Risk factors for persistent epiphora following successful canalicular laceration repair

Ying-Yan Qin, Zuo-Hong Li, Feng-Bin Lin, Yu Jia, Jun Mao, Cong-Yao Wang, Xuan-Wei Liang

State Key Laboratory of Ophthalmology, Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510060, Guangdong Province, China

Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic canalicular lacerations can be caused by penetrating or blunt injuries, which occur in 16% of eyelid lacerations and 20% of eye traumas[1]. Canalicular lacerations are ophthalmologic emergencies, and timely surgery can minimize the risk of missing the cut end of the canaliculi[2]. These types of operations are typically recommended within 48h of the trauma[3]. The canaliculus can become obstructed if the wounds are not precisely repaired. This can cause symptomatic epiphora, especially in patients with lacerations to the lower canaliculus[4]. Clinicians and researchers currently advocate placement of a silicone stent in the lacerated canalicular to prevent obstruction, which has a record of satisfactory results. Studies have reported that bicanalicular nasal intubation (e.g., the Crawford silicone tube), “one-stitch” canalicular repair with bicanalicular silicone intubation, mono-canalicular nasal intubation, or the placement of a Mini-Monoka tube can all achieve high patency rates after irrigation[5-7]. Nonetheless, these studies have primarily focused on optimal timing for surgery, surgical procedures, and the factors that aあect surgical outcomes. Little is known about the risk factors of epiphora with anatomical patency in patients who undergo successful surgical repair of canalicular laceration. In this study, we described the clinical characteristics of patients with canalicular lacerations, and analyzed the risk factors of post-surgery epiphora with anatomical patency (i.e., irrigation of the lacrimal passage).

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Ethical ApprovalThis study conformed to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee and Institutional Review Board of the Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center of Sun Yat-sen University (No.2018KYPJ100). Informed consent was obtained from all of the patients.

Figure 1 The distance from the distal cut end to the punctum A: The letter D stands for the distance from the distal cut end to the punctum; B: Color photo of the distance from the distal cut end to the punctum.

Figure 2 Deformities of the medial canthus A: Normal control; B: Lacrimal punctum nasal displacement; C: Lacrimal punctum temporal displacement; D: Lacrimal punctum laceration; E: Entropion of the lower eyelid; F: Ectropion of the lower eyelid; G: Ectropion of the lacrimal punctum; H: Blepharal dysraphism of the medial canthus. One score for each deformity.

The medical records of 178 consecutive patients (178 eyes) with canalicular lacerations were collected from Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center of Sun Yat-sen University between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2012. The diagnosis of canalicular laceration was confirmed by gentle irrigation and a thorough slit lamp microscope examination. All the patients underwent anastomosis of the lacerated canaliculus and bicanalicular silicone intubation (Crawford), and the operations were performed by the same surgeon (Liang XW). During surgery, the lacerated end of the canaliculus was identified using operating microscope with/without the help of lacrimal irrigation. The technique of pericanalicular repair was adopted in all the studied patients. The pericanalicular tissue, muscle and skin were repaired with interrupted 6-0 vicryl sutures. All the cases were with patency after irrigation. The inclusion criteria for this retrospective study were as follows: monocanalicular or bicanalicular lacerations, no previous lacrimal history, and anatomical patency after surgical repair. Exclusion criteria were as follows: additional lacerations involving the punctum, lacrimal sac, or nasolacrimal duct, congenital or acquired lacrimal stenosis or obstruction, concurrent with corneal epithelial defect.

Procedure and Data CollectionPatients were observed on day 1 postoperatively with follow-up examinations 7 to 14d after operation. All of the patients were followed up between 4wk and 3mo after the stents were removed. Syringing was performed one week after the stent removal to determine canalicular patency, and all the subjective symptoms of epiphora were noted at the same time.

