Proteomic analysis provides insights into the function of Polian vesicles in the sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus post-evisceration*

Jinlin JI , Zhenhui WANG , Wei ZHU , Qiang LI , Yinan WANG ,**

1 College of Marine and Biology Engineering, Yancheng Institute of Technology, Yancheng 224051, China

2 Dalian Ocean University, Dalian 116023, China

Abstract The Polian vesicle is the main accessory structure in the water vascular system of sea cucumbers. It can function to hold water vascular f luid under slight pressure and act as a hematopoiesis,excretory, and inf lammatory response organ. Being the only organ to remain after evisceration, the Polian vesicle may function in the survival and regeneration of sea cucumber. We performed Tandem Mass Tag(TMT)-based proteomics to identify how proteins in the Polian vesicle of Apostichopus japonicus respond to evisceration. Among the 8 453 proteins identif ied from vesicle samples before evisceration (PV0h) and at 6-h post-evisceration (PV6h) and 3-d post-evisceration (PV3d), we detected 222 diff erentially abundant proteins (DAPs). Most of the annotated DAPs were associated with cell growth and proliferation, immune response and wound healing, substance transport and metabolism, cytoskeleton/cilia/f lagella, extracellular matrix, energy production and conversion, protein synthesis and modif ication, and signal recognition and transduction. Compared with PV0h, fewer DAPs were identif ied at PV6h, and more DAPs were found at PV3d, and these DAPs were widely distributed among multiple biological processes. Our results indicate that a wide range of biological processes was induced in Polian vesicles in response to evisceration. In particular, Polian vesicles may play important roles in the restoration of coelomocytes, immune defense, and wound healing in sea cucumber. We propose that the Polian vesicle may be involved in visceral regeneration through nutrition and energy supply and by promoting dediff erentiation and migration. Together, these results provided new insights into the function of the Polian vesicle in A. japonicus post-evisceration.

Keyword: sea cucumber; Polian vesicle; evisceration; proteomics; diff erentially abundant protein

1 INTRODUCTION

The sea cucumberApostichopus japonicus(phylum Echinodermata; class Holothuroidea; family Stichopodidae) is an important marine resource.Fisheries of this species support the livelihoods of coastal dwellers along the northwest coast of the Pacif ic Ocean from 35°N to 44°N, including in Russia,China, Japan, and Korea. Sea cucumber evisceration,which occurs when animals are exposed to intense stimuli or adverse environmental conditions, is well known (Wang et al., 2015). A consequence of this evisceration is that sea cucumbers undergo major tissue loss, metabolic rate depression, and immune system modif ication (Zang et al., 2012). Visceral regeneration following natural or induced evisceration is spatially and temporally separated from other developmental events. Evisceration provides an excellent model to study organogenesis and tissue regeneration, and therefore it has been extensively studied in, for example, research on regeneration of the intestine (Sun et al., 2013, 2017b), coelomocytes(Li et al., 2018a; Shi et al., 2020), and respiratory trees (Dolmatov and Ginanova, 2009).

Like other echinoderms, sea cucumbers possess a water vascular system that provides hydraulic pressure to the tentacles and tube feet, allowing them to move and collect food items (Liao, 1997). As the main accessory structures of the water vascular system in sea cucumber, Polian vesicles are bag-like accessory structures that consist of mesothelium, muscular coat,connective tissue, and ciliated epithelium, and a lumen that is f illed with coelomic f luid (Baccetti and Rosati,1968). Polian vesicles occur in diff erent numbers in sea cucumbers, and they can hold water vascular f luid under slight pressure, until required. In addition to their function in the water vascular system, Polian vesicles are considered to play important roles in the inf lammatory response under antigenic provocation,such as erythrocyte injection, and a phylogenetic relationship between sea cucumber Polian vesicles and the vertebrate lymphoreticular system has been proposed (Smith, 1978; D’Ancona et al., 1989). More recently, Polian vesicles were proved to be one of the hematopoietic tissues and to play a key role in the generation of coelomocytes in sea cucumber (Li et al., 2019). Despite these important functions, studies into the role of Polian vesicles in sea cucumber postevisceration are lacking, which is an issue considering that the Polian vesicle is the only organ to remain within the coelom.

Proteomic analysis involves the systematic identif ication and quantif ication of the complete complement of proteins of a biological system. The quantitative measurements enable comparisons to be made between diff erent samples to detect diff erentially abundant proteins (DAPs) associated with, for example, cellular responses to a range of events. Isobaric stable isotope labeling is being increasingly applied in proteomic analysis.Comparative proteomics has been widely used in studies onA.japonicusto investigate pathogenhost interactions and identify the proteins involved(Zhang et al., 2014; Lv et al., 2019), to reveal sex diff erences in humoral immunity and physiological characteristics associated with reproduction (Jiang et al., 2020), to detect regulatory mechanisms associated with intestine regeneration (Sun et al., 2017b), and to identify key proteins involved in stress resistance (Xu et al., 2016; Huo et al., 2019).

