Cardiopulmonary prognosis of prophylactic endotracheal intubation in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding undergoing endoscopy

Yufang Lin ,Fei’er Song ,Weiyue Zeng ,Yichi Han ,Xiujuan Chen ,Xuanhui Chen ,Yu Ouyang,Xueke Zhou,4,Guoxiang Zou,Ruirui Wang,Huixian Li,Xin Li

1 School of Biology and Biological Engineering, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou 510006, China

2 Department of Emergency Medicine, Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital, Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences,Guangzhou 510080, China

3 Medical Big Data Center, Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital, Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences,Guangzhou 510080, China

4 School of Medicine, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou 510006, China

5 Guangdong Cardiovascular Institute, Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital, Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences, Guangzhou 510100, China

BACKGROUND: It is controversial whether prophylactic endotracheal intubation (PEI) protects the airway before endoscopy in critically ill patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB).The study aimed to explore the predictive value of PEI for cardiopulmonary outcomes and identify high-risk patients with UGIB undergoing endoscopy.METHODS: Patients undergoing endoscopy for UGIB were retrospectively enrolled in the eICU Collaborative Research Database (eICU-CRD).The composite cardiopulmonary outcomes included aspiration,pneumonia,pulmonary edema,shock or hypotension,cardiac arrest,myocardial infarction,and arrhythmia.The incidence of cardiopulmonary outcomes within 48 h after endoscopy was compared between the PEI and non-PEI groups.Logistic regression analyses and propensity score matching analyses were performed to estimate effects of PEI on cardiopulmonary outcomes.Moreover,restricted cubic spline plots were used to assess for any threshold effects in the association between baseline variables and risk of cardiopulmonary outcomes (yes/no) in the PEI group.RESULTS: A total of 946 patients were divided into the PEI group (108/946,11.4%) and the non-PEI group (838/946,88.6%).After propensity score matching,the PEI group (n=50) had a higher incidence of cardiopulmonary outcomes (58.0% vs.30.3%,P=0.001).PEI was a risk factor for cardiopulmonary outcomes after adjusting for confounders (odds ratio [OR] 3.176,95% confidence interval [95% CI] 1.567-6.438, P=0.001).The subgroup analysis indicated the similar results.A shock index >0.77 was a predictor for cardiopulmonary outcomes in patients undergoing PEI (P=0.015).The probability of cardiopulmonary outcomes in the PEI group depended on the Charlson Comorbidity Index(OR 1.465,95% CI 1.079-1.989,P=0.014) and shock index >0.77 (compared with shock index ≤0.77[OR 2.981,95% CI 1.186-7.492,P=0.020,AUC=0.764]).CONCLUSION: PEI may be associated with cardiopulmonary outcomes in elderly and critically ill patients with UGIB undergoing endoscopy.Furthermore,a shock index greater than 0.77 could be used as a predictor of a worse prognosis in patients undergoing PEI.

KEYWORDS: Prophylactic endotracheal intubation;Upper gastrointestinal bleeding;Cardiopulmonary outcomes;eICU Collaborative Research Database

INTRODUCTION

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is bleeding from the esophagus,stomach,or duodenum,and is the most commonly characterized by black stools or vomiting blood.[1,2]UGIB has an incidence of 47/100000,with a mortality of 2%-10%.[1,3]In critically ill patients,the incidence of UGIB reaches 4.7%,leading to a prolonged length of intensive care unit (ICU) stay of approximately 4-8 d,increased ICU mortality of approximately 1-4 times,and an overall 90-day mortality of 26.2%.[4,5]Endoscopy is an important modality to uncover the etiology of UGIB,and early endoscopy (<24 h) has been proven to be beneficial for patients with UGIB.[2,6-8]Endoscopy is often complicated with cardiopulmonary outcomes,with an incidence of approximately 50%.They mainly included dyspnea,pulmonary edema,hypotension,arrhythmias,myocardial infarction,and cardiac arrest.Although cardiac arrest and acute myocardial infarction are rare,they can be life-threatening when they occur.[9,10]

No difference was observed in the incidence of cardiopulmonary complications,ICU length of stay,or mortality whether UGIB patients received prophylactic endotracheal intubation (PEI) before endoscopy,but PEI was associated with fewer in-hospital cardiac arrests and massive aspiration.[11]In contrast,previous studies showed that PEI or selective intubation prior to upper endoscopy might lead to a higher incidence of pneumonia.[12,13]There is controversy over the protective role of PEI in reducing harmful cardiopulmonary outcomes.[11,14]Therefore,this real-world study aimed to examine the association between PEI and cardiopulmonary outcomes in critically ill patients with UGIB.

