Icariin ameliorates memory deficits through regulating brain insulin signaling and glucose transporters in 3×Tg-AD mice

Fei Yan ,Ju Liu ,Mei-Xiang Chen ,Ying Zhang ,Sheng-Jiao Wei ,Hai Jin ,Jing Nie,Xiao-Long Fu,Jing-Shan Shi,Shao-Yu Zhou,,Feng Jin,

Abstract Icariin,a major prenylated flavonoid found in Epimedium spp.,is a bioactive constituent of Herba Epimedii and has been shown to exert neuroprotective effects in experimental models of Alzheimer’s disease.In this study,we investigated the neuroprotective mechanism of icariin in an APP/PS1/Tau triple-transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease.We performed behavioral tests,pathological examination,and western blot assay,and found that memory deficits of the model mice were obviously improved,neuronal and synaptic damage in the cerebral cortex was substantially mitigated,and amyloid-β accumulation and tau hyperphosphorylation were considerably reduced after 5 months of intragastric administration of icariin at a dose of 60 mg/kg body weight per day.Furthermore,deficits of proteins in the insulin signaling pathway and their phosphorylation levels were significantly reversed,including the insulin receptor,insulin receptor substrate 1,phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase,protein kinase B,and glycogen synthase kinase 3β,and the levels of glucose transporter 1 and 3 were markedly increased.These findings suggest that icariin can improve learning and memory impairments in the mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease by regulating brain insulin signaling and glucose transporters,which lays the foundation for potential clinical application of icariin in the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

Key Words:Alzheimer’s disease;amyloid-beta;brain insulin signaling;glucose transporter;glucose uptake;icariin;memory;neurodegenerative disease;tau hyperphosphorylation;triple-transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mice

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and diabetes,especially type 2 diabetes,share many common pathological characteristics,including insulin resistance,glucose hypometabolism,energy shortage,amyloid-beta (Aβ) accumulation,and tau hyperphosphorylation,which supports the proposal that AD is a metabolic disease and,thus,has been defined as“type 3 diabetes”(Steen et al.,2005;Salas and De Strooper,2019;Nguyen et al.,2020;Ferreira et al.,2021;Kshirsagar et al.,2021).It has been reported that impaired brain insulin signaling,which causes insulin resistance and reduced brain glucose uptake,emerges in the early stages of AD and correlates with neurodegeneration and memory impairment (Simpson et al.,1994;Liu et al.,2008;Chua et al.,2012;Tramutola et al.,2020;Hendrix et al.,2021).Insulin exerts beneficial effects on the brain,such as trophic effects on neurons and synapses and promotion of glucose homeostasis (Lee et al.,2011;Dodd and Tiganis,2017).In addition,insulin-mediated signaling interacts intricately with Aβ peptide deposition and tau hyperphosphorylation,which are two classic pathological features of AD(Ho et al.,2004;Marciniak et al.,2017;Zhang et al.,2018;Gali et al.,2019;Kim et al.,2019).Therefore,impairment of brain insulin signaling may lead to both AD pathology and glucose dysregulation.Glucose is the dominant energy source of the mammalian brain,which has a high energy requirement,and is transported from blood to brain cells by glucose transporters (GLUTs).However,reduced GLUT expression and glucose hypometabolism have been observed in AD and reflect AD pathology and symptoms (Winkler et al.,2015;Daulatzai,2017;An et al.,2018).Taken together,impaired brain insulin signaling and reduced GLUT expression are directly involved in AD pathology,which causes neuronal and synaptic losses,memory deficits,and eventually death.However,several studies have demonstrated that restoration of brain insulin signaling and GLUT expression improved memory impairment in animal models (Niccoli et al.,2016;Chen et al.,2018;Das et al.,2019;Dubey et al.,2020).Thus,targeting the brain insulin signaling pathway or GLUTs may be a therapeutic strategy for AD treatment.

Icariin (ICA) is a major prenylated flavonoid found inEpimedium

spp.and bioactive component of the traditional Chinese herbal medicine Herba Epimedii,which is used clinically to treat osteoporosis and sexual dysfunction (Angeloni et al.,2019;Zeng et al.,2022).ICA has been shown to possess several pharmacological effects that include anti-AD,anti-tumor,anti-osteoporosis,and anti-inflammatory activities,and immune system modulation,cardiovascular protection,promotion of glucose metabolism,and neuroprotection (Angeloni et al.,2019;Jin et al.,2019;Qi et al.,2019;Li et al.,2020).Notably,the neuroprotective effects of ICA,particularly in amyloid precursor protein (APP)/presenilin 1 (PS1) transgenic mouse models of AD,have been extensively studied in our laboratory and are mechanistically mediated by antioxidation,promotion of nerve regeneration,activation of nitric oxide/cyclic guanosine monophosphate signaling,and decreased Aβ formation and tau hyperphosphorylation (Jin et al.,2014;Li et al.,2015,2019).However,the effects of ICA on the triple-transgenic mouse model of AD(3×Tg-AD),which is an ideal animal model of AD,and the mechanistic action of ICA on the defects of brain insulin signaling and decreased GLUTs have not been characterized.In this study,we explored whether ICA could protect against memory decline in 3×Tg-AD mice by reducing pathologic changes and reversing aberrant brain insulin signaling and reduction of GLUT expression.Methods

