Mapping the quality of prenatal and postnatal care and demographic differences on child mortality in 26 low to middle-income countries

Kelly Lin · Serena Chern · Jing Sun

Abstract Background Closing the gap between child mortality in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) and high-income countries is a priority set by the WHO in sustainable development goals (SDGs).We aimed to examine poor nutrition and prenatal and postnatal care that could increase the risk of child mortality in LMICs.Methods The Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) was used to examine data from 26 countries to compare prenatal,postnatal,nutritional,and demographic factors across LMICs.Outcome of child death was classified into death before one month of age,between 1 to 11 months,between one to two years,between three to five years,and overall death before five years.Chi-square analyses identified differences in prenatal care,postnatal care,nutrition,and demographic factors between children who died and those who survived.Logistic regression identified factors that increased child mortality risk.Results The majority of deaths occurred before the ages of one month and one year.Considerably poorer quality of prenatal care,postnatal care,and nutrition were found in low-income and low-middle-income countries in the contemporary 2020s.High child mortality and poor quality of prenatal and postnatal care coincide with low income.Children in LMICs were exposed to less vitamin A-rich foods than children in higher-middle-income countries.The use of intestinal parasite drugs and the absence of postpartum maternal vitamin A supplementation significantly increased child mortality risk.Significant socio-demographic risk factors were associated with an increased mortality rate in children,including lack of education,maternal marital status,family wealth index,living rurally,and financial problems hindering access to healthcare.Conclusions Poor nutrition remains a vital factor across all LMICs,with numerous children being exposed to foods low in iron and vitamin A.Significantly,most deaths occur in neonates and infants,indicating an urgent need to address risk factors associated with early child death.

Keywords Child mortality · Low-and middle-income countries · Postnatal care · Prenatal care

Despite a substantial global reduction in under-five mortality (U5M) since 1990,1 in 27 children still dies before reaching the age of 5 [1].The highest rate of child mortality is observed in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs),accounting for more than 80% of U5M in 2020 [1].Closing the gap in child mortality is a priority set by the WHO in sustainable development goals (SDGs).

Previous studies have estimated cause-specific mortality for children,including infectious diseases such as meningitis,measles,lower respiratory infections and birth complications [2].However,various other risk factors also contribute to the disparity of U5M between LMICs and high-income countries,including malnutrition,barriers to accessing health facilities,and demographic factors including education,income level,marital status,and place of residence[3–8].The effects of nutrition and the quality of prenatal and postnatal care in LMICs have been less researched.

Introduction

WHO guidelines suggest that mothers should receive at least four prenatal appointments,along with blood pressure,urine and blood tests to screen for maternal comorbidities,which could increase the risk of child morbidity and mortality [9].In LMICs,specific prenatal components have also been developed to target nutritional deficiencies and endemic infections.Iron supplementation has been specifically indicated in LMICs,where up to 52% of pregnant women are affected by iron deficiency anemia,which is associated with intrauterine growth retardation,low birth weight,and increased infant mortality risk [10].Anti-parasitic medications also form part of prenatal care in LMICs[11,12].Intestinal parasite infections contribute to maternal anemia while also causing malabsorption of nutrients,diarrhea,and abdominal pain [12].This leads to lower birth weights,higher infection risk,and higher infant mortality [11].However,previous meta-analyses on antiparasitic drug use in pregnant women found variable improvements in maternal anemia,birth weight,and infant mortality [13,14].

Postnatal care acts as a continuum of care for both mothers and infants.This helps provide critical early treatment in preventing complications,as the majority of maternal and neonatal deaths occur in the first week [15,16].

Early vitamin A supplementation is another crucial aspect of postnatal care in LMICs with limited nutritional diversity,as vitamin A is vital for immune function,red blood cell production,vision and cell maintenance [4,17].Infants are naturally born with low stores of vitamin A and depend on breast milk to meet their physiological needs for vitamin A[18].Previously,the WHO recommended vitamin A supplementation for mothers living in LMICs within the first six months after giving birth,as poor nutritional diversity reduces vitamin A concentrations in breast milk [19].However,guidelines have been revised due to contrasting results[20,21].The current WHO recommendation is to give vitamin A to infants and children within 6 to 59 months [22].Despite the recognized benefits of vitamin A in reducing child mortality and morbidity,the WHO reported that only 41% of children targeted for supplementation were reached in 2020,highlighting a significant gap [5].

In LMICs,the poor quality of prenatal and postnatal services is often reflected in their lack of basic equipment required to conduct adequate procedures [6].Sociodemographic factors,including poor wealth index,low level of health insurance coverage,poor living standards,and limited availability of health facilities,are common factors hindering access to qualified prenatal and postnatal services [8,23].Education level is another factor linked to the wealth index that influences child mortality in addition to maternal marital status [24].Earlier studies found that mothers that are not married had higher infant mortality rates,which may be associated with increased psychological and financial stress to provide for their child [25].

