基于加权基因共表达网络分析识别抑郁症的差异表达基因模块

耿瑞杰,姚 琳,黄欣欣,禹顺英,苑成梅,洪 武,吕钦谕,王庆中,易正辉#,方贻儒,5,6

1.复旦大学附属中山医院心理医学科,上海200032;2.上海交通大学医学院附属精神卫生中心精神科,上海200030;3.上海市浦东新区南汇精神卫生中心精神科,上海201399;4.上海中医药大学中药研究所神经药理实验室,上海201203;5.中国科学院脑科学与智能技术卓越创新中心,上海200031;6.上海市重性精神病重点实验室,上海201108

抑郁症(major depressive disorder,MDD)是一种常见的精神疾病,具有高患病率、高致残率、疾病负担沉重等特点[1-4]。目前其病因及发病机制未明,尚无明确的实验室检测指标可用于诊断及预后。既往研究[5-8]提示抑郁症有显著的遗传易感性,并且受心理与环境的影响,遗传与环境的交互作用是抑郁症发病的主要因素。

双生子研究[9]显示抑郁症的遗传度约为37%,异卵双生子的发病一致率为20%,同卵双生子的发病一致率约为40%。家系研究[9]提示抑郁症在家族中呈聚集现象,患者一级亲属的患病率是正常人的2~3倍。全基因组关联分析(genome wide association study,GWAS)表明,抑郁症的遗传性主要是通过常见的单核苷酸多态性(single nucleotide polymorphism,SNP)来解释。然而直至目前,在一般人群中鉴定与抑郁症相关的基因仍未取得显著成效[10]。有研究[11]分别在抑郁症首发阶段分析18 759 例患者的120万个常染色体和X 染色体的SNP,在抑郁症复发阶段分析6 783 个病例及50 695 个健康对照的554 个常染色体SNP,其结果显示没有SNP同时在抑郁症的2个阶段达到全基因组水平上的显著性。Hyde 等[12]使用来自75 607 例抑郁症患者和231 747 个健康对照者的自我报告数据,并对这些结果与已发表的抑郁症全基因组关联研究结果进行了meta分析;结果表明15个区域的17个独立SNP 达到了全基因组水平上的显著性。此外,一些针对抑郁症患者血液基因表达谱的微阵列的研究和RNA 测序(RNA-seq) 研究也鉴定了许多差异表达基因(differentially expressed gene,DEG)[13-16];然而报道的DEG 在各项研究中差异较大,一项研究中鉴定出的大部分DEG 未能在其他研究中被重复获得。虽然抑郁症遗传度较高,但是目前研究结果不甚理想:一方面可能是因为抑郁症是遗传与环境共同作用所致;另一方面,一些复杂疾病,特别是精神疾病,不是由单一基因起主要作用而是由许多微效基因共同作用的结果[17]。仅仅对单个基因功能水平的研究已经限制了我们探索抑郁症分子机制的进程,而通过构建基因网络,从系统层面分析基因之间的相互作用成为下一步的研究热点。加权基因共表达网络分析 (weighted gene co-expression network analysis,WGCNA)是构建基因共表达网络的代表性方法,它基于无尺度拓扑结构进行相似性度量和设定阈值,方法更具合理性并且已成功地应用到多个研究领域。

1 对象与方法

1.1 研究对象

mRNA微阵列数据来自本课题组前期已经完成的8例抑郁症患者及8名健康对照者(对照组)的外周血mRNA微阵列分析实验[18]。入组病例均为上海市精神卫生中心精神科门诊和心理咨询门诊的患者,以及心境障碍科住院患者。抑郁症患者年龄(34.9±9.8)岁,已婚5 例,未婚3 例;对照组年龄(35.4±10.2)岁,已婚5 例,未婚3例。入组时抑郁症患者汉密尔顿抑郁量表(Hamilton Depression Scale,HAMD)总分平均(22.75±3.54)分;对照组为上海市精神卫生中心职工及学生。病例组及对照组之间无血缘关系。

