Sub-dissociative dose ketamine administration for managing pain in the emergency department

Sergey Motov, Jefferson Drapkin, Antonios Likourezos, Joshua Doros, Ralph Monfort, John Marshall

Department of Emergency Medicine, Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA

KEY WORDS: Ketamine; Analgesia; Emergency department; Sub-dissociative; Infusion

INTRODUCTION

Background

Ketamine is a non-competitive NMDA/glutamate receptor complex antagonist that diminishes pain by reducing central sensitization, “wind-up” phenomenon,and hyperalgesia at the level of the spinal cord (dorsal ganglion) and central nervous system.[1]Ketamine administration in a sub-dissociative dosing range(0.1–0.3 mg/kg) results in anti-hyperalgesia, antiallodynia, and anti-tolerance which makes ketamine a useful analgesic for managing a variety of acute and chronic painful conditions without adversely affecting hemodynamics and cognition.[1–3]Sub-dissociative dose ketamine (SDK) provides effective analgesia to patients with acute traumatic and non-traumatic pain, chronic and cancer pain, opioid-tolerant pain, and opioid-induced hyperalgesic states in the emergency department (ED).[4–13]

Importance

A large body of evidence supports the use of SDK analgesia administered either as an adjunct to opioids or as a single agent in the ED and in the pre-hospital setting which results in significant pain relief and opioid sparing.[4–13]Several strategies of SDK administration in the ED exist that include: intravenous push (IVP) dose (over 2–5 minutes), which is associated with relatively high rates of minor but bothersome psychoperceptual side effects(feeling of unreality and dizziness),[5–13]short infusion(SI) given over 15 minutes, which is associated with signifi cantly fewer bothersome side effects and preserved analgesic efficacy,[14,15]and continuous infusion (CI) for selected groups of patients.[6,16–19]

Goals of this investigation

The goal of this investigation is to describe our experience with SDK analgesia in the ED with respect to type of SDK administration (IVP, SI or CI), dosing range, co-analgesic administration, and rates of side effects. We hypothesized that this analgesic modality can be utilized in the ED across wide range of acute and chronic painful conditions and that its administration may lead to reduced co-analgesic (opioids, non-opioids)administration and minimal risk for serious adverse effects.

METHODS

Study design and setting

We retrospectively reviewed medical charts of patients who were admitted to our ED and received SDK analgesia over a six-year period (2010–2016). The study was conducted at a 711-bed urban community teaching hospital with an annual ED census of greater than 120,000 visits. In our ED, the predominant route of SDK administered is a short infusion with a weight-based dose of 0.3 mg/kg given over 15 minutes. Additionally,we use continuous SDK infusion with a starting dose of 0.15 mg/(kg•h) that is titrated up as necessary by the treating physician every 20–30 minutes by 2.5–5 mg and intravenous weight-based push dose of SDK of 0.3 mg/kg given over 3–5 minutes. Weight-based intravenous SDK order sets are built into our electronic medical record system (Allscripts™), prepared by ED pharmacists, and administered by ED nursing staff via infusion pump. All patients requiring continuous SDK infusion are placed on a cardiac monitor with continuous pulse oximetry. This study was approved by the hospital’s institutional review board.

Selection of participants

Patients 18 years and older presenting with a variety of acute and chronic painful conditions for which they received SDK analgesia in the ED were eligible for the study. Patients were excluded if they had received intravenous ketamine for a purpose other than analgesia,such as for procedural sedation, anxiolysis, or end-of-life care; or if patients were enrolled in SDK-related research projects.

Methods and measurements

Data collection was performed by querying the ED electronic medical record (Allscripts™) database.Data extracted included: age, sex, chief complaint, fi nal diagnoses, pre- and post-SDK dosing, time range for continuous infusion, analgesics administered before and after SDK administration, and adverse effects.

Outcomes

The primary o utcomes were: (1) dosing for intravenous push, short infusion and continuous infusion and duration of the continuous ketamine infusion within each group and with respect to final diagnoses; (2) percentage of patients receiving analgesic medications before and after SDK administration; and (3)overall rates of adverse effects for intravenous push dose,short- and continuous infusions.