METHODS

Study design and participants

This was a retrospective,observational study.Patients who underwent diagnostic/therapeutic endoscopy for UGIB were enrolled in the eICU Collaborative Research Database (eICU-CRD).eICU-CRD is a high-quality public multicenter ICU database that incorporates electronic medical records from 208 hospital ICUs in the USA from 2014 to 2015.[15,16]The study population was critically ill patients diagnosed with UGIB undergoing endoscopy.The definition of PEI mainly includes the following points:no indications for tracheal intubation of the respiratory system or nervous system.The specific manifestation was as follows during intubation: (1) blood oxygen saturation≥90%;(2) respiratory rate 12-30 breaths/min;(3) no significant aspiration;and (4) no acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).The exclusion criteria were as follows:(1) extubation before endoscopy;(2) airway intubation for therapeutic purposes other than airway protection;(3)indications of emergency endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation;and (4) time of airway intubation beyond 48 h prior to endoscopy.

The primary endpoint was the composite cardiopulmonary outcome,including aspiration,pneumonia,pulmonary edema,shock or hypotension,cardiac arrest,myocardial infarction,and arrhythmia occurring within 48 h of endoscopy.[17]The secondary endpoints were in-hospital mortality,hospital length of stay (hospital LOS),ICU length of stay (ICU LOS),post-endoscopy vasopressor use within 48 h,radiology within 48 h,red blood cell infusion within 48 h,and postendoscopy antibiotic use within 48 h. All cardiopulmonary complications before endoscopy were excluded.

Data collection

After gaining access to the database,we used Structured Query Language (SQL) with PostgreSQL(version 9.6 UC Berkeley,USA) to extract demographic and vital signs,treatment,laboratory tests,and relevant past medical history data. Cardiopulmonary outcomes were collected via ICD-9 codes in the eICU-CRD.Baseline variables were extracted at the most recent time before endoscopy.Intervention radiology and red blood cell infusion were identified from the description of the treatment in the eICU-CRD.The ratios of ongoing active hematemesis,agitation,and encephalopathy before endoscopy were described in baseline characteristics,and data extraction was performed by the diagnosis of acute blood loss anemia,encephalopathy,and mental state change (supplementary Table 1).

In the absence of atrial fibrillation,the shock index was calculated using the most recent pulse and systolic blood pressure before endoscopy.[18]Patients whose ages were greater than 89 were substituted with 90.[19]The AIMS65,[20]Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI),[21]and MELD score[22]were calculated to determine the severity of illness and comorbidity in critically ill patients (supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Statistical analysis

The PEI and non-PEI groups were matched 1:2 using propensity score matching.The propensity score was estimated using a logistic regression model adjusted for age,CCI,Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation(APACHE) IV score,Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS),AIMS65 score,history of heart or lung disease,history of cirrhosis,use of sedatives during endoscopy,and use of vasopressor 24 h before endoscopy,and nearest neighbor matching was used(match tolerance=0.2).

Baseline continuous variables were expressed as the mean±standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range)and were compared using the independent samplest-test or Wilcoxon rank sum test regarding the distribution.Categorical variables were expressed as numbers (percentages) and were compared using Fisher’s exact test,Yates’s corrected Chisquare tests,or Pearson’s Chi-square test where appropriate.Logistic regression was performed in population and subgroups to examine the association between PEI and cardiopulmonary outcomes.Subgroups included patients with/without ongoing active hematemesis,agitation,or encephalopathy before endoscopy,and patients with/without a history of cirrhosis.The performance of multivariate logistic regression model was evaluated using area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve.Restricted cubic spline(RCS) functions with three nodes were used to examine the relationship between composite cardiopulmonary outcomes(yes/no) and continuous variables and indicate the objective reference values where odds ratios (ORs) were equal to 1,with aP-value of less than 0.05 to consider the fitted association.Missing data were imputed using the median.All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 22.0;IBM SPSS Inc.,USA),R version 3.6.2 (R Foundation,Austria),and GraphPad Prism (version 8.0.0,GraphPad Software,USA).All probability values were two-tailed,and aP-value <0.05 indicated statistical significance.