Animals

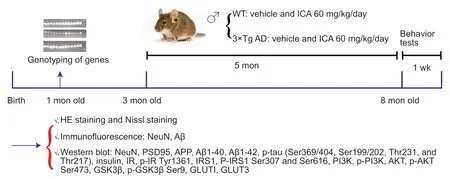

The 3×Tg-AD mice (Stock Number:034830-JAX,RRID:MMRRC_034830-JAX)with APP,PS1,and tau mutations and non-transgenic B6129SF2/J wild-type(WT) mice (Stock Number:101045,RRID:IMSR_JAX:101045) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor,ME,USA).The 3×Tg-AD and WT mice were coordinated to reproduce at the same time.Gene identification was performed at 1 month of age,and the 3-month-old male offspring,which were selected to avoid estrogen interference on learning and memory function (Xing et al.,2013),were used in the experimental study.All mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free animal room with food and waterad libitum

and a 12-hour light/dark cycle.The experimental procedures in this study are shown inFigure 1

.The 3×Tg-AD and WT mice were divided randomly into two groups each (n

=10/group),and then intragastrically administered either ICA or vehicle.All animal procedures were designed in accordance with the Chinese Guidelines of Animal Care and Welfare and performed under the supervision of the Animal Care and Use Committee of Zunyi Medical University (approval No.Lun Shen [2016] 2-089) on March 15,2016.

Figure 1 | Experimental scheme for this study.

ICA treatment

The 3×Tg-AD mice exhibit detectable Aβ accumulation at 3 months of age and tau accumulation at 6 months of age (Oddo et al.,2003;Hebda-Bauer et al.,2013);therefore,ICA (Cat# 140701,Nanjing Zelang Medicine Technology Co.,Ltd.,Nanjing,China) or vehicle treatment was begun at the age of 3 months.ICA was mixed with double-distilled water containing 0.5% Tween-80 and intragastrically administered at a dose of 60 mg/kg body weight daily for 5 months.The vehicle groups were intragastrically administered 0.1 mL doubledistilled water containing 0.5% Tween-80 per 10 g body weight in parallel.The animals were sacrificed 1 day after completion of the behavioral tests.Body weights were measured weekly during the treatment period.

Behavioral tests Open-field test

The open-field test was performed to examine any changes in exploratory and locomotor behavior of the animals (Huang et al.,2019).Each mouse was placed individually into a square open field (50 cm long,50 cm wide,and 50 cm high) and allowed to move and explore freely for 5 minutes.The spontaneous loci of mice in the central and peripheral areas were monitored using an animal tracking video system (WV-CP600/CH;Panasonic,Osaka,Japan) operated by computer software (Topscan 3.0;CleverSys Inc.,Reston,VA,USA).The total distance in 5 minutes and number of times the mice crossed the central and peripheral areas (line crossings) were analyzed.

Y maze alternation test

The Y maze test was used to examine memory ability (Liu et al.,2020).The maze consisted of three arms (34 cm long,8 cm wide,and 14.5 cm high) at 120° angles to each other.A mouse was placed into one of the arms to move freely for 5 minutes.The total number of arm entries were recorded using an automatic tracking system operated by computer software (Topscan 3.0),and the percentage of spontaneous alternations was calculated and analyzed according to the following formula:percentage of spontaneous alternation=number of alternations/(total arm entries– 2) × 100.

Brain tissue preparation

Three mice per group were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg;Sigma-Aldrich;Merk KGaA;Darmstadt,Germany) and transcardially perfused with 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline(PBS) followed by ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS.The brain tissue was separated,post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/0.1 M PBS for 48 hours at 4°C,dehydrated with a tissue processor (TP1020;Leica;Nussloch,Germany),and then embedded in conventional paraffin with a paraffinembedding machine (EG1150,Leica).The remaining mice were anesthetized as described above,and the entire cerebral cortex was quickly separated at 4°C and stored at–80°C until use for subsequent experiments.

Hematoxylin-eosin and Nissl staining

We referred to previously published experimental methods for hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and Nissl staining (Tian et al.,2013;Zong et al.,2016;Du et al.,2020).Briefly,the paraffin-embedded cerebral cortex was sliced into 5µm sections using a rotary microtome (RM2245,Leica),and the sections were dewaxed and rehydrated by using xylene solution and decreasing concentrations of ethanol solution,respectively.For HE staining,the sections were stained with hematoxylin solution (Solarbio,Beijing,China) for 15 minutes and eosin solution (Solarbio) for 5 minutes.For Nissl staining,the sections were incubated in 1% toluidine blue solution (Solarbio) for 30 minutes at 60°C to stain the neuronal Nissl bodies.The stained sections were rinsed with double-distilled water,dehydrated using progressively increasing concentrations of ethanol followed by xylene,and then cover slips were applied.The stained tissues were visualized using a light microscope (BX43;Olympus,Tokyo,Japan) to determine neuronal morphology (HE staining) and count surviving neurons (Nissl staining).

Immunofluorescent staining

Immunofluorescent staining was performed to assess Aβ deposits and the number of surviving neurons.In accordance with the method of Aboud et al.(Aboud et al.,2012),5 µm-thick cerebral cortex sections were dewaxed and rehydrated as described above and incubated with 3% hydrogen peroxide to exclude the influence of endogenous peroxidase.Antigen retrieval was performed using 0.1 M citrate buffer under high-temperature conditions after which the sections were blocked with goat serum (ZSGB-BIO,Beijing,China) at 37°C for 30 minutes.The sections were incubated at 4°C overnight with mouse anti-neuronal nuclear antigen (NeuN;1:100;Cell Signaling Technology,Danvers,MA,USA,Cat# 94403,RRID:AB_2904530) or rabbit anti-Aβ (1:500;Abcam,Cambridge,UK,Cat# ab201060,RRID:AB_2818982).After washing with PBS,the sections were incubated with the following secondary antibodies in the dark at 37°C for 1 hour:CoraLite488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:500;Proteintech,Wuhan,China,Cat# SA00013-2,RRID:AB_2797132) or fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-mouse (1:50;Proteintech Cat# SA00003-1,RRID:AB_2890896) antibodies.The sections were then stained with 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole at 37°C for 5 minutes.Finally,the tissues were visualized using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX41,Tokyo,Japan),and the fluorescent intensities were analyzed.

