血脂紊乱与骨代谢

中南大学湘雅二医院 苏甜 罗湘杭

引 言

人口老龄化已经成为全球关注的问题,伴随而来的是动脉粥样硬化(atherosclorosis,AS)和骨质疏松(osteoporosis,OP)患病率的增加。在过去10年中,不断有研究表明,动脉粥样硬化和骨质疏松有关联[1-4]。在骨质疏松患者中,动脉钙化也很普遍[5],并且动脉钙化的进程和骨量减少的速度是一致的[1,2]。而且,脉搏波传导速率的增加(反映动脉钙化的一个指标[6])与骨密度和跟骨的骨定量超声骨质测量参数呈负相关[7]。这些研究都提示我们,心血管疾病和骨质疏松通过一些共同作用于血管和骨细胞的因素而相互关联。脂肪被公认为是动脉粥样硬化和心血管疾病的危险因素[8]。本文就脂代谢与骨代谢的关系予以综述,旨在为骨质疏松的治疗提供一定的依据。

脂代谢通路与骨代谢通路

脂肪细胞和成骨细胞共同起源于骨髓基质细胞[9]。脂肪细胞和成骨细胞的生理平衡是通过一系列信号通路的调节而实现的。参与这些信号通路的调节因子包括过氧化物酶体增生物激活受体γ2(peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ2,PPARγ2)、核因子κB受体活化因子配体(receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand,RANKL)、核因子κB受体活化因子(receptor activator of nuclear factor κB,RANK)、骨保护素(osteoprotegerin,OPG)、Wnt/β-catenin 信号通路[10]。

PPARγ属于配体依赖性的核受体超家族的成员,它可以调节目标基因的表达[11]。PPARγ基因是决定骨髓多能干细胞向脂肪细胞、成骨细胞或破骨细胞分化的关键转录因子。PPARγ有两种表达形式:PPARγ1,主要表达于巨噬细胞、结肠上皮细胞、内皮细胞以及血管平滑肌细胞;PPARγ2主要表达于脂肪组织,调节脂肪生成[12-14]。脂代谢紊乱可以促使氧化性脂质增加,而增加的氧化性脂质可以激活骨髓PPARγ2,从而抑制成骨细胞和骨形成,促进脂肪细胞的分化[15]。噻唑烷二酮类(thiazolidinediones,TZDs)药物通过与PPARγ结合并激活其通路,从而刺激细胞向脂肪分化并抑制成骨分化[16]。也有一些研究报告,PPARγ可以抑制破骨细胞生成[17-19]。

Wnt蛋白是一类分泌型的富含半胱氨酸的糖基化蛋白,可在多种细胞中表达。Wnt/β-catenin信号通路是调节骨代谢的经典通路。Laudes[20]研究发现,Wnt信号通路中几个Wnt家族成员可以在脂肪形成的早期阶段起到抑制作用,减少人类间充质干细胞分化成前脂肪细胞。相反,Wnt通路的内源性抑制物却会提高脂肪细胞的形成而减少成骨细胞的分化。

OPG是一种可溶性糖蛋白,属于肿瘤坏死因子超家族的成员[21],它可以与RANK结合,从而抑制破骨细胞的生成[22]。Ayina等[23]研究发现,在肥胖女性中,高密度脂蛋白胆固醇(high density lipoproteincholesterol,HDL-C)与OPG呈正相关,低密度脂蛋白胆固醇(low density lipoprotein-cholesterol,LDL-C)与OPG呈负相关。该研究结果与Bennett等[24]的研究结果相一致,在动物研究中,OPG是心血管的保护因素。但是在Ayina等[25]之前的研究中发现,在老年人群中,HDL-C 的浓度与OPG无关联。

脂肪细胞因子与骨代谢

目前已经有许多研究证实,脂肪细胞不仅仅是一个能量储存器官,它同时也可以分泌很多生物活性细胞因子,我们称之为脂肪细胞因子,包括纤溶酶原激活物抑制剂-1、肿瘤坏死因子-α(Tumor Necrosis Factor,TNF-α)、抵抗素、瘦素以及脂联素。本文主要论述瘦素和脂联素。

