Association between physical activity and digestive-system cancer:An updated systematic review and meta-analysisT

Fngfng Xie,Ynli You,Jihn Hung,Chong Gun,Ziji Chen,Min Fng,Fei Yo,*,Ji Hn*T

aSchool of Acupuncture-Moxibustion and Tuina,Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine,Shanghai 201203,China

bDepartment of Traditional Chinese Medicine,Changhai Hospital,Naval Medical University,Shanghai 200433,China

cCenter for Drug Clinical Research,Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine,Shanghai 201203,China

dDepartment of Physiotherapy and Sport Rehabilitation,Shanghai University of Sport,Shanghai 200438,China T

Received 13 December 2019;revised 22 April 2020;accepted 17 July 2020 Available online 30 September 2020

2095-2546/©2021 Published by Elsevier B.V.on behalf of Shanghai University of Sport.This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

Abstract Background:Physical activity(PA)may have an impact on digestive-system cancer(DSC)by improving insulin sensitivity and anticancer immune function and by reducing the exposure of the digestive tract to carcinogens by stimulating gastrointestinal motility,thus reducing transit time.The current study aimed to determine the effect of PA on different types of DSC via a systematic review and meta-analysis.Methods:In accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses(PRISMA)guidelines,we searched for relevant studies in PubMed,Embase,Web of Science,Cochrane Library,and China National Knowledge Infrastructure.Using a random effects model,the relationship between PA and different types of DSC was analyzed.Results:The data used for meta-analysis were derived from 161 risk estimates in 47 studies involving 5,797,768 participants and 55,162 cases.We assessed the pooled associations between high vs.low PA levels and the risk of DSC(risk ratio(RR)=0.82,95%con fidence interval(95%CI):0.79-0.85),colon cancer(RR=0.81,95%CI:0.76-0.87),rectal cancer(RR=0.88,95%CI:0.80-0.98),colorectal cancer(RR=0.77,95%CI:0.69-0.85),gallbladder cancer(RR=0.79,95%CI:0.64-0.98),gastric cancer(RR=0.83,95%CI:0.76-0.91),liver cancer(RR=0.73,0.60-0.89),oropharyngeal cancer(RR=0.79,95%CI:0.72-0.87),and pancreatic cancer(RR=0.85,95%CI:0.78-0.93).The findings were comparable between case-control studies(RR=0.73,95%CI:0.68-0.78)and prospective cohort studies(RR=0.88,95%CI:0.80-0.91).The meta-analysis of 9studies reporting low,moderate,and high PA levels,with 17 risk estimates,showed that compared to low PA,moderate PA may also reduce the risk of DSC(RR=0.89,95%CI:0.80-1.00),while compared to moderate PA,high PA seemed to slightly increase the risk of DSC,although the results were not statistically significant(RR=1.11,95%CI:0.94-1.32).In addition,limited evidence from 5 studies suggested that meeting the international PA guidelines might not significantly reduce the risk of DSC(RR=0.96,95%CI:0.91-1.02).Conclusion:Compared to previous research,this systematic review has provided more comprehensive information about the inverse relationship between PA and DSC risk.The updated evidence from the current meta-analysis indicates that a moderate-to-high PA level is a common protective factor that can significantly lower the overall risk of DSC.However,the reduction rate for speci fic cancers may vary.In addition,limited evidence suggests that meeting the international PA guidelines might not significantly reduce the risk of DSC.Thus,future studies must be conducted to determine the optimal dosage,frequency,intensity,and duration of PA required to reduce DSC risk effectively.

Keywords:Digestive-system cancer;Meta-analysis;Physical activity

1.Introduction

Digestive-system cancer(DSC)includes cancers of the digestive tract(mouth,throat,oesophagus,stomach,small intestine,and colorectum)and the digestive accessory organs(pancreas,gallbladder,and liver).1,2DSC,which is considered a worldwide health problem,is the leading cause of cancerrelated deaths worldwide.3In 2018,approximately 319,160 new cases and 160,820 DSC-related deaths were recorded in the United States.4In the past 20 years,colon,rectal,stomach,and liver cancers were among the top 10 leading cancers worldwide,and colorectal,liver,and stomach cancers accounted for920,000,577,000,and 535,000 deaths,respectively.5In addition,the 5-year survival rate of patients with DSC is less than 20%.6The high prevalence and risk of death and poor prognosis underscore the need to identify possible measures in primary care that can prevent DSC.7

Research data have shown that healthy lifestyle habits,7such as proper diet,8,9smoking cessation,10,11decrease in body mass index,12,13alcohol avoidance,14prevention of obesity,15,16and increased physical activity(PA),may reduce the risk of DSC.A significant body of evidence has revealed that PA plays a crucial role in maintaining and enhancing health status,particularly because the global epidemic of sedentary lifestyle is increasing.Moreover,good lifestyle habits have been found to be an extremely effective and affordable method for preventing and treating several noncommunicable chronic diseases.17In addition,5 years ago,World Health Organization reports showed a 7%decrease in overall cancer risk,with DSC having the highest rate of reduction.18The protective effect of PA against cancer may be mediated by decreasing systemic in flammation, thereby leading to favorable immunomodulation.19

