161例脑出血患者脑微出血情况调查

祁学章, 梅炳银, 徐俊峰, 王 娜, 舒志刚

(湖北省鄂州市中心医院, 1. 老年病科; 2. 神经内科, 湖北 鄂州, 436000)

161例脑出血患者脑微出血情况调查

祁学章1, 梅炳银2, 徐俊峰2, 王 娜2, 舒志刚2

(湖北省鄂州市中心医院, 1. 老年病科; 2. 神经内科, 湖北 鄂州, 436000)

目的 探讨脑出血患者发生脑微出血(CMBs)的相关危险因素。方法 采用1.5T磁共振观察161例脑出血幸存者。根据脑出血的部位进行分组分析(58例脑叶出血, 103例非脑叶出血)。结果 88例患者(55%)在脑出血开始时就发现脑微出血(CMBs), 76例患者(47%)在随访中发现脑微出血(CMBs)。可以作为预测因子的包括在脑出血开始时发现≥1个脑微出血、陈旧性脑出血。根据脑出血部位分组,非脑叶出血组患者的脑微出血与腔隙状态、应用抗血小板药物相关。在脑叶出血患者组中,脑微出血与影像学显示的较大脑出血相关。结论 CMBs的预后和相关因素根据出血部位的不同而有差异。

抗血小板药物; 脑出血; 脑微出血; 危险因素

自发性脑出血患者中,脑微出血(CMBs)非常常见[1]。在脑出血和缺血性卒中幸存者中,CMBs的存在和数量是再发出血的一项高危因素[2-4]。一组对1 460例脑出血患者的回顾性分析[5]显示,应用华法林的患者的CMBs几乎是未用任何抗栓药患者的2倍。这导致人们形成一种认识,把CMBs作为易发出血性脑血管病的生物学标志[6], 并避免在这类患者中应用抗栓药[7]。但CMBs是否真的增加抗栓药相关脑出血并没有得到肯定的结论。本文根据脑出血患者的出血部位进行分组,进行长时间的跟踪随访,探讨伴有CMBs的脑出血患者的预后相关因素,现报告如下。

1 资料与方法

1.1 一般资料

选取本院神经内科2009年7月—2015年12月收治的确诊脑出血患者,入选标准符合2007年《中国脑血管病防治指南》第1版脑出血诊断标准。排除单纯脑室出血、出血转化和先天血液病、创伤性、肿瘤、血管畸形所致脑出血。纳入标准:患者脑出血后存活6个月以上; 至少间隔6个月的2次MRI检查结果。同时收集患者的相关的统计学数据,包括公认的血管病危险因素(高血压、糖尿病、吸烟、嗜酒、房颤)和既往疾病史(脑缺血,短暂性脑缺血发作、脑出血、心肌缺血和痴呆),并且记录抗栓药的应用(抗血小板聚集药物、口服抗凝药)。计划性地随访所有患者(发病6个月时1次,以后每年1次),每次随访记录抗栓药的应用,降压药的应用和他汀类药物的应用。测量血压、行头部MRI检查。

1.2 影像学分析

所有MRI结果由本科2位神经病学专业医生独立阅片并记录结果。根据脑出血后第1次MRI照片(照片时间的中位数 7 d, IQR 4~14 d)开始记录数据,直到记录的最后的一次随访(中位数 3.4年, IQR 1.4~4.7年)。在每一次时间点,用同一个MRI设置相同参数拍照(西门子1.5T磁共振,TR 49 ms, TE 40 ms, 层厚2 mm, 反转角15°, 视野230 mm, 层间距0.4 mm)。

