Exercise interventions for older adults:A systematic review of meta-analysesT

Cluio Di Lorito*,Annll LongArin ByrnRown H.Hrwoo,John R.F.GlmnStfn Shnir,Pip LognAlssnro Boso,Vronik vn r WrtT

aDivision of Rehabilitation,Ageing,and Wellbeing,School of Medicine,University of Nottingham,Nottingham NG7 2UH,UK

bDivision of Health Sciences,School of Medicine,University of Nottingham,Nottingham NG7 2UH,UK

cInstitute of Movement and Neurosciences,German Sport University,Cologne 50933,Germany

dDivision of Psychiatry and Applied Psychology,School of Medicine,University of Nottingham,Nottingham NG7 2UH,UK

eCenter for Methodology and Health Research,Department of General Medicine,Preventive and Rehabilitative Medicine,Philipps-Universitt Marburg,Marburg 35032,Germany

Received 19 January 2020;revised 24 March 2020;accepted 26 April 2020 Available online 7 June 2020

2095-2546/©2021 Published by Elsevier B.V.on behalf of Shanghai University of Sport.This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license.(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

Abstract Background:The evidence concerning which physical exercise characteristics are most effective for older adults is fragmented.We aimed to characterize the extent of this diversity and inconsistency and identify future directions for research by undertaking a systematic review of metaanalyses of exercise interventions in older adults.Methods:We searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews,PsycInfo,MEDLINE,Embase,CINAHL,AMED,SPORTDiscus,and Web of Science for articles that met the following criteria:(1)meta-analyses that synthesized measures of improvement(e.g.,effect sizes)on any outcome identi fied in studies of exercise interventions;(2)participants in the studies meta-analyzed were adults aged 65+or had a mean age of 70+;(3)meta-analyses that included studies of any type of exercise,including its duration,frequency,intensity,and mode of delivery;(4)interventions that included multiple components(e.g.,exercise and cognitive stimulation),with effect sizes that were computed separately for the exercise component;and(5)meta-analyses that were published in any year or language.The characteristics of the reviews,of the interventions,and of the parameters improved through exercise were reported through narrative synthesis.Identi fication of the interventions linked to the largest improvements was carried out by identifying the highest values for improvement recorded across the reviews.The study included 56 meta-analyses that were heterogeneous in relation to population,sample size,settings,outcomes,and intervention characteristics.Results:The largest effect sizes for improvement were found for resistance training,meditative movement interventions,and exercise-based active videogames.Conclusion:The review identi fied important gaps in research,including a lack of studies investigating the bene fits of group interventions,the characteristics of professionals delivering the interventions associated with better outcomes,and the impact of motivational strategies and of significant others(e.g.,carers)on intervention delivery and outcomes.

Keywords:Intervention;Meta-analyses;Old;Physical exercise;Systematic review

1.Introduction

Demographics are changing globally with the shift toward an aging population.Over the past 50 years,the number of adults over age 65 has tripled,and by 2050,older people will represent 25%of the population worldwide.1-3

Despite advances in medicine,health care,and social conditions,longer life expectancy is not necessarily matched with increased health.4Engagement in exercise has multiple health bene fits and can slow some of the negative effects of aging.5For example,exercise improves physiological outcomes in older people who have gone through long periods of sedentary lifestyle,6nonagenarians,7and older individuals with frailty8or sarcopenia.9Exercise is de fined as“planned,structured and repetitive physical activity”.10

In recent years,guidelines have been developed for exercise levels appropriate for older adults.The World Health Organization recommends that older adults engage in≥150 min of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise or≥75 min of vigorousintensity aerobic exercise per week or an equivalent combination of the two.11To produce numerous bene fits,including cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness,this exercise should be performed in bouts of 10 min or more.11,12Weight-bearing activities can help maintain bone and functional health.12Staying physically active also reduces noncommunicable disease,depression,and cognitive decline.Additional health bene fits can be obtained by gradually increasing the weekly time dedicated to exercise.11,12

Older adults who have poor mobility should still engage in exercise at least 3 times a week to strengthen major muscle groups,maintain or improve balance,and reduce the risk of falls.11,12Older adults who cannot exercise due to poor health conditions should,as much as possible,engage in physical activity that is commensurate with their abilities.11The UK Chief Medical Of ficers’Physical Activity Guidelines state that even a minimal level of physical activity(e.g.,standing),as opposed to being sedentary,generates some health bene fits.12

These guidelines re flect the widespread consensus that“If physical activity were a drug,we would refer to it as a miracle cure,due to the great many illnesses it can prevent and help treat.”12Despite the overall view that exercise is bene ficial,the evidence around which exercise characteristics(e.g.,type of exercise,intensity,duration,and frequency)are most effective for older adults is fragmented.Different types of exercise interventions have been delivered to healthy13-33and nonhealthy older adults34-46in different types of settings(e.g.,community,23,47residential care homes,38,39private homes24-27)and with various types of support(e.g.,provided by professionals16or students41).These interventions are aimed at improving a range of outcome measurements,such as physical functioning,13,33,48falls,14,34and mental functioning.29,44,45The diversity of these interventions generates inconsistent findings in studies that examine them and makes comparisons among different studies(and exercise con figurations)highly challenging.

We sought to characterize the extent of this diversity and inconsistency in study findings and to identify future directions for practice and research by undertaking a systematic review and synthesis of the literature on exercise among older people.The research questions we posed were:

TedP·How diverse are the characteristics of exercise interventions for older adults?

·How inconsistent are the findings around outcome parameters and improvement of health through exercise interventions?

·Is it possible to determine which interventions are most effective in achieving certain outcome parameters?

We aimed to answer these questions through the following goals:

TedP·Objective 1:reporting on the characteristics of exercise interventions for older adults.

·Objective 2:investigating which outcome parameters significantly improved through various intervention characteristics(e.g.,type and duration).

·Objective 3:identifying and ranking the interventions that are linked to the greatest improvements in outcome parameters.

2.Methods

A systematic literature review of meta-analyses was deemed appropriate to synthesize and organize into a manageable format the wealth of evidence available from multiple sources.49The review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses(PRISMA)statement.50Supplementary Table 1 shows where in our review each of the items in the checklist was addressed.A protocol for our review was published in the international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews in health and social care(PROSPERO).51

2.1.Search

The search strategy(Supplementary Table 2)was based on the Population,Intervention,Comparison,Outcome worksheet for conducting systematic reviews52and was developed by an expert librarian from the University of Nottingham.Two searches were performed(one in December 2018 and one in March 2020)in 8 databases:the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews,PsycInfo,MEDLINE,Embase,CINAHL,AMED,SPORTDiscus,and Web of Science.

2.2.Study selection and appraisal

All initial records were imported into Endnote.Duplicate records were removed.Three authors(CDL,AL,and VvdW)carried out title and abstract screening and eliminated ineligible studies.Each record was independently screened by 2 authors to ensure accuracy in selection.The same authors then screened the full texts of the remaining records against the inclusion/exclusion criteria(see below).Each record was,again,independently screened by 2 authors,and any disagreement was discussed to reach consensus.The number of records excluded and the reasons for exclusion were recorded.The references of the included reviews were screened to identify additional eligible studies.

2.2.1.Inclusion criteria

The literature review we conducted included:

TedP·Meta-analyses that synthesized measures of improvement(e.g.,effect sizes)on any outcome identi fied in studies of exercise interventions.An operational de finition of exercise is given in the Introduction Section.

·Meta-analyses that included studies of any type of exercise,including its duration,frequency,intensity,and mode of delivery.If the intervention included multiple components(e.g.,exercise and cognitive stimulation),effect sizes must have been computed separately for the exercise component.T

·Meta-analyses of studies in which participants were 65 years of age or older,or if the age inclusion criterion for the study was below 65 years of age or was not reported,the overall sample mean for age had to be at least 70 years old.

·Meta-analyses that were published in any year or language.

2.2.2.Exclusion criteria

The review we conducted excluded:

TedP·Literature reviews that did not include meta-analyse data;empirical studies;conference abstracts;or any other type of paper(e.g.,editorials).

·Literature reviews of studies in which participants were younger than 65 years of age,or,if the age inclusion criterion of the review was younger than 65 years of age or not reported,the overall sample mean was also below 70 years of age.

·Literature reviews that did not include an exercise component(e.g.,studies focused only on functional ability or physical activity).

2.3.Study-quality appraisal

Three raters(CDL,AL,and VvdW)independently assessed the quality of the included reviews using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme(CASP)checklist for systematic reviews.53Each article was appraised by 1 rater only.The highest possible score of the quality appraisal was 10,with higher scores showing higher quality.

2.4.Data extraction and synthesis

Data extraction was guided by the 3 objectives.Anad hocform,informed by the Cochrane data extraction form,54was used.The form was first piloted in a random sample of 3 reviews and then was used to extract study characteristics(i.e.,author,year,number of studies included,population,sample size,and participants’ages),interventions characteristics(i.e.,setting,type of intervention,duration,and frequency),and findings from the meta-analyses(review outcomes and measures of improvements).The data were extracted by the main author(CDL)and checked for accuracy by 2 other authors(AL and VvdW).

The characteristics of the reviews and of the interventions(Objective 1)were reported through narrative synthesis.In relation to the parameters improved through exercise(Objective 2),1 author(CDL)synthesized the data into outcomes as they emerged from the individual reviews.The outcomes were then grouped by the same author into themes(i.e.,umbrella outcomes).The process was checked for accuracy by 2 authors(AL and VvdW).Identi fication of the interventions linked to the largest improvement in outcome parameters(Objective 3)was carried out by identifying the highest values for improvement byoutcome,recorded across the reviews.

