Laparoscopic liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma complicated with significant portal hypertension: A propensity score-matched survival analysis

Zhang-You Guo , Yuan Hong , Bing Tu , Yao Cheng , Xiao-Mei Wang , *

a Department of Minimally Invasive Interventional Therapy, Yunnan Cancer Hospital, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Yunnan Cancer Center, Kunming 650118, China

b Medical Laboratory, The First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Institute of Experimental Diagnostics of Yunnan Province, Key Laboratory of Laboratory Medicine of Yunnan Province, Kunming 650032, China

c Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing 40 0 010, China

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma

ABSTRACT Background: Significant portal hypertension (SPH) is a relative contraindication for patients with resectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).However, increasing evidence indicates that liver resection is feasible for HCC patients with SPH.Methods: HCC patients with cirrhosis who underwent laparoscopic liver resection (LLR) in two centers from January 2013 to April 2018 were included.Surgical and survival outcomes were analyzed to explore potential prognostic factors.Propensity score matching (PSM) analysis was performed to minimize bias.Results: A total of 165 patients were divided into two groups based on the presence (SPH, n = 76) or absence (non-SPH, n = 89) of SPH.Patients in the SPH group had longer operative time, more blood loss,and more advanced TNM stage than patients in the non-SPH group ( P < 0.05).However, there were no significant differences in the postoperative 90-day mortality rate ( n = 0), overall postoperative complications (47.4% vs.41.6%, P = 0.455), Clavien-Dindo classification ( P = 0.347), conversion to open surgery(9.2% vs.6.7%, P = 0.557), or length of hospitalization (16 vs.15 days, P = 0.203) between the SPH and non-SPH groups before PSM.Similar results were obtained after PSM.The 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival rates in the SPH group were not significantly different from those in the non-SPH group both before and after PSM (log-rank P > 0.05).After PSM, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)≥400 μg/L [hazard ratio (HR) = 4.71, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.69-8.25], ascites (HR = 2.18, 95%CI: 1.30-3.66), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification (III vs.II) (HR = 2.13, 95% CI:1.11-4.07) and tumor diameter > 5 cm (HR = 3.91, 95% CI: 2.02-7.56) independently predicted worse OS.Conclusions: LLR for patients with HCC complicated with SPH appears feasible at the price of increasing operative time and blood loss.AFP, ascites, ASA classification and tumor diameter may predict the prognosis of HCC complicated with SPH after LLR.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer and the third leading cause of death from cancer worldwide [1].HCC ranks third in prevalence and second in mortality among cancers in China [2].Approximately 80%-90% of HCC patients in China have liver cirrhosis, and liver cirrhosis is the main cause of significant portal hypertension (SPH) [2].

Both the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL)clinical practice guidelines for HCC and the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) guidelines indicate that HCC patients with SPH are not suitable for liver resection [3].However, in recent years, reports of liver resection for HCC patients with SPH have been increasing.Ishizawa et al.[4]reported that the 5-year survival rate of HCC patients with SPH and good liver function (Child-Pugh grade A) can reach 56%.Lopez-Lopez et al.[5]reported a 5-year overallsurvival (OS) of 63.4% when laparoscopic liver resection (LLR) was performed in Child-Pugh A cirrhotic patients with HCC, who had undergone preoperative transcatheter arterial chemoembolization(TACE).However, they did not find significant differences in survival outcomes between SPH group and non-SPH group.Cucchetti et al.[6]compared 89 HCC patients with SPH and 152 without SPH who underwent open liver resection and reported no significant difference in surgical complications and OS between the two groups, with 5-year OS rates of 56.3% and 61.4%, respectively.Some new studies have provided evidence that LLR is not only safe in treating HCC patients with SPH but also enables HCC patients with SPH to achieve good long-term survival [ 5 , 7 , 8 ].Recent studies have rendered the EASL and BCLC guidelines on liver resection for HCC patients with SPH obsolete.

The objective of this study was to assess the safety and effectiveness of LLR for HCC patients complicated with SPH and explore the potential factors for HCC prognosis.We compared the surgical and survival outcomes of HCC patients complicated with SPH and those without SPH who underwent LLR.