In the past decade,a series of epidemiological studies20-66has investigated the relationship between PA and the risk of DSC,including colon cancer,23,24,26,28-30,37,41,43,47,52,54,56-58,63rectal cancer,21,23-26,31,32,34,43,46,52,61colorectal cancer,22,23,34,36,37,39,46,49,52,53,59,63,64,67oesophageal cancer,21,24,35,42,45,50,59,65gallbladder cancer,27,65gastric cancer,21,38,44,45,47,50,59,60,65oropharyngeal cancer,24,31,51,55,65liver cancer,24,27,47,65and pancreatic cancer.24-26,32,33,40,47-49,55,59,64-66

Some studies have shown that PA may reduce the risk of certain types of digestive cancer,such as oesophagea,1gastric,21colorectal,22and liver cancer.23However,systematic reviews of DSC cancer were conducted 5 years ago,24-26and in that review,data on some DSCs,such as gallbladder,oral cavity,and pharyngeal cancers were missing.Since that time,a comprehensive study that provides more complete information of the effect of PA on the risk of DSC has not been undertaken.Therefore,we performed a comprehensive meta-analysis of multiple studies27-72in order to provide and quantify updated data on the relationship between PA and DSC risk.

2.Materials and methods

The protocol for our review is available at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD420181 04367.

2.1.Literature search

A meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses(PRISMA)guidelines.73To quantify the association between PA and the risk of DSC,2 authors(FX and JH)independently searched for studies published between January 2008 and November 2018 that were cited in PubMed,Embase,Web of Science,Cochrane Library,and China National Knowledge Infrastructure.In case of disagreement between the 2 authors,a final consensus was reached via team discussion.

Studies were retrieved using medical subject headings combined with entry terms.We used the following terms for PA:“PA”, “Exercises”, “Activities,Physical”, “Activity,Physical”,“Physical Activities”,“Exercise,Physical”,“Exercises,Physical”,“Physical Exercise”,“Physical Exercises”,“Acute Exercise”,“Acute Exercises”,“Exercise,Acute”,“Exercises,Acute”, “Exercise, Isometric”, “Exercises, Isometric”,“Isometric Exercises”,“Isometric Exercise”,“Exercise,Aerobic”, “Aerobic Exercise”, “Aerobic Exercises”, “Exercises,Aerobic”, “Exercise Training”, “Exercise Trainings”,“Training,Exercise”,and “Trainings,Exercise”.Subsequently,we used the AND operator to combine these terms with the following termsfor DSC outcomes: “DSC”,“Digestive System Neoplasm”, “Digestive System Neoplasms”,“Neoplasm,Digestive System”,“Neoplasms,DigestiveSystem”, “Cancerof DigestiveSystem”, “DSCs”,“Cancer,Digestive System”,and “Cancers,Digestive System”.Similarly,we used the AND operator to combine the PA terms with mouth cancer,gastric cancer,pancreatic cancer,gallbladder cancer,liver cancer,oesophageal cancer,small intestine cancer,and colorectal cancer(Supplementary File 1).The search strategy used was based on research articles involving human subjects.An article was considered eligible if the reported relative risk estimate was equivalent to the corresponding 95%con fidence interval(95%CI)or data.Studies on DSC cancer survivors classi fied as reviews,metaanalyses,editorials,letters,practice guides,and news were excluded.

We de fined PA based on the duration,domain,quality,frequency,and category of activities.The duration of activity was used to evaluate the time spent per week in PA.The assessment of energy expenditure was expressed in weekly metabolic equivalent tasks(METs).The quality of PA was based on the following categories:low PA(<600 METs),moderate PA(600-3000 METs),and high PA(>3000 METs).

2.2.Data extraction

To assess the possible differences in the relationship between PA and DSC,we extracted the risk estimates from each included study for each of the DSC subtypes,which allowed all DSC cases to be considered.Speci fically,for each study,we obtained the last name of the first author,year of publication,study location,sample size,case numbers,cancer site,domains of PA,gender,timing of PA,highvs.low,highvs.moderate,and moderatevs.low category of PA,risk estimates(95%CI),and adjusted factors in each study.Gender was considered an independent sample in this study.Thus,the risk estimates for men and women were extracted independently.If a study reported high,moderate,and low domains of PA,data about the estimates of all domains were collected.

Ofthe 47 studies thatmetthe inclusion criteria,seven36,47,53,57,63,64,69reported risk estimates with high PA levels,and they wereconsidered the reference group.Compared with other studies,we converted the relative risk estimates(RRi)to their reciprocal values.The rest of the studies were extracted directly with reference to high PA levels.