Data analysis

The data analyses consisted primarily of descriptive statistics: baseline characteristics of patients in each treatment group were described in terms of mean±standard deviation for continuous variables and frequency (percent) for categorical variables. Student’s t-test was used to compare simple group differences in terms of means (e.g., age), while the chi-square test was used to look at differences in terms of percent rates (e.g.,sex). All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS v.24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

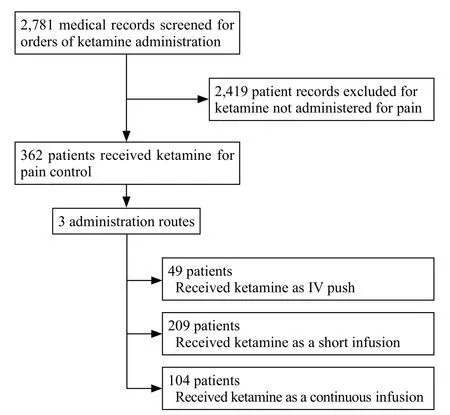

We reviewed 2,781 medical records containing orders for ketamine which occurred between January 2010 and December 2016 (Figure 1). Of those, 2,419 patient records were excluded due to ketamine use other than for analgesia. The remaining 362 subjects who received SDK for pain control were enrolled in the study, with 49 patients in the intravenous push (IVP)group, 209 in the short infusion (SI) group, and 104 in the continuous infusion (CI) group. The mean age was 48.8 years old, with 39.2% male patients. The majority of patients who received SDK analgesia presented with chief complaints related to abdominal pain (31.2%) and musculoskeletal pain (22.1%) which roughly correlated with fi nal diagnoses.

Figure 1. Study fl ow diagram for patient selection.

Main outcomes

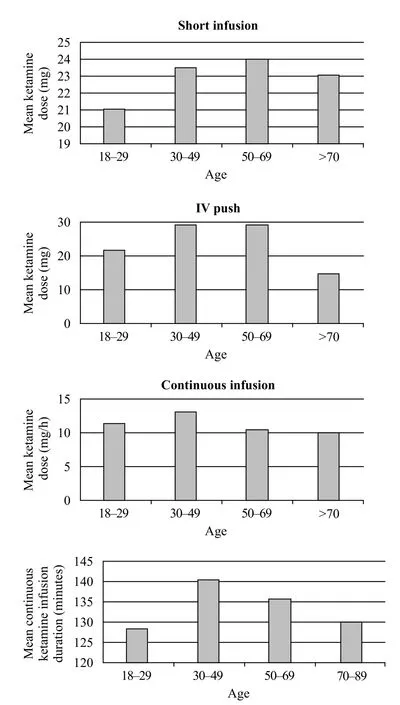

Figure 2. Mean ketamine infusion dose and duration for different age groups.

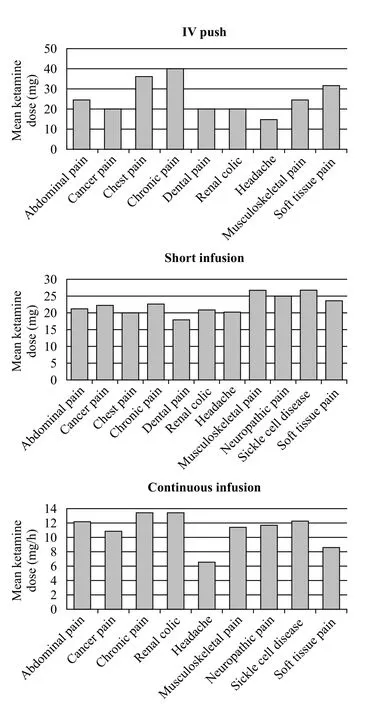

The mean SDK dose for IVP was 26.3 mg (10–50 mg), for SI was 23.4 mg (6–50 mg), and for CI was 11.3 mg/hour (6.0–22.50 mg/hour) with a mean CI duration of 135.87 minutes (20–480 minutes). Patients in the 30–49 years age group received the highest mean dose (29.3 mg) of SDK given via IVP, 50–69 years age group received the highest mean dose (24 mg) for SI,and 30–49 years age group (12.2 mg/hour) for CI. The 30–49 years age group also received the longest mean CI duration of 140.6 minutes (Figure 2). Upon comparing the dosing range of SDK across fi nal diagnoses, patients with chronic pain and non-traumatic chest pain received the largest mean doses (40 mg and 36 mg) via IVP route,patients with musculoskeletal pain and vaso-occlusive painful crisis received the largest mean doses (26.6 mg and 26.7 mg) via SI route, and patients with chronic pain and renal colic pain received the largest mean doses (13.4 mg and 13.5 mg) via CI route (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Mean ketamine infusion dose and duration for final diagnosis groups.