1. 瘦素

瘦素(Leptin)是由脂肪细胞分泌的蛋白质类激素,主要由白色脂肪组织产生。瘦素作为脂肪组织的保护因素,目前已经被认成为是骨代谢的重要调节因素,但是瘦素对骨代谢的具体作用,各学者的研究结果不一。有文献[26]报道,在编码瘦素基因缺失的小鼠中,其骨形成和骨量是减少的。Thomas等人以及其他学者[27-29]研究报道,成骨细胞系也有瘦素的作用位点。瘦素可以诱导激活丝裂原活化蛋白激酶(mitogen-activated protein kinases,MAPK)通路,该通路的激活可以刺激成骨细胞的分化[30]及PPARγ,而PPARγ可以抑制脂肪生成[31]。而且,在人类成骨细胞培养实验中,瘦素可以通过抑制凋亡的作用而促进成骨细胞的活动[32]。有学者[33]曾报道,瘦素可以抑制RANKL的表达,从而抑制破骨细胞的生成;而且瘦素还可以刺激OPG的表达从而抑制骨吸收,促进骨形成。瘦素也能够促进人类单核细胞分泌白细胞介素-1(interleukin-1,IL-1)[34],而该受体拮抗剂可以减少与IL-1相关的骨转换以及雌激素缺乏引起的骨量丢失。与这些研究结果一致的是,Cornish等[35]的研究也表明,与对应的野生型小鼠相比,瘦素缺乏的ob/ob小鼠,其骨矿物质含量(bone mineral conten,BMC)和骨密度(bone mineral density,BMD)较低[29]。对下丘脑予以瘦素基因治疗后,ob/ob小鼠骨量和骨长度增加[35]。

尽管一些研究者报道,血清瘦素水平与BMD[36-41]或者BMC[42]呈正相关,但是其他学者却未能发现两组之间存在正关联,甚至有些学者发现两者呈负相关[42-45]。Ducy及其同事[48]研究发现,瘦素缺乏的ob/ob小鼠拥有更高的骨量。相反,向下丘脑注射瘦素后,其骨量减少,可能原因是瘦素促进了骨吸收、抑制骨形成。有研究[38,40-42]发现,当校正脂肪质量以后,两者之间的正相关关系就不存在了。

前文已述及瘦素可以增加OPG的生成,减少RANKL的表达,进而抑制破骨细胞的分化,并可以抑制骨髓间充质干细胞(bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells,BMSCs)向脂肪细胞的分化、促进成骨细胞的分化。但是高水平的瘦素却可以导致BMSCs的凋亡[46],同时也可以增加骨吸收、减少骨形成。Hamrick等[47]提出这一假设:脂肪生成增加可以增加骨髓微环境瘦素的浓度,从而导致骨量减少。这也许可以解释为何各学者关于瘦素与BMD关系的研究结果不一,其他的原因还包括种族的差异、研究人群的数量以及统计学方法的差异。

2. 脂联素

脂联素(Adiponectin,ADPN)是脂肪细胞分泌的一种内源性生物活性多肽或蛋白质。脂联素又被称作Acrp30、apM1、AdipoQ、GBP28,在分化的脂肪细胞中高度特异性表达,在血浆中含量丰富[48-50]。脂联素是分子量为30KD的多肽,由氨基末端的分泌信号序列、一段特异序列、一组由22个氨基酸组成的胶原重复序列和一段球状序列组成[48-50]。成熟的脂肪细胞和成骨细胞表达和分泌一些共同的因子,提示我们这些细胞之间存在密切联系[51]。有研究[52]报道,脂联素及其受体也可以在骨形成细胞中表达。这些研究可以表明,脂联素可以将脂肪组织的信号传递到骨组织,但是脂联素对骨代谢的影响,目前意见尚未统一。

在罗湘杭等[53]的研究中发现,脂联素可以促进成骨细胞的增殖和分化。这种增殖应答反应是由AdipoR/JNK信号通路调控,而分化应答反应是由AdipoR/p38 MAPK信号通路调控,这些发现表明人类破骨细胞是脂联素的直接调控靶点。Kazuya Oshima等[54]也认为脂联素可以通过抑制破骨细胞生成、激活成骨细胞生成而增加骨量。

Kajimura等[55]研究认为,根据作用部位和作用方式不同,脂联素具有双向作用:脂联素直接作用于成骨细胞,会抑制成骨细胞的增殖;而在中枢信号通路中,脂联素却会促进成骨细胞的增殖。罗湘杭等[56]在他们的另一研究中指出,脂联素通过促进成骨细胞RANKL的表达,抑制OPG的表达,间接促进破骨细胞的形成。