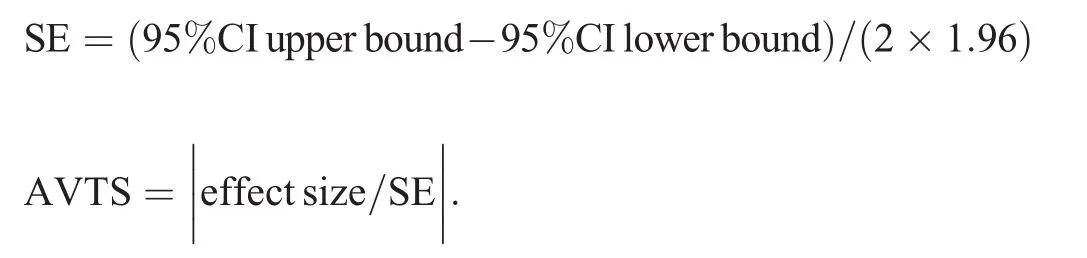

Different studies used different measures to report on effect size(Table 1).To assist with comparing effect sizes across the various studies,absolute value test statistics(AVTS)were calculated following the procedure outlined by Altman and Bland.55AVTS are a measure of statistical signi ficance regarding the strength of the effect size(i.e.,the larger the AVTS the more significant the effect).Using the effect-size point estimates and their corresponding 95%con fidence intervals(95%CIs),we calculated the standard error and AVTS for each result as follows:

Where the underlying measure was an odds ratio or a risk ratio,we first log-transformed the effect sizes and corresponding 95%CI before calculating their standard errors and AVTS.Once the AVTS for each study were computed,we then aggregated them by outcome/exercise/sample types using means and medians to aid our interpretation of the results.This allowed us to rank the interventions based on their aggregated effect sizes.

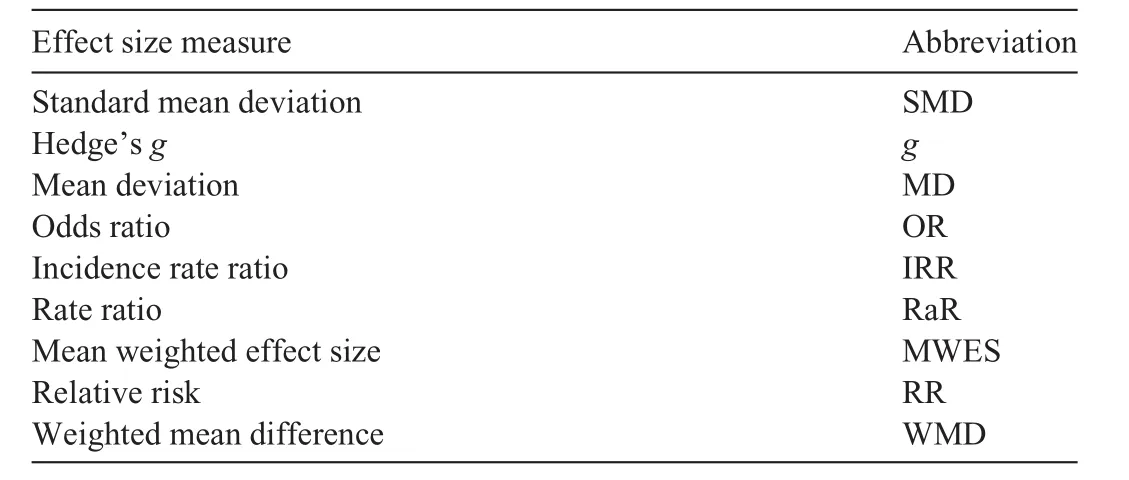

Table 1 Measures for effect sizes used in the studies.

3.Results

3.1.Study selection

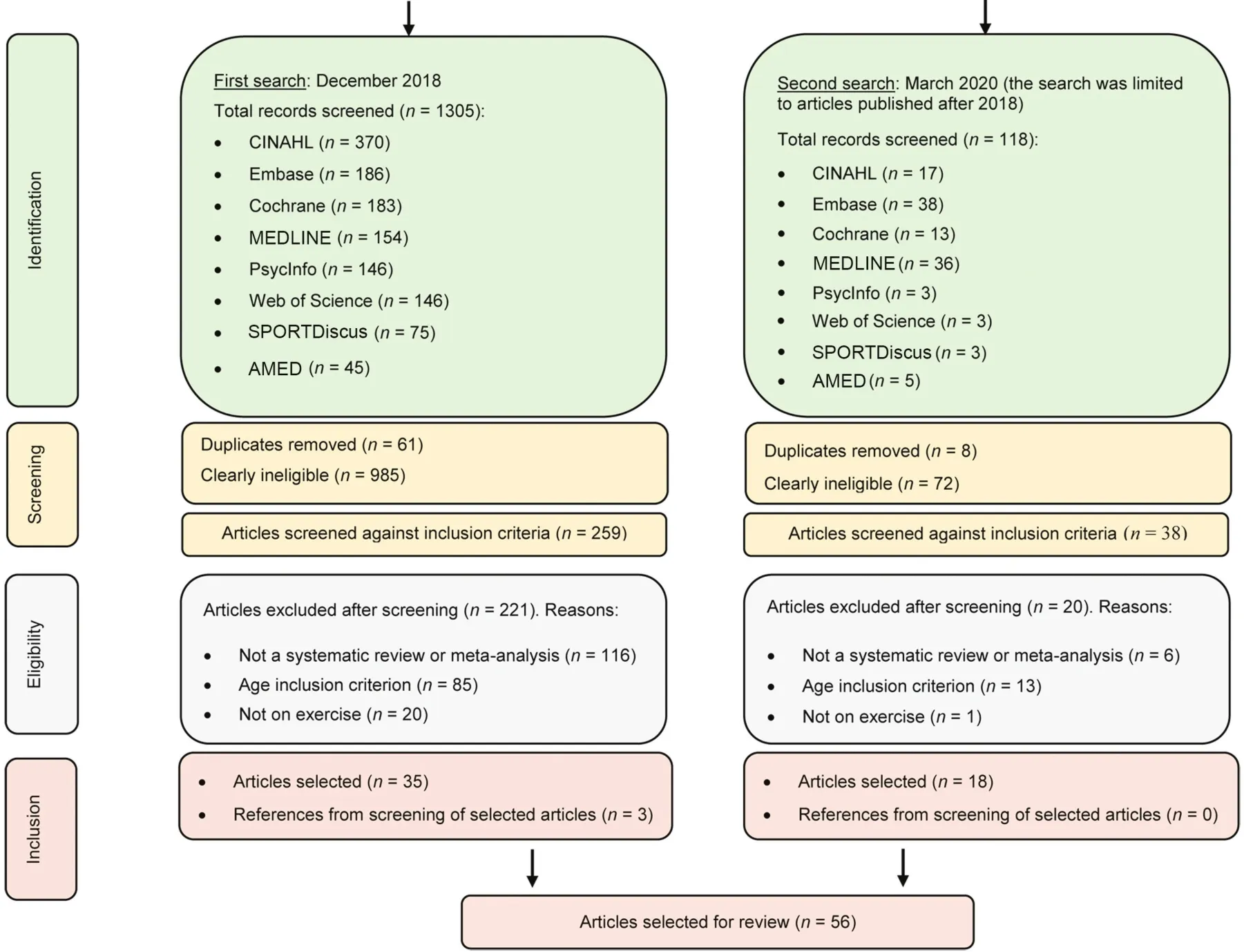

The initial search(December 2018)retrieved 1305 sources.Upon title and abstract screening,985 were deemed ineligible,and 61 were removed because they were duplicates.The full texts of 259 sources were screened against the inclusion/exclusion criteria.A total of 116 sources were removed because they were not meta-analyses,85 were removed because they had an age inclusion criterion below 65 or a mean age below 70,and 20 were removed because they did not involve exercise interventions.A total of 35 meta-analyses were included.After screening the reference lists of the included meta-analyses,3 additional meta-analyses were added,for a total of 38.

The second search(March 2020)limited sources to those published between December 2018(the ending month and year of the initial search)and March 2020.The search retrieved 118 sources.Upon title and abstract screening,72 were deemed ineligible,and 8 were removed because they were duplicates.The full texts of 38 sources were screened against the inclusion/exclusion criteria.Of these sources,6 were removed because they were not meta-analyses,13 were removed because they had an age inclusion criterion below 65 or a mean age below 70,and one was removed because it did not involve an exercise intervention.The 18 meta-analyses identi fied as eligible from the second search were added to the 38 identi fied in the first search,for a total of 56 meta-analyses included in our review.

Fig.1.Selection of papers.

