Social attitude and willingness to attend cardiopulmonary resuscitation training and perform resuscitation in the Crimea

Alexei Birkun, Yekaterina Kosova

1 Department of Anaesthesiology, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine, Medical Academy named after S. I. Georgievsky of V. I. Vernadsky Crimean Federal University; 295051, Lenin Blvd, 5/7, Simferopol, Russian Federation

2 Department of Applied Mathematics, Taurida Academy of V. I. Vernadsky Crimean Federal University; 295007, Prospect Vernadskogo, 4, Simferopol, Russian Federation

KEY WORDS: Cardiopulmonary resuscitation; Cardiac arrest; First aid; Training; Survey

INTRODUCTION

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is recognized as a significant public health problem throughout the world.[1–4]In North America and the European Union,the incidence of OHCA cases, attended by emergency medical services (EMS), is currently reported to be as high as 84–98 per 100,000 population-years, and survival is ranging from 30% to less than 5%.[3,5]Though little is known about the epidemiology of OHCA in most Eastern European countries, cardiovascular diseases constitute the leading cause of mortality in the Russian Federation[6]and Ukraine,[7]and recent data suggest high incidence of OHCA with low efficiency of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in the Crimea,[8]where the management of public health services has passed from Ukraine to Russia since 2014.

Without early intervention, the chance of survival from OHCA falls by 7%–10% per minute,[9]while the median interval for EMS arrival is 5–8 minutes.[10]Immediate bystander-initiated CPR and defibrillation are essential to improve survival in OHCA.[10]However,attitudes towards CPR and willingness to perform CPR vary widely between populations,[4,11,12]and yet,many communities[2,3,13]report low bystander CPR rates. Effective education of the general public on how to perform CPR properly may increase the number of people willing to undertake CPR in real life and improve survival, and training of lay people in CPR is currently acknowledged as a primary educational goal in resuscitation.[14]

In order to improve bystander CPR rates in the community, knowledge of current population’s training status, attitude, willingness and barriers to get training and perform CPR is necessary.[12]However, in the former USSR countries (including Russia and Ukraine),thus far no studies have investigated the proportion of general public that has undergone CPR training and their willingness to attempt CPR and attend CPR training.

This observational, descriptive, cross-sectional survey was aimed, as a case study, to investigate previous CPR training and knowledge, attitude and willingness to get trained in CPR and to perform CPR in the general population of the Crimea.

METHODS

Study sample

The survey was conducted from November 2017 to January 2018 in the territory of the Crimean peninsula,located on the northern coast of the Black Sea. The target population included 1.9 million permanent residents of the Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol aged≥18 years.[15,16]We used a quota sampling approach to reflect population age, gender, geographic distribution(northern, western, southern, eastern, central Crimea and Sevastopol) and place of residence (urban/rural)according to the latest population census.[15,16]The sample size needed to reflect the target population with a ±5%margin of error at a 95% confi dence level was calculated as 384 using the Cochran formula.[17]

Questionnaire

The structured 26-item questionnaire was designed for personal interview. Initial section of the questionnaire asked about previous CPR training, reasons for not attending any CPR training, willingness to learn CPR and potential motivating factors for future training.Further, willingness to attempt CPR in real life was evaluated using a 5-point numeric rating scale (from 1 –defi nitely will not do CPR to 5 – defi nitely will do CPR),and potential barriers to perform CPR on a stranger or a friend/relative were inquired with multiple-choice questions. General CPR knowledge was fi rst self-rated by respondents on a 5-point scale (from 1 – no knowledge to 5 – very good knowledge). Further, two openended questions were asked to assess the participants’knowledge of CPR in terms of hand placement and rate for chest compressions. The experience of real-life cardiac arrest, participants’ health status and existence of health problems in relatives were also queried. The ending section of the questionnaire collected demographic data,including age, marital status, educational background,occupation and total monthly income.

The questionnaire was pilot-tested for readability and unambiguity in a group of 10 lay persons, and minor corrections were made to improve. To assess testretest reliability, the questionnaire was administered two times to 21 persons with an interval of 14 days,and the reliability was considered as good (Cronbach’s alpha=0.89; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.64–0.96).The questionnaire was not tested for internal consistency because the individual items were not expected to be measuring similar or directly related constructs.