在脂联素过度表达的小鼠模型中,小鼠的骨量和骨形成增加,远高于野生型小鼠[57]。但是,Ealey等[58]却发现了不一样的结果,跟对照小鼠相比,脂联素过度表达的小鼠其股骨的BMC和股骨颈的峰值负荷能力更低。另外有学者发现,在脂联素编码基因敲除的小鼠模型中,其骨量是增加的[59-62]。

由于脂联素对骨代谢的影响意见尚未统一,还有待进一步研究。

血脂异常与骨质疏松

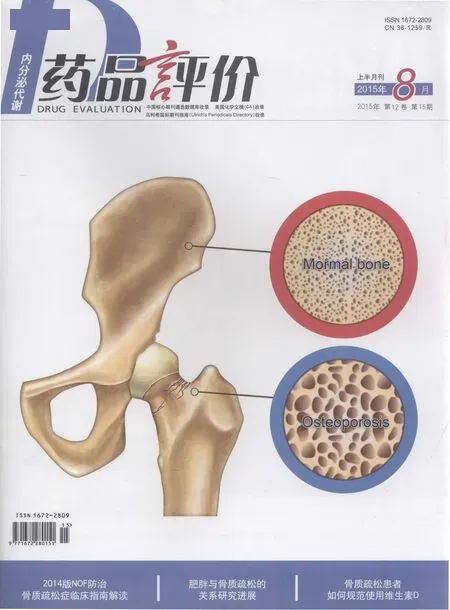

血脂异常指血浆中脂质量和质的异常。OP是一种以骨量降低和骨组织微结构破坏为特征,导致骨脆性增加和易于骨折的的代谢性骨病。骨质疏松症的诊断主要是根据BMD和临床表现。骨质疏松在女性中的发病率要高于男性[63],但是男性骨质疏松性骨折却比女性更为常见[64],而且绝经后女性骨质疏松的发病率要高于绝经前女性[65]。

血脂与BMD之间可能存在联系,最初是因为他汀类药物对BMD有正向作用而被逐渐发现的[66,67]。各类研究都表明,他汀类药物(HMG-CoA还原酶抑制剂)可以增加骨密度,降低骨折发生率[68,69]。在Orozco等[70]的研究中发现,和血脂正常的女性相比,血脂异常的绝经后女性腰椎和股骨骨密度较低,骨量减少的风险增加,提示高脂血症与骨质疏松相关。

之前有关骨密度和血清胆固醇(total cholesterol,TC)之间关系的研究缺乏一致性。有相关报道[71-74]指出骨密度和血清胆固醇之间无密切联系,即血清胆固醇对骨细胞的代谢无显著作用。但是动物实验和临床实验均已证实血清胆固醇和骨密度相关联,采用胆固醇喂养的兔子髋部的骨小梁减少[75]。该作者认为,循环中血脂增加,导致脂质高度聚集在血管组织及动脉壁[75],脂蛋白微粒进入血管壁以后会导致氧化应激,从而诱导炎症反应发生,最终引起斑块形成[76]。由于成骨细胞前体与内皮下骨血管基质相临,因此上述病理过程会影响骨形成细胞的功能[77]。胆固醇及其代谢产物在体内和体外试验中都影响着成骨细胞的功能活动[76,77]。Sivas等[78]在土耳其绝经后女性中进行的研究显示,血脂谱的改变和骨密度没有显著的相关性,但是与脊椎骨折的发生存在显著相关性。对所调查人群的年龄、绝经年数、体质指数及血脂成分进行logistic回归分析发现,TC是骨质疏松发生的最强影响因素,平均每升高1mg/dl可以使脊椎骨折发生风险降低2.2%。日本学者Yamaguchi[79]也认为,适度的内脏脂肪的聚集是骨代谢的一个保护因素。Cui等[8]研究发现,血清胆固醇水平与绝经前女性腰椎骨密度、绝经后女性髋部骨密度呈负相关,血清甘油三酯(trigly ceride,TG)水平与绝经后女性髋部骨密度呈正相关。该研究结果与Adami等的结果相一致[80]。