Study selection is reported in Fig.1 through a PRISMA flow diagram.50

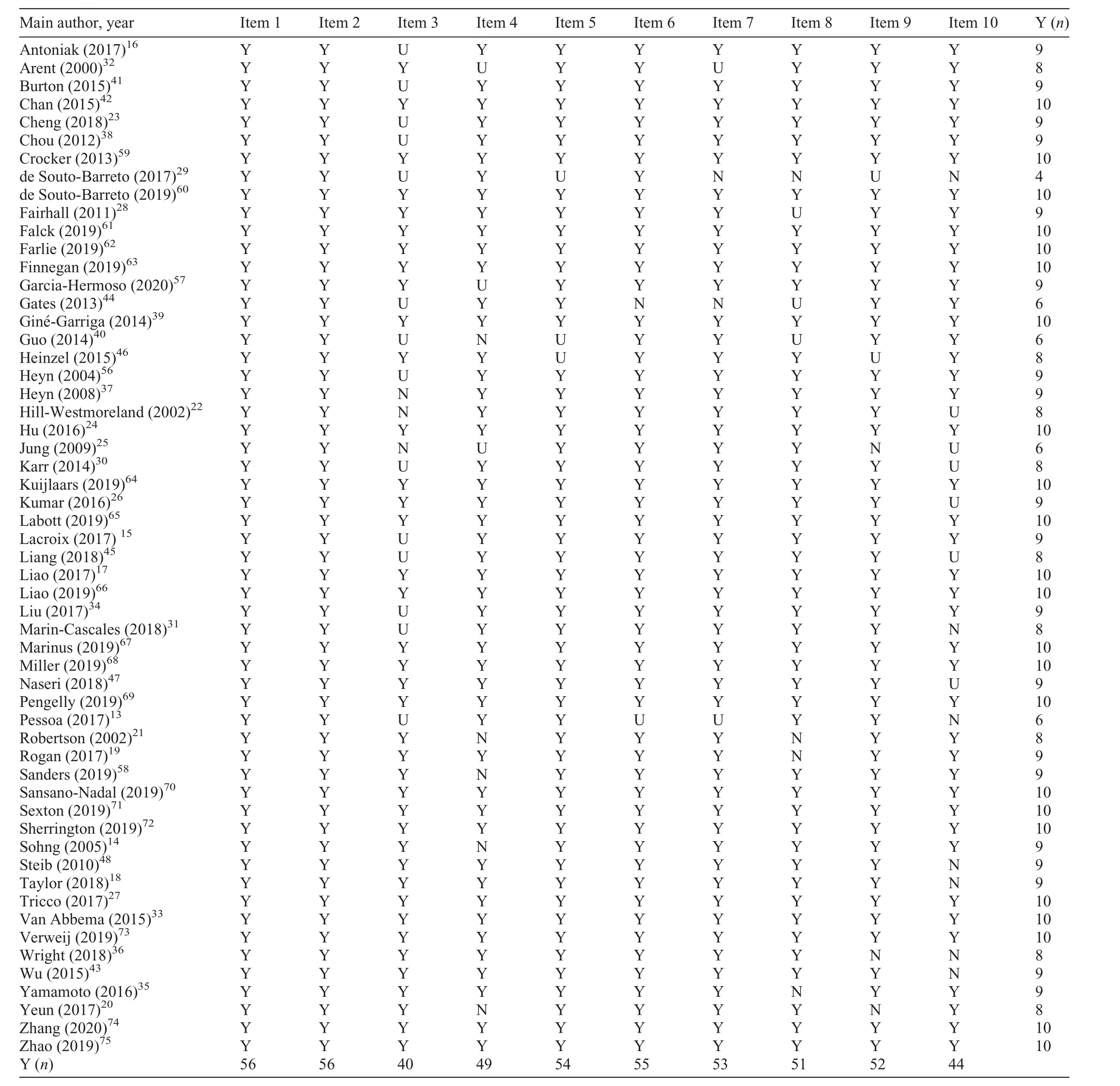

3.2.Study quality appraisal

Results from the quality appraisal are reported in Table 2.One review(2%)scored 4 points,294 reviews(7%)scored 6 points,13,25,40,449 reviews (16%) scored 8 points,20-22,30-32,36,45,4619 reviews (34%) scored 9 points,14-16,18,19,23,26,28,34,35,37,38,41,43,47,48,56-58and 23(41%)scored 10 points.17,27,33,39,42,59-75The items with the highest scores had clarity in the focus of the review and had higher scores for the appropriateness of included papers(n=56,100%).The items with lowest scores had lower scores for the inclusion of all relevant studies(n=40;71%)and for balance between bene fits and costs(n=44;79%).

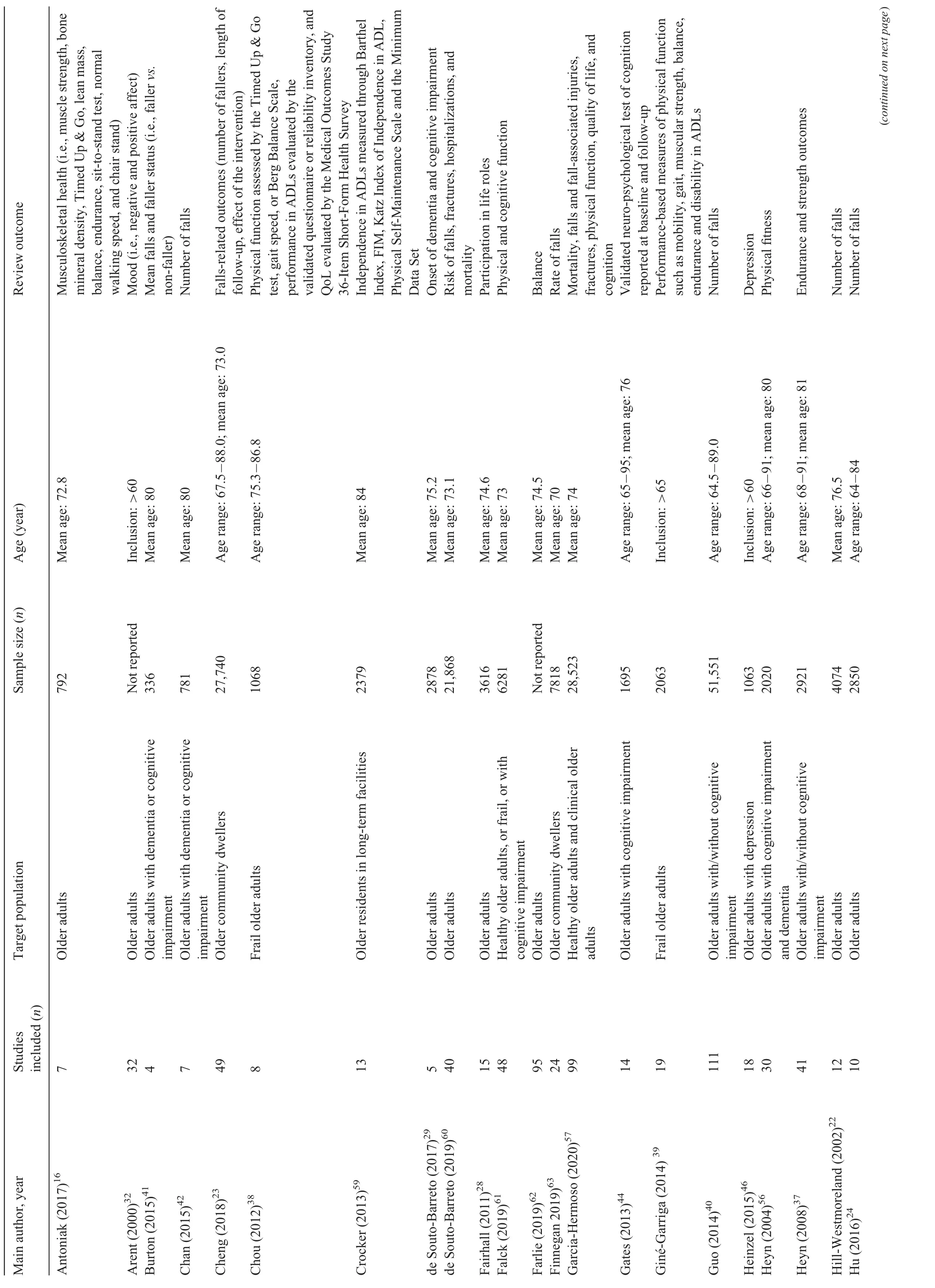

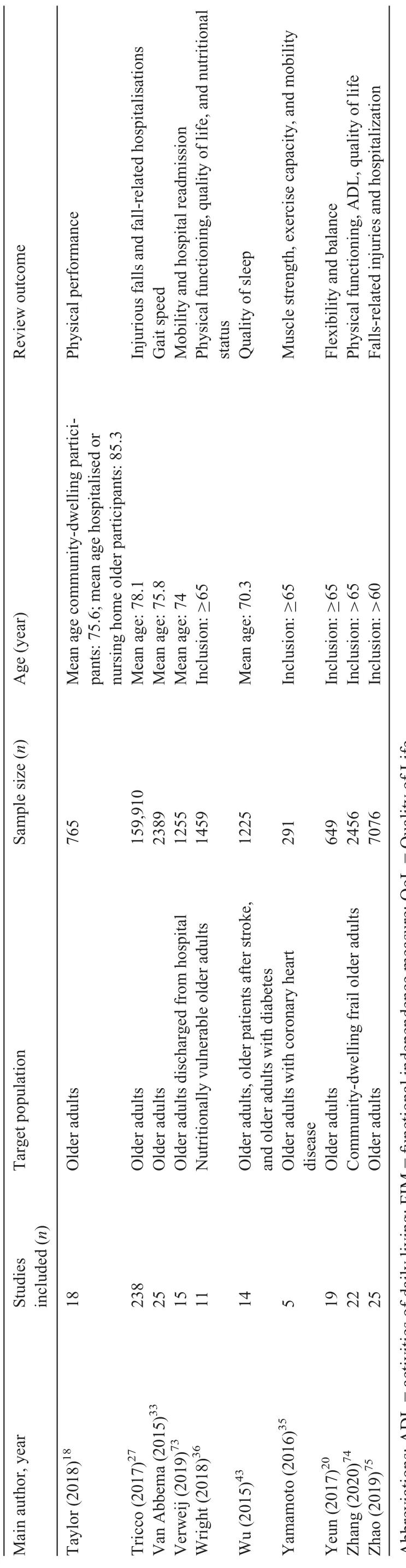

3.3.Review characteristics

The characteristics of the included reviews are reported in Table 3.The reviews were conducted between 2000 and 2020.They were all inEnglish,except for one in Portuguese.34The number of studies included in the meta-analyses ranged from 441to 23827(mean=28,SD=38).The reviews focused on healthy older adults(n=33;59%),13-26,28-33,47,48,57,58,60-63,65,67,70,72,75older adults with physical health problems(including reduced physical capacity and frailty)(n=15;27%),34-36,38,39,43,57,61,64,66,69,71-74people with cognitive impairment or dementia (n=9;16%),37,56,40-42,44,45,58,61olderadultswithmentalhealthconditions(i.e.,depression)(n=2;4%),46,68and postmenopausal women(n=1;2%).31The age inclusion criteria varied:in half of the meta-analyses (n=29; 52%) it was 65 years old,13-16,18-21,24,26,27,30,31,35-37,39,44,48,56,57,63,64,68-71,73,74and in a third of the meta-analyses(n=22;39%)it was 60 years old.17,23,25,26,28,29,34,40,41,43,46,47,59-61,65-67,72-75A total of 32 reviews(57%)reported the mean age of the participants in the included studies (range=70-84,mean=75,SD=4).15-18,21-23,25-30,33,37,41-44,47,56-63,70-73Although the age-inclusion criterion was not reported in 3 meta-analyses(5%)38,42,45and was below 60 years of age in two of them(4%),58,62these 5 meta-analyses were still included in the review because the mean age of participants was above 70(per the inclusion criteria).

