叙事视角下的中国少数民族文化宣传汉译英:理论与实践

肖唐金,肖志鹏

一、前言

跨文化交际翻译学从跨文化交际角度探讨翻译理论与实践,结合多个学科视野,具有跨学科、跨文化、跨语言三大特征(参见肖唐金[1]23-38)。鉴于此,跨文化交际翻译学可从多个学科路径开展。这有别于传统的形式等值、功能等值理论。翻译理论可整合其他学科的观点,并根据相关视角提出具体翻译步骤或程序。这一转变可视作“多学科方法论”(multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary approaches)。本文拟从叙事视角探讨中国少数民族文化汉译英的理论建构与实践,充实跨文化交际翻译学这一领域。

二、文献回顾

“叙事”(narrative)是许多学科的一个重要概念,如文学叙事、社会学叙事、二语习得叙事。在不同的领域,叙事涉及的内容、方法、技术手段等有所不同,但都离不开主角、旁观者的经历体会,是构建学科的一条重要路径。叙事学理论起源于20世纪的文学批评研究,弗拉基米尔·普洛普、罗兰·巴特、托多罗夫、热奈特、格雷马斯等为重要研究者。叙事划分为“故事”和“话语”两个大层次,叙事涉及三个层面——词义、句法和词汇,叙事问题涉及三个语法范畴——时间、语体和语式。结构语言学提出了所指与能指两个概念,格雷马斯的符号叙事借用了索绪尔的这一结构语言学观点。语言学中的能指(signifier)是语言符号,而所指(signified)则是客观世界、精神世界中的物体、人物、现象、事实、情感等,包括具体和抽象两个方面。文学叙事中,能指与所指存在一对一、一对多、多对一等现象,值得研究。

在文学创作以及文学研究乃至二语教育中,叙事学理论得到了广泛的运用,其中叙事空间、叙事人称、圆形人物与扁平人物是常提及的概念。根据李世卓的观点[2]14-16,成长小说可体现典型的叙事故事结构:诱惑-出走-考验-迷惘-顿悟-失去天真-认识人生和自我。叙事修辞学指出叙事除了“作者”与“作者声音”外,还涵盖“隐含的作者”与“隐含的声音”。游澜、余岱宗[3]111-119提出了感知叙事理念,包括感觉叙事、知觉叙事两个方面,叙事就是知觉对感觉的组织和整合的结果,即内部对外部世界的概念化,形成对事物和环境事件的认识。文学作品中的人物性格迥异,在文本中的作用各有千秋,感知叙事理论可以让我们透析人物精神世界与外部行为的特点、对应。叙事涉及故事、话语与叙事行为,三个方面有机结合在一起,经过叙事开篇、话题导入和/或话题转移、情节结束三个阶段。方梅[4]1-13研究了话本小说的开场套路,在正式开始叙述前需一段引辞,以“词曰”“诗曰”“话说”之类开场,在话题转移时往往会用上“单说”以及若干互动性、评价性元话语(如“诸位有所不知”“闻所未闻”)。这些模式是话本小说的叙事模式。赵崇璧[5]147-153探讨了重复叙事的空间逻辑,空间重复可分化为聚合、互补、复调三种逻辑形式,对于叙事的贡献各不一样。Swain、Kinnear、Steinman[6]将叙事视角看作社会文化理论的一部分,用于第二语言教育研究。第二语言教育涉及二语习得、翻译教学等,因此叙事视角对于这些领域的理论拓展与实践具有指导性作用。

翻译理论在过去20~30年得到了突飞猛进,已经不再局限于传统意义的形式或功能等值、信达雅了,文化转向、语言学转向、多学科转向成为翻译研究的热点。Baker[7]158-176提出了叙事翻译方法论,将叙事学的观点引入到翻译理论与实践中,受到了House[8]的肯定。Mason[9]36-54从社会学的角度审视了翻译理论与实践,将翻译看作为社会-文本实践(socio-textual practice),目标语文本是协商、强化或挑战权势关系的路径。Snell-Hornby[10]研究发现,自20世纪80年代以来,翻译理论与实践发生了“文化转向”,具体体现在目的论、操纵论、接受美学、法庭翻译、广告翻译、同声传译、基于性别的翻译、基于语料的翻译等理论与实践上,这是对Nida的功能等值论的进一步深化。鉴于翻译理论与实践的文化转向与新时代我们优秀民族文化走向世界舞台的精神吻合,因此有必要从文化角度探讨中国少数民族文化宣传的汉译英。叙事翻译理念提出的时间不长,这方面的研究有限。下面我们将首先介绍翻译的叙事视角,接着通过中国少数民族文化宣传汉译英具体事例阐述叙事翻译模式类型、程序,充实叙事翻译理论框架,点明叙事翻译实践所涉及的方方面面。

三、翻译的叙事视角

Baker[11]为我们阐述了翻译的叙事视角的基本理论。翻译的叙事视角与社会叙事(socio-narrative)或社会学叙事(sociological narrative)路径有着直接的关系,将叙事视为理解世界以及我们在世界的位置、角色的方式,是视野更广、具有建构性质(constructivist)的方式。这一视角源于针对人、环境、环境中传播的故事之间关系的两个假设。其一,对于现实我们经常缺乏直接、不加媒介的接触,具体来讲,我们对现实的接触是通过对我们生活的世界的自我叙事或向他者叙事得以实现的。其二,我们叙述的故事不仅是我们接触现实的媒介,也参与现实的构建。因此,翻译可看作一种叙事(或再叙事)的形式,它构建(construct)而不是表征(represent)用另外一种语言再叙述(re-narrate)的事件和人物(character)。在翻译叙事路径中,译者(包括笔译者和口译者)并非对于翻译行为之外的文化碰撞(cultural encounters)扮演中介作用,而是参与这些文化碰撞的构建(configuring)。译者嵌入在叙事中,通过翻译手段的选择对叙事进行阐述、修改、改变、传播。鉴于此,译者的最重要角色是对叙事、再叙事过程进行干预。叙事视角授予译者充足的自主权(agency),认可他们在社会中扮演的决策性、高度复杂性角色。

根据翻译叙事视角,话语分析单位为一个完整的叙事结构,即一个完整的故事,包含人物、场景、结果、情节等。基于此,这一分析单位既不排除也不主要关注文本中常现的语言模式;与批评话语分析不同,它不是将这些语言模式与抽象、机构驱动的现实世界社会构建或知识形式联系起来,而是将重点一方面放在机构、个人(各个阶层的人物)如何以各种方式构建、传播构成我们世界的叙事体上,另一方面放在译者如何以各种方式干预这一过程。由于完整的叙事结构为话语分析单位,所以我们在翻译实践中应得出几点启示。第一,在翻译叙事路径中,我们不应认为寻找常见的文本模式是较好的方法出发点。个性化、偶然使用的,甚至非文本式的手段可能与常见的文本模式同样重要。第二,叙事可通过各种媒介加以实现,可采用书面与口头文本、图像、表格、颜色、式样、衣着等手段。第三,单个叙事结构会产生局域性影响,也会影响整个叙事结构。第四,各单个叙事结构相互关联,有时界限很难划分,即很难客观区分各单个叙事结构。

要实现翻译叙事路径,我们需要两个具体工具:叙事类型(narrative typology)以及相关叙事特征。叙事类型包括4类:个人叙事(personal narrative)、公共叙事(public narrative)、概念或学科叙事(conceptual or disciplinary narrative)、元叙事(meta narrative)。个人叙事是关于我们在世界中所处位置、个人经历的故事,可自我叙述也可向他人讲述。公共叙事是群体或社区共享的故事。概念或学科叙事是学术或专业叙事,用以解析研究对象。元叙事是具有较为深远地域意义、历史跨度较大的叙事,具有高度的抽象性,如民族主义、启蒙主义、资本主义、共产主义、社会进步、全球化,等等,可看作“我们时代的史诗戏剧”(epic drama of our time)。在翻译实践中,个人叙事与公共叙事经常交互在一起,互相影响,具有辩证统一的关系。出于不同的个人或机构、社会目的,有时译者更突出公共叙事,有时则更突出个人叙事。突出个人叙事是翻译叙事路径受学者们关注之所在。如,第二次世界大战中犹太人遭受过大屠杀,幸存者或受害者家庭成员的叙事成为译者关注的重点。通过翻译的文本,这些个人故事讲述了犹太人遭受的非人待遇、他们的痛苦,形成了一种特殊的语体(genre);透过这些故事,我们可研究译者的选择:翻译的内容与翻译的方式。通过个人叙事,我们也可了解译者如何呈现其社区或社会,这些单个的故事有助于勾勒出社会的整体框架,揭示社会成员的身份、职业、行事目的,等等。翻译叙事路径可体现以下两套特征:(1)选择性内容配置(selective appropriation)、时空性(temporality)、关系性(relationality)、具有因果关系的情节安排(causal emplotment);(2)特殊性(particularity)、类属性(genericness)、规范性(normativeness)、叙事增长(narrative accrual)。因为不可能将经历的每一个细节都融入叙述中,因而内容选择是非常有必要的。内容选择可为故事情节的前景化、背景化服务。叙事需嵌入某个时间、空间里,因而具有时空性。叙事中所涉及的人物、事件、语言项、设计安排、意境都必须与整体叙事相关联。整个叙事结构可能涉及多个故事,其情节应有因果关联。叙事的特殊性指故事的特殊性,叙事的类属性指故事的类型,如申诉、侦探故事,为不同的语体或体裁。叙事往往要对应某些规范,变化应在可接受的范围内。叙事增长意味着各个故事加在一起具有递增作用,可勾勒出整个叙事结构。据此,在翻译叙事方法的实施过程中,译者扮演了重要的角色,目标语文本的内容、形式、规范、细节筛选尽在其掌控之中。译者因而起着目标语文本隐性作者的作用,改变了其传统的源语文本“复制者”的身份。

四、叙事视角与中国少数民族文化宣传汉译英

叙事翻译在中国少数民族文化宣传汉译英中可能起重要作用。原因有二,和本文作者的经历有关。

首先,通过阅读国外学者对中国少数民族文化的研究成果,发现叙事视角使用较为频繁。如:

例1:To manage the ethnic minority groups in frontier areas, the Chinese generally resorted to indirect rule. Regions of great strategic or economic value were governed directly by regular Chinese officials, while peripheral frontier regions in the southwest were ruled throughtusior native chieftains. Although policy varied considerably over time and was interspersed with periods of active conquest followed by the imposition of direct rule, it generally represented an effort to keep the marches pacified with as little effort and expense as possible. The policy was one variant of the venerable and hallowed practice of “using barbarians to rule barbarians” (yiyizhiyi). Thetusisystem developed from the “loose rein” (jimi) policy of earlier dynasties. The idea behind the loose rein policy was to exert some control over chieftains on the fringes of the Chinese empire without forcing the issue in such a way that the chieftains would grow intractable and cut off the relationship. In the Han dynasty, relations with border chiefs under this policy were sporadic; by the Tang dynasty they had grown more formalized and regular. Gradually, prefectures, districts, and garrisons “under a loose rein” were created, and the heads of these new administrative units-largely indigenous non-Han-were allowed considerable latitude in local affairs and could pass on their positions hereditarily. Thetusisystem was the next stage in the development of these administrative units. It began under the Yuan and was fully articulated under the Ming-complete with regulations governing rank, promotion, demotion, rewards, and punishments. There were basically three categories of officials within the system.

(文章来源:Robert D. Jenks: Insurgency and Social Disorder in Guizhou-The “Miao” Rebellion 1854-1873, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1994[12]39)

参考译文(本文作者自译):为了妥善管理边陲地区少数民族,汉人通常采取本土治理(也称间接治理)方式。具体来讲,战略意义或经济价值更大的地区由汉人官员来管理,西南边陲地区则由土司或地方头目负责。虽然在历史上这一政策不是一成不变,期间存在汉人直接统治,但总体上来讲,土司制度表明中央政府希望花费最小的人力物力来管理边疆少数民族地区。这一政策实际上体现了中国封建政权笃信的统治观念,即“以夷制夷”。土司制度源于先前朝代的“放手”(羁縻)政策。这一政策的理念是,宽泛管理,不对边远地区的头目强加控制,以免造成关系割裂,局面不可收拾。汉代,边疆头目与中央政府的关系较为随意,到了唐代,这一关系制度化、正规化了。渐渐地,在羁縻政策影响下,道、府、卫戍区得以建立起来了,这些新行政单位的头目,一般来讲非汉人,在地方事务方面有了一定的权限,且可让其权位世袭。在这些机构建立之后,就出现了土司制度。土司制度始于元代,在明代得到了全面发展,有完整的级别、提拔、贬职、奖赏、惩罚规章制度,土司基本上分为三类。

再如:

例2:The term “raw Miao” used by Yan Ruyi requires comment. In addition to the traditional classification of the Miao mentioned earlier (i.e., according to such criteria as clothing and physical characteristics), the Chinese used another standard for differentiation. It was a very old one that was also applied to steppe nomads, Taiwan aborigines, and other “barbarians”. The Miao were categorized as either raw (shengMiao) or cooked (shuMiao). By definition, the former lived in remote areas, were beyond the pale of Chinese civilization and political control, paid taxes and did labor service, and had absorbed some measure of Chinese culture. In other words, one group was almost totally unassimilated, while the other group was assimilated to varying degrees. The terms “cooked” and “raw” are a reflection of the way the Han looked upon the Miao and other minorities. Both are essentially pejoratives, and as such they provide an important insight into Han attitudes toward minorities.