2.3.Risk-of-bias assessment

We used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale(NOS)for the assessment of study quality,which was independently evaluated by 2 investigators(FX and JH).If there was a disagreement,the 3rd experienced investigator(FY)joined the discussion until a consensus was reached.The total NOS score was 9,which was suitable for evaluating case-control studies(selection,comparability,and exposure)and cohort studies(selection,comparability,and outcome).Studies with a quality score≤4 were categorized as low-quality studies,and those with a score of≥5 were categorized as high-quality studies.

2.4.Statistical analysis

The hazard ratios and odds ratios were presented as estimates of the RRifor the measurement of the association between PA and DSC risk.When RRiwere available,we used the adjusted risk estimates reported in the original literature.Otherwise,the RRiand 95%CIs were calculated using Stata software(Stata Corp,College Station,TX,USA).The natural logarithms of the risk estimates log(RRi)were calculated on the basis of corresponding standard error(SE):si=(log(upper 95%CI bound of RR)-log(RR))/1.96.A random effects model was used to account for the log(RRi)s,which was weighted by wi=1/(si2+t2)(si=error of log(RRi),t2=population variance).74Q-andI2-statistics were used to assess heterogeneity.74In addition,to examine any publication bias,we used funnel plots,the Begg rank test,75and the Egger regression test.76pwas considered statistically significant at a 0.05 level.In addition,to ensure the authenticity of publication,we performed a sensitivity analysis using the trim-and- fill method,as presented by Duval and Tweedie,77to evaluate any publication bias.

A sub-analysis was conducted to investigate whether the summary risk estimate was affected by cancer site(colon,rectum,colorectum,gallbladder,stomach,liver,pancreas,or oral cavity and pharynx),PA level(high,moderate,or low),international PA guidelines(above or below 150 min/week or 600 METs-min/week or 10 METs-h/week),study design(prospective,case control),gender(men,women),region of the study(North America,Europe,Australia,Asia,or Middle East),PA domain(recreational,occupational),timing for PA(recent,past,or consistent PA),adjustment for smoking(yes,no),body mass index(BMI)(yes,no),and alcohol intake(yes,no).To investigate the impact of prespeci fied potentially in fluential methodological factors on summary risk estimates,a random effects meta-analysis regression was used to analyze all 161 risk estimates.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata software(Version 11.0;Stata).The RRs were reported along with 95%CI.The statistical signi ficance was set at a 0.05 level.