Interviews were conducted personally by 10 trained interviewers in public places. Potential respondents were asked if they would like to answer a series of questions related to their attitude and willingness to provide first aid to a victim in cardiac arrest. There was no conflict of interest between the respondents and the survey. All respondents provided their informed verbal consent for participation. The institutional review board reviewed the questionnaire and approved this study.

Statistical methods

We first performed descriptive statistics for the respondents’ characteristics. The characteristics were then compared with regard to previous CPR training status, CPR knowledge, willingness to attend CPR training and to perform CPR by chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The strength of association was measured using the Cramér’s V or phi coefficient. The following values were used to interpret the measures of association: 0.1 – small,0.3 – moderate, 0.5 – large.[18]Further, variables with confirmed association (P<0.05) were included in a binomial logistic regression analysis to determine the set of factors associated with previous resuscitation training,willingness to attend training and willingness to attempt CPR, and results were expressed as odds ratios (OR) and 95% CI. Variables considered collinear were excluded.P-values <0.05 represented statistically significant differences. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 (IBM Corporation, USA).

RESULTS

A total of 459 questio nnaires were administered by interviewers. Eight questionnaires contained incomplete or contradictive answers and were excluded. There were only 25 cases of refusal to participate in the survey or early interruption of the interview, producing the response rate of 95%. Seventy five questionnaires were oversampled and, being considered as a duplication of respondents’ demographic categories, were excluded from analysis in order to preserve representativeness of the population under study. Finally, 384 original and correctly completed questionnaires were selected for the analysis.