(文章来源:Robert D. Jenks: Insurgency and Social Disorder in Guizhou—The “Miao” Rebellion 1854-1873, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1994[12]34-35)

参考译文(本文作者自译):严如熤使用过“生苗”这一术语,这里值得一提。我们前面提过,苗族的分类传统上依据服装和身体特征等标准,但在中国还有另外一种区分标准。这一分类其实不是什么新鲜事,曾经在对草原游牧民族、台湾原住居民和其他“夷人”分类时也采用过此标准。依据此标准,苗族可分为“生苗”或“熟苗”。我们不妨将前者界定为那些生活在边远地区的苗民,他们位于中国文明和政治管理的边缘地带,缴纳税收,从事苦力活,吸收了一定程度的汉文化。换言之,“生苗”没有被汉族文化同化,而“熟苗”不同程度上被汉族文化同化了。“生苗”与“熟苗”之分反映了当时汉族对苗族和其他少数民族的看法。两种说法本质上是贬义的,正因为如此,可一定程度揭示当时汉族统治者对少数民族的态度。

例3:How do the Hmong fit into broader historical, geographical, and social contexts? The people with whom I worked are a subgroup of Hmong, or Miao/Yao speaking people, an ethnic minority who have lived on the fringes of powerful states, primarily China, for centuries, but where they originated and much of their subsequent history is something of a mystery. Part of the problem is that the Miao in China did not have a writing system of their own, so scholars have had to rely on Chinese documentary evidence to reconstruct the Hmong or Miao past. The Shujing (Book of Documents) places the Miao in China in the third century B. C. Although they are documented in the Zhou and Qin dynasties, records on them become rare afterwards, with only a few brief mentions in the Tang and Song dynasties, until they reemerge in official documents in the Yuan and Ming dynasties. This has led to confusion as to their whereabouts during the intervening centuries. some scholars postulate that the Miao/Hmong originated in southern China.

The ethnonym Miao, and subsequently Meo in Laos and Thailand, also has been a source of confusion, and many explanations are given for the name. Yang Dao, a Hmong scholar, has stated that the Miao is a Chinese term meaning “barbarian”, but in China there are still many people who are called and who call themselves Miao. In the diaspora following the Vietnam War, Miao/Hmong have migrated to the United States, Australia, French Guyana, Canada, and Europe, and in these countries they call themselves Hmong.

(文章来源:Patricia V. Symonds: Gender and the Cycle of Life: Calling in the Soul in a Hmong Village, Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2004: pp xxiv-xxv[13])

参考译文(本文作者自译):苗族如何融入更广的历史、地理与社会氛围中?我所交往的苗族是苗族的一个分支或苗/瑶语系民族,多个世纪来生活在大国(主要是中国)的边陲,但其来源地与历史流变确是有些神秘。原因之一在于中国苗族没有自己的文字系统,因此学者们只得依赖相关的中国文献来重构苗族的历史。《书经》(又名《尚书》)认为中国苗族起源于公元前3世纪。虽然在周朝、秦朝也有关于苗族的记录,但之后类似的记录偏少,唐、宋期间偶尔提及苗族,在元、明期间官方文件中再次记录了苗族的相关情况。正因为如此,人们不禁对中间空隙时间苗族的情况感到迷惑。一些学者认为苗族起源于中国南方。苗族在中国、老挝、泰国称呼有所不同,这也造成了一定的认知混淆,许多学者对苗族的称号给予了解释。苗族学者杨道指出,在汉语中“苗”是一个轻蔑的称呼,意味着“野蛮”,然而在中国仍然有许多人称作苗族或自称苗族。在越南战争后的大迁徙中,部分苗族迁徙到美国、澳大利亚、法属圭亚那、加拿大和欧洲,在这些国家他们自称为“蒙人”(苗族)。

例1的时间概念明确,土司制度的兴起与发展始终沿着朝代这条时间轴,出现的主人公为地方少数民族头领、汉族中央政府,故事内容明确。例2的时间概念没有明确化,但“生苗”“熟苗”两个概念的界定体现了叙事特征,即苗族与汉族文化融合过程与程度。例3的作者将苗族置于中国历史发展长河之中,也将苗族的变迁与跨境列入讨论之中,且涉及中国历史典籍《尚书》,叙事特征明显。西方学者对中国少数民族文化的研究很大程度上基于中国学者的研究成果,是另外一种“翻译”或“变译”。因此,叙事视角可以用于中国少数民族文化宣传汉译英中。

第二,本文作者参加过中国-东盟教育交流周、生态文明贵阳国际论坛翻译以及贵州民族大学对外宣传资料的汉译英工作,发现叙事视角在这些场合作用较大。如:

例4:

六十六年栉风沐雨,六十六年薪火相传;六十六年奋发蹈厉,六十六年玉汝于成。

贵州民族大学创建于1951年5月17日,是新中国创建最早的五所民族院校之一,是中国共产党领导贵州各族人民翻身解放,真正实现民族平等团结,走向共同繁荣的重要成果。66年来,一代代民大人筚路蓝缕,以启民智;弦歌不辍,匡正学统。近十年成绩斐然:

2006年,获批硕士学位授予权单位;

2007年,明确为省属重点大学;获评为教育部本科教学评估“优秀”等次;

2008年,成为国家民委和贵州省政府共建高校;

2012年,更名为贵州民族大学;获批服务国家特殊需求博士人才培养项目“西南民族地区社会管理”并于次年招生,实现贵州省人文社科博士零的突破;

2014年,建成并入住大学城新校区;同年,获批为中国政府奖学金来华留学生接收院校;学校更名后第一次党代会明确“建成国内高水平一流民族大学”奋斗目标,以此落实教育部、国家民委、贵州省委、省政府对我校的关怀和要求,回应全省各民族同胞对我校的厚望,更好地服务贵州经济社会文化发展。

光阴荏苒、岁月留心,66年来沐浴着党的关怀和民族政策光辉成长壮大的贵州民族大学,始终与民族地区和少数民族同胞同呼吸共命运,奏响创新创业的奉献之歌。

学校现有两个校区,花溪校区坐落于山清水秀、被誉为“高原明珠”的贵阳市花溪区,大学城校区坐落在产城融合创新、生态文明示范的贵安新区,办学条件极大改善,软硬件设施良好地服务教研实践,19000余名莘莘学子在此成长成才。自建校以来,已为社会输送10万余名各级各类人才。

学校有21个学院、78个普通本科专业;1个博士项目;6个一级学科硕士点,涵盖52个二级学科硕士点,5个专业学位硕士点。拥有一支结构合理、高学历高素质、发展趋势良好的师资队伍,成为学校发展最宝贵的核心资源;其中一大批杰出的国家级、省级专家学者具有全国学术影响力和高尚的师德教风。

参考译文(本文作者自译):With sixty-six years’ weather-beating, we have come along; with sixty-six years’ efforts, we have made our name.

Guizhou Minzu University, founded on May 17th, 1951, is one of the five earliest minorities-oriented universities in China. It is a fruit of toil of all peoples in Guizhou, led by the Communist Party of China, as well as a mark of national equality, unity and shared prosperity.

Over the past sixty-six years the staff and students of Guizhou Minzu University, generation after generation, have left remarkable footprints in education, contributed to talent cultivation and formed a solid tradition of learning:

In 2006, the university was approved as qualified for issuing Master’s Degree;

In 2007, the university was specified as a key provincial university, and secured the rank of “excellence” in the Ministry of Education’s Undergraduate Education Evaluation;

In 2008, the university was ratified as jointly developed by the State Ethnic Affairs Commission and Guizhou Provincial People’s Government;

In 2012, the university changed its name from Guizhou Minzu Institute to Guizhou Minzu University, and in the same year, it was ratified as qualified for running the doctorate program for special national needs—“Southwest China Ethnic Areas’ Social Management”; in the following year, it started to enroll doctorate candidates, which was a breakthrough in the field of liberal arts in Guizhou;

In 2014, the new campus in University Town was basically completed and started to host undergraduates. In the same year, the university was ratified as qualified for admitting foreign students on the scholarships of the Chinese government. The university, whose name changed from Guizhou Minzu Institute to Guizhou Minzu University, for the first time specified its target at its first Communist Party of China Congress: to build the university into a high-level first-rate minorities-oriented university, as a response to the support and requirement from Ministry of Education, the State Ethnic Affairs Commission, Guizhou Provincial CPC Committee, and Guizhou Provincial People’s Government as well as the high expectations of Guizhou’s peoples for better services to local economic, social and cultural development.

Time goes on and on, and our heart becomes stronger and stronger. Over the past sixty-six years the university has been receiving support and care from the Communist Party of China and the Chinese government in policy and funding; it has been contributing to the development of minority people and minority areas; it is now singing a song of innovation-based contributions.

The university has two campuses now. The Huaxi Campus is located in Huaxi District, known as “Pearl of Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau” for beautiful mountains and charming waters; the University Town Campus lies in Gui’an New District, where industries, urban construction, innovation and ecology are integrated. The university’s conditions have been much improved, with well-operating facilities for teaching and research, and over 19,000 students are thriving on this land. Since the founding of the university, over 100,000 talents of various fields have been cultivated for the society.

The university has 21 schools, 78 undergraduate majors, 1 doctorate program, 6 level-1 master degree programs covering 52 level-2 master degree programs, and 5 professional master degree programs. It has a well-structured, high-degree, highly-qualified, well-developing faculty, which is the most precious resource for its development. Of the faculty, there are a big number of nation-level and province-level experts and scholars with nationwide academic influence and noble professorship.

例5:

“生态文明与反贫困”主题论坛是生态文明国际论坛重要的组成部分之一。自2014年来,今年是连续第三年举办。去年在第三方评估中被评为6个优秀分论坛之一。2016年主题论坛由国务院扶贫办、北京大学主办,中国国际扶贫中心、北京大学贫困地区发展研究院、中国社科院社会学研究所、贵州省社科院、贵州省扶贫办、贵州民族大学、中国新闻社贵州分社、德国巴伐利亚州农村研究院、德国汉斯·赛德尔基金会、普定县人民政府承办,时间为3天。将邀请联合国组织和国际反贫困机构、国内外反贫困研究专家、中国知名反贫困社会组织、本土扶贫领域学者共约100人与会。除主会场外,还将在贵州民族大学、普定县设立分会场,提供更充分、更深入的讨论机会。同时在普定县对生态治理与山地农业进行观摩考察。

举办本主题论坛的目的在于:1.深入讨论减贫行动的国际合作与协作,探讨构建更具开放性的国际减贫工作协作机制;2.在习总书记精准扶贫论述体系的指引下,就精准脱贫工作的社会合作策略、能力建设策略、技术应用与社区发展同步策略进行深入讨论;3.深入讨论公共政策支持生态文明与精准脱贫同步推进的策略与路径。

本主题论坛已成为减贫领域国际对话与合作,官方与民间对话与协作,理论、学术领域与行动、实践领域对话与合作的重要论坛。论坛参与者包括了国际、国内重要的减贫政策与理论研究者,资深的减贫行动者和减贫社会工作者。本分论坛的举办,对于更加深入、更加精准地推进我国的精准脱贫工作,具有直接的价值和意义,同时,对于梳理中国的反贫困行动经验,构建减贫经验基础之上的中国政策、行动及话语体系从而支持减贫领域内的国际合作,扩大中国对全球反贫困事业的贡献,都将产生积极的意义。

分论坛设三个主题:1.生态文明建设与精准脱贫,2.贫困治理与社会建设,3.亚热带农业发展与减贫。分论坛将延续“环境可持续”与“社会可持续”理念,探讨生态文明建设、社会建设、乡村治理如何支持精准扶贫、精准脱贫;探讨如何构建社会参与基础上的大扶贫项目治理格局、乡村善治基础上的反贫困行动,建设扶贫新路的社会基础;探讨中国扶贫经验如何支持扶贫外交、构建全球反贫困行动共同体。