1.2 研究方法

1.2.1 DEG 的筛选 应用t检验统计方法筛选抑郁症患者与对照组的DEG[19],其中差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)的基因被纳入后续的分析。

1.2.2 WGCNA 通过R 软件中的WGCNA 包进行分析。通过计算每组基因的相似矩阵、邻接矩阵、拓扑重叠矩阵,衡量节点间相异度等步骤绘制层次聚类树(树状图)。按照WGCNA 原理中无尺度网络原则选择邻接函数的加权参数β。将关联系数阈值设定为0.9(此时参数β=14)来构建基因数据集的共表达网络(图1)。应用混合动态树切割方法来切割分支,完成初步的模块构建后将基因较少的模块进行合并。

1.2.3 模块-表型关联和枢纽基因的鉴定 通过Pearson相关性分析评估上一步检测到的模块与抑郁症之间的相关性。模块eigengene(module eigengene,ME)是指给定模块的第一主成分,代表整个模块的基因表达谱。分别选取ME与抑郁症正相关性和负相关性最强(相关系数绝对值最大)的2个模块作为后续研究的候选模块。这一步计算基于基因显著性(gene significance,GS)、模块身份(module membership, MM) 和模块内连接性(intramodular connectivity)。本研究中,GS的定义为基因和抑郁症之间相关系数的绝对值;MM 的定义为ME与基因表达谱的相关性。每个基因的模块内连接性(连接值之和除以模块内基因的数量)用kWithin 值表示。具有高GS、高MM,且模块内连接性从高到低排名前3 位的基因被定义为模块的枢纽基因[20],然后利用R 软件中的igraph和qgraph包绘制模块内基因相互作用网络。

1.2.4 基因功能富集和网络分析 利用metascape在线网站对候选模块进行GO 功能富集分析和KEGG 通路分析(http://metascape.org/gp/index.html),计算出与富集基因功能相关生物学过程和信号通路。P值的计算基于超几何分布检验,P<0.05被认为具有统计学意义。

2 结果

2.1 数据预处理和DEG筛选

mRNA 微阵列数据经预处理后,从16 个样品中获得54 675 个基因的表达矩阵,比较抑郁症患者和正常对照组,按P<0.05 的条件共得到4 125 个DEG 用于下一步研究。

2.1.1 加权基因共表达网络的构建 按照WGCNA 原理中无尺度网络原则选择邻接函数的加权参数β,采用WGCNA 中的step-by-step 法,完成基因共表达网络的构建(图1)。共识别出9 个mRNA 基因模块,每个基因模块包含195~696个基因,每个模块用不同的颜色代替,用灰色表示无法合并到任何模块的基因。