Participants

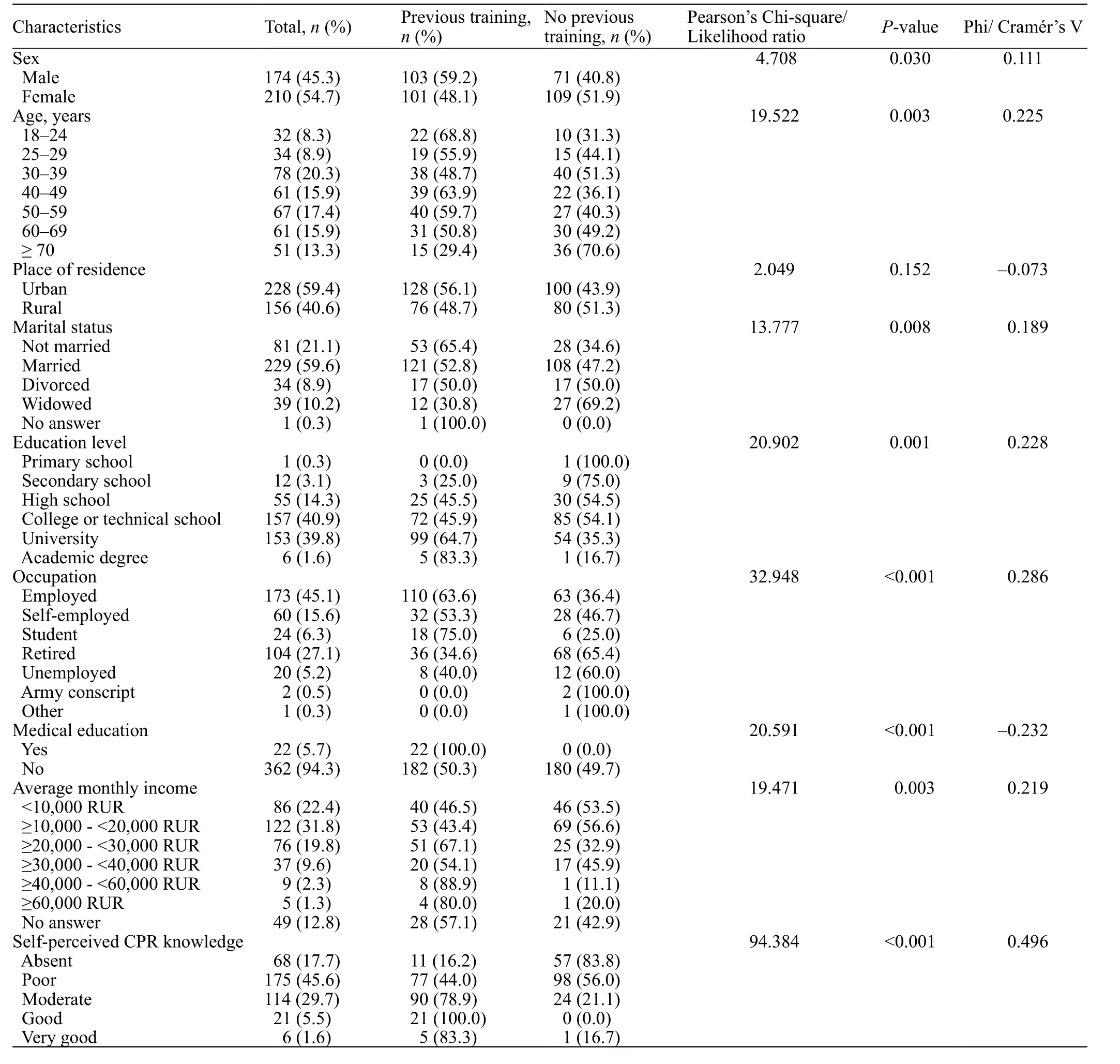

The distribution of respondents by socio-economic and demographic characteristics is presented in Table 1. Among the respondents, 45% were male. Urban population accounted for 59% of the survey participants.Most respondents were married (60%), with college/technical school education or higher (82%), employed or self-employed (61%). Six percent (n=22) hadprofessional medical education. The monthly income was most commonly (32%) reported to be ≥10,000 - <20,000 rouble (RUR).