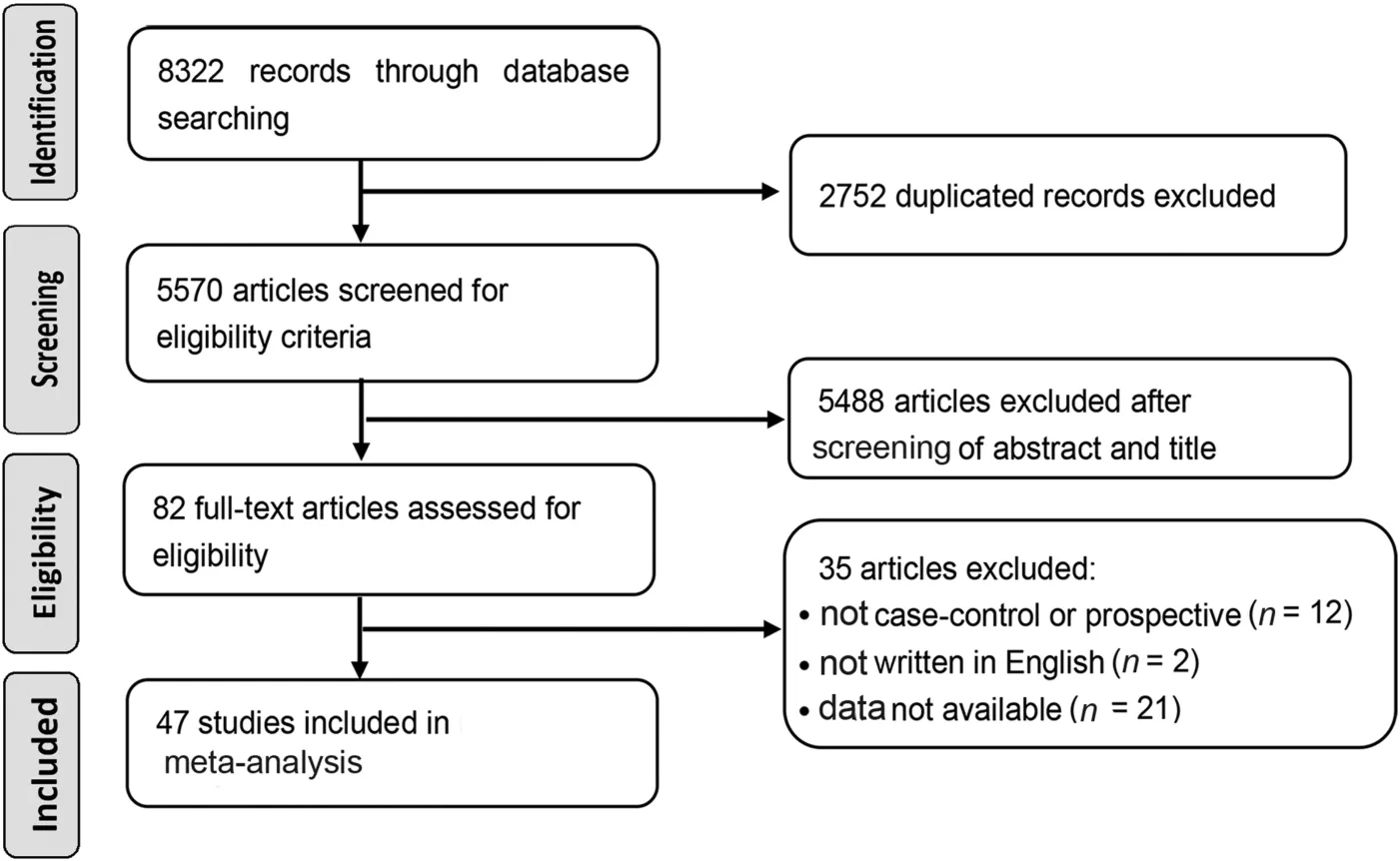

Fig.1.Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses(PRISMA) flow diagram of identi fication and selection of eligible studies.

3.Results

Our initial search identi fied 8322 articles,of which 2752 duplicates were excluded,and 5488 articles were further excluded after browsing the titles and abstracts.The 82 remaining studies were assessed in depth.A total of 47 studies were included in our final analysis(Fig.1).

Supplementary Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the 161 risk factors in 28 prospective studies27,28,31,35-45,47,49-52,55-57,59,61,63,66,68,70and 19 case-control studies29,30,32-34,48,51,53-55,58,60,62,64,65,67,69,71,72that described the association between PA and DSC risk.The studies evaluated 9 cancer sites,including the colon,29,30,32,34-36,43,47,49,53,57,59,62-64,69rectum,27,29-32,37,38,40,49,52,57,67colorectum,28,29,40,42,43,45,52,55,57,58,63,67,68,71oesophagus,30,41,48,51,55,65,71,gallbladder,33,71stomach,27,44,50,51,53,55,65,66,71oropharynx,30,37,56,61,71liver,30,33,53,71and pancreas.30-32,38,39,46,53-55,60,65,70-72This meta-analysis included a total of 5,797,768 participants and 55,162 cases,and 23 studies examined more than 1 DSC endpoint.Moreover,13 studies investigated more than 1 PA domain;11 studies presented results strati fied according to gender.A total of 24 studies assessed recent PA,10 studies collected information about past PA,and 18 studies evaluated consistent PA over time.Smoking status and BMI were adjusted in 33 and 30 studies,respectively.

We summarized 161 risk estimates using the random effects model in 47 studies,and an 18%reduction was observed in DSC risk for those with high PA levels compared to those with low PA levels(RR=0.82,95%CI:0.79-0.85),with moderate between-study heterogeneity(I2=57%,p<0.001 for heterogeneity across all studies),for colon cancer(RR=0.81,95%CI:0.76-0.87),rectalcancer(RR=0.88,95%CI:0.80-0.98), colorectal cancer (RR=0.77, 95%CI:0.69-0.85), gallbladder cancer (RR=0.79, 95%CI:0.64-0.98),gastric cancer(RR=0.83,95%CI:0.76-0.91),liver cancer(RR=0.73,95%CI:0.60-0.89),oropharyngeal cancer(RR=0.79,95%CI:0.72-0.87),and pancreatic cancer(RR=0.85,95%CI:0.78-0.93).No statistically significant association was observed between PA levels and oesophageal cancer(RR=0.84,95%CI:0.66-1.07)(Supplementary Fig.1).Publication bias was considered using the funnel plot(Supplementary Fig.2A),the Begg rank test(p=0.216)(Supplementary Fig.2B),the Egger regression test(p=0.024)(Supplementary Fig.2C),and the trim-and- fillmethod(p<0.001;Supplementary Fig.2D).

We independently analyzed prospective and case-control studies.A statistically significant inverse relationship was found between PA level and DSC in prospective studies(RR=0.88,95%CI:0.80-0.91;I2=42.5%)and case-control studies(RR=0.73,95%CI:0.68-0.78;I2=49.2%).All differences had ap<0.001(Supplementary Fig.3).In terms of genderdifference,thesummary risk estimateofwomen(RR=0.85,95%CI:0.78-0.93,p<0.001)was more likely to be similar to that of men(RR=0.84,95%CI:0.80-0.88,p<0.001)(Supplementary Fig.4).