Given the protective factors of qualified prenatal and postnatal care,this study aims to address the research gap by mapping the quality of prenatal and postnatal care in LMICs and identifying the risks of child mortality associated with poor prenatal and postnatal care.The consumption of iron-and vitamin A-rich foods will also be mapped to identify patterns of poor nutrition in LMICs.Through identifying factors that increase child mortality risk,policies and interventions can be devised to help close the gap in child mortality between LMICs and high-income countries.

Methods

Data sources

Data for this study were retrieved from the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS),a freely available open-source dataset.From the “children” dataset,information relating to pregnancy,postnatal care,immunization,and health was surveyed.Most recent data ranging from 2013 to 2020 from 26 countries were merged to compare prenatal,postnatal and demographic factors across LMICs.These countries were Afghanistan (2015),Angola (2016),Armenia (2016),Bangladesh (2018),Benin (2018),Cameroon (2018),Colombia(2015),Egypt (2014),Ethiopia (2016),Ghana (2014),Guinea (2018),Haiti (2017),India (2016),Indonesia (2017),Jordan (2018),Liberia (2020),Mali (2018),Nepal (2016),Nigeria (2018),Pakistan (2013),the Philippines (2017),Senegal (2019),Sierra Leone (2019),Tanzania (2016),Zambia (2018) and Timor (2016).Countries that did not report age of death were excluded.

Ethics

Data analyzed in this study were accessed from a freely available open-sourced DHS dataset.Permission was provided to the principal supervisor and all collaborators for use,so no ethics application was needed.

Study variables—prenatal care,postnatal care and demographic factors

Classification of countries based on income level

To analyze the differences in healthcare and demographic factors,countries were classified by income level.Definitions based on gross national income (GNI) per capita in current USD published by The World Bank in 2021 were used [26].Countries with <1045 GNI per capita were classified as low-income countries (LICs);GNI between 1046 to 4095 were classified as lower-middle-income countries(lower-MICs),and GNI between 4096 to 12,695 were classified as upper-middle income countries (upper-MICs).

Prenatal factors

The main prenatal indicators recommended by the WHO,blood pressure,urine samples,and blood tests,were included.These prenatal checks were also assessed via the person who conducted them: doctor,nurse/midwife,traditional birth attendant,and no one.Whether or not mothers were educated about pregnancy complications,use of iron tablets,and intestinal parasite drugs were also examined.

Postnatal factors

Two factors of postnatal care were analyzed: postnatal check-ups and vitamin A supplementation within the first two months after giving birth.

Demographic factors

The following demographic factors were analyzed to measure health service accessibility,education,marital status,wealth,and residence:

• Covered by health insurance (yes/no)

• Type of residence (urban/rural)

• Highest education level of mother (none,primary education,secondary education,higher education)

• Wealth index (poorest,poor,middle,richer,richest)

• Receiving medical help:

• Money needed for treatment (little to no problem/big problem)

• Distance to health facility (little to no problem/big problem)

• Marital status: currently in union/living with a man,formerly in union/living with a man,never in union/lived with a man

Two of these variables,“getting money needed for treatment” and “distance to health facility”,were recoded.The answers “not a big problem” and “little problem” were combined to form “little to no problem”,which was then compared to those who had “big problem[s]”.

Age of death

Child mortality was separated into death under one month,death between one and 11 months,death between one and two years,death between three and five years,and overall death under five years.Since the postnatal factors were measured within the first two months of birth,only infant death (under 12 months) was analyzed rather than neonatal death within the first 28 days of birth.

Statistical analysis

Among children who died at different ages,chi-square analysis was conducted to assess the inequalities in prenatal and postnatal care and the differences in demographic factors across LICs,lower-MICs,and upper-MICs.Chi-square analyses were performed to compare and identify the distribution of age of mortality.

Logistic regression models were used to estimate the effects of the quality of prenatal and postnatal care on overall child mortality considering demographic variables that influence the accessibility of care.Two logistic regression models were used to analyze mortality under the age of one and five.The Hosmer and Lemeshow test was used to determine the goodness of fit of each model.Since most deaths occurred before the age of one,death between one to two,and death between three to five were not modeled using logistic regression.

