed there.The sense that we are not alone,and that space is not empty but rather full of possibility,was a fundamental sensation that the Grove project intended to impart.The message of this work was that we are deeply interconnected with the animate and inanimate world and we should feel motivated and hopeful by this fact.When we look at life as something that connects us all,we can begin to see how our world can heal,full of renewed possibility.

Grove was a philosophical and physical essay that meditates on how thresholds can be open.Grove crossed both social and natural worlds in demonstrating how thresholds can heal and regenerate.It demonstrated a model of mutual sharing.The openings within Grove offered resilient layers that handled the widest possible range of forces.In this fundamentally insecure time,there is a natural human tendency towards self-protection.This can translate into a desire to build the strongest possible walls and boundaries to create sanctuaries.Traditional architecture has been preoccupied with classical values that are concerned with making a maximum of individual territory within cities.Classical order emphasizes differences between the inside and outside of space,sorting between the groups that belong within and leaving the others "outside". Yet,boundaries that create sheltering order can be distorted and polarize us,creating unnecessary conflict.The same walls that apparently protect us can amplify our problems.

Instead of closed walls,Grove offered a multitude of gentle lace-like filtering layers gathered together,interweaving and interconnecting.By creating expanded,open thresholds,we design with nature.In prototyping "living architecture" we move past the opaque and closed.In the example of Grove this gesture opened into a forest-like glade that invited visitors to think about porous,fragile ways of sociality and livingwithin an expanded world enfolding both mineral and living beings.The intimate dimensions implied by these experimental works imply form-languages for designing buildings.Instead of valuing resistance and closure,new form-languages for architecture could foster mutual relationships and maximum interaction brimming with new forms of life.

This essay is adapted fromGROVE: Open Systems for Living Architectureby Philip Beesley withinCo-Corporeality of Humans,Machines,&Microbes,edited by Barbara Imhof,Daniela Mitterberger and Tiziano Derme.

4 交互视野 I 迈克尔·福克斯 I 刘洁、冷延鹏 译

最近,一些交互建筑项目的建造规模已经不仅超越了建筑展览作为试验台的范围,而且在材料性能、联结度和操控方式等方面也突破了我们原有的思维界限。该领域的迅速拓展得益于大量的研究人员和设计师不断地对最前沿技术的探索和应用。同时,在这一过程中,建筑行业设计和制作原型所需工具技术的易用性和经济性也起到了至关重要的作用。作为建筑师,我们上下求索,探赜索隐。尤其是交互式建筑的设计并非凭空发明,而是探索并驾驭已有技术,并将其推演至一种适合建筑语境的状态。

如今,研究交互式建筑所需要掌握的技术非常简单,以至于一个非计算机科学或机械设计专业的设计师也可以轻松地将他们的设计想法推进到原型阶段进而清晰地传达其设计意图。在整个交互设计过程中,建筑师或设计师并非单打独斗,但是他们需要掌握足够的相关学科基础知识来推进设计。这就如同尽管建筑结构设计是由结构工程师而非建筑师完成,建筑师依然需要在学校学习结构工程一样。就定义而言,交互式建筑环境需要以嵌入式计算系统和与之对应的实体构件为基础,进而通过交互的方式来实现其适应性。

·机器人技术的演变

长久以来交互式建筑的探讨语境基于之前对机器人的定义,即“由程序引导的机械代理”。然而最近我们看到建筑领域机器人技术的应用有了质的改变(图1)。

图1 机器人技术的演变:(1)标准的拾取与放置,(2)模块化机器人技术,(3)微型和纳米级机器人技术,以及(4)软机器人技术。

同时,通过机器人领域中的相关项目我们可以发现人们设计和理解机器人的方式也发生了转变。在这里,尺度变成了最重要的影响因子。如今在探讨诸如智能模块单元尺度及智能响应复杂度的变形、进化和自组织机器人方面的研究进展正在制定机器人技术发展的新标准。讽刺的是,机器人技术的进步往往被视为一个交叉领域,其尺度的改变也受到材料科学和生物仿生学发展的重要影响,而这些发展又同时很大程度上影响着建筑设计的其他方面。总体而言,研究人员不再从“有腿”机器人的视角来研究机器人运动,而是开发由模块化部件组成的机器人,作为一个系统来解释和表达信息[1]。

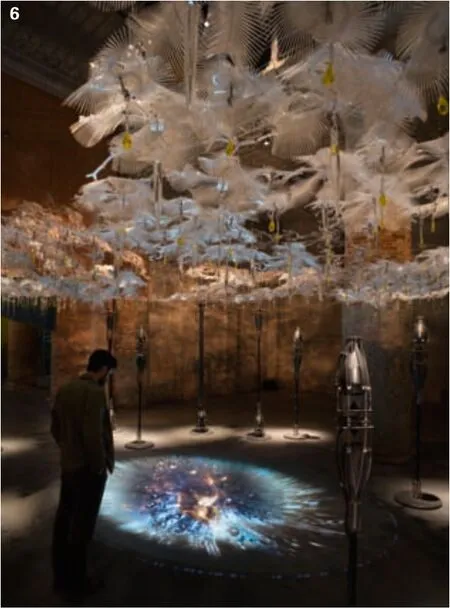

在以下学生项目中,模块作为模块化自主机器人组件被创建并应用于不同规模大小的空间制作场景中(图2、图3)。物理模型展示了实际的机器人技术、结构与材料。学生项目中也探讨了几种去中心化控制的策略,规定了系统的各个部分应该采用何种个体行为,以及如何通过各个模块之间的局部交互产生全局行为。这些项目成功地展示了多种机械设计、运动和控制的策略。

图2 使用模块化机器人技术的建筑应用

图3 机器人运动的状态变化

在软体机器人系统研究方面,也许(与建筑)最相关的研究是软体与可变形结构的科学原理和技术实现。从机器人技术的角度来看,柔性和可变形结构在处理模糊和动态的任务条件、在粗糙地形中的运动以及与活体细胞和人体物理接触等方面扮演着至关重要的角色。此外,软体材料对于自我修复、生长和自我复制等相关课题的研究也非常重要。

·不断发展的影响

直到最近,我们看到机器人变得越来越小,但其仍然依赖于最微小的传统机械部件。各类物质所表现出来的丰富可能性使得传统机械范式在还未充分展现其特性的时候就已然显得过时了。正如迈克尔-温斯托克(Michael Weinstock)诗意地指出,“材料不再服从于强加给它的形式,而是服从形式本身的起源”[2]。

为了更加深入理解,我们需要了解生物体生长和发展的过程。这一研究领域被称为发育生物学,包括生长、分化和形态生成。一个有用的定义依赖于一个更大的可以涵盖所有设计的系统框架。在这个层面上,生物仿生学从本质上影响着材料的表现性能和操控尺度,其与在设计和建造环境方面应对迭代需求的创新材料有着异曲同工的作用。

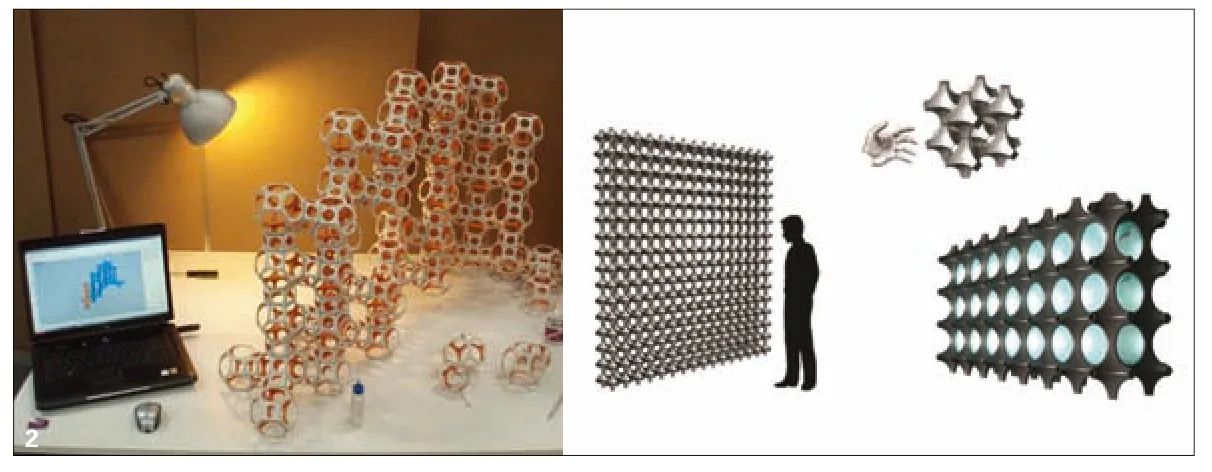

基于这种生长和发展的逻辑系统,我的学生构建了许多建筑空间设计。其中一个项目选择将骨骼重塑的过程应用于建筑表皮系统(图4)。具体而言,细胞会重建结构以适应它所承载的负荷;骨头在骨折愈合后可以改变其物理形状,以充分承载负荷。这样一个不断周转的过程动态地保证了骨架在一段时间内的机械完整性。