Methods

Patients

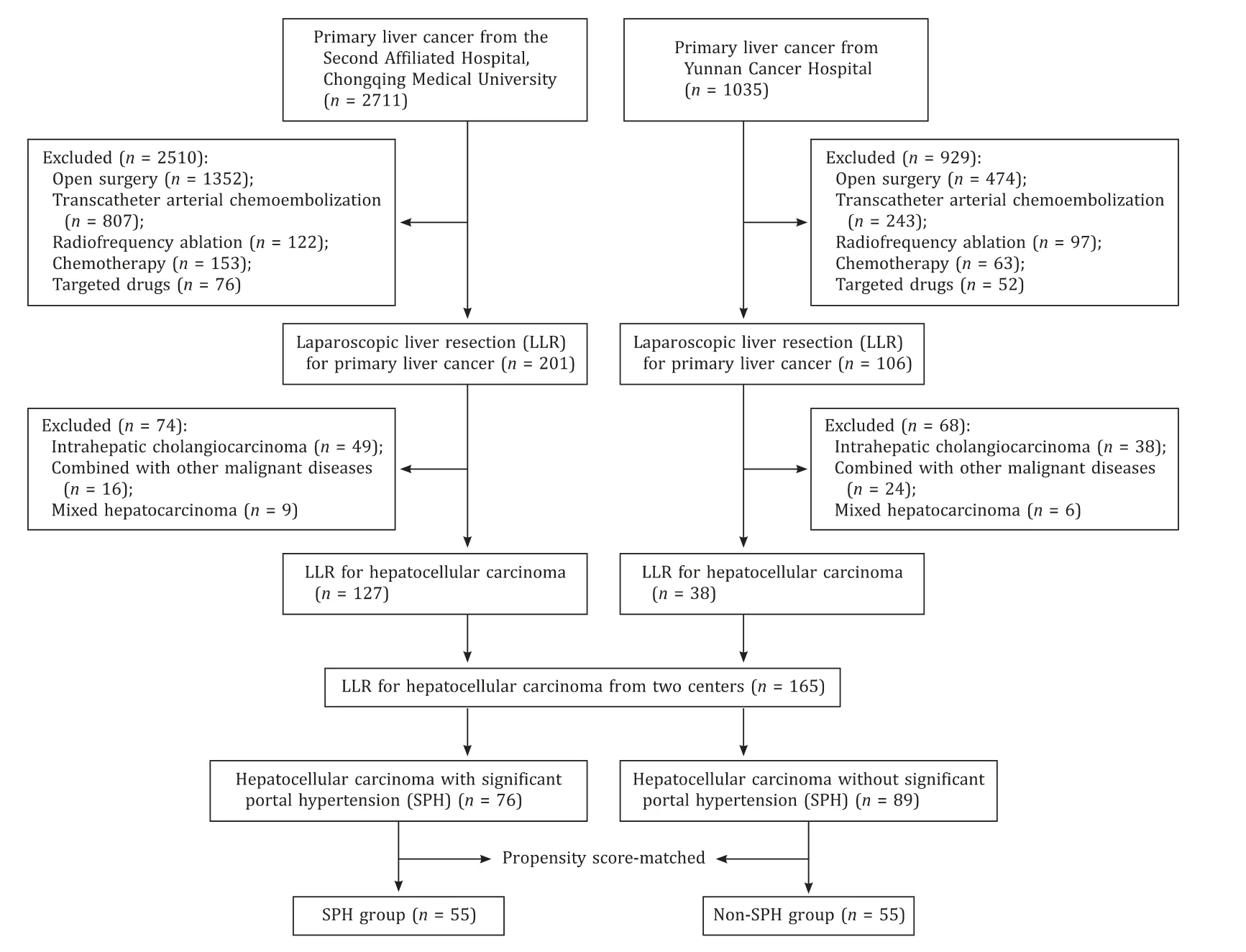

This study was conducted according to the guidelines in theDeclarationofHelsinki, and all procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital, Chongqing Medical University (2019-60).Because of the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent was waived.A total of 165 HCC patients (127 treated at the Second Affiliated Hospital, Chongqing Medical University and 38 treated at Yunnan Cancer Hospital)from January 2013 to April 2018 were enrolled.The detailed patient screening process of two centers is shown in Fig.1.The research process adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Cohort Studies in Surgery (STROCSS) criteria [9].The study was registered on the ChiCTR Registry (ChiCTR190 0 028315).

Fig.1.Flowchart of patients screen process.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) HCC diagnosed by histopathology or by imaging, according to the EASL guideline [3];(ii) liver cirrhosis diagnosed according to liver biopsy [10]; (iii)patients who were suitable for undergoing LLR; (iv) Child-Pugh A or B.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) postoperative pathology confirmed no HCC; (ii) HCC combined with other types of tumors; (iii) HCC could not be resected radically; (iv) TACE, immunotherapy, radiofrequency ablation, chemotherapy, etc.were performed before LLR; (v) Child-Pugh C; (vi) patients with severe heart, brain, or lung insufficiency before LLR; (vii) patients with portal vein tumor thrombus; (viii) patients with SPH due to causes other than liver cirrhosis.

Diagnosis and classification

SPH was defined as hepatic venouspressure gradient(HVPG) ≥ 10 mmHg.However, HVPG measurement is invasive and cannot be obtained for all patients in this retrospective study.Therefore, researchers adopted to meet the standard surrogate criteria, includingthe presence of gastroesophageal varices(GEV) or platelet count<100 × 109/Lwithspleendiameter>12 cm [1 1, 1 2 ].

The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and surgical images of an HCC patient complicated with SPH are shown in Fig.2 and Fig.3.Postoperative complications were sorted according to the Clavien-Dindo classification [13].Grade I: wound infection; gradeII: postoperative bleeding requiring blood transfusion, gastroparesis requiring total parenteral nutrition; grade III: requiring surgical, endoscopic or radiological intervention, including bile leakage requiring puncture and drainage, postoperative bleeding requiring intervention or surgery to be hemostasis, etc.; grade IV:life-threatening complications (including central nervous system complications) requiring intensive care units (ICU) management,including hemorrhagic shock, single organ dysfunction (including postoperative liver failure and dialysis), and multiorgan dysfunction.

Fig.2.Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis complicated with significant portal hypertension: hepatocellular carcinoma shows typical hypointense on T1-weighted images ( A ), increased contrast enhancement in arterial phase ( B ), and contrast washout during portal venous phase ( C ).

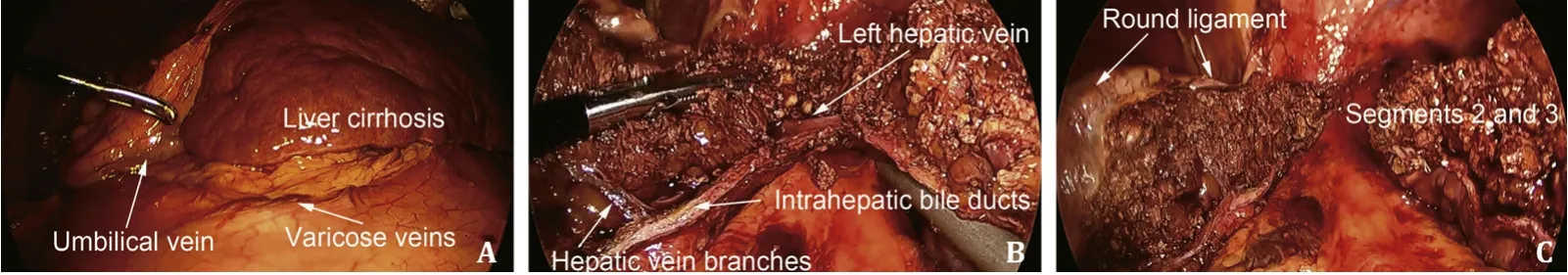

Fig.3.Surgical images of a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis complicated with significant portal hypertension: typical manifestation of liver cirrhosis and significant portal hypertension ( A ); anatomical hepatectomy of segments 2 and 3 ( B and C ).