The number of participants included in the meta-analyses was notreportedin4cases(7%).13,19,32,62In the remainder of the cases,it ranged from 291 to 159,910(mean=6713;SD=26,415).Healthy older adults totaled 287,890;older adults with cognitive impairment/dementia totaled 63,100;older adults with physical health problems totaled 14,060;older adults with mental health conditions totaled 1659;and postmenopausal women totaled 462.

Table 2 Quality appraisal.

Table 3 Review characteristics, as reported in the individual studies.

Table 3 (Continued)

Table 3 (Continued)

In relation to study outcomes, 26 meta-analyses(46%)13-20,33-39,48,56,57,61,62,64-66,69,70,74focused on physical functioning(e.g.,strength),physical health,and physical exercise(including mobility); 18 (32%)14,21-27,34,40-42,47,57,60,63,72,73focused on falls-related outcomes(e.g.,number of falls),injuries,and mortality;10(18%)28,34,36,38,43,57,59,64,71,74focused on independence in activities of daily living(ADLs),quality of life,quality of sleep,and functioning in society(participation);10(18%)29,30,44,45,57,58,61,67,69,71focused on brain functioning(e.g.,cognition);3(5%)16,31,66focused on musculoskeletal health and bone density;and 3(5%)32,46,68focused on mood.