Western blot assay

To evaluate the expression of related proteins,western blots were performed as previously described (Huang et al.,2019).Briefly,the fresh cortex tissues of mice were homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing a general phosphatase and protease inhibitor cocktail.After a 12,000 ×g

centrifugation for 15 minutes at 4°C,the total protein concentration of the supernatant was measured using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Solarbio).Equal protein amounts were separated by 8–10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon-P;Millipore;Bradford,MA,USA).The membranes were blocked in 0.01 M Tris-HCl buffer containing 5% skim milk and 0.1% Tween-20 (pH 7.5) for 2–4 hours followed by incubation with primary antibodies (described below)overnight at 4°C.The blots were incubated with the following secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature:horseradish peroxidaseconjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:5000;Proteintech,Cat# SA00001-1,RRID:AB_2722565) or goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:5000;Proteintech,Cat#SA00001-2,RRID:AB_2722564).After three washes in 0.01 M Tris-HCl buffer containing 5% skim milk and 0.1% Tween-20,protein bands were visualized with enhanced electrochemiluminescence reagent (Tanon,Shanghai,China),and band intensities were analyzed using the ChemiDocimager system (Bio-Rad;Hercules,CA,USA).The primary antibodies used in this study were as follows:rabbit anti-insulin (1:1000;Proteintech,Cat# 15848-1-AP,RRID:AB_10597100),rabbit anti-insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1;1:1000;Proteintech Cat# 17509-1-AP,RRID:AB_10596914),mouse anti-GLUT1 (1:1000;Proteintech,Cat# 66290-1-Ig,RRID:AB_2881673),mouse anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (1:50,000;Proteintech,Cat# 60004-1-Ig,RRID:AB_2107436),mouse anti-NeuN (1:1000,described above),rabbit anti-insulin receptor (IR) beta-subunit (1:1000;Cell Signaling Technology,Cat# 3025S,RRID:AB_2280448),rabbit anti-p-IRS1 Ser307(1:1000;Cell Signaling Technology,Cat# 2381,RRID:AB_330342),rabbit anti-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K;1:1000;Cell Signaling Technology,Cat#4257,RRID:AB_659889),rabbit anti-phospho (p)-PI3K (1:1000;Cell Signaling Technology,Cat# 4228S,RRID:AB_659940),rabbit anti-protein kinase B (AKT;1:1000;Cell Signaling Technology,Cat# 9272S,RRID:AB_329827),rabbit anti-glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β;1:1000;Cell Signaling Technology,Cat# 9315,RRID:AB_490890),rabbit anti-p-GSK3β Ser9 (1:1000;Cell Signaling Technology,Cat# 9323,RRID:AB_2115201),rabbit anti-postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95;1:1000;Abcam,Cat# ab18258,RRID:AB_444362),rabbit anti-APP (1:2000;Abcam,Cat# ab32136,RRID:AB_2289606),rabbit anti-Aβ(1:1000;Abcam,Cat# ab201060,RRID:AB_2818982),rabbit anti-Aβ(1:1000;Abcam,Cat# ab110888,RRID:AB_10890827),rabbit anti-PHF1 antibody (recognizing p-tau Ser396/404;1:5000;Abcam,Cat#ab184951,RRID:AB_2861270),rabbit anti-p-tau Thr231 (1:5000;Abcam,Cat# ab151559,RRID:AB_2893278),rabbit anti-p-tau Ser199/202 (1:1000;Innovative Research,Cat# 44-768G,RRID:AB_1 502103;Thermo Fisher Scientific,Waltham,MA,USA),rabbit anti-p-tau Thr217 (1:1000;Innovative Research,Cat# 44-744,RRID:AB_1502121),rabbit anti-p-IR Tyr1361 (1:1000;Thermo Fisher Scientific,Cat# PA5-38283,RRID:AB_2554884),rabbit anti-p-IRS1 Ser616 (1:1000,Innovative Research,Cat# 44-550G,RRID:AB_1501245),rabbit anti-p-AKT Ser473 (1:1000;Affinity Biosciences,Zhenjiang,China,Cat# AF0016,RRID:AB_2810275),and rabbit anti-GLUT3 (1:1000;Affinity Biosciences,Cat# AF5463,RRID:AB_2837947).Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase antibody was used as a loading control.Statistical analysis

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes;however,our sample sizes are similar to those previously reported (Jin et al.,2014;Zong et al.,2016).No animals or data points were excluded from the analyses.The evaluators were blinded to the animal groupings.Quantitative and statistical analyses of the number of surviving neurons and protein band intensities were performed using Image Lab 5.2 (Bio-Rad) and SPSS 18.0 software (SPSS,Chicago,IL,USA),and the results were expressed as the means ± standard error of mean (SEM).One-way analysis of variance was used for all data that were obtained in this study,and the least significant difference test was used for pairwise comparisons between groups.AP

-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.At least three individual replicates were performed for each experiment.Results

