Alexander disease: the road ahead

María A.Pajares, Elena Hernández-Gerez, Milos Pekny, Dolores Pérez-Sala

AbstractAlexander disease is a rare neurodegenerative disorder caused by mutations in the glial fibrillary acidic protein, a type III intermediate filament protein expressed in astrocytes.Both early (infantile or juvenile) and adult onsets of the disease are known and, in both cases, astrocytes present characteristic aggregates, named Rosenthal fibers.Mutations are spread along the glial fibrillary acidic protein sequence disrupting the typical filament network in a dominant manner.Although the presence of aggregates suggests a proteostasis problem of the mutant forms, this behavior is also observed when the expression of wild-type glial fibrillary acidic protein is increased.Additionally,several isoforms of glial fibrillary acidic protein have been described to date, while the impact of the mutations on their expression and proportion has not been exhaustively studied.Moreover,the posttranslational modification patterns and/or the protein-protein interaction networks of the glial fibrillary acidic protein mutants may be altered, leading to functional changes that may modify the morphology, positioning, and/or the function of several organelles, in turn, impairing astrocyte normal function and subsequently affecting neurons.In particular, mitochondrial function, redox balance and susceptibility to oxidative stress may contribute to the derangement of glial fibrillary acidic protein mutant-expressing astrocytes.To study the disease and to develop putative therapeutic strategies, several experimental models have been developed, a collection that is in constant growth.The fact that most cases of Alexander disease can be related to glial fibrillary acidic protein mutations,together with the availability of new and more relevant experimental models, holds promise for the design and assay of novel therapeutic strategies.

Key Words:astrocytes; endoplasmic reticulum stress; glial fibrillary acidic protein mutants;metabolism; misassembly; misfolding; neurodegeneration; oxidative stress; posttranslational modifications; unfolded protein response

Introduction

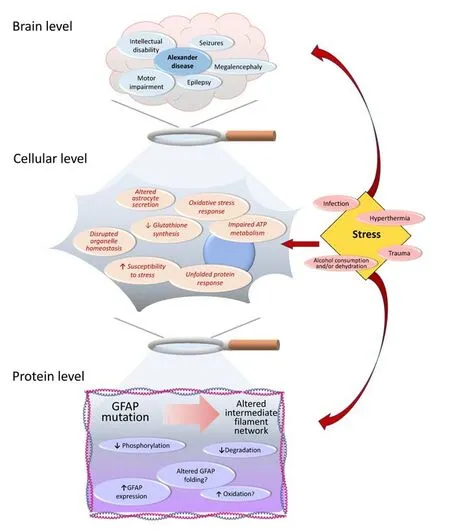

Protein aggregation, inflammation, and oxidative stress are common hallmarks of neurodegenerative diseases of diverse etiology, both common and rare.Among the latter, Alexander disease (ALXDRD in OMIM, #203450, commonly abbreviated as AxD in the scientific literature) is a fatal neurodegenerative disorder that often disrupts the white matter of the brain and hence is classified as a leukodystrophy.Its clinical manifestations may include severe motor impairment and intellectual disability, epilepsy, megalencephaly, and seizures (Messing, 2018a;Figure 1).While seizures and macrocephaly seem more common in infantile than in adult onset of AxD, palatal myoclonus has been only described in the later form of the disease (Brenner et al.,2009; Balbi et al., 2010).The cause of AxD are mostlyde novomutations in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), a type III intermediate filament protein expressed mainly in astrocytes, which are key players in brain function and homeostasis (Pekny et al., 2016; Messing, 2018a).However, some cases of inherited pathogenic mutations have been also reported (Li et al., 2006; Zang et al., 2013).The continuously increasing number of reported GFAP mutations associated with AxD can be found in a dedicated database supported and updated by Messing’s group (https://alexander-disease.waisman.wisc.edu).

