丁型肝炎抗病毒治疗药物的研究进展

王彦 张福杰

摘要:丁型肝炎病毒(HDV)是一种乙型肝炎病毒(HBV)的卫星病毒,需借助HBV包膜蛋白完成自身的组装和复制,进而建立新的感染。慢性HDV感染是病毒性肝炎最严重的形式,可加速疾病进展,提高肝癌的发生风险,HDV感染者迫切需要有效的抗病毒治疗以缓解疾病进展,但能够用于抗HDV感染的治疗药物仅包括2020年7月欧洲药品管理局有条件批准的Bulevirtide以及之前推荐使用的干扰素。目前,针对病毒复制周期的几种靶向抗病毒药物正在研究中,且前期临床试验结果表现良好。这意味着HDV的抗病毒药物研发取得了重要突破,为丁型肝炎的治疗带来了希望。本文就目前丁型肝炎抗病毒药物进行简要综述,并对相关的治疗方案进行了讨论,为丁型肝炎的治疗提供参考。

关键词:δ肝炎病毒; 病毒复制; 抗病毒药; 药物疗法

基金项目:美国庄马尔田基金会(2017-G14)

Research advances in antiviral drugs for the treatment of hepatitis D

WANG Yan, ZHANG Fujie. (Department of Infectious Diseases, Beijing Ditan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100102, China)

Corresponding author:

ZHANG Fujie, treatment@chinaaids.cn (ORCID:0000-0001-6386-9879)

Abstract:

Hepatitis D virus (HDV) is a satellite virus of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and needs the help of HBV envelope protein to complete its own assembly and replication and then establish a new infection cycle. Chronic HDV infection is considered the most severe form of viral hepatitis, which can accelerate disease progression and increase the risk of liver cancer. Effective antiviral therapy is urgently needed to delay disease progression in patients with HDV infection, but Bulevirtide conditionally approved by European Medicines Agency in July 2020 and interferon previously recommended are the only drugs used for the treatment of HDV infection. At present, studies are being conducted for several antiviral drugs targeting viral replication cycle, and early clinical trials have obtained good results. This means that important breakthroughs have been made in the development of antiviral drugs, bringing hope for the treatment of hepatitis D. This article summarizes the current antiviral drugs for hepatitis D and discusses related treatment regimens, so as to provide a reference for the treatment of hepatitis D.

Key words:Hepatitis Delta Virus; Virus Replication; Antiviral Agents; Drug Therapy

Research funding:

John C. Martin Foundation (2017-G14)

20世纪70年代,Rizzetto 等在乙型肝炎病毒(HBV)感染者中发现了一种新的RNA病毒,命名为delta,后证实为丁型肝炎病毒(HDV)[1-2]。HDV是一种有缺陷的卫星病毒,需借助HBV包膜蛋白完成病毒的组装和复制,进而建立新的感染[3]。目前认为HDV的感染主要有两种模式,即共同感染和重叠感染。不同感染模式的患者预后存在一定差异[4]。尽管HDV的致病机制尚不明确,但经大量临床队列研究证实,HDV感染能够引起非常严重的肝损伤,加速肝脏疾病进展,增加肝硬化、肝脏失代偿、肝癌甚至死亡的发生风险[5-6]。目前认为有效的抗病毒治疗能够对病毒复制产生一定抑制作用,对于改善临床预后具有重要意义[7]。本文将对HDV的复制周期以及抗病毒治疗药物的研发进展作简要综述。

1 HDV的感染模式

HDV的感染主要包括兩种模式[8-9],一种是HDV和HBV同时感染宿主,称为共同感染;另一种是在乙型肝炎表面抗原(HBsAg)携带者或慢性HBV感染者中发生HDV感染,称为重叠感染[4,8]。两种感染模式的急性期和临床表现具有显著差异。HDV和HBV共同感染时,会激发宿主较强的免疫应答,感染者很少会进展为慢性HDV感染(低于5%)[9],但急性共同感染较单独HBV感染会导致更加严重的肝损伤,甚至会导致急性肝衰竭。而HDV的重叠感染很少出现自限性恢复,超过80%的重叠感染会进展为慢性HDV感染[10-11]。在重叠感染中,病毒学模式相对一致[8,12]。HDV病毒血症出现较早,anti-HDV IgM和IgG反应活跃。在重叠感染进展为慢性感染过程中抗体滴度迅速升高,随着病毒血症的持续存在,二者维持在较高的滴度水平,而且在肝脏细胞内能够检测到HDV抗原(HDAg)[8,12]。此外,在小鼠模型中发现HDV可以在无HBV的情况下感染细胞并复制基因组[13],随后发生HBV感染时,HDV完成病毒颗粒的组装和释放。在部分队列中也发现患者未发生HBV感染[14],但可以检测到HDAg,表明HDV存在单独感染模式。尽管HDV感染会对HBV复制产生一定抑制作用,使HBV DNA滴度降低,但HDV感染可能改变肝细胞,诱导干扰素应答基因,从而导致宿主的疾病,使感染者依然表现出更为严重的肝损伤[6,15]。由此可见,HDV可能具有独特的肝脏侵害机制,靶向HDV感染开展抗病毒治疗具有重要临床意义。