图4 模仿骨质重塑的过程

·用户控制

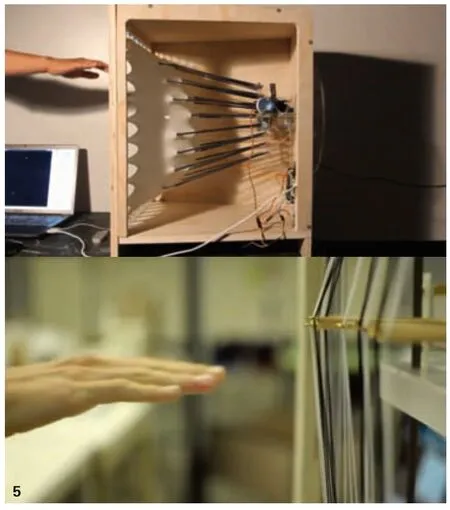

年轻的设计师们已经开始意识到他们有可能感知任何想象中的东西。如今的传感器几乎可以辨别任何东西,从复杂的手势到二氧化碳排放再到头发的颜色。一个互联的数字世界意味着,在拥有感知能力基础之上,数据集(从互联网使用习惯到交通图谱和人群行为)可以成为交互建筑环境的驱动力。在对人相关因素的感知方面,交互界面设计领域的最新发展终将发挥重要作用。将交互界面嵌入建筑中,让用户与环境交互,可能很快就会成为一种普遍现象,我们相信手势语言是实现真正物理交互的最有力的控制手段(图5)。

图5 使用Leap 传感器的精确手势控制的学生模型

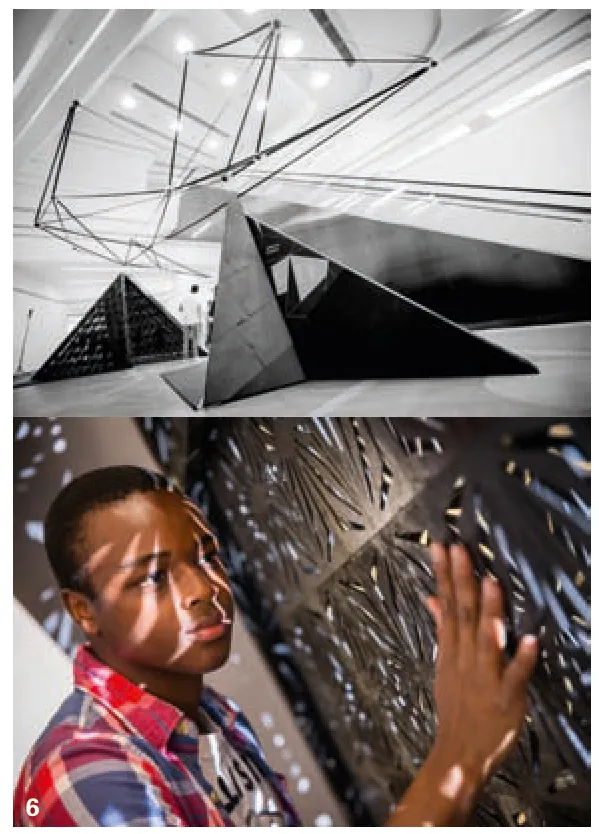

多点触控硬件技术的进步对建筑学来说意义重大,因为在许多情况下,用来控制界面的手势与在现实空间中用对实体物体进行这些相同操作的手势最为相似。对建筑构件和物理空间本身的操作更适合由其用户采用手势,而非设备、语言、认知等方式完成实体操控(图6)。

图6 大型交互展览,用近似手势控制行为

·增强型仿生学技术

由此,前文所简述的无论机器人技术还是新材料的应用均表现的是一种小尺度操控的整体性适应行为。下文所列举的建筑立面设计学生作品则更强调通过控制机器人而间接实现的增强型仿生学技术。

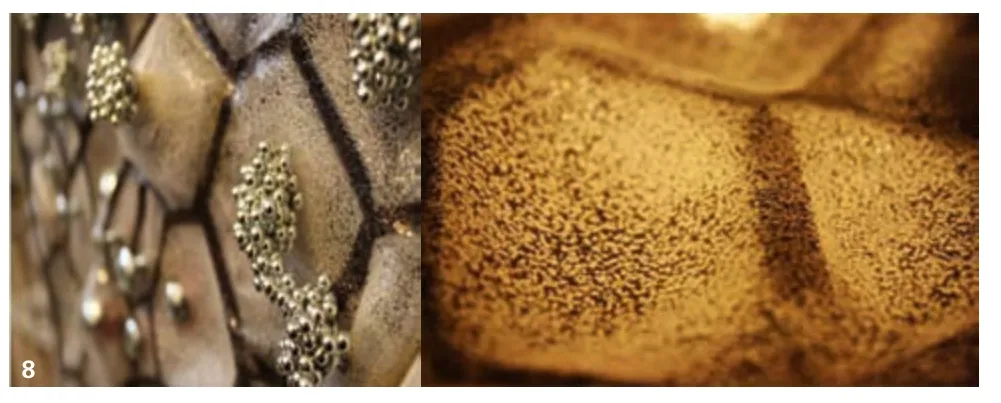

在增强型粘液霉生物幕墙(图7)设计中,设计希望使用具有某种特定特性的材料以尽量减少能源的使用和机械的复杂性。通过机械操控调节霉菌培养基和食物的数量和位置肌理,从而控制立面纹理的生长周期及美学表现。

图7 增强型粘液霉生物幕墙

西西弗斯幕墙系统(电磁强化立面)的实现基于对丙烯酸表皮上的电磁阵列的特定控制(图8)。通过控制网格使表皮上不断脱落的微型金属球能够在表面上聚集。它实现了一种通用机器人控制的效果,能够在受到系统自然随机效应的影响后,在相同的控制效果下,创造出略微不同的肌理纹路。

图8 增强的电磁立面(西西弗斯立面)

·催化剂设计

这里值得一提的是这种被控制但又在另一层面自控的催化剂设计系统有可能重新定位设计师的角色。不同于分毫不差地确定建筑对人和环境需求的响应表现,该系统呈现的结果是出乎意料的,建筑被允许以一种自下而上设计的角色来参与自己的塑造。正如戈登-帕斯克所说:“我认为,建筑师在这里的作用与其说是设计建筑或城市,不如说是催化它们:为它们的发展采取行动”[3]。

建筑师应该知晓众多领域的先进技术,并从中推断哪些技术有可能进一步构建他们职业的未来愿景。虽然在编程、生成式设计、进化式设计等概念出现之后,这种想法在建筑界早已存在,但这次所带来的可能性却又似乎非常与众不同,因为它们有潜力对建成后的建筑依然产生影响作用。

注:本文的英文版将会于袁烽、尼尔·林奇、比纳兹·法拉利编辑的《交互未来》一书中出版。

【英文原文】

Interactive Horizons I Michael Fox

In the recent past a number of interactive architecture projects have been built at scales that both move beyond the scope of the architectural exhibit as test bed and push the boundaries of our thinking in terms of material performance,connectivity,and control.Fueling the growth of exploration in this area is the number of researchers and designers working within the rapidly evolving technologies.Perhaps equally as important as the rapid advance of the technologies necessary for interactive design is the technological and economical accessibility of the design and prototyping tools available to the profession of architecture.We in architecture usurp what we can.Designing interactive architecture in particular is not inventing,but appreciating and marshalling the technology that exists,and extrapolating it to suit an architectural vision.

The requisite technologies are now simple enough to enable designers who are not experts in computer science or mechanical design to prototype their ideas in an affordable way and communicate their design intent.Architects and designers are not expected to execute their interactive designs alone;they are expected rather to possess enough foundational knowledge in the area to contribute.In the same way that architects need to learn structural engineering in school,it is rarely assumed that architects will do the structural calculations for the buildings they design;that work is carried out by professional structural engineers.As a matter of definition,interactive architectural environments are built upon the convergence of embedded computation and a physical counterpart that satisfies adaptation within the framework of interaction.

·The Evolution of Robotics

The approach to interactive architecture has relied on an historical definition of robotics as a "mechanical agent guided by a program".In the recent past,however,we have seen a dramatic evolution of robotics as applied to architecture (Fig.1): (1) standard pick-and-place,which has been applied to numerous architectural systems and façade systems in particular,(2) modular robotics,(3) micro and nano-scale robotics,and (4) soft robotics.

The landscape of projects that makes up the field of robotics is also seeing a shift in the way that we both design robots and understand robots.Here,the overriding influence is that of scale.

Current advancements in metamorphic,evolutionary,and self-assembling robots,specifically dealing with the scale of the building block and the amount of intelligent responsiveness that can be embedded in these modules,are setting new standards for the construction of robotics.

Ironically,advancements in robotics are viewed as a transitional area where scale is also heavily influenced by the same developments in material science and biomimetics that are also heavily influencing other areas of architectural design.In general,researchers are moving away from looking at robotic locomotion through "legged" robots and are instead developing robots made up of modular parts that work as a system to interpret and act upon information[1].

In the following student projects,modules were created as modular autonomous robotic components and applied to scenarios of space making at various scales (Fig.2,3).Physical models demonstrated actual robotics,structure and materials.Several strategies for decentralized control were explored dictating how individual parts of a system should behave and how local interactions between individual modules can lead to the emergence of global behavior.The projects successfully demonstrate various strategies for mechanical design,locomotion and control.

Perhaps the most relevant research lies in the area of soft robotics which is the science and engineering of soft and deformable structures in the robotic systems.From a robotics standpoint,soft and deformable structures are crucial in the systems that deal with uncertain and dynamic taskenvironments,locomotion in rough terrains,and physical contacts with living cells and human bodies.Further,soft materials are also necessary for the more visionary research topics mentioned above such as self-repairing,growing,and self-replication.