Previously, we analyzed the transcriptomes ofA.japonicusPolian vesicles pre-evisceration and at 6-h post-evisceration to detect related gene expression patterns. Of 2 752 identif ied diff erentially expressed genes (DEGs), 1 453 were up-regulated, and 1 299 were down-regulated. The gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)enrichment analysis identif ied various DEGs and pathways involved in cell biosynthesis and immunity(Shi et al., 2020). Here, we perform a Tandem Mass Tag (TMT)-based proteomics analysis of Polian vesicles by comparing protein abundances in samples obtained pre-evisceration, and at 6-h and 3-d postevisceration, and combine this with published sea cucumber genomic data. The results greatly expands the knowledge of the functions of Polian vesicles inA.japonicusandprovides new insights into the mechanisms of evisceration and regeneration.

2 MATERIAL AND METHOD

2.1 Sample preparation

Healthy sea cucumbers (A.japonicus) weighing 60.1±10.2 g were purchased from an aquatic farm in Rizhao, Shandong Province, China, and acclimated to the laboratory environment in an aquarium with aerated seawater at 18±1 °C for 10 d. After acclimation, sea cucumbers were randomly selected and divided into three replicates (10 cucumbers in each) in each of three groups: pre-evisceration(PV0h), 6-h post-evisceration (PV6h), and 3-d postevisceration (PV3d). Evisceration in groups PV6h and PV3d was induced by intracoelomic injection of 1.2 mL of 0.35-mol/L KCl. In all three groups the ventral surface ofA.japonicuswas opened longitudinally with an aseptic scalpel, and the Polian vesicle was excised (Fig.1a). The vesicle wall was washed three times with 1×phosphate buff ered saline(PBS). The Polian vesicles from the 10 sea cucumbers in each replicate for each group were combined into a single sample. In total, nine samples (3 replicates ×3 groups) were prepared and placed in liquid nitrogen before TMT sequencing.

2.2 Protein extraction and digestion

Each sample was milled in liquid nitrogen, then lysed with lysis buff er (50-mmol/L Tris-HCL, pH 8.0,8-mol/L urea, 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS))and ultrasonicated for 5 min on ice. The supernatant of the lysate was collected after centrifugation(12 000×g, 15 min, 4 °C) and the total protein content was measured using a Bradford Protein Assay Kit(Sangon, China). Sample extracts were reduced with 2-mmol/L dithiothreitol (DTT) (56 °C) and alkylated in suffi cient iodoacetamide (room temperature in darkness) for 1 h each. Four times the volume of precooled acetone was added to the samples and mixed by vortexing. After incubation at -20 °C for 2 h or more, the mixture was centrifuged (12 000×g,15 min, 4 °C) , and the precipitated pellet was collected and washed twice using cold acetone, then dissolved in buff er containing 0.1-mol/L tetraethylammonium bromide (TEAB) (pH 8.5) and 8-mol/L urea. The protein concentration was measured using a Bradford Protein Assay Kit. Precisely 0.1-mg protein from each sample was digested for 16 h at 37 °C with 3-μg Trypsin Gold (Promega). The peptides were desalted using a C18 cartridge solid-phase extraction (SPE)from Sep-Pak (Waters, MA, USA) and then vacuum dried.

2.3 TMT labeling of peptides and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) fractionation

The peptides were labeled with TMT 10-plex reagent using a TMT10plex™ Isobaric Label Reagent Set (Thermo Fisher) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocols. One unit of labeling reagent was used for 100-μg peptides. The peptides and labeling reagent were dissolved in 100 μ L of 0.1-mol/L TEAB and 41-μL acetonitrile, respectively, then coincubated for 1 h. The reaction was terminated using ammonium hydroxide. Diff erent peptide samples labeled by TMT were equally mixed and then desalted using a desalting spin column (Thermo Fisher, 89852).The labeled peptides were separated using a C18 column (Waters BEH C18 4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm)connected to a Rigol L3000 HPLC system operating at 1 mL/min. The temperature of the column oven was set at 50 °C. Mobile phases A (2% acetonitrile) and B (98% acetonitrile) were adjusted to pH 10.0 using ammonium hydroxide and used for gradient elution.The solvent gradient was set at: 3% B for 0 min; 3%-8% B for 6 s; 8%-18% B for 11 min 54 s; 18%-32%B for 11 min; 32%-45% B for 7 min; 45%-80% B for 3 min; 80% B for 5 min; 80%-5% B for 6 s, and 5%B for 6 min 54 s. The tryptic peptides were monitored at 214 nm and the eluent was collected every minute,then merged into 15 fractions. All of the fractions were dried under vacuum and resuspended in 0.1% formic acid for subsequent assays.

2.4 Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis

Shotgun proteomics analyses were performed using an EASY-nLC 1200 system (Thermo Fisher) coupled with an Orbitrap Q Exactive HF-X mass spectrometer(Thermo Fisher) operating in the data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode. A total of 2-μg peptides reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid was injected onto an Acclaim PepMap100 C18 Nano-Trap column(2 cm×100 μm, 5 μm). Peptides were separated on a ReproSil-Pur 120 C18-AQ analytical column (15 cm×150 μm, 1.9 μm) using a linear gradient of eluent B (0.1% formic acid in 80% acetonitrile) in eluent A (0.1% formic acid in H2O). The solvent gradient was set at: 5%-10% B for 2 min; 10%-40% B for 105 min; 40%-50% B for 5 min; 50%-90% B for 3 min; and 90%-100% B for 5 min. The separated peptides were analyzed using a Q-Exactive HF-X mass spectrometer with spray voltage 2.3 kV and capillary temperature 320 °C. Full MS scans from 350-1 500m/zwere conducted at 60 000 resolution(at 200m/z), with an automatic gain control (AGC)target value of 3×106and maximum ion injection time of 20 ms. A maximum of 40 precursor ions with the highest abundance from the full MS scan was selected for high energy collision dissociation (HCD) fragment analysis at 45 000 resolution (at 200m/z), with an AGC target value of 1×105, maximum ion injection time of 45 ms, normalized collision energy 32%,intensity threshold 8.3×105, and dynamic exclusion parameter 60 s. LC-MS/MS testing was performed by Novogene Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

