羊肚菌子实体发育生物学(下)——生物学和非生物学因子对菌丝培养和子实体形成的影响

赵永昌 柴红梅 陈卫民 赵子悦 孔令舰

羊肚菌子实体发育生物学(下)——生物学和非生物学因子对菌丝培养和子实体形成的影响

赵永昌 柴红梅 陈卫民 赵子悦 孔令舰

(云南省农业科学院生物技术与种质资源研究所,云南 昆明 650221)

3 羊肚菌发育生物学

羊肚菌的生活史是研究的难点,目前有提出两种生活史[114, 115],都认为形成菌核和分生孢子是关键环节。储存营养的菌核在子囊果发育过程中作用较大,既可以萌发为生殖菌丝,又可以直接产生子囊果。羊肚菌的菌核为假菌核,不同的可栽培出菇的菌株产菌核能力差别较大,甚至有菌种阶段完全不产菌核的菌株也能很好地出菇;另一方面尚无菌核萌发成原基的直接证据。分生孢子的争议则较大,主要是从自然基质得到的分生孢子不能萌发,且羊肚菌产量与分生孢子产生量没有直接相关性。使用覆膜技术种植羊肚菌有的分生孢子非常少但出菇不受影响,用圆叶杨种植也几乎未发现有分生孢子形成。因此,羊肚菌的发育生物学基础研究可能是解决羊肚菌稳产、育种的关键,而实现室内稳定出菇则是研究的基础。解决羊肚菌培养过程中遗传的多变性是重中之重。

3.1 子囊孢子形成与萌发

子囊孢子的形成与萌发是羊肚菌发育的关键问题,羊肚菌子囊孢子具有多核现象,有的多达数十个核,这些核是同核体还是异核体尚不清楚。虽然有不少学者试图对羊肚菌子囊孢子的形成进行深入研究,但是由于未实现室内栽培,难以找到不同发育时期的子囊孢子个体,导致研究困难。陈立佼借助梯棱羊肚菌的大田栽培,通过细胞核染色技术对子囊孢子的形成进行研究,总结出子囊孢子形成的过程模式[116],说明羊肚菌子囊孢子的多核是孢子形成后的有丝分裂导致的,多核子囊孢子应是同核体,这方面的结果得到交配型基因鉴定证明。Chai等证明-20和子囊孢子群都是同核体,具有1-1和1-2交配型基因子囊孢子的比例与1˸1无偏差,所以M-20和是异宗结合的[117]。有研究认为栽培条件下子囊果形成孢子比较晚,自然生长的子囊果倾斜或倒伏状态时才会形成孢子,此时子囊内除孢子外基本呈透明状态,不存在其他细胞器或大分子。也有不形成孢子的共生类型的羊肚菌菌株[118]。

在室内条件下,羊肚菌的子囊孢子较易萌发,在湿度适宜时3小时就可见到芽管,因子囊孢子的多核性其可能从1-5端长出芽管萌发;在野外,影响子囊孢子萌发的因素很多,温度、湿度、营养条件都可能影响。研究表明,子囊孢子萌发对温度比较敏感,室内温度低至2 ℃都能萌发,但将孢子包埋在玻璃纸里放置在出菇点时,土壤温度超过10 ℃都不萌发。当土壤持续升温到15 ℃时会抑制子囊孢子的萌发,地表的孢子一年后将失去活力。将经灭菌的黑麦埋入地中,土壤温度保持在10 ℃以下时,无论孢子还是菌核都容易在其上定植[119]。一定浓度范围的MgSO4、KNO3、CaCl2、NaNO3对孢子萌发和菌丝生长有促进作用[120]。子囊孢子萌发的菌丝一般仍为多核体细胞,同一子囊孢子萌发得到的初生菌丝不发生融合,也未观察到不同子囊孢子萌发的菌丝之间发生融合[118, 121]。有研究表明,单孢菌株配对后能形成异核体,这与菌柄分离的菌株为异核体类似,间接表明其为异宗结合[114, 122, 123]。

3.2 多变的培养形态

羊肚菌的培养形态变异之大是目前大型真菌中少有的,相同培养条件下不同种或同种不同菌株在菌核形成的时间、形态、多少和大小等方面均有不同,在不同的培养条件下同一菌株菌核的产生和形态也不同,培养过程中的变化不仅类型多且重复性较差。虽然培养基组成、生长条件显著影响羊肚菌生长速度[124~129],但引起这些变化的原因是遗传性的还是纯粹生理性的尚不清楚。羊肚菌菌丝存在多核现象,这种多核仍旧是同核体。同核体菌株培养过程中变化稳定,不存在由于核丢失而产生变化。

陈立佼等从单孢群体出发以产菌核能力为定性特征研究了培养特性变化[130],单孢菌株按培养特征可分为9类(表3),同等条件下每一菌株的培养特性保持稳定,在综合马铃薯葡萄糖培养基(CPDA)、葡萄糖硝酸钠琼脂培养基(GN)、酵母膏胨葡萄糖琼脂培养基(YPD)进行转接培养时,可成功地将产菌核菌株转化为不产菌核菌株。同一子实体及不同子实体产菌核单孢菌株产核数量及分布,变化很大,对峙培养后单孢之间性状会发生较大变化,包括菌核形态、菌丝形态、生长势,特别是产菌核能力会消失和发生转移:①同一子实体单孢菌株之间存在拮抗作用,对峙培养时相互接触部位会形成交合线,出现浓密的生长区,将不产菌核的单孢菌株与同一子实体及不同子实体产菌核单孢菌株进行对峙培养,即使来自相同子实体的单孢菌株之间也会出现拮抗作用。拮抗线两侧的菌丝和亲本菌株相比形态和产核情况有很大变化,在各对峙组合中不同亲本的组合拮抗线情况不同。②在对峙组合中由于拮抗作用,两亲本的生长势不同,有拮抗的组合中产菌核菌株长势明显占优,只是有的长势处于弱势,可能是由于产菌核菌株菌丝辐射状快速生长,使其在平板上能迅速占据更多培养资源。③产菌核水平变化,拮抗作用对产菌核能力影响较大,有产核能力减弱的,有完全失去产菌核能力的,也有产菌核能力互换的(在组合中一个菌株将产菌核能力“转染”,原来产菌核的菌株仍然产菌核,不产菌核的菌株能产菌核),可推测在对峙培养过程中与菌核形成相关的遗传因子可在细胞间迁移,或是菌核产生与某种分泌物有关。该物质有一定的趋向性,各菌株对其吸引能力的强弱决定了它的分布,从而影响了菌核的产生和分布。