· Evolving Influences

Until recently,we have seen robots getting smaller and smaller yet still relying on the tiniest of conventional mechanical parts.The possibilities from the vantage point of a materiality make the mechanical paradigm seem dated,ironically before it ever had a chance to fully manifest itself.As Michael Weinstock poetically states,"Material is no longer subservient to a form imposed upon it but is instead the very genesis of the form itself."[2]

Diving a bit deeper requires an understanding of the process by which organisms grow and develop.This area of study is called developmental biology and includes growth,differentiation,and morphogenesis.A useful definition relies on a framework of recognizing the larger systems in which all design resides.Biomimicry then at this level is intrinsically tied to such performative aspects of the operational scale and the inherent behavior of materials,as well as the role that innovative materials may play in designing and building environments that address changing needs.

My students have done a number of projects in which scenarios of growth and development have been applied to systems that make up architectural space.One of the projects uses the process of bone remodeling as applied to an architectural building skin (Fig.4).In particular,the cells will rebuild the structure to adapt to the load it carries;a bone can change its physical shape after a fracture that heals out of position,so that the load is adequately supported.Such a process of continuous turnover dynamically ensures the mechanical integrity of the skeleton over time.

·User Control

Young designers have started to realize that it is possible to sense anything they can imagine.Sensors available today can discern almost anything from complex gestures to CO2emissions to hair color.An interconnected digital world means,in addition to having sensory perception,that data sets—ranging from Internet usage to traffic patterns and crowd behaviors—can be drivers of interactive buildings or environments.In terms of a resolution with respect to the sensing of human factors,recent developments in the area of interface design will eventually play a major role.It may soon be commonplace to embed architecture with interfaces to allow users to interact with their environments and we believe that gestural language (Fig.5) is the most powerful means control through enabling real physical interactions.

Advancements in multi-touch hardware technology is significant to architecture because in many cases the gestures used to control an interface are the most similar to gestures that would be used to replicate these activities in real space with tangible objects.The manipulation of physical building components and physical space itself is more suited to gestural physical manipulation by its users instead of control via device,speech,cognition,or other (Fig.6).

·Augmenting Biomimetics

What has been outlined so far are advancements in both robotics and new materials whereby the adaptation becomes much more holistic,and operates on a very small internal scale.In the following series of student projects focused on façade designs,biomimetic systems were augmented with a secondary means of robotic control.

In Augmented Slime Mold Bio-Façade (Fig.7) the goal is to use materials with specific characteristics in order to minimize energy use and mechanical complexity.The growth cycle,and consequently aesthetic effects and patterns,are controlled through the robotic manipulation of depositing and retrieving a regulated texture of growth medium,and food quantity,to specific locations.

The Sisyphus Façade system (Augmented Electro-Magnetic Façade) relies on the specific control of an electromagnetic array on the acrylic skin (Fig.8).Through control of the grid,tiny metallic balls that are constantly falling down the skin are allowed to congregate on the surface.The effect has a sense of generalized robotic control that is influenced by the natural random effects of the system creating a slightly different pattern every time with the same controlled effect.

· Catalyst Design

The important thing here is that such systems that are controlled but yet control themselves on another level have the potential to reposition the role of the designer.What results is the emergence of unexpected designs rather than an architecture that literally interprets and responds to human and environmental desires;the architecture is allowed to take a bottom-up role in configuring itself in a malleable way.As Gordon Pask states "The role of the architect here,I think,is not so much to design a building or city as to catalyze them: to act that they may evolve."[3]

Architects should be informed of the many areas of technological advance to understand what is possible to extrapolate from these ideas in the creation of a vision to direct the future of their profession.While such ideas have been around for quite some time in the architectural world in terms of scripting,generative design,evolutionary design etc.,the possibilities seem very different -they have the potential to affect the architecture itself after it is built.

A version of this paper will be published in the bookInteractive Futuresedited by Philip Yuan,Neil Leach and Behnaz Farahi.

5 交互式建筑:建筑学的新理论疆域 I 亨利·埃克斯 I 何沐菲 译

自从开始居住在建筑物中,人们就希望改造居住的建筑物从而适应自己不断变化的需求和居住条件,而技术和材料的进步使得这种改变越来越容易。随着 “交互式建筑”这一概念的出现,更多的“智能”和“自主性”被添加进了建筑领域,这一改变在很大程度上丰富了改造建筑的可能性——以至于人们需要改变自己对于“建筑”本质的理解。这篇文章将讲述关于 “交互式建筑 ”这一主题的一些思考和想法。

“交互式建筑”可以被理解为多种含义,一些相关概念都体现了与其类似的含义,但又不尽相同:如建筑自主系统、智能家居、感知建筑、自适应建筑、动态建筑、智能建筑和可移动建筑。它们有一个共识,即建筑必须适应不同的需求,从而可以更好地达成其目的。虽然引入另一个术语有一定的风险,但我们可以把所有这些技术一起称为 “响应式建筑”。而所有响应式建筑都应该具有以下共同点:

·集成型适应:建筑的一部分可以被改变,并且这些改变从一开始就被纳入建筑组成中。例如:可移动的墙板、百叶窗或座椅排布。综合性适应预测了未来将进行的变化,并通过组成部件的设计使改变更加容易。

·感应:存在某种监测系统,可以检查建筑物的状况。例如:运动传感器、温度计、光传感器等等。

·决定:对于建筑 "可响应部分" 的变化的执行和实践。本文开头提到的大多数技术中,决定部分都以某种自动化的形式存在,最常见的案例有遮阳系统、自动门等等。然而,在自适应和可移动建筑中,感知和决定的主体也可能是居住者本人。

在确定了共同特征之后,我们现在可以更准确地说出交互式建筑是什么。那么下一步需要思考的是,交互式建筑如何区别于其他响应式建筑?

解决这个问题的关键字显然是 "交互"——即两个代理主体之间的信息交流。这里的代理主体可以是人,也可以是自动或机械系统,但在大部分情况下,我们谈论的是人与建筑之间的交互。由于在信息的基础上,变化可能发生在一个或两个代理主体中,因此,信息交流必须是有意义的。

其他大多数响应式建筑旨在尽可能消除或减少信息交流。例如,自动滑动门对接近门的身体作出反应。它们是反应式的,即完全基于接近传感器的输入来进行开门和关门的动作。这也意味着在许多情况下,即使附近的人只是路过而没有进入的意图,门也会随之打开。另外,一些更先进的自动门系统已经将“建筑智能”应用到系统中,从而判断出路人和意图进门的人。然而,参与交互的人是“被排斥在外”的,他们不能主动表达自己想要进入建筑物的愿望。

在这个自动门系统中,只有允许或不允许进入两个操作,其中的交互也只限于一个方面:门是否应该打开。但是,对于遮阳设备等,交互过程将会变得更加复杂。遮阳设备基于室内光照相关的客观标准作出相应反应,比如通过对阳光直射量的限制避免房间中过热和眩光。然而,在室内的人也有主观愿景,比如:他们是否想看到外面的风景,遮阳板升起或落下时是否可以通风换气,遮阳设备在运行时是否会产生很大的噪音,百叶窗是否移动过度、太快或太慢,它是否可以由人控制等等。因此,遮阳系统的感应和反馈的内容都要比自动滑门的情况多得多。另一个因素就是人的数量:每个人对于舒适或好的都可能有不同的偏好,所以人的这些需求也必须在一个公平的系统中得到平衡和满足。

自动滑门、遮阳设备和空调等普遍被归于建筑服务系统,因此,它们一般以自己的首要功能被人们认知。在大多数情况下,人们并不认为这些系统需要更多的交互,并与居住者进行信息交流。但正是由于这种对于 “服务”的观念,才使得这些系统从属于建筑自动化系统、智能家居、智能建筑等类别。

空调和遮阳设备并不占据我们的个人空间,它们位于我们生活和工作的外围空间。而自动滑门相对来说和我们的身体体验结合更为紧密(这种情况很容易想象,比如当你想进去时门却没有打开,或者当门关闭时你却还在室内)。不过,如前面所论证的,和自动门的交互是相当有限和简单的,稍后我们将讨论一个例子来讲述不同的情况。

当交互物体开始占据我们的个人空间时会发生什么?这种情况下,交互过程就会发生相当大的变化。让我们以来自鲁汶大学建筑学院Andrew Vande Moere 所领导的研究[x]设计小组中博士生Alex Nguyen 的工作作为一个具体的例子。Alex Nguyen 开发了一种可移动的墙板,可以自主地改变它在空间中的位置。该墙板的尺寸大约为:宽度1.5m,高度1.8m,厚度0.3m,它的尺寸与人体尺度较为接近。这个墙板可以放置于任何位置,因此它既可以作为一个侧墙,也可以位于某个空间的中心。基于被放置的位置,它可以改变自己的特性——可以成为座椅排布的背景、工作区域的分隔,或者引导人移动的屏障(图1)。

图1 博士研究项目 "人屋交互的建筑协调"(注:源自鲁汶大学建筑学院研究[x]设计组(2022))

为了项目完整叙述,在这里必须说明面板的移动是被远程控制的(所谓的“绿野仙踪”的控制系统)。这个控制系统可以达到此墙板的设计目的:由于在墙板附近的居住者的视线范围内没有远程操作者,所以在居住者看来,就好像是墙板在自己移动。

我们在传统的建筑设计方法中非常了解,墙板在空间中的静态位置可以促进某些空间和功能的安排。此外,可以放置在不同位置上的可移动墙板也不是新想法,这种灵活的空间隔断已经存在了很长时间,并在许多地方使用。所以,对于在一个空间中不同场合被放置在不同位置的墙板,人们已经司空见惯,并且不认为有任何奇怪或不寻常的地方。