RESULTS

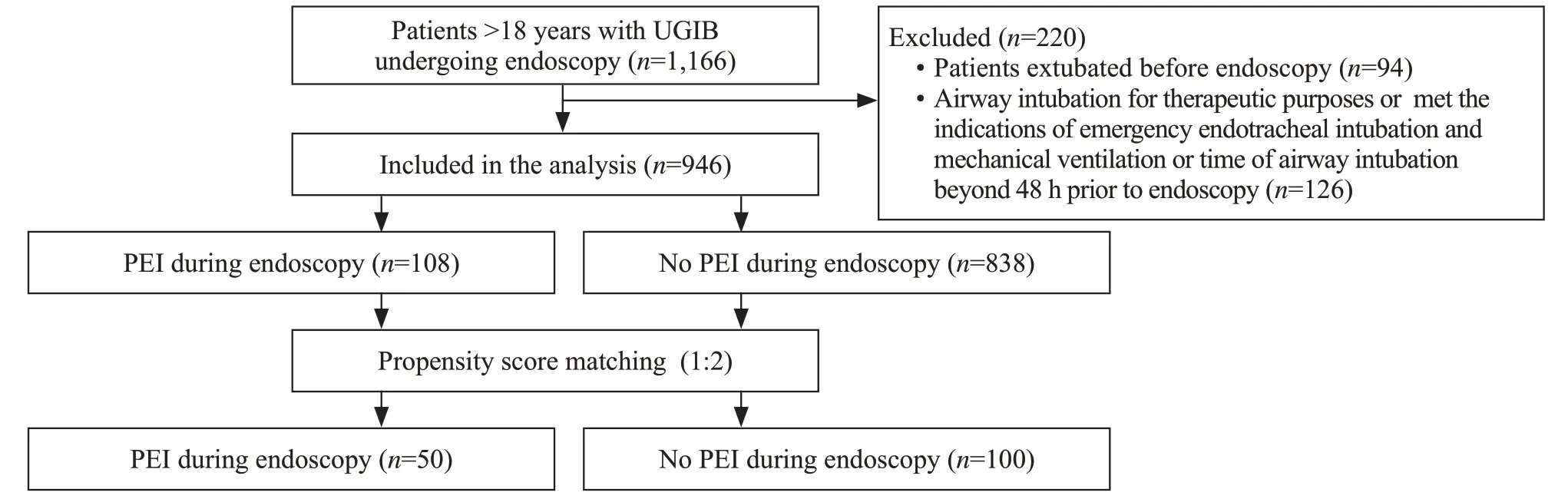

A total of 946 eligible patients were enrolled in the study and 11.4% (108/946) underwent PEI (Figure 1).Compared to non-PEI patients,PEI patients were more likely to be sedated (23.1% vs.7.9%,P<0.001),to receive vasopressors within 24 h prior to the endoscopy (29.6% vs.9.3%,P<0.001),and to receive red blood cells infusion prior to endoscopy (63.0% vs.52.7%,P=0.045).The prevalence of cirrhosis was higher (36.1% vs.20.9%,P<0.001).Also,higher APACHE IV score (79.50 vs.54.00,P<0.001),AIMS65 score (2.00 vs.1.00,P<0.001),MELD score(11.26 vs.7.58,P=0.001),INR (1.30 vs.1.30,P=0.001),total bilirubin (0.80 vs.0.80,P<0.001),and lower systolic blood pressure (113.00 vs.119.00,P=0.029) and GCS(12.00 vs.15.00,P<0.001) were observed in the PEI group.On the contrary,cardiac comorbidity (14.8% vs.24.3%,P=0.027) was more common in non-PEI patients.Baseline characteristics were compared in Table 1.In the PEI group,endoscopy was performed at the median of 6 h after intubation,and 86.1% (93/108) of patients were intubated 24 h after intubation.