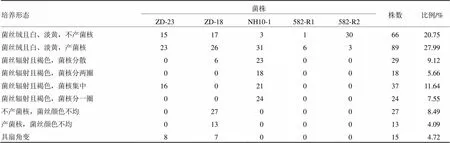

表3 基于YPD上的培养特征的羊肚菌单孢菌株分组[130]

3.3 菌核形成与变化

3.3.1 纯培养条件下菌核变化

菌核是一种由菌丝组织化形成的具有抵御逆境作用的致密菌丝结构,逆境是菌核产生的重要基础与条件;然而羊肚菌在营养丰富的环境中也能产生菌核。说明营养因素既可以刺激也可能抑制羊肚菌菌核的形成。尽管羊肚菌栽培取得了进展,但仍具有挑战性,因为即使按照专利也不能完全栽培出菇。多数研究认为,要获得栽培成功,必须获得菌核,不少人曾经将精力集中在菌核产生研究上。对于羊肚菌菌核的形态和形成过程有不同看法,Alvarado-Castillo等[131]的分类比较合理,包括七个阶段:①菌丝生长,②初级菌丝生长和分枝,③次级菌丝缠绕,④大量菌丝聚集,⑤菌丝聚合生长,⑥菌核形成,⑦菌核生长与成熟,成熟伴随厚垣孢子和分生孢子形成。

影响菌核形成的因素较多,包括环境因子和营养因子[71, 132],营养因子涉及种类和浓度。在不同蔗糖浓度的培养基上,菌丝生长速度、菌核颜色差别较大,且形成菌核的菌丝体外表会有一些具备储蓄能力的气泡[133, 134]。氮源的影响高于碳源[135],在含核糖、半乳糖、山梨糖和甘露醇的培养基上较难形成菌核,而NaNO3和酵母提取物有利于分散型菌核形成[136, 137]。复合营养物如玉米、小麦、燕麦和黑麦等,对菌核的形成有促进作用[138]。而饥饿可以诱导和增加假菌核的形成,假菌核中丙二醛含量增加与脂肪的过氧化和氧化压力有关[139]。影响菌核形成的非营养因素包括光照、温度、有机酸、环境腐败产物的积累、酚类化合物、多酚氧化酶活性、机械屏障、疏基修饰因子,以及渗透压等,能增加或减弱氧化应激的生长因子可能都有促进或抑制菌核分化的作用。

3.3.2 菌核生理变化

木质素降解酶是大型真菌最重要的酶之一,其参与人工栽培的子实体形成。在羊肚菌生活史中,菌核是羊肚菌从菌丝到子实体的中间态。研究表明,在不同培养基上,羊肚菌菌核形成过程中木质素降解酶的活性有较大变化,不同培养基上都产生漆酶(LAC)、木质素过氧化物酶(LiP)和锰过氧化物酶(MnP)等木质素降解酶,在麦粒培养基上LAC活性最高,而在谷壳培养基上则是MnP和LiP最高;在土壤复合培养基上,从菌核形成到成熟都能产生漆酶,都能测到漆酶活性[140, 141]。由于基质对菌核形成及相关酶分泌有诱导作用,所以羊肚菌栽培过程中栽培种配方的选择对菌核形成及后期胞外酶的表达有决定性作用。

3.3.3 菌核形成过程中基因表达变化

羊肚菌菌核形成能力的差异,表面上受环境因素影响,实际上是由菌株本身的遗传多样性决定的。Chen等[142]利用mRNA差异显示技术对同一子实体分离的在相同培养条件下得到的产菌核和不产菌核的羊肚菌单孢进行研究,得到了阳性的假设蛋白及未知的差异片段58个,其中26条片段为已知蛋白功能片段、9条与已知物种的假设蛋白编码片段相似,23条为未找到假设蛋白片段。这些片段对应的基因可能控制着羊肚菌产菌核与否或能力高低,为在遗传和基因调控水平研究羊肚菌产菌核的机理提供了重要的遗传信息。在确定功能的基因中,氨基丁酸通透酶片段、外膜家族蛋白相关蛋白片段和人类角蛋白结合蛋白片段都与羊肚菌逆境应激和结构适应性变化有关,即得到的差异片段与植物中的脂质代谢、氮代谢、逆境应激及细胞周期调控有关。这些片段可能是羊肚菌的氧化应激反应的上游诱导因子或下游产物,需要得到片段全长并进行更深入的功能研究才能确定。表明羊肚菌菌核形成能力可能更多地与菌株对外界环境适应性的遗传多样性有关。

3.3.4 菌核与子实体形成能力之间的关系

虽然最早的研究认为,菌核是羊肚菌生活史中最重要的阶段[9],易出菇的火烧地在两年内观测到的羊肚菌菌核比非火烧地多得多[143]。但对羊肚菌的生活环境调查研究发现,菌核并不是所有种的羊肚菌生活史的必须阶段,不同种在生活史的进化上有区别[71]。目前实验证明,菌核的有无与出菇与否及产量高低之间没有必然的联系,有菌核产生的菌株不一定出菇,很少形成菌核的菌株同样也可以出菇[144]。虽然在栽培实践中,多数种植者认为需要栽培种长满菌袋(瓶)并形成菌核后才可以播种,但不少菌丝长满后就播种的出菇时间缩短,且产量稳定。

3.4 分生孢子

羊肚菌栽培过程中会形成分生孢子,Ower[9]也有提及。分生孢子在目前假设的羊肚菌生活史中是重要的阶段。研究表明,羊肚菌分生孢子多数为单核[145],且产生与否与出菇与否无直接关系[144]。但也有认为分生孢子类似于植物花粉的作用,对出菇有重要的意义[146]。