可以说,游戏规则的变化之处在于,墙板是可以自主移动的。一个可以被放置到不同地点的普通墙板是一个由人们操纵的被动物体,人们将自己的意志强加于该物体上。然而,在墙板自我移动的情况下,意志力被转移到了墙板上,即墙板获得了代理权(代理权,即一种能力,可以自主为自己决定,参与对外部世界的操纵,并进行交流)。如前所述,墙板的尺寸和人体尺度比较接近,这意味着移动的面板与同一空间中的人有一种非常直接的物理关系——它成为一个可以与我们碰撞的物体,引导我们的路径和视野,并占据我们可能的运动空间。于是,它不再是空间中那种被看到然后被忽略的物体,而成为了空间中的另一个生活表演者,人们将不再忽视它的存在。

在物理层面上,人和物体之间会有相互作用。例如,Alex Nguyen 在项目中,研究了诸如“点头”这样的交互行为,从而探索如何对墙板进行微调。人们在与物体交互的时候,对物体的决策机制几乎没有洞察力,对他们来说,物体的决策就是一个黑盒子。然而,为了使其有意义,他们很可能将“意图性”(由美国哲学家丹尼尔·丹内特定义)归于交互对象。当我们把交互式建筑看成是由许多交互式物体共同组成的一个协调的整体时,设计或组成这个由相关交互物理组成的整体就需要叙事设计——通过讲述有意义的故事,使人们对交互式建筑的体验更加具有连贯性。

Alex Nguyen 的移动墙板非常直接地表明了,在建筑学中,我们缺乏经验、理论、词汇和设计传统来处理像自动移动的墙板这样简单的交互案例。虽然目前还很难想象,但是进一步来说,当这样的物体越来越多并成为建筑环境的一部分时又会发生什么?在我看来,它的确将会发生——因此作为建筑师,我们在掌握和控制这些问题上,正在面临挑战。

总结一下,未来的任何对交互式建筑的解释都应该扩展我们的建筑词汇:包括“代理”、“意图”、“系统动力学”、“模拟”、“预测”和“叙事”等现在我们的建筑语言中还缺乏这样的术语,如果没有它们,我们将很难理解交互式建筑的潜力和未来。

【英文原文】

Interactive architecture: A new theoretical frontier for architecture I Henri Achten

Ever since people inhabit buildings,they desire to change or adapt the buildings to suit their changing needs and conditions.Advances in technology and materials have made such changes increasingly easily.With the advent of"interactive architecture",more intelligence and autonomy is added,which can dramatically change the possibilities of changing buildings -up to the point that we must revise our understanding of architecture itself.This essay outlines a number of considerations on the topic of "interactive architecture."

The term "interactive architecture",is understood in a wide variety of meanings.Other labels such as Building Automation Systems,Smart Homes,Sentient Buildings,Adaptive Buildings,Dynamic Buildings,Intelligent Buildings,and Portable Buildings,capture related intentions,but are not identical.They all share a common understanding,that buildings must be adaptable to better serve their purposes.At the risk of introducing yet another term,let's call all these technologies together "Responsive Buildings".All responsive buildings have the following in common:

Integrated adaptation: parts of the building can be changed.These changes are incorporated from the outset in the building (parts).Examples are movable wall panels,window blinds,or seating arrangements.Integrated adaptation anticipates future changes and makes it easier through the design of the parts.

Sensing: some kind of monitoring system that checks the conditions of the building.Examples are movement sensors,thermometers,light sensors,and so on.

Deciding: setting into action the changes that need to be made for the adaptable part(s).Most technologies mentioned at the start of this text,have this in some automated form.In most examples we see this in the handling of shading systems,automatic doors,However,in the case of Adaptive and Portable Buildings,the one who senses and decides may also be the inhabitant.

With the common characteristics identified,we can now more precisely say what interactive architecture is about.How does interactive architecture distinguish itself from the other responsive buildings?

The keyword obviously is interaction.Interaction is an exchange of information between two agents.The agents can be people,but also automated or mechanical systems.In many cases,we talk about the interaction between people and the building.On the basis of the information,some changes occur in one or both agents.Thus,the information exchange has to be meaningful.

Most other responsive buildings aim to eliminate or minimize the information exchange.For example,automatic sliding doors react to proximity of a body to the doors.They are reactive.They will open and close the doors solely based on the input of the proximity sensors.This also means that in many cases,they will open the doors,also if the person nearby is just passing by and has no intention to enter.More advanced automatic door systems already apply some intelligence to determine who is a passer-by and who wants to pass through the doors.Nevertheless,the person involved in the interaction is outside the loop;he or she cannot communicate a desire to enter the building.

In the case of doors allowing access or not,the interaction moment is limited to one aspect: should the door open or not.With shading devices,for example,it becomes more complex.Shading devices respond to objective criteria like limiting the amount of direct sunlight to avoid overheating and glare.The people in the interior however,also have subjective criteria:do they want an outside view? Is it possible to ventilate with the shades up or down? Does the shading device make a lot of noise when in operation? Does it move too much,too fast,or too slow? Can it be controlled by the people or not? Thus,the repertoire of both intentions and responses is much larger than the case of automatic sliding doors.Another factor is the amount of people.Each person can have different preferences what they feel is comfortable or nice,so accommodating these desires also has to balance out in a fair mix.

Things like automatic sliding door,shading devices,and air-conditioning are perceived as building services.Thus they are often seen as primarily functional.In most cases there is no perceived need of these systems to be more interactive and engage in an information exchange with the inhabitants.It is exactly because of this "servicing" perception,that such systems fall in the categories of Building Automation Systems,Smart Homes,Intelligent Buildings,and so on.

Air-conditioning and shading devices do not occupy our personal space.They are located in the periphery of the space where we live and work.An automatic sliding door is already much closer related to our bodily experience (something which you can verify very easily when the door does not open when you want to enter,or when it closes and you are still in the door space).Still,as argued earlier,the interaction moment with a door is rather limited and simple.Later we will discuss a hypothetical example how this could be different though.

What happens,when the interactive objects start to occupy our personal space also? Things then change quite dramatically.Let's give a concrete example,from KU Leuven,Faculty of Architecture in the Research[x]Design group headed by Andrew Vande Moere,concerning work by PhD student Alex Nguyen.Alex Nguyen has developed a moveable wall panel that can autonomously change its location within the space where it is placed.The panel measures roughly 1,5m width,1,8m height,and 0,3m thickness,so it has dimensions that are closely related to the human body.It can position itself in any arbitrary location,thus it can act as a side wall,but it can also be located in the centre of the space.Given its position,it therefore changes its character as a backdrop for a seating arrangement,a divider for a work area,or a barrier controlling the movement of people (Fig.1).

For completeness sake,it must be stated that the movement of the panel is controlled remotely (a so-called Wizard of Oz setup).For all purposes though,since the human operator is out of view of the people inhabiting the same space as the panel,it is as if the panel moves on its own accord.

The static position of the panel in the space facilitates certain spatial and functional arrangements that we understand very well in our traditional architectural approaches.Also,the fact that it is a moveable wall panel that can be on various positions is nothing new.Such flexible space dividers are around for a very long time and in use in many places.Having a panel that is found on different occasion on different locations is not deemed strange or extraordinary in any way by people in that same space.

Where the game changes,so to speak,is when the panel is moving by itself.A regular panel that can be placed to different locations is a passive object manipulated by people,who are imposing their will on said object.In the case of the self-moving panel,the will is transferred to the panel.In other words,the panel obtains agency (agency: the ability to autonomously decide for yourself,engage in manipulations of the outside world and have communications).As stated earlier,the size of the panel is closely related to the size of a person.That means that the moving panel takes on a very direct corporeal relationship with the people in the space.It becomes an object that can collide with us,direct our path and vision,and which occupies the space of possible movement.Suddenly,rather than being the object in the space that can be seen and then ignored,it becomes yet another actor in the space,and something surely not to be ignored.

On the level of the object itself,there will be interactions between the people and the object.In the research by Alex Nguyen for example,an interaction aspect like nudging is investigated to see how this can afford micro-adaptations of the wall panel.People interacting with the object have no insight in the decision mechanisms,for them it is a black box.To make sense of it however,they will most likely attribute intentionality (as defined by the American philosopher Daniel Dennett) to the interactive objects.When we look at interactive architecture as an orchestrated whole of many interactive objects together,then designing or composing this whole of related interactions requires the design of narratives-meaningful stories that give coherence to our experience with the interactive architecture.

The moving wall panel by Alex Nguyen demonstrates very directly,that in architecture we lack the experience,theory,vocabulary,and design tradition to deal even with such simple examples as a self-moving wall panel.What happens when such objects increasingly become part of our built environment is at the moment quite unimaginable.That it will happen,seems certain to me -thus as architects we face to challenge to take these matters in our own hands.

To conclude,any future explanation of interactive architecture should expand our architectural dictionary to include agency,intentionality,system dynamics,simulation,prediction,and narratives.Such terms are today lacking in our discourse,and without it,we cannot begin to understand the potential of interactive architecture.