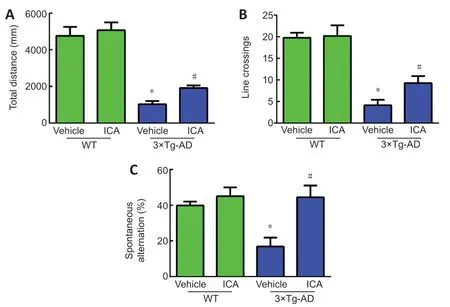

ICA significantly improves cognitive function of 3×Tg-AD mice Autonomous activity

To evaluate the effects of ICA on autonomous activities of 3×Tg-AD mice,an open-field test was conducted to determine exploratory and locomotor behavior.The total distances and line crossings by the 3×Tg-AD mice were markedly decreased compared with those in WT mice.ICA treatment observably increased the total distances and line crossings by the 3×Tg-AD mice,thus ameliorating their exploratory and locomotor behavior (Figure 2A

andB

).To investigate the effects of ICA on spatial recognition and memory ability of 3×Tg-AD mice,we performed the Y maze test.As shown inFigure 2C

,the percentage of spontaneous alternation was significantly decreased in the 3×Tg-AD+vehicle group compared with that in the WT+vehicle group.ICA treatment markedly increased the percentage of spontaneous alternation compared with that in the vehicle-treated 3×Tg-AD mice,indicating that ICA significantly improved the memory deficits of 3×Tg-AD mice.

Figure 2 | Effects of ICA on cognitive function in 3×Tg-AD mice.

ICA significantly attenuates the pathological injury in the cerebral cortex of 3×Tg-AD mice

To investigate whether ICA alleviated histopathological changes in 3×Tg-AD mice,we performed HE and Nissl staining to observe the pathological changes and number of neurons in the cerebral cortex.HE staining showed that cerebral neurons in the WT mice exhibited regular arrangement with distinct edges and clear nuclei and nucleoli (Figure 3A

).However,in the 3×Tg-AD +vehicle group,cerebral neurons displayed an irregular arrangement,structural ambiguity,nuclear shrinkage,and deep staining,which was significantly ameliorated by ICA treatment (Figure 3A

).Additionally,Nissl staining demonstrated a significant loss of cerebral neurons in the 3×Tg-AD+vehicle group compared with that in WT mice.ICA treatment markedly promoted the survival of cerebral neurons compared with that in the vehicle-treated 3×Tg-AD mice (Figure 3A

andB

).To further confirm the neuroprotective effect of ICA,the number of NeuNpositive cells and NeuN protein expression levels were used to evaluate the effects of ICA on neurons in the cerebral cortex.NeuN is a neuronal marker for mature neurons (Mullen et al.,1992).As shown inFigure 3C–E

,ICA treatment observably increased the number of NeuN-positive neurons and NeuN protein levels compared with those in the 3×Tg-AD+vehicle group.Synapse loss is a pathological basis of memory dysfunction (Asok et al.,2019),and PSD95,which is a synaptic marker (Coley and Gao,2018),was used to evaluate the effects of ICA on synapse integrity.As expected,ICA treatment of 3×Tg-AD mice observably increased PSD95 expression compared with that in the 3×Tg-AD+vehicle group (Figure 3D

andE

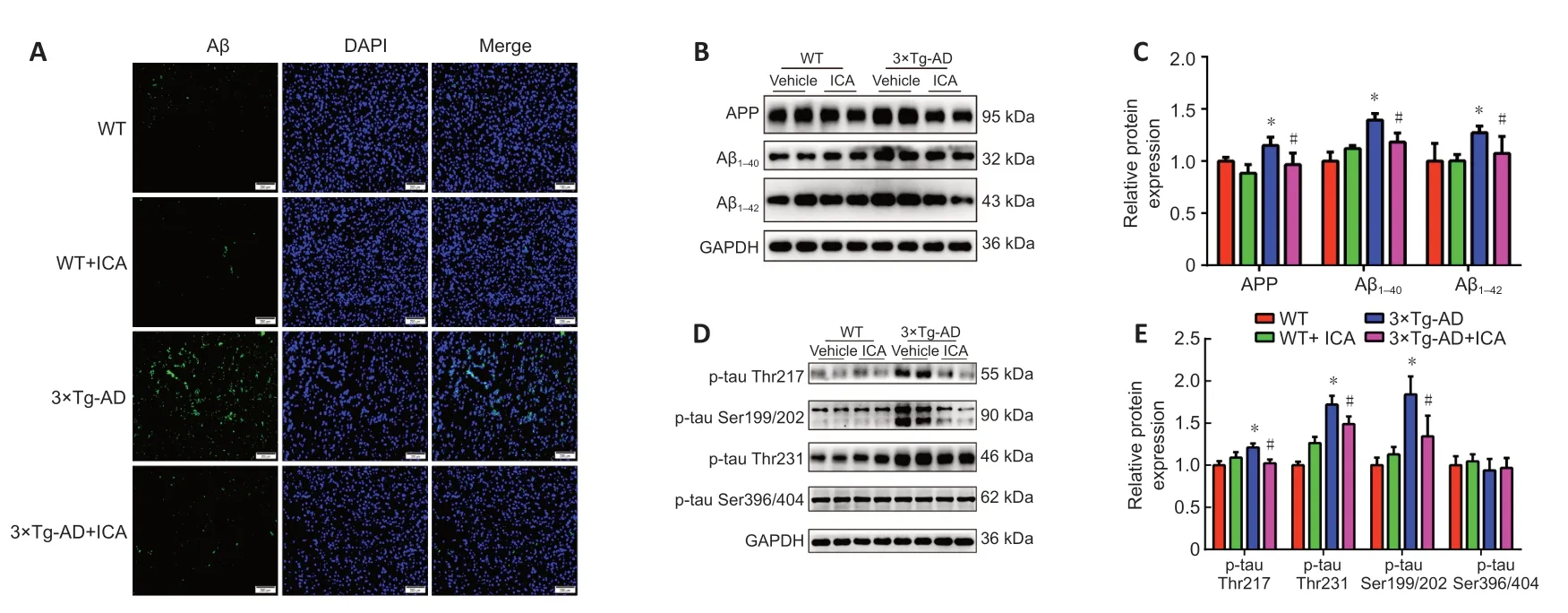

).These results showed that ICA treatment protected neurons and synapses from damage in 3×Tg-AD mice.ICA significantly reduces pathological Alzheimer’s markers in the cerebral cortex of 3×Tg-AD mice