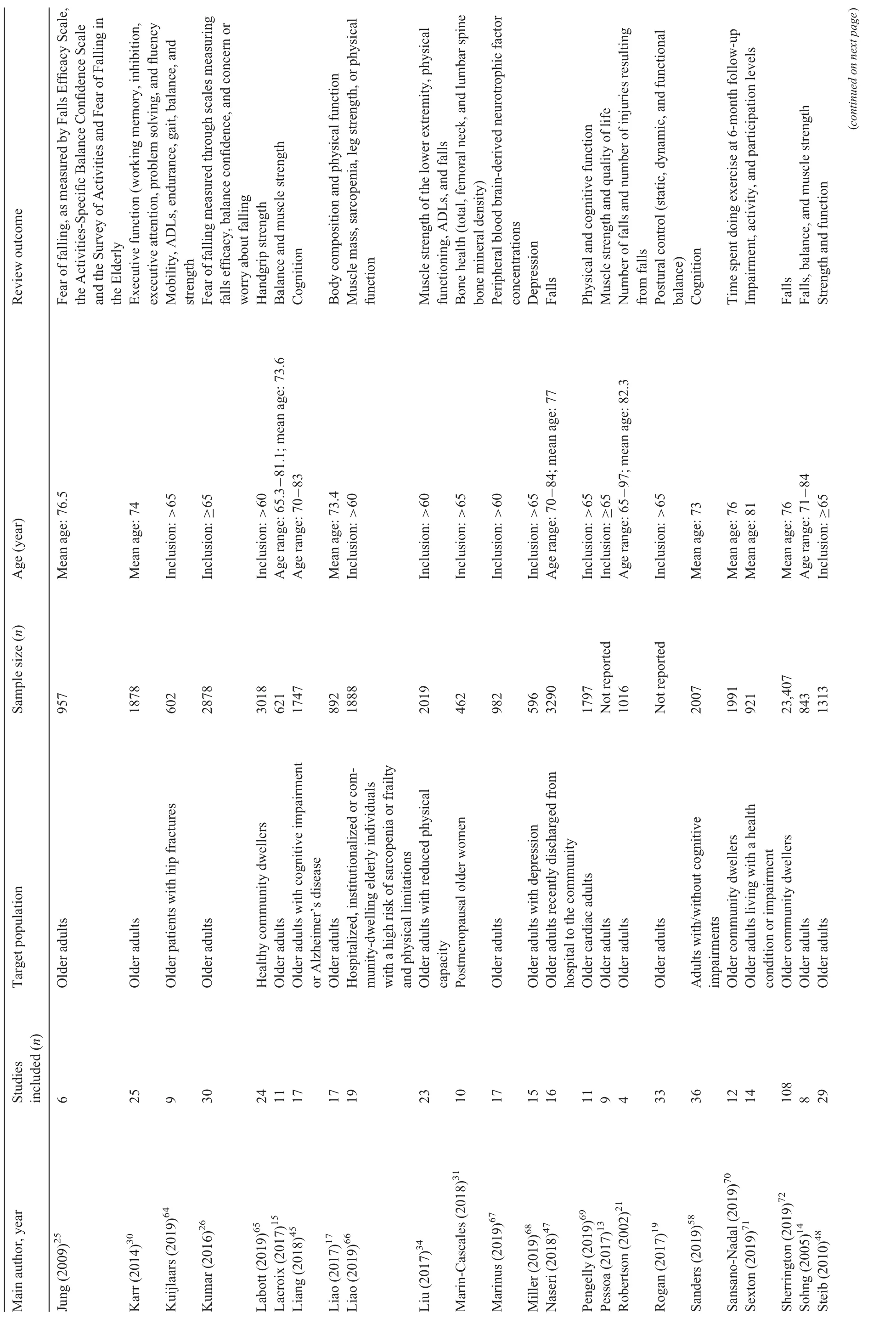

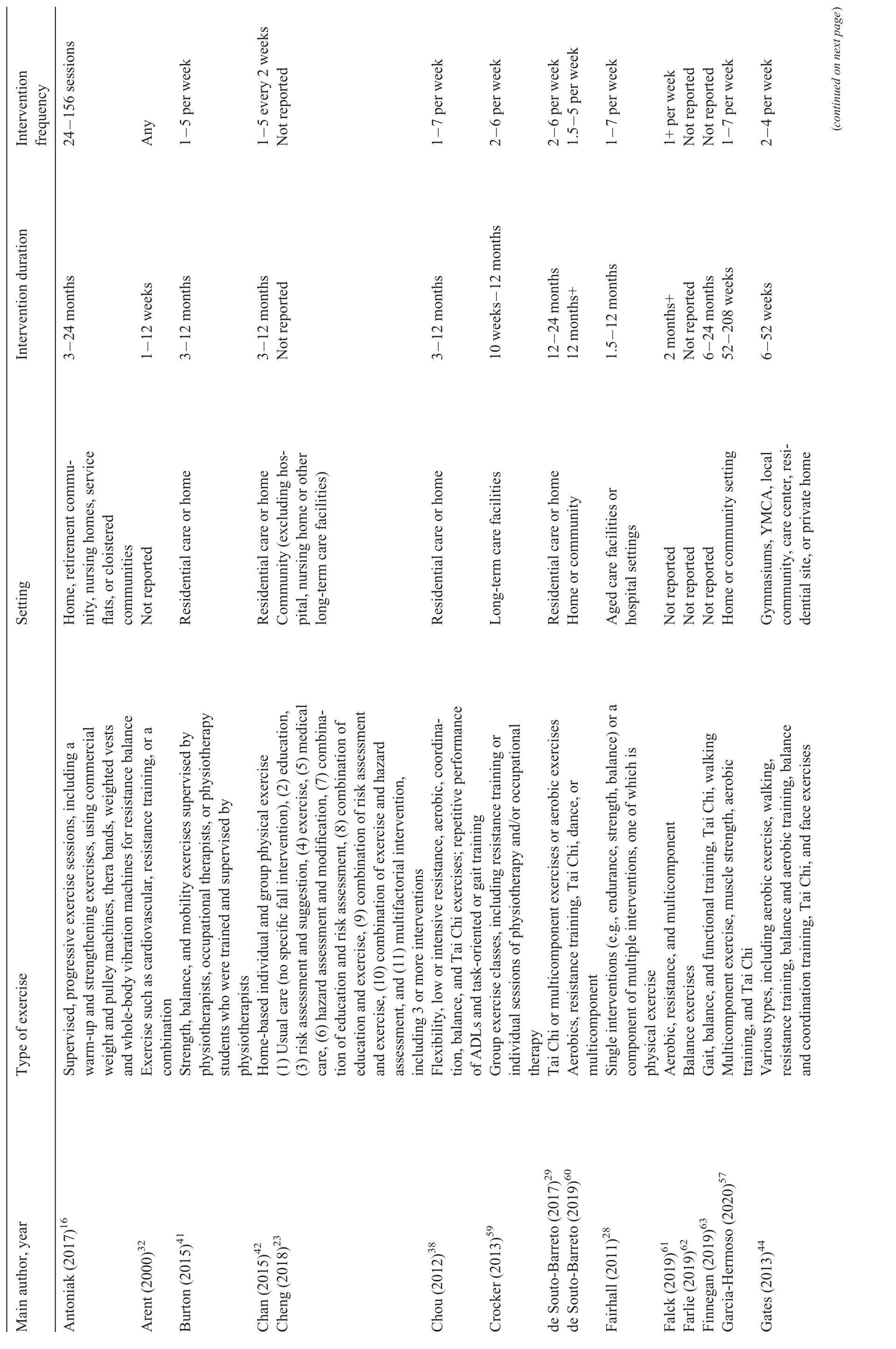

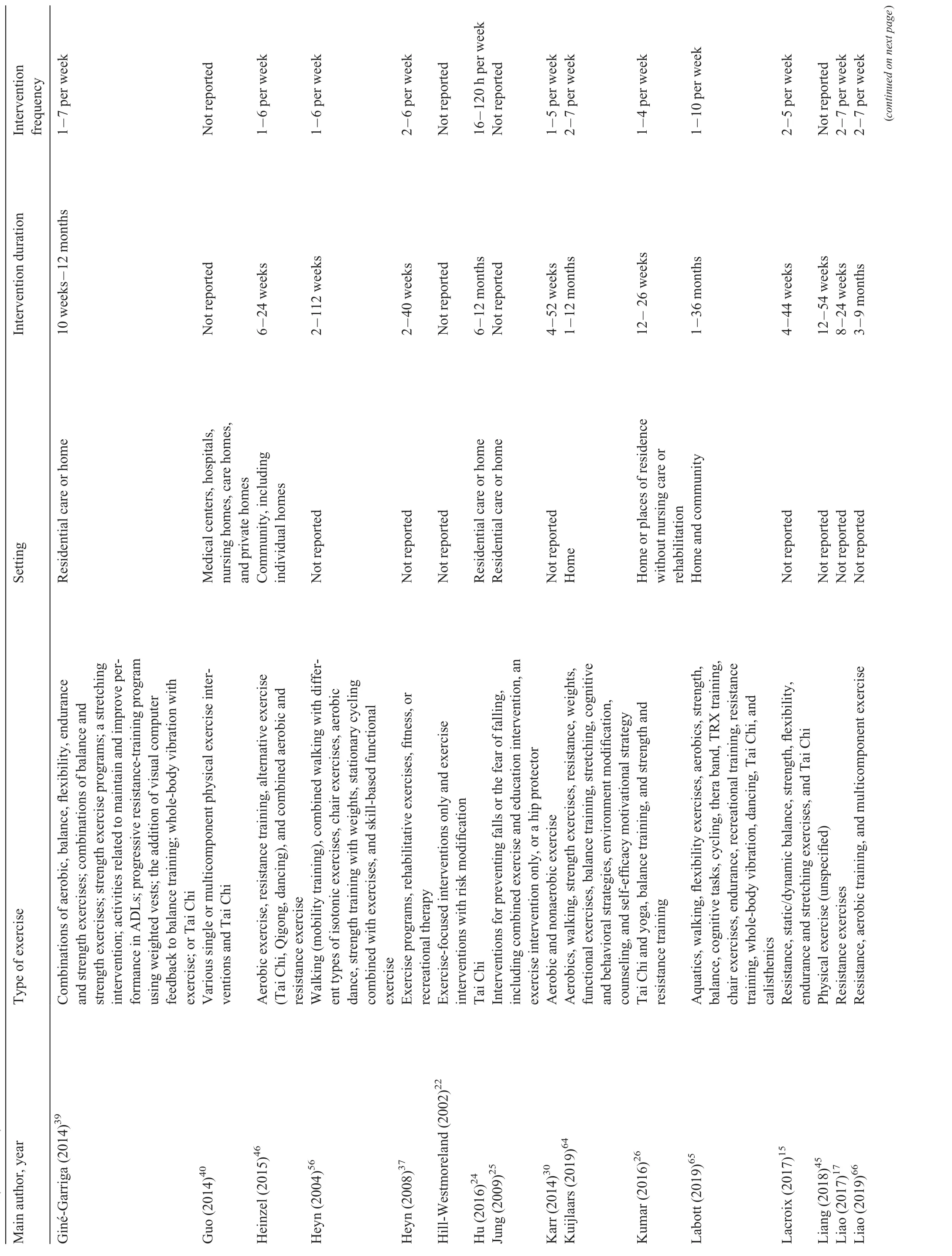

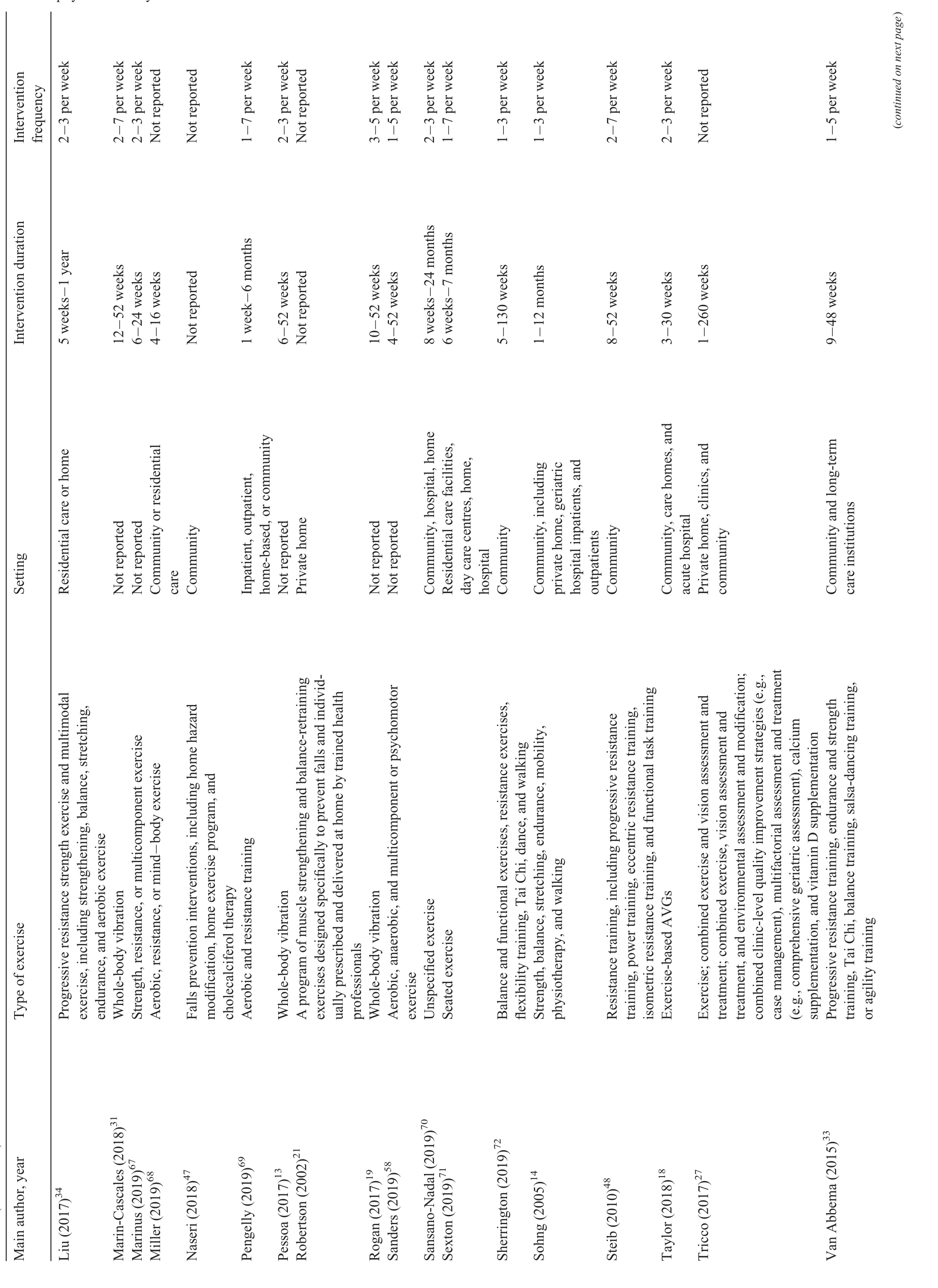

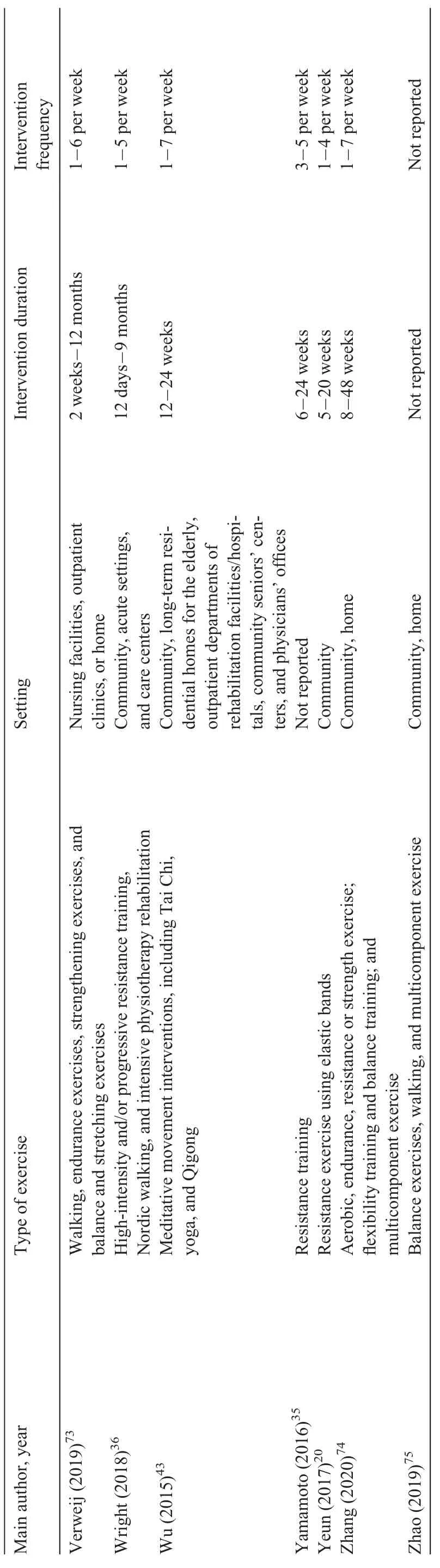

3.4.Objective 1:characteristics of exercise interventions

The characteristics of exercise interventions(Table 4)were extremely diverse.In relation to delivery setting,24(43%)interventions,14,16,21,24-27,29,34,38-42,44,46,60,64,65,70,71,73-75 were delivered in the participants’ homes, 14(25%)16,24-26,29,34,38-44,59were delivered in residential retirement homes,14(25%)14,18,21,23,27,36,43,44,46-48,68,69,71were delivered in community settings(e.g.,community centers),11(20%)14,18,27,28,36,40,43,69-71,73were delivered in health care settings(e.g.,hospitals),and 6(11%)16,18,28,33,36,40were delivered in care homes/nursing homes.The interventions were delivered in multiplesettingsin 50% ofthereviews(n=28).14,16,18,24-29,34,36,38-44,46,60,65,68-71,73-75The setting was not reported or speci fied in 19 reviews(34%).13,15,17,19,30-32,35,37,45,56-58,61-63,66,67

