Sensor-based physical activity,sedentary time,and reported cell phone screen time:A hierarchy of correlates in youthT

Pedro B.Jdice*,Joo P.Mglhes,Gil B.Ros,Durte Henriques-Neto,Megn Hetherington-Ruth,Lus B.SrdinhT

aExercise and Health Laboratory,CIPER,Faculty of Human Kinetics,University of Lisbon,Lisbon 1499-002,Portugal

bFaculty of Physical Education and Sport,Lusofona University,Lisbon 1749-024,Portugal T

Received 15 October 2019;revised 13 December 2019;accepted 16 January 2020 Available online 16 March 2020

2095-2546/©2021 Published by Elsevier B.V.on behalf of Shanghai University of Sport.This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license.(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

Abstract Background:Evidence on correlates relies on subjective metrics and fails to include correlates across all levels of the ecologic model.We determined which correlates best predict sensor-based physical activity(PA),sedentary time(ST),and self-reported cell phone screen time(CST)in a large sample of youth,while considering a multiplicity of correlates.Methods:Using sensor-based accelerometry,we assessed the PA and ST of 2179 youths.A x2automatic interaction detection algorithm was used to hierarchize the correlates associated with too much ST(>50th percentile),insuf ficient moderate-to-vigorous PA(MVPA)(<60 min/day),and prolonged CST(≥2 h/day).Results:Among youth 10-14 years old,the correlates for being inactive consisted of being a girl,not having sport facilities in the neighborhood,and not perceiving the neighborhood as a safe place,whereas in the youth 15-18 years old,the correlate for being inactive was not performing sports(9.7%chance of being active).The correlates for predicting high ST in the younger group was not performing sports(55.8%chance for high ST),and in the older group,the correlates were not owning a pet,perceiving the neighborhood as safe,and having inactive parents(63.7%chance for high ST).In the younger group,the greatest chances of having high CST were among those who were in the last elementary school years,who were girls,and who did not have friends in the neighborhood(73.1%chance for high CST),whereas in the older group,the greatest chance for having high CST was among those who were girls and had a TV in the bedroom(74.3%chance for high CST).Conclusion:To counteract ST and boost MVPA among youths,a speci fic focus on girls,the promotion of sport participation and facilities,neighborhood safety,and involvement of family must be prioritized.

Keywords:Adolescents;Environment;Objective;Sedentary behavior;Socioecologic model

1.Introduction

Global physical inactivity is responsible for more than 5 million deaths,1and cross-sectional evidence has found both low physical activity(PA)and high sedentary time(ST)to be important risk factors for chronic disease in youth,2although the associations for ST with health parameters seem to be fairly dependent on PA levels.3Indeed,PA levels can predict the future health of youth.4Hence,understanding which modif i able and nonmodi fiable factors(i.e.,correlates)can impact PA levels in this population is paramount.5There are correlates that seem to affect the PA of youth,5-8but current f i ndings are less consistent than those in adults,9,10which can be justi fied by the lower number of investigations using sensor-based PA data in youth.

Even though there is evidence suggesting that PA is a better predictor of health in youth than ST,3the great percentage of time spent in sedentary behavior(SB)11justi fies a closer look into the correlates that can impact this potential deleterious behavior.Considering that SB is a distinct concept separate from physical inactivity,12it is plausible that correlates may be speci fic for this behavior.For example,a meta-analysis13found that interaction with friends and colleagues had no impact on ST,but with regard to PA,social support was associated with more PA.14,15In youth,there are different levels of factors that can in fluence ST,such as sociodemographic correlates(e.g.,gender and household income),16environmental correlates(e.g.,neighborhood connectivity and safety),17and household correlates,such as the existence and number of screens at home.18The socioecologic model of health behavior recognizes that particular behaviors such as SB operate in,and are in fluenced by,environmental and policy contexts.19This model places the individual at the center of an ecosystem and provides a better understanding of the several factors and barriers that impact a particular behavior.19Thus,using the socioecologic model to examine and hierarchize different levels of correlates as a hypothesis-generating framework is paramount.20

When looking at correlates,it is also important to go deeper into the type of behavior that is being analyzed.For instance,more education has been related with more computer time21and less TV viewing time.22In youth,interactions between correlates for a given outcome may also exist.23For example,a higher income is associated with less ST,16but a higher income can potentiate the presence of a TV in the bedroom which,in turn,can potentially increase ST.18Thus,it is important to consider simultaneously the relative importance of different types of correlates and hierarchize them.Most evidence on the correlates of PA and ST in youth have relied on subjective metrics for ST and PA,7,24,25which may induce an assessment bias.26Among the studies using sensor-based data,often only a unique type of correlate is considered27(e.g.,environmental correlates).Therefore,when looking at the correlates of PA and ST in youth,investigations that use sensor-based data6,17,28,29and that identify correlates across all levels of the socioecologic model30are warranted.