记录每一张磁共振片的脑出血部位,分为: ① 脑叶出血,包括大脑半球边缘至深部灰质结构。② 非脑叶出血,包括豆状核、尾状核、丘脑、内囊、外囊、脑干和小脑。③ 不能分类的脑出血。④ 多发脑出血。运用4分法评价脑皮质萎缩(GCA), 运用Fazekas 量表[8]评价脑白质病变(WMH, 0~3分)。腔隙主要用来描述腔隙性脑梗死,或深部的、皮质下的或脑桥的、类似脑脊液样信号的卵圆形的损伤病灶(3~15 mm), 伴或不伴液体衰减反转恢复成像序列高信号(排除血管周围间隙)。CMBs的定义为在磁敏感加权成像上(SWI)表现为直径≤10 mm的圆形或椭圆形低信号灶[9]。位置确定为脑叶(包括皮质、灰白质交界区皮质下白质),非脑叶区(神经节、内囊区和后窝),混合区(脑叶和非脑叶病变同时存在)。

1.3 统计学分析

比较2组的基线数据,运用χ2检验分析分类变量。对与CMBs相关的数据进行变量回归分析,然后调整年龄、性别和间隔时间。根据脑出血的部位分析(脑叶和非脑叶出血)。运用SPSS 22.0进行统计分析。

2 结 果

161例患者中(年龄中位数 64岁, IQR 53~76), 88例患者至少有1个CMBs( IQR 1.5~12.5), 其中18个(20%)是脑叶微出血。24个(28%)是非脑叶微出血。46个(52%)是混合型微出血。2组解剖上的分布和数量在脑叶出血和非脑叶出血是相近的,见表1。2组患者神经功能缺损的严重程度相近。