Results

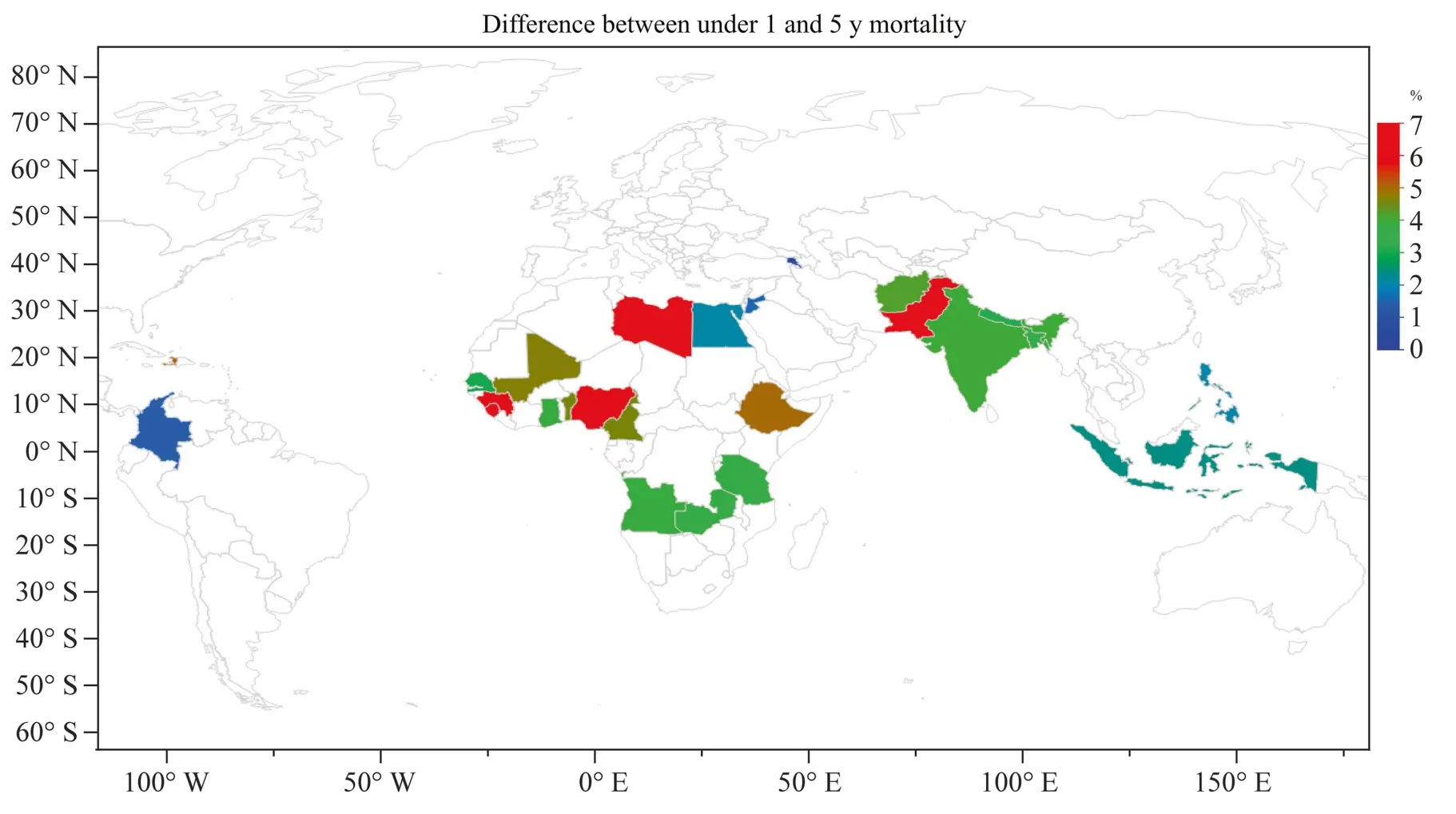

Table 1 provides an overview of child mortality at the global,regional and country levels.The global mortality rate for children under five in LMICs was 5% (n=27,129,P<0.001),while under one month death was 2.8% (n=15,039,P<0.001),accounting for 56% of U5M.Death between 1 and 11 months of age accounted for 1.5% (n=7701,P<0.001) of U5M.Countries were further divided based on income.Significantly higher mortality rates at all ages were observed in LICs (U5M=6.4,P<0.001) and lower-MICs[U5M=4.9%,95% confidence interval (CI)=0.049–0.050]than in upper-MICs (U5M=1.6%,P<0.001).Figures 1 a,b,and c map the prevalence of child mortality across three age groups in the 26 countries analyzed.The greatest percentage of deaths was found in African countries—Nigeria(U5M=9.5%,P<0.001),Guinea (U5M=8.5%,P<0.001),and Sierra Leone (U5M=8.4%,P<0.001).

As indicated in Table 1 and Fig. 1,most deaths occurred in neonates under one month of age or infants under one year of age.Figure 2 demonstrates the difference between deaths under one year and under five years,further indicating that most deaths occurred under one year of age.Thus,further analysis to identify factors associated with increased mortality risk was analyzed specifically for deaths under one and overall U5M.Neonatal death was not further analyzed,as the postnatal factors examined in this study were measured up to two months of age.