目前已经有很多关于HDL-C与骨密度之间关系的报道,尽管这些研究结果不一致。Yamaguchi等[81]认为两者之间呈正相关,但是Adami、D'Amelio、Buizert、Dennison、Zabaglia等[80,82-85]却认为两者是负相关。而Poli等[86]认为在绝经后女性中,两者之间无关联,这与Cui等[8]的研究结果相一致:在绝经前和绝经后女性中,腰椎和髋部骨密度与HDL-C无显著关系。中国学者Li[87]在790例中国绝经后女性的横断面研究中指出,跟较低的HDL-C患者相比,较高的HDL-C患者更容易患骨质疏松。HDL-C是心血管疾病的保护因素,却是骨质疏松的危险因素,这可能与如下因素有关[88,89]:首先,HDL-C和脂肪量直接相关。有研究表明非脂肪组织的比例越高,特别是肌肉组织越多,机械刺激作用越强。肌肉收缩会使骨骼处于紧张状态,这样就会通过骨细胞上的机械受体在骨皮质内外促进骨重建,使骨量和骨骼几何结构参数均增加,从而提高骨强度。而脂肪组织较多,则可能引起骨重建紊乱、骨量和骨结构参数下降,进而易于发生骨质疏松。其次,HDL-C对骨质疏松的影响还可能存在性别差异。研究表明TC和LDL-C是男性重要的心血管疾病风险因素,而在女性中HDL-C和TG却起着更为重要的作用。

影响骨代谢和脂代谢的临床药物

1. 他汀类药物

他汀类药物除了具有降低血脂的作用,还对骨密度具有正向作用。他汀类药物、骨质疏松、脂肪生成拥有共同的信号通路——RANKL/OPG[90,91]。辛伐他汀和洛伐他汀都可以促进骨形态发生蛋白-2(bone morphogenetic protein-2,BMP-2)mRNA的表达[67]。

尽管Lima[92]等认为他汀类药物对骨修复具有负向作用,但是大部分研究[93-96]表明,他汀类药物可以促进成骨细胞的活动并抑制破骨细胞,从而可以增加骨密度,预防骨质疏松,减少骨折发生率。故有学者提出[97],他汀类药物可以用来治疗骨质疏松,但是最小的有效剂量仍在探索中。

2. 雌激素

雌激素主要是用来治疗绝经后女性骨质疏松。雌激素的主要作用是降低骨转换、维持骨形成和骨吸收的动态平衡。骨细胞内有两种雌激素受体——ERα和ERβ,当雌激素与受体结合后,就会激活相关基因。脂肪组织是绝经后女性雌激素的主要来源,主要由雄激素在脂肪细胞通过芳香化作用转变而来。

综上所述,可见血脂谱对骨密度的影响仍存在争议,这可能与研究对象的种族、年龄、性别、基础疾病状态以及研究方法等不同有关。此外,一项针对骨质疏松和心血管疾病相互关系的研究[98]发现,动脉粥样硬化过程而非血脂本身更加速骨量的丢失。血管壁动脉粥样硬化斑块形成过程中释放较多的炎症因子和脂肪因子,这些因子可能对骨质疏松的发生发展起着更为重要的作用。脂代谢对骨质疏松的影响涉及血脂本身、脂肪分布、脂肪因子、炎症因子等多方面,其对骨质疏松的最终影响也取决于各因素间的平衡。

[1] Kiel DP, Kauppila LI, Cupples LA, et al. Bone loss and the progression of abdominal aortic calcification over a 25 year period: the Framingham Heart Study[J]. Calcif Tissue Int, 2001, 68(5): 271-276.

[2] Hak AE, Pols HA, van Hemert AM, et al. Progression of aortic calcification is associated with metacarpal bone loss during menopause: a population-based longitudinal study[J]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2000, 20(8): 1926-1931.

[3] Fleet JC, Hock JM. Identification of osteocalcin mRNA in nonosteoid tissue of rats and humans by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 1994, 9(10): 1565-1573.

[4] Giachelli CM, Liaw L, Murry CE, et al. Osteopontin expression in cardiovascular diseases[J]. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 1995, 760: 109-126.

[5] Vogt MT, San Valentin R, Forrest KY, et al. Bone mineral density and aortic calcification: the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 1997, 45(2): 140-145.

[6] Ouchi Y, Akishita M, de Souza AC, et al. Age-related loss of bone mass and aortic/aortic valve calcification--reevaluation of recommended dietary allowance of calcium in the elderly[J]. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 1993, 676: 297-307.

[7] Hirose K, Tomiyama H, Okazaki R, et al. Increased pulse wave velocity associated with reduced calcaneal quantitative osteo-sono index: possible relationship between atherosclerosis and osteopenia[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2003, 88: 2573-2578.

[8] Cui LH, Shin MH, Chung EK, et al. Association between bone mineral densities and serum lipid profiles of pre- and post-menopausal rural women in South Korea[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2005, 16: 1975-1981.