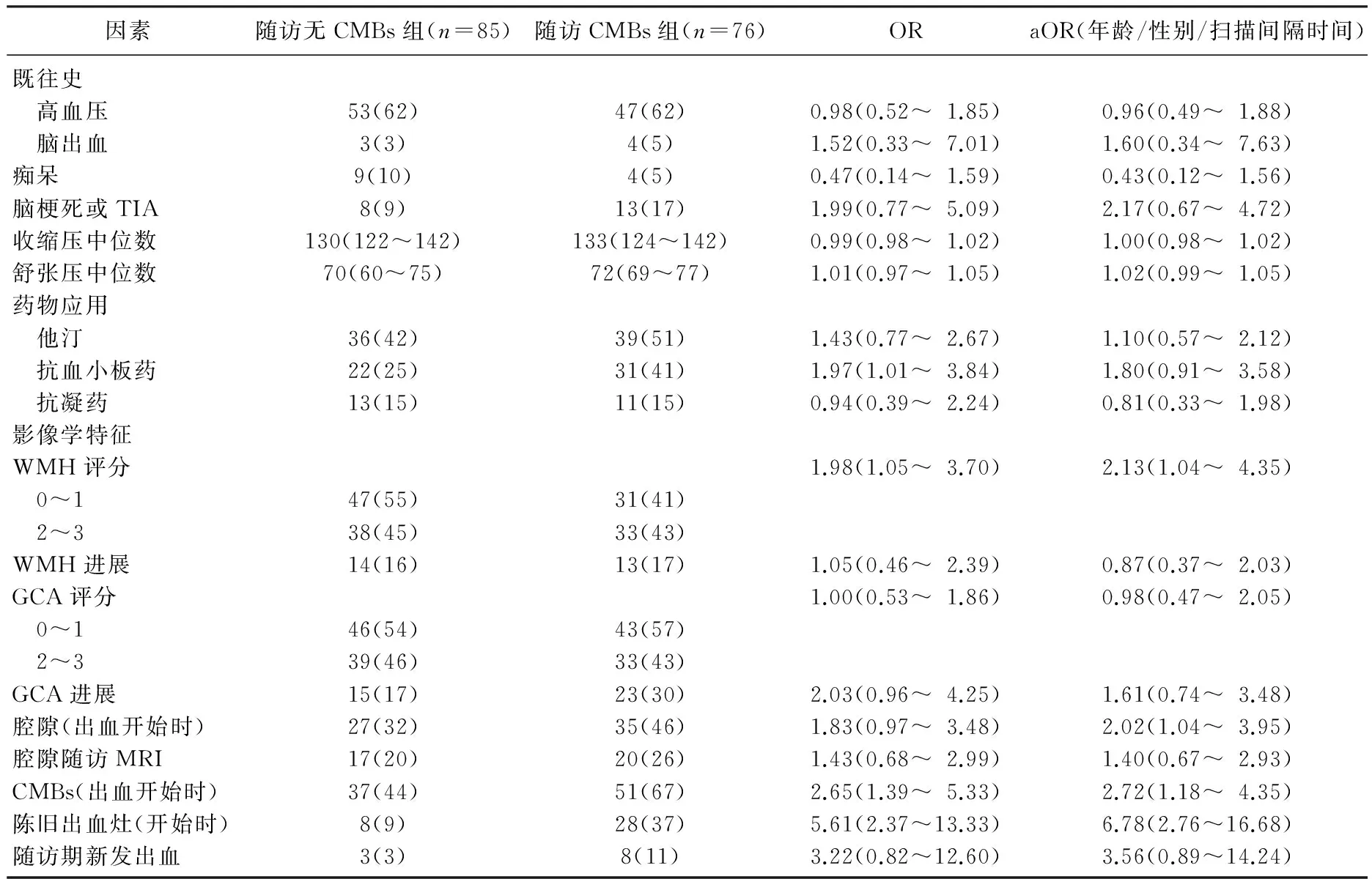

表1 脑出血患者CMBs的相关因素

有76人(47%, 95%CI 40%~55%)在随访期间的3.4(IQR 1.4~4.7)年间出现了CMBs, 包括25例在脑出血刚发作时没有微出血的患者,一共285个新发CMBs, 相当于每100人每年发作13.2个CMBs。脑叶出血患者中(n=58), 26例(45%, 95%CI 32~58)发生了CMBs, 其中8例(31%, 95%CI 12~50)发生在脑叶。11例(42%, 95%CI 22~63)为非脑叶CMBs。7例(27%, 95%CI 9~45)CMBs位于混合位置。非脑叶出血(n=103)患者中, 50例(48%, 95%CI 39~58)发生了CMBs, 其中10(20%, 95%CI 8~31)例发生在脑叶。24例(48%, 95%CI 34~62)为非脑叶CMBs。16例(32%, 95%CI 19~45)CMBs位于混合位置。

脑出血发作时,有CMBs较无CMBs患者随后发作脑CMBs的危险性高2.5倍(aOR=2.72, 95%CI 1.18~4.35), 这在多发CMBs的患者中尤为突出。在混合区域(aOR=3.73, 95%CI 1.67~8.31)和脑出血发作时就有陈旧性脑出血病灶患者中(aOR=6.78, 95%CI 2.76~16.68)发生CMBs较多。虽然在二变量回归分析中发现脑出血后应用抗血小板药和CMBs相关(OR=1.97, 95%CI 1.01~3.84), 但是在对年龄、性别和随访时间等干扰调整后,无显著性差异(aOR=1.80, 95%CI 0.91~3.58)。