Postoperative liver failure was identified using the “50-50 criteria”, the association of prothrombin time<50% and serum bilirubin>50μmol/L on postoperative day five [14].

Follow-up

All patients were followed up to death or February, 2020.After discharge, we followed each patient as an outpatient with a computed tomography (CT) scan or MRI and serum tumor marker measurement every three months for the first two years and every six months thereafter.The postoperative 90-day mortality rate was defined as any operation-related death in the first 90 days after surgery.OS was defined as the duration from LLR to the date of death, and recurrence-free survival (RFS) was defined as the duration from LLR to the date of the first recurrence confirmed by imaging examination.

Propensity score matching (PSM)

To overcome the imbalance of the variables of the two groups,we performed PSM to adjust for biases in baseline covariates between the two groups [15].The logistic regression model was established with age, model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score,alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), ascites, albumin, and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) as dependent variables.Patients with similar propensity scores in the two groups were matched (adopting one-to-one nearest-neighbor matching without replacement) using a caliper of 0.2 standard deviation (SD) of the logit of the propensity score.

Statistical analysis

The normality of variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test.The homogeneity of variances was tested using the Levene method.Continuous variables that conformed to normal distribution were expressed as mean ± SD, and comparisons between groups were performed using the unpaired Student’st-test.Continuous variables that did not conform to normal distribution were expressed as median (interquartile range, IQR), and comparisons between groups were performed using the Mann-WhitneyUtest.Categorical variables were described as the number of cases (percentage) and compared using Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test.Kaplan-Meier method was used to calculate survival rates and plot time-to-event curves.The log-rank test was used to compare differences in OS and RFS between the two groups.The Cox regression model was used for multivariate analyses of the variables ofP<0.05 in univariate analysis.All calculations were performed using Stata/SE (version 15.0; Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA) and R software (version 3.6.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing,Vienna, Austria) (“nonrandom” package was used to perform PSM,and “survminer” package and “survival” package were used to perform survival analyses).A two-sided value ofP<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Preoperative characteristics