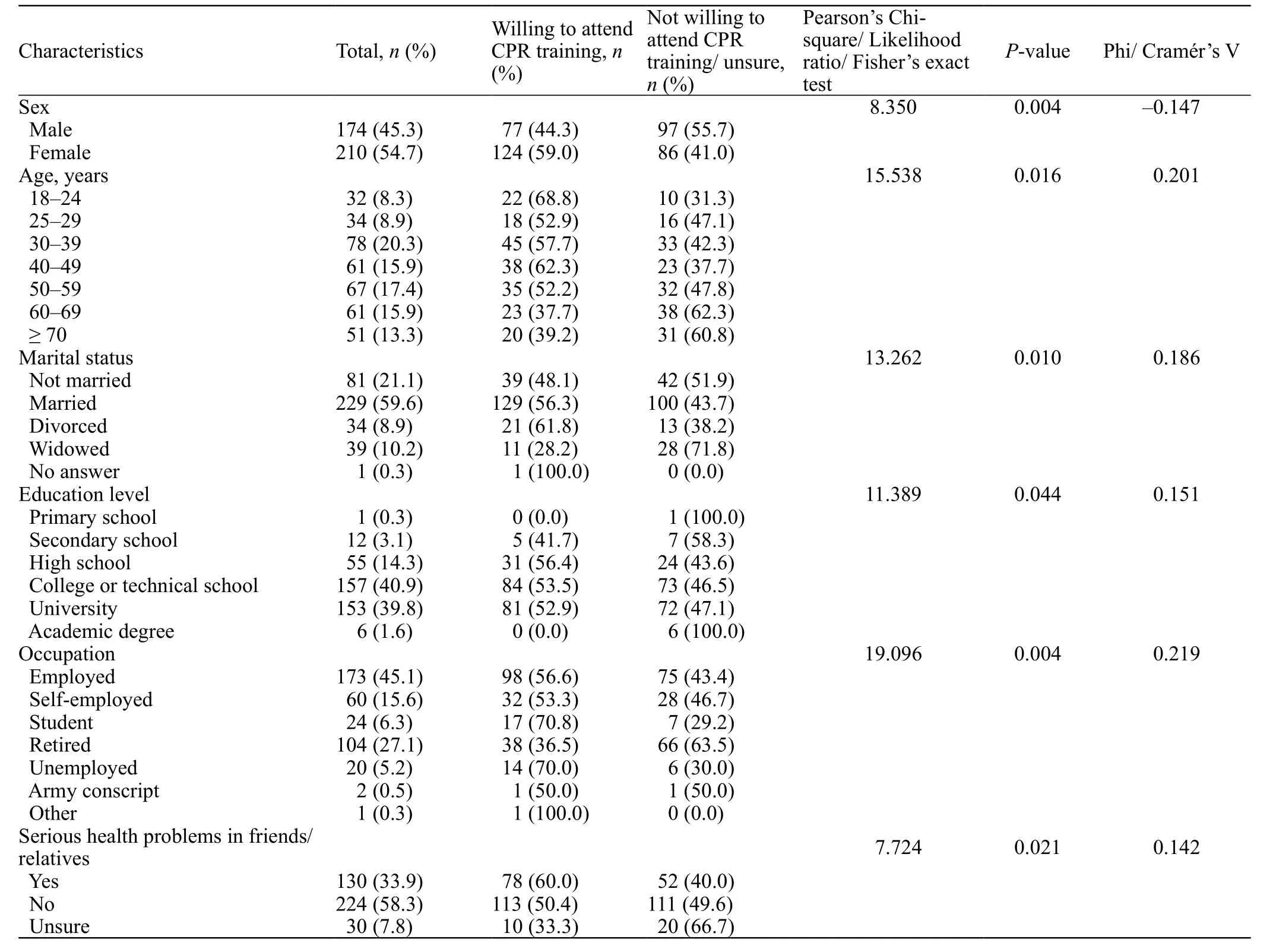

Table 1. Respondents’ characteristics and univariate association with previous CPR training

Approximately 1% estimated their own health as very poor, 6% – as poor, 47% – satisfactory, 40% –good, and 6% – very good. Thirty four percent (n=130)confirmed that their relatives or friends currently have serious health-related problems.

About 78% (n=298) respondents had no experience of real-life cardiac arrest situations. Among the respondents who had previously witnessed cardiac arrest(n=81), 77% (n=62) were bystanders not participating in the CPR attempt and 23% (n=19) participated in providing CPR in real life. Out of those who witnessed cardiac arrest, 28% (n=23) stated the victim was their loved one, and 5 of 23 (22%) attempted CPR.

Previous CPR education

Of the respondents, 53% (204/384) reported previous resuscitation training (chest compressions or rescue breathing) (Table 1). All respondents having professional medical education were previously trained in CPR.

Based on univariate analysis, the status of previous CPR training was associated with sex, age, marital status,educational level, occupation, medical background and monthly income (small to moderate association), but independent from the place of residence (urban vs. rural)(Table 1).

In logistic regression model, males (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.1–2.6), those having had a university education (OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.5–3.8), employed (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.6–4.4) and students (OR 6.9, 95% CI 2.5–19.2) were found to be predictive of previous training in CPR.

Fourteen percent (n=28) of trained respondents received their last training less than 6 months before the survey, 10% (21) were trained 6–12 months ago, 18%(36) 1–5 years ago, 54% (110) more than 5 years ago, and 4% (9) were unable to recall time of their last training.