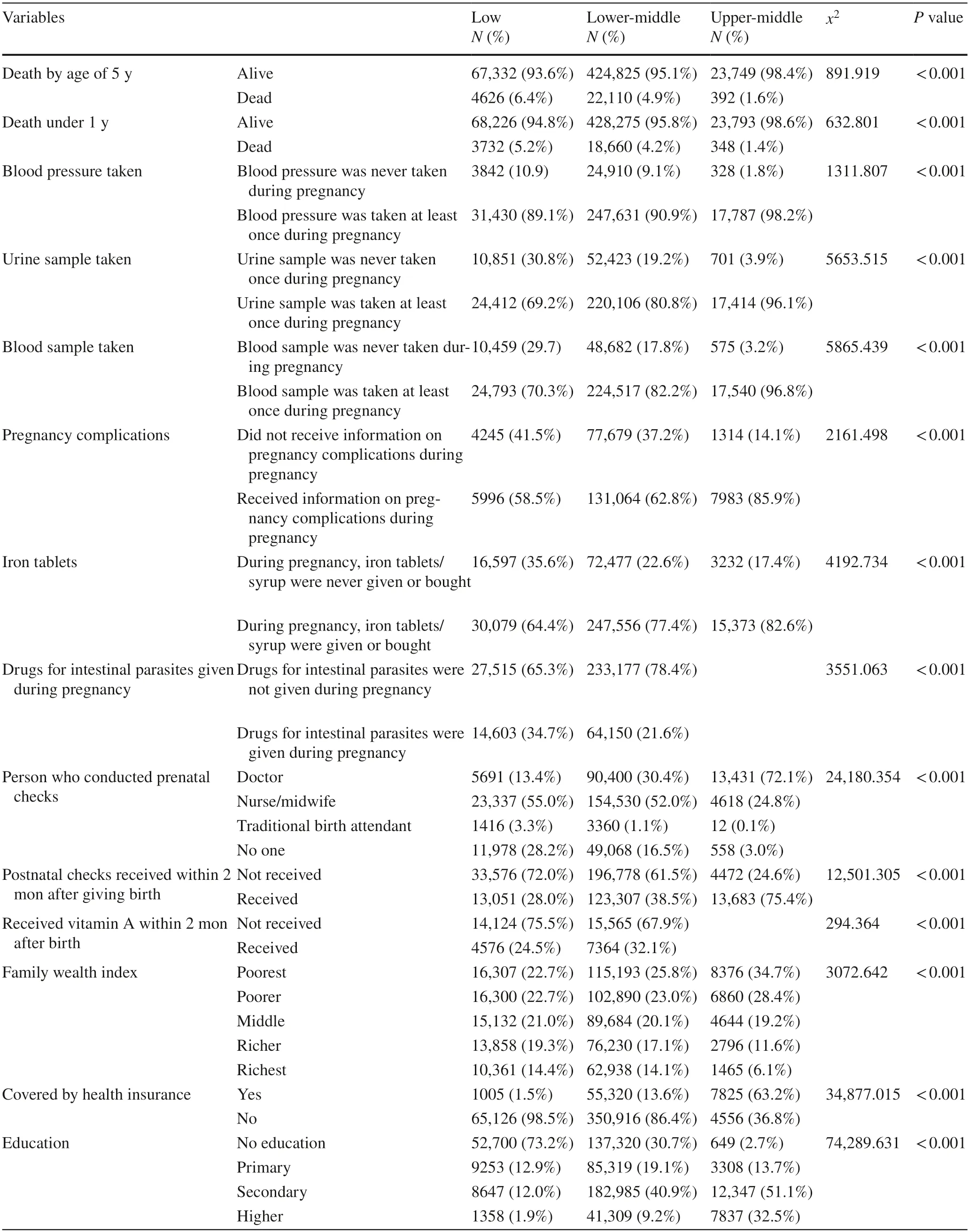

Table 2 displays differences in the quality of prenatal and postnatal care as well as demographic factors on child mortality.Significant differences exist in all aspects of prenatal and postnatal services and demographic factors between children who lived past the age of one and thosewho did not.Similar significant results were observed in U5M.Of the children who did not live past the age of one,more mothers did not have their blood pressure,urine or blood sample taken during pregnancy.In addition,they never took iron tablets during their pregnancy (4.5% compared to 2.9%).Most mothers of children who died by the age of five did not have prenatal checks (5.1%) compared to having doctors (2.4%),nurses/midwives (3.2%),or traditional birth attendants (4.0%) to conduct a prenatal check.For postnatal care,more mothers of children who died by the age of one had not received their postnatal check (4.1%compared to 2.0%) and vitamin A supplementation (4.0%compared to 2.0%) within the first two months after giving birth.

Fig.2 Difference between under 1 y and 5 y mortality.The figure was created using an open access data from the DHS survey created with JMP®,version 16.SAS institute.,Cary,NC,1989–2022

Analysis of demographic factors found that a greater percentage of children who died by the age of five belonged to mothers with no education (6.6% compared to 2.4%),poor wealth index (6.2% compared to 3.1%),and resided rurally(5.5% compared to 3.9%).Similarly,significantly more mothers of children who died by the age of five reported distance (5.7% compared to 4.7%) and financial barriers preventing them from accessing healthcare (P<0.001).