2.5 Protein identif ication and quantif ication

The resulting spectra were searched individually against theA.japonicusreference genome(National Center for Biotechnology Information GCA_002754855.1) using Proteome Discoverer 2.2 (Thermo Fisher). Proteins that contained at least one unique peptide were identif ied with a false discovery rate of <0.01 for the peptide and protein.Reporter Quantif ication (TMT 10-plex) was used for TMT quantif ication. The signif icance of diff erences in the protein composition among diff erent groups was determined by the Mann-Whitney U Test.P-value <0.05 and fold change >1.20 or <0.83 were set as the thresholds for screening DAPs. The mean values of the abundances of the DAPs in each group were calculated and fuzzy C-means clustering of DAPs was analyzed using the “TCseq” package in R. The raw proteomics data was submitted to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the iProX partner repository (Ma et al., 2019).

2.6 Protein annotation and functional analysis of the DAPs

Gene ontology (GO) and InterPro (IPR) analyses of the DAPs were performed using InterProScan 5 (Jones et al., 2014). The Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG; http://www.geneontology.org/) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)(http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) databases were used to analyze protein families and pathways. GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses of the DAPs were performed and terms or pathways withP-values<0.05 were considered signif icantly enriched. The fold change of annotated DAPs was visualized using the “heatmap” package in R. SignalP 4.1 (Petersen et al., 2011) and TMHMM (Krogh et al., 2001) were used to predict the presence of signal peptides and transmembrane domains, respectively, in the DAPs.

3 RESULT

3.1 Overview of the proteomics data

A total of 444 064 spectra were obtained by TMTLC-MS/MS proteomic analysis from the nine samples(comprising 10 pooled sea cucumber Polian vesicles in each of three replicates in three groups). After f iltering to eliminate low-scoring spectra, 49 863 peptides were obtained, with 8 453 proteins identif ied from the pre- and post-evisceration samples. Of the identif ied proteins, 8 120, 5 391, 3 555, and 7 368 proteins were assigned terms from the KEGG, GO,COG, and IPR databases, respectively (Fig.1b).Most of the proteins (96%; 8 120/8 453) were assigned to KEGG pathways, including cellular processes, environmental information processing,genetic information processing, human diseases,and metabolism and organismal systems (Fig.1c).The identif ication, annotation, and quantitative analysis details for these proteins are available in Supplementary Table S1.