Recently,there has been a growing concern with cell phone screen time(CST)in youth,with young individuals spending progressively more time in this sedentary pursuit.31However,most investigations have focused on overall screen time8,23,31and have failed to consider a wider spectrum of correlates.32It is likely that the correlates for PA,ST,and CST differ,33but previous investigations have not simultaneously considered these independent behaviors using a large sample of youth varying in age.Thus,this is the first investigation to use the socioecologic model in a large sample of youth to determine and hierarchize the correlates that best predict sensor-based PA,ST,and self-reported CST while simultaneously considering intrapersonal,interpersonal,and neighborhood-physical environmental factors.

2.Materials and methods

2.1.Participants and study design

This investigation included a total of 2179 youths living in Portugal(i.e.,97.4%were Portuguese)from a subsample of a nationwide cross-sectional survey that aimed to examine PA levels using sensor-based data.In the Portuguese school system,the architecture and contextual settings of the elementary school(where students are 10-14 years old)and high school(where students are 15-18 years old)substantially change.Thus,analyses were performed separately for these 2 age groups.Data were collected during physical education classes in public schools between March 2017 and November 2018.All participants were informed about the project’s protocol,and written consent was obtained from the students’legal guardians prior to their participation.The participants who did not comply with accelerometer criteria(i.e.,3 valid days with at least 1 weekend day)and/or did not answer one of the questions on the questionnaire were excluded,which left a total sample of 2179 participants.The investigation protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Human Kinetics,University of Lisbon(CEFMH-Approved;#19/2017).

2.2.Body composition

All participants were weighed to the nearest 0.01 kg on an electronic scale(Model 799;Seca GmbH,Hamburg,Germany)while wearing minimal clothing and without shoes.Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm with a portable stadiometer(Model 220;Seca GmbH).34All measurements were performed twice,and the mean of the 2 measurements was recorded.Body mass index was calculated as body mass/height2(kg/m2).

2.3.Accelerometer analysis

Total moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA)and ST were assessed by a sensor-based approach using accelerometry(GT3X model;ActiGraph,Fort Walton Beach,FL,USA).Participants were instructed to wear the device for 7 consecutive days,on the right side near the iliac crest,and were informed to remove the accelerometers during sleep and all water-based activities.The accelerometers were initialized to start recording at 8 a.m.on the evaluation day of each participant.The devices were activated on raw mode with a 100-Hz frequency and posteriorly downloaded into 15-s epochs(ActiLife Version 6.9.1;ActiGraph).Periods of at least 60 consecutive minutes of 0 count were considered as nonwear time.A valid day was considered when wear time was≥10 h.To be included in the analysis,the participants had to present at least 3 valid days(with at least 1 weekend day).Activity intensity thresholds were de fined according to Evenson et al.35Accelerometer counts≥100 counts/min were identi fied as active time,and MVPA(≥2296 counts/min).The time spent<100 counts/min was identi fied as ST.35

2.4.Sociodemographic,behavioral,and health-related characteristics

Data on the following participant characteristics were collected:sociodemographic variables(e.g.,age,gender,school year,parents’ages and education levels,living with 1 or both parents,having siblings or being the only child,and having lots of friends to play with),health status(e.g.,presence of disease,smoking habit,and perception of quality of health/life/sleep),behavioral status(e.g.,sport participation,type of activity most performed during recess at school,SB patterns,parents’performing exercise or not,friends’exercising or not,and owning a pet to walk),and contextual variables(e.g.,characteristics of neighborhood,such as safety,proximity of sports facilities,existence of violence,traf fic levels,cycling paths,not having a green park in the neighborhood,opportunities to play outdoors,having a TV in the bedroom,number of TVs and computers in the house,and parents owning a car).

Sociodemographic variables were collected,and gender was dichotomized as girl or boy.The current school year was coded as the corresponding number(e.g.,the 4th grade as 4).The education levels of mother and father were assessed separately and recoded as having no education(1),primary school(2),middle school(3),middle school(professional courses)(4),high school(5),or university graduation(6).

Household characteristics(living with both parents or not,living with siblings or being the only child)were determined according to an adapted question(“Who do you live with?”)from the Health Behavior in School-aged Children(HBSC)questionnaire36and then recoded as living with 1 parent or any other family member(0)or living with both parents(1).Furthermore,being the only child was categorized as 0,while living with at least 1 sibling was categorized as 1.Perception of quality of health was assessed by the question“How do you characterize your health?”adapted from the self-report of the Portuguese KIDSCREEN-10 questionnaire,which was recoded in a 5-point Likert scale as follows:poor(1),fair(2),good(3),very good(4),orexcellent(5).37Using the same scale,perceptions related to quality of life and quality of sleep were also assessed.Smoking habit was determined using an adapted question from the HBSC questionnaire(“Do you currently smoke?”),36and the answer was dichotomized as no or yes.A question about the existence of any diagnosed disease was asked,and the answer was coded as no or yes.