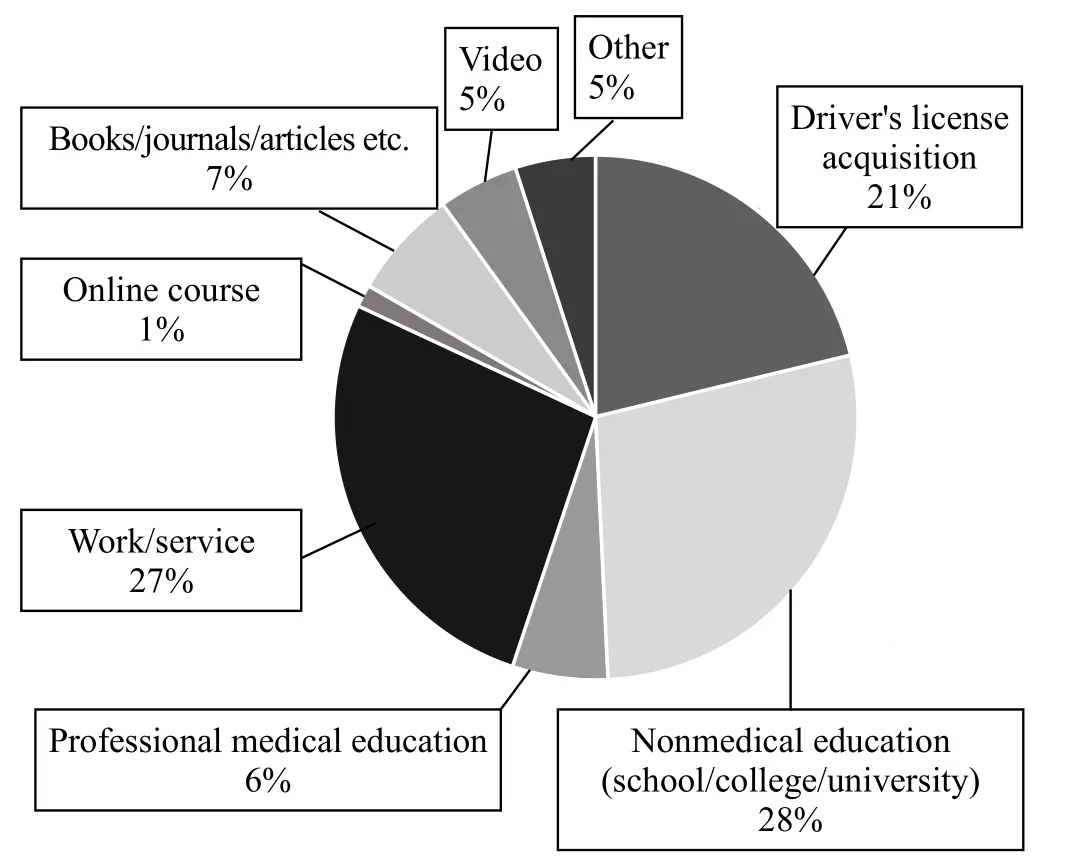

Figure 1 shows the distribution of previous trainings depending on the type.

Forty four percent (n=89) of trained respondents attended one CPR course, 22% (46) attended two courses, 20% (41) 3–5 courses, and 11% (22) attended more than 5 courses. The remainder of the respondents(3%) reported forms of training, other than a course(internet, videos, books, etc.).

Forty seven percent (180/384) of respondents had no previous CPR training. The most common reasons for not taking CPR training were that the respondent never thought about the need to go for training (51%) or did not know where to attend the training (28%). About 10%reported they have always thought they have no need of CPR training. Reluctance to spend money or time was less common (1.4% and 4.6%, respectively). Occasional voluntarily reported reasons for not being trained in CPR (“other”, 5.5%) included “training not offered”, “no favourable opportunity”, “fear” and “reluctance to study”.

CPR knowledge

Self-perceived respondents’ CPR knowledge was reported as follows: “absent” – 17.7% (68/384), “poor” –45.6% (175), “moderate” – 29.7% (114), “good” – 5.5%(21), “very good” – 1.6% (6).

There was a strong relationship between the selfperceived knowledge level and previous training status:those who rated their knowledge as “moderate” and above were mostly previously trained (Table 1). With that, there was no association of self-perceived CPR knowledge level with the number of attended CPR courses, the time of last training or willingness to attend CPR training (P>0.05).

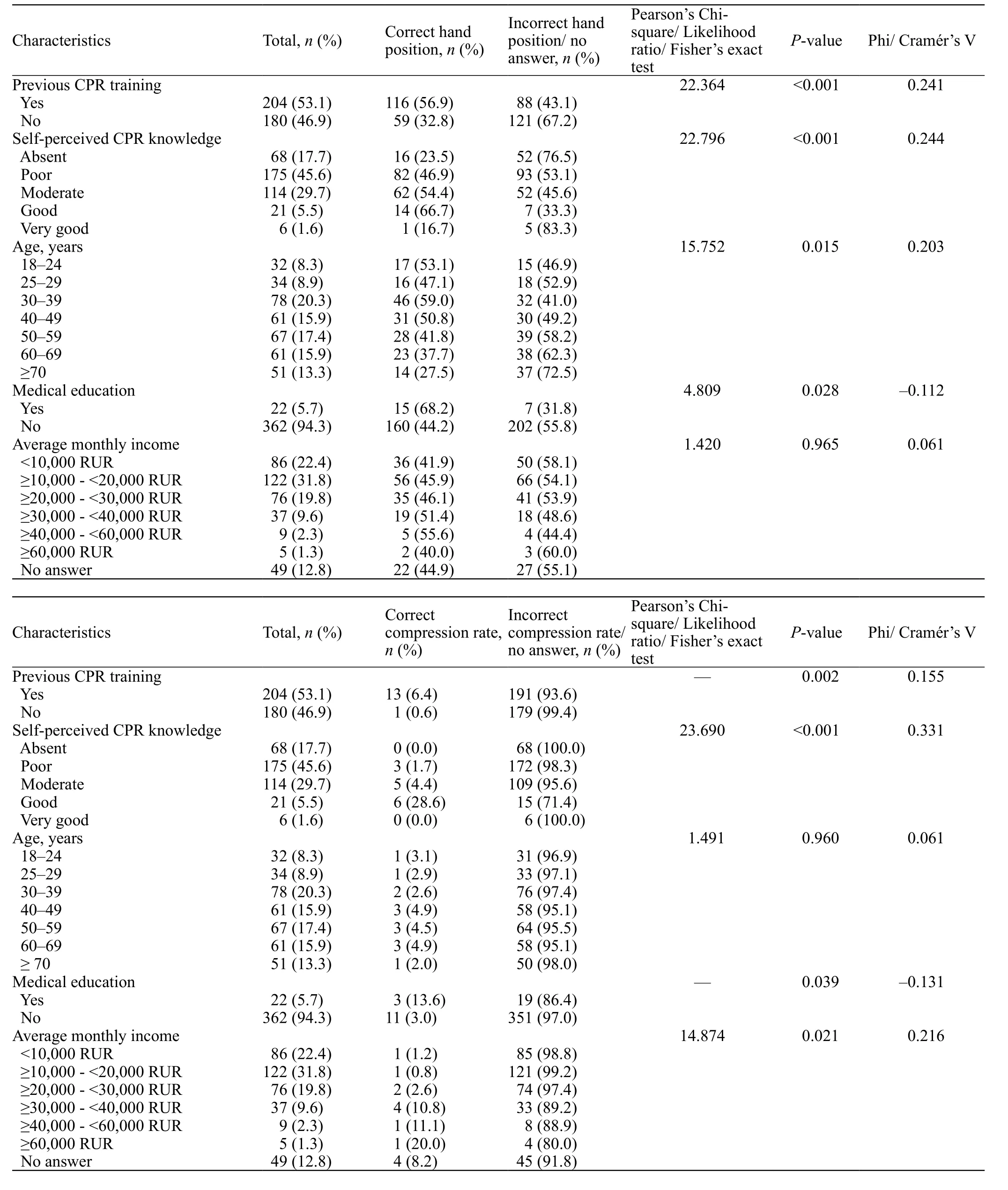

Almost half of the respondents (46%) correctly indicated site for chest compressions as lower half of the sternum in the middle of the chest, whereas more than 38% respondents selected left side of the chest. Among those who provided correct answer, 66% were previously trained in CPR. Correct answering was associated with previous CPR training, higher level of self-perceived CPR knowledge (excepting “very good” knowledge group, where only one out of 6 answered correctly),lower age and medical education, but independent from the number of attended courses, timing of last training,or other demographic characteristics (P>0.05) (Table 2).

Figure 1. Distribution of prior CPR training by type.

Only 14 out of 384 respondents (3.6%) specified the rate of chest compressions in compliance with the currently recommended range of 100–120 per minute.[10]Correct answering to this question was associated with previous CPR training, higher level of self-perceived CPR knowledge (except in the “very good” knowledge group, where null out of 6 answered correctly), medicaleducation and higher monthly income, but independent of the number of attended courses, timing of last training,or other demographics (P>0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2. Respondents’ characteristics associated with CPR knowledge in univariate analysis

Among the healthcare professionals, 68% and 14%provided correct answers as of hand placement and rate for chest compressions, respectively.

Attitude and willingness to attend CPR training

Fifty two percent (201 of 384) respondents provided an affirmative answer to the question of whether or not they wish to attend CPR training, 31% had no interest in training, and 17% were unsure of their willingness.

By univariate analysis, willingness to attend CPR training was independent (P>0.05) of the previous training status, quantity of attended courses, timing of the last training, self-perceived level of CPR knowledge,true knowledge of hand position and rate of chest compressions, experience of real-life cardiac arrest, selfperceived health status, place of residence (urban/rural),presence of medical education or a monthly income, but exhibited small to medium association with sex, age, marital status, educational level, occupation, and existence of serious health-related problems in relatives or friends (Table 3).

Logistic regression analysis showed females (OR 2.3,95% CI 1.5–3.6), persons aged below 60 (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.2–3.2) and non-widowed (OR 3.0, 95% CI 1.3–6.8)being more likely to be willing to learn CPR.

The distribution of motivating factors for attending CPR training among all respondents is presented in Figure 2.

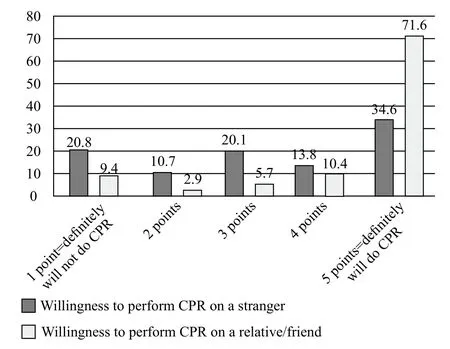

Attitude and willingness to perform CPR

Seventy nine percent (304 of 384) respondents expressed at least some willingness to perform bystander CPR on a stranger in real life, and 91% (348 of 384) were willing to attempt CPR on their friend or relative (Figure 3).