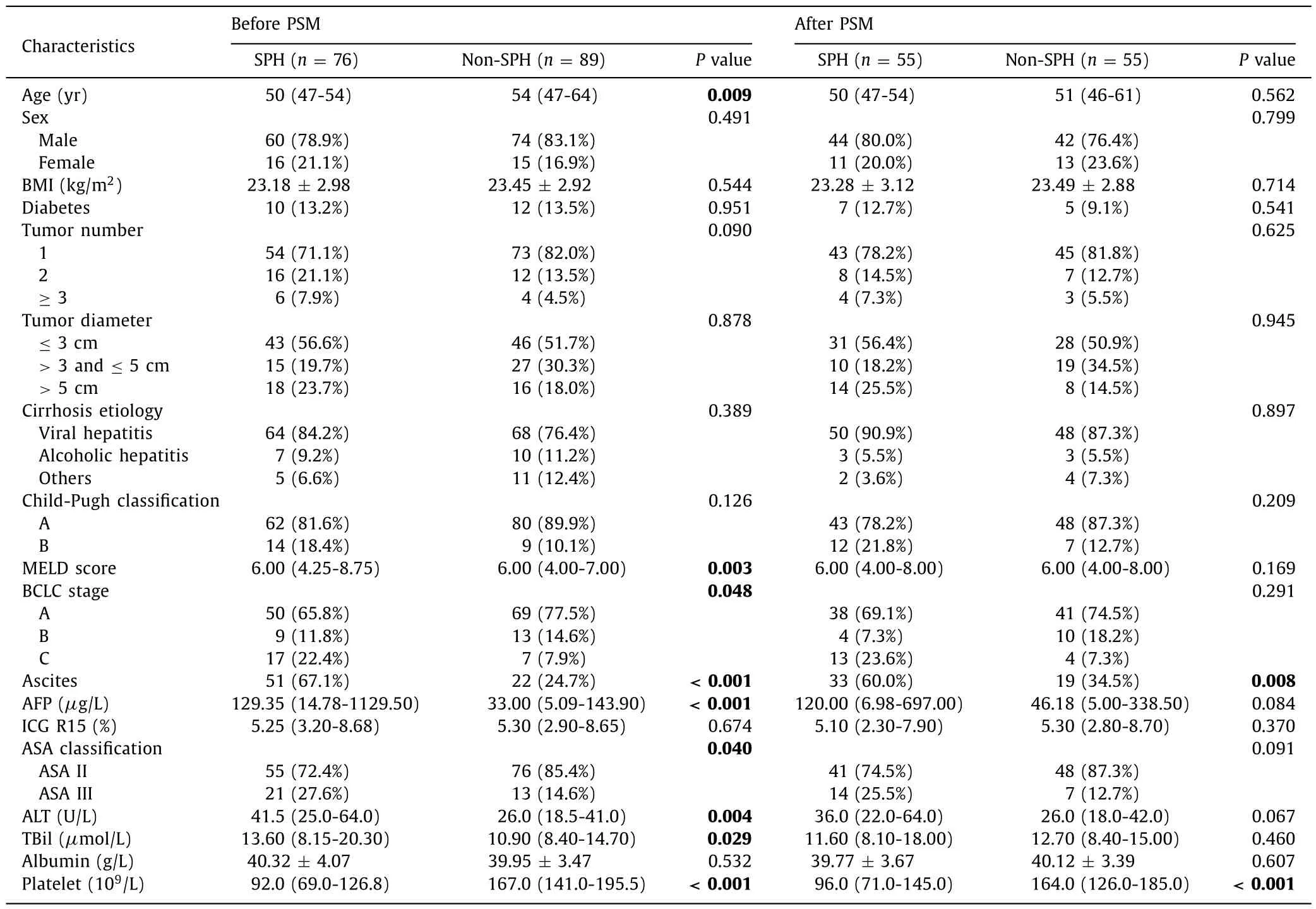

The baseline characteristics of all patients are shown in Table 1.Patients (n= 165) were divided into the SPH group of 76 patients(60 males and 16 females) with a median age of 50 (47-54) years and the non-SPH group of 89 patients (74 males and 15 females)with a median age of 54 (47-64) years.Before PSM adjustment,age, MELD scores, ascites, AFP concentration, BCLC stage, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA), ALT, total bilirubin, and platelets were significantly different between the two groups (P<0.05).After PSM adjustment, the covariates between the two groups no longer differed, except for platelets and ascites.

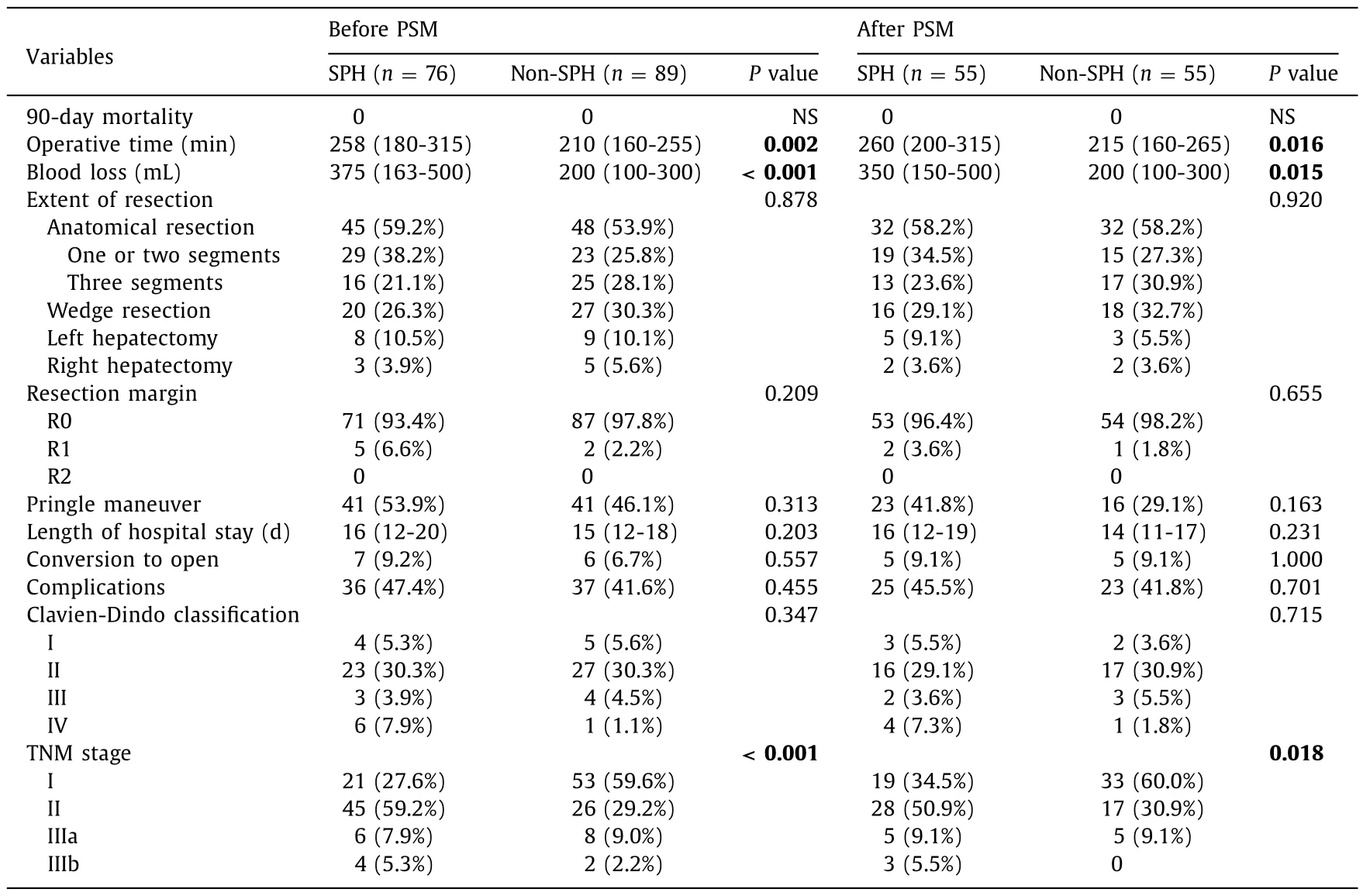

Surgical outcomes and complications

The intraoperative and postoperative results are shown in Table 2.The postoperative 90-day mortality rate was nil in both groups.Regardless of whether PSM was adjusted, the operative time and blood loss were increased in the SPH group compared with those in the non-SPH group (P<0.05).The TNM stage in the SPH group was more advanced than that in the non-SPH group(P<0.05), in which the main differences were TNM stage I and TNM stage II.The main types of liver resection were anatomical hepatectomy and wedge resection, and the extent of liver resection was similar in the two groups (P>0.05).