Sport participation was assessed based on the question“Do you perform any regular and structured sport during your leisure time?”and the answer was recoded as no or yes.The type of activity most performed during recess was assessed by the question “What is the activity that you do most during recess?”and the answer was recoded for one of 4 speci fic activities:sitting while talking with colleagues(1),standing while talking with colleagues(2),exercising or playing games with colleagues(3),and other activities(4).In addition,the manner in which ST was accumulated throughout the day was determined using the question“During the day,do you usually sit for a long period of time or do you break this behavior often?”and the answer was recoded for one of 3 speci fic items:several hours without breaking sitting time(1),breaking-up sitting every hour(2),or breaking-up sitting more often(3).

2.5.Contextual characteristics of neighborhood and social environment

We assessed the basic characteristics of neighborhood through 8 items:“Is it safe to walk in the street anytime?”;“Is there easy access to sports infrastructures?”;“Do you have outdoor places where you can play?”;“Is there a lot of traf fic?”;“Do you have many friends living close that you can play with?”;“Is there any risk of being beaten or robbed?”;“Are there suitable paths for cycling?”;and “Are there no green areas?”.For all these questions,a 2-point Likert scale(agree or disagree)was used.36Adapted questions from the HBSC questionnaire were also used to determine the number of home TVs(“How many TVs do you have at home?”)and computers(“How many computers do you have at home?”).36Several social-environment variables were assessed across 5 domains(“Do you have a TV in your bedroom?”;“Do your friends usually exercise?”;“Do your parents usually exercise?”;“Do you walk your pet in the street?”;and “Do your parents own a car?”),which were further recoded into 2 categories(no or yes).36All questions were asked in face-to-face interviews in which well-trained interviewers were instructed to use the same vocabulary and terminology.

2.6.Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were completed using SPSS(Version 24.0;IBM Corp.,Armonk,NY,USA).Descriptive analysis included mean and SD for all variables.To identify and hierarchize the correlates associated with too much ST,insuf ficient MVPA,and prolonged CST,an independent x2automatic interaction detection(CHAID)algorithm with a growing method was performed for each outcome.38The CHAID analysis generates a tree that hierarchically splits the data on the basis of the exposures into homogeneous subgroups.This allows for the identi fication of population subdivisions that have a higher likelihood of presenting an outcome(e.g.,ful filling MVPA recommendations).The resulting tree supports direct interpretation of complex interactions and is based on Bonferroni type-I error to discriminate the correlate and subdivide the data according to its categories.38In order to apply the CHAID algorithm,participants were dichotomized into low or high ST based on having low(<50 percentile)or high(≥50 percentile)amount of sensor-based ST,with the percentiles for ST being obtained afteradjustmentforgenderandage.ForMVPA,the current guidelines for youth were considered in order to differentiate between inactive(MVPA<60 min/day)and active(MVPA≥60 min/day)participants.For self-reported CST,we used the cut-off of 2 h/day to distinguish between low(<2 h/day)and high(≥2 h/day)CST,which parallels the new Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth,which states that youth should limit their screen time to a maximum of 2 h/day.39The time spent looking at the cell phone is the most prevalent type of screen time in youth,31which explains why we chose this domain solely.Because gender was included in the models as one of the 31 correlates,the analyses were not strati fied by gender.However,we separated the analyses based on 2 age groups:10-14 years old and 15-18 years old).Statistical significance was set at 5%.