3.2 DAPs identif ied post-evisceration

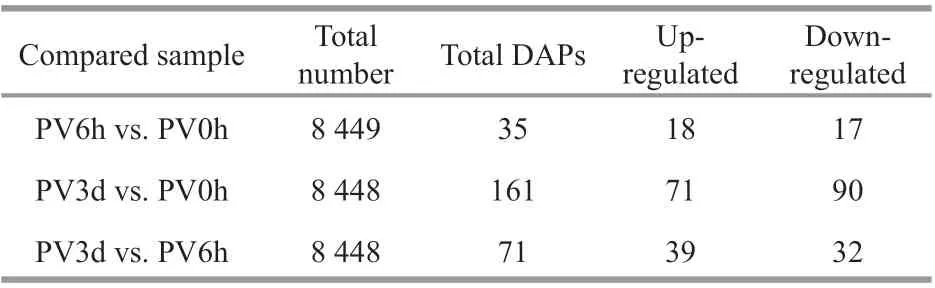

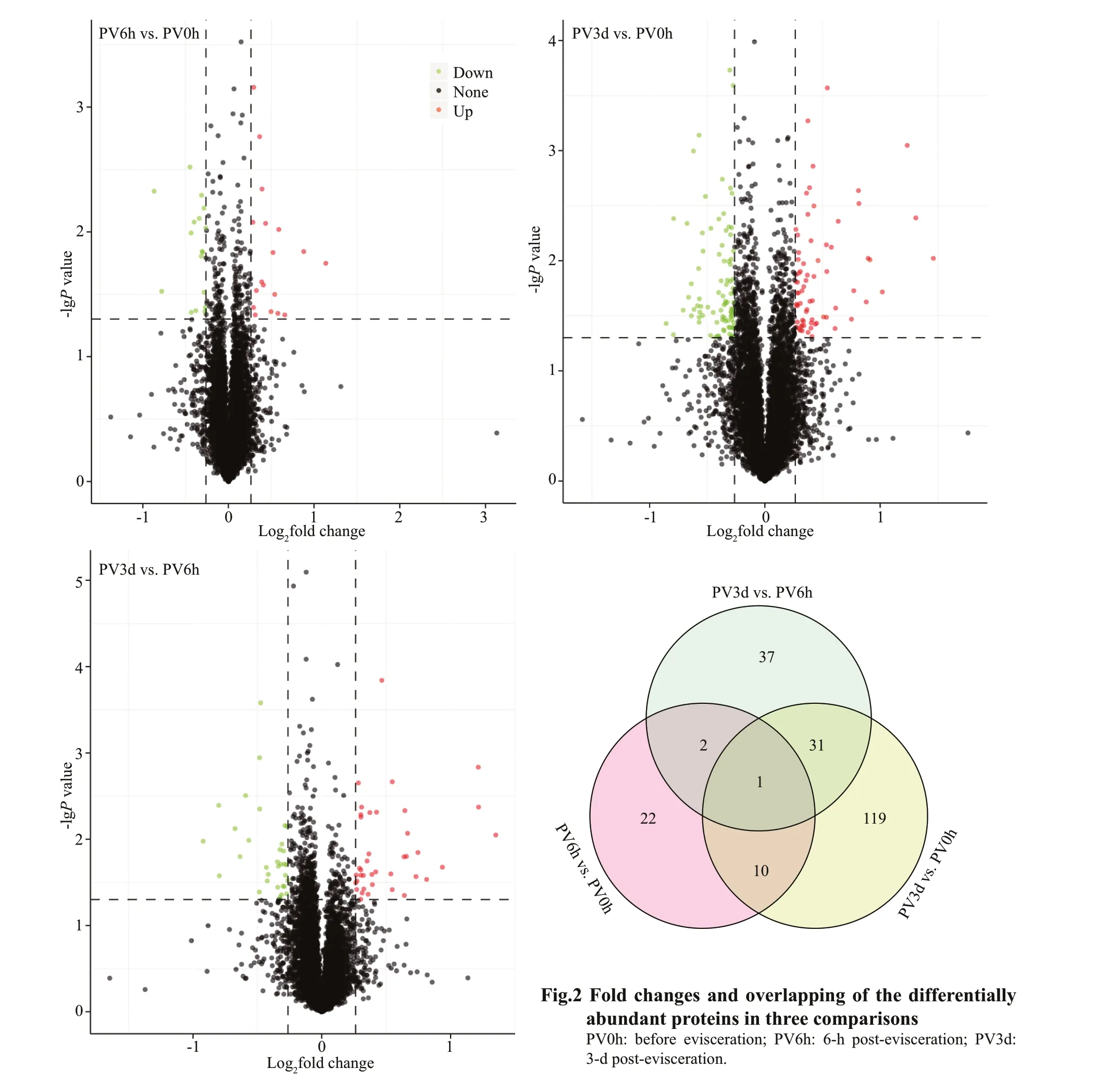

Pairwise comparisons among the diff erent groups detected 222 DAPs in the post-evisceration Polian vesicle samples, withP-values <0.05 and fold change>1.20 or <0.83 (Fig.2; Supplementary Table S2).Only 35 proteins were signif icantly diff erentially abundant in the PV6h vs. PV0h comparison,whereas 161 proteins were signif icantly diff erentially abundant in the PV3d vs. PV0h comparison. Another 71 proteins were signif icantly diff erentially abundant in the PV3d vs. PV6h comparison (Table 1). Many of the DAPs were common in at least two of the comparisons, and a number of DAPs were specif ic in the PV3d vs. PV6h comparison (Fig.2). The fuzzyC-means clustering divided the 222 DAPs into six clusters, with 69, 40, 32, 13, 54, and 14 proteins in clusters 1-6, respectively (Fig.3).

Table 1 Diff erentially abundant proteins (DAPS) in three comparisons

3.3 Functions of DAPs post-evisceration

Among the 222 DAPs, 35 were unannotated,including 15 DAPs with limited information about their domains (Supplementary Table S3).Considering the protein descriptions from genome annotations and the annotations assigned by searches against the various databases, we manually classif ied the other 187 DAPs. Most of the annotated DAPs were associated with cell growth and proliferation,immune response and wound healing, substance transport and metabolism, cytoskeleton/cilia/f lagella,extracellular matrix (ECM), energy production and conversion, protein synthesis and modif ication,and signal recognition and transduction (Fig.4;Supplementary Table S4). The DAPs from the PV3d vs. PV0h comparison were associated with all these biology processes or functions. While the DAPs from the PV6h vs. PV0h comparison were mainly associated with substance transport and metabolism,immune response and wound healing, cell growth and proliferation, and cytoskeleton/cilia/f lagella.

The SignalP 4.1 and TMHMM analyses detected 24 secretory proteins and three transmembrane proteins among the 222 DAPs (Supplementary Table S5).Among the secretory proteins, six were associated with immune response and wound healing, and f ive were associated with ECM. Seven of the secretory DAPs were unannotated proteins, and two of them had a Plasminogen-Apple-Nematode (PAN)/Apple domain. The annotated secretory and transmembrane DAPs are marked in Fig.4.