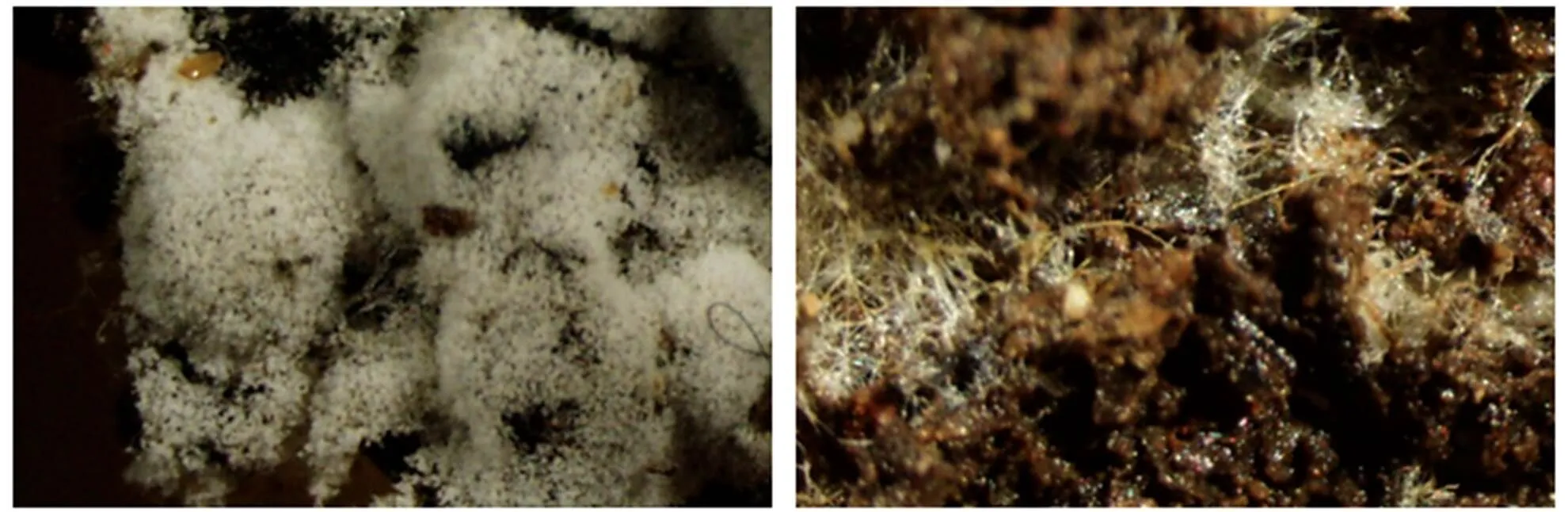

图2 羊肚菌产生分生孢子(左)与不产生分生孢子(右)

明确羊肚菌分生孢子的生物学功能,首先须解决无菌培养条件下分生孢子的形成和分生孢子的萌发两个难题。分生孢子可能是一种休眠体,其萌发需要特定的环境条件,目前尚无在栽培过程中观察到分生孢子萌发的报道。根据我们研究,在灭菌基质上生长的羊肚菌可以形成分生孢子(图2):①分生孢子形成与器皿无关,不同的器皿培养都能形成分生孢子;②分生孢子形成与接种量密切相关,当接种量大时不形成分生孢子;③分生孢子形成与温度相关,温度超过24 ℃,形成的分生孢子较少,而10~24 ℃间的差别不明显,但形成时间有差异;④在最优条件下,不同菌株分生孢子的产生量差别较大,同一物种分生孢子形成数量多孢菌株>单孢菌株>组织分离菌株;⑤分生孢子形成与土壤基质的颗粒度密切相关,颗粒度小分生孢子数量少。

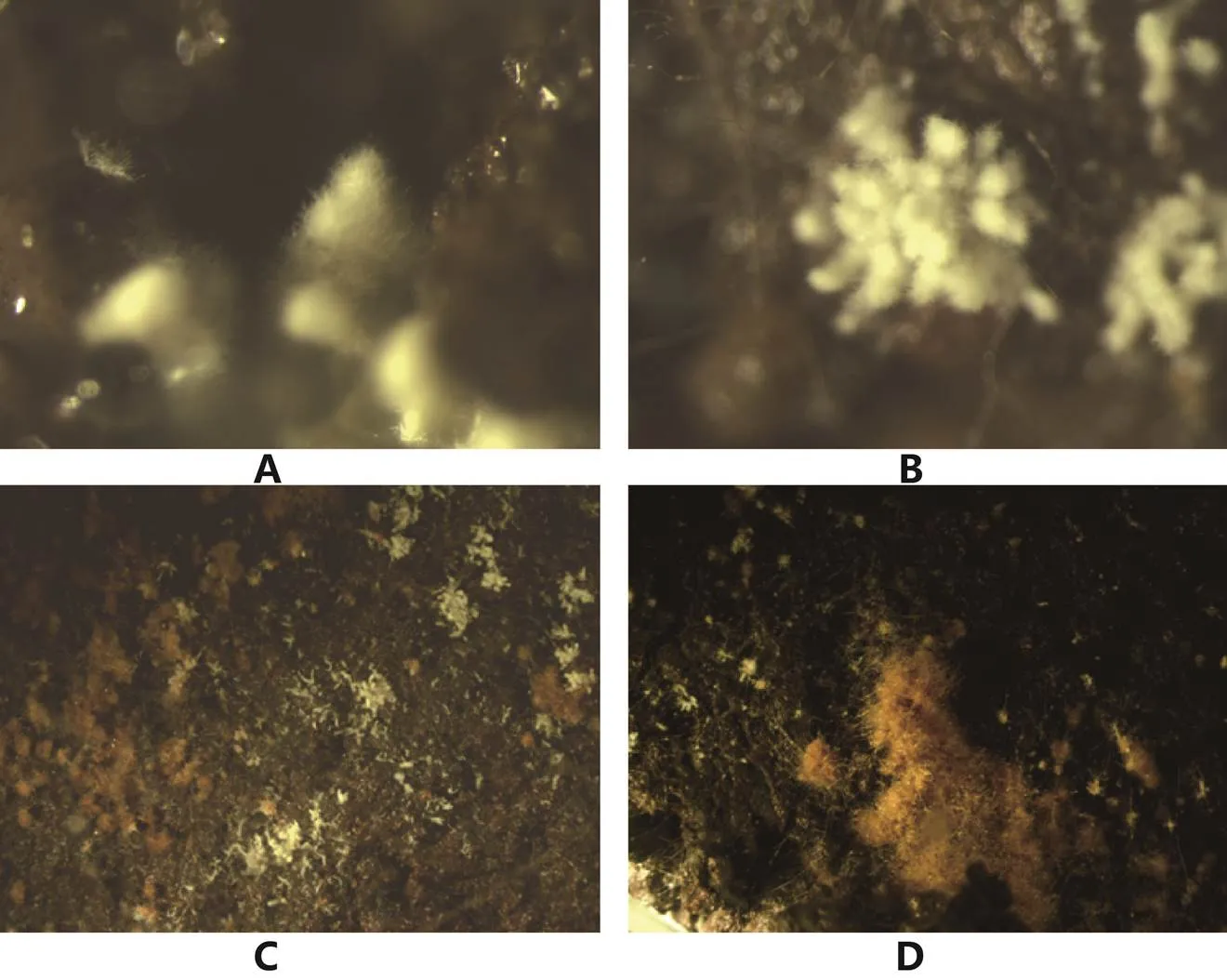

A:分散型原基;B:丛生型原基;C:分散性菌核周边的原基;D:大菌核周边的原基。

3.5 原基形成分化与子囊果形成

Ower[9]首次较为完整地描述了羊肚菌子实体,之后不断有人对羊肚菌发育过程进行描述[69,70,144],基本特征是在基质表面上从一个点逐步形成菌丝团,菌丝团上下组织化分化出菌盖和菌柄,菌柄往下生长吸收营养,菌盖往上发育逐步成熟。与其他菇类原基下面是密集的菌丝不同,大田中经常观察到羊肚菌原基是由一个小点形成的,羊肚菌子实体发育的营养是如何供给输送的尚不清楚。我们研究发现光温湿可控条件下原基可以形成(图3):①单一交配型的菌株都不能形成原基,不同物种多孢分离菌株和组织分离菌株在原基形成的形态和数量上有差异,但无规律;②原基形成的数量与分生孢子形成相关,没有分生孢子(包括接种量大、24 ℃培养)的都未形成原基;③虽然很难看到原基由菌核分化而来,但菌核多的原基数量多且密。虽然是初步结果,且在原基的分化和幼菇发育控制上尚需进一步研究,但结合大田的种植结果可以为羊肚菌优良菌株鉴定体系的建立奠定基础。

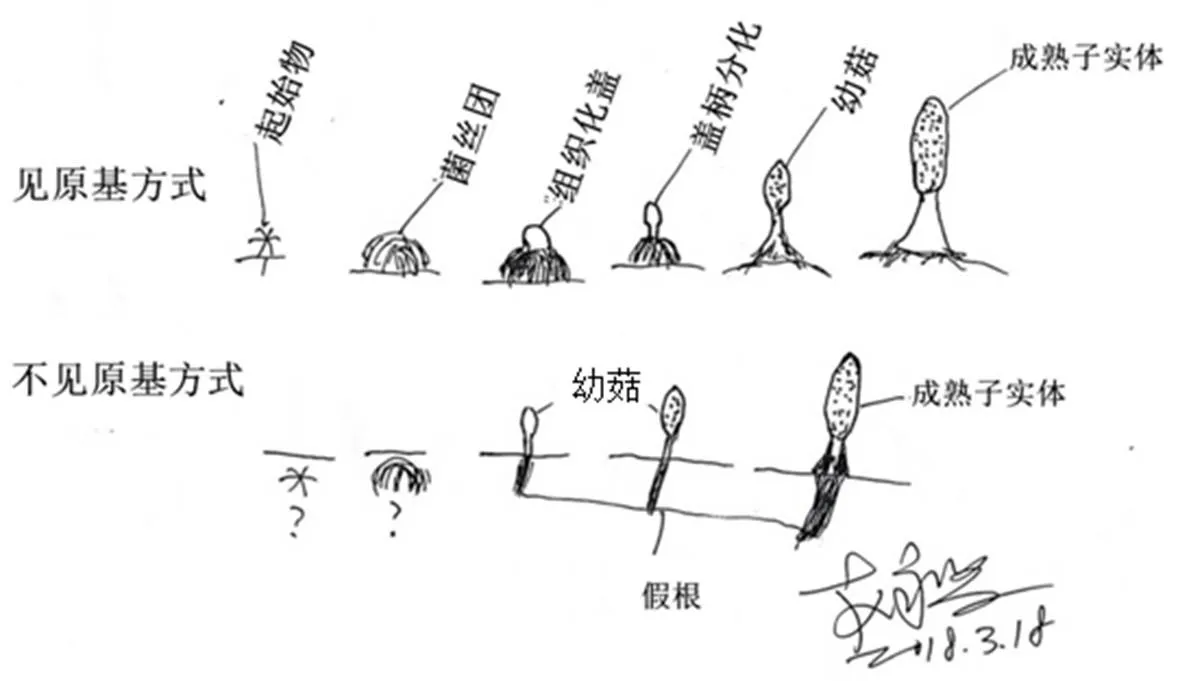

图4 羊肚菌栽培两种不同的出菇方式

3.6 出菇方式与富营养栽培

大田栽培羊肚菌出菇方式有见原基和不见原基两种(图4),有以下特点:①与菌株特性有关,多数菌株是见原基出菇,有的则易不见原基出菇,也有两种出菇形式都常见;②与土壤的酸碱度、颗粒大小、湿度等相关;③与栽培方式如覆土厚度相关;④不见原基出菇的成菇率高,但其发生率更低;⑤同一菌株同一田块两种出菇方式都会发生;⑥不见原基出菇往往伴随假根的形成(图5)。

图5 不见原基出菇形成的假根

图6 营养袋内形成的原基

两种出菇方式的机理尚不明确,对其研究有利于提高成菇率,可控制出菇的密度和整齐度。实现对不见原基出菇方式的控制更有利于实现工厂化栽培。不见原基出菇形成的假根应该是环境因素引起而不是物种的特点,不应作为分类依据。沙质土壤滴灌或喷灌易导致土壤微移动,这种土壤移动是“见原基出菇”方式中原基因移动而悬空死亡的重要原因,提高成菇率可在催菇后进行喷雾保湿。

工厂化栽培的难点是通过富营养栽培提高单位面积的产量。但富营养情况下较难出菇,在栽培中曾发现营养袋内形成大量原基(图6),提示条件适宜的情况下富营养栽培是可行的。

致谢 本文图5、图6由四川省平昌县金源生物科技有限公司孙胜先生提供,特此感谢。

[1] Sheikh PA, Dar GH, Dar WA, et al. Chemical Composition and Anti-oxidant activities of Some Edible Mushrooms of Western Himalayas of India[J]. International Journal of Plant Research, 2015, 28 (2): 124-133.

[2] Vieira V, Fernandes Â, Barros L, et al. WildPers. from different origins: a comparative study of nutritional and bioactive properties[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2016, 15, 96(1): 90-98.

[3] Nitha B, Fijesh PV, Janardhanan KK. Hepatoprotective activity of cultured mycelium of Morel mushroom,[J]. Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology, 2013, 65(1-2): 105-112.

[4] Hatanaka SI. A new amino acid isolated fromand related species[J]. Phytoehemistry, 1969, 8(7): 1305-1308.

[5] Tietel Z, Masaphy S. True morels (Morchella)—nutritional and phytochemical composition, health benefits and flavor: A review[J]. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2018, 58(11): 1888-1901.

[6] Tietel Z, Masaphy S. Aroma-volatile profile of black morel () grown in Israel[J]. Journal the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2018, 8(1): 346-353.

[7] Shameem N, Kamili AN, Ahmad M, et al. Antimicrobial activity of crude fractions and morel compounds from wild edible mushrooms of North western Himalaya[J]. Microbial Pathogenesis, 2017, 105: 356-360.

[8] Su CA, Xu XY, Liu DY, et al. Isolation and characterization of exopolysaccharide with immunomodulatory activity from fermentation broth of[J]. Daru J Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2013, 21(1): 1-6.

[9] Ower RD. Notes on the development of the morel ascocarp:[J]. Mycologia, 1982, 74(1): 142-144.