AxD mutations are mainly heterozygous single-point substitutions, which can occur at diverse locations in the GFAP sequence.Remarkably, the mutant proteins display a dominant behavior disrupting the assembly of the intermediate filament network and eliciting the formation of characteristic protein aggregates, known as Rosenthal fibers, in the cytoplasm of astrocytes.Rosenthal fibers may contain not only GFAP, but also a variety of other proteins involved among others in stress response (e.g., αB-crystallin and Hsp27) (Iwaki et al., 1989; Der Perng et al., 2006), transcription (e.g., cJun)(Tang et al., 2006), and protein degradation (e.g.ubiquitin, proteasome 20S) (Lowe et al., 1988; Tang et al., 2010), together with other intermediate filament proteins and factors regulating their assembly (e.g., plectin, synemin,vimentin) (Tian et al., 2006; Pekny et al., 2014; Heaven et al., 2016).Either due to the impairment of supporting functions or toxic effects of astrocytes carrying mutant GFAP, intercellular communication with neurons, and putatively with oligodendrocytes forming the myelin around axons, and brain homeostasis are compromised in AxD leading to neurodegeneration.In this line, nitric oxide release from astrocytes has been shown to trigger neurodegeneration in an experimental model of AxD (Wang et al., 2015).Nevertheless, the molecular pathogenesis of AxD remains largely unknown.Therefore, more detailed studies on specific GFAP mutants associated with different AxD types/onsets are needed.Here we will summarize the current knowledge on several aspects of AxD emphasizing those that, in our opinion,deserve a stronger research effort in the near future.

Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein Protein Structure and Regulation

TheGFAPgene encodes the canonical GFAPα form spanning 432 residues, as well as several alternative spliced isoforms (Hol and Pekny, 2015; van Asperen et al., 2022), which differ mainly in their C-terminal end.GFAP consists of structurally disordered head and tail domains and a central coiled-coil rod domain containing the single cysteine residue (C294) of the protein.Assembly of type III intermediate filaments, as delineatedin vitro, is believed to progress through the parallel alignment of the rod domains of two monomers leading to dimers, which further associate in an antiparallel fashion to render tetramers, eight of which assemble into unit length filaments (Etienne-Manneville, 2018).Consecutive unit length filaments connect the head to tail and compact radially to form mature filaments (Etienne-Manneville, 2018).

In cells, GFAP hetero-oligomerizes with vimentin (Vim) to form the dynamic

Figure 1|Main events occurring in AxD at the brain,cellular and protein levels, with special consideration of various types of stress as factors potentially involved in the pathogenesis or progression of the disease.

network that extends from the cell membrane to the nuclear periphery,while establishing multiple interactions with various cellular structures.Loss of function studies in mice showed that GFAP and vimentin in astrocytes partially compensate for each other (Eliasson et al., 1999; Pekny et al., 1999),and thus, many revealing phenotypes of GFAP deficiency are apparent only inGfap–/–mice on aVim–/–background, i.e., in mice with astrocytes lacking both cytoplasmic intermediate filament proteins (reviewed in Ridge et al., 2022).

Both GFAP and vimentin are targets of a large variety of enzymatic and nonenzymatic posttranslational modifications that regulate their assembly and function (Etienne-Manneville, 2018).The GFAP and vimentin network establishes interactions with a multitude of proteins in various cellular structures and thus plays important roles in astrocyte migration, proliferation and organelle positioning and homeostasis.Moreover, the GFAP-vimentin organization is key for the mechanical resistance of the central nervous system to severe trauma, hypertrophy of astrocyte processes in central nervous system diseases, proper wound healing after brain and spinal cord trauma, determines neuroprotective functions of astrocytes in acute ischemic stroke, and affects post-stroke neuronal connectivity and functional recovery(reviewed in Ridge et al., 2022).

Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein Misfolding and Aggregation in Alexander Disease