3.4 GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DAPs after evisceration

Fig.1 Proteomic analysis of Polian vesicles in Apostichopus japonicas

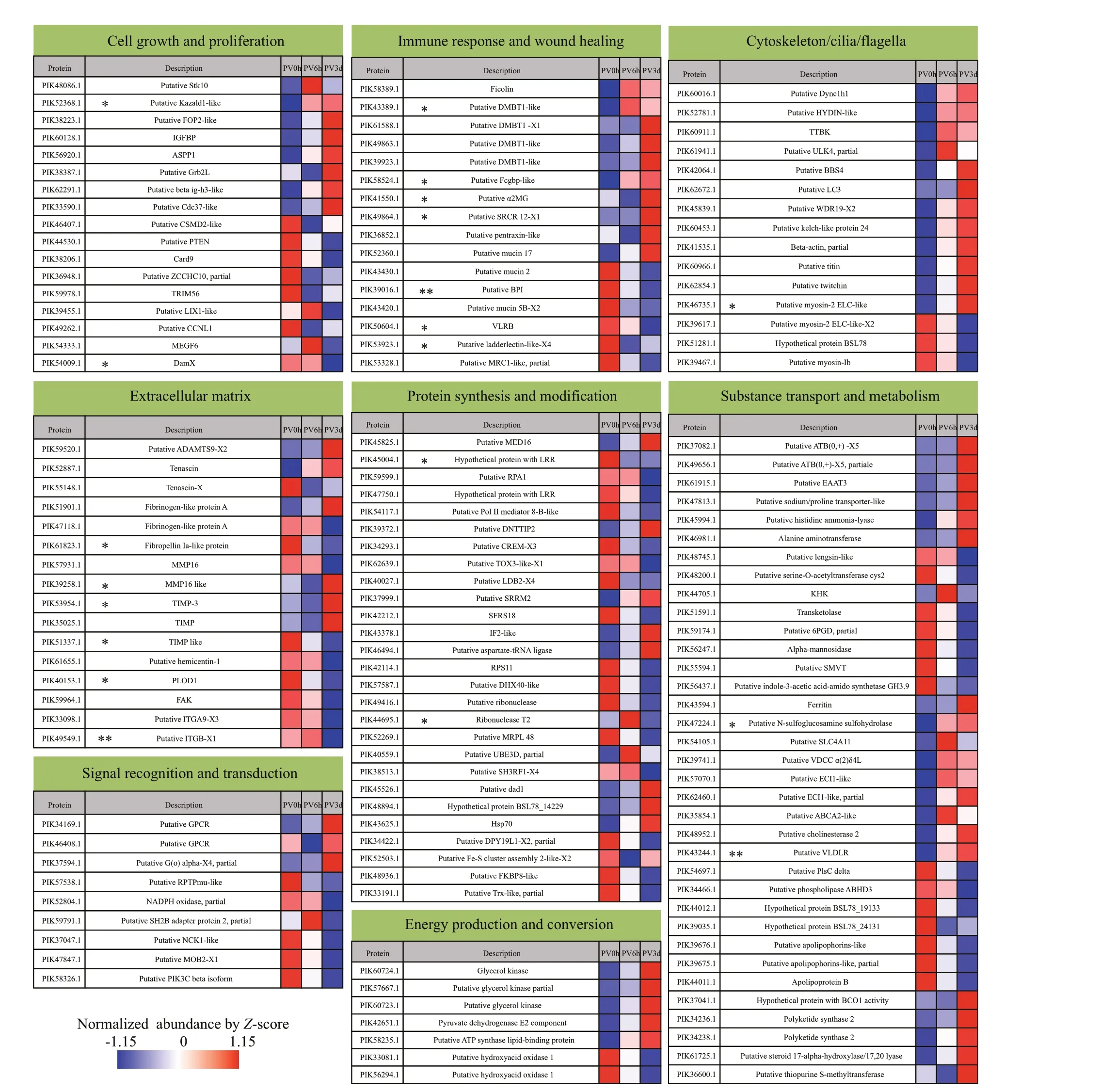

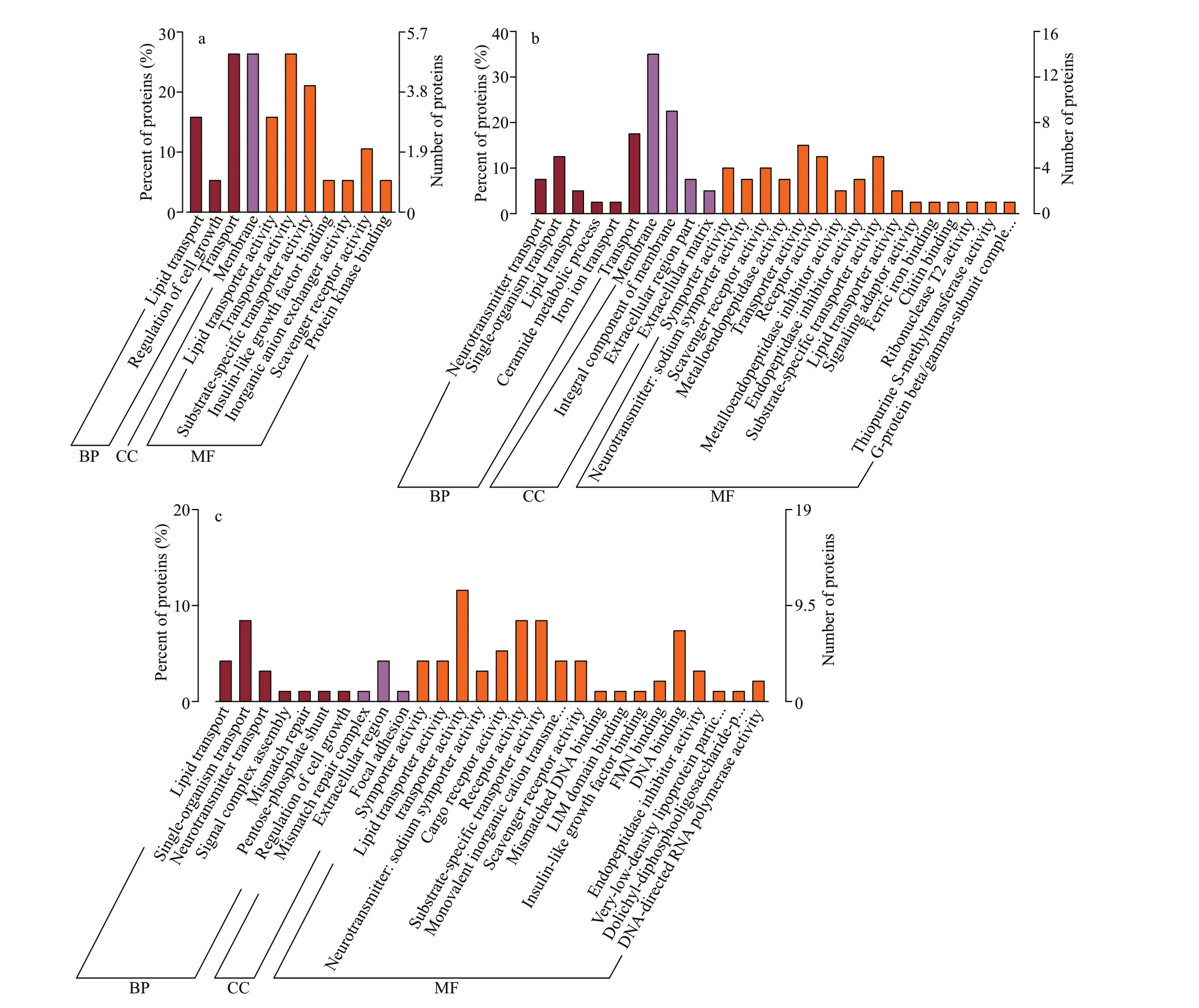

The GO functional enrichment analysis identif ied 19 DAPs in the PV6h group (compared with the PV0h group) that were assigned signif icantly enriched GO terms (P<0.05); three were under the biological process (BP) category, seven were under the molecular function (MF) category, and one was under the cellular component (CC) category (Fig.5a).Most enriched MF terms were associated with substance transport, particularly lipid transport. The MF term insulin-like growth factor binding (1 DAP)and BP term regulation of cell growth (1 DAP) were associated with cell growth. One KEGG pathway, fat digestion and absorption, was signif icantly enriched,and the down-regulated DAP annotated as ATPbinding cassette sub-family A member 2-like was among the DAPs annotated with this pathway.

In the PV3d vs. PV0h comparison, 95 DAPs were assigned 28 signif icantly enriched GO terms(P<0.05) under the BP (7), MF (18), and CC (3)categories (Fig.5c). The top f ive enriched GO terms were transporter activity (MF, 11 DAPs), receptor activity (MF, 8 DAPs), single-organism transport (BP,8 DAPs), substrate-specif ic transporter activity (MF,8 DAPs), and DNA binding (MF, 7 DAPs). Additional to lipid transport, multiple substance transport-related terms were enriched. The signif icantly enriched KEGG pathways (P<0.05) were cholinergic synapse,metabolism of materials (glycerolipid metabolism,fat digestion and absorption, vitamin digestion and absorption), signaling pathways (estrogen,peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR),erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene B (ErbB),and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain(NOD)-like receptor), and RNA polymerase.