[10] 赵永昌, 柴红梅, 李树红, 等. 云南羊肚菌居群多样性研究[J]. 西南农业学报, 2008, 21(2): 444-447.

[11] Yoon CS, Gessner RV, Romano MA. Population genetics and systematics of the Morchella esculenta complex[J]. Mycologia, 1990, 82(2): 227-235.

[12] Wipf D, Bedell JP, Munch JC, et al. Polymorphism in morels: isozyme electrophoretic analysis[J]. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 1996, 42: 819-827.

[13] Royse DJ, May B. Interspecific allozyme variation amongspp. and its inferences for systematics within the Genus [J]. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, 1990, 18(7/8): 475-479.

[14] Wipf D, Munch J C, Botton B, et al. DNA Polymorphism in Morels: Complete Sequences of the Internal Transcribed Spacer of Genes Coding for rRNA in(Yellow Morel) and(Black Morel)[J]. Applied and Environmental Micriobiology, 1996, 62(9): 3541-3543.

[15] Buscot F, Wipf D, Battista CD, et al. DNA polymorphism in morels: PCR/RFLP analysis of theribosomal DNA spacers and microsatellite-primed PCR[J]. Mycological Research, 1996, 100(1): 63-71.

[16] Du XH, Zhao Q, Yang ZL, et al. How well do ITS rDNA sequences differentiate species of true morels ()?[J]. Mycologia, 2012, 104(6): 1351-1368.

[17] Barseghyan GS, Kosakyan A, Isikhuemhen OS, et al. Phylogenetic analysis within genera(Ascomycota, Pezizales) and Macrolepiota (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) inferred from rDNA ITS and EF- α sequences, in Systematic and Evolution of Fungi. Misra J.K., Tewari J.P. & S.K. Deshmukh (Eds.), Science Publishers, Enfield, NH, USA, 2012: 159-205.

[18] Wipf D, Fribourg A, Munch JC, et al. Diversity of the internal transcribed spacer of rDNA in morels[J]. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 1999, 45: 769-778.

[19] Gessner RV. Genetics and systematics of North American populations of[J]. Canandian Journal of Botany, 1995, 73(Suppl. 1): S967-S972.

[20] Dalgleish HJ, Jacobson KM. A first assessment of genetic variation among Morchella esculenta (morel)populations[J]. Journal of Heredity, 2005, 96(4): 396-403.

[21] Degreef J, Fischer E, Sharp C, et al. African(Ascomycota, Pezizales) revealed by analysis of nrDNA ITS[J]. Nova Hedwigia, 2009, 88: 11-22.

[22] Taşkin H, Büyükalaca S, Doğan HH, et al. A multigene molecular phylogenetic assessment of true morels ()in Turkey[J]. Fungal Genetics and Biology, 2010, 47: 672-682.

[23] Du XH, Zhao Q, Yang ZL. A review on research advances, issues, and perspectives of morels[J]. Mycology, 2015, 6(2): 78-85.

[24] Loizides M, Bellanger JM, Clowez P, et al. Combined phylogenetic and morphological studies of true morels (Pezizales, Ascomycota) in Cyprus reveal significant diversity, includingandspp. nov. [J]. Mycological Progress, 2016, 15(4): 39.

[25] Richard F, Bellanger JM, Clowez P, et al. True morels (, Pezizales) of Europe and North America: evolutionary relationships inferred from multilocus data and a unified taxonomy[J]. Mycologia, 2015, 107(2): 359-382.

[26] Pildain MB, Visnovsky SB, Barroetaveña C. Phylogenetic diversity of true morels (), the main edible non-timber product from native Patagonian forests of Argentina[J]. Fungal Biology, 2014, 118(9-10): 755-763.

[27] O’Donnell K, Rooney AP, Mills GL, et al. Phylogeny and historical biogeography of true morels () reveals an early Cretaceous origin and high continental endemism and provincialism in the Holarctic[J]. Fungal Genetics and Biology, 2011, 48(3): 252-265.

[28] Taşkın H, Büyükalaca S, Hansen K, et al. Multilocus phylogenetic analysis of true morels () reveals high levels of endemics in Turkey relative to other regions of Europe[J]. Mycologia, 2012, 104(2): 446-461.

[29] Du XH, Zhao Q, O’Donnell K, et al. Multigene molecular phylogenetics reveals true morels () especially species-rich in China[J]. Fungal Genetics and Biology, 2012, 49: 455-469.

[30] Yatuiik I, Saar I, Kalamees K, et al. Epitypification ofsteppicola (Morchellaceae, Pezizales), a morphologically, phylogenetically and biogeographically distinct member of the Esculenta Clade from central Eurasia[J]. Phytotaxa, 2016, 284(1):31-40.

[31] Voitk A, Beug MW, O'Donnell K, et al. Two new species of true morels from Newfoundland and Labrador: cosmopolitanand parochial[J]. Mycologia, 2016, 108(1): 31-37.

[32] Taşkın H, Doğan H, Büyükalaca S, et al., an autumn species from Turkey[J]. Mycotaxon, 2015, 130(1): 215-221.

[33] Taşkın H, Doğan H, Büyükalaca S, et al. Four new morel () species in thesubclade () from Turkey[J]. Mycotaxon, 2016, 131(2): 467-482.

[34] Clowez P, Alvarado P, Becerra M, et al.sp. nov. (Ascomycota, Pezizales): A new but widespread morel in Spain[J]. Boletín de la Sociedad Micológica de Madrid, 2014, 38 (2): 251-260.

[35] Elliott TF, Bougher NL, O’Donnell K, et al. Morchella australiana sp. nov., an apparent Australian endemic from New South Wales and Victoria[J]. Mycologia, 2014, 106(1): 113-118.

[36] Pinzón-Osorio CA, Jonás Pinzón-Osorio J. First report of family Morchellaceae (Ascomycota: Pezizales) for Colombia[J]. Revista peruana de biología, 2017, 24(1): 105-110.

[37] Loizides M, Alvarado P, Clowez P, et al, andor:a study of three poorly known Mediterranean morels,with nomenclatural updates in section Distantes[J]. Mycol Progress, 2015, 14(3): 1-18.

[38] Acar İ, Uzun Y. An Interesting Half-Free Morel Record for Turkish Mycobiota (M. Kuo, M.C. Carter & J.D.Moore)[J]. Ekim, 2017, 8(2): 125-128.

[39] Baran J, Boroń P. Two species of true morels (the genus, Ascomycota) recorded in the Ojców National Park (south Poland)[J]. Acta Mycologica, 2017, 52(1): 1094.

[40] 宋晓英, 石宗水, 朱文华, 等. 羊肚菌在泰山山系周围分布及生态习性的调查研究[J]. 山东林业科技, 2006, 4: 51-52.