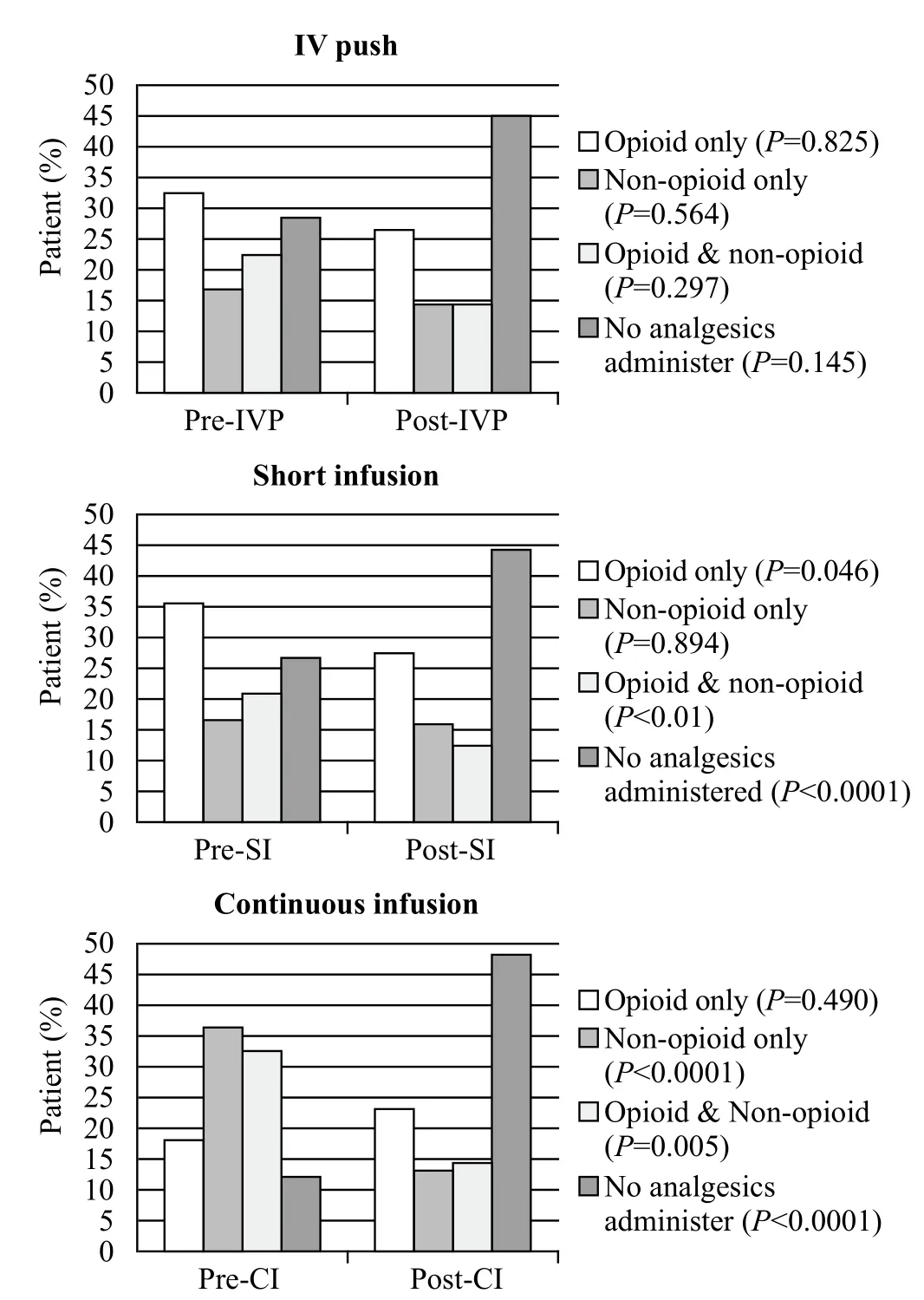

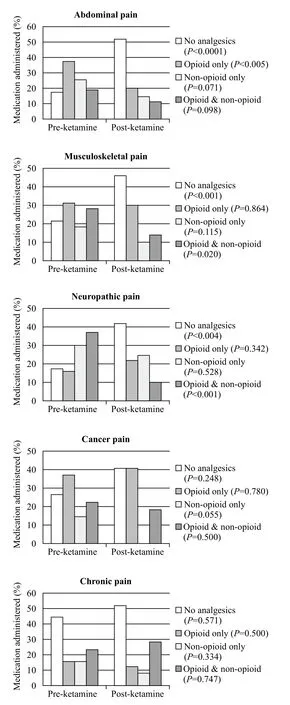

Figure 4 shows the percentages of patients who received analgesia before and/or after SDK administration. We observed a decrease in post-SDK opioid administration in the IVP group from 33% to 26% (P=0.825) and from 36% to 27% (P=0.046) in the SI group. In addition,we noticed a significant increase in the percentage of patients not requiring post-SDK analgesia administration in all three groups: from 28% to 45% (P=0.145) in the IVP group, from 27% to 44% (P<0.0001) in the SI group, and from 12% to 49% (P<0.0001) in the CI group. The CI group showed a slight overall increase in opioid requirements after SDK administration (from 18%to 23%, P=0.490). Twenty-four patients (6.6%) received SDK without any other analgesics, and 62 patients(59.6%) out of 104 received the SDK bolus dose of 0.3 mg/kg prior to the continuous infusion.

Administration of analgesics before and after SDK varied greatly amongst the five most prevalent clinical diagnoses groups. Patients with abdominal,musculoskeletal, and neuropathic pain were found to have significant differences in not receiving any analgesic pre-and post-SDK administration: 17.7% to 52.2% (P<0.0001), 21.3% to 46.3% (P<0.001), and 17.5% to 42.1% (P<0.004), respectively. Furthermore,patients with abdominal pain had signifi cant decrease in post-SDK opioid analgesic administration from 37.2% to 20.4% (P<0.005) (Figure 5).

Figure 4. The percentages of patients who received analgesia before and/or after SDK administration.

Figure 5. Total analgesics administered pre- & post-ketamine for most common fi nal diagnoses.

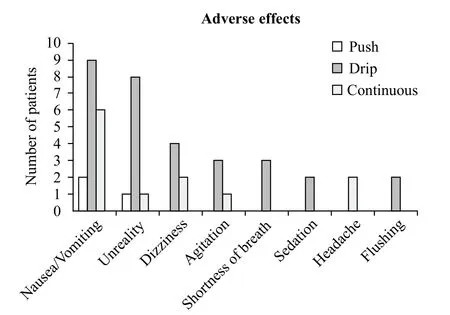

Three hundred and sixteen (87.3%) patients had no documentation of adverse effects. For remaining 46 patients (12.7%), 8 adverse effects were reported (Figure 6).

Three hundred forty-four patients (95%) had documented pre-SDK administration NRS pain scores and 215 (59%) post-administration. However, we were unable to make any assertion with respect to analgesic efficacy of SDK due to the facts that retrospective pain scores are unreliable and insufficiently precise in evaluating pain relief solely attributed to ketamine.