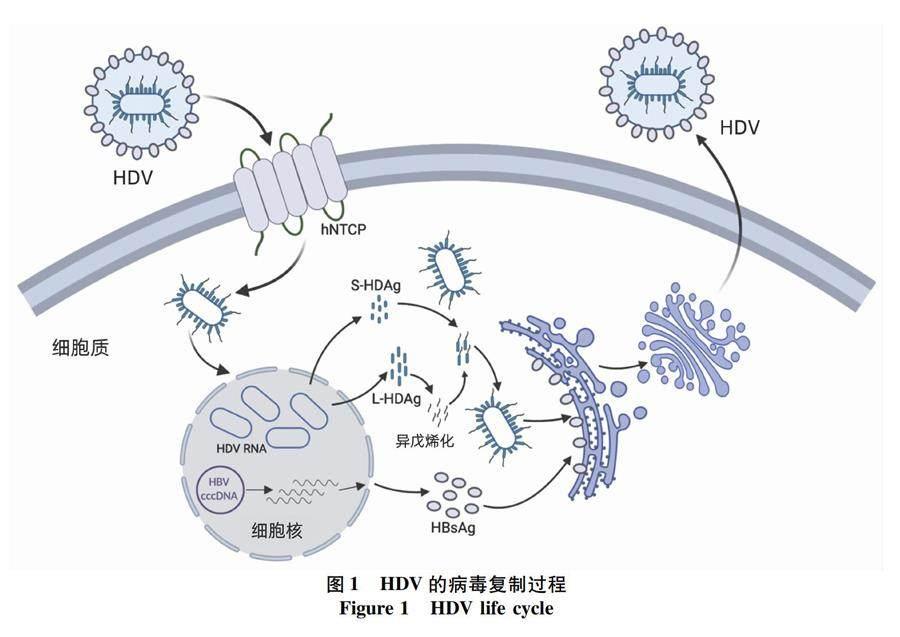

2 HDV的病毒复制

HDV为单股环形负链RNA病毒,外壳为嗜肝病毒的包膜蛋白,内核为HDV RNA和HDAg。HDAg有两种特异性的形式,分别为27 kD的L-HDAg和24 kD的S-HDAg,在HDV RNA的复制和病毒颗粒组装中发挥重要的调节作用[3]。 HDV感染细胞的主要过程如图1所示,病毒颗粒首先附着在硫酸肝素蛋白多糖[3,16],然后与牛磺胆酸钠共转运多肽(NTCP)结合,经过膜融合过程,将HDV的核糖核蛋白释放到胞浆中,然后转运入细胞核,以滚环复制的机制进行RNA的复制,合成新的基因组RNA[17-18]。 HDV基因组及反义基因组含有多个开放阅读框,能够用于蛋白的合成[4]。病毒复制过程中,L-HDAg和S-HDAg也能够转运至细胞核调节病毒的复制,或者连接到病毒基因组,形成核糖核蛋白转运到胞浆中[3]。部分L-HDAg被异戊烯化(法尼基化)修饰,通过与HBsAg相互作用形成核糖核蛋白包膜而后由内质网-高尔基体途径分泌至胞外,完成病毒的感染复制[16]。目前,针对HDV复制过程中的关键步骤,如病毒的进入、L-HDAg的修饰等[16],已开发多种靶向药物并开展临床试验,为抗HDV感染的治疗带来了希望。