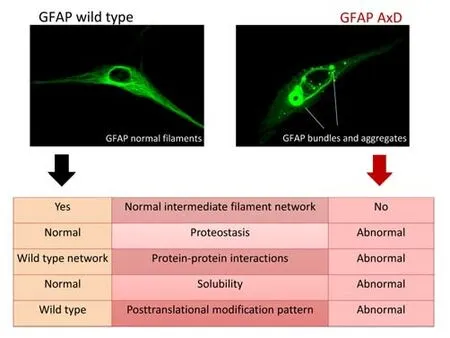

In the intricate and vastly multifaceted context of the nervous system,the variety of GFAP isoforms, their homo- or hetero-oligomerization, and different isoform ratios add additional complexity levels.Most of the work to date has been focused on the GFAPα isoform and its regulation, e.g.by phosphorylation or oxidative modifications (Inagaki et al., 1994; Viedma-Poyatos et al., 2020), while the same aspects remain either poorly analyzed or unknown for other GFAP isoforms.In this setting, the expression of AxD mutant GFAPs further confounds the picture.Importantly, the dose of mutant protein needed to perturb the wild-type (wt) GFAP network poses a relevant issue, considering that even wt GFAP displays a propensity to misfold when expressed at high levels (Messing et al., 1998).The latest data suggest diverse expression ratios between wt and distinct mutant GFAPs to attain network disruption (Heaven et al., 2019; Kang et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2022), a subject that requires further investigation.The appearance of cytoplasmic protein aggregates upon expression of AxD mutants and their accumulation as ubiquitinated forms, already suggests a proteostasis problem, likely involving misfolding, misassembly,and/or impaired degradation (Figure 2).While the similarity in sequence and secondary structure of vimentin and wt GFAP indicates an analogous assembly pathway from monomers into higher order oligomers and filaments, the monomer folding pathway has not been studied in detail for any GFAP isoform.Hence, a deeper knowledge of the GFAP folding pathway,its intermediates, and their dependence on context factors, such as the redox state, metals, pH, etc., is required to fully comprehend the impact of the mutations.The folding pathway may be altered differentially by each mutation and, if this is the case, the intermediates formed may or may not allow progression into the final“correct”monomer structure.Unproductive intermediates, those that do not reach the final“correct”monomer structure,could just accumulate and associate with a variety of proteins, giving rise to aggregates that may not be necessarily identical in composition and pathogenic significance.Another putative scenario may arise when the folding of mutant GFAPs progresses into the“correct”final monomer structure, but with local changes in charge, exposure, or orientation of side chains that may disturb the subsequent assembly process.

Figure 2|Comparison of the features of wild type and AxD mutant GFAP.

Posttranslational Modifications and Protein Interactions of Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein and Their Alterations in Alexander Disease

Detection of high molecular weight forms of GFAP AxD mutants, resistant under various denaturing conditions, suggests the occurrence of various posttranslational modifications, potentially including crosslinks (Viedma-Poyatos et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2022), although their detailed characterization is still lacking.Phosphorylation of GFAP has been identified at several positions in the protein sequence and it should be considered that AxD mutations may alter the accessibility of kinases and/or phosphatases to specific sites, in turn, changing the level and/or pattern of GFAP modification in the mutant forms.These alterations may affect another aspect of intermediate filaments,which is their dynamic nature and their subunit exchange that is regulated by phosphorylation.Fluorescence after photobleaching data have been obtained only for GFAPα and GFAPδ isoforms, the results indicating slower incorporation and dissociation of GFAPδ into the filament network (Moeton et al., 2016).However, to which point these aspects are altered by the presence of other GFAP isoforms or AxD mutants remains largely unknown.

AxD mutations may either eliminate or add target residues susceptible to posttranslational modification into GFAP, thus changing the posttranslational modification landscape and giving rise to proteoforms of unpredictable behavior.Mutants to cysteine, including R79C or R239C, causing severe forms of AxD, imply a duplication of the cysteine content in GFAP, putatively conferring the network a higher susceptibility to disruption by oxidative posttranslational modifications (Viedma-Poyatos et al., 2022).In contrast,mutants to histidine may offer other possibilities as targets for new types of phosphorylation, lipoxidation, or protein carbonyl formation.Additionally,crosstalk between diverse posttranslational modifications may be favored or precluded by the substitution of certain residues.In this line, the field lacks detailed information on the interplay between well-established posttranslational modifications identified in wt GFAP, such as phosphorylation,and non-enzymatic modifications, such as oxidation.Therefore, we are in a need of further proteomic studies to progress in the understanding of the consequences derived from AxD mutations.

GFAP establishes a large variety of protein-protein interactions that are being collected in several databases (e.g., BioGRID, https://thebiogrid.org/search.php?search=gfap&organism=all).To date, the available information refers mainly to the GFAPα isoform, although some data concerning GFAPδ interactions are also available.Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, no interactions for other GFAP isoforms have been reported.Moreover, the consequences of these protein-protein interactions are generally poorly understood.In this line, AxDassociated mutants in any GFAP isoform may alter the wild-type interaction network in ways that remain unknown.Hence, the need for interactomic studies to decipher the protein-protein interaction network for all the GFAP isoforms and their corresponding AxD mutations, to achieve a real comprehension of the normal behavior and its alterations in the disease.