After propensity score matching,the baseline variables were essentially similar between the two groups.The mean age of patients in both groups was 64.00 years.Compared to the non-PEI patients,those with PEI had a higher incidence of cardiopulmonary outcomes (58.0% vs.30.3%,P=0.001).The incidence of shock and hypotension (44.0% vs.11.0%,P<0.001),pulmonary edema (6.0% vs.0%,P=0.010),cardiac arrest(6.0% vs.0.0%,P=0.010),and in-hospital mortality(18.0% vs.2.0%,P=0.002) were higher in the PEI group.Additionally,the number of patients receiving vasopressors (22.0% vs.10.0%,P=0.046) and the number of patients receiving red blood cell infusion (62.0% vs.44.0%,P=0.038) was higher in the PEI group.Moreover,the ICU LOS (3.57 d vs.1.90 d,P<0.001) and the hospital LOS (9.71 d vs.5.50 d,P=0.001) were longer in the PEI group (Table 2).

Univariate logistic regression analysis showed that patients undergoing PEI had a 2.6-fold higher risk of cardiopulmonary outcomes than those in the non-PEI group (OR2.659,95% confidence interval [95%CI]1.772-3.990,P<0.001).After matching for age,the CCI,APACHE IV score,GCS,AIMS65 score,history of heart or lung disease,history of cirrhosis,use of sedative during endoscopy,and use of vasopressors 24 h before endoscopy,the predictive value of PEI persisted(OR3.176,95%CI1.567-6.438,P=0.001) (Table 3).In addition,analysis of the subgroups with no or only ongoing active hematemesis,agitation,or encephalopathy before endoscopy suggested that the likelihood of cardiopulmonary outcomes was 2.130 times (OR2.130,95%CI1.328-3.418,P=0.002) higher in the PEI group and 5.597 times (OR5.597,95%CI2.153-14.547,P<0.001) higher in the non-PEI group.Further analysis of patients with or without a history of cirrhosis showed that the likelihood of cardiopulmonary outcomes was 3.987 times (OR3.987,95%CI1.861-8.542,P<0.001) higher in the PEI group and 2.909 times (OR2.909,95%CI1.752-4.829,P<0.001) higher in the non-PEI group.

Figure 1.Patient selection f lowchart.PEI: prophylactic endotracheal intubation;UGIB: upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Restricted cubic spline plots were used to flexibly determine the relationship between clinical risk factors and cardiopulmonary outcomes (Figure 2).In patients undergoing PEI,the shock index was associated with cardiopulmonary outcomes (P<0.05),with a nadir of 0.77.