DISCUSSION

SDK administration in the form of intravenous push or short infusion is becoming increasingly popular as a viable adjunct to or substitute for opioid analgesics for managing a variety of acute and chronic painful conditions in the pre-hospital arena and in the ED.Retrospective case series, prospective observational, and randomized controlled trials have demonstrated good(even comparable to morphine) analgesic efficacy and modest rates of minor but bothersome side effects of SDK given as an intravenous push dose for ED patients with acute pain.[4–13]

The most recent data support the use of a short infusion of SDK (over 15 minutes) as a preferred route due to the fact that it resulted in a significant decrease of such side effects (by 40%) with preserved analgesic effi cacy.[14,15]Of note, there is a paucity of data supporting the use of continuous SDK infusion (longer than 1 hour) in the ED6 despite a growing body of literature that advocates for utilization of continuous intravenous ketamine infusion either as an adjunct to opioids or as a single agent for pediatric and adult patients with predominantly chronic painful conditions.[16–19]

Figure 6. Reported adverse effects.

Our retrospective chart review demonstrates feasibility of SDK administration in the ED for a variety of acute and chronic painful conditions via intravenous push, short and continuous infusions across different age groups and across a variety of painful syndromes with a potential for opioid sparing and a reduced need for rescue analgesics administration.

Despite the low overall number of patients (13%)with documented adverse effects, we cannot truly make any recommendations regarding the safety of SDK in the ED, however, we did not fi nd any documented reports of major adverse effects that required interventions. Despite the trend towards higher rates of adverse effects in the short-infusion group, we believe that this route of SDK administration confers the best option in the ED based on the number of patients enrolled and overall change in pain scores.