[9] Rosen CJ, Klibanski A. Bone, fat, and body composition: evolving concepts in the pathogenesis of osteoporosis[J]. Am J Med, 2009, 122: 409-414.

[10] Tian L, Yu X. Lipid metabolism disorders and bone dysfunction--interrelated and mutually regulated(review)[J]. Mol Med Rep, 2015, 12: 783-794.

[11] Dantas AT, Pereira MC, de Melo Rego MJ, et al. The Role of PPAR Gamma in Systemic Sclerosis[J]. PPAR Res, 2015, 2015: 124624.

[12] Marx N, Bourcier T, Sukhova GK, et al. PPARgamma activation in human endothelial cells increases plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 expression: PPARgamma as a potential mediator in vascular disease[J]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 1999, 19: 546-551.

[13] Ricote M, Li AC, Willson TM, et al. The peroxisome proliferatoractivated receptor-gamma is a negative regulator of macrophage activation[J]. Nature, 1998, 391: 79-82.

[14] Sarraf P, Mueller E, Jones D, et al. Differentiation and reversal of malignant changes in colon cancer through PPAR gamma[J]. Nat Med, 1998, 4: 1046-1052.

[15] Lecka-Czernik B, Moerman EJ, Grant DF, et al. Divergent effects of selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma 2 ligands on adipocyte versus osteoblast differentiation[J]. Endocrinology, 2002, 143: 2376-2384.

[16] Kumar A, Singh AK, Gautam AK, et al. Identification of kaempferolregulated proteins in rat calvarial osteoblasts during mineralization by proteomics[J]. Proteomics, 2010, 10: 1730-1739.

[17] Chan BY, Gartland A, Wilson PJ, et al. PPAR agonists modulate human osteoclast formation and activity in vitro[J]. Bone, 2007, 40: 149-159.

[18] Hassumi MY, Silva-Filho VJ, Campos-Junior JC, et al. PPAR-gamma agonist rosiglitazone prevents inflammatory periodontal bone loss by inhibiting osteoclastogenesis[J]. Int Immunopharmacol, 2009, 9: 1150-1158.

[19] Wei W, Wang X, Yang M, et al. PGC1beta mediates PPARgamma activation of osteoclastogenesis and rosiglitazone-induced bone loss[J]. Cell Metab, 2010, 11: 503-516.

[20] Laudes M. Role of WNT signalling in the determination of human mesenchymal stem cells into preadipocytes[J]. J Mol Endocrinol, 2011, 46: R65-72.

[21] Hofbauer LC, Heufelder AE. Clinical review 114: hot topic. The role of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand and osteoprotegerin in the pathogenesis and treatment of metabolic bone diseases[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2000, 85: 2355-2363.

[22] Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, et al. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation[J]. Cell, 1998, 93: 165-176.

[23] Ayina CN, Sobngwi E, Essouma M, et al. Osteoprotegerin in relation to insulin resistance and blood lipids in sub-Saharan African women with and without abdominal obesity[J]. Diabetol Metab Syndr, 2015, 7: 47.

[24] Bennett BJ, Scatena M, Kirk EA, et al. Osteoprotegerin inactivation accelerates advanced atherosclerotic lesion progression and calcification in older ApoE-/- mice[J]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2006, 26: 2117-2124.

[25] Ayina CN, Boudou P, Fidaa I, et al. Osteoprotegerin is not a determinant of metabolic syndrome in sub-Saharan Africans after age adjustment[J]. Ann Endocrinol(Paris), 2014, 75: 165-170.

[26] urner RT, Kalra SP, Wong CP, et al. Peripheral leptin regulates bone formation[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2013, 28: 22-34.

[27] Thomas T, Gori F, Khosla S, et al. Leptin acts on human marrow stromal cells to enhance differentiation to osteoblasts and to inhibit differentiation to adipocytes[J]. Endocrinology, 1999, 140: 1630-1638.

[28] Reseland JE, Syversen U, Bakke I, et al. Leptin is expressed in and secreted from primary cultures of human osteoblasts and promotes bone mineralization[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2001, 16: 1426-1433.

[29] Cornish J, Callon KE, Bava U, et al. Leptin directly regulates bone cell function in vitro and reduces bone fragility in vivo[J]. J Endocrinol, 2002, 175: 405-415.

[30] Lai CF, Chaudhary L, Fausto A, et al. Erk is essential for growth, differentiation, integrin expression, and cell function in human osteoblastic cells[J]. J Biol Chem, 2001, 276: 14443-14450.