When grouped based on income levels,significant differences were found in the distribution of child mortality and demographic factors,as well as the quality of prenatal and postnatal healthcare.Six countries were identified as LICs;17 countries were identified as lower-MICs,and three countries were identified as upper-MICs.Table 3 shows that most children who died before the age of one were from LICs (5.2%),followed by lower-MICS (4.2%) and upper-MICs (1.4%).

Table 3 Child mortality,health service and demographic variables by country’s income

Most mothers who did not have their blood pressure,urine sample and blood sample taken during pregnancy were from LICs.Almost half of the mothers in LICs (41.5%) did not receive information on pregnancy complications,followed by 37.2% in lower-MICs and 14.1% in upper-MICs.

For iron tablet use,a greater proportion of mothers in LICs (35.6%) had not received or bought iron tablets or syrup during their pregnancy compared to mothers of lower MICs (22.6%) and upper MICs (17.4%).In contrast,significantly more mothers of LICs were given intestinal parasite drugs (34.7%) compared to mothers of lower-MICs (21.6%).Most mothers of LICs received their prenatal checks from nurse/midwife (55.0%),followed by no prenatal checks(28.2%).In lower-MICs,most mothers had their prenatal examinations done by nurses/midwives (52.0%),followed by doctors (30.4%).In upper-MICs,most mothers received their prenatal checks by doctors (72.1%),followed by nurses(24.8%).

Although most mothers in LMICs received prenatal checks,only a minority received postnatal checks.In LICs,72.0% of children did not receive their postnatal check-up,and 75.5% of mothers did not receive vitamin A supplementation within two months after giving birth.

Differences in demographic factors also exist among countries with varying income levels.In terms of the mother’s highest level of education,most mothers in LICs(73.2%) received no education,whereas 40.9% of mothersin lower-MICs received secondary education,and 32.5%of mothers in upper-MICs received higher education.In LICs,more families lived in rural settings (73.9%) and had“big problems” accessing health facilities due to distance(56.4%) and money (63.6%).Most mothers from upper-MICs reported living in urban settings (72.1%) and had little to no problem accessing health care in terms of distance(74.6%) and money (70.4%).Most mothers from the three income brackets were currently in a union/living with a man.Table 4 identifies significant risk factors for U5M and child mortality under one year of age based on logistic regression results (Table 5).