The fact that SDK administration via IVP, SI and,especially, CI routes resulted in significant reduction of post-ketamine analgesic use by 16%, 18% and 37%respectively is very encouraging. Furthermore, the decrease in opioid requirements in the IVP and SI groups by 6% and 8.5% post-SDK administration demonstrates the opioid-sparing properties of SDK. In addition, our study showed signifi cant decreases in overall post-SDK analgesics administration for patients with abdominal,musculoskeletal, and neuropathic pain by 35%, 25%, and 25%, respectively, which could have reduced the length of stay and improved overall throughput of such patients in the ED.

Our data showed that SDK analgesia can be employed for geriatric patients with a broad range of painful syndromes in the ED, thus adding an additional analgesic modality with a potential for use when opioids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are contraindicated. Furthermore, our recently published study that specifically evaluated a role of continuous SDK infusions in the ED demonstrated an average decrease in pain score of 5.04; average dosing of infusion of 11.26 mg/hr with average duration time of 136 min, and nausea being the most prevalent adverse effect.[20]Thus we believe that continuous SDK infusion has a role in controlling pain in the ED with a potential to reduce the need for co-analgesics or rescue analgesic administration.

Despite the ever-growing body of evidence(including prospective randomized blinded studies) that support the use of SDK for managing pain in the ED and in pre-hospital setting, several barriers exist that preclude a widespread utilization of SDK in the ED’s across the country. An absence of practice standardization of dosing regimens, length of treatment, and management of side effects results in wide variation in practice. The designation of ketamine as a dissociative anesthetic irrespective of dosing regimen significantly limits its universal use as an analgesic with respect to perceived level of care, scope of providers’ practice and level of monitoring. Lack of formal FDA approval of SDK as a designated analgesic adversely affects the ability of health care practitioners to effectively administer this medication in the ED and on the hospital wards.[21]

In light of such limitations, our retrospective study,despite its limited data on safety and analgesic efficacy of SDK, provides further support for the role of ketamine in managing a variety of acute and chronic painful conditions across different age groups by describing in detail dosing regimens, routes and multitude of clinical indications. Furthermore, we believe that departmental and interdisciplinary protocols with clearly specified patient eligibility criteria as well as indications and contraindications to ketamine administration via IVP, SI,or CI should be in place before widespread use of this analgesic modality ought to be implemented in the ED.

Limitations

The retrospective design of the study, relatively small sample size, unreliable pain scores, and lack of documented adverse effects for 87% of patients were the major limitations of this study. In addition, data regarding prescribing information when extracted from medical records may not always be accurate. Lack of control group severely limited our ability to conclude that the results of this retrospective project were solely attributable to the SDK and not to other factors and analgesics operating and used during the same time period. Since the primary outcome of the study was the dosing regimens for IVP, SI and CI routes, dosages of individual analgesics administered before and after SDK were not abstracted.

As a result, we could not fully evaluate and compare the analgesic efficacy of SDK given by IVP, SI or CI routes as well as difference in pain score between different pain syndromes. Similarly, due to absence of documented adverse effects for all but 13% of patients,we could not make any conclusions regarding the safety of SDK that is given via IVP, SI or CI routes. Finally,the documented adverse effects among 46 patients were skewed towards the SI group due to the largest number of patients being in this group.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, SDK analgesia in the ED is a viable analgesic modality for managing a variety of acute and chronic painful conditions across a wide age spectrum of patients resulting in opioid sparing and decreased need for rescue analgesia. There is a need for more robust,prospective, randomized trials that will further evaluate the analgesic effi cacy and safety of short- and continuous ketamine infusion in the ED across a wide range of pain syndromes and different age groups.

Funding:This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval:This study was approved by the hospital’s institutional review board.

Conflicts of interest:All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Confl icts of Interest.The authors have no independent disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Contributors:Study concept and design: SM; Acquisition,analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors; Statistical analysis:AL; Drafting of the manuscript: SM, JD; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: SM; Study supervision: SM, JM.

REFERENCE

1 Gao M, Rejaei D, Liu H. Ketamine use in current clinical practice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016;37(7):865-72. Epub 2016 Mar 28.

2 Kurdi MS, Theerth KA, Deva RS. Ketamine: Current applications in anesthesia, pain, and critical care. Anesth Essays Res. 2014;8(3):283-9.

3 Tziavrangos E, Schug SA. Clinical Pharmacology: other adjuvants. In Macyntyre P, et al. Clinical Pain Management(Acute Pain), pp: 98-101. Second Edition, 2008 Hodder &Stoughton Limited.