3.Results

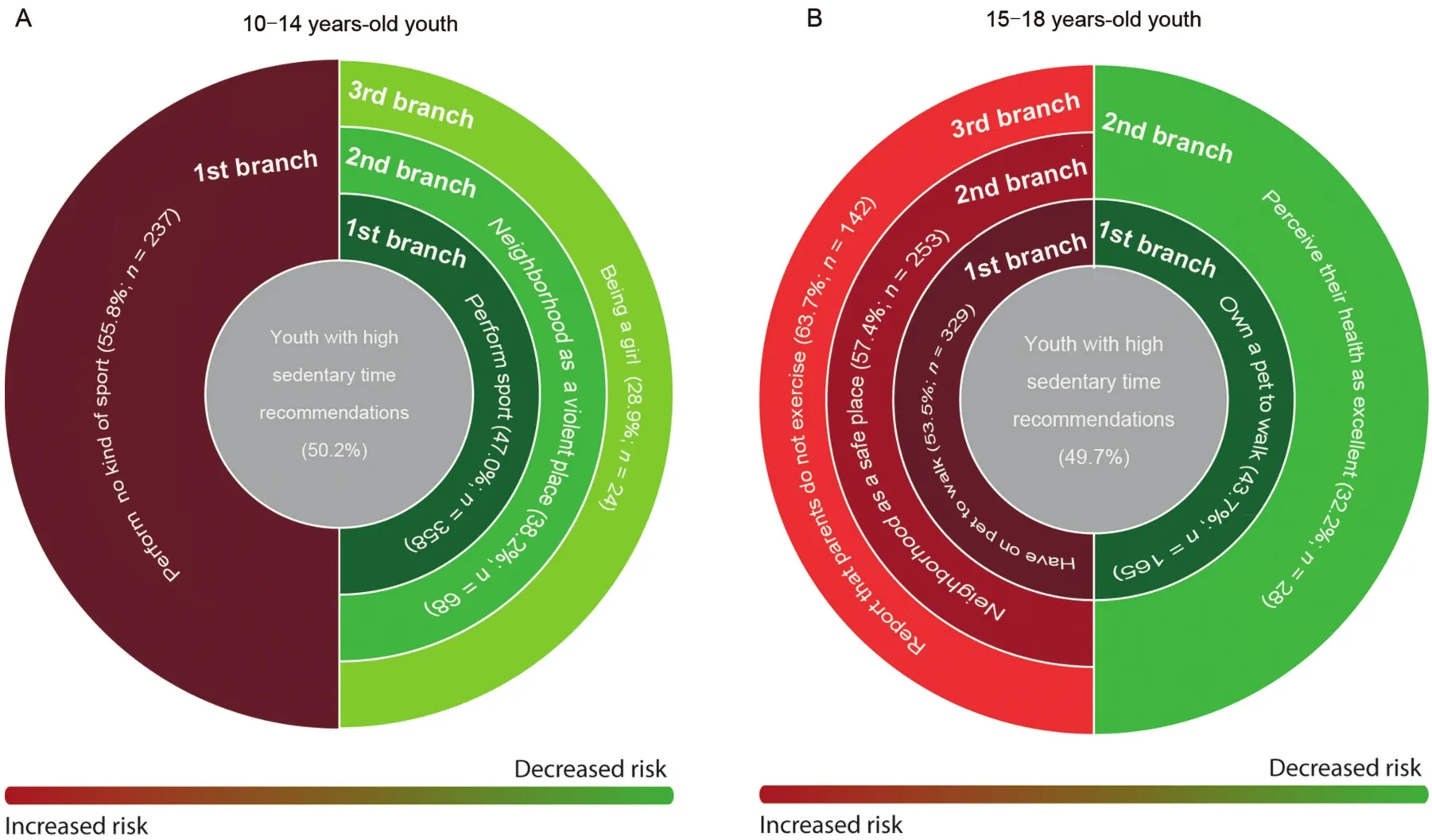

Details on the 2179 participants’demographic characteristics by age group are presented in Table 1.Almost all the participants were Portuguese(i.e.,97.4%of the overall sample),with only 57 youth(2.6%)being born in other countries but living in Portugal for a number of years.In the age group that was 10-14 years old,29.8%of the participants were currently studying in the 5th and 6th grades,whereas 70.2%were in the 7th to 9th grades.In the age group that was 15-18 years old,the majority of the participants were in high school(the 10th grade:49.4%;the 11th grade:26.5%;the 12th grade:24.1%).Overall,in the younger group,20.7%attained MVPA recommendations,whereas 50.2%were classi fied as being highly sedentary(≥50 percentile),and 40.4% spent more than 2 h/day in CST.In the older group,19.8%attained MVPA recommendations,49.7%were classi fied as being highly sedentary,and 62.1%spent more than 2 h/day in CST.