3 HDV抗病毒治疗药物

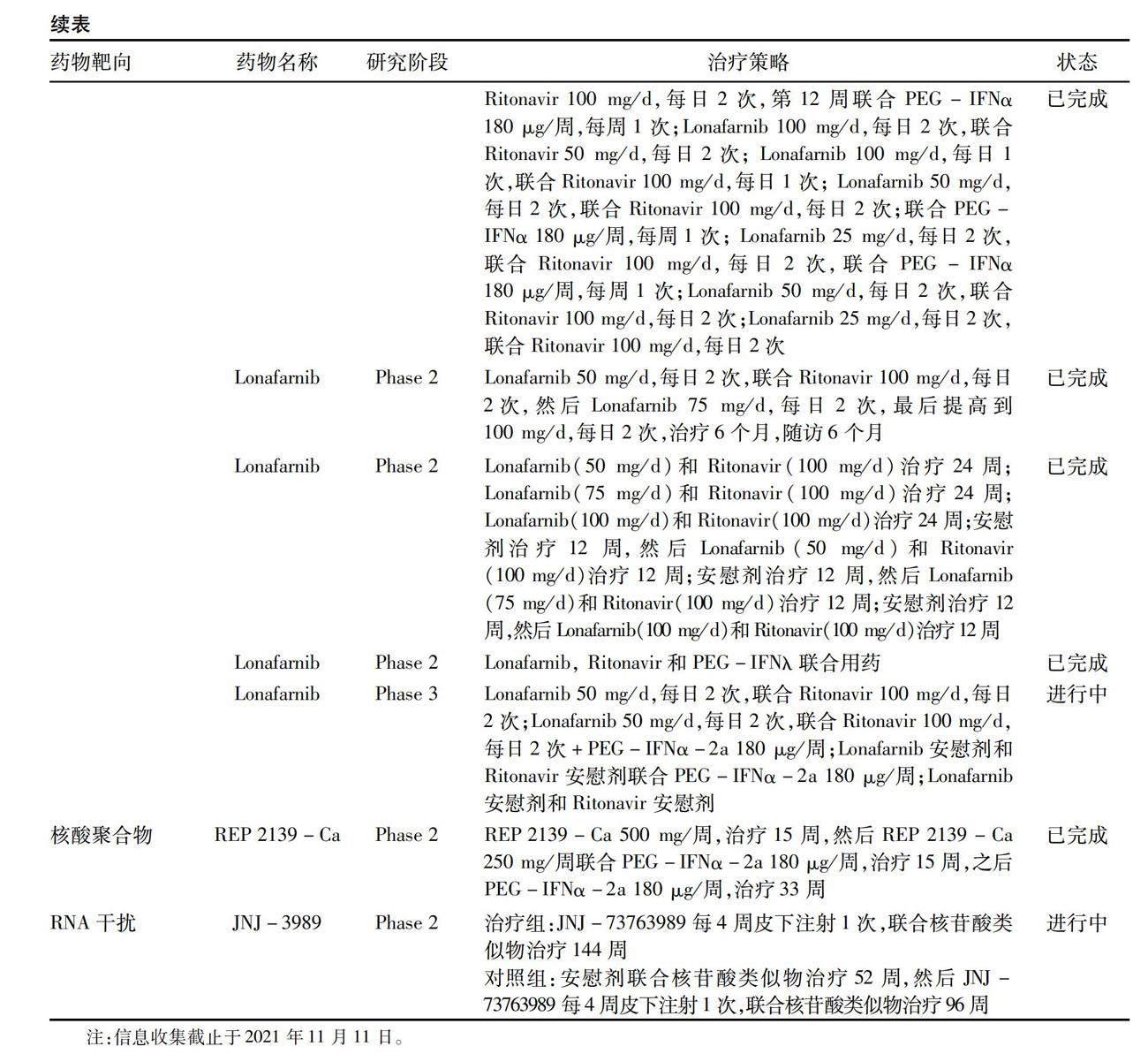

HDV感染会引起最为严重的肝损伤,急需有效的抗病毒药物和治疗方案遏制疾病进展。前期干扰素被广泛推荐用于抗HBV和HDV感染的治疗[19],但存在药物副作用和治疗后病毒反弹等问题[20]。近几年HDV靶向药物的研发成果显著,开展了多项抗HDV感染的药物临床试验(表1),2020年7月欧洲药品管理局有条件批准了进入抑制剂Bulevirtide用于丁型肝炎的治疗[21]。此外,针对HDV复制过程的其他靶向药物和增强免疫系统的联合治疗方案也正在开展药物临床试验。

3.1 干扰素治疗 干扰素具有广谱的抗病毒活性,可以分为Ⅰ型、Ⅱ型和Ⅲ型三类。其中Ⅰ型和Ⅲ型干扰素用于开发慢性丁型肝炎的抗病毒治疗。目前常用的IFNα或PEG-IFNα属于Ⅰ型干扰素,国内外已开展多项临床试验。在两项较大的前瞻性临床试验[22-23]中,仅有20%~30%的患者会出现持续性病毒学应答,且耐受性差,伴随出现严重不良反应,联合核苷类似物治疗时,亦没有显著提高患者的病毒学反应。当抗病毒治疗结束后,高达

50%的HDV RNA阴性患者出现感染复发的情况[24]。尽管如此,从近期一项长期随访的临床试验[7]中能够发现,PEG-IFNα治疗显著抑制或降低HDV RNA的水平,与改善临床长期预后相关。因此选择IFNα或PEG-IFNα进行抗HDV感染治疗,需要在可能发生的不良事件(流感症状、贫血和血小板减少等)与临床治疗效果之间进行权衡[2,6]。目前新型长效型干扰素Ropeginterferon alfa-2b治疗慢性丁型肝炎的临床试验正在开展(表1)。