6 表演与交互设计的新型建筑实践 I 鲁伊里·格林 I 徐占一 译

数字网络媒体、智能材料、机器人和人工智能等领域的融合,正在创造新形式的人工智能体,使我们的建筑环境充满活力。这些进步正在催生全新的跨越建筑、艺术、设计、表演和工程学的创意实践形式。从管理城市基础设施性能的传感器网络,到响应人类居住和环境条件的建筑系统,再到提供个性化体验的情境感知可穿戴和移动技术,我们与周围环境接触的媒介规模各不相同。如同一个数据量丰富的“日常剧场(theatre of the everyday)”供人互动,同时这样直观的通信服务也正在塑造着从个人到全球的社会关系。源于这种对社会、空间和技术关系的戏剧性重构的理解,伦敦大学学院(UCL)的巴特莱特建筑学院(Bartlett School of Architecture)于2017 年推出了表演与交互设计(DfPI)作为建筑学硕士课程,以批判性地参与这些加速的转变。课程的核心原则是通过对新兴技术的解构,以共生设计的理念创造表演空间和在其中的表演。

计算的纠缠

经典的学科制度规范出纯粹而稳定的知识分支,并进行合理的划分和组织。但实际上,学科类别是易变的、具有历史偶然性的分类,时而增长时而萎缩,时而异质时而分裂。在传统的机构模式中,当各部门发现共同的挑战时,多学科的方法将问题分解成子部分并由学科专家来解决。这种分割会导致研究的地域化,并且更容易将学科间的传统隔阂增强而非打破。

在早期人工智能(AI)和自主机器人的多学科发展的历史中,可以看到这种做法阻碍了研究进展的案例。机械、电气和计算设计的挑战被分解,并作为独立的模块问题来逐步处理(Brooks,1999)[1]。社会科学(如心理学)的纳入则进一步将各研究孤立开,使得人文社科和数理科学之间的对话不足。菲尔-阿格瑞(Phil Agre)对早期人工智能研究的批判,阐明了具有自我强化概念模式的学科结构是如何限制了新兴领域内自我批判的范围。他描述了 “学科分类文化,比我们意识到的更深”,并且“仅使用先有领域的解决方法是几乎不可能得到激进的突破。”(1997)[2]

科目分项在本质上几乎是保守的,因此近几十年来,交叉学科(inter-disciplinary)的方法开始流行,以创造富有成效的合作空间;各个学科在不同程度上可以重叠,分享方法和内容,并且与多学科方法的非部门化性质相比,交叉学科研究整合了各种实践,其动机通常是共同认为现有的工作模式无法或不便于应对新的挑战。更具反思性和批判性的交叉学科还可以进一步推动在认识论层面的关注,揭示固有的结构(如自我强化的概念模式)和学科关系。当学科实践之间的角色和界限变得难以区分时,一些从业者就会完全超越学科,寻找非离散的历史知识组织的模式。

在《设计与科学》杂志的首篇文章中,建筑师兼研究员Neri Oxman 认为 "知识不能再被学科为边界归类,也不能以学科为边界由内产生,而是完全纠缠在一起"(2016)[3]。她指出麻省理工学院媒体实验室使用 "反学科(antidisciplinary)"一词来证明其无视知识的体制分支,大力参与复杂交织的主题。值得注意的是媒体实验室从麻省理工学院的建筑学院中产生,孵化出的合作在当时远远超出了建筑学的传统主题。它的创始人尼古拉斯-尼葛洛庞帝(Nicholas Negroponte)在一次简报中阐述了实验室的议程,他将媒体实验室描述为 “一个为背景迥异的人们同时使用和发明新媒体的地方,在这里,计算机本身被视为一种媒介——人和机器的通信网络的一部分——而不仅仅是一个人坐在前面的物体”(Rowan,2012)[4]。然而,对于计算机的理解并不是一个新的想法。在媒体实验室成立之前的十年中,计算机作为媒介的概念一直在吸引着寻求新表达形式的艺术家。早期的例子包括1968 年在伦敦当代艺术学院举办的 “控制论的偶然性”(Cybernetic Serendipity)展览,以及1970 年威尼斯艺术双年展上弗里德-纳克(Frieder Nake)、乔治-尼斯(Georg Nees)和赫伯特-弗兰克(Herbert Franke)的计算机生成图形作品的展示。

在讨论学科性的背景下,媒体艺术的出现是很重要的,因为它代表着艺术中最鲜明的跨学科案例。在网络化和开源社区的支持下,不断扩大的计算知识推动了可互用工具的发展,这些工具融合了以前不同的声音和音乐制作、插图和图形、运动和表演、生物学和机器人学、装置和建筑设计的实践。这种计算的流动性具有消解学科边界的效果,不仅发展了现有实践的混合形式,而且还出现了根本性的新实践形式。这就是我在交叉学科(interdisciplinarity)和跨学科性(transdisciplinarity)之间做出的区分。

跨学科项目的基础

DfPI(Design for Performance and Interaction)的构想始于建立一个由从事表演、媒体和空间实践的巴特莱特核心成员组成的工作组[5]。同时,我们致力于成为伦敦领先的表演和互动专项工作室,身体力行了植根于建筑方法论的跨学科实践。这些工作室包括Umbrellium,Bompas and Parr,Scanlab Projects,Stufish 和Jason Bruges Studio。不同于伦敦大学布鲁姆斯伯里(Bloomsbury)校区典型的紧凑型工作室环境,位于Here East的校区是2012年伦敦奥运会的前媒体综合体,为创意和技术机构重新改造后提供超过一百万平方英尺的多功能空间。与该设施相邻的是哈克尼威克(Hackney Wick),聚集了欧洲最密集的艺术家工作室。这种多样化的创意和技术生态系统是巴特莱特与伦敦大学工程科学学院合作的理想条件,他们将在Here East 驻扎并开发新的教育课程和研究,以从这一背景中受益。

与DfPI 的核心宗旨相一致的是,创造表演空间和创造在其中的表演可以是共生的设计活动,我们不仅在设计课程方面发挥了积极作用,而且还设计了课程中的设施。核心设施包括一个带有剧院灯光和舞池的大型 “黑匣子 ”工作室、12 通道环绕声室、“人造天空 ”灯光工作室、带有高性能GPU 计算的虚拟和增强现实工作室,以及一个有330 座的多功能礼堂(图1)。该校区的所有研究人员和项目组都可以使用最先进的数字制造设施,包括数控制造设备和工业机器人。UCL 的所有机器人研究也都从校园周围的小块区域转移被安置在这个宽敞的新场地,使巴特莱特和工程科学学院能够分享其用于制造、检查和测试的大批量机器人设备,以及计算机科学目前在自主多代理移动机器人和手术机器人方面的研究成果(图2)。这样的设施在英国是独一无二的,在国际上也很少有类似的条件,这为建立一个跨学科的项目提供了非常有利的环境。

图1 Here East 设施的激光雷达扫描图,由ScanLab 项目拍摄。上面是一个大礼堂,下面是专门的研究实验室空间。

图2 英国伦敦大学学院巴特莱特建筑学院表演与交互设计硕士项目互动装置原型设计作品Phonon(学生:Luyang Zou,Yildiz Tufan)

结论

www.interactivearchitecture.org 官网记载了有关工作的详细信息,以及通过这一独特的跨学科教学法实验而产生的理论讨论。[6]

英国在历史上一直保持着严格专业认证的垂直建筑教育模式。然而从我们开始看到专业课程相交叉的需求,特别是在研究生阶段,建筑学在历史上一直保持着艺术和工程之间的整体特性,虽然随着设计和建造建筑环境的复杂性增加,对专业化的要求越来越强烈,我们的课程并不遵循这一呼吁,而是抵制分门别类的策略,利用交叉学科扩大建筑作为一种创造性实践的内容。

编码、电子传感和机器人驱动、动画、数字模拟和制造技术方面的知识使学生能够实现物理和虚拟原型,并在公共场合进行测试,包括泰特不列颠画廊(Tate Britain Gallery)、巴比肯中心(The Barbican Centre)和奥地利林兹艺术节(Ars Electronica)。这些材料以及与新兴技术的接触鼓励了对塑造技术设计的意识形态、隐藏的假设和价值观的批判性反思。我们相信,这种材料的实践和批判性的参与为驾驭当今复杂的文化、技术和社会经济景观提供了一种有意义的手段。

【英文原文】

Emerging Architectural Practices of Performance and Interaction Design I Ruairi Glynn

Converging fields of digital networked media,smart materials,robotics,and artificial intelligence,are creating novel forms of synthetic agency that animate our built environment.These advances are precipitating entirely new forms of creative practice that span across architecture,art,design,performance and engineering.They span from the scale of urban sensor networks governing the performance of our city infrastructure,to building systems responding to human occupation and environmental conditions,to context-aware wearable and mobile technologies providing personalised experiences,mediating our engagement with the built environment.The "theatre of the everyday" is now a data rich environment for interaction and today's intuitive communications services are shaping social relations from the interpersonal to the global.As a consequence of this dramatic reformulation of social,spatial and technological relations,in 2017 The Bartlett School of Architecture,at University College London (UCL) launched Design for Performance and Interaction (DfPI),a Master's in architecture programme to critically engage these accelerating transformations.The disruption of emerging technologies are explored through the programme's central tenet that the creation of spaces for performance and the creation of performances within them can be symbiotic design activities.