Fig.3 Protein abundance in six fuzzy C-means derived clusters

In the PV3d vs. PV6h comparison, 38 DAPs were assigned 26 signif icantly enriched GO terms (P<0.05)under the BP (6), CC (4), and MF (16) categories(Fig.5b). The enriched GO terms included membrane(CC, 14 DAPs), integral component of membrane(CC, 9 DAPs), transport (BP, 7 DAPs), transporter activity (MF, 6 DAPs), and three terms, receptor activity (MF), single-organism transport (BP), and substrate-specif ic transporter activity (MF), had f ive DAPs each. Many DAPs were enriched in CC terms related to membrane. ECM-related terms were also enriched, as were multiple substance transport-related terms, including iron ion transport (BP, 1 DAP). The signif icantly enriched KEGG pathways (P<0.05)were ferroptosis, glutamatergic synapse, signaling pathways (PPAR, gonadotropin-releasing hormone(GnRH), estrogen, and relaxin), cell adhesion (cell adhesion molecules, focal adhesion), proteoglycans in cancer, and glycerolipid metabolism.

4 DISCUSSION

Fig.4 Evisceration-induced changes in the proteomes of Polian vesicles pre- and post-evisceration

The Polian vesicle may have an important role in the survival and regeneration of sea cucumber because it is the only organ that remains in the coelom after evisceration. While complete visceral regeneration in sea cucumber requires 2 to 3 weeks, coelomocytes can recover to pre-evisceration levels within 6-h postevisceration, and some intracavity tissues gradually regenerate from 3-d post-evisceration, indicating that notable changes occur at the early stage of regeneration (Zhang et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018a). In this study, we performed TMT-based proteomics of Polian vesicles to investigate the role of this vesicle in the early regeneration process.