Intervention duration varied as well.A total of 9 interventions (16%) lasted up to 24 weeks (6 months);17,20,32,35,43,46,67,68,7326(46%)lasted between 25 and 52 weeks (6-12 months);13-15,18,19,24,26,28,30,31,33,34,38,39,41,42,44,48,56,58,59,64,66,69,71,74and 11(20%)lasted more than 53 weeks (more than 12 months).16,27,29,37,45,57,60,61,63,65,72This information was not reported in 9 reviews(16%).21-23,25,40,47,62,70,75Regarding intervention frequency(i.e.,number of sessions per week),7 reviews(12%)13,14,16,18,42,67,70included interventions requiring participants to exercise up to 3 times a week,12(21%)15,19,20,30,32,33,35,36,41,44,58,60up to 5 times a week,and 23 (41%)17,24,26,28,29,31,38,39,43,46,48,56,57,59,61,64-66,69,71-74more than 5 times a week.This information was omitted in 12(21%)reviews.21-23,25,27,40,45,47,62,63,68,75

The interventions were either wholly based on physical exercise(n=43;77%)13-21,24,26,28-36,39-43,46,48,57,58,60-63,66-75or had several components(one of which was exercise)(n=11;20%).22,23,25,27,38,47,56,59,64,65,71A total of 9 reviews(16%)22,23,25,27,42,45,47,56,70did not specify the type of physical exercise.A total of 31 reviews(55%)did provide details on physical exercise,which included strength,power,and resistance training (e.g., weights, Theraband);14-17,20,21,26,28,32-39,41,44,46,48,57-61,64-6924 (43%)included endurance(i.e.,cardio fitness,aerobics,dancing,cycling);14,15,28-30,32-34,37-39,44,46,57,60,61,64-66,68,69,72-7417(30%)included meditative movement(i.e.,Tai Chi,Qigong,yoga), mind-body exercises, and psychomotor exercises;15,24,26,33,38-40,43,44,46,57,58,60,63,65,68,7218 (32%)included balance and coordination (e.g., gait training);14,15,21,26,28,33,34,38,39,41,62-65,72-7511(20%)included walking or mobility;14,36,37,41,44,63-65,72,73,7510(18%)included f l exibility and stretching;14,15,34,38,39,64,65,72-747(12%)included ADLs plus functional exercise;37-39,48,63,64,726(11%)included whole-body vibration;13,16,19,31,39,654(7%)included physiotherapy and physical rehabilitation;14,36,56,593(5%)included occupational and recreational therapy;56,59,651(2%)included agility training;33and 4 (7%)included other typesof training(i.e.,face training,exercise-based active videogames,aquatics,chair-based exercises,and calisthenics).18,44,65,71A total of 25 reviews(45%)focused on multiple exercise interventions.14-16,21,23,25-30,32-34,36-41,44,48,56,58-61,63-66,68,69,72,75

Table 4 Characteristics of exercise interventions.

Table 4 (Continued)

Table 4 (Continued)

Table 4 (Continued)

3.5.Objective 2:outcome parameters improved through exercise

3.5.1.Physical functioning,physical health,and physical exercise

Most reviews reported improvements in muscle strength.15-19,34-39,56,65,66,69,70,73 In healthy older adults,improved strength of the lower limbs was reported following progressive resistance training and multimodal exercises,the former producing larger sized effects(standard mean deviation(SMD)=0.33)than the latter(SMD=0.16).34Resistance training was also found to significantly increase lower-(SMD=0.63;p<0.05)and upper-extremity muscle strength(SMD=1.18;p<0.05).35Small but significant effects(p<0.01)on handgrip strength were found in 1 review(SMD=0.28;p<0.05).65Supervision by clinicians during resistance training produced statistically significant effect sizes in improving overall muscle strength(SMD=0.51;p<0.04).15Speci fically,10-29 additional supervised sessions produced the largest improvements(SMD=1.12;p<0.05).15

Nutritional supplementation plus exercise were linked to greater improvements in limb strength compared to exercise alone(SMD=0.33;p<0.05.)36Muscle strength of the lower limbs was significantly improved when healthy older adults received vitamin D3 alongside supervised progressive exercise,compared to exercise orvitamin D3 separately(SMD=0.98;p<0.01).16Protein supplementation plus resistance training produced greater leg-strength gains than physical exercise alone(SMD=0.69;p<0.01).17One review found significant effects of exercise plus protein supplementation in older adults with sarcopenia and risk of frailty on handgrip(SMD=0.44;p<0.01)and leg strength(SMD=0.65;p<0.01).66Greater improvements in the combined exerciseand-protein-supplementation group were found among older adults with body mass indexes above 30(SMD=0.87;p>0.05).17Exercise also significantly improved muscle strength in people with cognitive impairment and dementia,following a walking and mobility training intervention(Hedge’sg=0.75;p<0.01).37It was found that in cardiac patients,a higher volume of exercise yielded a significantly positive effecton functionalrecovery (mean deviation(MD)=27;p<0.01)and a trend toward improvement in cardiopulmonary capacity(MD=0.72;p>0.07).69

In relation to balance,it was found that multimodal exercise significantly improved dynamic standing balance in healthy individuals(SMD=0.46;p<0.01).34Exercise-based active video games produced larger effect sizes than conventional exercise in Berg Balance scores(MD=4.33;p<0.05).18The positive effects of exercise extended to less physically able participants.Whole-body vibration was found to bene fit dynamic balance in participants with physical limitations(SMD=-0.15;p<0.05)and in those in need of care(SMD=-0.90;p<0.05).19Supervision during exercise led to larger improvements in static steady-state balance(SMD=0.28;p< 0.01),dynamicsteady-statebalance(SMD=0.35;p>0.05),proactive balance(SMD=0.24;p>0.05),and balance test batteries(SMD=0.53;p<0.05).15

The reviews reported consistent improvements in gait speed following exercise.Multimodal exercise improved maximal(SMD=0.31;p<0.05)and habitual gait speed(SMD=0.50;p<0.01).34Positive effects in both normal(MD=0.06;p<0.01)and fast gait speed(MD=0.08;p<0.01)were also reported.39Two reviews investigated improvements in the Short Physical Performance Battery.16,39Improvement in the test scores was reported following a combination of different exercise modalities(MD=1.87;p<0.01)39and through physical exercise and vitamin D(SMD=1.09;p>0.05).16Improvement in the sit-to-stand test was reported in 2 reviews.18,34These reviews found that the sit-to-stand test was significantly improved as a result of multimodal exercises(SMD=0.26;p<0.05)and exercise-based video games(MD=3.99;p<0.05).Results in the Timed Up&Go(TUG)test were less consistent.Although it was found that resistance exercise using elastic bands significantly increased TUG times(MD=2.39;p< 0.01),20progressive resistance training(SMD=-0.02) or multimodal exercise interventions(SMD=-0.41;p>0.05)had no significant effects on TUG times.34

Two reviews investigated the long-term outcomes of exercise.70,73One study found that the exercise interventions improved exercise time in participants immediately postintervention(SMD=0.18;p<0.05)and at the 6-month follow-up(SMD=0.30;p<0.05).70However,long-term effects at the 1-year follow-up(SMD=0.27;p>0.05)and 2-year follow-up(SMD=0.03;p>0.05)were lost.70Another review found that older patients recently discharged from hospital walked an average of 23 m more than controls in the 3 months following delivery of rehabilitation exercises(p>0.05).73

3.5.2.Falls-related outcomes,injuries,and mortality

Several reviews investigated number of falls.14,21-27,34,40-42,47,57,60,63,72Participation in exercise interventions resulted in falls reduction in noninstitutionalised(OR=0.78;p< 0.01)and institutionalised participants(OR=0.80;p<0.01).22,40Sherrington calculated,based on a risk of 850 falls in 1000 people followed over 1 year(data obtained from 59 studies included in the meta-analysis),that participants in exercise interventions experienced 195 fewer falls than controls.72

Multimodal exercise showed a particularly positive effect on reducing falls.In home-based muscle strengthening and balance-retraining interventions delivered by therapists,the overall reduction of falls was 35%(IRR=0.65;p<0.05).21A reduced falls rate resulted from multimodal exercise interventions in olderadults with reduced physicalcapacity(RR=0.63;p<0.05)34and in participants with cognitive impairment(RaR=0.68;p< 0.01)34and dementia(MD=-1.06;p<0.01).41,42

The association between delivery setting and number of falls was investigated in 1 review,47which reported that home interventions did not significantly reduce the falls rate(rate ratio(RaR)=1.27;p>0.05).Large effects sizes in falls reduction were instead obtained through integrating physical exercise with falls-reduction strategies,such as home visits and environment modi fication(OR=0.75;p<0.05)40or risk modi fication(mean weighted effect size(MWES)=0.06;p<0.01)and comprehensive risk assessment(MWES=0.12;p<0.01).22Interventions combining exercise and education(OR=0.65)were more effective than those combining exercise and hazard assessment or hazard modi fication(OR=0.66).23

The bene fits of exercise on falls rate extended beyond the active intervention period.Finnegan found significant lasting effects of exercise at a 12-month follow-up(RaR=0.79;p<0.01).63A significant reduction in falls at 12 months was also reported in another review(MWES=0.09;p<0.01).22

The risk of falling following exercise interventions was explored in 4 reviews.24,25,34,41Strength,mobility,and balance exercises delivered in group-based interventions reduced the risk of falling by 32%(RR=0.68;p<0.01).41A 21%protective effect against risk of falls resulted from a multimodal exercise intervention.14One review that looked at the effectiveness of Tai Chi in healthy older adults found a significantly reduced pooled estimated odds ratio for falls.24The effect declined 6 months after the end of the active intervention.25

Two reviews investigated fear of falling.25,26significantly reduced fear resulted from exercise alone(MWES=0.02;p<0.05),a combination of physical exercise and education(MWES=0.24;p<0.05),interventions delivered in the community(MWES=0.22;p<0.05)and in participants’homes(MWES=0.41;p<0.05).25This review found that fear of fallingdecreased at4-month follow-up (MWES=0.24;p<0.05),25but another review26found that the positive effects were not statistically significant at a 6-month follow-up(SMD=0.17;p>0.05).The same review26found no significant effect on fear of falling based on type of exercise,exercise frequency,duration of intervention,or falls risk status of participants,but it did find a significant effect of group(SMD=0.49;p<0.05)over individual delivery(SMD=0.14;p>0.05).