Computational Entanglements

A classical view of the disciplinary institutions imagines pure and stable branches of knowledge,divided and organised rationally.In practice,disciplines are mutable,historically contingent organisations,growing and shrinking,heterogenous and fractious at times.In a traditional institutional model,when common challenges are found across departments,a multi-disciplinary approach decomposes problems into sub-parts that are addressed by disciplinary expertise.This compartmentalisation can lead to a territorialising of research,and often reinforcing disciplinary traditions rather than challenging them.A historical example of where this hampered progress in research can be found in the multi-disciplinary development of early artificial intelligence(AI) and autonomous robotics.Mechanical,electrical,and computational design challenges were decomposed and dealt with as modular problems independently of one another(Brooks,1999)[1].The incorporation of social sciences such as psychology further siloed study with insufficient dialogue between the humanities and sciences.Phil Agre's critique of early AI research illuminates how disciplinary structures with their own self-reinforcing conceptual schemata had limited the scope for self-critical practices within the emerging field.He describes how "disciplinary culture,runs deeper than we are aware" and can make it "actually impossible to achieve a radical break with the existing methods of the field."(1997)[2]

Disciplines are almost by nature conservative and so in recent decades,inter-disciplinary approaches have become popular to create productive spaces of collaboration.Disciplines to varying degrees can overlap,sharing methods and content and by contrast with the decompartmentalising nature of multi-disciplinary approaches,inter-disciplinary research integrates practices,often motivated by a shared view that existing modes of working are unable or unwilling to tackle emerging challenges.In its basic form,interdisciplinarity allows for a task to be addressed by a novel arrangement of overlapping expertise.A more reflexive,critical interdisciplinarity can also further epistemological concerns,revealing inherent structures (such as self-reinforcing conceptual schemata) and disciplinary relations that uncover potentially productive new areas of research and practice.When roles and boundaries between disciplinary practices become indistinguishable,some practitioners look beyond disciplines entirely for models that reject discrete historical organisations of knowledge.

In the inaugural essay for the Journal of Design and Science,architect and researcher,Neri Oxman argues "that knowledge can no longer be ascribed to,or produced within,disciplinary boundaries,but is entirely entangled"(2016)[3].She points to MIT Media Lab's use of the term "antidisciplinary"to demonstrate its disregard for institutional branches of knowledge,engaging vigorously in complex intertwined subject matter.It is notable that the Media Lab emerged out of MIT's architecture school,incubating collaborations that for the time stretched far beyond architecture's traditional subject matter.Its founder Nicholas Negroponte set out its agenda in a briefing where he described the Media Lab as"designed to be a place where people of dramatically different backgrounds can simultaneously use and invent new media,and where the computer itself is seen as a medium -part of a communications network of people and machines -not just an object in front of which one sits." (Rowan,2012)[4].This was not a new idea however.Decade's before the founding of the Media Lab,the notion of the computer as media has been enticing artists seeking novel forms of expression.Early examples include the exhibitions Cybernetic Serendipity in London in at the Institute of Contemporary Art in 1968,and the presentation of computer generated graphical works by Frieder Nake,Georg Nees,and Herbert Franke at the 1970 Venice Art Biennale.

The emergence of media arts in the context of a discussion of disciplinarity is important,as it represents the clearest example in the arts,of explicit transdisciplinarity.Widening computational literacy,enabled by networked and open source communities has driven the development of interoperable tools that blend previously distinct practices of sound and music production,illustration and graphics,movement and performance,biology and robotics,installation and architectural design.This computational fluidity has the effect of dissolving disciplinary boundaries,and developing not only hybrid forms of existing practices,but also the emergence of radically new forms of practice.This is the distinction I make between interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity.

Foundations of a Transdisciplinary Programme

The formulation of DfPI began with establishing a working group consisting of key Bartlett staff working in performance,media and spatial practices[5].In parallel we turned to London's leading studios specialising in performance and interaction who exemplify transdisciplinary practices rooted in architectural methodologies.These included Umbrellium,Bompas and Parr,Scanlab Projects,Stufish,and Jason Bruges Studio.Principle aims and requirements were mapped out including the need for space to fabricate,test and perform interactive installations and performances.The typically compact central London studio environments of UCL's Bloomsbury campus were unsuitable and so the Faculty took the opportunity to add to its estate by becoming a resident of Here East,the former media complex of the 2012 London Olympics that had been regenerated after the games to provide over a million square feet of versatile spaces for creative and technology companies and institutions.Adjacent to the facility is Hackney Wick,the densest concentration of artist studios in Europe.This diverse ecosystem of creativity and technology were ideal conditions for The Bartlett to partner with UCL's Faculty of Engineering Science to take up residency at Here East and develop new educational programmes and research to benefit from this context.

Inline with the central tenet of DfPI -that the creation of spaces for performance and the creation of performances within them can be symbiotic design activities -we took an active role in not only designing the course but also the facility it would take place within. Core facilities include a large scale 'Black Box' Studio with theatre lighting and a dance floor,a 12 Channel Surround Sound Chamber,'Artifical Sky'Lighting Studio,a Virtual and Augmented Reality Studio with high performance GPU Computing,and a 330-seat multifunctional auditorium (Fig.1).All researchers and programmes at the facility share access to a state-of-the-art digital fabrication facility including CNC manufacturing equipment and industrial robotics.All of UCL's robotics research,that previously occurred in pockets around campus were housed at the spacious new site allowing The Bartlett and Faculty of Engineering Science to share its large-volume robotics for manufacture,inspection and testing,alongside Computer Sciences current research in autonomous multi-agent mobile robotics and surgical robotics(Fig.2).Such a facility is unique in the UK,and with few international equivalents making it an exceptionally fertile environment for the establishing of a transdisciplinary programme.

Conclusions

It is beyond the scope of this article to chronicle the wide diversity of student and staff projects that have emerged from the first 5 years of the masters programme.These are documented at www.interactivearchitecture.org where there is detailed information on the work,and the theoretical discourses that have emerged though this unique experiment in transdisciplinary pedagogy[6].

The UK has historically maintained a rigidly vertical model to architectural education defined by professional accreditation.However we are beginning to see bifurcation of specialist programmes,particularly at postgraduate level,that one could compare to the carving up of medicine at the turn of the 20th into distinct areas of expertise.Architecture has historically held a holistic identity between the arts and engineering but it seems quite certain that as the complexity of designing and constructing the built environment increases,the calls for specialisation will only grow stronger.Our programme does not follow that call but rather resists the strategy of compartmentalisation,instead reaching beyond the discipline to expand what architecture can be as a creative practice.

Literacy in coding,electronic sensing and robotic actuation,animation,digital simulation and fabrication techniques empowers students to realise physical and virtual prototypes that are tested in public settings including the Tate Britain Gallery,The Barbican Centre and Ars Electronica Festival.These material and situated engagements with emerging technologies encourage critical reflection on the ideologies,hidden assumptions and values shaping technological design.This practice of material and critical engagement we believe provides a means for navigating the todays complex cultural,technological and socio-economic landscape.

7 互动技术在建筑中的应用 I 李力

互动概念源于人机互动技术(Human-Computer Interaction Techniques,HCI),通过丰富的输入输出设备来加强人与计算机之间的信息交互方式。近些年信息技术发展,丰富了数字化感知的途径,在数据种类、数据颗粒度及数据处理性能上都有了极大的提升,拓展了互动技术的应用场景

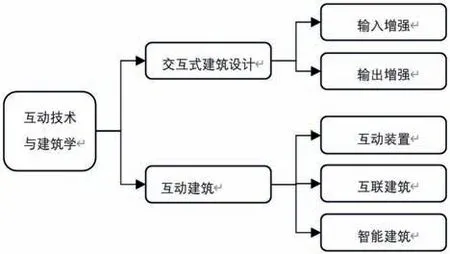

根据现有实践和研究,互动在建筑领域应用根据作用对象的不同,可分为交互式建筑设计(Interactive Architectural Design)和互动建筑(Interactive Architecture)两大类。交互式建筑设计作用于建筑设计过程中,而互动建筑则着眼于如何将互动技术应用于建成环境之中(图 1)。