[41] Emery MR, Barron ES. Using Local Ecological Knowledge to Assess Morel Decline in the U.S. Mid–Atlantic Region[J]. Economic Botany, 2010, 64(3): 205-216.

[42] 赵永昌, 吴毅歆, 严世武. 羊肚菌发生区气候土壤生态环境研究[J]. 中国食用菌, 1998, 17(3): 4-6.

[43] Matočec N, Kušan I, Mrvoš D, et al. The autumnal occurrence of the vernal genus(Ascomycota, Fungi)[J]. Natura Croatica, 2014, 23(1): 163-178.

[44] Tiffany LH, Knaphus G, Huffman DM. Distribution and Ecology of the Morels and False Morels of Iowa[J]. Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science, 1998, 105(1): 1-15.

[45] 王尚荣, 刘高峰, 赵贵红. 菏泽黄河冲积平原羊肚菌资源及生态环境调查[J]. 中国食用菌, 2008, 27(6): 12-14.

[46] Manikandan K, Sharma VP, Kumar S, et al. Edaphic conditions of natural sites of Morchella and Phellorinia[J]. Mushroom Research, 2011, 20(2): 117-120.

[47] Winder RS, Keefer ME. Ecology of the 2004 morel harvest in the Rocky Mountain Forest District of British Columbia[J]. Botany, 2008, 86: 1152-1167.

[48] Boddy L, Büntgen U, Egli S, et al. Climate variation effects on fungal fruiting[J]. Fungal Ecology, 2014, 10: 20-33.

[49] Liu HM, Xu JJ, Li X, et al. Effects of microelemental fertilizers on yields, mineral element levels and nutritional compositions of the artificially cultivated[J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2015, 189: 86-93.

[50] Liu Q, Liu H, Chen C, et al. Effects of element complexes containing Fe, Zn and Mn on artificial morel's biological characteristics and soil bacterial community structures[J]. PLoS ONE, 2017, 12(3): e0174618.

[51] Mohammad J, Khan S, Shah MT, et al. Essential and nonessential metal concentradions in morel mushroom() in Dir-Kohistan,Pakistan[J]. Pakistan Journal of Botany, 2015, 47(SI): 133-138.

[52] 陈诚, 李强, 黄文丽, 等. 羊肚菌白霉病的发生对土壤真菌群落结构的影响[J]. 微生物学报, 2017, 44(11): 2652-2659.

[53] 沈洪, 汪虹, 赵永昌, 等. 采用变性梯度凝胶电泳研究羊肚菌土壤真菌群落结构[J]. 食用菌学报, 2009, 16(2): 6-9.

[54] 沈洪. 云南羊肚菌分类及其生长土壤微生物群落结构分析[D]. 南京: 南京农业大学, 2007.

[55] 姚丽. 云南羊肚菌生长土壤真菌群落结构分析[D]. 南京: 南京农业大学, 2009.

[56] Singh SK, Kamal S, Tiwari M, et al. Myco-ecological studies of natural morel sites in Shivalik hills of Himachal Pradesh[J]. India Micologia Aplicada International, 2004, 16(1): 1-6.

[57] Pion M, Spangenberg JE, Simon A, et al. Bacterial farming by the fungus[J]. Proceeding of the Royal Society B, 2013, 280: 20132242.

[58] Larson AJ,Cansler CA, Cowdery SG, et al. Post-fire morel (Morchella) mushroom abundance, spatial structure, and harvest sustainability[J]. Forest Ecology and Management, 2016, 377: 16-25.

[59] Reazin C, Morris S, Smith JE, et al. Fires of differing intensities rapidly select distinct soil fungal communities in a Northwest US ponderosa pine forest ecosystem[J]. Forest Ecology and Management, 2016, 377: 118-127.

[60] Pilza D, Webera NS, Carterb MC, et al. Productivity and diversity of morel mushrooms in healthy, burned, and insect-damaged forests of northeastern Oregon[J]. Forest Ecology and Management, 2004, 198: 367-386.

[61] Masaphy S, Zabari L. Observations on post-fire black morel ascocarp development in an Israeli burnt forest site and their preferred micro-sites[J]. Fungal Ecology, 2013, 6: 316-318.

[62] McFarlane EM, Pilz D, Weber NS. High-elevation gray morels and otherspecies harvested as non-timber forest products in Idaho and Montana[J]. Mycologist, 2005, 19 (2): 62-68.

[63] Li Q, Xiong C, Huang WL, et al. Controlled surface fire for improving yields of[J]. Mycol Progress, 2017, 16(11-12): 1057-1063.

[64] Mihil JD, Bruhn JN, Bonello P. Spatial and temporal patterns of morel fruiting[J]. Mycological Research, 2007, 113(3): 339-346.

[65] Masaphy S, Zabari L, Goldberg D. New long-season ecotype offrom northern Israel[J]. Micologia Aplicada International, 2009, 21(2): 45-55.

[66] Golway M, Amir R, Goldberg D, et al.exhibiting a long fruiting season[J]. Mycological Research, 2000, 104 (8): 1000-1004.

[67] Buscot F. Field observations on growth and development ofand Mitrophora similibera in relation to forest soil temperature[J]. Canadian Journal of Botany, 1989, 67: 589-593.

[68] Ower RD, Mills GL, Malachowski JA. Cultivation of, 1985, US4757640 (A).

[69] Masaphy S. External ultrastructure of fruit body initiation in[J]. Mycological Research, 2005, 109 (4): 508-512.

[70] Masaphy S. Biotechnology of morel mushrooms: successful fruiting body formation and development in a soilless system[J]. Biotechnol Letters, 2010, 32: 1523-1527.

[71] 赵永昌, 王芳, 吴毅歆. 羊肚菌菌核的形成研究[J]. 中国食用菌, 1998, 17(1): 5-7.

[72] Buscot F, Roux J. Association between living roots and ascocarps of Morchella rotunda[J]. Transactions of the British Mycological Society, 1987, 89 (2): 249-252.

[73] Buscot F. Mycorrhizal succession and morel biology. In Read DJ, Lewis DH, Fitter AH, Alexander IJ. (eds.). Mycorrhizas in Ecosystems. Wallingford, United Kingdom: CAB International, 1992: 220-224.

[74] Dahlstrom JL, Smith JE, Weber NS. Mycorrhiza-like interaction bywith species of the Pinaceae in pure culture synthesis[J]. Mycorrhiza, 2000, 9 (5): 279-285.

[75] Tedersoo L, May TW, Smith ME. Ectomycorrhizal lifestyle in fungi: global diversity, distribution, and evolution of phylogenetic lineages[J]. Mycorrhiza, 2010, 20 (4): 217-263.

[76] Stefani FO, Sokolski S, Wurtz TL, et al.: a unique belowground structure and a new clade of morels[J].Mycologia, 2010, 102(5): 1082-1088.