Eight reviews21,27,42,47,57,60,73,75looked at injuries resulting from falls,hopitalization resulting from falls,and mortality resulting from falls.One review found that muscle strengthening and balance exercises reduced the number of participants suffering injuries from falls(IRR=0.65;p<0.05)or being admitted to hospital because of a fall(OR=0.52;p<0.05).21Another review con firmed that exercise significantly decreased the risk of injurious falls(RR=0.74;p<0.05)and resulting fractures(RR=0.84;p<0.05).77Exercise was also linked to a reduction in injurious falls when combined with vision assessment or treatment(OR=0.17;p<0.05)or with environmental assessment or modi fication(OR=0.30;p<0.05).27In 2 other reviews,however,the rate ratio for fractures related to falls did not change significantly with exercise(RaR=1.47;p>0.05),42and exercise delivered at home did not significantly reduce the falls injury rate(RaR=1.16;p>0.05).47In 2 reviews,exercise was reported not to have a significant effect on mortality(RR=0.93;p>0.05 and RR=0.96;p>0.05).57,60

3.5.3.Independence in activities of daily living,quality of life,quality of sleep,and functioning in society

Several reviews investigated independence in ADLs.34,59,64,74A nonsignificant(p>0.05)effect of progressive resistance(SMD=0.13)or multimodal exercise programs(SMD=0.37)on ADLs was reported among older adults with reduced physical capacity.34However,exercise improved independence in ADLs among older adults in residential care(SMD=0.24;p<0.01)59and among community-dwelling frail older adults(SMD=0.54;p<0.01).74

Quality of life was the primary outcome in 4 reviews.13,43,57,74Exercise programs did not produce significanteffectson quality oflifein healthy participants(RaR=0.04;p>0.05)57or frail individuals(weighted mean difference=-0.18;p>0.05),32(MD=0.10;p>0.05),74except for whole-body vibration,in measures including social function(SMD=0.73;p<0.01)and vitality(SMD=0.78;p<0.01).13

Meditative movement interventions produced larger effects on quality of sleep than did sleep therapy or usual care(SMD=-0.70;p<0.01),regardless of the type and duration of the intervention.43The impact of exercise on participation in society(i.e.,individual functioning at the societal level)was investigated in 1 review.28The authors found that multicomponent interventions with an exercise component produced larger effects than exercise alone,although the difference was not statistically significant(SMD=0.22;p>0.05).28

3.5.4.Brain functioning

Brain functioning wasthe primary outcome in 10 reviews.29,30,44,45,57,58,61,67,69,71In healthy older adults,it was found that Tai Chi and aerobic exercises did not reduce the risk of cognitive impairment(RR=1.12;p>0.05)or decline(RR=0.90;p>0.05),but it reduced the risk of dementia(RR=0.57;p>0.05),though not significantly.29It was also found that seated exercise had a significantly positive effect on cognition(SMD=1.20;p<0.01).71Another review67found that a single aerobic/strength exercise bout was able to increase peripheral blood brain-derived neurotrophic factor concentrations(SMD=2.21;p<0.05)and that an exercise program comprising aerobic/strength training increased these concentrations significantly(SMD=4.72;p<0.01).The effectiveness of resistance and aerobic exercise on cognition(Hedge’sg=0.24;p<0.01)was reported in another review.61Garcia-Hermoso et al.57found improvements in healthy adults’cognition following involvement in long-term(i.e.,more than 12 months)interventions(RR=0.24;p<0.01).

In regard to the effects of exercise on cognitive functioning in people with cognitive impairment or dementia,1 review found significant effects on verbal fluency(mean deviation(MD)=1.32;p<0.01)and nonsignificant effects on cognitive f l exibility(MD=6.76;p> 0.05)and delayed memory(MD=-0.01;p>0.05).44Another review found no effects on overall cognition(MWES=0.21;p>0.05)but a significant effect on executive attention (MWES=0.15;p<0.05).30Greater effects were generated when exercise was delivered in group sessions(MWES=0.12;p<0.01)45and in sessions with short durations and high frequencies(d=0.43-0.50),58but no significant effects resulted from different intervention characteristics, such as length(MWES=0.00;p>0.05)and frequency(MWES=0.12;p>0.05).45When comparing physical exercise intervention to computerised cognitive training,music therapy,and nutrition therapy,the former produced the largest improvement in cognition(SMD=0.35;p<0.05).45

3.5.5.Musculoskeletal health,bone density,and muscle mass

Musculoskeletal health was explored in 3 reviews.16,31,66It was found that whole-body vibration had no significant postintervention effects on total(MD=0.00;p>0.05)and femoral neck(MD=0.01;p>0.05)bone mineral density(BMD)in postmenopausal women,but improvements in BMD of the lumbar spine(MD=0.02;p<0.05)31were found.

In comparison to participants who did not receive the intervention,the same review did not find significant improvements in BMD among participants who did receive the intervention in total(MD=-0.01;p>0.05),femoral neck(MD=0.02;p>0.05),and lumbar spine BMD(MD=0.02;p>0.05).31When dividing participants by age group,the authors found no significant differences in BMD of the femoral neck in women younger than 65 years of age pre-and post-intervention(MD=0.02;p>0.05),but they did find a significant difference in BMD of the lumbar spine(MD=0.01;p<0.05).31

A review comparing exercise-onlyvs.multimodal interventions in older adults identi fied statistically significantly larger improvements for BMD of the femoral neck in the combined interventions(SMD=0.02;p>0.05).16

A review focusing on older adults with sarcopenia and frailty risk found that muscle-strengthening exercise and protein supplementation produced significant improvements in the whole-body lean mass(SMD=0.66;p<0.01)and appendicular lean mass(SMD=0.35;p<0.01).66

3.5.6.Mood

Three reviews focused on the effect of exercise on mood.32,46,68significant mood improvement resulted from cardiovascular and resistance training in healthy older adults(SD=0.38;p<0.05).32The effect size was larger for physically active(SD=0.27;p<0.05)compared to physically inactive(SD=0.19;p<0.05)participants.Two reviews tested the effect of different interventions in reducing depression.46,68Heinzel et al.46found that,compared to control conditions at post-treatment,there was a significant reduction in depression following aerobic exercise(SMD=-0.64;p<0.05),resistance training(SMD=-0.76;p<0.05),and alternative exercise(i.e.,Tai Chi,Qigong,dancing)(SMD=-0.97;p<0.05).When differentiating by intervention characteristics,the authors identi fied a significant effect size for supervised training(SMD=-0.77;p<0.05).46Miller et al.68found that the largest improvement in depressive symptoms resulted from mind-body exercise(Hedge’sg=-0.87 to-1.38),followed by aerobic exercise(Hedge’sg=-0.51 to-1.02)and resistance exercise(Hedge’sg=-0.41 to-0.92).

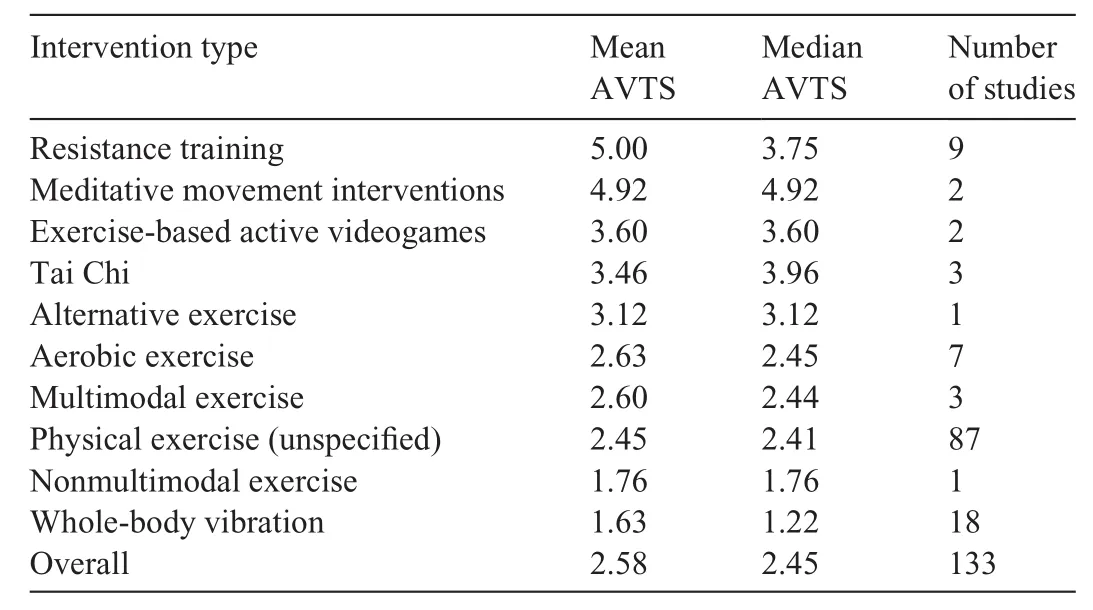

Table 5 Ranking of interventions,based on aggregated effect sizes.

3.6.Objective 3:ranking of interventions based on aggregated effect sizes

Table 5 ranks interventions based on their aggregated effect sizes,from largest to smallest improvements.In brief,the largest effect sizes were found for interventions based on resistance training.The smallest effect sizes were found for whole-body vibration interventions.