本届论坛的主要亮点:1.贵州是全国脱贫攻坚的主战场、示范区和样板省,在全国的脱贫攻坚中承担着重要使命。因此,对贵州扶贫开发实践的深度了解和关注是寻找贵州脱贫攻坚智慧的前提。本次论坛的参会者,既站在全国的高度,又立足贵州的实践,如王春光、王晓毅、雷明、向德平、张琦、左小蕾等学者均长期在贵州从事调查研究,对贵州的脱贫攻坚与经济社会发展有比较深入的了解和独到的见解。

2.作为本次论坛主要筹办力量之一的贵州民族大学社会建设与反贫困研究院,以王春光、孙兆霞、毛刚强等人为代表的研究团队,从2011年成立起到现在,一直致力于社会建设与反贫困相结合的研究,提出以社会建设为基底的反贫困理论与实践路径,在巩固与中国社会科学院社会学所、复旦大学、中山大学等机构的长期深度合作基础上,不断开拓与国内多个反贫困研究领域重要的机构和学者的合作。以开放的姿态,汇聚国内外反贫困的智慧,三年来成为为生态文明与反贫困的学术支撑平台,并通过这一平台不断提升本研究院研究成果的水平。

3.本论坛的参会者,既有政府官员、理论研究者,还有反贫困的行动研究者,如汤敏、杨团、张兰英、杨丽君等,长期在中国反贫困的实践中,进行反贫困理论、方法与路径的本土化探索,将国际发展、国际援助的理论与方法结合中国的反贫困实践,创造性地开拓出了若干重要的本土理论与方法,取得了实践的成功。而本论坛将他们聚集在一起,也提供了一个交流、发声与传播的平台,让他们的经验能够在更大范围内影响中国的扶贫实践。

4.贵州省刚刚召开了深入学习贯彻习近平总书记关于扶贫开发重要讲话精神座谈会、贵州省第二次大扶贫战略行动推进大会、专题研究黔西南州工作的贵州省委常委会议等脱贫攻坚领域的重大会议,进一步统一了贵州省脱贫攻坚的思想和步调。本论坛的召开,也将围绕这些会议精神,为贵州省脱贫攻坚提供智力支持,努力探索脱贫攻坚创新的贵州经验。郑永年、叶兴庆、黄承伟等著名学者将从贫困治理到国家治理、治国理政进行理论探讨和政策支持研究。

5.在从反贫困实践中,总结多民族文化中的地方智慧尤其是生态智慧。参会嘉宾的长期研究蕴含了从精准扶贫到可持续发展的智慧,能够回应城乡可持续发展、农业文化遗产、人类文化多样性等诸多前沿领域的问题。

6.本论坛设置专门的分论坛,邀请中国科学院喀斯特生态系统观测研究站科学家张信宝等在贵州喀斯特地区长期从事生态恢复与治理研究、喀斯特地区生物资源利用研究及减贫实践的学者以及朱启臻、徐启智等学者在生态农业、亚热带农业发展以及生态建设与美丽乡村、农业合作等不同视角对喀斯特生态脆弱地区的减贫进行探讨。

7.本论坛已成为减贫领域国际对话与合作的重要平台。从2014年以来,特别注重主办与承办机构多元互补的框架设计,今年本论坛由国务院扶贫办、北京大学主办,中国国际扶贫中心、北京大学贫困地区发展研究院、中国社会科学院社会学研究所、贵州省社会科学院、贵州省扶贫办、贵州民族大学、中国新闻社贵州分社、德国巴伐利亚州农村研究院、德国汉斯·赛德尔基金会、普定县人民政府承办。这些机构既有3年来一直坚守的主办与承办机构,保证了论坛的内在动力与品质积淀的可持续性,同时又不断地在吸引和吸纳一些新的机构特别是国际机构的参与,在扩大其影响力的同时,彰显出论坛的活力和魅力。从参会嘉宾的角度看,包含了国际减贫与发展组织负责人、外国政府官员以及从事反贫困研究的学者,通过交流,深入讨论减贫行动的国际合作与协作,探讨构建更具开放性的国际减贫工作协作机制,对于梳理中国的反贫困行动经验,构建减贫经验基础之上的中国政策、行动及话语体系从而支持减贫领域内的国际合作,扩大中国对全球反贫困事业的贡献,都将产生积极的意义。

8.本论坛在举办形式上力求创新。采取“一主两副”的形式。除主会场外,还分别在贵州民族大学、普定县设立分会场。3年来一直在贵州民族大学设立分会场,使国家级国际性的会议能够走进大学,更加彰显出会议学理与学术的特质,同时也为大学的学科和学术发展提供了资源。三个会场三个主题,力求进行更加深入的探讨。特别是在普定县设立分会场,这是生态文明贵阳国际论坛历史上第一次在县一级设立分会场。我们将把国内外专家学者及反贫困民间组织代表请到普定县去,先实地观摩考察,再集中研讨。

参考译文(本文作者自译):

AbriefintroductiontotheForum

I.Background

“Eco-civilization and Anti-poverty Work” is an important theme forum of the Eco Forum Global Forum Global Annual Conference 2016. Starting in 2014, this is the third consecutive year for its convening. Last year, “Eco-civilization and Anti-poverty Work” was listed by an independent assessment agency as one of the six excellent sub-forums for the Conference. In 2016, the Forum is sponsored by the State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development and Beijing University, and hosted by International Poverty Reduction Center in China, Institute on Poverty Research in Beijing University, Institute of Sociology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Guizhou Province Academy of Social Sciences, Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development of Guizhou Province, Guizhou Minzu University, China News Service in Guizhou, Bavaria Rural Research Institute of Germany, Hanns Seidel Stiftung, Germany and People’s Government of Puding County. About 100 scholars and experts from UN organizations, international anti-poverty agencies, domestic and international anti-poverty institutes, renowned domestic anti-poverty social organizations, and domestic poverty reduction research fields will be invited to attend the forums. Besides the main conference site, Guizhou Minzu University and Puding County will host the sub-forums. There will be sufficient opportunities for discussions on anti-poverty issues.

II.Purposeandsignificance

The purpose of the Forum lies in three aspects. First, it is a way of further exploring poverty reduction actions and relevant international cooperation and coordination as well as an open coordinated working mechanism for international poverty reduction. Second, under the guide of President Xi Jinping’s targeted poverty alleviation ideology, it aims at discussing strategies involving social cooperation, capability construction, and coordinated technology application and community development. Third, it intends to seek strategies and approaches for support of public policies for coordinated eco-civilization and targeted poverty alleviation.

The Forum has become an important platform for international dialogue and cooperation in poverty reduction, dialogue and coordination between the government and the folk, and dialogue and cooperation between theoretical academic fields and action or practice. The participants present include renowned international and domestic experts, and practitioners and social workers in poverty reduction. The Forum is conducive to the promotion of China’s targeted poverty alleviation, the summary of experience regarding China’s anti-poverty work, and the formulation of China’s policies, action and discourse system based on poverty reduction work so as to boost international cooperation against poverty and expand China’s contributions to global poverty fight.

Ⅲ.Themesandmaincontent

The Forum includes three themes, namely, eco-civilization development and targeted poverty alleviation, poverty governance and social development, and subtropical agricultural development and poverty reduction. The sub-forums will carry on the notions of “environmental sustainability” and “social sustainability”, explore such issues as eco-civilization development, social development, rural governance as support for accurate poverty alleviation, and targeted poverty alleviation, discuss such issues as social participation-based poverty alleviation governance models, rural governance-based anti-poverty action, and social basis for new poverty alleviation approaches, and tackle such issues as China’s experience of poverty alleviation for poverty alleviation diplomacy, and global commonwealth for anti-poverty action.

IV.Aspectsworthmentioning

1.Guizhou is a main poverty reduction province in China, and should become an example in the fight against poverty. The understanding of experience and practice is a prerequisite for formulating the wisdom tackling deep-rooted poverty in the province. The participants present view the issue at national and provincial levels simultaneously, such as Wang Chunguang, Wang Xiaoyi, Lei Ming, Xiang Deping, Zhang Qi and Zuo Xiaolei, who have made a long-time study on poverty in Guizhou and are familiar with the status quo and challenge and accordingly show insights into the ways out socially and economically.

2.As a main planner of the Forum, Institute of Social Development and Poverty Reduction of Guizhou Minzu University, with Wang Chunguang, Sun Zhaoxiao and Mao Gangqiang as main team members, have devoted to the combination of social development and poverty alleviation since 2011 when it was founded, proposing social development as the basis for anti-poverty theory and practice. Also, in expanding ties with many other anti-poverty institutions and scholars, it has accumulated much wisdom in poverty reduction in a way open to domestic and international contributors. The institution has become an important platform for the research on eco-civilization and anti-poverty work over the past 3 years as more and more academic results have been achieved.

3.The participants present include government officials, theorists and practitioners, such as Tang Min, Zhang Lanying and Yang Lijun, who have worked long in China’s poverty reduction and hence explored localized strategies, approaches and means concerned. Their presence at the Forum is a way of making known their achievements and voices to the public.

4.Recently meetings have been convened in Guizhou, studying President Xi Jinping’s speeches and demands for poverty reduction in China and working out some strategies and tactics for poverty alleviation in southwest Guizhou, that is, Qianxinan Prefecture. This forum is a plus to the efforts that have been made, and will lead to some valuable suggestions on poverty alleviation and coordinated work in Guizhou’s poverty-stricken areas. Eminent scholars, for instance, Zheng Yongnian, Ye Xingqing and Huang Chengwei, are to voice on issues from poverty governance to national governance and national policies.

5.The Forum is to summarize some wisdom, particularly eco-wisdom, based on anti-poverty practice. The guests present have long studied poverty reduction in China, and thus are able to offer valuable advice on targeted poverty alleviation, sustainable development, urban and rural sustainable development, rural cultural heritage, and human cultural diversity—new issues in the world.

6.The Forum has set sub-forums inviting such famous scholars as Zhang Xinbao, who have been studying eco-restoration and governance, utilization of karst bio-resources and poverty reduction in Guizhou, and such eminent experts as Zhu Qizhen and Xu Qizhi, who have been exploring eco-agriculture, subtropical agricultural development, and eco-development, beautiful rural areas and agricultural cooperation in eco-vulnerable karst areas for the sake of poverty reduction.

7.The Forum has become an important platform for international dialogue and cooperation in poverty reduction. Since its launch in 2014, attention has been paid to the design of framework regarding the pluralistic complementation between the sponsoring and hosting agencies. This forum is sponsored by the State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development and Beijing University, and hosted by International Poverty Reduction Center in China, Institute on Poverty Research in Beijing University, Institute of Sociology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Guizhou Province Academy of Social Sciences, Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development of Guizhou Province, Guizhou Minzu University, China News Service in Guizhou, Bavaria Rural Research Institute of Germany, Hanns Seidel Stiftung, Germany and People’s Government of Puding County. These agencies have participated actively in the Forum over the past 3 years and hence accumulated much experience in improving the conference quality. Also, since 2014, new agencies, particularly international ones, have appeared as main participants in each forum, which have expanded its influence and demonstrated its vitality. The guests present include leaders of international poverty reduction and development organizations, foreign government official, and experts on poverty alleviation, who have profoundly discussed issues related to international cooperation and coordination concerning poverty reduction, an increasingly open coordinated work mechanisms for international poverty reduction, and the formulation of China’s policies, action and discourse system based on anti-poverty experience so that international cooperation in poverty reduction can be boosted and China’s contributions in this regard can be increased.

8.The Forum aims at innovation in convening—one main conference site and two sub-forum sites. Besides the main conference site, Guizhou Minzu University and Puding County are the sub-forum sites. Over the past 3 years Guizhou Minzu University has been a sub-forum site, highlighting the notion of holding international and state-level conferences in higher education institutions in a bid to show academic features and promote academic disciplinary development. The three conference sites have a different theme each, the purpose of which is to deepen discussions. For the first time the Forum has its sub-forum at the county level—Puding County, the purpose of which is to organize domestic and international experts for field work and on-the-spot surveys so that better achievements can be made.