4 Jennings PA, Cameron P, Bernard S. Ketamine as an analgesic in the pre-hospital setting: a systematic review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2011;55(6):638-43.

5 Ahern TL, Herring AA, Anderson ES, Madia VA, Fahimi J,Frazee BW. The fi rst 500: initial experience with widespread use of low-dose ketamine for acute pain management in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(2):197-201.

6 Ahern TL, Herring AA, Miller S, Frazee BW. Low-dose ketamine infusion for emergency department patients with severe pain. Pain Med. 2015;16(7):1402-9.

7 Lester L, Braude DA, Niles C, Crandall CS. Low-dose ketamine for analgesia in the ED: a retrospective case series. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(7):820-7.

8 Richards JR, Rockford RE. Low-dose ketamine analgesia:patient and physician experience in the ED. Am J Emerg Med.2013;31(2):390-4.

9 Beaudoin FL, Lin C, Guan W, Merchant RC. Low-dose ketamine improves pain relief in patients receiving intravenous opioids for acute pain in the emergency department: results of a randomized,double-blind, clinical trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(11):1193-202.

10 Bowers KJ, McAllister KB, Ray M, Heitz C. Ketamine as an adjunct to opioids for acute pain in the emergency department: a randomized controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(6):676-85.

11 Farnia MR, Babaei R, Shirani F, Momeni M, Hajimaghsoudi M, Vahidi E, et al. Analgesic effect of paracetamol combined with low-dose morphine versus morphine alone on patients with biliary colic: a double blind, randomized controlled trial. World J Emerg Med. 2016;7(1):25-9.

12 Motov S, Rockoff B, Cohen V, Pushkar I, Likourezos A,McKay C, et al. Intravenous subdissociative-dose ketamine versus morphine for analgesia in the emergency department: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66(3):222-9.

13 Majidinejad S, Esmailian M, Emadi M. Comparison of intravenous ketamine with morphine in pain relief of long bones fractures: a double blind randomized clinical trial. Emerg(Tehran). 2014;2(2):77-80.

14 Goltser A, Soleyman-Zomalan E, Kresch F, Motov S. Short(low-dose) ketamine infusion for managing acute pain in the ED:case-report series. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(4): 601.e5-7.

15 Motov S, Mai M, Pushkar I, Likourezos A, Drapkin J,Yasavolian M, et al. A prospective randomized, double-dummy trial comparing IV push low dose ketamine to short infusion of low dose ketamine for treatment of pain in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(8):1095-100.

16 Sheehy KA, Lippold C, Rice AL, Nobrega R, Finkel JC,Quezado ZM. Subanesthetic ketamine for pain management in hospitalized children, adolescents, and young adults: a singlecenter cohort study. J Pain Res. 2017;10:787-95.

17 Zempsky WT, Loiselle KA, Corsi JM, Hagstrom JN. Use of low-dose ketamine infusion for pediatric patients with sickle cell disease-related pain: a case series. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(2):163-7.

18 Uprety D, Baber A, Foy M. Ketamine infusion for sickle cell pain crisis refractory to opioids: a case report and review of literature. Ann Hematol. 2014;93(5):769-71.

19 Tawfi c QA, Eipe N, Penning J. Ultra-low-dose ketamine infusion for ischemic limb pain. Can J Anaesth. 2014;61(1):86-7.

20 Motov S, Drapkin J, Likourezos A, Beals T, Monfort R, Fromm C, et al. Continuous intravenous sub-dissociative dose ketamine infusion for managing pain in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19(3):559-66.

21 Klaess CC, Jungguist CR. Current Ketamine Practice: Results of the 2016 American Society of Pain Management Nursing Survery on Ketamine. Pain Manag Nurs. 2018;19(3):222-9.

World journal of emergency medicine2018年4期

World journal of emergency medicine2018年4期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Social attitude and willingness to attend cardiopulmonary resuscitation training and perform resuscitation in the Crimea

- Effect of sedative agent selection on morbidity,mortality and length of stay in patients with increase in intracranial pressure

- Utility of point-of-care musculoskeletal ultrasound in the evaluation of emergency department musculoskeletal pathology

- Accuracy of abdominal ultrasound for the diagnosis of small bowel obstruction in the emergency department

- Ultrasonographic assessment of paediatric ocular emergencies: A tertiary eye hospital based observation

- Estimating the weight of children in Nepal by Broselow, PAWPER XL and Mercy method