Table.1Baseline characteristics between SPH group and non-SPH group.

In the SPH group, 45 (59.2%) patients underwent anatomical hepatectomy, 11 (14.4%) patients underwent hemihepatectomy, and 7 (9.2%) patients were converted to open surgery; the Pringle maneuver was performed in 41 (53.9%) patients, 71 (93.4%) patients were confirmed by postoperative pathology to have no invasion of the margin (R0), and 36 (47.4%) had postoperative complications,of which 27 (35.5%) were Clavien-Dindo I/II and 9 (11.8%) were Clavien-Dindo III/IV.In the non-SPH group, 48 (53.9%) patients underwent anatomical hepatectomy, 14 (15.7%) patients underwent hemihepatectomy, and 6 (6.7%) patients were converted to open surgery; the Pringle maneuver was performed in 41 (46.1%) patients, 87 (97.8%) patients were confirmed by postoperative pathology to have no invasion of the margin (R0), and 37 (41.6%) had postoperative complications, of which 32 (36.0%) were Clavien-Dindo I/II and 5 (5.6%) were Clavien-Dindo III/IV, and the differences between the two groups were not significant (P>0.05).Similar results were obtained after PSM adjustment (P>0.05).

Long-term outcomes

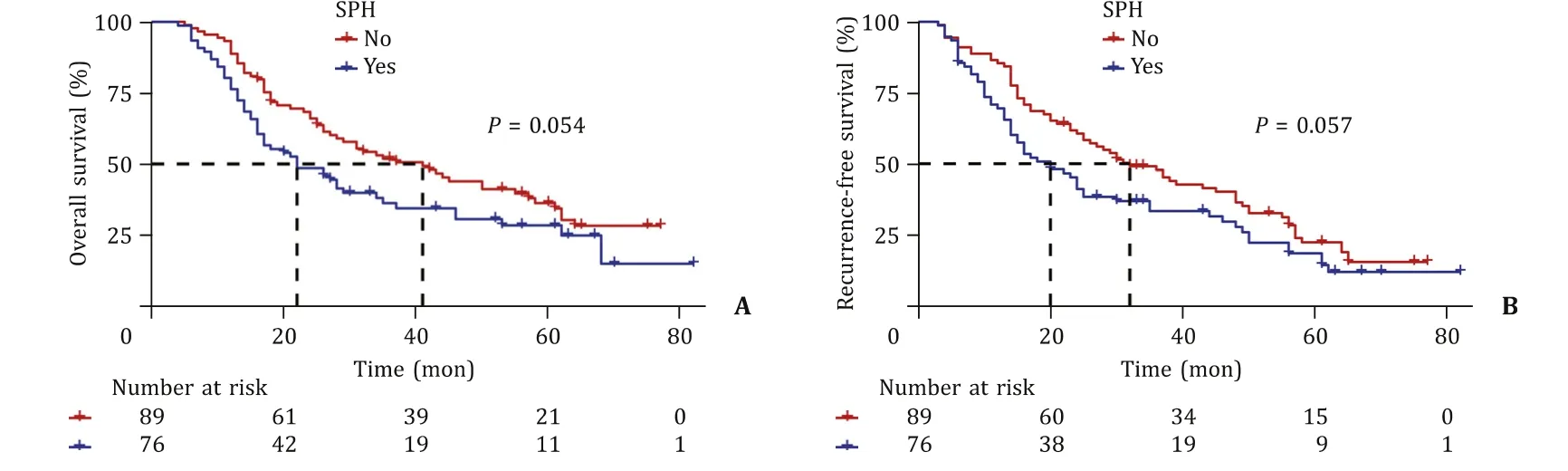

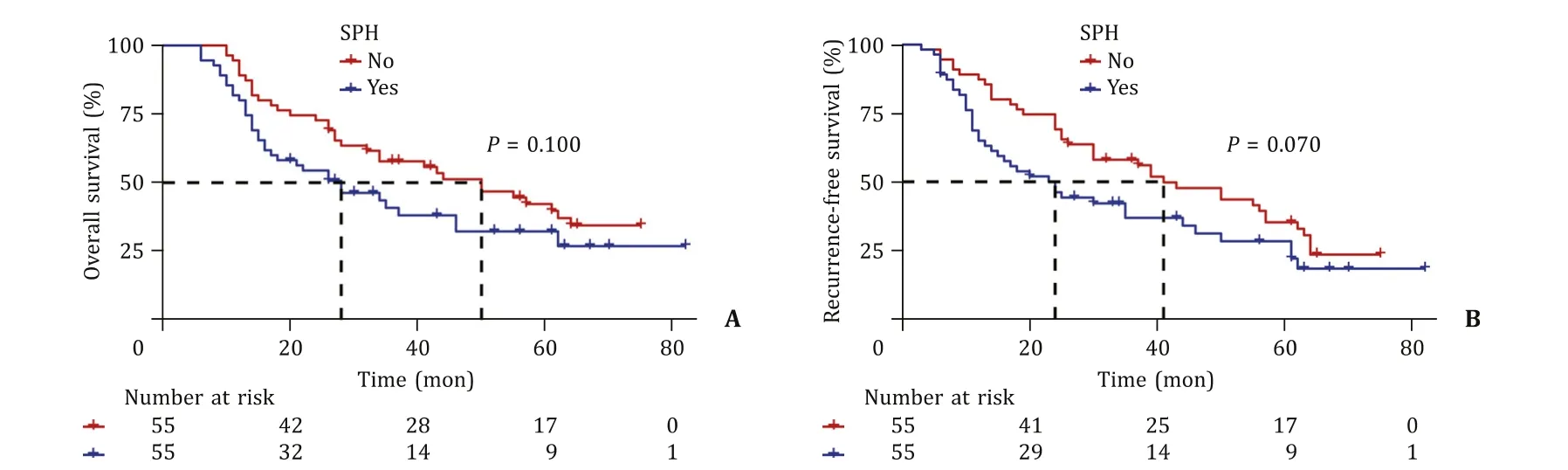

Before PSM, the median follow-up time of the overall population was 61 months, and the median survival time of the overall population was 29 months.The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS and RFS rates in the SPH group were 80.3%, 36.2%, 30.6%, and 69.5%, 33.5%,18.6%, respectively.The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS and RFS rates in the non-SPH group were 93.3%, 51.8%, 36.2%, and 85.4%, 49.6%, 22.5%,respectively.The differences in median OS (22 vs.41 months,P= 0.054) and RFS (20 vs.32 months,P= 0.057) were not statistically significant ( Fig.4 ).After PSM, the results were in line with those before PSM (OS,P= 0.100; RFS,P= 0.070) ( Fig.5 ).

Fig.4.Overall survival ( A ) and recurrence-free survival ( B ) of the significant portal hypertension (SPH) group and the non-SPH group before propensity score-matching.

Fig.5.Overall survival ( A ) and recurrence-free survival ( B ) of the significant portal hypertension (SPH) group and the non-SPH group after propensity score-matching.