[31] Hu E, Kim JB, Sarraf P, et al. Inhibition of adipogenesis through MAP kinase-mediated phosphorylation of PPARgamma[J]. Science, 1996, 274: 2100-2103.

[32] Gordeladze JO, Drevon CA, Syversen U, et al. Leptin stimulates human osteoblastic cell proliferation, de novo collagen synthesis, and mineralization: Impact on differentiation markers, apoptosis, and osteoclastic signaling[J]. J Cell Biochem, 2002, 85: 825-836.

[33] Burguera B, Hofbauer LC, Thomas T, et al. Leptin reduces ovariectomyinduced bone loss in rats[J]. Endocrinology, 2001, 142: 3546-3553.

[34] Gabay C, Dreyer M, Pellegrinelli N, et al. Leptin directly induces the secretion of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist in human monocytes[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2001, 86: 783-791.

[35] Iwaniec UT, Boghossian S, Lapke PD, et al. Central leptin gene therapy corrects skeletal abnormalities in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice[J]. Peptides, 2007, 28: 1012-1019.

[36] Thomas T, Burguera B, Melton LJ, et al. Role of serum leptin, insulin, and estrogen levels as potential mediators of the relationship between fat mass and bone mineral density in men versus women[J]. Bone, 2001, 29: 114-120.

[37] Goulding A, Taylor RW. Plasma leptin values in relation to bone mass and density and to dynamic biochemical markers of bone resorption and formation in postmenopausal women[J]. Calcif Tissue Int, 1998, 63: 456-458.

[38] Yamauchi M, Sugimoto T, Yamaguchi T, et al. Plasma leptin concentrations are associated with bone mineral density and the presence of vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women[J]. Clin Endocrinol(Oxf), 2001, 55: 341-347.

[39] Ruhl CE, Everhart JE. Relationship of serum leptin concentration with bone mineral density in the United States population[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2002, 17: 1896-1903.

[40] Blain H, Vuillemin A, Guillemin F, et al. Serum leptin level is a predictor of bone mineral density in postmenopausal women[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2002, 87: 1030-1035.

[41] Zoico E, Zamboni M, Adami S, et al. Relationship between leptin levels and bone mineral density in the elderly[J]. Clin Endocrinol(Oxf), 2003, 59: 97-103.

[42] Pasco JA, Henry MJ, Kotowicz MA, et al. Serum leptin levels are associated with bone mass in nonobese women[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2001, 86: 1884-1887.

[43] Ushiroyama T, Ikeda A, Hosotani T, et al. Inverse correlation between serum leptin concentration and vertebral bone density in postmenopausal women[J]. Gynecol Endocrinol, 2003, 17: 31-36.

[44] Blum M, Harris SS, Must A, et al. Leptin, body composition and bone mineral density in premenopausal women[J]. Calcif Tissue Int, 2003, 73: 27-32.

[45] Ducy P, Amling M, Takeda S, et al. Leptin inhibits bone formation through a hypothalamic relay: a central control of bone mass[J]. Cell, 2000, 100: 197-207.

[46] Kim GS, Hong JS, Kim SW, et al. Leptin induces apoptosis via ERK/cPLA2/cytochrome c pathway in human bone marrow stromal cells[J]. J Biol Chem, 2003, 278: 21920-21929.

[47] Hamrick MW, Ferrari SL. Leptin and the sympathetic connection of fat to bone[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2008, 19: 905-912.

[48] Scherer PE, Williams S, Fogliano M, et al. A novel serum protein similar to C1q, produced exclusively in adipocytes[J]. J Biol Chem, 1995, 270: 26746-26749.

[49] Maeda K, Okubo K, Shimomura I, et al. cDNA cloning and expression of a novel adipose specific collagen-like factor, apM1(AdiPose Most abundant Gene transcript 1)[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 1996, 221: 286-289.

[50] Nakano Y, Tobe T, Choi-Miura NH, et al. Isolation and characterization of GBP28, a novel gelatin-binding protein purified from human plasma[J]. J Biochem, 1996, 120: 803-812.

[51] Dennis JE, Charbord P. Origin and differentiation of human and murine stroma[J]. Stem Cells, 2002, 20: 205-214.

[52] Berner HS, Lyngstadaas SP, Spahr A, et al. Adiponectin and its receptors are expressed in bone-forming cells[J]. Bone, 2004, 35: 842-849.