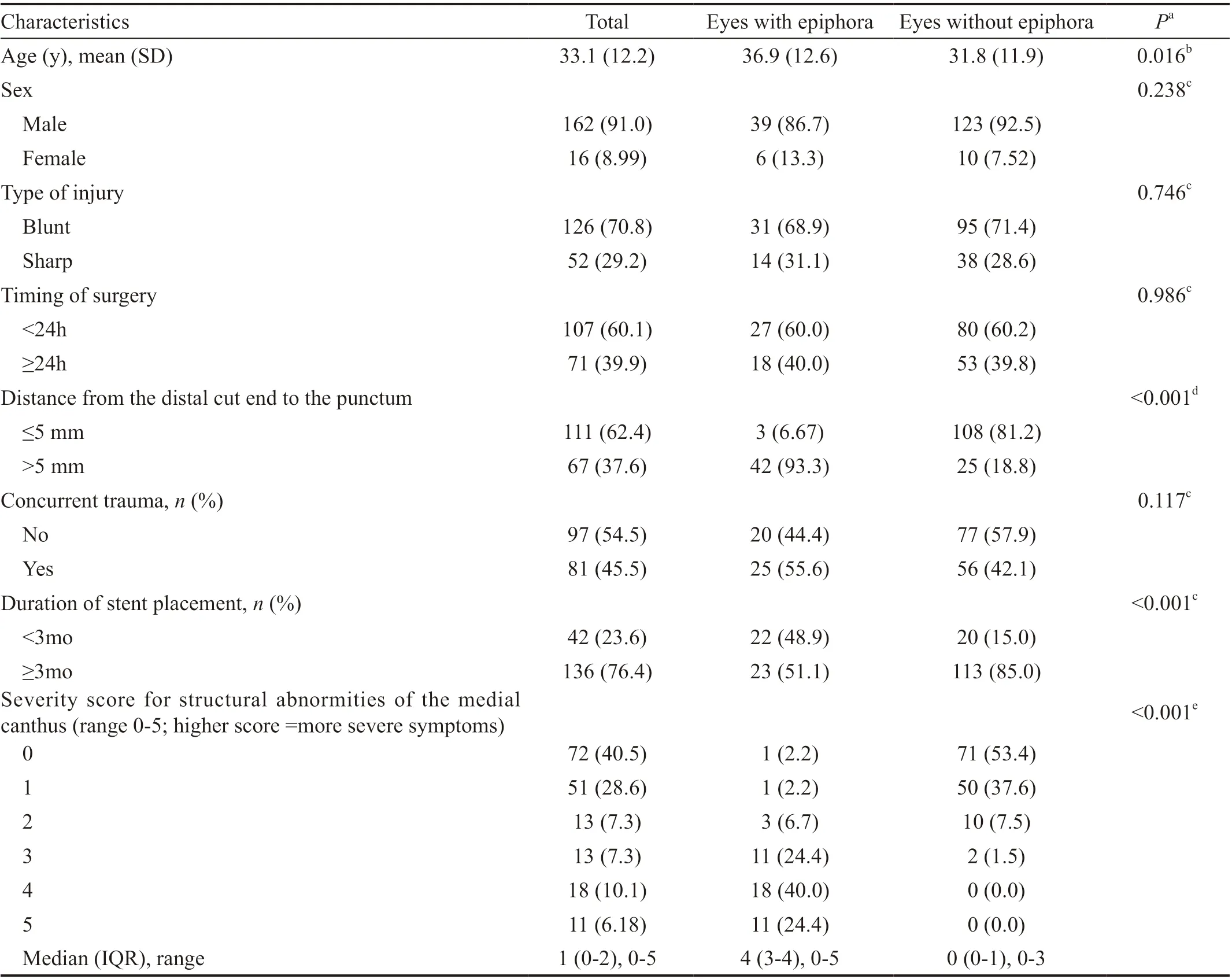

Data were recorded for age, sex, type of injury, timing of surgery, distance from the punctum to the distal lacerated end of the canaliculus (Figure 1), concurrent trauma (e.g., eyelid laceration, ptosis induced by levator detachment, globe injury, and orbital bone fracture), duration of stent placement, and severity score for structural abnormities of the medial canthus.The anatomic and cosmetic outcomes were assessed at the time of stent removal, and these outcomes were evaluated by examining the eyes and eyelids for any deformities that could affect the epiphora, including lacrimal punctum nasal displacement, lacrimal punctum temporal displacement, lacrimal punctum laceration, entropion of the lower eyelid, ectropion of the lower eyelid, ectropion of the lacrimal punctum, and blepharal dysraphism of the medial canthus (1 score=1 deformity; Figure 2). The severity of structural abnormities in the medial canthus was recorded objectively using a grading scale of 0-5 (Table 1). The consistency of the assessment for deformity in the medial canthal area was investigated by Li ZH and Lin FB. A weighted kappa of 0.86 was achieved for all 178 eyes. Epiphora was evaluated according to the scale proposed by Munket al[8](Table 2).Symptomatic epiphora was defined as subjective symptoms of no less than 2 on the epiphora scale (Munk grade 2, 3 or 4).

Table 1 The grading scale for post-surgery structural abnormities of the medial canthus

Table 2 Epiphora grading scale by Munk et al[8]

Statistical AnalysisThe participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between patients with and without epiphora using two-samplet-test for age, Chisquare test, Fisher’s exact test for binary variables with two levels, and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for the severity score for structural abnormities of the medial canthus. We used Logistic regression to detect the potential determinants of epiphora. Variables at a significance ofP<0.05 in the comparisons between patients with and without epiphora were included in the multiple regression model.P-values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All the statistical analyses were performed using a commercially available software package (Stata 13.1, StataCorp, College Station TX, USA).

RESULTS

Characteristic of the Study SubjectsBetween 2005 and 2012, a total of 178 patients with a mean age of 33.1y (range from 1 to 76y) were included in this study. The clinical characteristics of the patients are listed in Table 3. Among them, 25.3% (45/178) who had patency after irrigation also had symptomatic epiphora. The majority of patients were male (91%; 162/178) in both the epiphora and non-epiphora groups. Causes of injury included sharp trauma (31.1%; 14/45) and blunt trauma (68.9%; 31/45) in the epiphora group and sharp trauma (28.6%; 38/133) and blunt trauma (71.4%; 95/133) in the non-epiphora group.

Although 60.0% (27/45) of patients with epiphora and 60.2% (80/133) of patients without epiphora were treated within 24h of injury, 18 patients (40.0%) underwent surgery beyond 24h. Twenty-five patients in the epiphora group and 56 patients in the non-epiphora group suあered from concurrent injuries, such as full-thickness eyelid lacerations (the part of the eyelid that does not include the medial canthus), globe injuries, or orbital bone fractures (Table 3).

Duration of Stent PlacementThe silicone stent remained in place in 22 (48.9%) patients in the epiphora group and 20 patients (15.0%) in the non-epiphora group for less than 3mo. The silicone stent spontaneously detached from lacrimal passages in seven patients (four patients in the epiphora group and three patients in the non-epiphora group). The stent was removed from three patients (one patient in the epiphora group and two patients in the non-epiphora group) before two months due to the formation of punctum/proximal canalicular granuloma. Six patients (four patients in the epiphora group and two patients in the non-epiphora group) asked for early removal of the silicone stent due to foreign body sensation and pain. The stent was removed from 26 patients (13 patients in each group) at the end of the second month after placement. This was achieved by cutting the exposed stent in the medial canthus and withdrawing it from the nose or by taking out the fixed stitches and withdrawing the stent directly from the lacrimal duct.