4.Discussion

This systematic review of meta-analyses synthesized the evidence concerning exercise interventions in older adults in order to characterise the extent of the diversity and inconsistency of the literature in this area.We also aimed to identify gaps in the literature in order to suggest future directions in research.

Overall,our review found that resistance training supported by nutritionalsupplementation significantly improved muscle strength,whereas multimodal exercises and whole-body vibration,particularly if supervised,produced significant balance improvements.Resistance training and multimodal exercises may improve general physical performance measures.The evidence for exercise interventions in reducing falls and fear of falling was inconsistent.The effect may depend on the place where the individual lives,whether the individual was part of a clinical group,the setting of the intervention,and the integration of additional strategies into the intervention,such as home modi fications and nutritional supplementation.It was found,however,that multimodal exercise interventions reduced the riskof falling.The evidence regarding exercise in reducing falls-related injuries was inconsistent,and the effectiveness of interventions may depend on additional intervention components,such as environmental or visual assessments.Overall,our review showed that quality of life may be improved through some forms of exercise(wholebody vibration)and in some groups(healthy older adults)but not in others(people with frailty).Regular meditative movement exercise may be bene ficial for quality of sleep.The evidence regarding exercise for improving cognitive function and preventing cognitive impairment was inconsistent,but physical exercise may be more effective than music,nutritional therapies,or cognitive training.

Our work is characterised by certain strengths and limitations.In relation to limitations at the level of the individual meta-analyses,most meta-analyses included multicomponent(e.g.,resistance and endurance training)interventions and did not report results separately for individual components,making it dif ficult to associate exercise type with effect sizes.In some instances,there was no description of the type of exercise investigated in the meta-analysis and was referred to only as “exercise”.The meta-analyses were also extremely heterogeneous in the target populations,number of studies,number of participants included in the studies,and primary outcomes.

There were also limitations pertaining to this review.Each meta-analysis was appraised for quality by 1 rater only,which might have caused single-rater bias.There are also limitations inherent in the use of the CASP.For example,the CASP does not attribute a score to reporting of sample size,which is key information required for power calculation of intervention effectiveness.Despite the lack of this information,2 meta-analyses still scored 8 and 9 on the CASP.Therefore,we urge caution in interpreting the results of our quality appraisals because they re flect the quality of the meta-analyses only in relation to the speci fic aspects included in the CASP.Also,given the diversity of the studies included in our review,it was impossible to meta-analyze data.Although we were not able to synthesize a pooled estimate from all the studies,we generated a comparison metric(AVTS)for each study and then grouped the studies based on type by using means and medians.This gave us an indication of which study types appeared to generate the strongest or weakest effect sizes.However,caution is needed when drawing conclusions from our findings,given that we combined very different interventions and that the AVTS metric is based,in many instances,on data aggregated from a limited number of reviews.Nonetheless,the aggregated metrics represent essential groundwork,which can inform future literature reviews with a narrower scope.For example,given the potential largest effect of resistance training,future research could explore whether the effects of this type of exercise also extend to “nonclinical”outcomes,such as changes in physical activity behavior(i.e.,increased engagement of participants in exercise following delivery of resistance training interventions).This is particularly relevant,considering that,in order to achieve maximum bene fits,adherence to exercise is crucial76but that research has evidenced poor adherence to exercise among older adults.77-79

The AVTS suggests that studies delivering resistance training show the largest improvements.This is in line with previous research,adding to the evidence that resistance training is bene ficial for musculoskeletal health,promotes the maintenance of functional abilities,and protects from osteoporosis,sarcopenia,and lower-back pain.80There is also mounting evidence of the protective effect of resistance training against health conditions typically associated with aging,including diabetes,heart disease,and cancer.80Research has found that a positive impact on insulin resistance,resting metabolic rate,glucose metabolism,blood pressure,body fat,and gastrointestinal transit time can be obtained even through two 20-min resistance-training sessions a week.80

In relation to the other types of interventions,Tai Chi and meditative movements exercise studies reported larger effect sizes that those delivering purely physical types of exercise such as aerobics,though it must be recognized that the AVTS for these studies was based on fewer reviews.It might be that less physically intensive types of exercises are more suitable to an aging population,thus generating more improvements.

The promising results of exercise-based videogames emerging from the AVTS re flect the growing evidence of the bene fits of assisting technology(AT)in improving the lives of older adults.AT is de fined as“any device or system that allows an individual to perform a task that they would otherwise be unable to do,or increases the ease and safety with which the task can be performed”,81and its contribution to older people’s independence and autonomy has been evidenced in a number of studies.Despite the promising results,however,there is contradictory evidence concerning older people’s acceptance of AT.82,83Acceptability,in the context of physical exercise for older people,where low levels of engagement in the prescribed programs are common,84is a crucial aspect for ensuring adherence to an exercise regime and,thus,to an intervention’s effectiveness.

The AVTS revealed that larger effect sizes were obtained through multimodal interventions(e.g.,resistance and cognitive training)as opposed to nonmultimodal formats.This is in line with previous evidence concerning the bene fits of multimodal exercises,such as dual-tasking(i.e.,undertaking a physical and cognitive task simultaneously),85resulting in a growing popularity of exercise programs featuring multimodal interventions forpeople with dementia and cognitive impairment.86It was also found that integration of physical exercise with preventive or educational initiatives(e.g.,falls education)was associated with larger effect sizes than for exercise programs without such initiatives.This finding echoes recent theoretical developments in behavior-change theories and points to the crucial role of information and education about physical exercise(and its bene fits)in efforts to boost motivation for initiating and adhering to exercise programs.87

This review also evidenced important gaps in research that need to be addressed.Our review of studies of group exercises suggests that this delivery format yields effect sizes similar to those that individual exercises yield,on several outcomes.There might be added value to group delivery that goes beyond the physical bene fits.For example,group activities may promote social integration and maintenance of a social identity role,particularly among individuals who are at risk of social exclusion,such as older people living in rural areas88and those with dementia.89The motivational argument also seems to validate group delivery.Participants in group interventions can encourage each other and boost intrinsic motivation to engage in physical exercise.90In the context of a group program,there is also the potential for information sharing among participants.Given the inconsistency of the evidence about group exercises,however,it is crucial to generate further evidence in order to examine the potential of this format.

Few of the meta-analyses we reviewed reported long-term adherence to exercise or its impact after the intervention period had finished.In the few instances where adherence to and bene fits of interventions were investigated longitudinally,the results were inconsistent.It would be useful,therefore,to explore the long-term effects of interventions,which can go beyond the mere physical bene fits and strategies for how best to obtain them.Research has found,for example,that the input of professionals’delivering exercise interventions might represent a resource for long-term engagement in physical activity because these professionals can provide information about services and support networks available in the community which,in turn,might help older people maintain physical activity levels91and gain long-term bene fits.

Physical health outcomes were the primary focus of 80%of the reviews,whereas psycho-socio-emotional variables(e.g.,mood and affect,quality of life,independence)amounted only to roughly 20%.It was also surprising to note that only 1 multimodal intervention64featured motivational strategies.Given the relevance of motivation in mediating adherence to exercise interventions(and,in turn,their effect on physical outcomes),84,92further research in this area is needed.

Interestingly,none of the interventions focused on the role of significant others(e.g.,family,friends,and caregivers)in contributing to improved outcomes.In the context of physically or cognitively impaired individuals in particular,carers might become key agents in intervention success.93It is,therefore,pivotal to conduct research in this area.None of the reviews investigated or described which characteristics of professionals or which dynamics in the professional-client rapport were associated with greatest effect sizes.Previous literature indicates that the technical knowledge and skills of trained professionals ensure optimal adherence to exercise.91The motivational support provided by professionals can also be instrumental for higher uptake and,in turn,greater improvements in intervention outcomes.Further research,therefore,is also needed in this respect.

5.Conclusion

This review found that exercise interventions for older adults are extremely diverse and that the findings from the included studies were mostly inconsistent.We were able to aggregate some of the effect sizes reported in the meta-analyses,which seem to suggest that the most effective interventions were resistance training,meditative movement interventions,and exercise-based active videogames.We advocate for further,more focused review work in order to con firm the trends we have identi fied in our review.Our review also identi fies important gaps in research,including a lack of studies investigating the bene fits of group interventions,the characteristics of professionals’delivering the interventions associated with better outcomes,the impact of motivational strategies on intervention outcomes,and the impact of significant others(e.g.,carers)on intervention delivery.

Acknowledgment

This work was funded by the National Institute for Health Research(NIHR)under its Programme Grants for Applied Research Programme(ReferenceNumberRP-PG-0614-20007).The views expressed are those of the author(s)and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Authors’contributions

CDL developed the protocol of this manuscript,ran the database searches,selected the included meta-analyses,appraised their quality,extracted data,developed and revised the manuscript;AL developed the protocol of this manuscript,ran the database searches,selected the included meta-analyses,and appraised their quality;AdB ran the statistical analyses;RHH contributed to the development of the protocol and revised the manuscript;JRFG,SS,PL,and AB revised the manuscript;VvdW developed the protocol of this manuscript,ran the database searches,selected the included meta-analyses,appraised their quality,and revised the manuscript.All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript,and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2020.06.003.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2021年1期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2021年1期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Author biographies of Editor-in-Chief’s choice

- Association between physical activity and digestive-system cancer:An updated systematic review and meta-analysisT

- Risk factors for overuse injuries in short-and long-distance running:A systematic reviewT

- Physical exercise may exert its therapeutic in fluence on Alzheimer’s disease through the reversal of mitochondrial dysfunction via SIRT1-FOXO1/3-PINK1-Parkin-mediated mitophagyT

- he mirror’s curse:Weight perceptions mediate the link between physical activity and life satisfaction among 727,865 teens in 44 countriesT

- Sensor-based physical activity,sedentary time,and reported cell phone screen time:A hierarchy of correlates in youthT