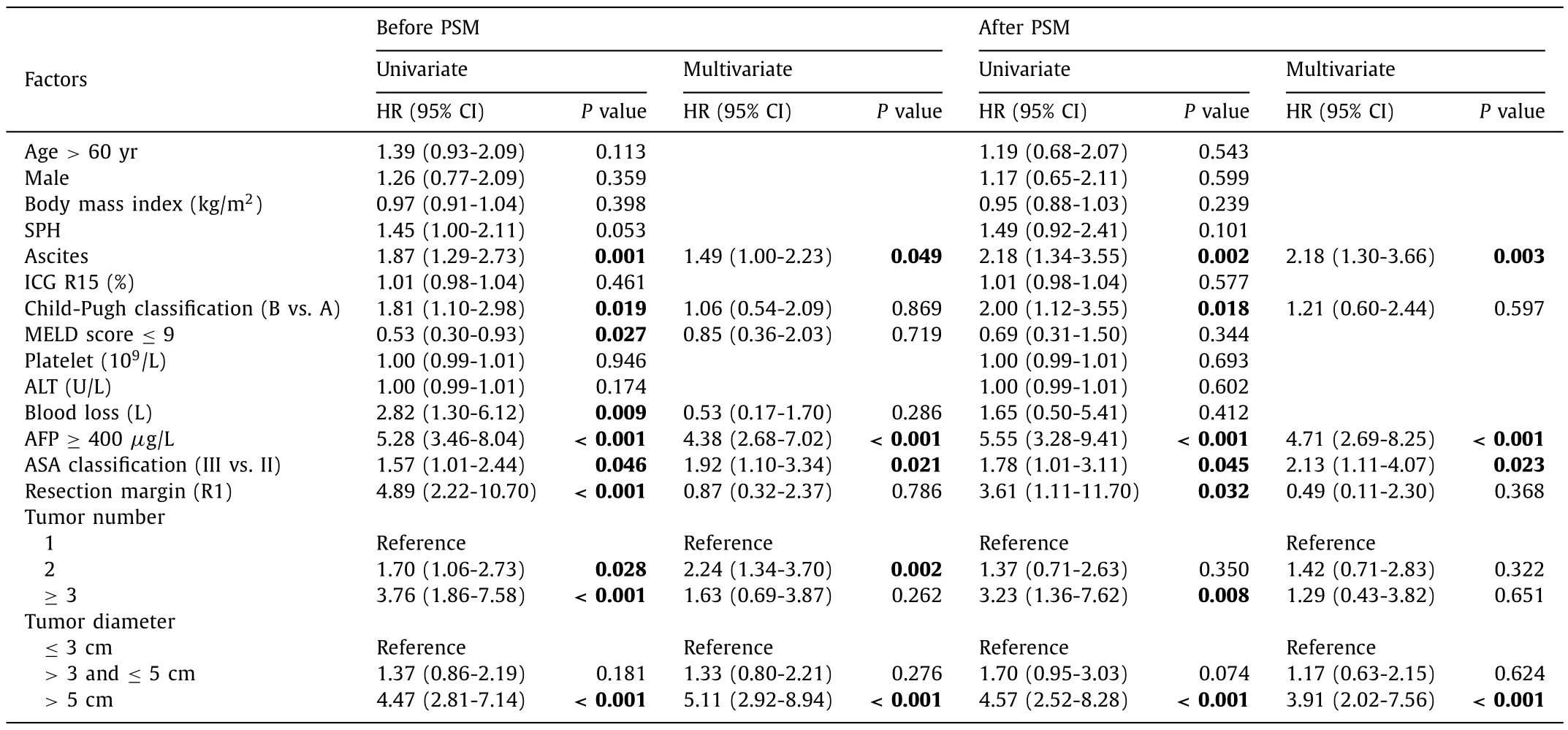

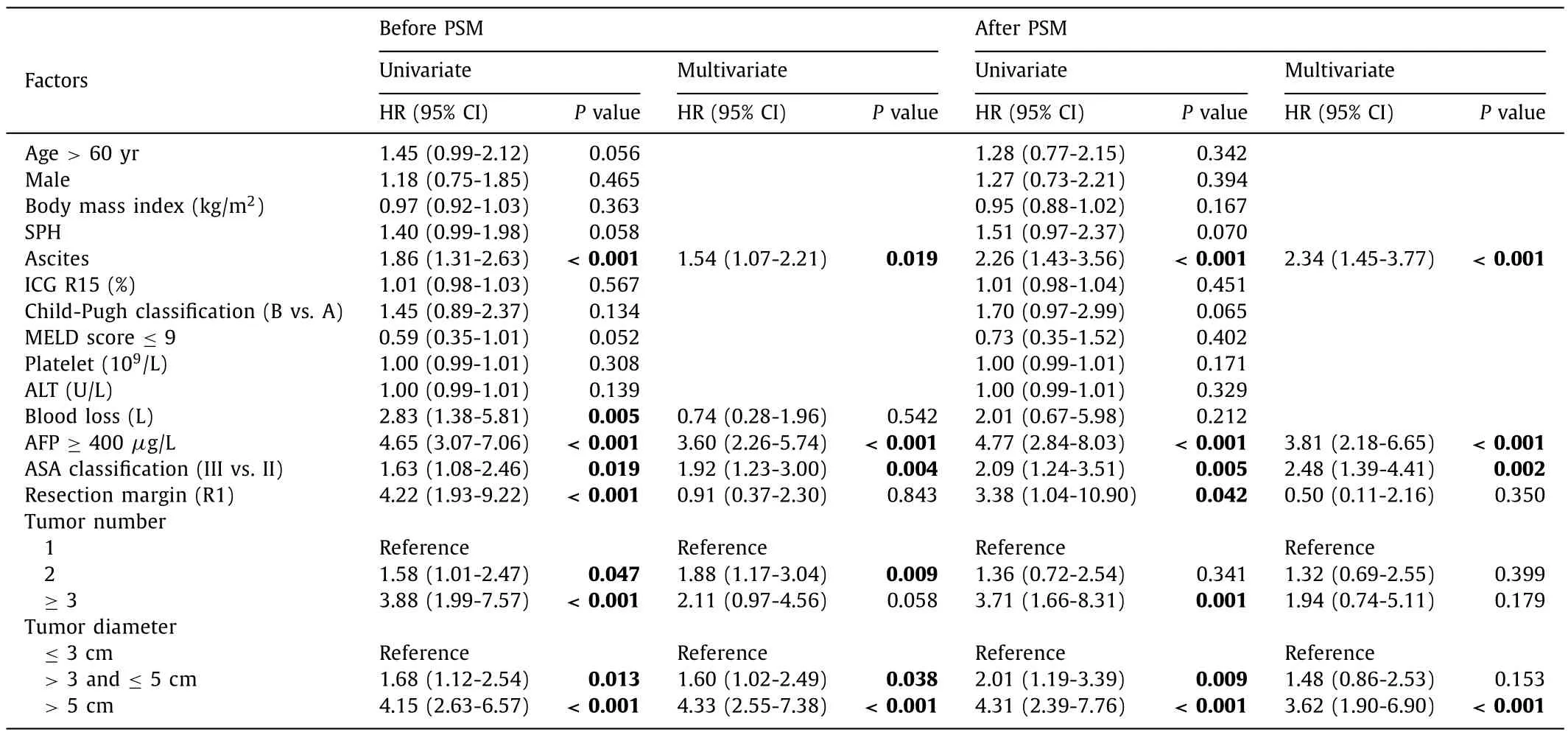

The univariate Cox regression model was used to screen variables that had significant effects on OS and RFS.The Cox regression model analysis results are shown in Tables 3 and 4.After PSM adjustment, multivariate Cox regression model results indicated that AFP ≥400μg/L [hazard ratio (HR) = 4.71, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.69-8.25], ascites (HR = 2.18, 95% CI: 1.30-3.66), ASA (III vs.II) (HR = 2.13, 95% CI: 1.11-4.07) and tumor diameter>5 cm(HR = 3.91, 95% CI: 2.02-7.56) independently predicted worse OS.AFP ≥400μg/L (HR = 3.81, 95% CI: 2.18-6.65), ascites (HR = 2.34,95% CI: 1.45-3.77), ASA (III vs.II) (HR = 2.48, 95% CI: 1.39-4.41)and tumor diameter>5 cm (HR = 3.62, 95% CI: 1.90-6.90) also independently predicted worse RFS.

In light of the previous univariate and multivariate Cox regression model analyses, we divided 165 patients into two groups based on AFP (AFP ≥400μg/L or AFP<400μg/L), ascites (ascites and no ascites), ASA (ASA II and ASA III) or tumor diameter(tumor diameter ≤5 cm and tumor diameter>5 cm).The results suggested that patients with AFP<400μg/L (OS,P<0.001;RFS,P<0.001), no ascites (OS,P<0.001; RFS,P<0.001), ASA II(compared to ASA III: OS,P= 0.044; RFS,P= 0.018) and tumor diameter ≤5 cm (OS,P<0.001; RFS,P<0.001) had better OS and RFS (Fig.S1).

Table.2Univariate analysis of intraoperative and postoperative outcomes.

Discussion

According to the EASL guidelines and BCLC guidelines, SPH is a contraindication for surgical resection of HCC [ 3 , 16 ].Some metaanalyses confirmed that the presence of SPH negatively impacts the postoperative outcome of patients with compensated cirrhosis undergoing liver resection [ 11 , 17 , 18 ].Currently, liver transplantation is undoubtedly the best treatment option for HCC patients complicated with cirrhosis and SPH.However, liver transplantation has the problems of limited donors, high cost, and long waiting time [19].Therefore, for patients with early-onset portal hypertension with cirrhosis and HCC, exploring other strategies to improve their prognosis is now attracting increasing attention [20].The guidelines recommend that such patients can also receive radiofrequency ablation.Compared with radiofrequency ablation, surgical resection can obtain pathological data, such as microvascular invasion, which can predict recurrence well and divide patients into high-risk and low-risk groups.This allows better use of the limited organs available for transplantation [21].Moreover, surgical resection provides better results for patients with tumors larger than 2 cm than radiofrequency ablation [ 22 , 23 ].