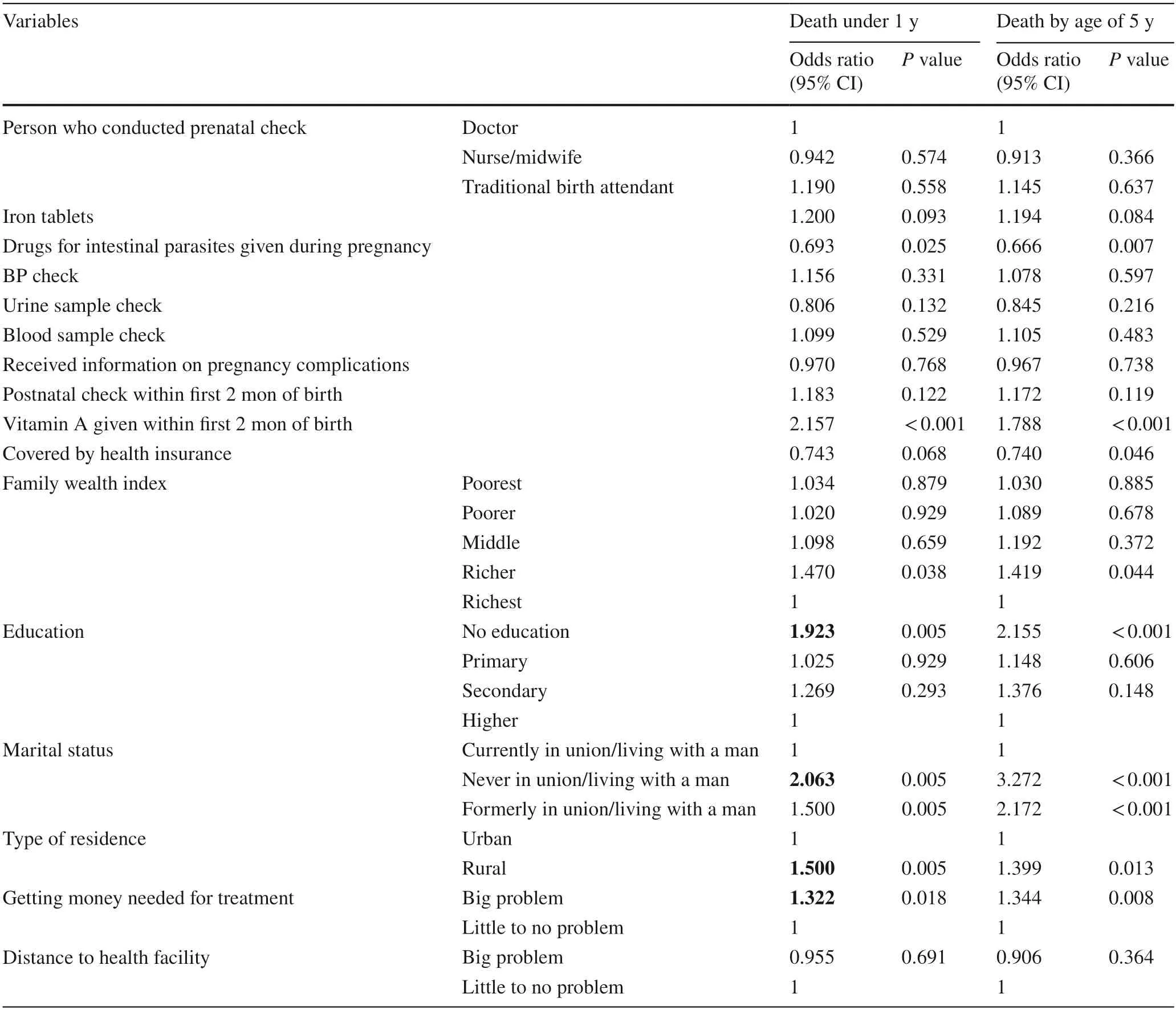

Table 4 Prenatal,postnatal and individual factors on risk of child mortality

Table 5 Nutritional and feeding habits by country wealth index

Intestinal parasitic drugs and lack of vitamin A supplementation also significantly increased child mortality risk.Children of mothers given intestinal parasitic drugs during pregnancy were about 1.35 times more likely to die by the age of five.Infants of mothers who did not receive vitamin A within the first two months after giving birth were 1.79 times more likely to die by the age of five.The marital status and education level of mothers also significantly increased child mortality risk.Compared to mothers with higher education,children of mothers with no education were approximately 2.2 times more likely to die by the age of five.When compared to mothers currently in unions,children of mothers who had never been in unions were approximately 3.3 times more likely to die by the age of five,and children of mothers formerly in unions were approximately 2.2 times more likely to die by the age of five.Living in a rural setting also increased child mortality risk by an age of five by 1.34 times.