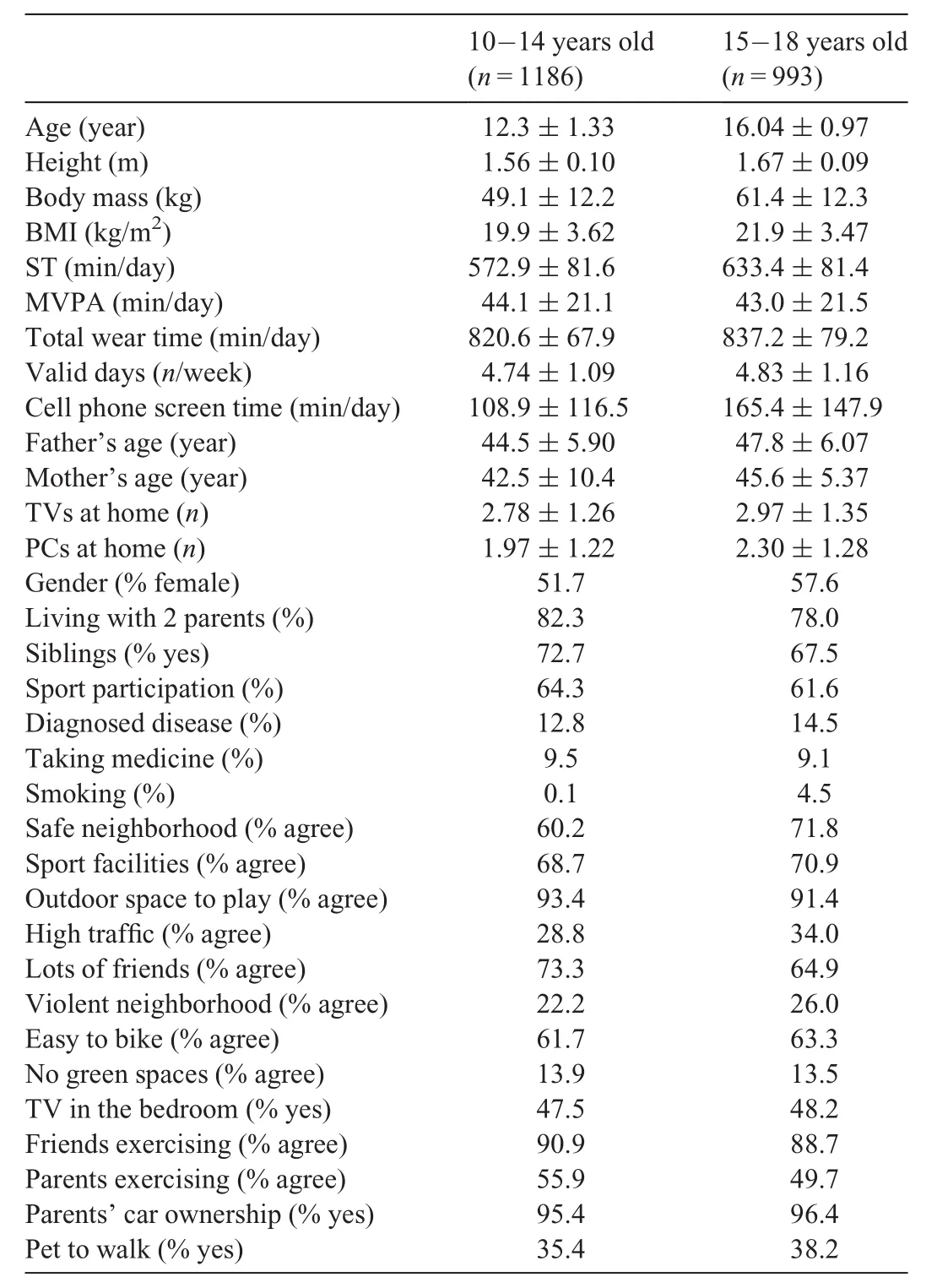

Based on the decision-tree model and as shown in Fig.1,in order to increase the odds of youth 10-14 years old being physically active(≥60 min/day),the correlates that were hierarchically most important were(1)being a boy,(2)performing any kind of sport,and(3)perceiving the neighborhood as a safe place,with 37.4%of youth ful filling all these factors and,thus,being classi fied as physically active.Those classi fied as most inactive were(1)girls,(2)reporting not having sport facilities in their neighborhoods,and(3)not perceiving the neighborhood as a safe place(0%chance of being active).Looking deeply into the analyses(Supplementary Fig.1),girls who reported having sport infrastructures nearby their houses and who were in the first 2 years of elementary school(i.e.,5th and 6th grades)had higher chances of being active(31.2%)compared to the older girls in the next 5 school years(12.2%).For the boys who did not perform any type of sport,their activity during recess at school was an important predictor of their achieving the PA guidelines,with boys who reported playing during recess having a 31.5%chance of being active compared to only a 12.4%chance when boys reported engaging mainly in sitting or standing activities during recess(Supplementary Fig.1).

As shown in Fig.1,in order to increase the odds of being physically active(≥60 min/day)between the ages of 15 and 18 years,youth have to(1)perform any kind of sport,(2)be a boy,and(3)perceive the neighborhood as having lots of traffic,with 46.2%of youth ful filling all these factors being classified as physically active.For being classi fied as inactive,the most important and unique correlate for this age group was“not performing any sport”(regardless of gender or any other correlate)(9.7%chance of being active).Examining in more detail the CHAID decision tree(Supplementary Fig.2),for the girls 15-18 years old who performed sports,living with both parents reduced the odds of being active(14.2%chance of being active)compared with the girls who lived with only 1 parent or any other family member(e.g.,aunt,grandmother)(26.7%chance of being active).

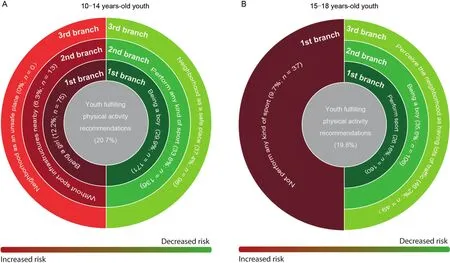

As shown in Fig.2,to be classi fied as low sedentary,youth 10-14 years old in elementary school must(1)perform any kind of sport,(2)perceive the neighborhood as a place where violence can occur,and(3)be a girl(71.1%chance of being classi fied as low sedentary if all these factors are ful filled).To be classi fied as high sedentary in this age group,the only and most important correlate was not partaking in any kind of sport,regardless of all the other correlates(55.8%chance of being high sedentary).The original decision tree can be found in Supplementary Fig.3.