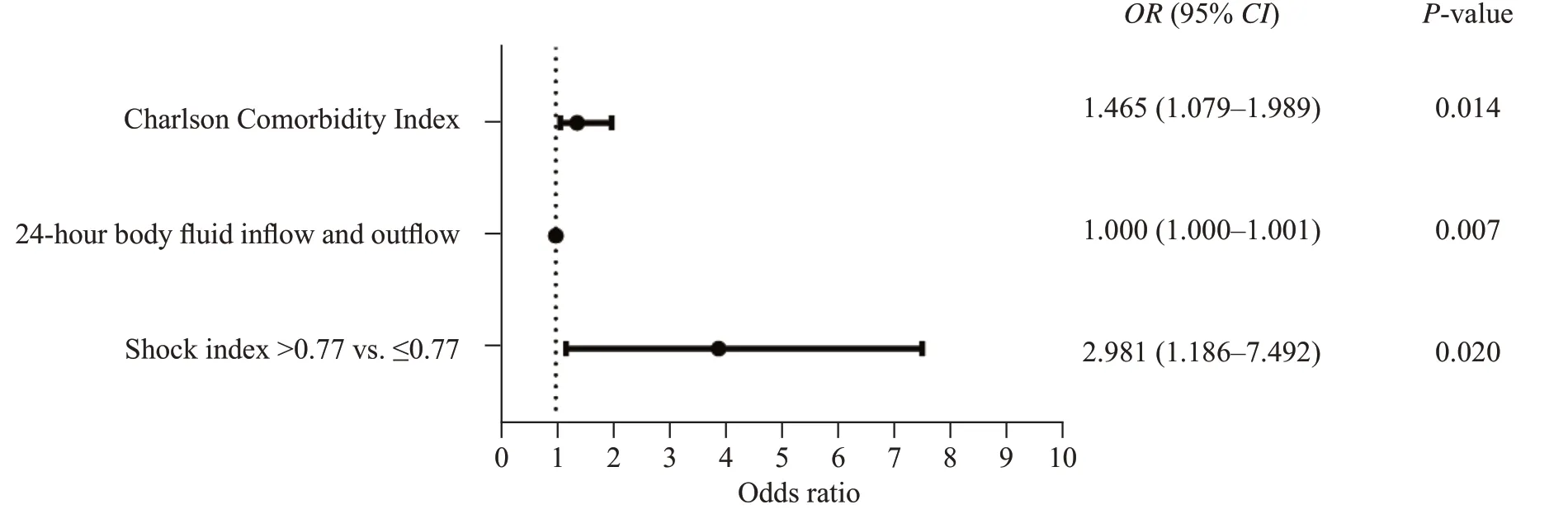

In Figure 3,the multivariable logistic analysisshowed that cardiopulmonary outcomes after endoscopy were strongly correlated with the CCI (OR1.465,95%CI1.079-1.989,P=0.014) and the shock index >0.77(compared with shock index ≤0.77 [OR2.981,95%CI1.186-7.492,P=0.020,AUC=0.764]).

DISCUSSION

This study is a real-world study of the relationship between PEI and cardiopulmonary outcomes after endoscopy in elderly and critically ill patients with UGIB.Approximately 32.2% (305/946) of critically ill patients with UGIB developed cardiopulmonary outcomes after endoscopy.Patients who underwent PEI had more cardiopulmonary outcomes,more use of vasopressor after endoscopy,longer hospital LOS,longer ICU LOS,and higher in-hospital mortality.PEI is associated with a higher risk of cardiopulmonary outcomes in patients with UGIB.It is well known that patients with cirrhosis develop complications from the heart and lungs more often than the non-cirrhotic population.Considering the complications in cirrhotic patients due to the natural course of the disease,we conducted a subgroup analysis for cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients to evaluate the association between cardiopulmonary outcomes and PEI.In addition,the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) only recommends intubation in very particular situations,such as ongoing active hematemesis,agitation,or encephalopathy with the inability to adequately control the airway.[23]With this in mind,we performed the same subgroup analysis.This association was consistent across multiple subgroup analyses,and it further illustrates that PEI is associated with a high risk of cardiopulmonary outcomes in patients with UGIB.In patients undergoing PEI,a shock index greater than 0.77 served as a predictor of cardiopulmonary outcomes.

A case-control study by Rehman et al[14]in 2009 thatincluded 307 critically ill patients with UGIB found no significant difference in cardiopulmonary outcomes between patients who received PEI and those who were not intubated,based on a composite of outcomes including pneumonia,pulmonary edema,myocardial infarction,ARDS,and cardiac arrest.It should be noted that the previous study did not report on the comorbidity of respiratory distress prior to intubation and was not adjusted for mental status or bleeding status.Mental status and bleeding status were adjusted in our study by GCS and AIMS65 score.The AIMS65 score is used to predict in-hospital mortality in patients with UGIB and has the advantages of being easy to calculate,highly accurate,and independent of ill-defined medical history criteria.[20]The GCS is critical in the assessment of consciousness in critically ill patients,as well as in the management of the entire clinical process.[23]Hayat et al[17]demonstrated that the overall incidence of cardiopulmonary outcomes in UGIB patients with a mean age of 59 years who received PEI and those who were not intubated was 13.0% after matching.The incidence of cardiopulmonary outcomes in our study was higher than that in the previous study (58.0% in the PEI group and 30.3% in the non-PEI group).One of the underlying reasons was that the median age of the patients in our study was older (64 years),and cardiopulmonary outcomes after endoscopy mainly occur in elderly patients.[24]All patients in the study by Hayat et al[17]underwent endoscopy within 24 h after admission,while the present study included patients who underwent endoscopy within 48 h,with a median duration of 16.7 h,and 69.7% (659/946) of patients completed endoscopy within 24 h after admission.However,it should be noted that patients in the present study had shock or hypotension(98/287,34.1%),massive blood loss (116/287,40.4%),and altered mental status (55/287,19.2%) after admission,which might be the reason for not completing endoscopy within 24 h due to resusitation.In fact,because tracheal intubation and endoscopy are performed sequentially and ideally performed immediately after each other in clinical practice,complications of PEI should theoretically include complications of tracheal intubation and complications of endoscopy,which are often difficult to distinguish.It is reasonable that our observation of complications in the first 48 h after endoscopy captures the combined effects of this procedure.