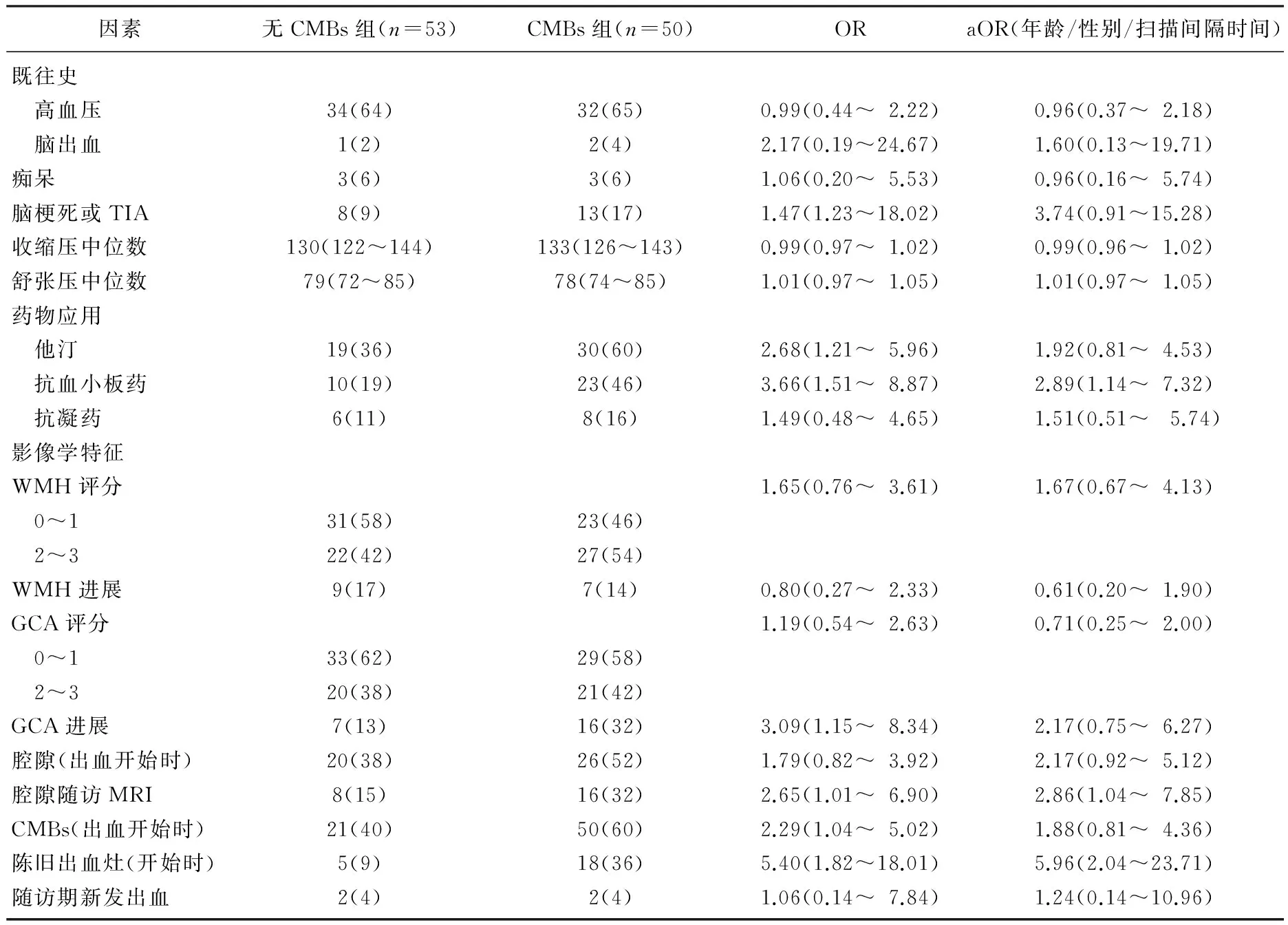

当把患者根据出血部位分组时,脑叶出血和非脑叶出血有显著差异,见表2、3。非脑叶出血患者服用抗血小板药的影响具有显著差异(aOR=2.89, 95%CI 1.14~7.32), 但是这种差异在脑叶出血患者中没有出现(aOR=0.69, 95%CI 0.21~2.12)。2组中服用抗血小板药的比例是相近的(35%∶32%,P>0.05)。非脑叶出血患者, CMBs和新的腔隙形成有关(aOR=2.86, 95%CI 1.04~7.85), 脑叶出血患者中, CMBs与新的脑叶出血相关(aOR=9.76, 95%CI 1.07~88.77)。