To explore whether the neuroprotective effect of ICA in 3×Tg-AD mice was achieved by the amelioration of AD markers,Aβ accumulation and tau hyperphosphorylation in the cerebral cortex were evaluated.Treatment with ICA markedly attenuated Aβ accumulation in the cerebral cortexes of 3×Tg-AD+ICA mice compared with that in the 3×Tg-AD+vehicle group (Figure

4A

).To confirm these results,we performed western blot analysis to assess ICA-mediated modulation of Aβ deposits.A significant decrease in levels of the Aβ peptide precursor APP and Aβand Aβpeptides,both of which are the main components of senile plaques (SPs) (Seino et al.,2021),was observed in the 3×Tg-AD+ICA group compared with those in the 3×Tg-AD +vehicle group (Figure 4B

andC

).The accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau in AD brain is another important pathological hallmark,and more than 40 hyperphosphorylated sites have been documented (Kimura et al.,2018),including Thr217,Ser199/202,Thr231,and Ser396/404.In the present study,ICA treatment markedly decreased hyperphosphorylated tau at the Thr217,Ser199/202,and Thr231 sites when compared with that in the 3×Tg-AD +vehicle group (Figure 4D

andE

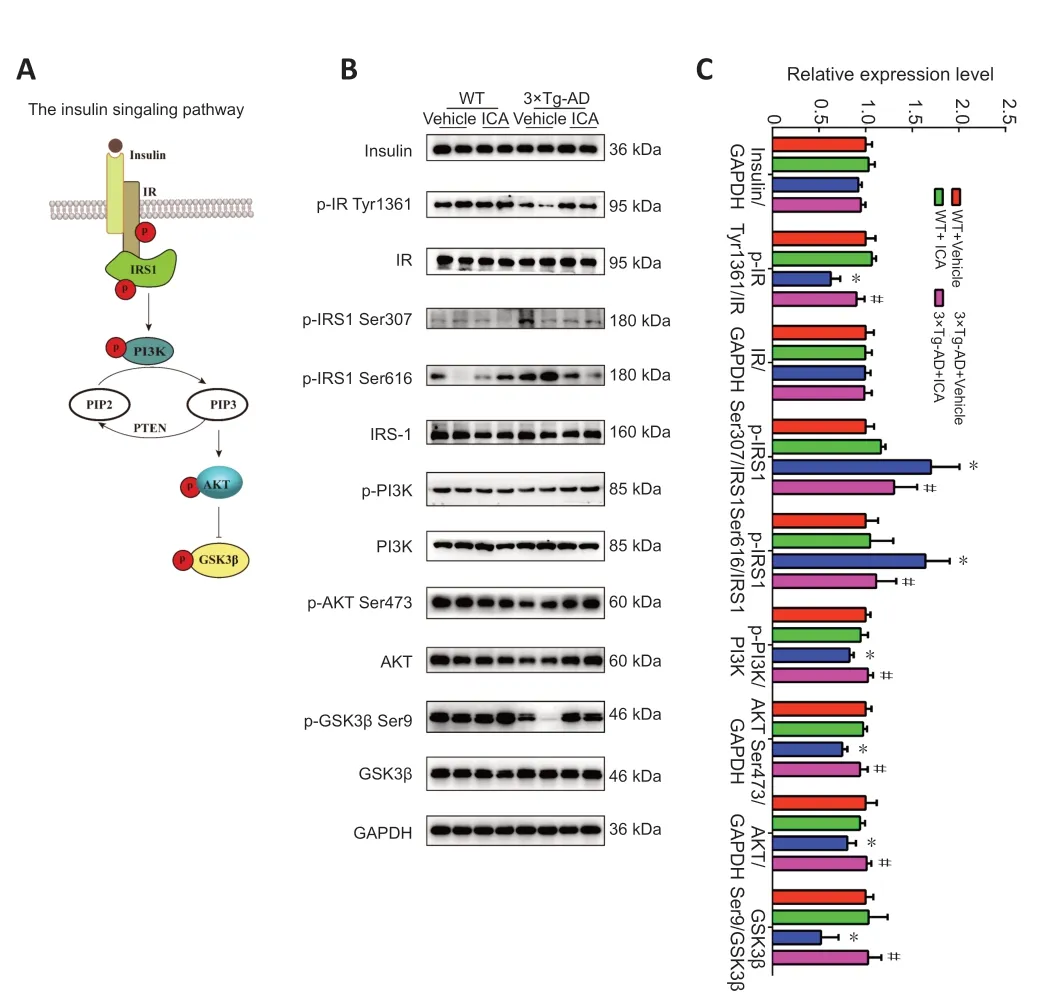

).These results suggested that ICA alleviated AD-like pathology in 3×Tg-AD mice.ICA improves brain insulin resistance by restoring impaired insulin signaling in the cerebral cortex of 3×Tg-AD mice