In terms of the effects of differing levels of PA on the risk of DSC,the meta-analysis of 9 studies27,31,32,40,48,59-61,66reporting low,moderate,and high PA levels,with 17 risk estimates,showed that compared to low PA,moderate PA may also reduce the risk of DSC(RR=0.89,95%CI:0.80-1.00)(Supplementary Fig.5)and that compared to moderate PA,high PA seemed to slightly increase the DSC risk,although the results were not statistically significant(RR=1.11,95%CI:0.94-1.32)(Supplementary Fig.6).In addition,limited evidence from 5 studies30,40,49,58,64suggested that meeting the international PA guidelines might not significantly reduce the risk of DSC(RR=0.96,95%CI:0.91-1.02),with high between-study heterogeneity(I2=99.7%)(Supplementary Fig.7).

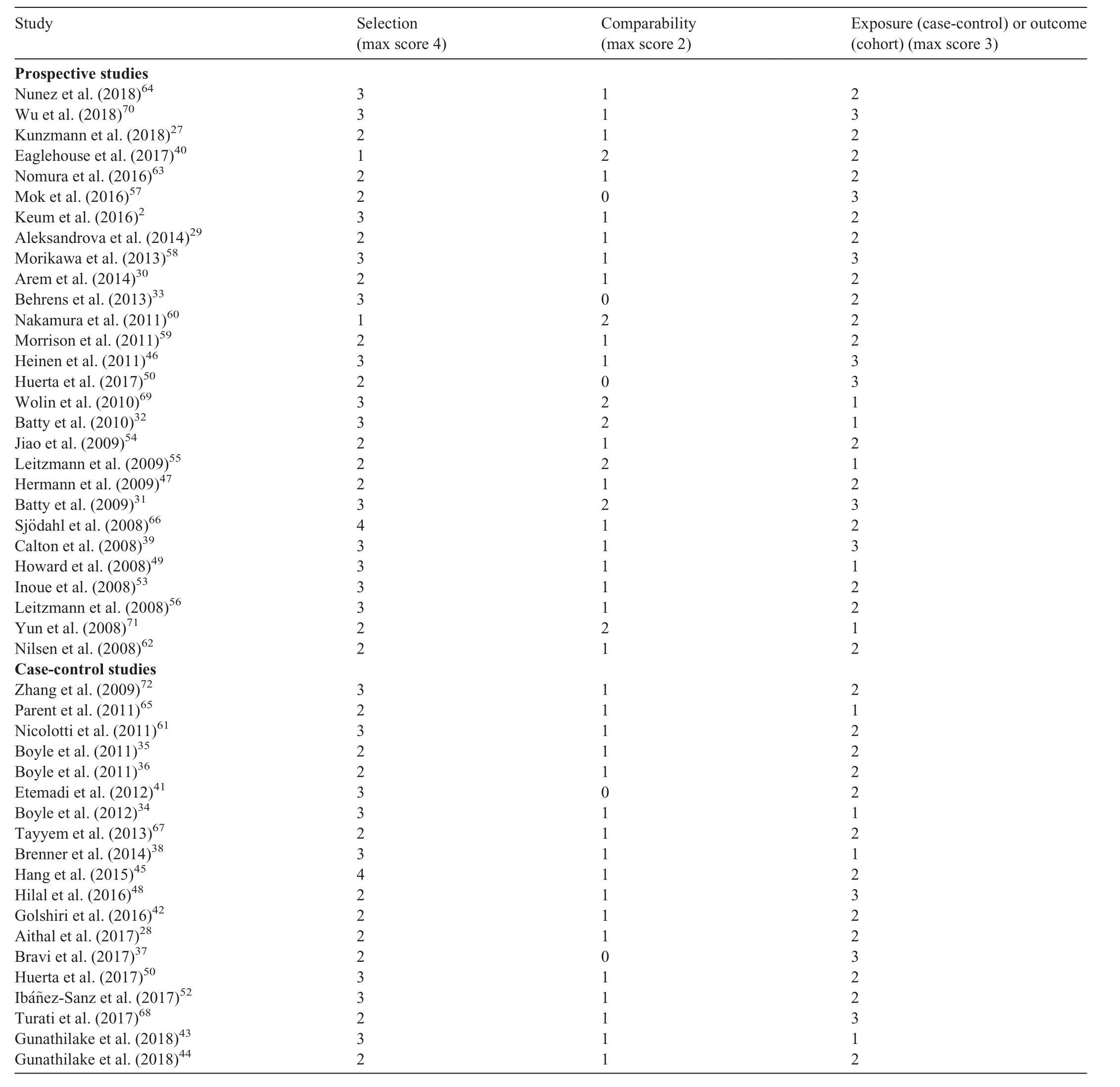

The study quality is shown in Table 1.The average quality score was 5.60(SD=0.83,median=5.00).The included studies had multiple potential confounders,such as smoking(39/47),alcohol drinking(37/47),BMI(30/47),and family histories of DSC(19/47).Most of the studies corrected for the symptoms of DSC.Moreover,18 studies included clear diagnoses and de finitions of DSC,and the overall evaluation score was more than 6,which indicated high quality,according to the questionnaire survey.However,whether the case group was a continuous case and whether it was representative were not discussed.