Impact of Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein Mutations on Organelle Function

Expression of certain AxD mutants in cellular models also disrupts organelle homeostasis altering the positioning, morphology, and function of cellular organelles, as well as astrocytic secretion (Jones et al., 2018; Viedma-Poyatos et al., 2022).Effects of AxD mutants on organelles such as the mitochondria have been shown upon expression of some of these mutants in astrocytoma cells (Viedma-Poyatos et al., 2022).In this setting, oxidative stress was found,mainly due to the increased generation of mitochondrial ROS (Viedma-Poyatos et al., 2022).Since mitochondria are key for ATP production, the oxidative stress induced by expression of the AxD mutants may, in turn, affect the whole astrocyte metabolism (Figure 1).Thus, the imbalance between synthesis through the electron transport chain and glycolysis, whether total or partial, may not alter total ATP levels but lead to important consequences in other essential metabolic pathways, as well as in regulatory mechanisms.ATP is necessary for intermediate filament dynamics.Moreover, ATP is required to maintain the high glutathione levels found in astrocytes (8–10 mM).Glutathione is exported to the extracellular compartment where it has been proposed to serve as the source of precursors for neuronal glutathione synthesis (reviewed in McBean, 2017).Although the precise mechanisms underlying this hypothetical glutathione“exchange”have not been elucidated,it can be envisioned that any alteration in astrocytic glutathione synthesis,would have consequences in the nearby neurons.Of note, expression of a GFAP R239C AxD mutant construct in astrocytoma cells already causes a decrease in intracellular free thiol content (Viedma-Poyatos et al., 2022),mainly representing reduced glutathione (Figure 1).Whether this occurs in cells expressing other AxD mutants, as well asin vivo, potentially affecting(nearby) neurons, deserves further research.

Changes in the redox potential due to oxidative stress can alter many aspects of cell function that rely on the introduction of posttranslational modifications in key proteins of signaling cascades (Corcoran and Cotter, 2013; Truong and Carroll, 2013), which subsequently may modify the final effector molecules(e.g.proteins, DNA) in diverse subcellular locations.In fact, these changes can alter both the levels and targets of posttranslational modifications in different organelles, leading to their anomalous function, location, and/or morphology.This is achieved through the increased production of the modifying compounds (e.g., electrophiles such as 4-HNE) (Muntane et al., 2006;Martinez et al., 2008; Di Domenico et al., 2014) or by inducing the oxidation of the enzymes carrying out the modifications (e.g., kinases), in turn, leading to their inhibition or activation (Behring et al., 2020; Byrne et al., 2020; Lim et al., 2020; Shrestha et al., 2020).In this context, changes in the astrocyte redox potential induced by the expression of certain AxD mutants as described by Viedma-Poyatos et al.(2022) could impose a series of consequences derived from e.g.oxidative-regulated posttranslational modifications putatively including epigenetic changes that depend on intermediates of redox metabolism (Cyr and Domann, 2011), which need to be explored.

The protein misfolding and aggregation of AxD mutants may be related to endoplasmic reticulum stress, a condition found in most neurodegenerative diseases, and impaired unfolded protein response (Hoozemans et al., 2012;Alberdi et al., 2013; Clayton and Popko, 2016; Duran-Aniotz et al., 2017;Smith et al., 2020; Figure 1).Additionally, altered vesicle trafficking leading to deficient ATP release has been described in cells expressing some AxD GFAP mutants (Jones et al., 2018), in turn, affecting intercellular communications with neurons (by Ca2+waves).Whether there is a direct relationship between the GFAP network and these mechanisms remains to be elucidated.

Factors Contributing to Adult Onset of Alexander Disease

Although mutant GFAP alone can promote a situation of increased stress,as deduced from the analysis of patient samples, cultured astrocytes, and several models of AxD (discussed in Viedma-Poyatos et al., 2022), additional sources of stress could contribute to the onset and/or progression of the disease.Several reports have related onset of adult AxD or exacerbation of symptoms with endogenous or exogenous insults such as infections, fever,head trauma, or excessive alcohol consumption (Messing, 2018b).These stressors have in common that they can result in oxidative damage to the affected tissue.In fact, oxidative effects of long-term alcohol consumption have been reported in the adult brain (Collins and Neafsey, 2012), whereas hyperthermia induces oxidative stress in the nervous system of animal models(Chauderlier et al., 2017).In addition, there is extensive literature about how oxidative stress-derived damage occurring after traumatic brain injury affects the nervous tissue and can even hinder recovery (Rodriguez-Rodriguez et al., 2014).Therefore, oxidative stress could act as a potential inducer of the AxD pathology in individuals carrying GFAP mutations that have been asymptomatic until adulthood.In this respect, it is noteworthy that astrocytes fromGfap–/–Vim–/–mice that lack cytoplasmic intermediate filaments, as well as astrocytoma cells expressing AxD GFAP mutants, exhibit increased susceptibility to oxidative stress (de Pablo et al., 2013; Viedma-Poyatos et al., 2022; Figure 1).Being a rare disease, establishing a causal link between these factors and AxD would be challenging, and hence the experimental approaches to confirm such an association would be highly useful.