[53] Luo XH, Guo LJ, Yuan LQ, et al. Adiponectin stimulates human osteoblasts proliferation and differentiation via the MAPK signaling pathway[J]. Exp Cell Res, 2005, 309: 99-109.

[54] Oshima K, Nampei A, Matsuda M, et al. Adiponectin increases bone mass by suppressing osteoclast and activating osteoblast[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2005, 331: 520-526.

[55] Kajimura D, Lee HW, Riley KJ, et al. Adiponectin regulates bone mass via opposite central and peripheral mechanisms through FoxO1[J]. Cell Metab, 2013, 17: 901-915.

[56] Luo XH, Guo LJ, Xie H, et al. Adiponectin stimulates RANKL and inhibits OPG expression in human osteoblasts through the MAPK signaling pathway[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2006, 21: 1648-1656.

[57] Mitsui Y, Gotoh M, Fukushima N, et al. Hyperadiponectinemia enhances bone formation in mice[J]. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 2011, 12: 18.

[58] Ealey KN, Kaludjerovic J, Archer MC, et al. Adiponectin is a negative regulator of bone mineral and bone strength in growing mice[J]. Exp Biol Med(Maywood), 2008, 233: 1546-1553.

[59] Yano W, Kubota N, Itoh S, et al. Molecular mechanism of moderate insulin resistance in adiponectin-knockout mice[J]. Endocr J, 2008, 55: 515-522.

[60] Nawrocki AR, Rajala MW, Tomas E, et al. Mice lacking adiponectin show decreased hepatic insulin sensitivity and reduced responsiveness to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists[J]. J Biol Chem, 2006, 281: 2654-2660.

[61] Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Yamauchi T, et al. Disruption of adiponectin causes insulin resistance and neointimal formation[J]. J Biol Chem, 2002, 277: 25863-25866.

[62] Maeda N, Shimomura I, Kishida K, et al. Diet-induced insulin resistance in mice lacking adiponectin/ACRP30[J]. Nat Med, 2002, 8: 731-737.

[63] Cole ZA, Dennison EM, Cooper C. Osteoporosis epidemiology update[J]. Curr Rheumatol Rep, 2008, 10: 92-96.

[64] Nguyen ND, Ahlborg HG, Center JR, et al. Residual lifetime risk of fractures in women and men[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2007, 22: 781-788.

[65] Pinheiro MM, Reis Neto ET, Machado FS, et al. Risk factors for osteoporotic fractures and low bone density in pre and postmenopausal women[J]. Rev Saude Publica, 2010, 44: 479-485.

[66] Wang PS, Solomon DH, Mogun H, et al. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and the risk of hip fractures in elderly patients[J]. JAMA, 2000, 283: 3211-3216.

[67] Mundy G, Garrett R, Harris S, et al. Stimulation of bone formation in vitro and in rodents by statins[J]. Science, 1999, 286: 1946-1949.

[68] Meier CR, Schlienger RG, Kraenzlin ME, et al. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and the risk of fractures[J]. JAMA, 2000, 283: 3205-3210.

[69] Schoofs MW, Sturkenboom MC, van der Klift M, et al. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and the risk of vertebral fracture[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2004, 19: 1525-1530.

[70] Orozco P. Atherogenic lipid profile and elevated lipoprotein(a) are associated with lower bone mineral density in early postmenopausal overweight women[J]. Eur J Epidemiol, 2004, 19: 1105-1112.

[71] Samelson EJ, Cupples LA, Hannan MT, et al. Long-term effects of serum cholesterol on bone mineral density in women and men: the Framingham Osteoporosis Study[J]. Bone, 2004, 34: 557-561.

[72] Perez-Castrillon JL, De Luis D, Martin-Escudero JC, et al. Non-insulindependent diabetes, bone mineral density, and cardiovascular risk factors[J]. J Diabetes Complications, 2004, 18: 317-321.

[73] Tanko LB, Bagger YZ, Nielsen SB, et al. Does serum cholesterol contribute to vertebral bone loss in postmenopausal women?[J]. Bone, 2003, 32: 8-14.

[74] Wu LY, Yang TC, Kuo SW, et al. Correlation between bone mineral density and plasma lipids in Taiwan[J]. Endocr Res, 2003, 29: 317-325.

[75] Bartels T, Beitz J, Hein W, et al. Changes in the spongiosa density in the femoral head of rabbits in atherosclerosis[J]. Beitr Orthop Traumatol, 1990, 37: 291-297.