图1 基因聚类树Fig 1 Dendrogram of gene clustering

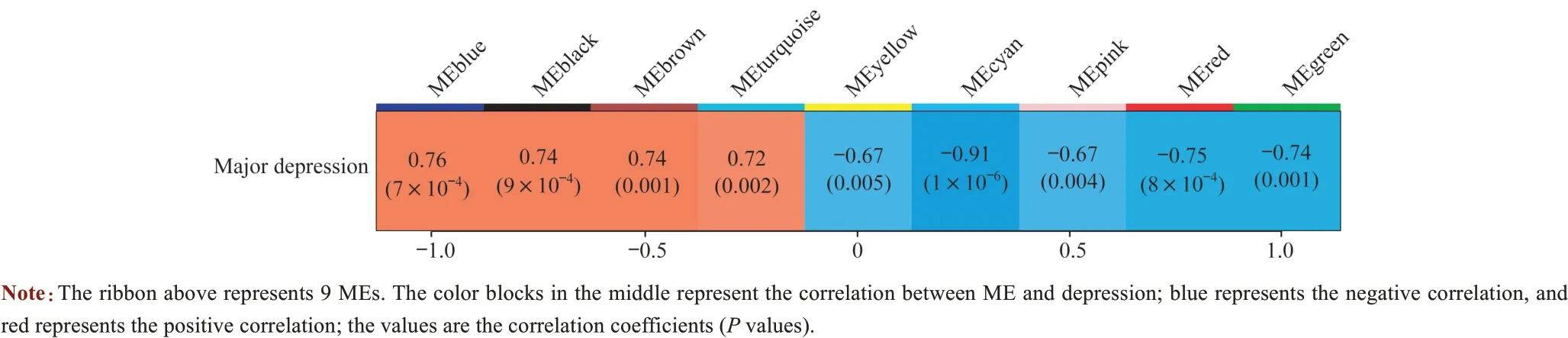

2.1.2 基因模块与抑郁症的相关性 计算9 个模块的ME与抑郁症的相关性(图2),结果可见这9 个模块均与抑郁症呈显著关联。其中绿色(green)、红色(red)、黄色(yellow)、粉色(pink)、青色(cyan)模块与抑郁症之间呈负相关;cyan 模块的负相关性最高,相关系数为-0.91(P=0.000)。蓝绿色(turquoise)、棕色(brown)、黑色(black)、蓝色(blue)这4 个模块与抑郁症呈正相关;blue 模块正相关性最强,相关系数为0.76 (P=0.000)。因此,选取cyan 模块和blue 模块作为候选模块进行下一步研究。

2.2 从候选模块中识别枢纽基因并构建基因网络

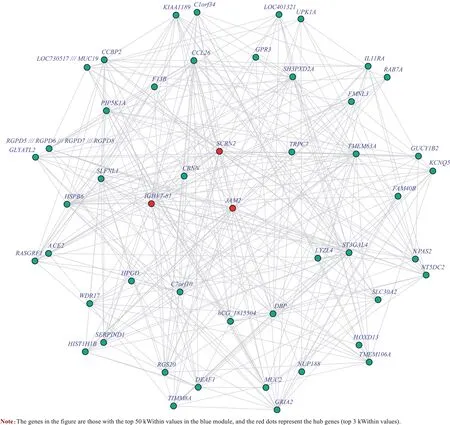

计算每个基因的模块内连接性(kWithin 值),选取2个模块中kWithin值最高的前50个基因,绘制基因相互作用图。将2 个模块中kWithin 值最高的前3 个基因认定为枢纽基因。Blue 模块的枢纽基因为JAM2(junctional adhesion molecule 2)、SCRN2(secernin 2)和IGHV7-81(immunoglobulin heavy variable 7-81);cyan 模块的枢纽基因为SCFD2(Sec1 family domain containing 2)、NR5A2(nuclear receptor subfamily 5 group A member 2) 和KCNMA1(potassium calcium-activated channel subfamily M alpha 1)。如图3 和图4 所示,所有的枢纽基因具有网络中相邻基因的紧密连接性。

图2 9个基因模块的ME与抑郁症的关联图Fig 2 The association between 9 MEs of gene modules and depression

图3 Blue模块的基因相互作用网络Fig 3 Gene interaction network of the blue module

图4 Cyan模块基因相互作用网络Fig 4 Gene interaction network of the cyan module

2.3 模块基因的功能注释和通路分析

利用metascape 对blue 模块和cyan 模块进行功能注释和通路分析,结果提示cyan 模块没有富集到有统计学意义的KEGG 通路,blue 模块的KEGG 通路则富集到3 条,分别为RNA 转运、沙门菌感染和黑色素生成(图5A)。Cyan 模块共富集到GO 条目20 条,其中15 条与胚胎发育及细胞生长、凋亡有关,2 条与细胞周期有关,1 条与物质运输相关;值得注意的是有1 条GO 条目为通过质膜黏附分子的嗜同性细胞黏附(GO:0007156),与免疫及炎症反应有关;另有1条为跨膜受体蛋白酪氨酸激酶信号通路(GO:0007169),与细胞信号转导有关。Blue 模块共富集到15 条GO 条目,其中7 条与物质加工转运有关(图5B)。