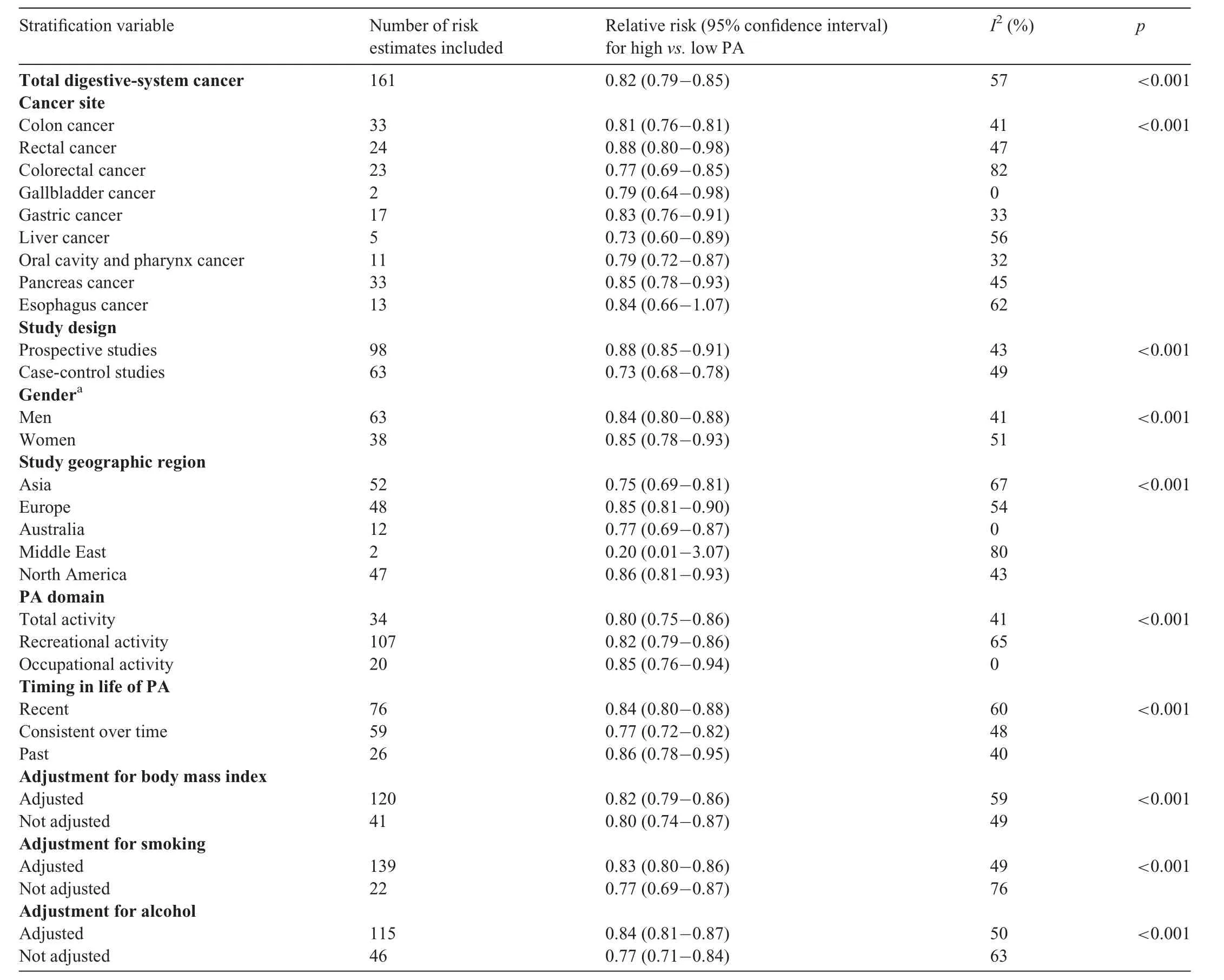

Table 2 presents the characteristics of the included studies that assessed the relationship between DSC risk and differing levels of PA(highvs.low PA level,moderatevs.low PA level,and highvs.moderate PA level).There were 12 studies in Asia,28,40,42-45,53,57,60,67,70,71three in Australia,34,36,64sixteen in Europe,27,29,31,32,37,38,46,47,50-52,59,61,62,66,68one in the Middle East,41and thirteen in North America;30,33,39,48,49,54-56,58,63,65,69,72these yielded a total of 52,12,48,2,and 47 risk estimates,respectively.In the sub-analysisofDSC,previousPA(RR=0.86,95%CI:0.78-0.95;I2=40%),consistent PA over time(RR=0.77,95%CI:0.72-0.82;I2=48%),and recent PA(RR=0.84,95%CI:0.80-0.88;I2=60%)significantly reduced DSC risk.Similarly,the inverse relationship between cancer and activity types in the PA domain was also statistically significant,with variables including total activity(RR=0.80,95%CI:0.75-0.86),recreational activity(RR=0.82,95%CI:0.79-0.86),and occupational activity(RR=0.85,95%CI:0.76-0.94).We pooled the findings from these studies and found a significant difference in terms of the gender,geographic region of the study,BMI,smoking status,and alcohol consumption after adjustment(p<0.001).

4.Discussion

4.1.Association between PA and DSC risk

Because more people want exercise to be included in clinical cancer care,78,79the 2010 American College of Sports Medicine International Multidisciplinary Roundtable recommendations followed the 2008 Guidelines for Physical Activities of Adults with Chronic Illnesses,with a goal of at least 150 min/week of aerobic activity.This exercise recommendation is believed to be safe during and after cancer treatment and can improve some health outcomes.80,81In 2018,the American College of Sports Medicine International Multidisciplinary Roundtable on Physical Activity and Cancer Prevention and Control was tasked with updating the recommendations based on available evidence.One of the key reviews focused on evidence from the exercise method,including aerobic exercise,resistance exercise,and aerobic plus resistance training,as it related to health outcomes.82Thus,our meta-analysis selected exercise patterns based on differing levels of PA(highvs.low PA,moderatevs.low PA,and highvs.moderate PA,as well as on meetingvs.not meeting the international PA guidelines).We examined cancer risk according to cancer site,geographic region,PA intensity,timing of PA,and type of PA assessment.A random effects meta-analysis of the association between PA and DSC was conducted,and our results showed that PA is a protective factor in DSC and that a high PA level was associated with a decrease in DSC risk by 18%,which is consistent with a previous prospective study showing that PA can reduce the risk of DSC by at least 17%.12Speci fically,our results regarding the significant effects of PA on reducing the risk of DSC are consistent with those from previous studies that have investigated the relationship between PA and risk of a single type of DSC,such as colon,83rectal,84colorectal,85gastric,86pancreatic,24and liver cancer.23However,our results showed that the effect of PA on colorectal,85liver,23and pancreatic cancer24yielded a more pronounced risk reduction,whereas there was less risk reduction with increased PA for the other DSCs,such as colon,83gastric,86and oesophageal cancer.26More important,our study is the first to report that PA has an effect on the risk of gallbladder cancer and oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer,with a risk reduction of 21%.

Table 1Quality of studies according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

In addition to the finding that a high PA level was associated with a decrease in DSC risk,our study also assessed the association between different levels of PA and DSC risk.Our results indicated that compared to low PA,moderate PA may also effectively reduce the risk of DSC.However,compared to moderate PA,high PA seemed to slightly increase the DSC risk,although the results were not statistically significant.Some evidence has suggested that high-intensity PA may have a negative effect on the human immune system.87Therefore,intensi fied PA may suppress the immune system’s ability to detect and destroy DSC-related malignant cells.Furthermore,our findings,based on a limited number of studies,suggested that meeting the international PA guidelines might not significantly reduce the risk of DSC.Our finding is inconsistent with other research,where meeting or exceeding PA guidelines was found to be associated with lowered cancer risk.88This may be because the sample size of our included studies was small and between-study heterogeneity was high(I2=99.7%).Therefore,future studies should determine the optimal level of PA required to reduce DSC risk effectively.

In our review,there was strong evidence showing that the association between PA and DSC risk varied according to the study’s design,the gender of the participants,the geographic region in which the study was conducted,the PA intensity,the timing of PA,the type of PA assessment,and the adjustment factors(such as smoking,BMI,and alcohol).The in fluence of these factors was examined in a previous meta-analysis of PA and prostate,89gastric,86and gastroesophageal cancer.20The findings in those studies were similar to ours in that a statistically significant association was found between study design89and gender86as well as PA domain.20In addition,we examined whether smoking,BMI,and alcohol mediated the inverse relationship between PA and risk of DSC by comparing risk estimates that accounted for these factors to those without those factors.Notably,the inverse association between PA and DSC was not attenuated when the meta-analysis was restricted only to datasets adjusted for smoking,BMI,and alcohol consumption,which is in accordance with a previous meta-analysis of PA and pancreatic cancer.24Our results indicate that the biological mechanisms by which PA decreases the risk of DSC are not strictly regulated by smoking,BMI,or alcohol control.