Fig.5 Gene ontology (GO) annotations of the diff erentially abundant proteins (DAPs)

Compared with pre-evisceration levels, some proteins present in the Polian vesicle showed diff erential abundance at 6-h and 3-d postevisceration, indicating an active response of the Polian vesicle to the pressure of evisceration. Most of the annotated DAPs were associated with cell growth and proliferation, immune response and wound healing, substance transport and metabolism,cytoskeleton/cilia/f lagella, ECM, energy production and conversion, protein synthesis and modif ication,and signal recognition and transduction. Compared with pre-evisceration levels, more DAPs were found at 3-d post-evisceration than at 6-h post-evisceration,and these DAPs were involved in multiple biological processes. Our results indicated that a wide range of biological processes was induced in Polian vesicles in response to evisceration and that the response was gradually strengthened.

During eviscerationofA.japonicus, almost all the coelomocytes in the coelom cavity are lost along with the coelomic f luid and internal organs. However, the number of coelomocytes in the coelom cavity was found to recover rapidly at 6-h post-evisceration (Li et al., 2018a). Considering that the Polian vesicle is full of coelomic f luid as well as coelomocytes and connected to the coelom cavity through the water vascular system, we presumed that the Polian vesicle had an important role in this replenishment by pumping out the trapped coelomocytes. Furthermore,both inner and outer epithelia of the Polian vesicle have microvilli and cilia on their surfaces, which might facilitate the migration and f lowing of coelomocytes. Consistent with this speculation, we found that several cilia/f lagella-related proteins were signif icantly up-regulated at PV6h in this study,including serine/threonine-protein kinase Unc51-like kinase 4 (ULK4), which may be involved in cerebrospinal f luid circulation and ciliogenesis (Liu et al., 2016), and hydrocephalus-inducing protein-like(HYDIN), which is a ciliary protein with a unique role in ciliary motility (Smith, 2007). The migration of coelomocytes replenishes the coelomocytes in the coelom cavity as an emergency response; however,continual and enhanced hematopoiesis processes are necessary to make up for the huge loss of coelomocytes.

We previously demonstrated that the Polian vesicle, rete mirabile, and respiratory tree were fundamental tissues involved in hematopoiesis inA.japonicusunder normal conditions (Li et al., 2019).Hemocyte proliferation is known to take place in specialized hematopoietic organs that provide an environment where undiff erentiated blood stem cells are able to self-renew and, at the same time,generate off spring that diff erentiate into diff erent blood cell types (Grigorian and Hartenstein, 2013).In a previous study, a number of DEGs related to cell proliferation and diff erentiation were found in Polian vesicles at 6-h post-evisceration compared with pre-evisceration levels, and these DEGs were enriched in several signaling pathways involved in cell proliferation and diff erentiation (Shi et al.,2020). Here, we found that many DAPs related to cell growth and proliferation were consistently and remarkably regulated post-evisceration, including upregulated growth factor-related proteins, such as the insulin-like growth factor binding protein (IGFBP)(Wirthgen et al., 2016), transforming growth factor ig-h3 (beta ig-h3-like) (Oh et al., 2005), and growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (Grb2L) (Ge et al.,2017), as well as a oncogene partner called f ibroblast growth factor receptor 1 and oncogene partner 2(FOP2) (Jin et al., 2011). In contrast, several proteins reported to suppress tumors or cell proliferation were down-regulated, including cub and sushi multiple domains 2 (Zhang and Song, 2014), tripartite motifcontaining protein 56 (TRIM56) (Chen et al., 2018),phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) (Gupta and Leslie, 2016), caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 9 (Card9) (Pan et al., 2020), and zinc f inger CCHC domain-containing protein 10 (ZCCHC10)(Ohira et al., 2019). Additionally, GO terms and KEGG pathways associated with cell proliferation and diff erentiation were signif icantly enriched,such as ErbB receptor (Masunaga et al., 2017) and PPAR signaling pathway (Lee et al., 2015; Li et al.,2018b; Magadum and Engel, 2018). These results consistently suggested that an active hematopoiesis process was initiated in the Polian vesicle in response to evisceration. Notably, some DAPs, such as upregulated serine/threonine-protein kinase 10 (Stk10),also known as lymphocyte-oriented kinase (LOK),(Walter et al., 2003) and apoptosis-stimulating of p53 protein 1 (ASPP1) (Yamashita et al., 2015)were reported to be present in high abundance in hematopoietic tissue or hematopoietic stem cells,further conf irming the hematopoietic function of the Polian vesicle. Taken together, these results suggest that the Polian vesicle participates in coelomocyte restoration post-evisceration as both a storage organ and hematopoietic tissue.

The Polian vesicle was reported to be involved in inf lammatory responses to some adverse stresses(Smith, 1978; D’Ancona and Rizzuto, 1989). When almost all the coelomocytes are excreted during evisceration, sea cucumber immunity is weakened, and therefore the Polian vesicle might play an important role in increasing immunity post-evisceration. We previously demonstrated that several immune-related genes were diff erentially expressed and that immunerelated pathways were enriched in the Polian vesicle post-evisceration, indicating a role for the Polian vesicle in immunity inA.japonicus(Shi et al., 2020).Here, we reported various DAPs associated with immune response and wound healing in the Polian vesicle after evisceration, as well as the enrichment of immune-related NOD-like receptor signaling pathway(Platnich and Muruve, 2019). These results indicated a strengthened immune state in Polian vesicles responding to evisceration. In addition, most of the up-regulated DAPs predicted as secretory proteins,such as acute-phase protein α-macroglobulin (α2MG)(Varma et al., 2017), and mucosa protein Fcgbp and agglutinin DMBT1 (Houben et al., 2019), may also function in the coelom cavity, especially for wound healing after evisceration.