Table 3.Association between cardiopulmonary outcomes and PEI

Figure 3.Multivariable logistical analysis of cardiopulmonary outcomes in patients undergoing prophylactic endotracheal intubation.

The primary outcome of the study was adverse cardiopulmonary events after endoscopy,excluding adverse events before endoscopy.After propensity score matched,the observed difference between the two groups was whether PEI was performed.The discussion of the possible adverse factors of PEI is also consistent with previous literature reports and our clinical knowledge.One of the objectives of this study is to determine why PEI does not achieve the desired conservation purpose and to suggest possible complementary measures to make PEI more effective.

Among the 108 patients in the PEI group,the shock index was associated with cardiopulmonary outcomes,with a cutoffvalue of greater than 0.77 in patients who underwent PEI.Previous literature has shown that hemodynamic collapse is a common complication after endotracheal intubation.[25]The shock index was effective in evaluating hemodynamics with a normal range between 0.5 and 0.7.[26]In a retrospective cohort study conducted by Trivedi et al[27]in 2015,a pre-intubation shock index greater than 0.9 was identified as a risk factor for post-intubation hypotension and ICU mortality in adult intensive care patients.This suggested that hemodynamic instability,as indicated by an elevated shock index,might serve as a possible index of poor outcomes in intubated patients.Regarding patients with UGIB who underwent PEI before endoscopy,few practical predictors for cardiopulmonary outcomes have been recognized.We proposed a shock index greater than 0.77 as a possible predictor of cardiopulmonary outcomes after PEI.

The present study had several limitations.First,patients who were not intubated were classified as non-PEI because it was impossible to exclude patients with a contradiction of intubation.Second,because of the retrospective design of our study,we cannot determine the reason for intubation or whether intubation directly led to the observed outcomes.Third,our data are from the year of 2014 to 2015 and may have aging issues.Finally,because of the observational study design,only associations can be inferred,not causality.Meanwhile,the association of endoscopy with cardiopulmonary outcomes could not be demonstrated.Nevertheless,the present study was a real-world study that stemmed from a large-scale database.The current finding requires further validation in prospective studies.

CONCLUSION

The present study provides clinical evidence for airway protection in patients undergoing endoscopy.The study demonstrated that PEI was associated with cardiopulmonary outcomes in elderly and critically ill patients with UGIB undergoing endoscopy.Furthermore,a shock index greater than 0.77 could be used as a predictor of a worse prognosis in patients undergoing PEI.

Funding:This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China(2020AAA0109605),the National Natural Science Grant of China(82072225,82272246),High-level Hospital Construction Project of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital (DFJHBF202104),Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (202206010044),and Leading Medical Talents in Guangdong Province of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital (KJ012019425).

Ethical approval:This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital(KY2023-021-01).

Conf licts of interest:The authors do not have a financial interest or relationship to disclose regarding this research.

Contributors:YFL,FES,and WYZ contributed equally to this work.YFL,YCH,XL and XYC conceived and designed the experiments.YFL,XHC,and HXL collected and analyzed the data.YOY,FES,GXZ and WYZ contributed to the writing of the manuscript.FES,WYZ,RRW,and XKZ revised the manuscript.All authors approved the final version.

All the supplementary files are available at http://wjem.com.cn.

World journal of emergency medicine2023年5期

World journal of emergency medicine2023年5期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Emergency department approach to monkeypox

- The neuro-prognostic value of the ion shift index in cardiac arrest patients following extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- A prospective cohort study on serum A20 as a prognostic biomarker of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Mendelian randomization study to investigate the causal relationship between plasma homocysteine and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Effects of mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor on sepsis-associated acute kidney injury

- Synchronized ventilation during resuscitation in pigs does not necessitate high inspiratory pressures to provide adequate oxygenation