Table 2 Summary risk estimates of high vs.low physical activity(PA),strati fied by selected characteristics.

In our review,the inverse association between PA and DSC was slightly more evident in men than in women,and the treatment of DSC significantly differed in terms of gender.One possible explanation for this finding is that men had higher family communication scores than women,and men were more likely not to talk about their negative symptoms,such as side effects or relapses,during the quantitative phase.90This condition may indicate a relationship between gender and role because negative symptoms can significantly affect the physical status and survival rates of patients.91

4.2.Biological mechanisms

The molecular pathophysiology of DSC implies an in flammatory mechanism,which involves the interaction among various in flammatory cells,immune cells,proin flammatory mediators,cytokines,and chemokines,and this may lead to signaling toward tumor cell proliferation and growth.91The findings in the present study can be explained by some biological mechanisms,such as increased estrogen and testosterone levels,92enhanced anti-oxidant defences,decreased circulating insulin levels,93reduced exposure of the digestive tract to carcinogens,93and increased plasma 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels.94In addition,PA may have an impact on DSC via the proin flammatory pathway,which is mediated by reducing the cyclooxygenase-2 in flammatory response.95-97The exact mechanisms underlying the association between high PA level and reduced DSC risk still have not been fully elucidated.However,PA is believed to improve the number or the function of natural killer cells.97

The consistency of risk reduction in all types of DSC observed in our study indicates that PA is a common protective factor for these cancers.DSCs have common risk factors,even though they have distinct etiologies,and this result is supported by studies showing that some factors,such as smoking 1-10 cigarettes per day over a lifetime,98alcohol intake,99-101excessive food intake,102-104and the use of aspirin/non-steroidal anti-in flammatory drugs105-107are correlated with an increased risk of developing DSC by up to 2.34 times.Thus,all these factors are positively correlated with DSC and its subtypes.

4.3.Strengths and limitations

One novel aspect of our study is that we used the known varieties of DSCs in our meta-analysis of the association between differing levels of PA and DSC risk.Another strength is that a large sample size was used.Thus,an extensive information sub-analysis was performed.Moreover,strati fication according to the subtypes of DSC,study design,PA domain,gender,and geographic region,as well as adjustment for BMI,smoking,and alcohol intake,was performed.Thus,the results of our study may be more informative and robust than those of a small-scale study based on a speci fic DSC.

A limitation of our study is that the category of PA groups covered significant variations in PA volume.Speci fically,several studies do not have a moderate PA classi fication,and most were classi fied as active PA or inactive PA,with or without PA,and possible and impossible PA.Such variations did not allow us to identify the speci fic types and intensity of PA that might affect its impact on DSC risk.Another limitation was that information about the stage of DSCs could not be extracted.Thus,it could not be determined what effects PA may have to prevent DSC from developing to the next stage.

5.Conclusion

Our systematic review has provided additional comprehensive information about the inverse relationship between PA and DSC risk.The updated evidence from our meta-analysis indicates that a moderate-to-high PA level is a common protective factor that can significantly lower the overall risk of DSC.However,the reduction rate for speci fic cancers may vary.In addition,limited evidence suggests that meeting the international PA guidelines might not significantly reduce the risk of DSC.Thus,future studies should be conducted in order to determine the optimal dosage,frequency,intensity,and duration of PA that can reduce the risk of DSC.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Xingang Lu for providing advice about the analysis.We also thank Ping Lu for guidance and Professor Roger Adams from the University of Canberra for proofreading the manuscript.This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(81774443,31870936)and the 3-year Development Plan Project for Traditional Chinese Medicine(ZY(2018-2020)-CCCX-2001-05).

Authors’contributions

All the authors participated in conceiving and designing the project.FX,JH,CG,and ZC performed the search and metaanalysis;FY,MF,and JH contributed to data analysis and interpretation;YY drafted the manuscript,which was revised by all co-authors.All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript,and agree with the presentation of the order of the author.T

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.T

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found,in the online version,at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2020.09.009.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2021年1期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2021年1期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Author biographies of Editor-in-Chief’s choice

- Risk factors for overuse injuries in short-and long-distance running:A systematic reviewT

- Physical exercise may exert its therapeutic in fluence on Alzheimer’s disease through the reversal of mitochondrial dysfunction via SIRT1-FOXO1/3-PINK1-Parkin-mediated mitophagyT

- Exercise interventions for older adults:A systematic review of meta-analysesT

- he mirror’s curse:Weight perceptions mediate the link between physical activity and life satisfaction among 727,865 teens in 44 countriesT

- Sensor-based physical activity,sedentary time,and reported cell phone screen time:A hierarchy of correlates in youthT