Table.3Univariate and multivariate Cox regression model analyses of overall survival.

Table.4Univariate and multivariate Cox regression model analyses of recurrence-free survival.

The general preoperative condition of the two groups was not significantly different.However, the liver function in the SPH group was slightly worse than that in the non-SPH group, as the platelets and ascites in the two groups still differed after PSM, which were closely related to the presence of SPH.Our study found that the presence of SPH and relatively poor liver function did not affect the surgical and survival outcomes of HCC patients complicated with SPH.Both before and after PSM adjustment, operative time and intraoperative blood loss were higher in the SPH group than those in the non-SPH group, which may be related to the high portal venous pressure and rich peripheral collateral circulation formation in SPH patients.Because of the relatively poor liver function in the SPH group, the intraoperative duration of a single hepatic inflow occlusion was reduced, and the number of occlusions was increased, which may also have contributed to the relative increase in intraoperative bleeding and prolonged operative time in the SPH group.Lopez-Lopez et al.[5]reported that performing TACE before LLR can reduce intraoperative bleeding for Child-Pugh A cirrhotic patients with HCC.Clavien-Dindo classification III and IV complications were more common in the SPH group compared to those in the non-SPH group (11.8% vs.5.6%).The overall complication rate was also slightly higher in the SPH group than that in the non-SPH group (47.4% vs.41.6%).Thus, we considered a relatively high risk of surgery in patients with SPH, which was consistent with the results reported by Molina et al.and Casellas-Robert et al.[ 7 , 8 ].The univariate analysis of this study suggested that SPH had no significant effect on overall complications.This also supports the conclusion that LLR is feasible for selected HCC patients with SPH.

A study by Ishizawa et al.[4]reported that the 5-year cumulative survival rate of HCC patients with Child-Pugh A SPH reached 56%, but the 5-year cumulative survival rate of HCC patients with Child-Pugh B SPH was significantly decreased to 19%.Similar studies have been published recently [ 5 , 24 ].The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates of this study were slightly lower than those reported by developed countries [ 4 , 5 , 24 ].The reason might be that the surgical indications for HCC patients with SPH are relatively wide in China.

The results of our study also suggest that the long-term prognosis of patients with SPH after LLR was not different from that of patients without SPH.A recent study performed by Zheng et al.[25]divided 156 patients into SPH and non-SPH groups and suggested that there was no difference in surgical complications and 90-day mortality between the two groups.Mid- and long-term follow-up data in their study also suggested that there was no difference in 3-year OS between the two groups, which is consistent with Lopez-Lopez et al.[5].They concluded that SPH had no significant effect on surgical and survival outcomes.Their results are in line with our study.

Not surprisingly, AFP concentration was strongly and independently associated with both OS and RFS, as shown in other studies [ 26 , 27 ].Different studies have proposed different AFP predictions, especially for liver transplantation [ 28-30 ].Our research indicated that an increase in AFP was associated with more severe disease and worse prognosis.Li and colleagues have reported that AFP concentration in 40% of patients with early-stage HCC was normal, which had limitations in predicting the prognosis of HCC [31].However, the early rise of AFP is limited to the early diagnosis of HCC [32], and our research is mainly aimed at recurrence and survival after LLR.

SPH is one of the main causes for the formation of ascites.Ascites indicates that the patient’s liver function is relatively poor,and it may also be a cause of tumor abdominal metastasis.However, no other high-quality studies have been conducted to show if ascites independently predicts worse OS and RFS, and this needs to be further explored.

A recent study reported a 2-fold increased risk of recurrence in transplantable patients beyond the Milan criteria with>2 cm HCC [33].Another study recently reported an HR of 4.27 for OS for ASA score>2 compared to ASA score ≤2 [34].In our study,tumor size and ASA score were strongly and independently associated with OS and RFS.

This study has some limitations.This research was a two-center retrospective study.The evidence strength of the results was limited.It should also be noted that the sample size of this study was small, which may lead to some biases in the results.

In conclusion, LLR for HCC complicated with SPH appears feasible in selected patients at the price of increasing operative time and blood loss.AFP, ascites, ASA, and tumor diameter may potentially predict the prognosis of HCC complicated with SPH after LLR.Prospective trials with a larger sample size are necessary to confirm these results.

Acknowledgments

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zhang-You Guo:Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft.Yuan Hong:Data curation, Methodology, Visualization.Bing Tu:Supervision, Writing - review & editing.Yao Cheng:Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing - review& editing.Xiao-Mei Wang:Conceptualization, Funding acquisition,Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China ( 81701950 and 82172135 ), Medical Research Projects of Chongqing for staff against the epidemic(2020FYYX248), and the Kuanren Talents Program of the Second Affiliated Hospital, Chongqing Medical University (KY2019Y002).

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital, Chongqing Medical University (2019-60).Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi: 10.1016/j.hbpd.2022.03.012.

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2023年4期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2023年4期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Hypermethylation of thymosin β4 predicts a poor prognosis for patients with acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure

- Novel re-intervention device for occluded multiple uncovered self-expandable metal stent (with video)

- The impact of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease on the prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after radical resection

- Clinical analysis of Wernicke encephalopathy after liver transplantation

- Hepatobiliary&Pancreatic Diseases International

- Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and its modulators in nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases