戴尔有孢圆酵母调控晚采小芒森葡萄酒乙酸和香气

耿仕瑾,姜 娇,曲 睿,石 侃,秦 义,刘延琳,宋育阳

戴尔有孢圆酵母调控晚采小芒森葡萄酒乙酸和香气

耿仕瑾,姜 娇,曲 睿,石 侃,秦 义,刘延琳,宋育阳※

(西北农林科技大学葡萄酒学院,杨凌 712100)

为降低甜型葡萄酒中的挥发酸,进一步增加其香气复杂度,该研究利用本土戴尔有孢圆酵母R12与酿酒酵母NX11424同时接种和顺序接种发酵,研究其对贺兰山东麓产区晚采小芒森葡萄酒乙酸及香气成分的调控。与酿酒酵母单菌发酵相比,本土戴尔有孢圆酵母与酿酒酵母按照5:1、20:1、50:1的不同菌体数量比例同时接种和间隔5 d顺序接种发酵,均可以显著降低晚采小芒森葡萄酒的乙酸含量,其乙酸产率分别降低19.1%、21.2%、38.2%和48.9%。此外,按20:1比例同时接种发酵,可显著提高晚采小芒森葡萄酒中萜烯类和降异戊二烯类等品种香气物质含量,和乙酸异戊酯、丁酸乙酯及苯乙醇等发酵香气物质的含量。该研究表明合理的酿酒酵母接种发酵能有效降低高糖原料酿造葡萄酒挥发酸含量,为贺兰山东麓产区葡萄酒新产品的开发提供了的技术参考。

酵母;挥发酸;葡萄酒;同时接种发酵;顺序接种发酵;香气

0 引 言

用高糖葡萄,如冰葡萄、贵腐葡萄、晚采葡萄等酿造而成的葡萄酒常存在挥发酸偏高的问题,而乙酸是葡萄酒挥发酸的主要成分,是酵母代谢产物之一。干型葡萄酒中挥发酸的质量浓度在0.3~0.8 g/L之间,而高糖葡萄汁酿造的甜型葡萄酒、冰酒等挥发酸的质量浓度一般大于0.8 g/L[1]。高糖带来的过多的碳源和过高的渗透压,迫使酿酒酵母()在发酵过程代谢出更多的乙酸和其他不良代谢副产物[2]。裴广仁等研究结果表明,以作为发酵剂,当原料糖的质量浓度从230 g/L增加到450 g/L,发酵酒中的挥发酸含量可从0.25 g/L激增到1.60 g/L[3]。过高的乙酸含量会严重破坏葡萄酒品质,此外,GB 15037-2006葡萄酒[4]和GB/T 25504-2010冰葡萄酒[5]规定,葡萄酒(不含冰葡萄酒)和冰葡萄酒的挥发酸(以乙酸计,g/L)质量浓度分别不能超过1.2和2.4 g/L。因此,有效控制葡萄酒的乙酸含量具有重要的现实意义。

近年来,越来越多的研究表明部分非酿酒酵母(non-)在葡萄酒酿造过程中,具有低产乙醇、高产甘油、酯、甘露糖蛋白等特征[6],以及可以分泌更多胞外酶进而改善葡萄酒的香气、口感和色泽等品质的特点[7-10]。有研究表明,发酵菌株[2]、发酵温度[11]和葡萄原料含糖量[3]都会影响葡萄酒中乙酸含量,控制低温发酵难度较大,并且容易导致葡萄酒发酵停滞,而利用低产乙酸的酵母作为发酵剂是更为简单和经济的方式。戴尔有孢圆酵母(),具有较高的酒精发酵能力,是目前商业化程度最高的非酿酒酵母之一[12]。Bely等[13]利用与混合发酵高糖葡萄汁(含糖量360 g/L)可以显著降低高糖葡萄汁发酵葡萄酒中乙酸的含量。此外,发酵葡萄酒产生的某些物质对于葡萄酒的香气具有重要影响。有研究指出,与顺序接种发酵可以增加葡萄酒中丙酸乙酯、异丁酸乙酯和二氢肉桂酸乙酯等酯类香气物质含量,发酵结束后的酒样中果香馥郁[14];Sadoudi等[15]利用与混合发酵来探索其在长相思葡萄酒中的应用潜力,混合发酵可提高葡萄酒中C6化合物、萜烯类和苯乙醇的含量。

本研究以来源于贺兰山东麓具有自主知识产权的本土NX11424和来源于甘肃祁连的具有耐受高糖、低产挥发酸的R12[16]为发酵菌株,以贺兰山东麓产区的晚采小芒森()葡萄为原料酿造晚采小芒森甜白葡萄酒,探究NX11424和R12不同接种发酵方式(不同比例同时接种、顺序接种)对晚采小芒森甜白葡萄酒乙酸产量和香气的调控,以期获得基于本土酵母的可以有效降低晚采小芒森甜白葡萄酒挥发酸含量和增加其香气复杂度的发酵模式,为高糖葡萄原料葡萄酒的酿造和为贺兰山东麓产区葡萄酒新产品的开发提供技术支持。

1 材料与方法

1.1 葡萄原料及菌株

葡萄原料:2019年宁夏贺兰山东麓晚采小芒森葡萄,还原糖含量302.1 g/L,总酸含量4.9 g/L(以酒石酸计),可同化氮含量154.1 mg/L。

菌株:分离自甘肃祁连葡萄酒厂冰酒酒窖中的本土戴尔有孢圆酵母()R12;本土商业酿酒酵母()NX11424。

1.2 发酵条件

接种方式:1)单菌发酵:将在YPD中活化48 h的和分别接种发酵,接种量为1×106cells/mL,文中分别以“Td”和“Sc”表示。2)混合发酵:同时接种的总接种量为1×106cells/mL,接种比例设置与菌数比例分别为5:1、20:1和50:1,文中分别以“5:1”、“20:1”和“50:1”表示;顺序接种先接种1×106cells/mL的,间隔5 d后接种1×106cells/mL的,文中以“顺序接种”表示。

发酵试验:将晚采的新鲜小芒森葡萄,除梗破碎,压榨取汁,取汁过程中及时添加60 mg/L的SO2(以亚硫酸计)。将葡萄汁放置于4 ℃冷库进行低温澄清24 h,分离清汁后进行离心(8 000 r/min, 30 min),将离心后的上清葡萄汁进行0.22m滤膜过滤除菌,分装150 mL葡萄汁于250 mL已灭菌锥形瓶中。接种酵母启动发酵,发酵温度20 ℃,发酵过程中每48 h取一次样,发酵至20 d时添加60 mg/L的SO2(以亚硫酸计)停止发酵,将成品酒样保存在−20 ℃下备用。

1.3 酵母生长测定

采用平板菌落计数监测两种酵母在发酵过程中的菌落数量并绘制各处理的生长动力学曲线。发酵过程中每隔48 h测定一次酵母数(从接种0 h起至发酵结束)。用无菌水对发酵样品进行梯度稀释,并在WL固体培养基上涂板培养三天后根据颜色和形态不同进行菌落计数[17]。形成圆形绿色菌落,形成乳白色至浅绿色的乳头状菌落。

1.4 理化指标测定

部分理化指标使用Y15全自动分析仪(Biosystems, Barcelona, Spain)进行测定。使用Biosystems(http://www.biosystems.es)试剂盒对发酵过程中的还原糖和乙酸进行监测,对发酵结束后的可同化氮、总酸、甘油和乙醛进行测定。其余常规理化指标测定的具体研究和分析方法参考《葡萄酒分析检测》[18]进行。

1.5 香气成分测定

顶空固相微萃取:量取5.0 mL待测酒样置于15 mL样品瓶中,加入1.0 g NaCl、10L内标(4-甲基-2-戊醇,2 000 mg/L)和磁力搅拌转子,置于磁力搅拌台上40 ℃下搅拌30 min,随后插入萃取头,40 ℃下搅拌加热顶空萃取30 min,然后将萃取头插入GC进样口在250 ℃下热解析8 min。

GC-MS分析:气相色谱为Agilent 7890B GC,质谱为Agilent 5975B MS(Agilent, USA),配备HP-INNOWAX(60 m×0.25 mm×0.25m)色谱柱,不分流自动进样,载气为高纯氦气,流速1 mL/min。进样口温度250 ℃,质谱接口温度280 ℃,离子源温度230 ℃。升温程序为初始温度50 ℃保持1 min,然后以3 ℃/min升至220 ℃保持5 min。质谱电离方式EI,离子能量70 eV,全扫描质谱范围25~350 m/z。

定性定量分析:采用NIST14谱库查询及与NIST Chemical webbook保留指数(Retention Index, RI)对比定性化合物。采用标准曲线定量法对化合物进行定量,对没有标样的化合物采用内标法进行半定量,内标物为4-甲基-2-戊醇。

1.6 统计分析

采用Microsoft Excel 2017(Microsoft, USA)对试验数据进行基本统计分析,采用SPSS 18.0(SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA)进行ANOVA单因素分析(Duncan,<0.05)和主成分分析(Principal Component Analysis, PCA)。

2 结果与分析

2.1 发酵过程中酵母生长及对糖的利用

相比于单菌发酵(Sc)和同时接种,单菌发酵(Td)和顺序接种发酵速度相对较慢,在第14天发酵停滞。同时接种的葡萄汁前6 d发酵速率较慢,尤其是和按照50:1比例同时接种混合发酵,在启酵6 d之后还原糖消耗速度与Sc差异不明显(图1)。

所有接种方式中酵母都在接种后第1天迅速增长,第4~6天活菌数达到最大值,之后进入稳定期。由图1a和图1b可知,Sc和Td初期菌体增长速度基本相同,在发酵第4天进入稳定期,在第12天后进入迅速衰亡期,第18天已检测不到活菌,然而在18 d后仍有7.2 lg CFU/mL活菌存在。图1c、1d和1e分别显示混合发酵下不同接种比例同时接种和的菌株生长情况。随着发酵的进行,菌体量在第8天后都会呈现迅速下降的趋势,接种比例越低其菌体下降速率越快,菌体存活时间越短。和在5:1、20:1和50:1的接种比例下,酿酒酵母最大菌体数量分别在7.8、7.7和7.65lg CFU/mL。在间隔5 d顺序接种发酵中(图1a~图1f),在第4天达到最大值7.75 lg CFU/mL,但第5天接种的生长受到明显抑制,在发酵过程中菌体数量始终维持较低水平(约6.5 lg CFU/mL),显著小于Sc发酵的最大菌体数量。

注:Td、Sc、5:1、20:1、50:1和顺序接种分别表示单菌发酵、单菌发酵、与菌数比例5:1、20:1、50:1同时接种和与间隔5 d顺序接种。

Note: Td, Sc, 5:1, 20:1, 50:1 and sequential inoculation represent single fermentation with, single fermentationwith, co-inoculation ofandat the rate of 5:1, 20:1 and 50:1, and sequential inoculation withandat 5 d intervals, respectively.

图1 不同接种方式酒精发酵过程中酵母菌生长及发酵曲线

Fig.1 Viable cell numbers of yeasts and consumption of sugar during fermentation with different inoculation strategies

2.2 不同接种发酵模式对乙酸产量和产率的调控

混合发酵过程中的乙酸产量显著低于Sc(图2),同时接种酒样的乙酸含量对比Sc酒样显著降低17.6%~41.7%,减少0.2~0.5 g/L,并随接种比例的增加,乙酸含量降低得越显著。

从图2可以看出,在整个发酵过程中,Sc的乙酸产率显著高于其余接种方式,按5:1、20:1、50:1比例同时接种和间隔5 d顺序接种的酒样乙酸产率分别降低19.1%、21.2%、38.2%和48.9%。值得注意的是,Sc酒样在整个发酵过程中前4 d乙酸产率最高(4.7 mg/g 还原糖),5:1和20:1酒样也具有相同特征,而Td在发酵初期乙酸产率最低(2.3 mg/g 还原糖)。

2.3 不同接种模式下的葡萄酒主要理化指标

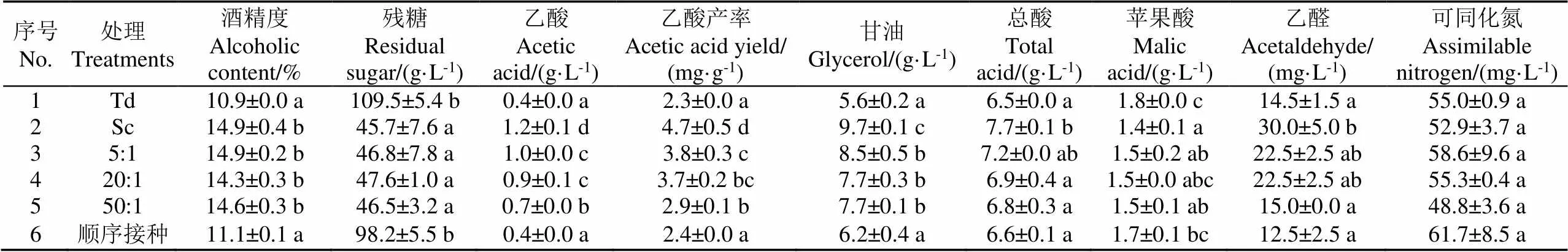

所有发酵在第20天时结束,对不同接种方式发酵结束后的甜白葡萄酒基本理化指标进行了检测(表1)。残糖质量浓度均高于45 g/L,Sc和同时接种酒样的残糖显著低于Td和顺序接种酒样。混合发酵成品酒样中乙酸和乙醛的含量显著低于Sc酒样,并且随着接种比例的增大降低更显著,其中50:1成品酒样的乙酸和乙醛含量仅为Sc成品酒样含量的41.7%和50.0%。

2.4 不同接种模式对葡萄酒香气的调控

通过对不同接种方式发酵的成品酒样进行香气成分定性定量分析,共鉴定出42种挥发性香气物质(表2),包括10种品种香气和32种发酵香气。

由表2可以看出,随着接种比例的增加,C6化合物的总含量也随之增加,其中1-己醇的含量在不同处理的酒样中具有显著性差异,混合发酵酒样的1-己醇含量是Sc成品酒样的2倍左右。顺序发酵酒样中萜烯类和C13-降异戊二烯类香气含量最高,相比Sc酒样,混合发酵显著增加了柠檬烯、里那醇、香叶醇和-紫罗兰酮,为葡萄酒带来果香和花香等良好品种香气。供试酒样中共检出3种苯乙基类化合物,其中只有苯乙醇的OAV>1。苯乙醇赋予葡萄酒玫瑰花香,在供试酒样中的含量为42.1~82.6 mg/L,苯乙醇在混合发酵酒样中的含量显著高于Sc,且相比Sc顺序接种增加了96.2%。

表1 不同接种方式发酵的成品酒样中主要理化指标

注:表中同一列中不同字母表示处理间具有显著性差异(Duncan检验,<0.05)。

Note: Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences between treatments (Duncan's test,<0.05).

表2 不同接种方式‘小芒森’酒样中挥发性香气物质

注:RI为该物质在HP-innowax毛细管柱上的保留指数;表中同一行中不同字母表示处理间具有显著性差异(Duncan检验,<0.05)。

Note: RI is the retention index of the substance on the HP-innowax capillary column; Different letters in the same roe indicate significant differences between treatments (Duncan’s test,<0.05).

对于高级醇,与Sc酒样相比,Td中的高级醇含量下降了大约30 mg/L,混合发酵酒样中高级醇含量也不同程度的下降。酯类物质的含量在葡萄酒中仅次于高级醇,其对葡萄酒的感官品质有重要影响,通过表2可以看出不同接种方式成品酒样的酯类物质含量差异较大。相比于Sc,同时接种酒样中一些酯类物质,如乙酸异丁酯、乙酸异戊酯、乙酸己酯和丁酸乙酯显著增加,其中乙酸异戊酯和丁酸乙酯OVA值大于1,而乙酸苯乙酯、辛酸乙酯、癸酸乙酯和月桂酸乙酯则显著降低。同时接种5:1成品酒样的脂肪酸含量在所有供试酒样中最高,同时接种中随着接种比例的增加,脂肪酸含量减少。供试酒样共检出4种羰基化合物,分别为壬醛、癸醛、糠醛和乙偶姻,含量均较低,混合发酵可以显著降低甜白葡萄酒中乙偶姻的含量,其中同时接种50:1成品酒样中乙偶姻含量最低,相比Sc降低了47.2%。

为了分析品种香气和发酵香气在不同酒样间的差异,本试验对OAV>0.1的香气成分进行主成分分析,前两个主成分分别占了总方差的59.56%和16.66%,两个方差累计贡献76.22%,香气成分和供试酒样在前两个主成分上的载荷见图3。该图反映出不同接种方式发酵的成品酒样间香气的差异,其中Td和顺序接种处理聚集在品种香气周围,而5:1、20:1和50:1则聚集在发酵香气周围,Sc周围没有香气分布。值得注意的是,品种香气和发酵香气均环绕在同时接种20:1处理附近,说明同时接种20:1的接种方式可同时显著提高小芒森甜白葡萄酒中品种香气和发酵香气的物质含量。

3 讨 论

本研究采用与按照5:1、20:1、50:1同时接种和顺序接种方式进行混合发酵,均能有效调控晚采小芒森葡萄酒中乙酸的含量,乙酸产率分别降低19.1%、21.2%、38.2%和48.9%(表1)。与本研究类似,Azzolini等[27]也发现利用与混合发酵Vino Santo甜型葡萄酒乙酸含量显著降低,乙酸含量降低了0.29~0.37 g/L。Bely等[13]使用和以不同接种方式在赛美容贵腐酒中进行混合发酵,其中同时接种比例为20:1时乙酸降低最显著降低了53%。Tondini等[28]认为缺失(ALD3),并且的乙醇脱氢酶(ADH1~7)表达量高于(ALD2~6),是能够显著降低葡萄酒中乙酸含量的主要原因。

值得关注的是,接种能够显著降低发酵初期乙酸产率(图2),该特征十分有利于混合发酵在生产中的应用,因为在发酵中后期,随着的快速增殖和酒种乙醇含量的增加,非酿酒酵母的生长会受到显著抑制(图1)。Tondini等[29]认为在发酵初期显著降低乙酸产率是其高渗胁迫适应性反应的结果,而在接种到高糖环境初期,乙醛脱氢酶(ALD3和ALD6)等基因的应激瞬时高表达导致短时间内乙酸产量显著增加[30-32]。

除了挥发酸的显著降低外,和混合发酵也显著提高了晚采小芒森葡萄酒中一类香气物质萜烯类和-紫罗兰酮的含量,和二类香气物质乙酸异戊酯、丁酸乙酯及苯乙醇的含量。来源于葡萄品种的香气成分为葡萄酒提供典型香气特征,非酿酒酵母在发酵过程中可以分泌大量胞外酶,通过水解糖苷结合态香气物质释放游离态品种香气成分[33]。Cus等[34]使用混合发酵芳香葡萄品种‘琼瑶浆’会释放出更多的萜烯类香气物质,尤其是-萜品醇和里那醇,提高了葡萄酒整体品质。本研究发现,与混合发酵小芒森葡萄汁,会显著增加葡萄酒中的品种香气,尤其是萜烯类化合物(柠檬烯、里那醇、香叶醇)和C13-去甲类异戊二烯(-紫罗兰酮),并且随着接种比例的增加而增强(表2),这可能与分泌更多的胞外酶以及单萜类化合物生物转化能力较强[35]有关。此外,混合发酵可以显著提高苯乙醇的含量,这可能是酵母中-葡萄糖苷酶与-苯丙氨酸的代谢共同作用的结果[36]。葡萄酒中的酯类物质在甜酒中具有很高的香气活性[37],赋予葡萄酒‘果香’的特性[38]。Renault等[14]报道了顺序接种可以显著提高酯类香气,其中乙酸异丁酯和乙酸异戊酯的浓度分别增加约50g/L和2 mg/L,Belda等[39]也报道了在顺序接种中乙酸异戊酯显著增加1 mg/L。本研究中,同时接种中乙酸异丁酯、乙酸异戊酯、乙酸己酯和丁酸乙酯显著增加,其中乙酸异戊酯和丁酸乙酯OVA值大于1,分别增加约60和70g/L,为葡萄酒提供更浓郁的‘香蕉’香气。乙偶姻是酒精发酵的副产物,含量过高会使葡萄酒出现酸败的味道,并且在甜型葡萄酒中含量相对较高[40],虽然在本研究中乙偶姻的OVA值小于1,但混菌发酵可以显著降低甜白葡萄酒中乙偶姻的含量,这与之前文献报道相同[41]。

4 结 论

本研究利用优选本土R12与源于贺兰山东麓的本土NX11424,以不同比例同时接种和间隔5 d顺序接种,酿造晚采‘小芒森’葡萄酒,发现接种本土可以显著降低晚采‘小芒森’葡萄酒的乙酸含量,还能够显著降低乙醛和乙偶姻等不良产物含量。同时接种弥补了发酵能力较弱的缺点,且当接种比例为20:1时,能够最大限度地发挥的产香特性,既显著提高晚采‘小芒森’葡萄酒中萜烯类(柠檬烯、里那醇、香叶醇等)和降异戊二烯(-紫罗兰酮)等品种香气物质含量,又增强了乙酸异戊酯、丁酸乙酯及苯乙醇等发酵香气物质的含量。因此,本研究认为R12具有有效降低高糖原料酿造葡萄酒挥发酸含量及增香酿造葡萄酒的应用潜力,研究结果为贺兰山东麓产区葡萄酒新产品的开发提供了全新的技术方案。

[1] Chidi B S, Bauer F F, Rossouw D. Organic acid metabolism and the impact of fermentation practices on wine acidity: A review[J]. South African Journal of Enology and Viticulture, 2018, 39(2): 315-329.

[2] Kontkanen D, Inglis D L, Pickering G J, et al. Effect of yeast inoculation rate, acclimatization, and nutrient addition on ice wine fermentation[J]. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture, 2004, 55(4): 363-370.

[3] 裴广仁,李记明,于英,等. 冰葡萄酒中高含量挥发酸的影响因素分析[J]. 食品与发酵工业,2014,40(3):58-62.

Pei Guangren, Li Jiming, Yu Ying, et al. Influencing factors of high content volatile acid in icewine[J]. Food and Fermentation Industries, 2014, 40(3): 58-62. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[4] 中华人民共和国国家质量监督检验检疫总局和中国国家标准化管理委员会. 葡萄酒: GB/T 15037-2006[S]. 北京:中国标准出版社,2006.

[5] 中华人民共和国国家质量监督检验检疫总局和中国国家标准化管理委员会. 冰葡萄酒: GB/T 25504-2010[S]. 北京:中国标准出版社,2010.

[6] 战吉宬,曹梦竹,游义琳,等. 非酿酒酵母在葡萄酒酿造中的应用[J].中国农业科学,2020,53(19):4055-4069.

Zhan Jicheng, Cao Mengzhu, You Yilin, et al. Research advance on the application of non-in winemaking[J]. Scientia Agricultura Sinica, 2020, 53(19): 4055-4069. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[7] 覃秋杏,韩小雨,黄卫东,等. 非酿酒酵母产生的-葡萄糖苷酶在发酵酒中的应用[J/OL]. (2020-12-04) [2021-01-21].http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.2206.TS.20201211.1614.008.html.

Qin Qiuxing, Han Xiaoyu, Huang Weidong, et al. Application of-glucosidase produced by non-in fermented wine[J/OL]. (2020-12-04) [2021-01-21]. http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.2206.TS.20201211.1614.008.html. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[8] Rainieri S, Pretorius I S. Selection and improvement of wine yeasts[J]. Annals of Microbiology, 2000, 50(1): 15-31.

[9] Lee P R, Kho S H C, Yu B, et al. Yeast ratio is a critical factor for sequential fermentation of papaya wine byand[J]. Microbial Biotechnology, 2013, 6(4): 385-393.

[10] Erasmus D J, Cliff M, Vuuren H J J V. Impact of yeast strain on the production of acetic acid, glycerol, and the sensory attributes of icewine[J]. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture, 2004, 55(12): 883-883.

[11] Beltran G, Novo M, José M G, et al. Effect of fermentation temperature and culture media on the yeast lipid composition and wine volatile compounds[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2008, 121(2): 169-177.

[12] Varela C, Borneman A R. Yeasts found in vineyards and wineries[J]. Yeast, 2016, 34(3): 111-128.

[13] Bely M, Stoeckle P, Isabelle M, et al. Impact of mixed-culture on high-sugar fermentation[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2008, 122(3): 312-320.

[14] Renault P, Coulon J, de Revel G, et al. Increase of fruity aroma during mixed/wine fermentation is linked to specific esters enhancement[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2015, 207: 40-48.

[15] Sadoudi M, Tourdot-Marechal R, Rousseaux S, et al. Yeast-yeast interactions revealed by aromatic profile analysis of Sauvignon Blanc wine fermented by single or co-culture of nonandyeasts[J]. Food Microbiology, 2012, 32(2): 243-253.

[16] 杨诗妮,叶冬青,贾红帅,等. 本土戴尔有孢圆酵母在葡萄酒酿造中的应用潜力[J]. 食品科学,2019,40(18):108-115.

Yang Shini, Ye Dongqing, Jia Hongshuai, et al. Oenological potential of indigenousfor winemaking[J]. Food Science, 2019, 40(18): 108-115. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[17] Pallmann C L, Brown J A, Olineka T L, et al. Use of WL medium to profile native flora fermentations[J]. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture, 2016, 52(3): 198-203.

[18] 王华. 葡萄酒分析检验[M]. 北京:中国农业出版社,2010.

[19] Guth H. Quantitation and sensory studies of character impact odorants of different white wine varieties[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 1997, 45(8): 3027-3032.

[20] Crandles M, Reynolds A G, Khairallah R, et al. The effect of yeast strain on odor active compounds in Riesling and Vidal blanc icewines[J]. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 2015, 64(1): 243-258.

[21] Coelho E, Coimbra M A, Nogueira J M F, et al. Quantification approach for assessment of sparkling wine volatiles from different soils, ripening stages, and varieties by stir bar sorptive extraction with liquid desorption[J]. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2009, 635(2): 214-221.

[22] Tao Y S, Liu Y Q, Li H. Sensory characters of Cabernet Sauvignon dry red wine from Changli County (China)[J]. Food Chemistry, 2009, 114(2): 565-569.

[23] Ferreira V, López R, Cacho J F. Quantitative determination of the odorants of young red wines from different grape varieties[J]. Journal of Science of Food Agriculture, 2000, 80(11): 1659-1667.

[24] Mayr C M, Geue J P, Holt H E, et al. Characterization of the key aroma compounds in Shiraz wine by quantitation, aroma reconstitution, and omission studies[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2014, 62(20): 4528-4536.

[25] Laura F, Valeria V, Gaston A, et al. Volatile composition and aroma profile of Uruguayan Tannat wines[J]. Food Research International, 2015, 69: 244-255.

[26] Lerma N L D, Bellincontro A, Mencarelli F, et al. Use of electronic nose, validated by GC-MS, to establish the optimum off-vine dehydration time of wine grapes[J]. Food Chemistry, 2012, 130(2): 447-452.

[27] Azzolini M, Tosi E, Lorenzini M, et al. Contribution to the aroma of white wines by controlledcultures in association with[J]. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2015, 31(2): 277-293.

[28] Tondini F, Lang T, Chen L, et al. Linking gene expression and oenological traits: Comparison betweenandstrains[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2019, 294: 42-49.

[29] Tondini F, Onetto C A, Jiranek V. Early adaptation strategies ofandto co-inoculation in high sugar grape must-like media[J]. Food Microbiology, 2020, 90: 1-9.

[30] Heit C, Martin S J, Yang F, et al. Osmoadaptation of wine yeast () during icewine fermentation leads to high levels of acetic acid[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2018, 124(6): 1506-1520.

[31] Noti O, Vaudano E, Pessione E, et al. Short-term response of differentstrains to hyperosmotic stress caused by inoculation in grape must: RT-qPCR study and metabolite analysis[J]. Food Microbiology, 2015, 52: 49-58.

[32] Zuzuarregui A, Delolmo M. Expression of stress response genes in wine strains with different fermentative behavior[J]. Fems Yeast Research, 2004, 4(7): 699-710.

[33] Azzolini M, Fedrizzi B, Tosi E, et al. Effects ofandmixed cultures on fermentation and aroma of Amarone wine[J]. European Food Research and Technology, 2012, 235(2): 303-313.

[34] Cus F, Jenko M. The influence of yeast strains on the composition and sensory quality of Gewürztraminer wine[J]. Food Technology and Biotechnology, 2013, 51(4): 547-553.

[35] King A. Biotransformation of monoterpene alcohols by,and[J]. Yeast, 2010, 16(6): 499-506.

[36] 原苗苗,姜凯凯,孙玉霞,等. 戴尔有孢圆酵母对葡萄酒香气的影响[J]. 食品科学,2018,39(4): 99-105.

Yuan Miaomiao, Jiang Kaikai, Sun Yuxia, et al. Effects ofon wine aroma[J]. Food Science, 2018, 39(4): 99-105. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[37] Plata C, Millan C, Mauricio J C, et al. Formation of ethyl acetate and isoamyl acetate by various species of wine yeasts[J]. Food Microbiology, 2003, 20(2): 217-224.

[38] Hu K, Jin G J, Mei W C, et al. Increase of medium-chain fatty acid ethyl ester content in mixed/Sfermentation leads to wine fruity aroma enhancement[J]. Food Chemistry, 2018, 239(15): 495-501.

[39] Belda I, Ruiz J, Beisert B, et al. Influence ofin varietal thiol (3-SH and 4-MSP) release in wine sequential fermentations[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2017, 257: 183-191.

[40] 陈乃用. 葡萄酒酿酒酵母产生的乙偶姻[J]. 工业微生物,1994(1):44-45.

[41] Escribano R, González-Arenzana L,Portu J. et al. Wine aromatic compound production and fermentative behaviour within different non-species and clones[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2018, 124(6): 1521-1531.

Managing volatile acidity and aroma of Petit Manseng wine using

Geng Shijin, Jiang Jiao, Qu Rui, Shi Kan, Qin Yi, Liu Yanlin, Song Yuyang※

(,,712100,)

Volatile acids are usually associated with undesirable “sour” and “bitter” descriptors. The fermentation of high sugar grape juice/must using chilled, botrytised or late harvested grapes often leads to the production of higher amounts of volatile acidity, which adversely impacts the overall wine quality. This work aims to minimize the formation of volatile acidity, and further improve aroma complexity during high sugar fermentation. The potential application of indigenousR12 was evaluated using late harvested Petit Manseng from east foot hill of the Helan Mountain.Petit Manseng juice with 300 g/L of sugar was filter sterilized prior to inoculation. Three inoculation strategies were used: 1) single fermentation with either pure R12 or indigenousNX11424 at 1×106cells/mL; 2) co-inoculation of R12 and NX11424 at the rate of 5:1, 20:1, and 50:1, among which the inoculum of R12 was 1×106cells/mL; 3) 1×106cells/mL of R12 was inoculated prior to the inoculation of NX11424 after 5 d at the same rate. Fermentation samples were collected every 48 h to measure the residual sugar and the formation of acetic acid using enzymatic analysis. Yeast viability was also determined via serial dilution and plating on WLN agar medium. Fermentation was terminated with the addition of 60 mg/L SO2on the day of the 20th. Final ferments were centrifuged and stored for subsequent analysis on volatile compounds via head-space-solid phase micro extraction–gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (HS-SPME-GC-MS). NX11424 monoculture fermentation was rapid, when utilizing 255 g/L of sugar in 20 d, whereas, the sugar consumption of R12 fermentations was relatively slower, almost halted at 20 d. Nevertheless, the fermentation power was much stronger in all the co-inoculated fermentations than that in both the R12 monoculture fermentations and the sequentially inoculated fermentations. Correspondingly, the viability of both yeast strains in each fermentation was inversely related to sugar consumption. In terms of acetic acid(the major component responsible for volatile acidity), NX11424 monoculture fermentation produced 1.2 g/L acetic acids, which fell just around the legal threshold. By contrast, there was a significant decrease in the amount of acetic acid for both co-inoculation with R12 at the ratio of 5:1, 20:1, and 50:1, and sequential inoculation. The reduction of acetic acid was in line with the increased proportion of R12 in the mixed inoculum, with the highest decrease being 48.9% at 50:1 co-fermentation, compared with the single fermentation with NX11424. Another noticeable effect was that significantly less abundant acetaldehyde related to oxidative descriptors appeared in wines produced with the combined R12 and NX11424. The reduction of this compound was up to 50% in the mixed culture fermentation, compared with the NX11424 monoculture fermentation. Further, the impact of R12 on aroma profiles of wine was evaluated, where 42 volatile compounds were detected by HS-SPME-GC-MS in Petit Manseng wines. It was found that the application of R12 was significantly correlated with the decrease of higher alcohols up to 30 mg/L, compared with thecontrol. Significant differences were also observed in the concentration of esters. Specifically, the presence of R12 increased the level of isobutyl aetate, isoamyl acetate, hexyl acetate, and hexyl butyrate, whereas, remarkably reduced the production of phenethyl acetate, ethyl octanoate, ethyl decanoate, and ethyl dodecanoate. Lower concentrations of acetoin were also found in the wine samples involving R12. Additionally, a principal component analysis was utilized to clearly separate volatile compounds, where R12 inoculation strategies displayed a distinctive impact on wine aroma profile. In particular, the co-inoculation at the ratio of 20:1 behaved with the greatest potential to enhance both the varietal and the fermentative aromas of the wine. In this scenario, the amount of varietal volatile compounds was remarkably improved, such as terpenes, and C13 demethyl isoprene, whereas, a noticeable increase was also observed in the typical volatile compounds (eg., isoamyl acetate, ethyl butanoate, and phenyl ethanol)derived from fermentation. Therefore, the indigenousR12 was expected to serve in conjunction with, thereby reducing acetic acid for better aroma quality during fermentation with high sugar in grape juice/must. The findings expand current knowledge on the solutions to efficiently minimizing volatile acidity during high sugar fermentations.

yeast; volatile acid; wine; simultaneous inoculation fermentation; sequential inoculation fermentation; aroma

2020-01-21

2021-03-10

国家重点研发计划资助项目(2019YFD1002500);国家现代农业(葡萄)产业技术体系建设专项(CARS-29-jg-03);宁夏回族自治区重大研发计划项目(2020BCF01003);西北农林科技大学试验示范站(基地)科技成果推广项目(TGZX2019-27)

耿仕瑾,研究方向为葡萄酒微生物。Email:gengshijinj@163.com

宋育阳,博士,副教授,研究方向为酿酒微生物。Email:yuyangsong@nwsuaf.edu.cn

10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2021.07.036

TS262.6

A

1002-6819(2021)-07-0293-08

耿仕瑾,姜娇,曲睿,等. 戴尔有孢圆酵母调控晚采小芒森葡萄酒乙酸和香气[J]. 农业工程学报,2021,37(7):293-300. doi:10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2021.07.036 http://www.tcsae.org

Geng Shijin, Jiang Jiao, Qu Rui, et al.Managing volatile acidity and aroma of Petit Manseng wine using[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering (Transactions of the CSAE), 2021, 37(7): 293-300. (in Chinese with English abstract) doi:10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2021.07.036 http://www.tcsae.org