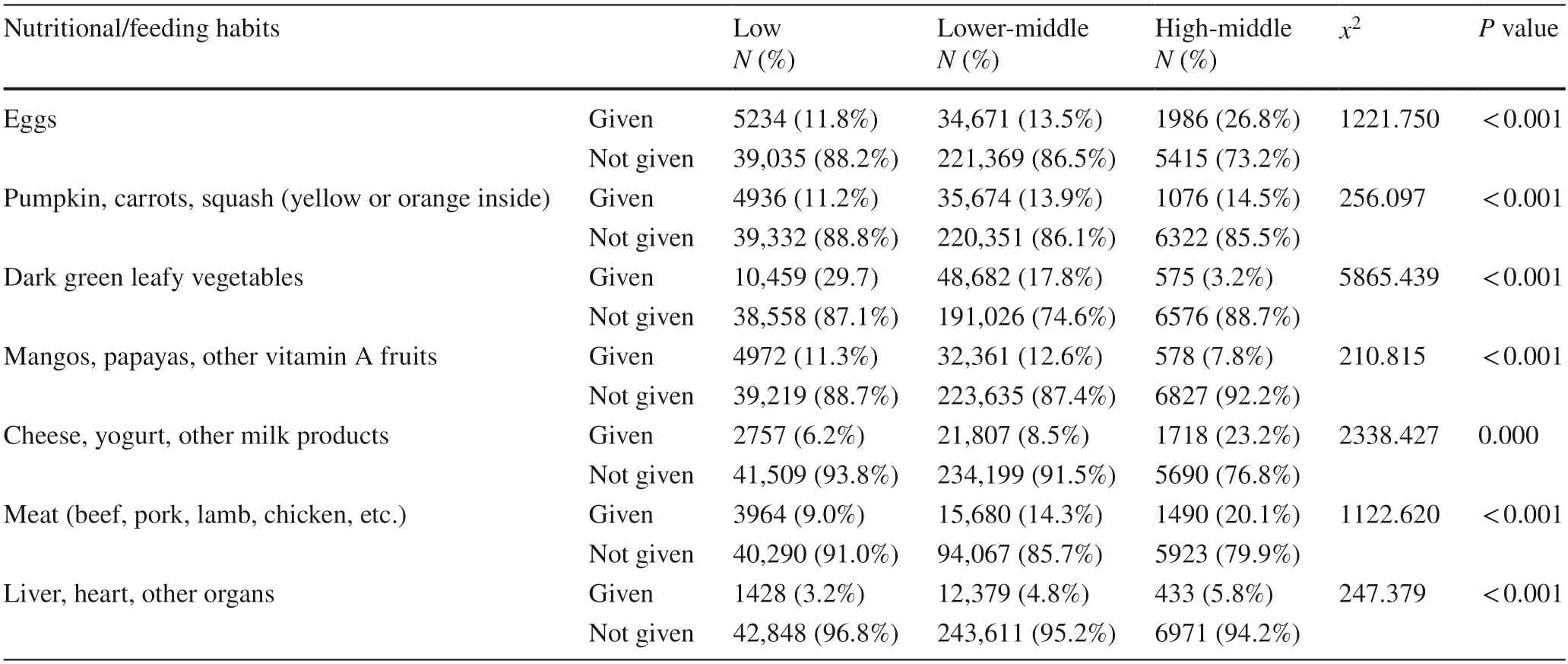

Chi-square tests were used to evaluate differences in nutrition and diet among children who survived past one and five years of age (Table 5, Table 6).Differences in dietary patterns in LICs,lower-MICs and upper-MICs were also analyzed.Seven groups of food were examined,including food rich in vitamin A,such as pumpkin,carrots,squash,egg,dairy products,fruits and iron-rich food,including dark leafy greens,meat,liver,heart,and other organs.Overall,a significantly greater portion of children who survived past the age of one,three and five were exposed to iron-rich and vitamin A-rich food.A significantly greater percentage of children in upper-MICs were given dairy,eggs,meat,pumpkin,carrots,squash,and animal organs,while those in LICs and lower-MICs were given more dark leafy vegetables and fruits.

Discussion

The results identified that most child mortality occurred before the age of one.Not receiving vitamin A within the first two months after giving birth and being given intestinal parasite medication during pregnancy were further identified as two significant risk factors of under one and U5M.

In line with the known risks of intestinal parasite infections in pregnant women and their offspring,the WHO recommends prophylactic intestinal parasite treatment in pregnant women residing in regions with endemic intestinal parasite infections [16].This corresponded with the results of this study,where significantly more mothers (34.7%) were given anthelmintics in LICs than in lower-MICs (21.6%).However,in this study,being given anthelmintics during pregnancy did not provide protection against child mortality;instead,it significantly increased mortality risk before the age of one and the age of five.In congruence with our results,varying effectiveness of intestinal parasite treatments in improving both maternal and child health outcomes have been identified previously [12,13].Different from randomized control studies,the specific timing,frequency,dosage,and type of anthelmintic use were not specified in the DHS survey.Being given anthelmintics during pregnancydoes not indicate that the mother has received or completed an adequate treatment course to clear infection.If anthelmintics are given in the first trimester,adverse impacts on fetal development may also contribute to increased child mortality [27].Thus,more detailed studies examining specific factors of anthelmintic use during pregnancy are required to inform better policies.

The absence of vitamin A treatment for mothers within the first two months after giving birth was another risk factor for child mortality.In terms of postpartum maternal vitamin A supplementation,the WHO has revised guidelines to remove recommendations for postpartum maternal vitamin A supplementation due to a lack of evidence [19].In line with the revised guidelines,this study found that most mothers in LICs (75.5%) and lower-MICs (67.9%) did not receive vitamin A supplementation within the first two months after giving birth.

However,postpartum vitamin A supplementation in mothers was identified as a protective factor in this study.Mothers who did not receive vitamin A within two months after giving birth were 2.157 times more likely to have their children die before the age of one and 1.788 times more likely to die before the age of five.Although conflicting literature exists regarding postpartum vitamin A supplementation,it is important to note that most randomized controlled trials were conducted in MICs where vitamin A deficiencies are not as prevalent as LICs [20].Vitamin A must be obtained through dietary sources,where its most active form is found in animal sources [4].However,as presented in Table 5,nutritional analysis found that significantly more children in LMICs were not given animal products.Less than 15% of children in LICs and lower-MICs were given egg,meat,or dairy products,highlighting a significant risk for vitamin A deficiency in LMICs.

Despite contrasting literature,beneficial effects of postpartum maternal vitamin A supplementation in reducing child mortality and morbidity have still been identified,as breast milk from well-nourished mothers is a rich source of vitamin A for infants [28].Significant improvements in vitamin A levels in breast milk have also been identified in mothers who received vitamin A supplementation postpartum [21].The protective factors of vitamin A supplementation may be explained by its role in ensuring normal growth,red blood cell production,immunity,and visual system development [4].Children under one year of age are especially vulnerable to infections and preterm complications,especially in LMICs with poor nutrition,water sanitation and healthcare accessibility [1].In children under one,breast milk is a critical source of vitamin A.Thus,in LMICs where vitamin A deficiency is an endemic issue across all ages,maternal supplementation may act as a low-cost intervention to ensure sufficient vitamin A concentrations are present within breast milk.This could then help protect against child mortality by reducing morbidities and ensuring healthy infant development.To clarify the effects of postpartum maternal vitamin A supplementation on child mortality and morbidity in at-risk populations,more studies and analyses are required based on LMIC populations.