[77] Dayi B, Kyzy AD, Abduloglu Y, et al. Investigation of the ability of immobilized cells to different carriers in removal of selected dye and characterization of environmentally friendly laccase of[J]Dyes and Pigments, 2018, 151: 15-21.

[78] Papinutti L, Lechner B. Influence of the carbon source on the growth and lignocellulolytic enzyme production bystrains[J]. Journal of Industral Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2008, 35: 1715-1721.

[79] Thakur N,Tripathi A, Sagar S, et al. Estimation of extracellular ligniolytic enzymes from wildsp. andsp[J]. Internaional Journal of Advanced Research, 2017, 5(10): 968-974.

[80] 陈国梁, 张向前, 贺晓龙, 等. 五种羊肚菌液体培养过程胞外酶活性变化研究[J]. 北方园艺, 2010(10): 210- 213.

[81] Kamal S, Singh S K, Tiwari M. Role of enzymes in initiating sexual cycle in different species of[J]. Indian Phytopathology, 2004, 57: 18-23.

[82] Thankur M. Qualitative and quantitative screening of vegetative mycelium ofspecies for the activity of extracellular enzymes in North West Himalayas[J]. International Journal of Current Research in Biosciences and Plant Biology, 2016, 3(6): 123-128.

[83] Tiwari M, Singh S K, Kamal S, et al. Extracellular enzyme polymorphism inand related species[J]. Journal of Mycology and Plant Pathology, 2004, 36: 64-68.

[84] Chen LJ, Wang F, Zhao YC, et al. Extracellular enzyme activity of sclerotia-forming and non-sclerotia-formingstrains[J]. Agricultural Science & Technology, 2013, 14(10): 1392-1396, 1408.

[85] Czövek P, Király I. Inducible trehalase enzyme activity ofPersoon mycelium[J]. Acta Microbiologica et Immunologica Hungarica, 2011, 58(1 ): 1-11.

[86] Tan H, Tang J, Li XL, et al. Biochemical characterization of a psychrophilic phytase from an artificially cultivable morel[J]. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2017, 27(12): 2180-2189.

[87] Cavazzoni V, Manzoni M. Extracellular cellulytic complex from: Production and purification[J]. Lebensmttel-Wissenschaft Technologie, 1994, 27: 73-77.

[88] Baute MA, Deffieus G, Baute R. Bioconversion of carbohydrates to unusua pyrone compounds in fungi: occurrence in micorthecin in morels[J]. Phytochemtry, 1986, 25(6): 1472-1473.

[89] Hobbie EA, Weber NS, Trappe JM. Mycorrhizal vs saprotrophic status of fungi: the isotopic evidence[J]. New Phytologist, 2001, 150: 601-610.

[90] Hobbie EA, Rice SF, Smith WN, et al. Isotopic evidence indicates saprotrophy in post-firein Oregon and Alaska[J]. Mycologia, 2016, 108(4): 638-645.

[91] Žižka Z, Gabriel J. Autofluorescence of the fungusvar.[J]. Folia Microbiology, 2011, 56: 166-169.

[92] Kellner H, Luis P, Buscot F. Diversityof laccase-like multicopperoxidase genes in Morchellaceae: identification of genes potentially involved in extracellularactivities related to plant litter decay[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2007, 61: 153-163.

[93] Fujimura K E, Smith JE, Horton TR, et al. Pezizalean mycorrhizas and sporocarps in ponderosa pine (Pinusponderosa) after prescribed fires in eastern Oregon, USA[J]. Mycorrhiza, 2005, 15(2): 79-86.

[94] Buscot F, Roux J. Association between living roots and ascocarps of[J]. Transactions of the British Mycological Society, 1987, 89 (2): 249-252.

[95] Buscot F, Kottke I. The association of(Pers.) Boudier with roots of Picea abies(L.) Karst[J]. New Phytologist, 1990, 116: 425-430.

[96] Buscot F. Ectomycorrhizal types and endobacteria associated with ectomycorrhizas of(Fr.) Boudier with Picea abies (L.) Karst[J]. Mycorrhiza, 1994, 4: 223-232.

[97] Stefani FO, Sokolski S, Wurtz TL, et al.: a unique belowground structure and a new clade of morels[J]. Mycologia, 2010, 102(5): 1082-1088.

[98] Buscot F. Synthesis of two types of association betweenand Picea abies under controlled culture conditions[J]. Journal of Plant Physiology, 1992, 141: 12-17.

[99] Dahlstrom JL, Smith JE, Weber NS. Mycorrhiza-like interaction bywith species of the Pinaceae in pure culture synthesis[J]. Mycorrhiza, 2000, 9: 279-285.

[100] Yu D, Bu FF, Hou JJ, et al. A morel improved growth and suppressedinfection in sweet corn[J]. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2016, 32(12): 192.

[101] Bala P, Gupta D, Sharma YP. Mycotoxin research and mycoflora in some dried ediblemorels marketed in Jammue and Kashimir, India[J]. Journal of Plant Development Sciences, 2017, 9 (8): 771-778.

[102] 何培新, 刘伟, 贺新生, 等. 粗柄羊肚菌内生真菌多样性研究[J]. 郑州轻工业学院学报(自然科学版), 2014, 29(3): 1-6.

[103] Li CN, Li LH, Liao HJ, et al. Facilitation ofon[J]. Journal of Pure and Applied Microbiology, 2013, 7(4): 2495-2502.

[104] Beug MW. An overview of mushroom poisonings in North America[J]. Mycophile, 2004, 45(2) : 4.

[105] Pfab R,Haberl B,Kleber J,et al. Cerebellar effects after consumption of edible morels (,)[J]. Clinical Toxicology, 2008, 46: 259.

[106] Saviuc P, Harry P, Pulce C, et al. Can morels (sp.) induce a toxic neurological syndrome?[J]. Clinical Toxicology, 2010, 48: 365.

[107] Zhang N, O’Donnell K, Sutton D A, et al. Members of thespecies complex that cause infections in both humans and plants are common in the environment[J]. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 2006, 44: 2186-2190.

[108] Teixeira ABA, Trabasso P, Moretti-Branchini ML, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis caused byin an allogeneic bone marrow transplant recipient[J]. Mycopathologia, 2003, 156: 309-312.

[109] Ostry V. Alternaria mycotoxins: an overview of chemical characterization, producers, toxicity, analysis and occurrence in foodstuffs[J]. World Mycotoxin Journal, 2008, 1(2): 175-178.

[110] Bisht V,Singh BP,Arora N,et al.Antigenic and allergenic cross-reactivity ofwith other fungi[J]. Annals of Allergy Asthma and Immunology, 2002, 89(3): 285-291.