例4通过时间线索将贵州民族大学的发展旅程真实地再现,译文遵循了原文的叙事特征,将贵州民族大学这所历史悠久的民族院校的进步、成就加以复述。例5是2016年生态文明贵阳会议的论坛介绍,涉及反贫困工作与生态文明的协调发展,时间点与反贫困、生态文明协调发展相互关联,主人公包括学者、政府、群众(特别是贵州的少数民族),译文对这些叙事特征忠实地加以再现。这两个例子的启发是:叙事可与翻译结合起来,并可能有具体的叙事翻译模式出现。

叙事视角的关键因素包括人物、场景、情节概述,可能还包括寓意或评价。在中国少数民族文化汉译英的过程中,译者应注意源语文化和目标语文化的差距,该差距表现在对故事场景、人物、事件的陌生性(foreignness)上。译者需要尽量缩短这种文化差距,有必要时采取注释、增译、人名的变化等手段。Nord[14] 93-101曾探讨过Alice in Wonderland(爱丽丝漫游记)这一童话小说在英译德、英译法、英译意大利语中的格式变化,涵盖人物名称本土化、小说中插入的儿歌形象化重构等一系列措施,以便让目标语受众更容易接受译本。由此产生的效果包括文本可读性的加强、读者兴趣的增加、参与小说人物讨论活动的读者人数上升等。 Watson[15]在将《论语》(The Analects of Confucius)翻译成英语时给我们树立了示范作用。试看下面的例子:

例6:

(《论语》述而篇第七:第18节)子所雅言,《诗》、《书》、执礼,皆雅言也。

译文:The Master used the correct pronunciations when speaking of theOdesandDocumentsor the conduct of rituals. On all such occasions, he used the correct pronunciations. (As opposed to the pronunciations of Confucius’ native state of Lu)

在例6中,Watson以叙事的方式描述了孔子讲述经典著作时使用的“官方发音”(即陕西语音),该语音在开展周礼时所采用,为孔子所推崇。译者特别注释了“有别于孔子出生地鲁国的发音”,放在脚注里。这是译者缩短文化距离的措施,结合整个译文前言部分对《论语》的主张的介绍,西方读者更容易孔子的教诲。另外,《诗》(即《诗经》)、《书》(即《尚书》)采用了英语中常见的文学味道较浓的词汇Odes、Documents,较为通俗易懂,加之使用了斜体,可提醒读者这是两部中国古代经典著作。Watson的《论语》译著于2007年由美国哥伦比亚大学出版社出版,迄今已有12年之久,国际影响较大,与其在某些部分采用叙事的模式所产生的效果有关。

Watson的叙事翻译模式在中国少数民族文化宣传汉译英中可模仿。试看下例:

例7:

《阿蓉》是苗族叙事歌,流传于黔桂交界的都柳江、月亮山、大苗山和雷公山下的榕江、从江、雷山、丹寨、三都、荔波等县的苗族地区。传说在古代,古州杨家湾辣子寨有一个大苗寨,寨中羲公和欧奶生有一女,名叫耶蓉,尊称阿蓉。阿蓉生得洁白漂亮,亭亭玉立,既聪明伶俐,又心灵手巧,更有一副好歌喉,远近闻名。长大后,远近求亲者踏破门槛,她都不如意。阿蓉爱上摆内寨的后生阿珙,阿珙长得英俊、彪悍,是个出了名的歌师和芦笙手。最后,阿蓉不为钱财所心动,也未遵姑表亲的风俗,只与阿珙定下终身,并与官府展开了斗争,最后在众亲友的帮助之下,终于与阿蓉结为夫妻。作品意义深刻,很有鼓舞作用,现在当地的苗族群众仍以会唱《阿蓉》为荣,而其故事内容也成为鼓藏祭礼内容之一,足以见阿蓉在苗族心中的地位。

参考译文:A Rong is a narrative of the Miao people (known as Hmong in international academic community) in China, popular in the Miao areas of Liujiang River, Moon Mountain and Big Miao Mountain on the border of Guizhou and Guangxi and the Miao areas of Rongjiang, Congjiang, Leishan, Danzhai, Sandu and Libo Counties at the foot of Leigong Mountain. According to the legend, in ancient times there was a big Miao village in Yangzhouwan of Guzhou, where Xigong (husband) and Ounai (wife) had a daughter named Yerong, respectfully called A Rong. The daughter was fair, beautiful and slender as well as bright and smart, with a sweet voice known near and far. When she grew up, many young men came to her home for courtship, but she was not interested in them. In fact, she felt attached to a lad named A Gong in Bainei Village, a famous singer and Lusheng player, who was handsome and strong. She did not give in to the temptations of money or obey the tradition of marrying her cousin, but made a vow of marriage with A Gong, and they fought together against the corrupted government. Eventually, with the help of their relatives and friends the two lovers got married. This story occupies an important place in many people’s hearts, for the Miao people take pride in being able to recite the instructive story of A Rong. The narrative has significant value in literature, and is part of Miao’s Guzang Festival (a sacrifice celebration held every 12 years) celebrations.

在上述译文中,译者有意识在“苗族”“鼓藏节”两个重要的文化负载词上加括号注释,让西方读者更好地了解中国少数民族文化,即苗族文化。另外,鉴于“羲公”“欧奶”两个人名在西方读者看来较为陌生,特加上括号注释其分别为丈夫、妻子,加强故事的可读性。可以看到,译者在这一过程中扮演着重要的角色,译者的主体性得以体现出来。以上叙事是公共叙事,元叙事表现的是坚贞不渝的爱情与不屈不挠的正义精神。译文复制了原文的两种叙事。以上叙事翻译模式可称为“加注式叙事翻译模式”,源语与目标语文本的关系、译者与原作者的关系、源语文化与目标语文化的关系、源语读者与目标语读者的关系可通过下图加以表示。

图1表明:1)目标语文本作者(译者)与源语文本作者存在互动关系,与源语文化、源语文本、源语文本读者之间的关系是通过源语文本作者来加以实现的。2)目标语文本作者(译者)与目标语文化、目标语文本、目标语读者存在互动关系,而源语文本作者与目标语文化、目标语文本、目标语读者之间的关系是通过目标语文本作者(译者)来加以实现的。3)源语文化催生源语文本,源语文本的针对对象为源语文本读者;同理,目标语文化催生目标语文本,目标语文本的针对对象为目标语读者。总体来讲,两种关系皆为单向式。上图揭示的关系说明源语文本作者、目标语文本作者(译者)是“加注式叙事翻译模式”的中心,在跨文化交际过程中,目标语文本作者(译者)作用最为突出。“加注式叙事翻译模式”注重译者的作用,但总体上对源语文本修改幅度有限,基本遵循了奈达的“功能等值”或“动态等值”模式。

20世纪80年代中期,西方翻译界出现了翻译的“文化转向”(cultural turn)。Snell-Hornby[10]特别提及“翻译操纵派”(Manipulation School)。该流派强调其目的是建立文学翻译研究的新范式,Gideon Toury(注重描写翻译研究)、José Lambert和Hendrik van Gorp(注重描写翻译模式研究)、Susan Bassnett(注重戏剧翻译研究)、André Lefevere(注重改写翻译研究)为代表性学者。“翻译操纵派”旨在从描写、目标导向、功能、系统等角度建立相关的翻译理论,研究相关的翻译实践,中心在“目标语文化”(target culture)而不是“源语文化”(source culture)。在这一模式中,译者的主体性更为彰显,翻译是实现译者目的的路径,重心在目标语文本受众(receptor)、目标语文化。如果存在目标语文化、目标语读者接受的问题,译者可作较大的翻译方法、技巧的调整。黄必康[16]采用了仿宋词的模式翻译莎士比亚的十四行诗,应该算是“翻译操纵派”理论的较好应用。试看黄必康教授对莎翁的著名第18首十四行诗的翻译。

例8:

原文:

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May.

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date;

Sometimes too hot the eyes of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimm’d,

And every fair from fair sometimes declines,

By chance or nature’s changing course untrimmed:

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st,

Nor shall Death brag thou wand’rest in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st.

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

译文(黄必康翻译):

夏日晴馥,

怎堪比,吾友俊秀雍睦。

五月娇蕊,

疾风过,落英纷纷簌簌。

夏景须臾,艳阳似火,忽又云遮路。造化恒变,

磋叹美色不驻。

唯君盛夏常青,

更红颜天成,雍华容禄。

笑问死灵,冥影暗,

奈何人间乐福?

君生无老,偕诗同向远,与时久夙。

天地不灭,

吾诗君生永驻。

第18首十四行诗表现的是莎士比亚对时间给人的美丽带来的摧毁性力量的感叹。这首诗叙述了友人的美丽在天地、季节、大自然面前处于被支配的地位。五月在英国是一个阳光明媚的月份,然而美好的时光总是匆匆而过,友人的美丽在自然力量的“折磨”中凋谢。诗人希望将友人的美丽俊秀凝固在五月这个美好的季节,于是诗歌的永恒造就了友人美丽外表的永恒,这种永恒在读者看来是内外兼修的永恒。可见,我们不妨将这首十四行诗看作一个叙事文本,其中的主人翁为“友人”“我”(诗人);这是个人叙事,叙述的是友人容貌的变化,但由于人人都有朋友,诗人所描述的友人容貌的变化在读者看来也存在,因此也是公共叙事。这首诗的元叙事是“诗化的美丽”(poetic beauty),具有普遍、可传承的意义。

黄必康教授的中文翻译仿造宋词,通过“吾友”“君”“吾诗”等三大主角树立了古风古色的意境,让读者将诗中所叙述的情景移植到中国古代,是“再语境化”(re-contextualization)的体现。通过骈文结构,将汉语翻译的古文写作风格加以显现,如“夏日晴馥,怎堪比,吾友俊秀雍睦”与“五月娇蕊,疾风过,落英纷纷簌簌”形成排比、对称的句法结构。通过“修辞问句+评论”的写作方式再现宋词的文风,如“奈何人间乐福?君生无老,偕诗同向远,与时久夙。”上述译文并未遵循原文诗歌的形式特征。译者基于自己对汉语驾驭自如的角度,站在目标语文化、目标语文本读者的位置上,对源语文本进行的“改写”,译者操纵痕迹明显。我们可把这种做法称为“操纵性叙事翻译模式”,并应用于中国少数民族文化宣传的英译中。试看下例:

例9:侗族的居住环境大多依山傍水,村寨都建于溪河旁、田坝中、或山脚下,寨中鼓楼耸峙,村边古树浓荫,花桥横跨流水,风景非常优美,侗族大都居住木楼。房屋属“上栋下宇”式木房。一般用三根或五根主柱串穿成排,将三排或五排相对竖立,再穿枋连成架。侗寨多建鼓楼。鼓楼是侗族村寨的独特标志,是侗族群众集会议事的中心场所。节日集会,鼓楼又是对唱大歌的地方。一般,一个族姓建一座鼓楼,有的村寨有四五个族姓,就要建四五座鼓楼。侗族的长廊风雨桥和花桥也是民族传统建筑艺术中的瑰宝。风雨桥多建于远离村寨的溪河之上,不仅给侗寨增添风采,也取村寨吉祥之意。

参考译文:Most Dong people live beside mountains and waters. The Dong’s villages are typically located beside rivers, between farm fields, or at the foot of mountains. There stand Drum Towers and age-old trees; there bridges for Dong’s entertainment (called Hua bridges) stride across creeks or rivers. Drum towers, feature bridges and cottages form beautiful scenery. Particularly should be mentioned Dong’s architecture. The residence houses are characterized with traditional Chinese construction skills. Wood and tile are the main materials; beams are joined together, and three or five pillars are connected in a row, standing as an interconnected framework. Drum Towers are common scenes in Dong’s villages. They are unique Dong’s constructions for collective meetings. At festivals the Grand Song is performed there. Generally speaking, each clan or surname has a Drum Tower, and hence in a village with four to five surnames there should be four to five Drum Towers. The long-corridor roofed bridge (called Fengyu bridge) and the bridge for entertainment are treasures of ethnic architecture. Fengyu bridges mostly lie on rivers away from villages, adding special charms to tourists and symbolizing fortune and luck to the villagers.

例9提及“上栋下宇”式木房。这一建筑具有中国文化特征,是典型的传统建筑艺术。源语文本针对的读者是中国读者,作者假设他们大都了解这类提法。但西方读者则不然。因此,在译文中加上The residence houses are characterized with traditional Chinese construction skills一句,目的是让目标语文本读者理解侗族是中华民族的一员,其建筑艺术也体现了中华大家庭的建筑特色。应该说,这一增加的表达在译文中起着画龙点睛的作用,是译者态度的介入,这是叙事翻译视角中的“元叙事”的体现。这一模式可用下图表示:

图2表明:1)在中国少数民族文化宣传汉译英过程中,译者必须兼顾源语文本与目标语文本,因此其身份具有双重性,既是源语文本的译者,也是目标语文本的作者。这种关系是双向式的,即源语文本、目标语文本对译者兼作者产生内容、信息安排、语言表述的影响,译者兼作者也掌握着源语文本、目标语文本的内容、信息、语言形态生成。2)译者通过与源语文本、源语文本作者的对话以及和目标语文本读者的对话,在目标语文本的信息组合和安排、翻译策略与技巧等方面加以“操纵”,在这一过程中,源语文本读者的作用可以放置第二位置,不做重点考虑。3)各翻译技巧的最终目的是彰显“元叙事”,即译者作为“叙事者”需体现文本主题或精神。以例9为例,该译文的“元叙事”就是“作为中华民族建筑艺术家庭一员的侗族建筑艺术”。据此,在译文的最后,对原文的“风雨桥多建于远离村寨的溪河之上,不仅给侗寨增添风采,也取村寨吉祥之意”在信息上作了处理,改为“这样的建筑对游客来讲增加了特殊魅力,对村民来讲象征财富与吉祥”(Fengyu bridges mostly lie on rivers away from villages, adding special charms to tourists and symbolizing fortune and luck to the villagers)。这一翻译策略与技巧的应用使得目标语文本的信息更为明晰,符合操纵理论的“明晰化准则”(rule of explicitness)。可见,相对于“加注式叙事翻译模式”,这一模式在中国少数民族文化汉译英过程中赋予了译者更大的自主性,使得公共叙事、元叙事得以更为完善地表现出来。

图2 操纵性叙事翻译模式

与“加注式叙事翻译模式”相比较而言,“操纵性叙事翻译模式”突显的是元叙事,所谓的公共叙事、个人叙事的采用、所占比例皆围绕元叙事而展开。试看例10的翻译:

例10:姊妹节是苗族娱乐性节日。流行于黔东南苗族侗族自治州台江、施秉、黄平等县。黄平县、施秉县过节的时间是每年农历二月十五,而台江县则是三月十五。苗语叫“浓嘎良”。节日以青年女子为中心,以邀约情人一起游方对歌、吃姊妹饭、跳芦笙木鼓舞、互赠信物、订立婚约等为主要活动内容。最具代表性和影响力的是施洞地区的姊妹节,时间是每年农历三月十三日至十六日。十三日,各村寨的姊妹们都上山去采撷木叶、姊妹花等花草树叶,制作黑、红、黄、蓝、白五色糯米饭。十四日下田捕鱼捞虾,凑钱购买鸭、肉、蛋等,于某家摆设“姊妹餐”宴请外房族的小伙子。十五、十六日是节日的高潮。白天,姊妹们梳妆打扮,穿上漂亮的衣裙,佩戴华丽的银饰与小伙子在笙鼓场上跳芦笙木鼓舞;晚上,男男女女相聚于游方场上对唱情歌,谈情说爱。节日结束后,姊妹们用竹篮盛装五色糯米饭,饭里藏匿松针、椿芽、辣椒等爱情标识,把自己的心思传达给男子。苗族姊妹节已列入第一批国家级非物质文化遗产名录。

参考译文:Sisters’ Festival is an entertainment festival for the Miao people, called Nong Ga Liang in the Miao language, popular in Taijiang, Shibing and Huangping Counties of Qiandongnan Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture of Guizhou Province. In Huangping and Shibing Counties the festival is held on lunar February 15 while in Taijiang County on lunar March 15. The Chinese Xinhua News Agency reported on April 19 (lunar March 15), 2019 that thousands of Miao people sing antiphonal songs as a way of celebration in Taijiang County, Guizhou Province. The size of participation is spectacular indeed. Young women are the center of the festival, and the activities include inviting lovers for singing duet (You Fang), eating Sisters’ Rice, dancing to the accompaniment of Lusheng and wooden drum, exchanging gifts as love tokens, and making engagements of marriage. The most influential Sisters’ Festival is observed in Shidong area from lunar March 13 to 16. On this occasion the young women of each village would collect leaves and Sisters’ Flowers, and make sticky rice in 5 colors—black, red, yellow, blue and white. On the 14thpeople would go to the fields for fish and shrimps, raise money for duck, pork and eggs, and set a “Sisters’ Meal” for young men of other clans. The 15thand 16thare the peak times. In the daytime the Sisters would dress up at their best, wear splendid silver ornaments and dance with young men at the Lusheng and drum site to the accompaniment of Lusheng and wooden drum; at night men and women would gather at the You Fang site for singing duet and dating. After the festival is over, the Sisters would hold the colorful sticky rice in bamboo baskets, with pine needles, Chinese toon sprouts and chili inside as tokens of love, and send it to their attached men. According to Chinese ethnologists and other international scholars, this festival embodies strong flavors of inherited customs and striking ethnic notions of love and marriage, hence regarded as “Oriental Valentine’s Day”. Miao, an important component of the Chinese people, have exerted much impact on the domestic and international stages due to their distribution in and outside China, and naturally Sisters’ Festival has been listed as one of the first national intangible cultural heritages. The following two pictures show a clear sign of how the festival looks like, judging from the girls’ dressing and the women’s active participation in making colorful sticky rice. Also, they reveal the dominating role of Miao women in social life, thus a window of vestiges of matriarchal society passed down from generation to generation.

Picture 1 Miao girls in splendid costumes on Sisters’ Day(Source:https://baike.so.com/doc/5706844-5919563.html)[17]

Picture 2 Miao women making colorful sticky rice on Sisters’ Day(Source:https://baike.so.com/doc/5706844-5919563.html)[17]

上述译文包括了公共叙事、个人叙事、元叙事。公共叙事主要是对节日的描述,个人叙事为译者插入的观点,是对节日盛况的评议,而元叙事则是通过民俗学家等专家的观点揭示节日的意义与影响。两张图片可看作个人叙事、公共叙事兼有。一方面,图片展现的是某位摄影者的报道与视角。另外一方面,摄影者也代表了在场的旁观者的视角,甚至是未到场的读者的视角,典型画面能从多模态的层面揭示该节日的过程。表1显示了例10译文的个人叙事、公共叙事、元叙事的具体体现和意义:

表1苗族姊妹节的叙事翻译

公共叙事

具体体现:

1.Sisters’ Festival is an entertainment festival for the Miao people, called Nong Ga Liang in the Miao language, popular in Taijiang, Shibing and Huangping Counties of Qiandongnan Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture of Guizhou Province. In Huangping and Shibing Counties the festival is held on lunar February 15 while in Taijiang County on lunar March 15.

2.Young women are the center of the festival, and the activities include inviting lovers for singing duet (You Fang), eating Sisters’ Rice, dancing to the accompaniment of Lusheng and wooden drum, exchanging gifts as love tokens, and making engagements of marriage. The most influential Sisters’ Festival is observed in Shidong area from lunar March 13 to 16. On this occasion the young women of each village would collect leaves and Sisters’ Flowers, and make sticky rice in 5 colors—black, red, yellow, blue and white. On the 14thpeople would go to the fields for fish and shrimps, raise money for duck, pork and eggs, and set a “Sisters’ Meal” for young men of other clans. The 15thand 16thare the peak times. In the daytime the Sisters would dress up at their best, wear splendid silver ornaments and dance with young men at the Lusheng and drum site to the accompaniment of Lusheng and wooden drum; at night men and women would gather at the You Fang site for singing duet and dating. After the festival is over, the Sisters would hold the colorful sticky rice in bamboo baskets, with pine needles, Chinese toon sprouts and chili inside as tokens of love, and send it to their attached men.

意义:

1.事件过程陈述。

2.客观面的呈现。

3.目标语文本的主要内容。

元叙事

具体体现:

According to Chinese ethnologists and other international scholars, this festival embodies strong flavors of inherited customs and striking ethnic notions of love and marriage, hence regarded as “Oriental Valentine’s Day”. Miao, an important component of the Chinese people, have exerted much impact on the domestic and international stages due to their distribution in and outside China, and naturally Sisters’ Festival has been listed as one of the first national intangible cultural heritages.

意义:

1.专家对民族节日的专业性解读。

2.揭示节日的民俗意义。

3.与目标语读者的交流、互动。

从译文中,我们不难发现,个人叙事、元叙事在源语文本中没有明确体现出来,往往需要译者增添信息,信息来源于相关可靠的研究、报道等。如,个人叙事搬出了新华社的报道[18]:

4月19日在台江县翁你河畔拍摄的苗族姊妹节对唱活动现场。当日,贵州省黔东南苗族侗族自治州台江县万名苗族同胞欢聚翁你河畔,以传统对唱的方式欢庆苗族姊妹节。

新华社是中国的官方新闻媒体机构,其可信度高,因而译者的声音、与读者的互动、主体性更好地加以体现了。

元叙事通过中国民族学家和国际学者的观点,展现了苗族姊妹节的民俗意义、国际影响以及列为中国第一批国家级非物质文化遗产的合理性。两张图片可让目标语读者进一步了解节日的盛况,对节日的主题有较好的烘托作用,直观地表现了节日对游客的吸引力。

苗族姊妹节是苗族重要的节日,其历史悠久,参与面大,影响力强,每年都要举行,这方面的资料、图片较为丰富。译者不必受到源语文本的内容繁简、格式的状况的限制,为了能够更好地展现这一节日的盛况、意义,译者可从内容、格式上加以操纵,可融入多方面的观点。也就是说,源语文本的性质可为译者作用的发挥提供较大的空间。

叙事存在各种体裁的文本中,也就是说叙事存在于描写、论述、说明文中,叙事翻译模式适合于各种体裁的文本中。相比较而言,它更适用于故事情节较强或有一定故事情节的源语文本,如民族介绍、节日、民俗、故事等。试看下例:

例11:“查白”歌节,是布依族人民的重大节日之一。这个节日起源于布依族民间故事。据传说,有一对布依族青年男女查郎和白妹,在劳动中建立了真挚的爱情,贪婪的财主抢走了聪明的白妹,害死了朴实善良的查郎,白妹悲愤交集,放火烧毁财主大院,并跳入烈火,以身殉情。多少世纪以来,每年农历六月二十一日就成了布依族人民的“查白”歌节。每年这天,黔、桂、滇三省边界的布依族青年男女,从四面八方聚集在兴义市一个叫作查白的地方,唱山歌,吹木叶,弹月琴,赛歌,以期在歌会上找到意中人。

参考译文:Chabai Singing Festival is a significant Buyi holiday, dated back to a folk tale. Once upon a time, a lad named Chalang and a lass named Baimei, fell in deep love in the course of living and work. Yet, fate played a practical joke on this couple. The girl was snatched away by a lusty landlord, and worse still her boyfriend, kind and honest was tortured to death by the evil landlord. Confronted with such a heavy blow, she set the landlord’s house compound on fire, and jumped into the flames, sacrificing her life for her beloved. For many centuries, the tale has been circulating in the Buyi areas on the border of Guizhou, Guangxi and Yunnan. In memory of the fidelity of the couple, Chabai (a blend of the names of the young couple) Singing Festival is held in Chabai (named after the young couple) of Xingyi City every lunar June 21, where people sing folk songs, and play the local Muye mouth-organ and the Yueqin fiddle. Sometimes, young people could find their attached dating partners there.

例11译文使用的是“加注式叙事翻译模式”,体现在:(1) Chabai (a blend of the names of the young couple) Singing Festival(“查白”作为节日是“查郎”和“白妹”名字的首字缩写);(2)Chabai (named after the young couple) of Xingyi City(“查白”作为一个地名也是“查郎”和“白妹”名字的首字缩写)。这一加注也显示了这对青年恋人在歌节中的重要性,是故事的主角,通过这两个主角故事加以展开,节日的民俗意义得到了体现。

例12:“吃新节”是贵州各地仡佬族的传统节日,多在农历七月初七举行,有少数地区在农历六月初六。在贵州仡佬族中流传这样一则神话,说谷种是狗随仡佬族祖先到天上去取谷种,由于祖先的被天神扣押,狗不得已,只有用自己的尾巴悄悄把谷种带到人间,从此人类才开始有谷种种植。“吃新节”是以祭祀祖先和自然神为主要特征的节日,主要通过祈神、娱神,来达到祈求风调雨顺,五谷丰登的意愿。

参考译文:Eating New-harvest Festival is a traditional Gelao people’s festival in Guizhou, held mostly on lunar July 7 or 6. The holiday is much related to a legend among the Gelao people. Once upon a time, a dog went to the Heaven with his Gelao owner in order to steal grain seeds. Yet, their intention was seen through by the Heavenly Gods, and the Gelao ancestor was arrested. Fortunately, the dog, which had the grain seeds hidden in its tail, was set free. The stolen grain seeds then brought about harvest after harvest to the human world. Eating New-harvest Festival is a holiday devoted to the sacrifice to ancestors and Nature Gods, which is meant to bless human beings with favorable weather and bumper harvest through sacrifice to gods.

例12告诉读者贵州仡佬族的“吃新节”的来历,通过故事的方式说明了上天种子到达人间的不平凡经历,彰显了仡佬族祖先及其饲养的狗的神勇行为与品德。译文采取了典型的英文故事陈述的方式once upon a time,是译者操纵的结果。Hasan[19]50-72认为,各种语类或体裁(genre)具有“必要成分”(compulsory elements)以及“选择性成分”(optional elements)。叙事中将时间、地点、人物、行为、结果甚至寓意列为必要成分,是由必要的,符合故事发展脉络。例7译文将故事类型的语类潜势(generic structural potential)发挥得较为淋漓尽致,让目标语读者了解到“吃新节”的民俗来源,较强的故事性增加了译文的吸引力,对于推动中国少数民族文化对外宣传具有积极意义。

例13:六月六是布依族、水族、土家族等民族传统节日。流行于广大少数民族地区。布依族称之为“六月场”“过小年”“关秧门节”“敬盘古”等,水族称“六月六”为“卯节”。布依族多在夏历六月十六或二十六日过节。届时,家家杀猪宰牛,包粽子供奉祖先、祭盘古。有的还杀狗庆贺。有的用白纸制作三角形小旗,沾上鸡血或猪血,插到田里,谓可免除蝗灾。岑巩县注溪乡对的土家族儿童则云集乡场,尽情游玩,各种适当要求也能得到满足。榕江县仁里、料理、桥桑等地的水族则在六月初五这天打扫门庭院落,包粽子和备节日食用的各种菜、糯米饭等迎接客人的到来。独山县基长一带的水族则要到羊场温泉洗澡。高峰时期可达三四千人。洗澡节活动有舀“神水”、洗澡、对歌。

参考译文:Liuyueliu is a traditional festival of the Buyi, Shui and Tujia people, popular in many minority areas. Liuyueliu is called by the Buyi people as “Liuyuechang” (Lunar June Occasion), “Guo Xiaonian” (Celebrating Small New Year), “Guanyangmen Jie” (Rice Seedling Transplanting Completion Festival) and “Jing Pangu” (Worshiping King Pangu), while the Shui people refer to it as “Maojie” (Mao Festival). The Buyi people tend to celebrate it on lunar June 16 or 26. On this occasion pigs and oxen are slaughtered and Zongzi (sticky rice wrapped in bamboo leaves for steaming until edible, a traditional Chinese festival food) (Chinese rice pudding) is made to worship ancestors and King Pangu. In some homes dogs are killed for celebration. Some people make triangle-shaped banners with white paper, smear them with chicken or pig blood, and plant them inside the croplands, which are supposed to keep off grasshopper attacks. In Duidi of Zhuxi Township, Cengong County, the Tujia children gather at some sites for joys and their demands can be satisfied as much as possible. On lunar June 5 the Shui people of Renli, Liaoli and Qiaosang of Rongjiang County clean their courtyards, make Zongzi, and prepare all sorts of dishes and sticky rice so as to greet the guests. The Shui people of Jichang of Dushan County would have hot-spring baths in Yangchang on this day. There can be as many as 3000 to 4000 bathers, and the activities for bathing include getting “holy water”, having a bath and singing a duet.

例13指出“六月六”是多个少数民族的具有特色的节日。叙事体现在节日中活动的安排上。译文采取了“加注式叙事翻译模式”,把“六月六”的不同称呼用“拼音+意义解释”模式加以呈现,如:“Guo Xiaonian” (Celebrating Small New Year)、“Guanyangmen Jie” (Rice Seedling Transplanting Completion Festival)、(Worshiping King Pangu)。虽然原文及译文似乎描写成分较多,但因为具有时间、地点、人物、活动、寓意等故事体裁的叙事成分,因而叙事性较强。

例14:侗族是中华民族中具有悠久历史的一个民族,来源于古“百越”族系,由秦汉时期西瓯中的一支发展而来。侗族主要分布黔湘桂鄂四省(区)毗邻地方。在封建王朝统治以前,侗族每个氏族或村寨,皆由“长老”或“乡老”主持事务,通过侗款,利用习惯法维持社会秩序,这种组织一直保存到19世纪20年代初期。侗族居住地,史称为“溪峒”,四周山峦,内有平坝,坝上溪水环流,平坝土壤肥沃,大者万余亩,小者数百亩。侗族文学艺术丰富多彩,有“诗的家乡,歌的海洋”之称。诗歌格律严谨,韵韵相扣,句句相映,比喻贴切,具有很强的艺术感染力。情歌优美,真挚热情;叙事歌委婉曲折,含义深长,可连唱数夜;歌词多以人类起源、民族迁徙和夫妻相爱、男女相恋为题材,具有史料价值;流传故事曲折,引人入胜。音乐曲调宛转悠扬。琵琶歌,因以琵琶或加“格以琴”(俗称牛罢脚)伴奏而得名,曲调欢快流畅,为侗族所特有。一领众和、多声合唱的无乐器伴奏的侗族“大歌”,声音洪亮,气势磅礴,节奏自由,享有盛名。以演唱者和听众人数多而得名。主要流行于黔东南苗族侗族自治州黎平、榕江、从江等县的侗族聚居区。其特色是主旋律在低声部,高声部是附和、派生的。其特点是:无伴奏、无指挥。黔东南州歌舞团侗族大歌合唱队于1986年10月应邀在法国巴黎艺术节上演唱,被法国《解放报》誉为“最有魅力的复调音乐”。

参考译文:

As one of minority groups in China, Dong has a long history. And Dong people are descendants of Baiyue ethnicity who lived near the Guilin River in the Qin and Han Dynasties. Now Dong people mostly live on the borders between Guizhou, Hunan, Guangxi and Hubei Provinces. Before the establishment of feudalism, all daily affairs were ruled over by a prestigious elder in a Dong clan or village. According to the folk law, the elder, called as Zhanglao or Xianglao, would cope with affairs via Dong Kuan—regulations of the Dong.This system was not canceled until the early period of the Republic of China in 1912.

Xidong, the gathering place of Dong, is a flatland embraced by mountains, where there are flowing streams and fertile soil. The Dong flatlands vary in size. Specifically, the bigger one may be over ten thousandmu(1mu=1 000 square meters), while the smaller one is only several hundredmuin size.

Dong have always enjoyed the reputation of “Hometown of Poetry, Ocean of Songs”, because they have rich colorful literary and art works. The poetry is appealing since its rules and forms are precise and profound. Furthermore, love songs are beautiful and emotional while ballads are mellow and meaningful, which are long enough to sing for several days on end. And the themes of songs include origin of human beings, migration of minority people, conjugal love and affection between lovers.

Pipa song, peculiar with Dong, is named because of the accompaniment of lute (Pipa in Chinese pinyin) or Geyi lyre (a string instrument with bull-leg shape for Dong). With Geyi lyre accompanying, songs sound more cheerful and fluent. Another unique performance for Dong is the Grand Song, which is famous for harmony and vigor without accompaniment and conductors when more than several hundred local singers sing together. Interestingly, the bass of the chorus is responsible for the main rhyme, while the treble echo. In October 1986, the Grand Song Troupe of Guizhou’s Qiandongnan Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture was invited to have a performance in Paris Art Festival in France. The performance was hailed byLiberationas “the most enchanting polyphony”.

例14呈现了侗族的来源、居住环境、生活与劳动、艺术等特征,译文采用了“加注式叙事翻译模式”。译文的叙事模式表现在:(1)主人公清晰:侗族;(2)民族来源以及艺术表演特点的叙事特征明显;(3)括弧内的注释有助于目标语读者了解中国少数民族文化的丰富性,把握其真正的内涵,有助于表现元叙事特点。

五、叙事视角下的中国少数民族文化宣传汉译英的反思

叙事翻译模式为汉译英、英译汉提供了有趣的路径,扩展了译者的自主性。然而,应当清楚不是什么类型的源语文本在转化为目标语文本时都适合使用叙事翻译模式,即便是使用,也是有较大的局限性的。Gentzler[20]168-221探讨了莎士比亚(Shakespeare)的《哈姆雷特》(Hamlet)在中国的翻译与传播。众所周知,《哈姆雷特》是传播最为广泛的故事,很多读者可能没有读过该剧本,但对其中丹麦王子复仇的故事却是有所耳闻或能道出个所以然。《哈姆雷特》是莎士比亚根据丹麦故事编写的戏剧,在改编该故事时作者作了以下改变:1)增加戏剧人物,呈现戏剧人物的二重性(即正反人物);2)故事情节的多样性、变化性;3)聚焦关键人物性格的相互影响(如Ophelia对Hamlet的影响),表现在心理(如疯癫)、对事件的解析上。据此,《哈姆雷特》的外译文本呈现出多样性、多元性等特点,有丹麦版、挪威版、英国版,等等。在莎士比亚的《哈姆雷特》中,Ophelia(Hamlet的恋人)的“诚实”(honesty)与“美丽”(beauty)联系在一起。因为Ophelia外表漂亮,自然会吸引不少追求者(suitor),因此在该剧第三场中Hamlet对Ophelia说:“如果你是诚实的,就不应与美丽有所瓜葛”。Hamlet担心Ophelia会像其母亲做出有违女人贞洁之事。莎士比亚想表达以下元叙事:美丽≠真理,这与济慈在《希腊古瓮颂》所表达的主题不同:美丽=真理(Beauty is Truth, truth beauty)。《哈姆雷特》在中国的翻译与传播与梁启超、林纾、田汉等著名人物有关,经历了社会变革、改写、五四运动等阶段,译文与原文的关系更多地体现在形象上,而非语言、文体(语体)的忠诚上。如,林纾的《哈姆雷特》中文译文标题为《鬼召》(A Ghost’s Summons),表现的是哈姆雷特死去的父亲托梦的情形;林纾的译文还在故事情节上有所变化,体现在“戏剧中的戏剧”(play-within-the-play),旨在表现主人公的复杂心理。田汉是中华人民共和国国歌的词作者,他在翻译《哈姆雷特》为中文时采用了“话剧”(Huaju/spoken drama)而不是“戏曲”(Xiqu/melody theater)风格,中文剧本包括了歌曲、舞蹈甚至武术等内容。田汉的翻译超出了传统的翻译模式,引入了一种新型体裁(genre)。他的翻译方法可看作为“中国社会变革的催化剂”(catalyst for social change in China)。Gentzler认为,这种翻译方法可称为“译编”(transadaptation),即“翻译+改编”,也是一种“改写”(rewriting),服务于译者的意识形态。

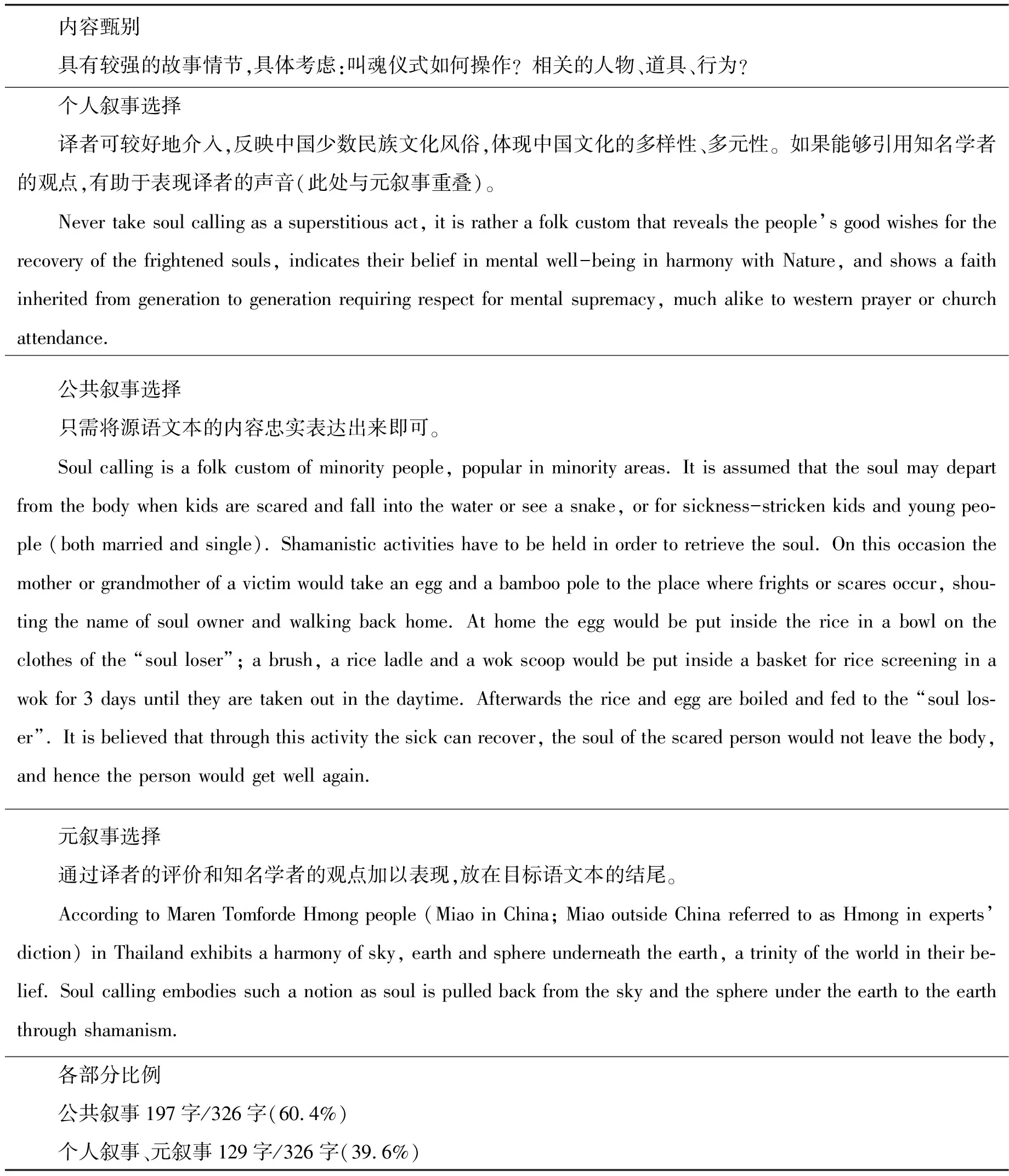

《哈姆雷特》在中国的翻译与传播为我国少数民族文化宣传的汉译英叙事翻译模式提供了借鉴,具体操作标准如下:1)甄别适合于叙事翻译模式的源语文本。一般来讲故事特征较强的文本较为合适,其他类型的源语文本要视情况而定,如某一部分使用叙事翻译模式,其他部分则按照功能等值模式操作。2)中国少数民族文化宣传的汉译英在当今的政治话语体系下应突显中华民族命运共同体的意识形态,应较为正面地宣传中国少数民族文化。3)译者个人声音(体现为源语文本中没有但在目标语文本中出现的内容,视为个人叙事)应与本主题相关,应为官方信息或可靠的媒体报道、学者研究成果,构成译者主体性的“互文性”(intertextuality)。换句话说,译者的态度、观点=学界、官方或民间的态度、观点。4)译者的个人声音所占比例不应为目标语文本内容的主体,即不能超过50%,否则会造成严重脱离源语文本的状况。

基于上述标准,我们可以看例15的汉译英:

例15:叫魂是少数民族民间习俗。他们认为,小孩受过惊吓如落水、遇见蛇等,或经常患病的小孩(以及一些年轻人,包括已婚、未婚的)等,其魂已不附体,要举行巫事把它叫回来。届时,由他们的母亲或祖母,在家中拿一枚鸡蛋、一根竹竿到受惊吓的地方,一边喊名字,一边往回走。到家后,把蛋放在碗中的米上,碗放在“掉魂”人的衣服上,把刷把、饭瓢、锅铲等放在滤米的簸箕内,簸箕放在锅中。一共放置3天,白天取出。米和蛋三天后煮给“掉魂”者吃。认为通过作用,病人才能恢复,受惊者的灵魂才不会离身,才不至于生病。

参考译文:Soul calling is a folk custom of minority people. It is assumed that the soul may depart from the body when kids are scared and fall into the water or see a snake, or for sickness-stricken kids and young people (both married and single). Shamanistic activities have to be held in order to retrieve the soul. On this occasion the mother or grandmother of a victim would take an egg and a bamboo pole to the place where frights or scares occur, shouting the name of soul owner and walking back home. At home the egg would be put inside the rice in a bowl on the clothes of the “soul loser”; a brush, a rice ladle and a wok scoop would be put inside a basket for rice screening in a wok for 3 days until they are taken out in the daytime. Afterwards the rice and egg are boiled and fed to the “soul loser”. It is believed that through this activity the sick can recover, the soul of the scared person would not leave the body, and hence the person would get well again. Never take soul calling as a superstitious act, it is rather a folk custom that reveals the people’s good wishes for the recovery of the frightened souls, indicates their belief in mental well-being in harmony with Nature, and shows a faith inherited from generation to generation requiring respect for mental supremacy, much alike to western prayer or church attendance. According to Maren Tomforde[21]154-155Hmong people (Miao in China; Miao outside China referred to as Hmong in experts’ diction) in Thailand exhibits a harmony of sky, earth and sphere underneath the earth, a trinity of the world in their belief. Soul calling embodies such a notion as soul is pulled back from the sky and the sphere under the earth to the earth through shamanism.

译文的最后部分增加了译者的评论,虽然占用的内容比例不多(不超过整体内容的50%),但十分重要,意思是:请不要将叫魂看作为一种迷信行为,它是一种民间风俗,揭示了人们希望受惊吓者能够康复的良好祝愿,说明人们认为心理上安康与自然和谐应为一致,显示这一信仰代代相传,要求尊重心理至上的理念,与西方的祈祷或教堂礼拜相似;相关专家的研究表明,泰国的苗族(祖先在中国)认为世界为天、地、地下三分,其信仰表现了三方面的和谐统一,因此叫魂体现了人们通过巫事希望“掉魂者”能恢复这种和谐,“掉魂”意味着和谐的破坏。该部分反映的是“个人叙事”,体现的是“元叙事”,有助于宣传中国政府尊重少数民族文化风俗的做法,同时通过提及叫魂类似西方宗教的祷告或教堂礼拜,以说明我国少数民族享有宗教自由。专家的观点进一步证实了中国少数民族的信仰的传承性以及文化生态性,具有较强的“互文性”。这里的“元叙事”为:宗教或民俗自由+天人合一的思想(汉族、少数民族皆有)。据此,例15的译文较好地体现了叙事翻译模式的基本要求。应当说,不管是“加注式叙事翻译模式”还是“操作性叙事翻译模式”,都应遵循上述三个标准。表2说明了叫魂仪式的叙事翻译模式操作程序:

表2 叫魂仪式的叙事翻译模式的程序

前文提到,叙事是个文学概念。文学作品中,叙事有利于突显人物形象:扁平人物 (flat figure)、圆形人物 (round figure)。扁平人物指的是文学作品里性格单一的人物,虽表现形式多样却没有统一,如“阿Q”,圆形人物性格多样但统一,如“王熙凤”。在叙事翻译模式中,人物形象的突显有利于表现“元叙事”。试看下例:

例16:六甲公是水族民间信仰。流行于黔南布依族苗族自治州三都水族自治县及周边水族地区。据说是《水书》的创造者。办丧事举行“开腔”敲牛、敲马时,念经的水书先生首先要举行仪式请“六甲公”来掌握礼规和时间。在请“六甲公”之前,要将房间打扫干净,在床上铺好新稻草和放上新被子,在死者棺材的右边用一个簸箕,放一尺白布、几穂谷子、几杯酒、几条鱼、一个银项圈、一双银手镯和六炷香等物,此时水书先生手持六吊谷子,口中念念有词,行迎接“六甲公”仪式。

参考译文:Mr. Liujia is a folk belief of the Shui people, popular in Sandu Shui Autonomous County and its neighboring Shui areas of Qiannan Buyi and Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Guizhou Province. Mr. Liujia (Liu Jia Gong) is said to be the founder of “Shui Scripts” (Shui people’s written characters and documents). At funeral services “mouth opening” is held for ox or horse knocking (a prelude of pleading Liu Jia Gong for appearing); at this time the master of Shui Scripts would first hold a ceremony to invite Liu Jia Gong to regulate the rituals and time concerned. Before Liu Jia Gong is invited, the room must be cleaned, and new rice stalk is placed on the bed along with a new blanket; on the right of the coffin of the dead is put a basket, with a 1-Chi (1 Chi=1/3 meter) piece of white cloth, a few ears of rice, several cups of wine, a handful of fish, a silver necklace, a pair of silver bracelets and six incenses inside it. The master of Shui Scripts holds 6 strings of rice, chants something and carries out the rituals of welcoming Liu Jia Gong. In the eyes of spectators and Shui people the master of Shui Scripts is the incarnate of Liu Jia Gong.

例16中的“六甲公”是水族的民间信仰,但也是《水书》的创始者,其贡献的认可是通过民间祭祀(此处为葬礼)来加以表现的。译文采取的模式主要是“加注式叙事翻译模式”,如:1)Mr. Liujia (Liu Jia Gong) (表明“六甲公”是个男性,也采取了拼音表达,旨在帮助目标语读者与源语读者的互动,使得前者能了解到后者的真实性别及具体称呼);2)“Shui Scripts” (Shui people’s written characters and documents)(括弧注释了水书为水族文字及相关文献,帮助目标语读者了解这一民族特色的文化负载词的真实含义);3)At funeral services “mouth opening” is held for ox or horse knocking (a prelude of pleading Liu Jia Gong for appearing)(括弧注释了“开腔”是请求六甲公现身的前奏,突出宗教祭祀的目的);4)1-Chi (1 Chi=1/3 meter)(括弧注释了中国的度量衡转换为西方度量衡的值,方便目标语读者理解)。译文在结尾也采取了“操纵性叙事模式”,加上了In the eyes of spectators and Shui people the master of Shui Scripts is the incarnate of Liu Jia Gong(在水族群众和旁观者看来,水书先生就是六甲公的化身),而此句原文中没有,目的是为了突出元叙事,这一手段也有助于体现六甲公或水书先生的“圆形人物”形象。六甲公是水族文字的创始人,也是水族的祖先崇拜对象,其形象可通过宗教祭祀或丧葬礼仪表现出来,也可在水书先生的一举一动中加以彰显,显示出六甲公的多样而统一的性格。

应当说,“扁平人物”和“圆形人物”这对文学概念在叙事翻译模式中并非表现得那么绝对分开,很多情况下它们是相互融合的,这一现象在少数民族节日文化宣传汉译英中尤为显著。试看下例:

例17:敬桥节是苗族祭祀性传统节日,流行于黔东南苗族侗族自治州苗族地区,时间在农历的“二月二”。祭品有鸡蛋、鸭蛋或鹅蛋以及糯米饭、腊肉、米酒、香烛之类。敬桥的目的主要在于祈求桥神保佑小孩无灾无难,而久婚不育的妇女则希望通过此举来祈求生儿育女。在三穗县寨头一带,“敬桥节”又被称为“禳桥节”。当地民众除了举行祭祀活动之外,还组织踩芦笙,唱情歌、斗牛、斗鸟、篮球比赛等娱乐活动。仪式体现了苗族人“修路补桥,有子保子,无子得子”的原始宗教观念。

参考译文:Bridge-worshiping Festival is a traditional festival of religious services of the Miao people, popular in the Miao areas of Qiandongnan Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture of Guizhou Province, normally celebrated on lunar February 2. The objects for services include chicken, duck and goose eggs, sticky rice, preserved pork, rice wine, incenses and candles. Bridge-worshiping is conducted mainly to pray to bridge gods for the peace and happiness of children, and the pregnancy of those women who have been infertile for a long time. In Zhaitou of Sansui County, Bridge-worshiping Festival is also known as “Bridge-deifying Festival”. On this occasion the local people would organize Lusheng blowing, love song singing, buffalo fight, bird fight and basketball games in addition to religious services. The rituals demonstrate the Miao’s primitive religious faith that “roads should be built and bridges repaired so as to bless those infertile women to have children while wishing the children other women to live long and happily”.

例17的译文与原文基本上对应,没有增加原文中缺少的内容,只是在译文中补充了On this occasion(在此场合),以说明节日活动的开展情况。因此,译文采取的是“加注式叙事翻译模式”。上述译文没有具体提及某人,但是突显了两类人物:妇女(包括久婚未育者以及有孩子者)、大众百姓。妇女和大众的观念相同:有子孙传承、子女平安。这种性格似乎是单一的,但由于祭祀活动的多样性、参与者的广泛性,人物的形象显得既有单一性(思想执着),也有多样性(不同参与者诉求有异),但又具有统一性(希望家庭传承、家庭平安)。看来,少数民族节日文化宣传的叙事汉译英体现的是“扁平人物”与“圆形人物”形象的混合性。

叙事翻译模式在当今民族文化旅游对外宣传中也能扮演重要角色。如:

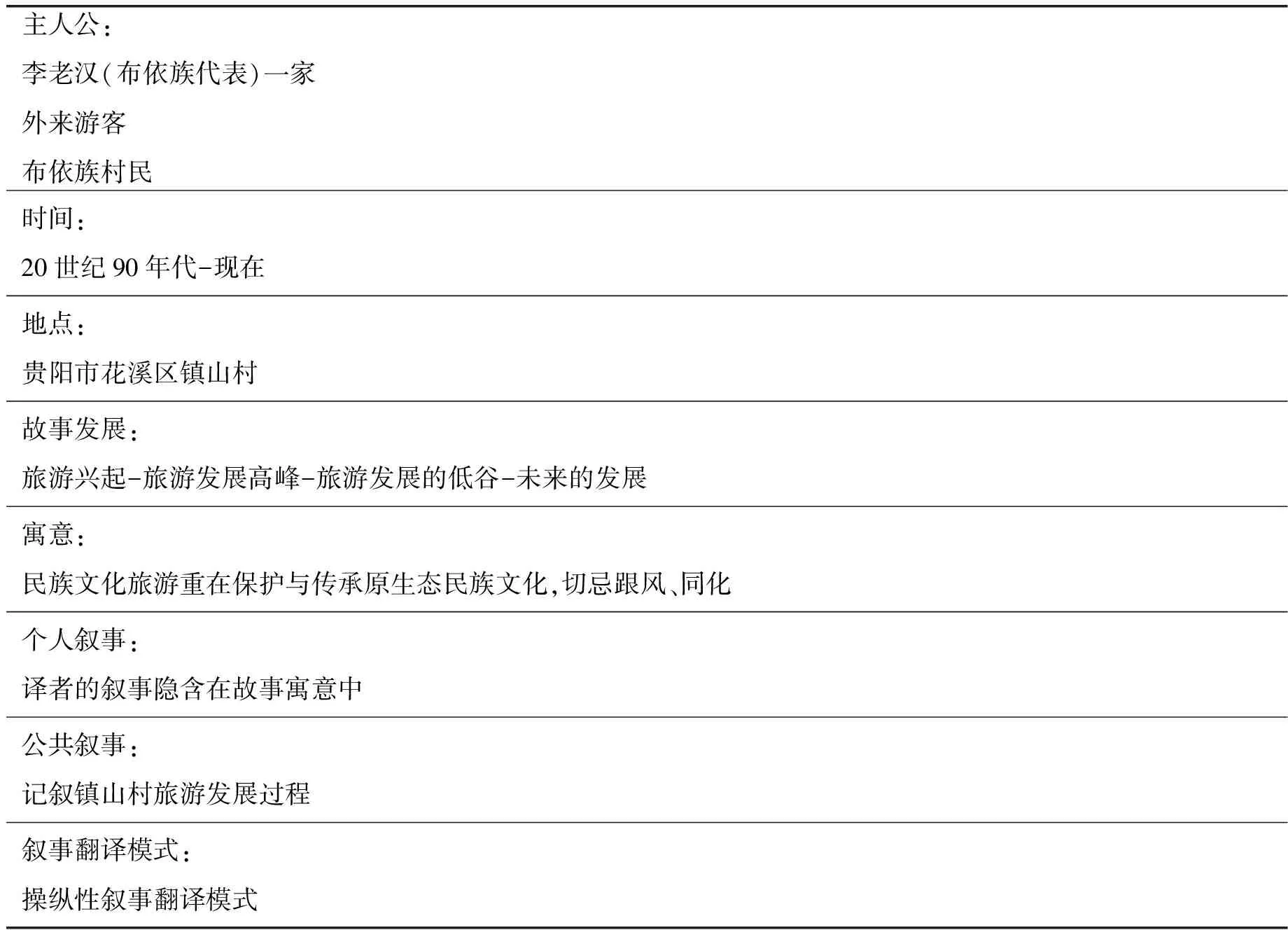

例18:镇山村的上寨远离水库,下寨靠近水库,有划船和烧烤活动,游客们更愿意到下寨来,所以下寨的农家乐和住宿要比上寨多得多,下寨的村民从旅游获得的收入显然要比上寨的村民要多。为了防止出现收入差距太大,村委采取了相应的办法,也就是将划船和烧烤的生意交给上寨的村民来经营,但毕竟来划船和烧烤的人没有到农家乐和住宿的人多,收入上的差距还是不可避免的。2005年之后镇山村的旅游呈现出下降的趋势,游客越来越少,尤其是在2010年之后下降得更为明显,收入也下降了,这与镇山村原生态的布依文化逐渐消失、旅游产业单一、还有周边旅游景区的兴起有关。现在到镇山村的游客比原来少了许多,显得比较冷清,以李老汉家为例,李老汉家的农家乐是在1993年开始的,到现在为止26年了,起初每年到他家吃饭、娱乐的人非常之多,名气相当大,当时他的妻子是做刺绣的,每次游客到李老汉家除了吃饭,还有参观刺绣、买刺绣等活动。李老汉家卖刺绣赚了不少钱,最贵的时候卖到了上千元一件。当时镇山村旅游发展特别好的时候,他家生意之火爆,连吃饭都要电话预定,而现在则要到门口去揽客。原来是一家人一起做的农家乐,但自从镇山旅游进入衰退时期,客人越来越少,家里的儿女因为客人少便到城里打工了。农家乐的生意由李老汉夫妇来经营,后来李老汉去世了,只好由妻子一个人来做,原先在庭院卖刺绣的情境再也一去不复返了。镇山村旅游开发的历程经历了初步发展时期、黄金发展期、衰退期三个时期。

经过多年来的旅游开发,镇山村的面貌发生了巨大的改变,旅游的人数越来越多,村民为了迎接旅游者的到来,把自家的房子装修成餐馆、茶楼等,有些家庭为了扩大旅游者的接待人数,将自己的家的房子增高两到三层,弄成小洋楼模样,有些家房子面积小达不到开农家乐的标准,便把自己家改装成商铺的形式向游客销售旅游商品和布依族特色的手工艺品等,在这样的情况下乡村民俗也发生相应的变化,主要体现在两个方面。一是自然的变迁,这种变迁是随着时代的变化和经济的发展而改变的,主要体现在衣食住行和婚丧嫁娶方面,旅游开发对乡村民俗变迁的影响较大,似乎是不可逆转的趋势或自然发展规律。二是被迫的变迁,即当地居民不得已改变自己的民俗以“迎合”经济发展。

镇山村是一个以布依族为主体的村寨,每逢重要的节日,都会有相关的节庆活动,如三月三、四月八、六月六(这三个节日为布依族节日)以及中国传统的节日等。布依族在这些节日里会有歌舞表演,还有众多的布依族特色美食呈现给食客,如五彩糯米饭和香肠腊肉等。村民会利用这样的节日来吸引游客。旅游开发使得某些传统的节庆活动发生了改变,譬如考虑到游客的需要,增加了一些新的仪式。在饮食方面,为了适应不同地方游客的口味,在布依族传统的菜肴制作方面做出了些改变,比如菜的盐味变淡些,或是增加些新的家常菜以满足游客的口味。在语言上,过去镇山村村民交流的主要媒介是布依语,但随着旅游业的发展,外来游客越来越多,村民不得不学习汉语以方便与游客沟通,时间长了,布依语在村中的交流与使用就变少了,除了少数上了年纪的人能说一些简单的布依话,在年青的一代人中,布依话俨然已成“外语”。 另外,镇山村的村民被汉化,失去了许多民族特色,游客的文化旅游动机减少,转而去其他旅游景区。因为这里的吃饭和娱乐项目在其他旅游景区同样能够满足,相比起来没有什么特色,到镇山村来不是到农家乐吃饭,就是去打麻将,丝毫感受不到原生态的布依族文化,游客对于没有文化特色的布依村寨不再感兴趣。

参考译文:Zhenshan Village is composed of the upper part and the lower part. The upper part is far from the reservoir while the lower part is close to it, which offers such activities as boating and barbecue and hence is a place where tourists enjoy visiting. As a result, there are more farmers’ accommodations in the lower part than in the upper part, and surely an income gap comes into being when tourism is involved, the former being richer than the latter. To reduce the income gap, the Village Committee took some measures; specifically the business of boating and barbecue is handed over to the upper part. Nevertheless, more people come for farmers’ accommodation than for boating and barbecuing, and hence the income difference is unavoidable. After 2005 tourism declined in Zhenshan Village with fewer and fewer visitors, which was particularly evident after 2010. As a consequence the income from tourism dropped, which is supposed to be related to the gradual disappearance of the indigenous Buyi culture in Zhenshan Village, the monotonous structure of tourism, and the emergence of nearby tour spots. Fewer tourists come to Zhenshan Village than before, which thus looks quite desolate. Take Senior Li for example. Mr. Li started a farmers’ accommodation in 1993, 26 years before now. In the beginning many people came to Mr. Li’s home for meals and entertainment, making it well-known near and far. Also, his wife did embroidery at that time. Whenever the tourists came, they would eat to their heart’s content and had a good time, and they also visited Mrs. Li’s embroidery and even bought some of her works. The Li’s family earned much from the sales of embroidery; the most expensive product could sell over 1000 yuan a piece. The then tourism was prosperous and so was Mr. Li’s business. Sometimes people had to make phone reservations for meals. It was totally different from now when most families have to attract customers themselves. The business used to be managed by the whole family, but since tourism in Zhenshan Village receded, there were fewer and fewer guests, and for a lack of guests and income Mr. Li’s son and daughter had to work outside in town. The farmers’ accommodation used to be operated by the Li couple, yet after Li died it had to be left to Mrs. Li alone. The scene of courtyard sales of embroidery is gone forever. The tourism development in Zhenshan Village went through three periods, namely, the initial, golden and recession periods.

It is pleasing to find that Zhenshan Village has taken on a new look after years’ tourism development. Due to an increasing number of tourists, some villagers decorated their houses into restaurants and teahouses, and to accommodate more guests some villagers even increased their house height by two to three floors, looking like western-style houses. Some houses are not spacious enough to meet the standard of farmers’ accommodation, and then the owners converted them into shops selling tourist products and Buyi handicrafts. Under these circumstances the local rural custom has changed, mainly reflected in two aspects. The first is related to natural transformation. In other words, the change happened with time and economic development, mainly revealed in food, clothing, funeral and marriage. Tourism development exerted much impact on local folk custom, which seems an irreversible trend or a natural development law. The second is that the farmers had to change their custom to “cater to” economic development.

Zhenshan Village is mainly a Buyi residence. At each important festival, such as lunar March 3, April 8 and June 6 (Buyi festivals) and traditional Chinese festivals, there are relevant celebrations. The Buyi people would put on singing and dancing shows and offer a variety of Buyi foods to the diners, for example, colorful sticky rice, sausage and preserved pork. The villagers make full use of these occasions to attract customers. Of course, tourism development has changed some traditional festival activities. For instance, considering the tourists’ needs, some new ceremonies were added. In diet some change has been made in traditional Buyi cuisine in order to meet the tastes of different customers, for instance, less salt in dishes or more homemade dishes. In language Buyi used to be the main medium of communication between the villagers, yet with tourism development and an increasing number of travelers, the farmers have to learn Chinese for communication with outsiders. As time goes on, the Buyi language is less used except for some elderly people who are able to say simple Buyi. For the young generation it has become a “foreign language”. Also, many villagers here have been sinicized and lost their ethnic features. This reduces the tourists’ cultural motivation and they turn to other scenic spots, where meals and entertainment are equally satisfied. There seems to be no special ethnic feature in Zhenshan Village except for food and Majiang game. The loss of indigenous Buyi cultural features drives many tourists away from the village.

上面的例子介绍了贵阳市花溪区镇山村旅游业发展的喜忧。故事的叙事部分表现在李老汉一家旅游发展的起起落落以及镇山村旅游发展对当地风俗习惯的正面和负面的影响。译文在叙述李老汉一家旅游业接待高峰期和低落期时采取了一般过去时,是叙事模式的基本特点。在描述外来游客对旅游收入的初期增加、初期的旅游繁荣以及风俗同化造成布依族民俗民风的消减和吸引力的减少时,译文采取了一般过去时、现在完成时、一般现在时三种时态,体现了旅游发展的过程以及相关影响。这些时态的使用是英语叙事模式的典型特征。在这个“操纵性叙事翻译模式”中,李老汉、外来游客、镇山村的布依族百姓是主人公,其形象与当今民族文化旅游所带来的机遇、造成的问题吻合。表3说明了这一叙事模式的特征:

表3 镇山村布依族文化旅游的叙事翻译模式

六、结语

Maestri[22] 145-182讨论了自传故事的翻译对于对话空间(dialogic space)和互文共鸣(intertextual resonances)的影响。根据Maestri的观点,故事讲述者未必遵循时间顺序。由于存在着多个故事空间,它们之间的界限不明,因而各故事之间的关联较为复杂。叙事过程的复杂性通过时间有序/无序、故事间关联清晰/模糊的特征来体现。鉴于此,对话空间呈现出流动、动态的特点。译者在故事翻译过程中必须考虑以上因素,理顺各个故事之间的关系,因而目标语文本会展现故事间互文共鸣的特征。互文共鸣在叙事翻译模式中还可通过个人叙事、元叙事加以表现。我们在此讨论的个人叙事为译者的观点插入或补充,其实个人叙事还包括故事中单个人物的故事讲述,本文引用的例子未涉及这点。

叙事翻译模式在中国少数民族文化宣传汉译英的过程中扮演着“对话窗口”(dialogue window)的角色,有助于更好地将中国优秀文化推向世界舞台。无疑,叙事翻译模式是对“功能等值论”“翻译文化转向”“翻译操纵论”的有力补充。本文对Mona Baker、Juliane House倡导的叙事翻译模式进行了进一步解读,提出了具体模式(加注式叙事翻译模式、操纵性叙事翻译模式)、操作程序(内容甄别、意识形态以及个人叙事、公共叙事、元叙事的表现、所占比例)等,丰富了跨文化交际翻译学理论与实践框架,是《跨文化交际翻译学:理论基础、原则与实践》的姊妹篇。我们还要另外撰写相关文章,从其他翻译路径进一步丰富跨文化交际翻译学的理论和实践框架。