图1 物理计算在建筑中的应用方式

交互式建筑设计过程

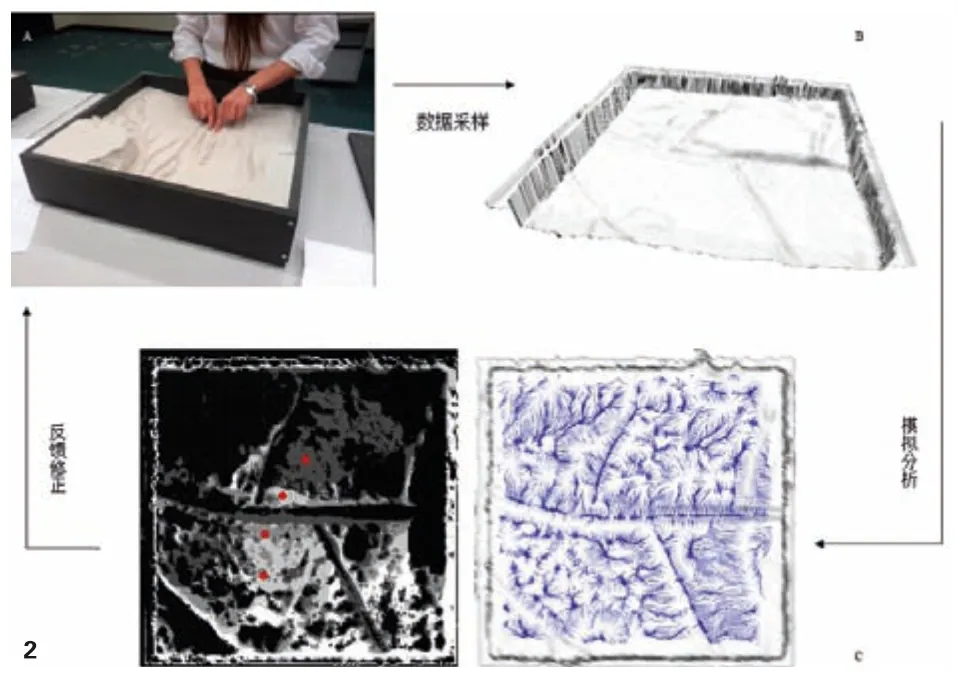

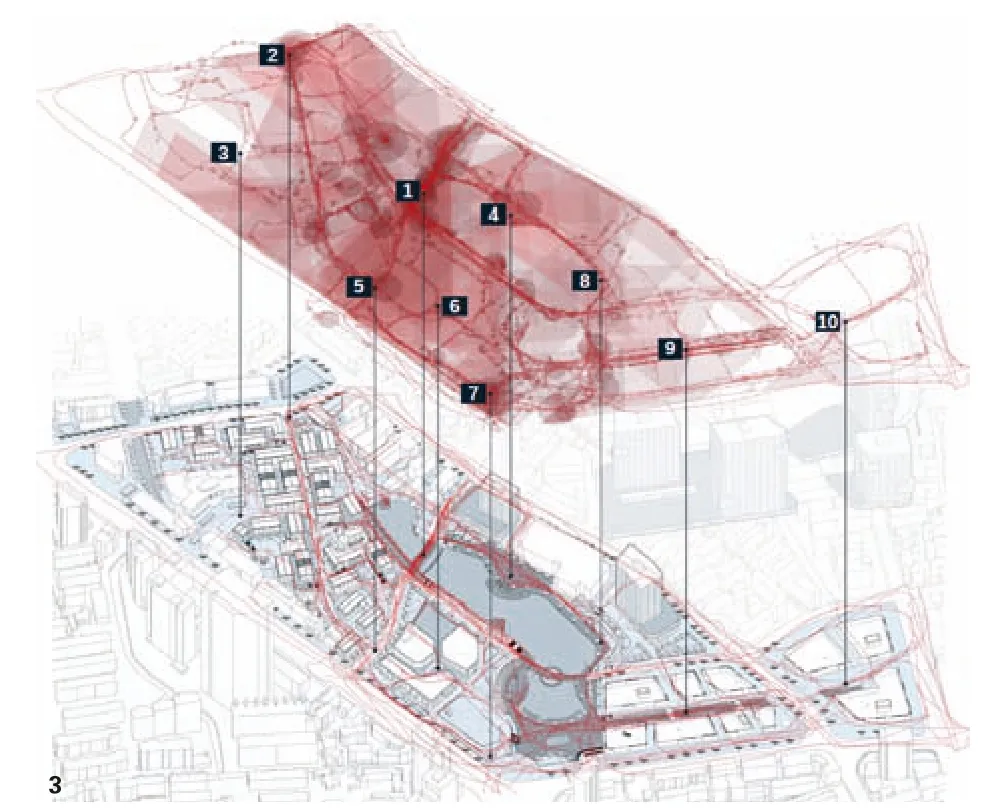

桌面电脑时代,人只能通过鼠标、键盘、显示器与计算机发生交互,表达和感知都受到限制。建筑计算机制图从二维CAD 绘图到三维建模,都受到桌面电脑的限制。近年在输入和输出端出现的越来越多的人机交互设备正在逐渐突破这些限制。例如,有Leap Motion、MYO、Gest 等手势输入设备;如Kinect、激光定位系统等动作捕捉设备;乃至用于脑波监测的便携式EEG 设备,这些对于计算机输入端的增强,使得人能以更直觉的方式进行表达。如ETH 的Landscape Architecture 的Digital Terrain Modelling 课程(图 2),学生在沙盘上对地形进行修改(A),通过双摄像头采集获取三维模型的高程信息,并转换成三维模型(B)。在数字三维模型上使用仿真模拟程序进行可视度、坡度、汇水等分析,分析结果实时反馈给学生,学生根据分析结果进一步修正自己的设计(C)。在计算机输出端,已消费产品化了的虚拟现实(Virtual Reality,VR)和增强现实(Augmented Reality,AR)眼镜等产品,使得参与设计者能以更身临其境的方式体验设计方案。如东南大学五年级公众参与城市设计课程项目,在VR 环境中开发了一套漫游行为监测系统,对被试者在设计方案的虚拟环境中的行进路线、视线停留、主观评价等数据进行实时统计分析,检测设计意图是否被有效落实(图 3)。

图2 Digital Terrain modelling 课程设计流程

图3 VR 环境中采集的漫游及视线数据

互动建筑

互动建筑指直接将互动技术应用于建成环境中。互动设计中有个由人、传感器、控制器、执行器构成的经典闭环。对应到建筑领域,除了人的活动以外,还包括建筑内、外的物理环境,涉及的传感器包括温度、湿度、照度传感器,门、窗及各种建筑设备状态传感器,定位系统等。执行器包括能调节物理环境的建筑设备,例如暖通空调系统、灯光系统、遮阳通风系统、媒体系统等。控制器可以是集中式的或是分布式的。集中式控制可以综合分析环境状况,控制多个执行器切换不同场景模式。分布式控制可利用小型的闭环做出快速灵活的局部响应。根据使用技术和设计侧重点的不同,在此可进一步分为以下几类:互动装置、互联建筑、智能建筑。

互动装置

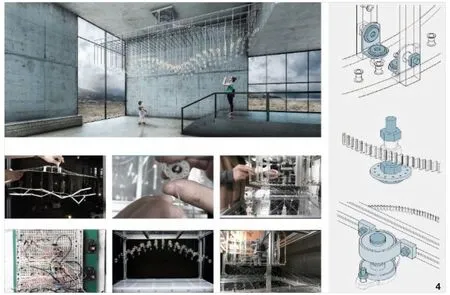

互动装置(Interactive Installation)指通过赋予建筑构件、元素以互动的功能来提供新的服务,营造新的空间体验,或提高建筑性能。在建筑表皮、空间、结构、媒体中都有应用的案例[1]。例如,东南大学互动课程设计作品“弦下”(图4)通过感知人员分布来实时调节高大空间中的吊顶高度。“互动座椅”项目,通过在座椅中植入无线通信芯片,使之相互之间可以通过内部光影及振动来反应传递使用信息,活跃气氛,打破公共空间中冷漠的人际关系(图 5)。

图4 东南大学建筑学院本科四年级互动设计课程学生作业“弦下”

图5 东南大学建筑学院本科四年级互动设计课程学生作业“互动座椅”

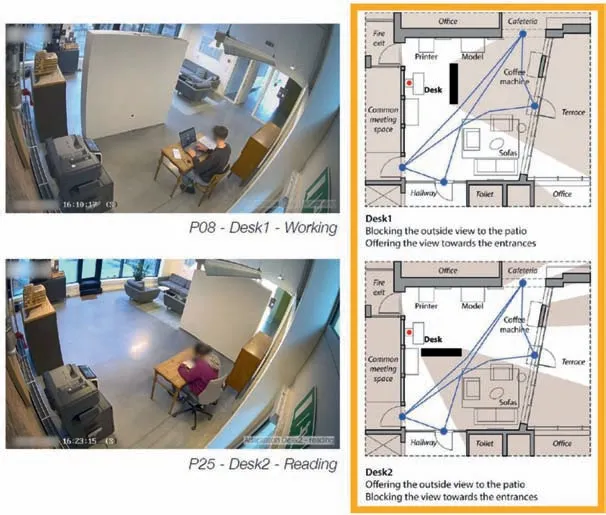

互联建筑

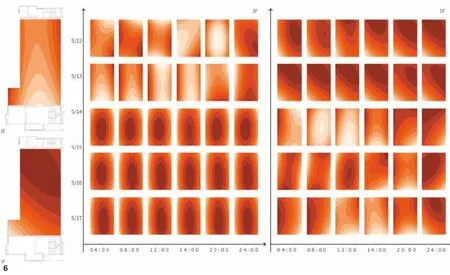

互联建筑(Connected Building)是指将建筑内的电子电器设备及传感器相互连接实现数据的互通。基于WiFi、BLE、Zigbee 的无线传感网络技术的出现,使得智能设备可以不依赖有线网络基础设施,随时被加入和移除网络,并且可以通过网关接入互联网,实现远程监控。传感器体积和成本的降低,可以更高颗粒度和精度来对室内空间环境进行认知,如对于图书馆空间环境行为的研究,通过高密度的传感器分布,可以发现单一大空间中环境行为不均匀分布,从而进行更精细化的调控(图 6)。

图6 由无线传感网络采集的室内空间温度分布数据可视化

智能建筑

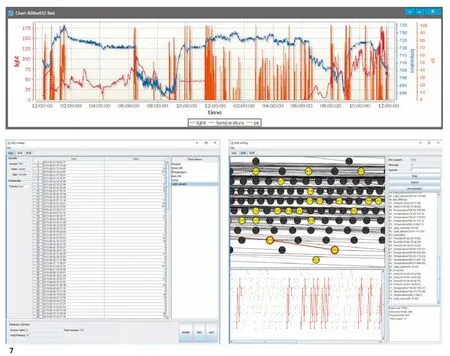

智能建筑(Smart Building)领域的互动技术应用旨在进一步提高建筑的智能化程度。随着嵌入式处理器及云计算技术在算力上的提升。计算单元可以处理更为复杂的任务,尤其是机器学习相关算法的运算,从而实现模式识别和模式挖掘,让控制器从简单的模式切换,转变为可以根据行为模式特征及需求变化进行实时策略调整的智能化调控。如室内行为研究中通过序列模式挖掘算法,对行为中的频繁序列模式进行提取(图 7)。通过深度自编码神经网络对于行为轨迹进行相似度分析等(图 8)。

图7 室内数据序列模式挖掘可视化界面

图8 室内轨迹相似度分析

展望

计算机和建筑相互融合的技术难度正在逐步降低。从建筑设计的角度出发,这些数字电器设备不应该再被视作建筑的附属物,而应当做是一种新的数字建材(Digitalized Materials)。Mikael Wiberg 将其称为互动材质(Interactive Texture),即以物质化地形式呈现,并具有传递信息与互动能力的材料[2]。在信息化和智能时代,建筑不仅提供空间场所,也不仅是柯布西耶所谓的机械美学机器,而应是一个与人互动的居住服务提供者。路易斯·沙里文曾说“形式追随功能”,那么在新的功能定位下,也应产生相匹配的新的建筑形式,而不是形式与技术之间的割裂。在“诗意地栖居”环境背后,是高速交互的数据、信息和运算,也就是Mark Weiser所指的平静技术(Calm Technology)[3]。

8 迈向系统化和情感化的人屋交互设计 I 刘洁

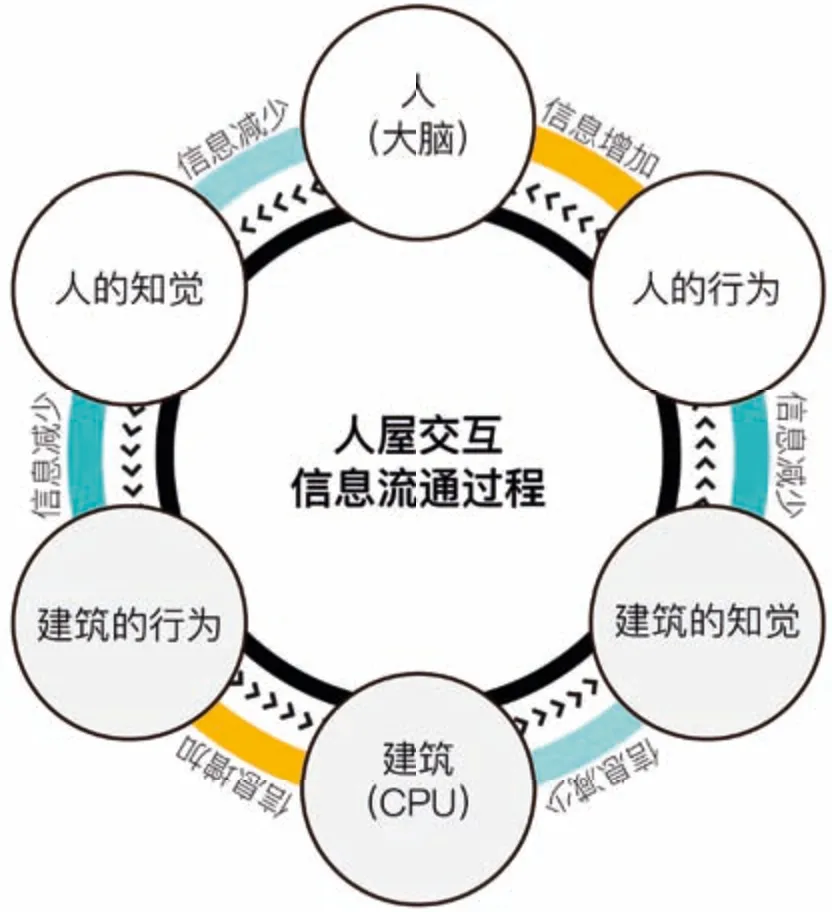

“人屋交互(Human-Architecture Interaction)”这个概念在建筑学领域内属于一个新兴名词,它指的是人和建筑之间的信息交换过程。这里的“屋”特指的是带有计算机和机器特点的可以感知、处理、反馈信息的建筑。人屋交互设计可以看作是“人机交互(Human-Computer Interaction)”与建筑设计的融合,其主要是设计人与建筑之间交互的信息内容和信息形式,包括人和建筑之间应该交流什么信息,以哪种形式来进行交流,怎么样交流才能让信息可达的效率更高,以及如何促进信息交流的行为产生和延续[1](图 1)。

图1 人屋交互中的信息流通过程(注:作者绘制)

人屋交互设计的概念变迁

虽然人和建筑之间交互的概念可以追溯到20 世纪60 年代英国建筑师塞德里克·普莱斯(Cedric Price)的“欢乐宫(Fun Palace)”设计[2],但是“人屋交互设计”这个概念的明确和建构却是近十余年的事情。不同于交互建筑对于空间的强调,人屋交互设计更强调对信息的思考。人屋交互设计一开始被明确提出是从提升建筑性能角度出发的,南加州大学的法罗赫·贾齐扎德(Farrokh Jazizadeh)等人提出通过增加“人屋交互设计(Human-Building Interaction Design)”的方式来帮助房间使用者平衡房间关环境舒适度和照明能耗的关系[3]。后来,“人屋交互设计”的概念变得更为具体。瑞士弗雷堡大学的哈米德·阿拉维(Hamed S.Alavi)提出“人屋交互设计”主要研究和设计的是空间中的人以一种交互的模式塑造建筑的实体构成、空间组织及内部社会活动的可能性[4]。阿拉维借鉴了比尔·希利尔(Bill Hillier)在《空间是机器》一书中提到的建筑概念,将交互的客体从建筑物实体本身转向为由建筑外表皮包裹的整个建筑及内部的活动[5]。这其实是把人屋交互设计的研究范畴从建筑设备自动化的角度拓展到了建筑设计的视角。但是这个时候的“屋”还是“building”的概念。后来,随着虚拟现实、增强现实、混合现实技术的增强,研究领域对于人屋交互的研究又进一步扩展到了虚拟的建筑空间。但这个时候也出现了概念定义模糊,建筑与建筑的附属物(装饰、设备等)、建筑的孪生体(建筑模型等)都成为了“屋”的一部分。与此同时,“屋”究竟是“building”还是“architecture”也成为了讨论的另一个问题。考虑到在建筑学的理论范畴中,人屋交互并非只是寻求一种如机器般功能型的一种交互,而更希望能够构建一种美感的、诗意的交互形式,因此,“人屋交互设计”便进一步定义为了“Human-Architecture Interaction Design”。

人屋交互设计的发展趋势

人屋交互设计目前仅仅是处在一个萌芽阶段,诸多学者的普遍共识是人屋交互设计的发展是为了提高建筑的适应性水平,让建筑可以能够自主地与空间者交流,并根据空间者的需求来改变空间的状态。目前该领域的设计研究还是以技术应用为主要方向,以实现建筑从静态信息输出者到动态的、个性化的信息输出者的转变。然而建筑作为科技和艺术的结合,人们对它的需求并非单纯的是一种功能需求,而是一种个性化的、联结感的、美观得体的空间氛围状态或者说场所精神的需求[6]。因此,在这个背景下,我们需要站在更高的维度来思考建筑设计,思考交互设计,并从信息的维度重新思考建筑的本质和相关概念,进而将建筑设计从空间设计演变成一种“氛围场”的设计。要达到这个状态,人屋交互设计需要向系统化和情感化两个维度进一步发展。

人屋交互设计的系统化发展是为了提高建筑的智商,它包括空间的系统化和信息的系统化。空间的系统化要求我们重新审视建筑各个构件的存在意义和可能形式。如果窗的存在是为了通风采光,那么不需要通风采光的时候窗是否还有存在的意义?如果门的存在是为了通行,那么无人通行的时候,门与墙之间的区别是什么?正如海德格尔关于“存在”的理论,认为只有有人使用的空间才具有“存在”的意义,那么建筑的空间以及各种构件只需要在人需要的时候再出现。这时,空间的各个组成部分将会变得一体化和系统化,并处于一种动态变化的过程中。墙壁在人需要采光通风、视线通达的时候裂开孔洞变成窗户,地面在人需要办公或休息的时候升起变成家具。信息的系统化要求人屋交互设计跳出单点化、片段化的空间设计模式,将建筑看做整个社会信息系统的一个终端来思考人和建筑之间可以交换信息内容及形式。建筑与社会中的各种信息终端之间可以信息共享,并实现交互逻辑的自我更新、升级和进化,进而构建一种城市、建筑、家具、产品一体化的信息系统服务形态。

人屋交互设计的情感化发展是为了提高建筑的情商,它包括场所的情感联结和空间的情绪调节。场所的情感联结是诺伯格·舒尔茨的“场所精神”中经常提到的概念[7]。人对于空间的认知建立在相似环境记忆之上,比如空间中的某个形态让人联想到了山峰,某种味道让人联想到了儿时的环境。这种信息的匹配让空间与人之间形成了情感联结。正如认知心理学家唐纳德·诺曼(Donald Norman)所强调的设计“……实际上是在设计使用者的情绪感受……”[8],未来的人屋交互交互设计可以根据每个人的体验经历来个性化地调整空间中的相关信息,从而可以打通空间和人之间的情感联结通道,提升人的情绪体验感受。空间的情绪调节则是需要思考该如何充分利用空间中的各种信息来为人们提供更有利于人的心理健康的空间环境状态。人的情绪是波动的、变化的。尤其是随着社会压力的增加,越来越多人受到负面情绪的困扰[9]。未来的人屋交互设计需要将情绪调节作为设计重点,实时感知使用者的情绪,并循序渐进地改变空间的形状、色彩、气味、肌理等信息,进而提供给人因人而异的、随着情绪缓慢变化的空间氛围,以促进积极情绪的产生,减缓消极情绪的合成。

这时候,我们也需要借助认知科学的知识,通过用户实验等科学手段,更科学地来探讨人屋交互设计的设计方法的有效性、空间的丰富度和合理性,以创造一种更为宜居的人因环境。