[111] Sushant Sud, Vd Khyati. A review of toxic effects and aphrodisiac action of(wild morel-Guchhi mushroom)-A Himalaya delight[J]. European Journal of Pharmaceutical and medical Research, 2017,4(8): 726-730.

[112] Rohe M, Meinhardt E. Both open reading frames of the linear plasmid pMC3-2 from the ascomyceteare transcribed in vivo[J]. Current Genettic, 1992, 22: 507-509.

[113] Meinhardt F, Karl Esser K. Linear extrachromosomal DNA in the morel Morchella conica[J]. Current Genetics, 1984, 8(1): 15-18.

[114] Volk TJ, Leonard TJ. Cytology of the life-cycle of[J]. Mycological Research, 1990, 94(3): 399-406.

[115] Alvarado-Gastillo, et al. Understanding the life cycle of morels (spp.)[J]. Revista Mexicana de Micologica, 2014, 40: 47-50.

[116] 陈立佼. 羊肚菌属真菌子囊发育及交配相关基因研究[D]. 昆明: 云南大学, 2015.

[117] Chai HM, Chen LJ, Chen WM, et al. Characterization of mating-type idiomorphs suggests that Morchella importuna, Mel-20 and M. sextelata are heterothallic[J]. Mycol Progress, 2017(16): 743-752.

[118] 贺新生, 张能, 赵苗. 栽培羊肚菌的形态发育分析[J]. 食药用菌, 2016, 24(4): 222-229, 238.

[119] Schmidt EL. Spore germination of and carbohydrate colonization byat different soil temperatures[J]. Mycologia, 75(5): 870-875.

[120] 李洁, 张云霞, 邱德江. 不同因素对羊肚菌孢子萌发和菌丝生长的影响[J]. 河北林业科技, 2004(2): 1-2.

[121] 刘伟, 蔡英丽, 何培新, 等. 粗腿羊肚菌子囊孢子萌发过程及其细胞核行为[J]. 食用菌学报, 2017, 24(1): 18-20.

[122] Singh SK,Tiwari M, Kamal S,Yadav SC, Singh S.Cytology and hyphal interactions to determine mating types in Morchella esculenta[J]. Mushroom Research, 2006, 15(1): 11-17.

[123] Volk TJ, Leonard TJ. Experimental studies on the morel. I. hetrokaryon formation between monoascosporous strains of[J]. Mycologia, 1989, 81(1): 523-531.

[124] Kalyoncu F, Oskay M, KalyoncuM. The effects of some environmental parameters on mycelial growth of sixspecies[J]. Journal of Pure and applied Micriobiology, 2009, 3(2): 467-472.

[125] Kalm E,Kalyoncu F. Mycelial growth rate of some morels (spp.) in four different microbiological media[J]. American-Eurasian Journal of Agricultral and Environmental Sciences, 2008, 3(6): 861-864.

[126] Buscot F. Mycelial differentiation ofin pure culture[J]. Mycological Research, 1993, 97 (2): 136-140.

[127] Kalmış E, Kalyoncu E. The effects of some environmental parameters on mycelial growth of two ectomycorrhizal fungi,and[J]. Mycologia Balcania, 2008, 5: 115-118.

[128] Güler P, Atkan O. Cultural characteristics ofmycelium on some nutrients[J]. Turkish Journal of Biology, 2000, 24: 783-794.

[129] Hervey A, Bistis G, Leong I. Cultural studies of single ascospore isolates of Morchella esculenta[J]. Mycologia, 1978, 70(6): 1269-1274.

[130] 陈立佼, 柴红梅, 黄兴奇, 等. 尖顶羊肚菌单孢菌株群体培养特性研究[J]. 生物技术, 2011, 21(6): 63-70.

[131] Alvarado-Castillo Mata G, Pérez-Vázquez A, Martínez-Carrera D, et al. Formación de esclerocios eny, in vitro[J]. Revista mexicana de micología, 2012, 35: 35-41.

[132] Prasher IB, Sharma M, Chandel VC, et al. Effect of physical factors, carbon and nitrogen sources on the growth and sclerotial production in(Sow.) Pers[J]. The Journal of Biological and Chemical Chronicles, 2017, 3(1): 20-27.

[133] Güler P, Ozkaya EG. Morphological development ofmycelium on different agar media[J]. Journal of Environmental Biology, 2009, 30(4): 601-604.

[134] Güler P, Ozkaya EG. Sclerotial structures of Morchella conica in agar media with different carbohydrate[J]. Acta Alimentaria, 2008, 37 (3): 347-357.

[135] Volk TJ, Lenonard TJ. Physiological and environmental studies of sclerotium formation and maturation in isolates of Morchella crassipes[J]. Applied and Environmental Micriobiology, 1989, 55(12): 3095-3100.

[136] Kanwal HK, Reddy MS. The effect of carbon and nitrogen sources on the formation of sclerotia inspp[J]. Annals of Microbiology, 2012, 62: 165-168.

[137] Güler P, Bozcuk S, Mutlu F, et al. Propolis effection sclerodial formations of Morchella conica Pers[J]. Pakistan Journal of Botany,2005, 37(4): 1015-1022.

[138] Alvarado-Castillo G, Vázquez AP, Martínez-Carrera D, et al.sclerotia production through grain supplementation[J]. Interciencia, 2011, 36(10): 768-773.

[139] Király I, Czövek P. Oxidative burst induced pseudosclerotium formation ofZerova on different malt agar media[J]. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 2007, 53(8): 975-982.

[140] Kanwal HK, Reddy MS. Influence of sclerotia formation on ligninolytic enzyme production in[J]. Journal of Basic Microbiology, 2014, 54 (Suppl1): 63-69.

[141] Amir R, Levanon D, HadarY, et al. Morphology and physiology ofduring sclerotial formation[J]. Mycological Research, 1993, 97 (6): 683-689.

[142] Chen LJ, Chai HM, Chen WM, et al. Expressing difference in sclerotial formation of[J]. Indian Journal of Microbiology, 2014, 54(3): 274-283.

[143] Miller SL, Torres P, McClean TM. Persistence of basidiospores and sclerotia of ectomycorrhizal fungi andin soil[J]. Mycologia, 1994, 86(1): 89-95.

[144] 贺新生, 张能, 赵苗, 等. 栽培羊肚菌的形态发育分析[J]. 食药用菌, 2016, 24(4): 222-229, 238.

[145] 刘伟, 蔡英丽, 何培新, 等. 棱羊肚菌无性孢子形态及显微结构观察[J]. 菌物研究, 2016, 14(3): 157-161.

[146] 谭昊, 甘炳成, 彭卫红, 等. 羊肚菌单孢菌株采用“人工授粉”进行栽培[P]. 中国: CN 106416751A,2017-03-22.

(完)