PEG-IFNλ属于Ⅲ型干扰素,其与Ⅲ型IFN受体结合,导致Jak-STAT信号通路的激活[25]。由于Ⅲ型干扰素受体主要在肝细胞中表达,造血细胞和中枢神经系统细胞中表达较少,因此,与IFNα治疗相比,产生的副作用较少,具有良好的开发前景[26]。在LIMT HDV研究[27]中显示,慢性HDV感染者接受PEG-IFNλ单药治疗48周后,50%的患者能够达到HDV RNA下降2 log10以上或HDV RNA阴性,治疗结束随访24周后,有36%的患者仍具有持续的病毒学应答,除高胆红素血症、肝酶指标升高和流感样症状外,其他不良事件较少。当PEG-IFNλ联合Lonafarnib和Ritonavir开展治疗时[28],24周后96%的患者HDV RNA水平下降2 log10以上,50%的患者HDV RNA水平低于檢测下限或无法检测到,且安全性良好。目前PEG-IFNλ的三期临床试验正在开展(表1)。

3.2 进入抑制剂治疗 NTCP是HBV和HDV进入肝细胞并建立感染的关键受体,靶向NTCP对于破坏病毒建立感染具有非常重要的作用[3]。目前经美国食品药品监督管理局批准的NTCP代谢功能抑制类药物包括Irbesartan、Ezetimibe、Ritonavir和环孢素A等[29-30]。这些药物经体外细胞模型证实能够有效阻断HDV的感染或抑制HBsAg与NTCP的结合,但在临床队列中抗病毒治疗效果有待证实[29-30]。一项2期临床试验[31]显示,Ezetimibe(10 mg/d)作为单一疗法,治疗12周后并不能有效抑制患者的病毒载量,可能需要联合其他靶向药物或宿主免疫刺激药物才能实现有效的抗病毒治疗。

近期开发的靶向进入抑制剂主要包括Bulevirtide及其前体药物Myrcludex B[16],该类药物是一种阻断HBsAg preS1结构域与NTCP结合的小肽,进而阻止HDV建立感染,保护尚未感染的细胞,从而实现抗病毒功能。经Ⅰb/Ⅱa期研究[32]初步显示,治疗24周时,Myrcludex B或 PEG-IFNα-2a或其联合治疗的队列人群 HDV RNA显著下降。与单药治疗相比,联合治疗组的病毒学反应更好,治疗过程中也未发生严重不良事件,表明Myrcludex B耐受性良好,同时证实Myrcludex B和PEG-IFNα-2a对HDV有较强的协同作用。Ⅱ期临床试验显示Bulevirtide耐受性良好,不良事件主要为轻度和短暂性中性粒细胞减少、血小板减少及嗜酸性粒细胞增多等[33]。但Bulevirtide的抗病毒效果呈现出剂量依赖,Bulevirtide与PEG-IFNα联合用药具有显著的协同抗病毒作用[34-35]。2020年7月Bulevirtide已获得欧盟批准作为单一疗法或与核苷(酸)类似物联合用药,用于慢性HDV感染者抗病毒治疗,但推荐治疗使用时间尚未确定[21]。目前Bulevirtide正在全球多地慢性HDV感染者中开展抗病毒治疗的Ⅲ期研究(表1)。

3.3 异戊烯化(法尼基化)抑制剂治疗 L-HDAg的异戊烯化修饰是HDV病毒颗粒组装成熟的关键步骤,抑制该修饰将破坏病毒的组装,进而降低功能性HDV病毒颗粒的释放,是潜在的有效干预靶点[3,36]。目前研发的主要靶向药物为法尼基转移酶抑制剂Lonafarnib,已经开展了阶段Ⅰ和Ⅱ期的临床研究。2A期临床试验[37]显示,治疗28天后,低剂量组(100 mg)HDV RNA水平降低0.73 log10,高剂量组(200 mg)降低1.54 log10,呈现剂量依赖性。不良事件主要包括胃肠道副作用,如腹泻和恶心,以及体质量下降等[37]。在LOWR HDV-1研究[38]中,更高剂量的Lonafarnib(300 mg)更能降低HDV病毒载量,同时会增加胃肠道相关的不良事件发生频率。当低剂量(100 mg)Lonafarnib联合Ritonavir或PEG-IFNα治疗时,抗病毒反应效果更好,并且副作用较小[28,38]。在优化治疗方案中,三重联合治疗方案获得了最佳的病毒学应答,在治疗结束时8/9的患者HDV RNA降低了2 log10及以上[39]。由此可见,尽管Lonafarnib单独治疗能够显著降低HDV病毒载量,但联合Ritonavir或PEG-IFNα以及三种药物联合可以减少Lonafarnib的剂量,在保持抗病毒疗效的同时减少胃肠道副作用[28,37-39]。目前Lonafarnib的三期临床试验正在开展(表1)。