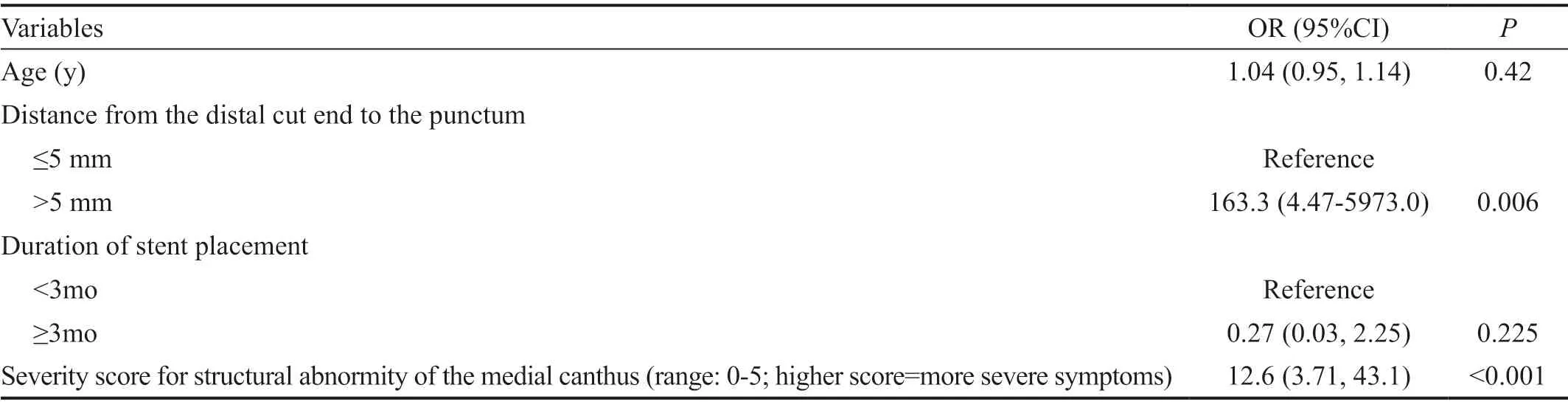

Potential Determinants of EpiphoraAt least 45 of the 178 patients (25.3%) with patency after irrigation had epiphora. To further dissect the determinants of epiphora, we used multiple Logistic regression analysis (Table 4). Patients’ sex, age, type of injury, duration of stent placement, timing of surgery, and concurrent trauma were not found to be significantly associated with epiphora after surgical repair of the lacerated canaliculus (P>0.05). Distances of more than 5 mm from the distal cut end to the punctum were significantly associated with epiphora after surgical repair of the lacerated canaliculus (P<0.01). In addition, symptomatic epiphora was significantly more common in patients with higher severity scores for structural abnormities of the medial canthus (P<0.01).

DISCUSSION

The inappropriate management of canalicular lacerations can result in epiphora. Successful surgical repair of canalicular lacerations can also lead to symptomatic epiphora. This study reviewed a seven-year span of canalicular laceration cases and was the first retrospective case series to evaluate the risk factors of epiphora in patients with anatomical patency after canalicular laceration repair. In the present study, 25.3% (45/178) of the patients with patency after irrigation developed epiphora. Like in previous studies, most of the patients were male (162/178; 91%)[9-11]. No significant associations were identified between symptomatic epiphora after surgical repair of the lacerated canaliculus and patients’ age, sex, type of injury, duration of stent placement, time from injury to repair, and concurrent trauma. Risk factors for postoperative symptomatic epiphora were determined to include the distancefrom the distal cut end to the lacrimal punctum and the severity score for structural abnormities of the medial canthus (epiphora scale ≥2).

Table 3 Characteristics of post-surgery patients with anatomical patency (n=178) n (%)

Table 4 Multiple Logistic regression model for potential determinants of epiphora

Previous studies on canalicular laceration have revealed that late repair can lead to poor clinical outcomes[12-13]. A study recommended repairing canalicular lacerations within six hours to achieve good results[14]. By comparison, another study showed that there were no significant differences between earlier (within 6h) and later repair (7-48h) in terms of the anatomic success rate[15]. A retrospective case series noted that surgery can be feasible within one week and without compromising the success rate. They also asserted that there were no significant diあerences in outcome between surgeries that took place within and after 48h[2]. Our study showed no correlation between the timing of surgery (within 24h or after 24h) and postoperative epiphora in patients who underwent successful surgical repair of their canalicular lacerations. Thus, for patients who have complications, surgeons may consider postponing surgery so that they can wait for the regression of local tissue edema and hemorrhage absorption.