The insulin signaling pathway is shown inFigure 5A

and plays a vital role in memory function and aging;a disordered insulin signaling pathway has been shown to contribute to AD pathogenesis (Gabbouj et al.,2019).The protein levels of insulin and the IR did not change significantly among the four mouse groups (Figure 5B

andC

).However,the expression of phosphorylated IR at Tyr1361 was significantly reduced in the vehicle-treated 3×Tg-AD,and ICA treatment significantly reversed this decline (Figure 5B

andC

).Increased phosphorylation levels at serine residues of IRS1,which is a substrate of the IR tyrosine kinase,is an important indicator of cerebral insulin resistance (Talbot et al.,2012).As shown inFigure 5B

andC

,elevated levels of phosphorylated IRS1 at Ser307 and Ser616 were observed in the 3×Tg-AD+vehicle group compared with those in both WT groups,and this elevation was reversed in 3×Tg-AD mice by ICA treatment.Next,we determined the expression levels of related proteins in the insulin signaling pathway.We found that p-PI3K,p-AKT Ser473,AKT,and p-GSK3β Ser9 were downregulated in the 3×Tg-AD+vehicle group compared with those in both WT groups,and ICA treatment of 3×Tg-AD mice increased the expression levels of these proteins (Figure 5B

andC

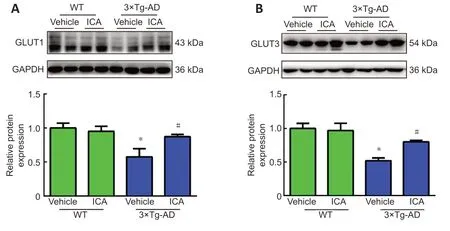

).These results indicated that ICA ameliorated cerebral insulin resistance in 3×Tg-AD mice by restoring phosphorylation status and expression levels of molecules related to the insulin signaling pathway.ICA increases the expression of GLUT1 and GLUT3 in the cerebral cortex of 3×Tg-AD mice

Decreased expression of GLUTs in the AD brain is correlated with memory impairment.Therefore,we evaluated the expression of GLUT1 and GLUT3,which are two major GLUTs in the brain (Koepsell,2020).Western blots showed that the expression levels of GLUT1 and GLUT3 were significantly downregulated in the 3×Tg-AD+vehicle group compared with those in the WT+vehicle group,while ICA treatment increased their expression levels in 3×Tg-AD mice (Figure 6A

andB

).These results suggested that ICA-mediated upregulation of GLUT1 and GLUT3 expression may play a role in ameliorating memory deficits.

Figure 3 | Effects of ICA on the pathological injury in the cerebral cortex of 3×Tg-AD mice.

Figure 4 | Effects of ICA on AD-like pathology in the cerebral cortex of 3×Tg-AD mice.

Figure 5 | Effects of ICA on impaired insulin signaling in the cerebral cortex of 3×Tg-AD mice.

Figure 6 | Effects of ICA on glucose transporters in the cerebral cortex of 3×Tg-AD mice.