表2 103例非脑叶出血患者CMBs相关因素

3 讨 论

在卒中患者中,脑出血患者的CMBs发生率为19%~83%, 高于脑梗死患者的15%~35%[10]。通过对本组脑出血患者的长期观察,作者发现47%(95%置信区间40~55)患者在后期的随访中发生了CMBs。在非脑叶出血患者中, CMBs与腔隙相关(aOR=2.86, 95%CI 1.04~7.85), 与其后应用抗血小板药物相关(aOR=2.89, 95%CI 1.14~7.32), 在脑叶出血患者中, CMBs与既往出血相关(aOR=9.76, 95%CI 1.07~88.77)。

表3 58例脑叶出血患者CMBs相关因素

CMBs在普通人群中的发生率从4年发生CMBs 6.9%[11], 到3年发生10%都有报道[12], 12%也有报道(随访年限中位数 1.9年)[13]。本研究的脑出血幸存者中,随后的3.4年里发生新的CMBs达47%, 远高于腔隙性脑梗死后2年随访发生CMBs的18%[14], 脑出血后CMBs的高发病率可能反映了在脑出血患者中存在许多小血管病患者。一项人数较少的初发脑出血患者报道[15-16]CMBs发生率30%~50%。在缺血性卒中患者中,高血压被认为是CMBs的危险因素[17]。

在脑出血开始时就存在CMBs和陈旧出血灶,预示后期会出现CMBs, 这在既往的试验中已经得到了证实[18]。但根据出血部位的不同,预后和相联系的因素也不同,这提示了可能存在未能检查出的血管病,在脑叶出血患者中, CMBs和新的脑出血相联系,这在以前已经得到证实,这提示在脑叶出血患者中CMBs是易发作出血的血管病的标志,这需要引起警惕。脑叶和皮质一皮质下CMBs患者多为载脂蛋白E(ApoE)82和£4等位基因携带者[19], 病理学改变为脑血管淀粉样变性。在非脑叶出血的患者中, CMBs与腔隙相联系,提示缺血和出血的可能性都增加。作者发现抗血小板药物的应用和CMBs是相关的,在非脑叶出血中尤其显著,推测CMBs可能反映与抗血小板药物相关的未知的小血管病的进展。

总之,在脑出血后经常出现CMBs, CMBs的预后和相关因素根据出血部位的不同而有差异,尽管在脑叶出血患者中CMBs是易发出血的生物学标记,在非脑叶出血的患者中, CMBs的进展的意义并非绝对,因为缺血的风险也在增加,因此CMBs可以作为一个替代的生物学标记。

[1] Cordonnier C, Al-Shahi Salman R, Wardlaw J. Spontaneous brain microbleeds: systematic review, subgroup analyses and standards for study design and reporting[J]. Brain, 2007, 130(pt 8): 1988-2003.

[2] Greenberg S M, Eng J A, Ning M, et al. Hemorrhage burden predicts recurrent intracerebral hemorrhage after lobar hemorrhage[J]. Stroke, 2004, 35: 1415-1420.

[3] Jeon S B, Kang D W, Cho A H, et al. Initial microbleeds at MR imaging can predict recurrent intracerebral hemorrhage[J]. J Neurol, 2007, 254: 508-512.

[4] Fan Y H, Zhang L, Lam W W, et al. Cerebral microbleeds as a risk factor for subsequent intracerebral hemorrhages among patients with acute ischemic stroke[J]. Stroke, 2003, 34: 2459-2462.

[5] Lovelock C E, Cordonnier C, Naka H, et al. Edinburgh Stroke Study Group. Antithrombotic drug use, cerebral microbleeds, and intracerebral hemorrhage: a systematic review of published and unpublished studies[J]. Stroke, 2010, 41: 1222-1228.

[6] Greenberg S M, Vernooij M W, Cordonnier C, et al. Microbleed Study Group. Cerebral microbleeds: a guide to detection and interpretation[J]. Lancet Neurol, 2009, 8: 165-174.

[7] Brown M M. Identification and management of difficult stroke and TIA syndromes[J]. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2001, 70(suppl 1): I17-I22.