To prevent symptomatic epiphora, meticulous wound repair of the lacrimal canaliculus and a lack of structural abnormities in the medial canthus are essential. The present study identified numerous unsatisfactory cosmetic results, such as lacrimal punctum nasal displacement, lacrimal punctum temporal displacement, lacrimal punctum laceration, entropion of the lower eyelid, ectropion of the lower eyelid, ectropion of the lacrimal punctum, and blepharal dysraphism of the medial canthus. The current study’s results indicate that symptomatic epiphora is significantly more common in patients with higher severity scores for structural abnormities of the medial canthus. We hypothesize that structural abnormities in the medial canthus can lead to compromised lacrimal pump function and symptomatic epiphora as a result. Detailed discussion and additional studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

In recent decades, the technique for canalicular repair has improved considerably due to the implementation of traction sutures, pericanalicular repair, and direct canalicular wall sutures[16-18]. A previous study reported a higher success rate in patients who had been treated with direct canalicular repair than with pericanalicular repair[17]. On the contrary, several authors have observed that direct canalicular wall sutures can further damage the delicate mucosa and induce a suture reaction and tearing of the canalicular wall[19-20]. The present study adopted the technique of pericanalicular repair with a stent insertion in all of the patients. The results indicated that distances of more than 5 mm from the distal cut end to the punctum were closely associated with epiphora after the surgical repair of the lacerated canaliculus. Consistently, a previous study found that distances of more than 6 mm from the distal cut end to the punctum possessed a worse anatomical outcome[21]. We hypothesize that the injury of Horner’s muscle, which located between posterior lacrimal crest and medial aspect of the tarsal plate[22], compromised lacrimal pump function and led to epiphora[23]. More damage might exert to the Horner’s muscle when the distal cut end located more than 5 mm from the punctum as the injury located closer to the lacrimal diaphragm.

However, to rule out the eあect of diあerent stents on postoperative epiphora, all the patients had bicanalicular intubation (Crawford) including monocanalicular laceration and bicanalicular laceration in our study. New devices such as Mini-Monoka were not adopted in the study. Despite the aforementioned limitation, the present study is the first of its kind to show that the location of canalicular lacerations and the severity score for structural abnormities of the medial canthus can be used to prognosticate postoperative symptomatic epiphora. The results also suggest that protecting normal lacrimal punctum and reconstructing the normal structure of the medial canthus can provide beneficial outcomes in restoring canalicular function.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors’ contributions:Li ZH, Liang XW designed the study. Lin FB, Jia Y, Mao J, Wang CY collected the data. Qin YY, Lin ZH and Lin FB analyzed the data. Qin YY, Li ZH wrote the manuscript. Qin YY, Li ZH and Liang XW reviewed the paper.

Foundations:Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81600731); Projects of Science and Technology Research of Guangdong Province (No.2012B031800294).

Conflicts of Interest:Qin YY,None;Li ZH,None;Lin FB,None;Jia Y,None;Mao J,None;Wang CY,None;Liang XW,None.

International Journal of Ophthalmology2021年1期

International Journal of Ophthalmology2021年1期

- International Journal of Ophthalmology的其它文章

- Response of L V Prasad Eye Institute to COVID-19 outbreak in India: experience at its tertiary eye care centre and adoption to its Eye Health Pyramid

- Preliminary studies of constructing a tissue-engineered lamellar corneal graft by culturing mesenchymal stem cells onto decellularized corneal matrix

- Therapeutic potential of Rho-associated kinase inhibitor Y27632 in corneal endothelial dysfunction: an in vitro and in vivo study

- Changes of matrix metalloproteinases in the stroma after corneal cross-linking in rabbits

- A multi-omics study on cutaneous and uveal melanoma

- Eあects of quercetin on diabetic retinopathy and its association with NLRP3 inflammasome and autophagy