As shown in Fig.2,having a pet to walk is the first correlate derived from the hierarchy that decreases the odds(from 53.5%to 43.7%)of youth 15-18 years old being classi fied as high sedentary.The odds of youth being classi fied as high sedentary further decrease if they perceive their health as excellent(32.2%).Youth 15-18 years old classi fied as high sedentary were those that(1)did not own a pet to walk,(2)perceived their neighborhood as a safe place,and(3)reported that parents do not exercise(63.7%chance of being high sedentary).Looking in more detail into the CHAID decision tree and its secondary branches(Supplementary Fig.4),for participants who did not have a pet to walk and simultaneously did not perceive their neighborhood as safe,the odds of being classi fied as high sedentary were higher(49.2%)if they lived with siblings compared to being an only child(32.1%).For youth 15-18 years old who simultaneously had a pet to walk and did not perceive their health to be excellent,those who reported having good cycling paths had lower odds of being in the high sedentary category(42.6%)compared to the those reporting not having good cycling paths in the neighborhood(54.6%)(Supplementary Fig.4).

Table 1 Participants’characteristics by age group(n=2179,mean± SD or%).

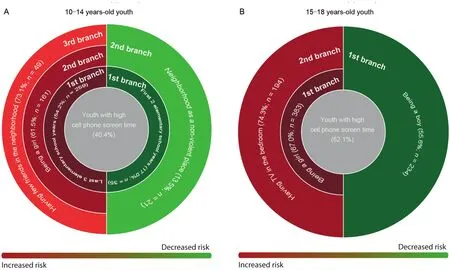

As shown in Fig.3,the most important correlate impacting the CST of youth 10-14 years old was the year in school,rising from the first 2 years(17%chance of spending more than 2 h/day)to the last 3 years(54.2%chance of spending more than 2 h/day).The lowest odds for spending more than 2 h/day in CST occurred when(1)youth were in the first 2 years of elementary school and(2)simultaneously did not perceive their neighborhood as a violent place(13.5%).The highest odds for youth 10-14 years old to spend more than 2 h/day in CST were when they(1)were in the last 3 years of elementary school,(2)were girls,and(3)reported that they did not have lots of friends in the neighborhood(73.1%).As shown in Supplementary Fig.5,for the girls 10-14 years old in the last 3 years of elementary school,having lots of friends living near their house reduced the odds of spending more than 2 h/day in CST from 73.1%to 57.4%.Finally,in the 6th grade,youth who spent their recess in active behaviors(i.e.,playing and walking)had lower odds of spending more than 2 h/day in CST(18.9%)compared to those spending their recess mostly in sitting and standing activities(Supplementary Fig.5).

Fig.1.Hierarchy of correlates favoring and reducing youth’s chances of ful filling physical activity recommendations by age group:(A)10-14 years old,(B)15-18 years old.

Fig.2.Hierarchy of correlates favoring and reducing youth’s chances of having high sedentary time by age group:(A)10-14 years old,(B)15-18 years old.

As shown in Fig.3,the highest odds for youth 15-18 years old to spend more than 2 h/day in CST was dependent on(1)being a girl and(2)simultaneously having a TV in the bedroom(74.3%).The lowest odds(55.6%)for spending more than 2 h/day in CST occurred when participants were boys,regardless of the other correlates.As shown in the CHAID decision tree(Supplementary Fig.6),for the girls who did not have a TV in the bedroom,being the only child increased the odds of spending more than 2 h/day in CST(70.9%)compared to those living with siblings(56.9%).

Fig.3.Hierarchy of correlates favoring and reducing youth’s chances of having high cell phone screen time by age group:(A)10-14 years old,(B)15-18 years old.

4.Discussion

The aim of this investigation was to use sensor-based ST,MVPA,and self-reported CST data from a large sample of youth,while taking into account the interactions among a variety of correlates comprising a socioecologic model.The novelty of this investigation is our use of a socioecologic approach that simultaneously considered correlates from individuals,social environments,and physical environments20while using sensor-based data for 2 independent health-related outcomes(i.e.,ST and MVPA)and a prevalent behavior in youth,CST.Findings from this investigation suggest that,depending on the speci fic aims,outcomes,and age categories,the hierarchy of impactful correlates changes,although the hierarchy for some correlates seem to repeat for certain behaviors.

Gender emerged as an important factor for MVPA and favored boys.This con firms previous findings suggesting that girls tend to be more inactive than boys.15,16A reduction in PA attractiveness(enjoyment)and a lower psychosocial pro file of girls approaching biologic maturity may explain the decreasing rate of PA participation.40However,for sensorbased ST,especially in the 10-14-year-old youths,we found an opposite trend,with girls being less sedentary than boys,which contradicts prior findings showing that girls spend more time in sensor-based ST.41On the other hand,being a girl increased the odds of spending more than 2 h/day in CST in both age categories,which is in accordance with the existing evidence showing that girls are more prone to spend higher amounts of time in screen-based activities.42,43Thus,based on our findings and those from prior studies,44gender plays varying roles depending on the speci fic behavior being investigated.This reinforces the necessity for future studies to use a socioecologic approach when exploring the role of gender as a correlate for sensor-based MVPA,ST,and SBs,such as CST.