3.4 核酸聚合物 核酸聚合物能够抑制HBsAg包被的病毒颗粒组装和释放,因此也是一种潜在的抗HDV和HBV感染的方法[40]。REP 2139是首个开展药物临床试验用于HDV治疗的核酸聚合物[41]。12例患者经REP 2139单药治疗15周,随后REP 2139降低剂量联合PEG-IFNα治疗15周,然后PEG-IFNα单独治疗33周,研究[41]结果显示,在治疗和随访期间HBsAg水平显著下降,REP 2139单独治疗期,63.6%的患者HBsAg降低,随访期间有90.9%患者呈现下降趋势。11例患者中有7例表现为HDV RNA阴性,实现HDV功能治愈。在这些患者中,3例表现出持续的HBV病毒学抑制,4例实现HBsAg血清学转化。持续随访3.5年后[42],仅2例病毒学反弹的患者出现ALT轻微升高,没有观察到其他安全性或耐受性问题。REP 2139表现出良好的可耐受性,与PEG-IFNα联合的治疗方案为HDV功能治愈、HBV病毒学控制/功能治愈和HBsAg血清学转化提供了选择。

3.5 RNA干扰疗法 RNA干扰疗法利用小干扰RNA分子(siRNA)靶向沉默病毒共价闭合环状DNA的RNA转录本,从而抑制病毒蛋白的产生。因此推测siRNA能够清除HBsAg,进而抑制HDV的感染。ARC-520是第一种靶向HBV转录本的RNA干扰疗法,已在HBV单感染患者中开展临床试验[43],联合核苷(酸)类似物,高剂量组(2 mg/kg)ARC-520能够显著降低患者HBsAg水平,治疗结束后仍可维持对HBV的抑制疗效。仅观察到2例可能与研究药物有关的发热,表明ARC-520耐受性良好[43]。除此之外,该公司还研发出升级后的siRNA,即JNJ-3989也能够用于HBV感染的治疗,一项Ⅱa期研究[44]显示,40例患者每月接受不同剂量的JNJ-3989联合核苷酸类似物治疗3个月,治疗期间HBsAg水平迅速下降,39例患者HBsAg较基线下降1.0 log10,56%的患者在末次给药后9个月内HBsAg持续下降,其不良事件多为注射部位反应。该研究表明 JNJ-3989短期治疗也可持续抑制HBsAg。目前JNJ-3989在HBV/HDV合并感染的患者中安全性和有效性的Ⅱ期临床试验正在进行(表1)。尽管siRNA 对于改善感染者HBsAg水平表現良好,但临床试验中仍需采用与核苷酸类似物联合的治疗方案。

3.6 中药治疗 早期研究[45-46]显示,中药单独或中药与IFNα联合用药对HBV/HDV重叠感染者具有一定收益,如小柴胡汤治疗方案和IFNα配伍活血化瘀保肝中草药治疗[46]。86例HDV抗体阳性的乙型慢性活动性肝炎患者随机分为3组,分别应用小柴胡汤、联苯双酯和小柴胡汤与联苯双酯联合治疗,经过3个月的治疗后,小柴胡汤能够使90.9%的患者ALT水平恢复正常,HBsAg均有不同程度的下降,表现出良好的治疗效果[46]。不仅如此,IFNα配伍活血化瘀保肝中草药治疗HBV/HDV重叠感染者[45],1个月后患者ALT水平全部恢复正常,疗程结束后HBeAg阴转率为65%, HBV DNA检出率也显著下降,表明IFNα配伍活血化瘀中草药的治疗方法成果显著。由于该研究方案以葡萄糖、维生素C和氨基酸等常规保肝药为对照,因此,治疗方案中IFNα可能主要起到抗病毒作用,而活血化瘀类中草药主要功能可能是改善肝脏微循环,促进肝细胞再生,调节免疫功能等[45]。由此可见,抗病毒治疗药物与免疫调节药物联合用药对HBV/HDV重叠感染者肝功能的恢复具有显著疗效。

4 小结与展望

尽管乙型肝炎疫苗的实施能够有效降低HDV的感染率[47],但由于移民迁移、HIV感染以及静脉吸毒等风险因素[48-50],使全球部分地区HDV的感染率仍处于较高水平[51-52]。预计全球HDV感染者有4 800万~7 400万[51-54]。15%的慢性丁型肝炎患者会在1~2年发展成肝硬化[55],70%~80%的患者在5~10年发展成肝硬化,30年后肝硬化发生的风险提高到77%[4,53,55]。对慢性丁型肝炎患者实施有效的抗病毒治疗迫在眉睫。

随着研究的深入,HDV病毒复制及其致病机制渐趋明朗,为靶向药物的研发提供了坚实基础。2020年进入抑制剂Lonafarnib的获批,给更多新药研发提供了动力,也为丁型肝炎患者的抗病毒治疗带来了希望。由目前开展的药物临床研究可以看出,靶向药物联合干扰素,靶向药物联合核苷酸类似物,以及三种药物联合治疗,可协同提高抗病毒活性,降低单药的毒副作用,避免可能出现的耐药问题,对临床抗病毒治疗更有意义。

利益沖突声明:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

作者贡献声明:王彦负责查阅和收集资料,撰写论文;张福杰负责拟定写作思路,指导撰写文章并最后定稿。

参考文献:

[1]

RIZZETTO M, CANESE MG, ARIC S, et al. Immunofluorescence detection of new antigen-antibody system (delta/anti-delta) associated to hepatitis B virus in liver and in serum of HBsAg carriers[J]. Gut, 1977, 18(12): 997-1003. DOI: 10.1136/gut.18.12.997.