[8] Fazekas F, Chawluk J B, Alavi A, et al. M R signal abnormalities at 1. 5 T in Alzheimer’s dementia and normal aging[J]. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 1987, 149: 351-356.

[9] Cordonnier C, Potter G M, Jackson C A, et al. Improving interrater agreement about brain microbleeds: development of the Brain Observer MicroBleed Scale (BOMBS) [J]. Stroke, 2009, 40: 94-99.

[10] Santhosh K, Kesavadas C, Thomas B, et al. Susceptibility weighted imaging: a new tool in magnetic resonance imaging of stroke [J]. J Clin Radio, 2009, 64: 74-83.

[11] Akoudad S, Darweesh S K, Leening M J, et al. Use of coumarin anticoagulants and cerebral microbleeds in the general population[J]. Stroke, 2014, 45: 3436-3439.

[12] Poels M M, Ikram M A, van der Lugt A, et al. Incidence of cerebral microbleeds in the general population: the Rotterdam Scan Study[J]. Stroke, 2011, 42: 656-661.

[13] Goos J D, Henneman W J, Sluimer J D, et al. Incidence of cerebral microbleeds: a longitudinal study in a memory clinic population[J]. Neurology, 2010, 74: 1954-1960.

[14] P Klarenbeek, R J van Oostenbrugge, R P Rouhl, et al. Higher ambulatory blood pressure relates to new cerebral microbleeds: 2-year follow-up study in lacunar stroke patients[J]. Stroke, 2013, 44: 978-983.

[15] Chen Y W, Gurol M E, Rosand J, et al. Progression of white matter lesions and hemorrhages in cerebral amyloid angiopathy[J]. Neurology, 2006, 67: 83-87.

[16] Mackey J, Wing J J, Norato G, et al. High rate of microbleed formation following primary intracerebral hemorrhage[J]. Int J Stroke, 2015, 10: 1187-1191.

[17] Gregoire S M, Brown M M, Kallis C, et al. MRI detection of new microbleeds in patients with ischemic stroke: fiveyear cohort follow-up study[J]. Stroke, 2010, 41: 184-186.

[18] van Dooren M, Staals J, de Leeuw P W, et al. Progression of brain microbleeds in essential hypertensive patients: a 2-year follow-up study[J]. Am J Hypertens, 2014, 27: 1045-1051.

[19] Kim M, Bae H J, Lee J, et al. APOE 2/4 polymorphism and cerebral microbleeds on gradient-echo MRI [J]. J Neurology, 2005, 65: 1474-1475.

Investigation on cerebral microbleeds condition of 161 patients with cerebral hemorrhage

QI Xuezhang1, MEI Bingyin2, XU Junfeng2, WANG Na2, SHU Zhigang2

(1.DepartmentofGeriatrics; 2.DepartmetnofNeurology,EzhouCentralHospital,Ezhou,Hubei, 436000)

Objective To explore associated factors of cerebral microbleeds (CMBs) in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). Methods A total of 161 ICH patients were detected by 1.5T magnetic resonance imaging. Patients were divided into different groups according to ICH location (58 cases with lobar ICH, 103 cases with non-lobar ICH). Results Eighty-eight (55%) patients hadCMBs at ICH onset, and 76 (47%) had CMBs during follow-up. Predictors of incident CMBs were ≥1 CMBs at ICH onset and old radiological macrohemorrhage. In the patients with non-lobar hemorrhage, CMBs was associated with lacunar state and antiplatelet drug use. In patients with lobar hemorrhage, CMBs was associated with large brain hemorrhage showed by imaging display. Conclusion The prognosis and related factors of CMBs are different according to the location of hemorrhage.

anti-platelet agents; intra-cerebral hemorrhage; cerebral microbleeds; risk factors

2016-12-20

梅炳银,E-mail:94393801@qq.com

R 743.34

A

1672-2353(2017)07-016-05

10.7619/jcmp.201707005