Discussion

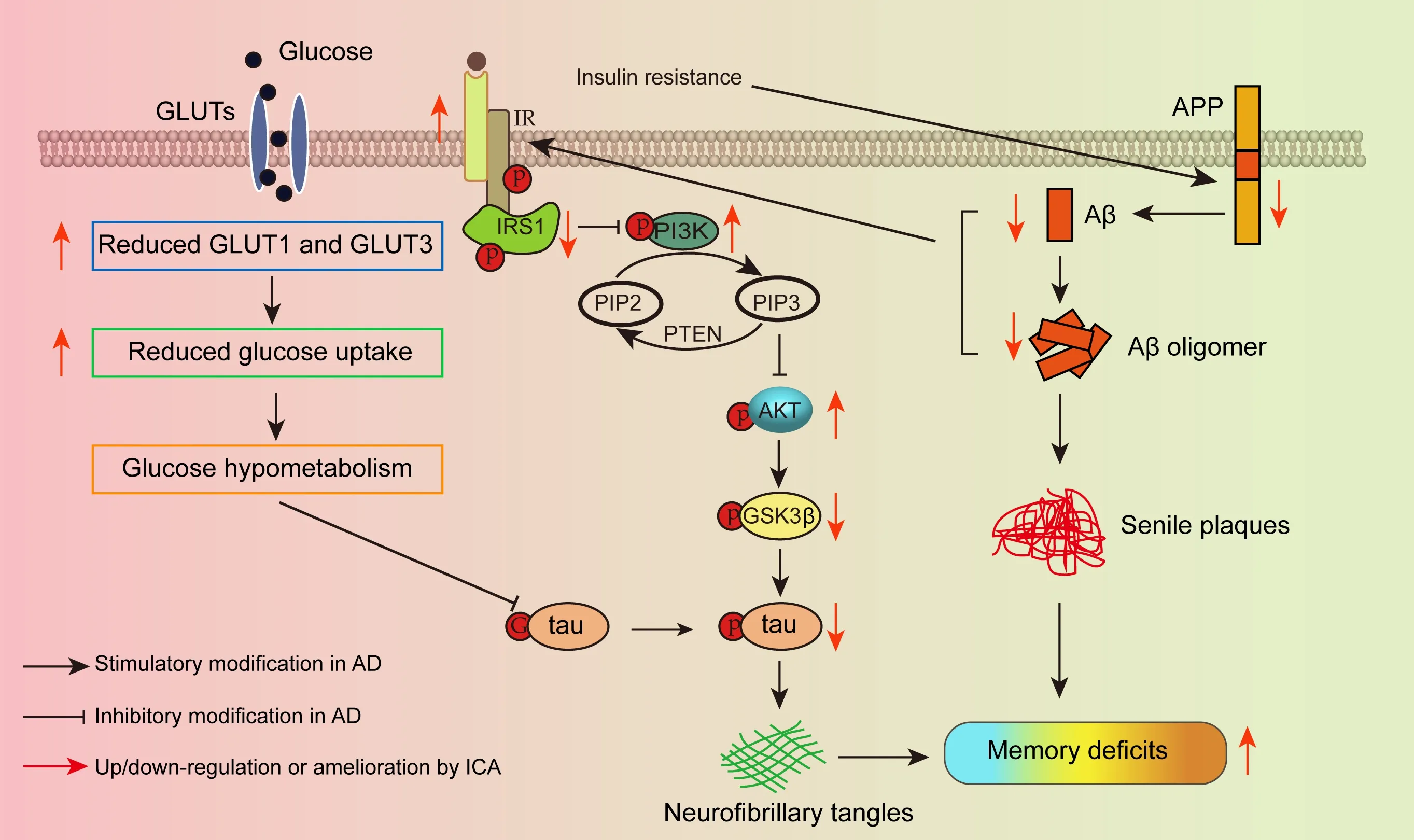

AD is the most prevalent form of dementia,which manifests as progressive damage to memory function.AD afflicts over 50 million people worldwide,and the incidence increases with age (Hodson,2018).Neuropathologically,AD has characteristic features,such as SPs composed of Aβ,neurofibrillary tangles formed by hyperphosphorylated tau,synaptic loss,and neuronal death in the brain,especially in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus (Fjell et al.,2014;DeTure and Dickson,2019).However,there is currently no diseasemodifying drug treatment available for AD (Vaz and Silvestre,2020).Impaired insulin signaling in the brain is one of the most critical factors in AD and is associated with decreased glucose metabolism and AD pathology including Aβ accumulation,tau hyperphosphorylation,and loss of neurons and synapses,which can lead to memory impairment and,ultimately,death.In the present study,impaired insulin signaling and reduced GLUTs were observed in the cerebral cortex of 3×Tg-AD mice.ICA reversed these changes,thereby inhibiting Aβ accumulation and tau phosphorylation,alleviating the damage to neurons and synapses,and ameliorating memory deficits (Figure 7

).

Figure 7 | Schematic diagram of the mechanism by which ICA regulates GLUTs and brain insulin signaling to ameliorate memory impairment in AD.

In the present study,amelioration of memory was measured,and we further assessed the beneficial effects of ICA on AD histopathology in 3×Tg-AD mice.The results revealed that ICA ameliorated damage to neurons and Nissl bodies,which are associated with protein synthesis in neurons (Palay and Palade,1955).In addition,we examined NeuN and PSD95,which are markers of neurons and synapses,respectively (Mullen et al.,1992;Coley and Gao,2018).These results suggested that ICA treatment reduced both neuronal and synaptic losses and,consequently,inhibited neurodegeneration in the cerebral cortex of 3×Tg-AD mice.

SPs and tau hyperphosphorylation are two classic pathological features of AD.SPs occur through the stepwise formation of Aβ monomers,oligomers,and finally fibrils (Schmit et al.,2011;Potapov et al.,2015).Therefore,Aβ,which is formed by hydrolysis of APP,is thought to be an initial pathological abnormality in AD,and Aβand Aβare among the most abundantly generated Aβ isoforms (Castellani et al.,2019).Our experimental studies indicated that ICA treatment improved Aβ pathology by significantly reducing the levels of APP,Aβ,and Aβ.Hyperphosphorylated tau triggers the formation of neurofibrillary tangles and is the second essential lesion that has a greater association with memory impairment than SPs (Bierer et al.,1995;Mamun et al.,2020).Our results indicated that ICA inhibited tau hyperphosphorylation at Thr217,Ser199/202,and Thr231,but not Ser396/404,thus ameliorating tau pathology.Taken together,the amelioration of Aβ and tau pathology via ICA may have protected against memory dysfunction in 3×Tg-AD mice,suggesting that ICA exerted a therapeutic effect in the 3×Tg-AD mouse model.

Because strong evidence supports the correlation between insulin signaling and brain function,the role of brain insulin signaling in memory disorders,such as AD,has received widespread attention (Soto et al.,2019;Akhtar and Sah,2020;Shieh et al.,2020).IR autophosphorylation at tyrosine residues occurs via the binding of insulin to the IR,which then exerts its tyrosine kinase activity (Akhtar and Sah,2020).However,it has been reported that desensitized IR and reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of the IR occur in AD (Xie et al.,2002;Zhao et al.,2008).In agreement with the literature,in the present study,we found that phosphorylation of the IR at Tyr1361 was significantly decreased in 3×Tg-AD mice and was remarkably reversed by ICA treatment,suggesting the restoration of IR sensitivity to insulin.However,we found no significant differences in the insulin protein levels in the cerebral cortexes among the four groups,although significant alterations in insulin levels were observed in the cleared serum of Aβ-induced AD rats (Athari Nik Azm et al.,2017).Furthermore,no changes in IR protein levels were observed among the four groups.This may be because of differences between experimental AD models as well as in the age and sex of the animals (Zhao et al.,2008;Chen et al.,2014).Nevertheless,further experiments should be performed to confirm IR internalization and expression on the cell membrane to define the role of impaired insulin signaling in the pathogenesis of AD.