[2]GILMAN C, HELLER T, KOH C. Chronic hepatitis delta: A state-of-the-art review and new therapies[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2019, 25(32): 4580-4597. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i32.4580.

[3]LUCIFORA J, DELPHIN M. Current knowledge on Hepatitis Delta Virus replication[J]. Antiviral Res, 2020, 179: 104812. DOI: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104812.

[4]TAYLOR JM. Infection by hepatitis delta virus[J]. Viruses, 2020, 12(6): 648. DOI: 10.3390/v12060648.

[5]ALFAIATE D, CLMENT S, GOMES D, et al. Chronic hepatitis D and hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies[J]. J Hepatol, 2020, 73(3): 533-539. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.02.030.

[6]KOH C, HELLER T, GLENN JS. Pathogenesis of and new therapies for hepatitis D[J]. Gastroenterology, 2019, 156(2): 461-476. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.09.058.

[7]WRANKE A, SERRANO BC, HEIDRICH B, et al. Antiviral treatment and liver-related complications in hepatitis delta[J]. Hepatology, 2017, 65(2): 414-425. DOI: 10.1002/hep.28876.

[8]NEGRO F. Hepatitis D virus coinfection and superinfection[J]. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2014, 4(11): a021550. DOI: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021550.

[9]CAREDDA F, ROSSI E, DARMINIO MONFORTE A, et al. Hepatitis B virus-associated coinfection and superinfection with delta agent: indistinguishable disease with different outcome[J]. J Infect Dis, 1985, 151(5): 925-928. DOI: 10.1093/infdis/151.5.925.

[10]KIESSLICH D, CRISPIM MA, SANTOS C, et al. Influence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotype on the clinical course of disease in patients coinfected with HBV and hepatitis delta virus[J]. J Infect Dis, 2009, 199(11): 1608-1611. DOI: 10.1086/598955.

[11]SMEDILE A, FARCI P, VERME G, et al. Influence of delta infection on severity of hepatitis B[J]. Lancet, 1982, 2(8305): 945-947. DOI: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90156-8.

[12]TAYLOR JM. Virology of hepatitis D virus[J]. Semin Liver Dis, 2012, 32(3): 195-200. DOI: 10.1055/s-0032-1323623.

[13]GIERSCH K, HELBIG M, VOLZ T, et al. Persistent hepatitis D virus mono-infection in humanized mice is efficiently converted by hepatitis B virus to a productive co-infection[J]. J Hepatol, 2014, 60(3): 538-544. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.010.

[14]CHEMIN I, PUJOL FH, SCHOLTS C, et al. Preliminary evidence for hepatitis delta virus exposure in patients who are apparently not infected with hepatitis B virus[J]. Hepatology, 2021, 73(2): 861-864. DOI: 10.1002/hep.31453.

[15]GIERSCH K, ALLWEISS L, VOLZ T, et al. Hepatitis Delta co-infection in humanized mice leads to pronounced induction of innate immune responses in comparison to HBV mono-infection[J]. J Hepatol, 2015, 63(2): 346-353. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.011.

[16]SANDMANN L, CORNBERG M. Experimental drugs for the treatment of hepatitis D[J]. J Exp Pharmacol, 2021, 13: 461-468. DOI: 10.2147/JEP.S235550.

[17]CASEY JL. Control of ADAR1 editing of hepatitis delta virus RNAs[J]. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol, 2012, 353: 123-143. DOI: 10.1007/82_2011_146.

[18]CHEN R, LINNSTAEDT SD, CASEY JL. RNA editing and its control in hepatitis delta virus replication[J]. Viruses, 2010, 2(1): 131-146. DOI: 10.3390/v2010131.

[19]YURDAYDIN C, KESKIN O, KALKAN , et al. Interferon treatment duration in patients with chronic delta hepatitis and its effect on the natural course of the disease[J]. J Infect Dis, 2018, 217(8): 1184-1192. DOI: 10.1093/infdis/jix656.

[20]SAGNELLI C, SAGNELLI E, RUSSO A, et al. HBV/HDV co-infection: epidemiological and clinical changes, recent knowledge and future challenges[J]. Life (Basel), 2021, 11(2): 169. DOI: 10.3390/life11020169.

[21]KANG C, SYED YY. Bulevirtide: first approval[J]. Drugs, 2020, 80(15): 1601-1605. DOI: 10.1007/s40265-020-01400-1.