Experimental Models of Alexander Disease

Studies on AxD have used astrocytoma cell lines and primary astrocytes available from different repositories to explore the impact of a variety of GFAP mutants in cell function (Yang et al., 2022), as well as their susceptibility to modification (Viedma-Poyatos et al., 2018; Viedma-Poyatos et al., 2022).In addition, knock-in mouse (Hagemann et al., 2006), fly (Wang et al., 2015),and zebrafish models (Candiani et al., 2020), as well as neurospheres (Gomez-Pinedo et al., 2017), induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and their isogenic controls (Jones et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018; Battaglia et al., 2019; Gao et al.,2019) started to become available for research in this field.In fact, these models allowed to establish the role of AxD GFAP mutations in aspects such as altered glutamate transport (Tian et al., 2010), perturbation of organelle distribution (Jones et al., 2018), induction of autophagy (Tang et al., 2008a,b) or intercellular communication with neurons (Wang et al., 2015).However,none of these models fully recapitulated all the aspects of the disease.

To tackle the aspects that remain obscure in the GFAP field and AxD, the collection of experimental models already available is being expanded by the isolation of fibroblasts and derived iPSCs from additional patients carrying new GFAP mutations for further differentiation or reprogramming, the production of brain organoids, and animal models of AxD.These models will likely contribute to a better understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms and to the design of protective or therapeutic strategies for this disease.For detailed information on the experimental models available for the study of AxD, see the recent review by Hagemann (2022).

Therapeutic Approaches

From the clinical perspective, in lack of treatment, the therapeutic approaches employed to date are symptomatic and include antiepileptic drugs, supportive strategies, and surgical procedures, such as shunt surgery in case treatment of a hydrocephalous is needed.Nevertheless, there is no standard treatment.As the aberrant assembly is a common hallmark of mutant and excessive wt GFAP, most protective strategies explored to date have attempted to lower GFAP levels by targeting its expression.Among the compounds tested, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and curcumin used in cellular models of AxD normalized GFAP expression levels and improve folding and filament organization (Bachetti et al., 2012, 2021), while ceftriaxone decreased expression and induced elimination of mutant GFAP (Bachetti et al., 2010).Pexidartinib increased GFAP levels and decreased macrophage numbers in a mouse model of AxD (Boyd et al., 2021).Other strategies for AxD treatment were already discussed in several reviews (Messing et al., 2010; Hagemann,2022).Importantly, antisense oligonucleotides decreasing GFAP expression have shown beneficial effects in a recently developed rat model, which seems to be superior to mouse models (Hagemann et al., 2021), and has aided the design of the first clinical trial with AxD patients (https://clinicaltrials.gov/search/term=Alexander%20Disease).

Conclusions and Future Directions

In spite of the advances made to date and the availability of new experimental models for AxD study, many aspects of the disease remain obscure or unknown.The role of the different GFAP isoforms and their impact on intermediate filament structure, and function remain unknown.Furthermore,it is needed to decipher how AxD mutations impact the synthesis of the isoforms, their structure and their ability to incorporate into the network.The impact of oxidative posttranslational modifications on wt and the mutated GFAPs is only starting to be studied and, given the ever-increasing variety of cellular posttranslational modifications, elucidating their role in AxD will require considerable effort.Effects on organelle positioning and function are also being progressively uncovered, but the number of AxD mutations is large enough to require the contribution of several research groups to get a complete understanding of the subject.The development of an efficient therapy will benefit from the data that are being obtainedin vitroand from novel animal models.

Author contributions:MAP, EHG, MP and DPS wrote the manuscript.MAP,EHG and DPS carried out data search and preparation of illustrations.Allauthors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest:The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement:No additional data are available.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, andarticles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

- 中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- From static to dynamic: live observation of the support system after ischemic stroke by two photon-excited fluorescence laser-scanning microscopy

- MicroRNAs in mouse and rat models of experimental epilepsy and potential therapeutic targets

- The generation and properties of human cortical organoids as a disease model for malformations of cortical development

- Nanotechnology-based gene therapy as a credible tool in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Detection of Alzheimer’s disease onset using MRI and PET neuroimaging: longitudinal data analysis and machine learning

- A pancreatic player in dementia: pathological role for islet amyloid polypeptide accumulation in the brain