Regarding access to prenatal and postnatal health checks,if the equipment required for testing is not available,the quality of healthcare delivered may be poor with limited benefits.Previous studies have revealed inadequate prenatal care facilities in LMICs,where only 2% of the surveyed met the WHO criteria for basic service readiness [6].This may explain the limited effects of prenatal care on child mortality found in this study.The wealth index,region of residence and other demographic factors may have a greater effect on child mortality,as they influence variables including nutritional status,water sanitation,and healthcare accessibility.

Two factors for accessibility to health care,finance and distance,were assessed in this study.Logistic regression analysis revealed that when distance is a “big problem”for accessing healthcare,the child is approximately 1.3 times more likely to die before the age of one (P=0.018).Distance (56.4%) and financial barriers (63.6%) posed a“big problem” to more mothers in LICs than mothers from lower-MICs and upper-MICs.Reasons such as inability to pay for medical bills,unequal access to health services,poor living conditions,and the lack of technical quality of healthcare may account for the high incidence in child mortality observed in lower-income households [8].As household wealth status determines access to health facilities,in poorer regions,there may be a lack of resources for prenatal testing,including urine,blood,and blood pressure testing [29].

One way to alleviate medical costs is by having health insurance provide coverage for maternity care.Unlike curative services,the benefits of preventive care,such as antenatal care,tend to be deferred,as women are less likely to pay for such services upfront [30].This could lead to financial shocks in the case of obstetric complications without preventive care.With coverage to defray costs,the economic barrier to seeking treatment is lessened.In our study,a greater portion of children who died under the age of five and one were not covered by health insurance,while “money as a problem” significantly increased the risk of U5M.This is consistent with previous studies indicating that total public expenditure allocated to healthcare in Sub-Saharan African LMICs is the lowest worldwide,while healthcare financing in these countries remains largely private and out-of-pocket[31].The benefits of government funding on healthcare have been further revealed through the evaluation of Ghana’s national health insurance,demonstrating that national health insurance significantly reduced the likelihood of neonatal deaths,as out-of-pocket payments act as an important barrier in accessing care in LMICs [32].Thus,increasing the allocation of public expenditure to health care and the development of national health insurance may be critical in reducing U5M.

Nonmarital status was another significant risk factor that increased child mortality risk.This may be attributed to that unmarried mothers are often younger and less educated with a lower socioeconomic status than married mothers [3].Thus,they are less able to seek more appropriate healthcare and child-rearing practices [7].Uneducated women may also be less likely to participate in the labor force,utilize effective methods of family planning,and have children who are better nourished and healthier [29].

In conclusion,this study identified that most deaths occur in children under one month and one year,indicating the need for further studies to address under-one mortality.Overall,it appears that differences in maternal factors and accessibility to health care associated with financial burdens increased child mortality risk.Additionally,most components of prenatal and postnatal care had no significant impact on child mortality risk other than intestinal antiparasitic drugs and the absence of maternal vitamin A supplementation within the first two months after giving birth.Although exposure to food groups high in vitamin A and iron was higher in upper-MICs,poor nutrition was observed uniformly across all LMICs.Thus,this study highlights the need to focus on improving access to health care in LMICs and indicates the need for more research to clarify the effects of postpartum vitamin A supplementation on child mortality in at-risk populations.

AcknowledgementsDataset analysed in this study was collected by the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) program.

Author contributionsLK: conceptualization,formal analysis,writing–original draft.CS: visualization,writing–original draft.SJ: supervision,writing–review and editing.

FundingNo funding was obtained for this study.

Data availabilityThe datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interestNo financial or non-financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Ethical approvalOpen dataset from the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) was used,permission was provided to the principal supervisor and all collaborators for use,so no ethics application was required.

World Journal of Pediatrics2023年9期

World Journal of Pediatrics2023年9期

- World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- Fecal microbiota transplantation in childhood: past,present,and future

- Pediatric endocrinopathies related to COVID-19: an update

- Clinical epidemiology and disease burden of bronchiolitis in hospitalized children in China: a national cross-sectional study

- Serum levels of the novel adipokine isthmin-1 are associated with obesity in pubertal boys

- Effects of fentanyl and sucrose on pain in retinopathy examinations with pain scale,near-infrared spectroscopy,and ultrasonography:a randomized trial

- Maternal and neonatal blood vitamin D status and neurodevelopment at 24 months of age: a prospective birth cohort study