[22]WEDEMEYER H, YURDAYDIN C, HARDTKE S, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for hepatitis D (HIDIT-II): a randomised, placebo controlled, phase 2 trial[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2019, 19(3): 275-286. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30663-7.

[23]WEDEMEYER H, YURDAYDN C, DALEKOS GN, et al. Peginterferon plus adefovir versus either drug alone for hepatitis delta[J]. N Engl J Med, 2011, 364(4): 322-331. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912696.

[24]HEIDRICH B, YURDAYD1N C, KABAAM G, et al. Late HDV RNA relapse after peginterferon alpha-based therapy of chronic hepatitis delta[J]. Hepatology, 2014, 60(1): 87-97. DOI: 10.1002/hep.27102.

[25]LAZEAR HM, SCHOGGINS JW, DIAMOND MS. Shared and distinct functions of type I and type III interferons[J]. Immunity, 2019, 50(4): 907-923. DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.025.

[26]CHAN H, AHN SH, CHANG TT, et al. Peginterferon lambda for the treatment of HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B: A randomized phase 2b study (LIRA-B)[J]. J Hepatol, 2016, 64(5): 1011-1019. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.12.018.

[27]ETZION O, HAMID S, LURIE Y, et al. End of study results from LIMT HDV study: 36% durable virologic response at 24 weeks post-treatment with pegylated interferon lambda monotherapy in patients with chronic hepatitis delta virus infection[J]. J Hepatol, 2019, 70(Suppl 1): e32.

[28]KOH C, HERCUN J, RAHMAN F, et al. A phase 2 study of peginterferon lambda, lonafarnib and ritonavir for 24 weeks: end-of-treatment results from the LIFT HDV study[J]. J Hepatol, 2020, 73(Suppl 1): S130.

[29]NKONGOLO S, NI Y, LEMPP FA, et al. Cyclosporin A inhibits hepatitis B and hepatitis D virus entry by cyclophilin-independent interference with the NTCP receptor[J]. J Hepatol, 2014, 60(4): 723-731. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.022.

[30]BLANCHET M, SUREAU C, LABONT P. Use of FDA approved therapeutics with hNTCP metabolic inhibitory properties to impair the HDV lifecycle[J]. Antiviral Res, 2014, 106: 111-115. DOI: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.03.017.

[31]ABBAS Z, SAAD M, ASIM M, et al. The effect of twelve weeks of treatment with ezetimibe on HDV RNA level in patients with chronic hepatitis D[J]. Turk J Gastroenterol, 2020, 31(2): 136-141. DOI: 10.5152/tjg.2020.18846.

[32]BOGOMOLOV P, ALEXANDROV A, VORONKOVA N, et al. Treatment of chronic hepatitis D with the entry inhibitor Myrcludex B: First results of a phase Ib/IIa study[J]. J Hepatol, 2016, 65(3): 490-498. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.016.

[33]WEDEMEYER H, BOGOMOLOV P, BLANK A, et al. Final results of a multicenter, open-label phase 2b clinical trial to assess safety and efficacy of Myrcludex B in combination with Tenofovir in patients with chronic HBV/HDV co-infection[J]. J Hepatol, 2018, 68(Suppl 1): S3.

[34]WEDEMEYER H, SCHNEWEIS K, BOGOMOLOV PO, et al. 48 weeks of high dose (10 mg) bulevirtide as monotherapy or with peginterferon alfa-2a in patients with chronic HBV/HDV co-infection[J]. J Hepatol, 2020, 73(Suppl 1): S52-S53.

[35]WEDEMEYER H, SCHNEWEIS K, BOGOMOLOV PO, et al. GS-13-Final results of a multicenter, open-label phase 2 clinical trial (MYR203) to assess safety and efficacy of myrcludex B in cwith PEG-interferon Alpha 2a in patients with chronic HBV/HDV co-infection[J]. J Hepatol, 2019, 70(Suppl 1): e81.

[36]GLENN JS, WATSON JA, HAVEL CM, et al. Identification of a prenylation site in delta virus large antigen[J]. Science, 1992, 256(5061): 1331-1333. DOI: 10.1126/science.1598578.

[37]KOH C, CANINI L, DAHARI H, et al. Oral prenylation inhibition with lonafarnib in chronic hepatitis D infection: a proof-of-concept randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2A trial[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2015, 15(10): 1167-1174. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00074-2.

[38]YURDAYDIN C, KESKIN O, KALKAN , et al. Optimizing lonafarnib treatment for the management of chronic delta hepatitis: The LOWR HDV-1 study[J]. Hepatology, 2018, 67(4): 1224-1236. DOI: 10.1002/hep.29658.

[39]WEDEMEYER H, PORT K, DETERDING K, et al. PS-039 - A phase 2 dose-escalation study of lonafarnib plus ritonavir in patients with chronic hepatitis D: final results from the Lonafarnib with ritonavir in HDV-4 (LOWR HDV-4) study[J]. J Hepatol, 2017, 66(Suppl 1): S24.