[76] Parhami F, Garfinkel A, Demer LL. Role of lipids in osteoporosis[J]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2000, 20: 2346-2348.

[77] Parhami F, Morrow AD, Balucan J, et al. Lipid oxidation products have opposite effects on calcifying vascular cell and bone cell differentiation. A possible explanation for the paradox of arterial calcification in osteoporotic patients[J]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 1997, 17: 680-687.

[78] Sivas F, Alemdaroglu E, Elverici E, etal. Serum lipid profile: its relationship with osteoporotic vertebrae fractures and bone mineral density in Turkish postmenopausal women[J]. Rheumatol Int, 2009, 29: 885-890.

[79] Yamaguchi T. Bone metabolism in dyslipidemia and metabolic syndrome[J]. Clin Calcium, 2011, 21: 677-682.

[80] Adami S, Braga V, Zamboni M, et al. Relationship between lipids and bone mass in 2 cohorts of healthy women and men[J]. Calcif Tissue Int, 2004, 74: 136-142.

[81] Yamaguchi T, Sugimoto T, Yano S, et al. Plasma lipids and osteoporosis in postmenopausal women[J]. Endocr J, 2002, 49: 211-217.

[82] D'Amelio P, Pescarmona GP, Gariboldi A, et al. High density lipoproteins(HDL) in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a preliminary study[J]. Menopause, 2001, 8: 429-432.

[83] Buizert PJ, van Schoor NM, Lips P, et al. Lipid levels: a link between cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis?[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2009, 24: 1103-1109.

[84] Dennison EM, Syddall HE, Aihie Sayer A, et al. Lipid profile, obesity and bone mineral density: the Hertfordshire Cohort Study[J]. QJM, 2007, 100: 297-303.

[85] Zabaglia SF, Pedro AO, Pinto Neto AM, et al. An exploratory study of the association between lipid profile and bone mineral density in menopausal women in a Campinas reference hospital[J]. Cad Saude Publica, 1998, 14: 779-786.

[86] Poli A, Bruschi F, Cesana B, et al. Plasma low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and bone mass densitometry in postmenopausal women[J]. Obstet Gynecol, 2003, 102: 922-926.

[87] Li S, Guo H, Liu Y, et al. Relationships of serum lipid profiles and bone mineral density in postmenopausal Chinese women[J]. Clin Endocrinol(Oxf), 2015, 82: 53-58.

[88] Hsu YH, Venners SA, Terwedow HA, et al. Relation of body composition, fat mass, and serum lipids to osteoporotic fractures and bone mineral density in Chinese men and women[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2006, 83: 146-154.

[89] D'Amelio P, Di Bella S, Tamone C, et al. HDL cholesterol and bone mineral density in normal-weight postmenopausal women: is there any possible association?[J]. Panminerva Med, 2008, 50: 89-96.

[90] Savopoulos C, Dokos C, Kaiafa G, et al. Adipogenesis and osteoblastogenesis: trans-differentiation in the pathophysiology of bone disorders[J]. Hippokratia, 2011, 15: 18-21.

[91] Song C, Guo Z, Ma Q, et al. Simvastatin induces osteoblastic differentiation and inhibits adipocytic differentiation in mouse bone marrow stromal cells[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2003, 308: 458-462.

[92] Lima CE, Calixto JC, Anbinder AL. Influence of the association between simvastatin and demineralized bovine bone matrix on bone repair in rats[J]. Braz Oral Res, 2011, 25: 42-48.

[93] Saraf SK, Singh A, Garbyal RS, et al. Effect of simvastatin on fracture healing--an experimental study[J]. Indian J Exp Biol, 2007, 45: 444-449.

[94] Wang JW, Xu SW, Yang DS, et al. Locally applied simvastatin promotes fracture healing in ovariectomized rat[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2007, 18: 1641-1650.

[95] Nyan M, Sato D, Oda M, et al. Bone formation with the combination of simvastatin and calcium sulfate in critical-sized rat calvarial defect[J]. J Pharmacol Sci, 2007, 104: 384-386.

[96] Skoglund B, Aspenberg P. Locally applied Simvastatin improves fracture healing in mice[J]. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 2007, 8: 98.

[97] Uzzan B, Cohen R, Nicolas P, et al. Effects of statins on bone mineral density: a meta-analysis of clinical studies[J]. Bone, 2007, 40: 1581-1587.

[98] Bagger YZ, Rasmussen HB, Alexandersen P, et al. Links between cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: serum lipids or atherosclerosis per se?[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2007, 18: 505-512.