The binding of insulin triggers IRS1 phosphorylation at tyrosine residues,which is a positive regulatory mechanism that activates the PI3K/AKT pathway(Tanokashira et al.,2019).In contrast,IRS1 is negatively regulated by serine phosphorylation at Ser307 and Ser616,and phosphorylation at these sites is significantly increased in AD,which may lead to insulin resistance (Talbot et al.,2012).Our results distinctly revealed that ICA treatment decreased IRS1 phosphorylation at Ser307 and Ser616 residues in 3×Tg-AD,thus potentially alleviating brain insulin resistance of the AD mice.After insulin stimulation,IRS1 recruits and activates PI3K/AKT,resulting in PI3K and AKT phosphorylation followed by GSK3β phosphorylation at Ser9 and inhibition of GSK3β activity (Akhtar and Sah,2020).Accordingly,IRS1 dysfunction leads to dephosphorylation and inhibition of the PI3K/AKT pathway as well as the dephosphorylation and activation of GSK3β.In the present study,ICA treatment increased the expression of phosphorylated PI3K,AKT,and phosphorylated AKT at Ser473,suggesting activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway.Additionally,ICA treatment increased GSK3β phosphorylation at Ser9,which inhibits GSK3β activity.These results collectively suggest that ICA improves memory impairment of 3×Tg-AD mice via modulation of the brain insulin signaling pathway (IR/IRS1/PI3K/AKT/GSK3β).

Studies have shown that,because of increased secretase activity or decreased activity of the insulin-degrading enzyme (a major Aβ hydrolase),impaired brain insulin signaling promotes the formation of Aβ plaques by increasing Aβ production or reducing Aβ clearance (Lee et al.,2003;Ho et al.,2004;Kim et al.,2019).Additionally,it is well known that impaired brain insulin signaling is associated with hyperphosphorylated tau.For example,the activation of GSK3β,which is a crucial tau kinase,has been reported to mediate tau hyperphosphorylation through the modulation of the insulin/PI3K/AKT pathway (Zhang et al.,2018).Consequently,brain insulin signaling is further damaged by Aβ accumulation and tau hyperphosphorylation.Toxic Aβ monomers or oligomers have been shown to trigger brain insulin signaling defects by binding to or degrading the IR (Xie et al.,2002;Zhao et al.,2008;Gali et al.,2019).In addition,the lack of tau promotes abnormal brain insulin signaling that is related to changes in energy metabolism,which contributes to cognitive and metabolic disorders in AD patients (Marciniak et al.,2017).Taken together,impaired insulin signaling,Aβ pathology,and tau pathology accelerate the development of pathological deterioration in AD.However,ICA may be useful as a therapeutic agent to improve AD pathology and symptoms.GLUTs are responsible for glucose transport from the blood to the braintissue and are associated with memory impairment in AD (Koepsell,2020).Reduced GLUT levels have been demonstrated in AD and result in decreased glucose uptake,glucose hypometabolism,energy metabolism disorders,neurodegeneration,and the corresponding symptoms of AD (Winkler et al.,2015;Wu et al.,2019).Here,we focused on two major GLUTs present in the brain,GLUT1 and GLUT3,which transport glucose from the bloodstream to the extracellular space and neurons,respectively (Qutub and Hunt,2005).It has been reported that GLUT1 and GLUT3 deficiency contributes to the decline in brain glucose uptake and metabolism and neurodegeneration via downregulation of tau O-GlcNAcylation (G-tau) and hyperphosphorylation of tau in AD (Liu et al.,2008).ICA treatment may have increased brain glucose uptake via inhibition of tau hyperphosphorylation and increasing levels of GLUT1 and GLUT3,which improved memory deficits of the 3×Tg-AD mice.

Some limitations exist in our study.This study was only performed in animals,and noin vitro

experiments were designed to further study the specific mechanism of ICA.For the evaluation of learning and memory function,only the Y maze test was performed,and the classical Morris water maze test was not used.In summary,we provide evidence that ICA treatment ameliorated impairments of brain insulin signaling and increased the expression of glucose transporters and impeded the formation of pathogenic Alzheimer’s proteins,such as Aβ accumulation and hyperphosphorylated tau.ICA treatment protected neurons and synapses against disordered brain insulin signaling and glucose hypometabolism and improved memory impairment in the AD mice.The low toxicity icariin may bring new hope for AD patients,and our research lays the foundation for the follow-up study of icariin in the prevention and treatment of AD.

Acknowledgments:

We are deeply grateful to all members of the Key Laboratory of Basic Pharmacology of Ministry of Education and Joint International Research Laboratory of Ethnomedicine of Ministry of Education,Zunyi Medical University.

Author contributions:

Study design,manuscript revision,and supervision:JSS,SYZ,FJ;experiment implementation,data analysis and manuscript draft:FY,JL;experimental assistance:MXC,YZ,SJW,HJ;discussion assistance:JN,XLF.All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Availability of data and materials:

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Open access statement:

This is an open access journal,and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License,which allows others to remix,tweak,and build upon the work noncommercially,as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Open peer reviewers:

Alessandro Castorina,University of Technology Sydney,Australia;Marta Valenza,Sapienza University of Rome,Italy;Ahmed Abdel-Zaher,Assiut University,Egypt.

Additional file:

Open peer review reports 1 and 2.

- 中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Neuroaxonal and cellular damage/protection by prostanoid receptor ligands,fatty acid derivatives and associated enzyme inhibitors

- Extracellular vesicles in Alzheimer’s disease:from pathology to therapeutic approaches

- Molecular approaches for spinal cord injury treatment

- Sex-biased autophagy as a potential mechanism mediating sex differences in ischemic stroke outcome

- Adipose tissue,systematic inflammation,and neurodegenerative diseases

- Interleukin-1:an important target for perinatal neuroprotection?