[40]SHEKHTMAN L, COTLER SJ, HERSHKOVICH L, et al. Modelling hepatitis D virus RNA and HBsAg dynamics during nucleic acid polymer monotherapy suggest rapid turnover of HBsAg[J]. Sci Rep, 2020, 10(1): 7837. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-64122-0.

[41]BAZINET M, PNTEA V, CEBOTARESCU V, et al. Safety and efficacy of REP 2139 and pegylated interferon alfa-2a for treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis B virus and hepatitis D virus co-infection (REP 301 and REP 301-LTF): a non-randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial[J]. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2017, 2(12): 877-889. DOI: 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30288-1.

[42]BAZINET M, PNTEA V, CEBOTARESCU V, et al. Persistent control of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis delta virus infection following REP 2139-Ca and pegylated interferon therapy in chronic hepatitis B virus/hepatitis delta virus coinfection[J]. Hepatol Commun, 2021, 5(2): 189-202. DOI: 10.1002/hep4.1633.

[43]YUEN MF, SCHIEFKE I, YOON JH, et al. RNA interference therapy with ARC-520 results in prolonged hepatitis B surface antigen response in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection[J]. Hepatology, 2020, 72(1): 19-31. DOI: 10.1002/hep.31008.

[44]GANE E, LOCARNINI S, LIM T, et al. Short-term treatment with RNA interference therapy, JNJ-3989, results in sustained hepatitis B surface antigen supression in patients with chronic hepatitis B receiving nucleos(t)ide analogue treatment[J]. J Hepatol, 2020, 73(Suppl 1): S20.

[45]JIAO WJ, ZHANG F, AI QG, et al. Study on the treatment of human interferon-α combined with traditional Chinese medicine on HBV/HDV co-infection[J]. Heilongjiang Med Pharm, 1993(4): 11-12.

焦文舉, 张甫, 艾钦光, 等. 精制人白细胞α—干扰素配伍中药治疗乙、丁型肝炎病毒重叠感染的研究[J]. 黑龙江医药, 1993(4): 11-12.

[46]CHEN NL, GU F, JIA KM, et al. Treatment on 26 cases with HBV/HDV co-infection with Xiao Chaihu decoction[J]. Chin J Intern Med, 1990, 29(3): 144-146.

陈乃玲, 顾芳, 贾克明, 等. 小柴胡汤对26例乙型、丁型肝炎重叠感染治疗的探讨[J]. 中华内科杂志, 1990, 29(3): 144-146.

[47]LIN HH, LEE SS, YU ML, et al. Changing hepatitis D virus epidemiology in a hepatitis B virus endemic area with a national vaccination program[J]. Hepatology, 2015, 61(6): 1870-1879. DOI: 10.1002/hep.27742.

[48]SORIANO V, SHERMAN KE, BARREIRO P. Hepatitis delta and HIV infection[J]. AIDS, 2017, 31(7): 875-884. DOI: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001424.

[49]SERVANT-DELMAS A, LE GAL F, GALLIAN P, et al. Increasing prevalence of HDV/HBV infection over 15 years in France[J]. J Clin Virol, 2014, 59(2): 126-128. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.11.016.

[50]CHANG SY, YANG CL, KO WS, et al. Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis D virus infection among injecting drug users with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection in Taiwan[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2011, 49(3): 1083-1089. DOI: 10.1128/JCM.01154-10.

[51]SHEN DT, HAN PC, JI DZ, et al. Epidemiology estimates of hepatitis D in individuals co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B virus, 2002-2018: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J Viral Hepat, 2021, 28(7): 1057-1067. DOI: 10.1111/jvh.13512.

[52]STOCKDALE AJ, KREUELS B, HENRION M, et al. The global prevalence of hepatitis D virus infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J Hepatol, 2020, 73(3): 523-532. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.008.

[53]WANG L, ZHUANG H. Advances in hepatitis D epidemiology[J]. Chin J Viral Dis, 2021, 11(6): 420-426. DOI: 10.16505/j.2095-0136.2021.0053.

王麟, 莊辉. 丁型肝炎流行病学进展[J]. 中国病毒病杂志, 2021, 11(6): 420-426. DOI: 10.16505/j.2095-0136.2021.0053.

[54]CHEN HY, SHEN DT, JI DZ, et al. Prevalence and burden of hepatitis D virus infection in the global population: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Gut, 2019, 68(3): 512-521. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316601.

[55]FATTOVICH G, BOSCARO S, NOVENTA F, et al. Influence of hepatitis delta virus infection on progression to cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis type B[J]. J Infect Dis, 1987, 155(5): 931-935. DOI: 10.1093/infdis/155.5.931.

收稿日期:

2022-10-08;录用日期:2022-11-08

本文编辑:葛俊