Perceived neighborhood safety also presented as a crucial correlate for determining CST and sensor-based ST and MVPA levels in youth,which supports the findings from previous investigations.17,32,45-47However,the direction of the association between perceived neighborhood safety and sensor-based MVPA and ST was inconsistent.Similar to previous f i ndings,6,8neighborhood safety was an important correlate favoring MVPA in the younger age group.In our study,however,the perception among older active boys that their neighborhood had lots of traf fic was a positive correlate for increased MVPA levels,which contradicts previous evidence suggesting that more traf fic is inversely associated with MVPA levels in youth.48We hypothesize that active boys may spend more time in the streets and in the surrounding areas of their neighborhoods,leading them to potentially pay more attention to the traf fic than their less active peers,thus making them more prone to report neighborhood traf fic.Also contrary to the literature,17our study found that perceived neighborhood safety increased the risk of being highly sedentary in the older group,whereas perceived neighborhood violence decreased ST in the younger group.Inconsistencies in the role that neighborhood safety plays in the levels of MVPA and ST among youth have been previously reported,49and it has been suggested that this may be partly attributed to measurement limitations.49The fact that many investigations employ generic safety measurements that make implicit references to crime or use composite variables that lack speci ficity are some of the proposed reasons.49Our results suggest that a sense of neighborhood security can drive youth to spend more time in MVPA but can also simultaneously promote more ST outside their homes,whereas a perception that the environment is unsafe favors low-intensity,nonsedentary activities instead of ST.

Sport participation was an important correlate related to increased MVPA levels in both younger and older youth.Moreover,in the younger age group,sport participation was the most important correlate for reducing the odds of being sedentary,thus suggesting that sport participation may be important in both MVPA and ST.33Evidence suggests that an independence exists between ST and MVPA and their associations with health,43,50but our findings are in line with those from a previous investigation,33suggesting that sport participation can be both a strategy to reduce ST and to improve MVPA levels in youth,because these authors found that sport participation emerged as a strong correlate of low screen-based SB in youth.33This suggests that sport participation may be a viable way to reduce SB,thus contradicting previous evidence suggesting that participation in sport appears to be unrelated to ST.50Furthermore,a lack of sport facilities nearby was identif i ed as the second most important correlate for decreasing youth’s chances of attaining MVPA recommendations.Our f i ndings concur with the findings from previous investigations,suggesting that having sport infrastructures nearby is an important factor favoring youth’s PA levels.51,52Proximity to sport facilities has been associated not only with higher levels of MVPA among youth,48,53but it also seems to moderate the associations between psychosocial factors(i.e.,support of friends or modeling by parents)and MVPA levels among youth.For example,the positive associations between youth’s MVPA and the norms support and attitudes of friends were strengthened for adolescents living in neighborhoods with highvs.low availability of PA resources.53

Previous evidence has highlighted the importance of family structure24,54and social correlates45,55in PA and ST levels.However,most studies have considered screen time to be a measure of SB,which does not cover all ST.Evidence on the impact of family structure on ST among youth in relation to data gathered through the use of sensor-based measures is scarce.56In our study,we found that living with a single parent and living with siblings impacted youth’s sensor-based MVPA,ST,and CST.Evidence suggests that parents’direct involvement(i.e.,instrumental support such as providing transport)and encouragement(i.e.,motivational support)are linked to youth’s MVPA levels.57Nevertheless,there is a significant degree of heterogeneity in the results from studies of the relationship of family structure and PA levels,58with one study finding that regardless of whether youth lived with both parents or with a single parent,it was a nondeterminant factor for PA levels of youth.15We found,however,that living with a single parent was associated with a higher chance of attaining MVPA recommendations.A potential explanation for this observation may be related to the fact that youth living with a single parent(i.e.,in cases in which parents are divorced)may be more prone to counteract parents’behaviors instead of emulating them.By acknowledging that most adults do not attain PA recommendations,one can hypothesize that living with both parents can increase the odds of following a“bad example”in terms of the parents’PA pro file.In fact,reporting that their parents did not exercise was the third most important correlate for increasing the odds of being classi fied as high sedentary,which emphasizes that in addition to family structure,family behaviors can also impact youth’s ST.42,59

Beyond the in fluence of parents,siblings can have an effect on youth’s ST.Mixed findings on the association between ST and having siblings have been reported in the literature,with some investigations showing that having siblings increases ST,whereas other studies show the opposite effect.56In the older youth,we found that living with siblings increased the odds of being sedentary.It is possible that when there are no siblings living in the same house,youth will have to search for other ways to socialize(e.g.,friends),which can imply leaving the house,thus potentially reducing their ST.However,we found that being a girl without siblings increased CST.One can hypothesize that girls without siblings may need to contact friends and other people not living in their homes,thus potentially causing them to spend more time on their cell phones.Our findings suggest that a speci fic feature(i.e.,not having siblings)may be protective for a speci fic behavior(i.e.,sensor-based ST)but still promote other sedentary pursuits(e.g.,CST).This reinforces the importance of examining several outcomes(i.e.,sensor-based ST,self-reported CST)in the same dataset so that discrepancies are not attributed to different population groups.For example,having friends living nearby(i.e.,a social correlate)was found to in fluence CST.Our findings extend those of previous investigations that have shown that not having close neighbors increases overall SB,55thus supporting the idea that a youth’s social network is paramount.Youth who do not have friends living close by may spend more time on their cell phones in order to maintain contact with their friends.