图5 Blue模块和cyan模块的生物注释Fig 5 Biological annotation of blue module and cyan module

3 讨论

WGCNA 软件的算法是基于样本之间表达谱的相似性来构建基因共表达网络,以此对基因表达信息进行系统层面的描述分析。相对于传统差异表达分析仅仅对单个基因功能水平进行研究,WGCNA 共表达网络主要基于系统论,充分考虑到生命体的复杂性以及基因和基因之间的高阶交互作用,可以揭示转录组系统层面的表达改变。WGCNA 已经在多种疾病中广泛应用,如肿瘤、帕金森病、孤独症等。在本研究中,我们利用WGCNA共识别出9个基因模块,挑选出其中与抑郁症正相关性和负相关性最强的2 个模块,这2 个模块的生物功能注释提示免疫和炎症反应可能在抑郁症的发生、发展中发挥一定作用。既往许多研究[21-28]发现,炎症反应是一种重要的生物学反应,可能会增加重度抑郁发作的风险。最近,Wang 等[29]发现相比健康对照人群,肿瘤坏死因子-α(tumor necrosis factor α,TNF-α)在抑郁症死亡患者的脑组织背外侧前额叶皮质和外周血中的表达量更高,提示抑郁症患者体内可能存在促炎细胞因子失调。此外,已有临床研究[30-31]报道了TNF-α 特异性单克隆抗体对治疗抑郁症具有良好的效果。因此,炎症反应可能在抑郁症的发病机制中起关键作用。

在blue 模块和cyan 模块中共识别出6 个枢纽基因,即JAM2、SCRN2、IGHV7-81(blue 模块),以及SCFD2、NR5A2、KCNMA1(cyan 模块)。有证据提示JAM2、SCFD2、NR5A2和KCNMA1与抑郁症之间存在一定的相关性。首先,根据CTD Gene-Disease Associations 数据库可以检索到JAM2、NR5A2、KCNMA1和抑郁症显著相关,标准值分别为1.27、1.81 和1.37;GWASdb SNPPhenotype Associations数据库也提示NR5A2、KCNMA1和抑郁症显著相关,标准值分别为0.75 和0.61。Yi等[18]通过全基因组cRNA 微阵列研究发现SCFD2在抑郁症患者中的表达显著低于健康对照,差异倍数(fold change)为0.72(P<0.001)。另有研究[32]发现,KCNMA1与孤独症谱系障碍(autistic spectrum disorder,ASD)和癫痫综合征均有一定的关联;而ASD 和癫痫常常与抑郁症之间存在共病现象,ASD 患者抑郁症的患病率明显较高[33],提示KCNMA1基因也可能在抑郁症的发病中起作用。因此,我们认为JAM2、SCFD2、NR5A2、KCNMA1与抑郁症之间存在相关性的可能性较大,这也从另一方面说明WGCNA 筛选枢纽基因的可靠性。至于另外2 个基因SCRN2和IGHV7-81,我们暂未发现确切的证据证明其与抑郁症的相关性,但并不能排除这一可能性。

本研究也存在一定的局限性。首先,抑郁症的临床表现具有多样性的,本研究未对抑郁症的临床表现进行分类并分别分析其与基因模块之间的相关性。其次,由于本研究的样本量较小,WGCNA 分析的统计效能较低。R 软件的pwr 包分析显示,当效应量设置为0.7 时,统计效能仅为0.74(小于0.8)。后续研究需要增加样本量以进一步验证本研究的发现,并探索这些枢纽基因在抑郁症的病理生理过程中的潜在作用机制。

参·考·文·献

[1] Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication(NCS-R)[J]. JAMA,2003,289(23):3095-3105.

[2] Labonté B,Engmann O,Purushothaman I,et al. Sex-specific transcriptional signatures in human depression[J]. Nat Med,2017,23(9):1102-1111.

[3] Mandelli L,Serretti A. Gene environment interaction studies in depression and suicidal behavior: an update[J]. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2013, 37(10 Pt 1):2375-2397.

[4] Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010[J]. PLoS Med,2013,10(11):e1001547.

[5] Hing B, Sathyaputri L, Potash JB. A comprehensive review of genetic and epigenetic mechanisms that regulate BDNF expression and function with relevance to major depressive disorder[J]. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet,2018,177(2):143-167.

[6] Hoffmann A, Sportelli V, Ziller M, et al. Epigenomics of major depressive disorders and schizophrenia:early life decides[J]. Int J Mol Sci,2017,18(8):E1711.

[7] de Sousa RT, Loch AA, Carvalho AF, et al. Genetic studies on the tripartite glutamate synapse in the pathophysiology and therapeutics of mood disorders[J]. Neuropsychopharmacology,2017,42(4):787-800.

[8] Klengel T, Binder EB. Gene-environment interactions in major depressive disorder[J]. Can J Psychiatry,2013,58(2):76-83.

[9] Sullivan PF, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis[J]. Am J Psychiatry, 2000, 157(10):1552-1562.

[10] Nishino J, Ochi H, Kochi Y, et al. Sample size for successful genome-wide association study of major depressive disorder[J]. Front Genet, 2018,9:227.

[11] Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric GWAS Consortium. A mega-analysis of genome-wide association studies for major depressive disorder[J]. Mol Psychiatry,2013,18(4):497-511.

[12] Hyde CL, Nagle MW, Tian C, et al. Identification of 15 genetic loci associated with risk of major depression in individuals of European descent[J]. Nat Genet,2016,48(9):1031-1036.

[13] Menke A, Arloth J, Pütz B, et al. Dexamethasone stimulated gene expression in peripheral blood is a sensitive marker for glucocorticoid receptor resistance in depressed patients[J]. Neuropsychopharmacology,2012,37(6):1455-1464.

[14] Guilloux JP,Bassi S,Ding Y,et al. Testing the predictive value of peripheral gene expression for nonremission following citalopram treatment for major depression[J]. Neuropsychopharmacology,2015,40(3):701-710.

[15] Jansen R,Penninx BW,Madar V,et al. Gene expression in major depressive disorder[J]. Mol Psychiatry,2016,21(3):339-347.

[16] Mostafavi S, Battle A, Zhu X, et al. Type I interferon signaling genes in recurrent major depression: increased expression detected by whole-blood RNA sequencing[J]. Mol Psychiatry,2014,19(12):1267-1274.

[17] Lin E, Tsai SJ. Genome-wide microarray analysis of gene expression profiling in major depression and antidepressant therapy[J]. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry,2016,64:334-340.

[18] Yi ZH,Li ZZ,Yu SY,et al. Blood-based gene expression profiles models for classification of subsyndromal symptomatic depression and major depressive disorder[J]. PLoS One,2012,7(2):e31283.

[19] Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments[J]. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol,2004,3:Article3.

[20] Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis[J]. BMC Bioinformatics,2008,9:559.

[21] Smith RS. The macrophage theory of depression[J]. Med Hypotheses,1991,35(4):298-306.

[22] Maes M. Evidence for an immune response in major depression: a review and hypothesis[J]. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 1995,19(1):11-38.

[23] Dantzer R, O′Connor JC, Freund GG, et al. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain[J]. Nat Rev Neurosci,2008,9(1):46-56.

[24] Felger JC. Imaging the role of inflammation in mood and anxiety-related disorders[J]. Curr Neuropharmacol,2018,16(5):533-558.

[25] Patel A. Review: the role of inflammation in depression[J]. Psychiatr Danub,2013,25(Suppl 2):S216-S223.

[26] Young JJ, Bruno D, Pomara N. A review of the relationship between proinflammatory cytokines and major depressive disorder[J]. J Affect Disord,2014,169:15-20.

[27] Noto C, Rizzo LB, Mansur RB, et al. Targeting the inflammatory pathway as a therapeutic tool for major depression[J]. Neuroimmunomodulation,2014,21(2/3):131-139.

[28] de Melo LGP, Nunes SOV, Anderson G, et al. Shared metabolic and immune-inflammatory, oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways in the metabolic syndrome and mood disorders[J]. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry,2017,78:34-50.

[29] Wang QZ,Roy B,Turecki G,et al. Role of complex epigenetic switching in tumor necrosis factor-α upregulation in the prefrontal cortex of suicide subjects[J]. Am J Psychiatry,2018,175(3):262-274.

[30] Miller AH, Raison CL. The role of inflammation in depression: from evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target[J]. Nat Rev Immunol,2016,16(1):22-34.

[31] Kappelmann N, Lewis G, Dantzer R, et al. Antidepressant activity of anticytokine treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials of chronic inflammatory conditions[J]. Mol Psychiatry, 2018, 23(2):335-343.

[32] Du W, Bautista JF, Yang HH, et al. Calcium-sensitive potassium channelopathy in human epilepsy and paroxysmal movement disorder[J].Nat Genet,2005,37(7):733-738.

[33] Baudewijns L, Ronsse E, Verstraete V, et al. Problem behaviours and major depressive disorder in adults with intellectual disability and autism[J].Psychiatry Res,2018,270:769-774.