The functions of the Polian vesicle in coelomocytes migration, proliferation, immune response, and wound healing are based on essential supplies of substances and energy. Energy and nutrients are also extremely important for survival and regeneration of sea cumber because food intake is totally ceased due to intestine lose after evisceration. Various metabolic and physiological parameters were found to change dramatically post-evisceration, with lipids and carbohydrates being consumed as energy sources (Tan et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2017a). Here, we found that many proteins associated with substance transport and metabolism, and energy production and conversion, were signif icantly increased in the Polian vesicle, especially 3-d post-evisceration. These DAPs were predicted to be involved in transport and metabolism of multiple kinds of substances(amino acid, carbohydrate, coenzyme, inorganic ion,lipid, and secondary metabolites). Corresponding GO terms and KEGG pathways were also enriched,including those associated with lipid transport and metabolism. These results indicate an augment metabolic progression in the Polian vesicle response to evisceration, which would contribute to the urgent needs of survival and regeneration. The sea cucumber Polian vesicle was also considered to be a primitive“excretory” organ that may have adapted to facilitate the passage of waste-f illed amoebocytes through its tissues into the coelom (Baccetti and Rosati, 1968).Hence, we speculated that the Polian vesicle might facilitate excretion of dysfunctional metabolites and disintegrating coelomocytes in response to an adverse stimulus such as evisceration.

The ECM is recognized to play key regulatory roles because it orchestrates cell signaling, and various functions, properties, and morphology. Among them, proteins/glycoproteins such as collagens and tenascins, and their cell receptors such as integrins,are involved in cell adhesion. Some enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), a family of endopeptidases involved in the degradation of various proteins in ECM, and their natural inhibitors,tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs),play important roles in cell proliferation, migration,diff erentiation angiogenesis, and immunity regulation(Cui et al., 2017; Dolmatov et al., 2021; Karamanos et al., 2021). We found that ECM-related proteins were signif icantly regulated in Polian vesicle postevisceration, indicating an active ECM remodeling response to evisceration, which might be related to coelomocyte proliferation and migration, and immunity regulation in Polian vesicles. Beside these,several DAPs might be secreted and then play roles in regeneration. Dediff erentiation of specialized cells in the remnant of organ and the migration of dediff erentiated cells are fundamental for regeneration in sea cucumber (Wang et al., 2015; Dolmatov, 2021).In these processes, ECM transformation occurred to promote the migration of dediff erentiated cells and the formation of new tissues. Two MMP genes,ajMMP-2andajMMP-16, have been cloned inA.japonicus, and were thought to form a road for migrating cells and accelerate cell migration (Miao et al., 2017). Because these genes were expressed only at the initial stage of regeneration, it was suggested that they may be involved in degradation of the esophageal ECM and dediff erentiation of coelomic epithelial cells and enterocytes (Miao et al., 2017;Dolmatov et al., 2021). In the present study, several members of MMP and TIMP with varied regulation trends were found, indicating a complicated process of ECM remodeling. However, the up-regulation and down-regulation of secreted proteins MMP16-like and TIMP-like in PV3d respectively suggested that they might contribute to visceral regeneration through promoting dediff erentiation and migration.

It should be mentioned that a number of unannotated DAPs were found in the present study, especially seven that were identif ied as secretory proteins. These DAPs might be specif ic to echinoderms and may play important roles in the recovery of sea cucumber postevisceration. Further estimation of their functions using more methods is needed.

5 CONCLUSION

The Polian vesicle exhibited a wide range of biological functions in response to evisceration inA.japonicus, and the response gradually strengthened.The Polian vesicle played an indispensable role in the restoration of coelomocytes after evisceration both as a storage and hematopoietic tissue. Immune processes were elevated in the Polian vesicle, and some DAPs may be secreted into the coelom cavity and contribute to wound healing after evisceration.To support these functions, augment metabolic progression was induced in Polian vesicle and was supposed to meet the urgent needs of nutrition and energy for survival and regeneration. In addition,several ECM-related DAPs may be secreted and then play roles in regeneration, especially by promoting dediff erentiation and migration. Collectively, these results provide new insights into the functions of Polian vesicles inA.japonicuspost-evisceration.

6 DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The raw proteomic data have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the iProX partner repository, with the dataset identif ier PXD025117.

Journal of Oceanology and Limnology2022年5期

Journal of Oceanology and Limnology2022年5期

- Journal of Oceanology and Limnology的其它文章

- Comparison of three f locculants for heavy cyanobacterial bloom mitigation and subsequent environmental impact*

- Key physiological traits and chemical properties of extracellular polymeric substances determining colony formation in a cyanobacterium*

- Involvement of the ammonium assimilation mediated by glutamate dehydrogenase in response to heat stress in the scleractinian coral Pocillopora damicornis*

- UV-B irradiation and allelopathy by Sargassum thunbergii aff ects the activities of antioxidant enzymes and their isoenzymes in Corallina pilulifera*

- Cyanobacterial extracellular alkaline phosphatase: detection and ecological function*

- Full-length transcripts facilitates Portunus trituberculatus genome structure annotation*