Other important correlates of youth PA and ST that were identi fied in the current investigation included owning a pet to walk,perception of health,and having a TV in the bedroom.In older youth,owning a pet to walk decreased the odds of being classi fied as high sedentary.To our knowledge,no previous investigation has considered this correlate for sensor-based ST levels in youth.However,a previous study did find that youth who walked a dog had 7%-8%more min/day of MVPA than non-dog walkers.60In addition to owning a dog,youth who perceived their health as excellent were those presenting lower ST,which is similar to findings for the general population.15People who perceive that their health as being good have a greater predisposition to engage in nonsedentary activities,thus decreasing their time spent in sedentary pursuits.15Parents are naturally concerned with their youth’s health,but educators and parents should additionally be aware of their youth’s perceptions of their health because this may be a correlate for their ST levels.Last,we found that CST was increased in older girls who had a TV in their bedroom.Having a TV in the bedroom has consistently been associated with higher screen time.18,30,46,61Thus,our results con firm the findings from previous studies.There is also evidence showing that greater access to bedroom media sources is associated with higher screen time.42Therefore,parents can play a decisional role in youth’s screen time by simply removing or at least limiting media sources in their youth’s bedrooms.Notably,a previous investigation found that decreasing the number of TVs at home could improve the ST pro files of youth,47and another recent investigation found that media accessibility can increase overall screen time.31

The findings from the present investigation contribute greatly to the field because evidence is scarce in relation to socioecologic and other correlates of youth’s PA and ST derived from sensor-based measurements,as well their selfreported CST.The use of the CHAID analysis allowed us to examine different levels of correlates in the same dataset,which is paramount for establishing an order of importance from a high number of multidomain correlates.However,this study is not without limitations.First,there is subjectivity associated with the questionnaires that were used to collect information on the correlates,even though this is the only way of collecting some of these data.In addition,the cross-sectional nature of the data does not allow for the establishment of causality.Thus,future studies should similarly use sensorbased metrics for ST and PA outcomes and aim for longitudinal protocols so that causality can be established.Finally,even though we included 31 correlates from distinct domains,there may be other relevant factors that we did not include.

5.Conclusion

Distinctive factors from the socioecologic model can in fluence sensor-based ST,PA,and self-reported CST in youth,such as sociodemographic correlates(i.e.,gender,sport participation),environmental correlates(i.e.,neighborhood safety,access to sport facilities),and family and social correlates(i.e.,presence of siblings,parents’exercise habits,friends living nearby,having a pet to walk),as well as some other more speci fic correlates(i.e.,having a TV in the bedroom).Public and governmental strategies to counteract SB and boost youth’s PA levels should focus on girls,emphasize neighborhood safety and improved access to sport facilities,and promote overall sport participation,as well as extend these strategies to family and friends in order to change youth’s habits.Also,simple plans,such as endorsement of pet ownership and limiting access to TVs in the bedroom,may help to attain better health pro files in today’s youth.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the participants for their time and effort.This investigation was conducted at the Interdisciplinary Center of the Study of Human Performance(CIPER),I&D 472(UID/DTP/00447/2019),Faculty of Human Kinetics of the University of Lisbon,and supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology,the Portuguese Ministry of Science.PBJ is supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology(SFRH/BPD/115977/2016),and DHN is supported by a grant from ComitOlmpico de Portugal(doctoral scholarship-COP).

Authors’contributions

PBJ,JPM,GBR,and DHN conducted fieldwork;LBS developed the conceptual model and conducted mapping;PBJ and MHR performed data analyses.All authors discussed the results,contributed to the writing of the manuscript.All authors have read and approved the final manuscript,and agree with the order of the presentation of authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2020.03.003.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2021年1期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2021年1期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Author biographies of Editor-in-Chief’s choice

- Association between physical activity and digestive-system cancer:An updated systematic review and meta-analysisT

- Risk factors for overuse injuries in short-and long-distance running:A systematic reviewT

- Physical exercise may exert its therapeutic in fluence on Alzheimer’s disease through the reversal of mitochondrial dysfunction via SIRT1-FOXO1/3-PINK1-Parkin-mediated mitophagyT

- Exercise interventions for older adults:A systematic review of meta-analysesT

- he mirror’s curse:Weight perceptions mediate the link between physical activity and life satisfaction among 727,865 teens in 44 countriesT