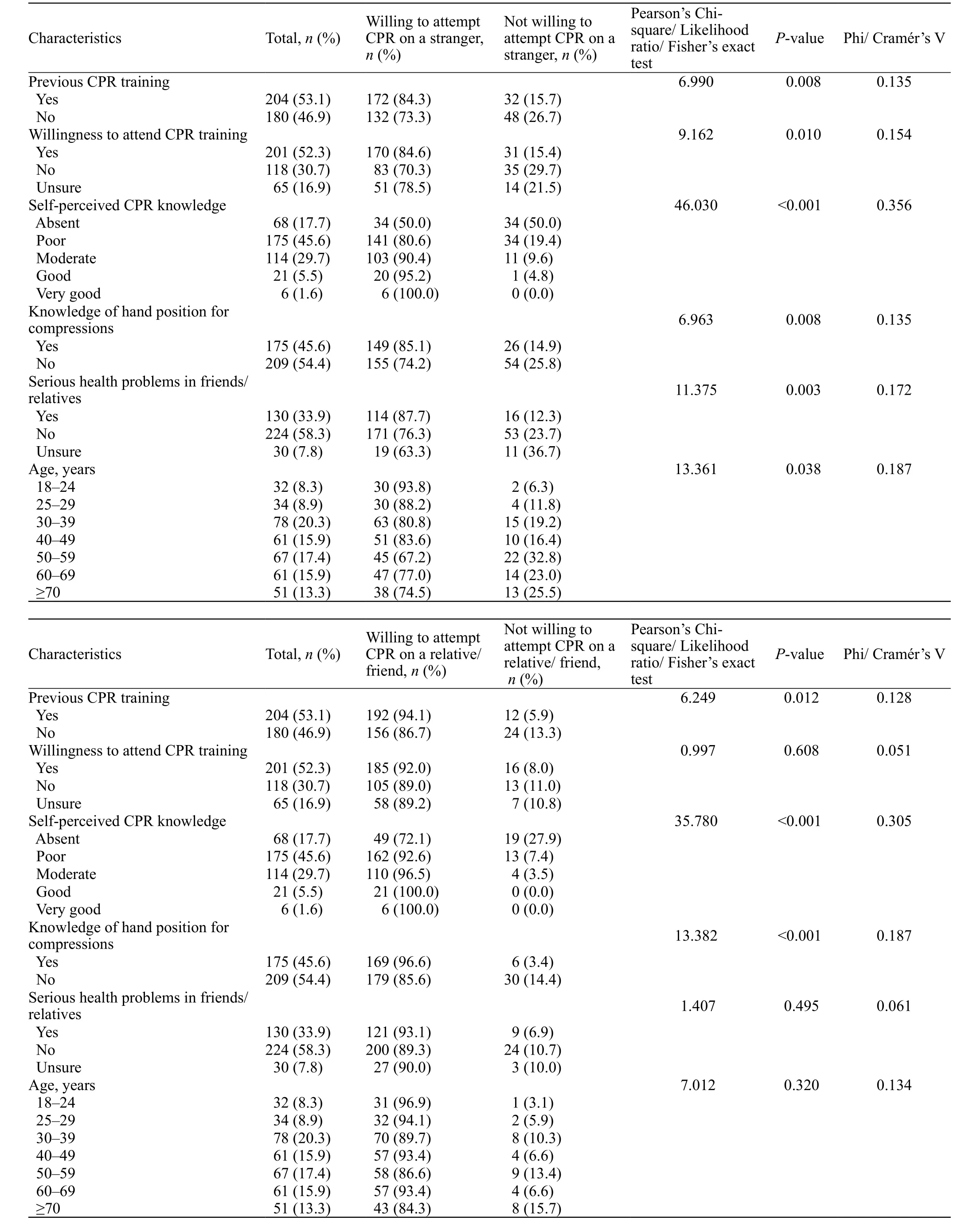

The willingness to perform CPR was positively associated with previous CPR training and self-perceived level of CPR knowledge, but independent from the number of attended courses, timing of last training,experience of cardiac arrest in real life, self-perceivedhealth state, sex, place of residence (urban/rural), marital status, educational level, occupation, medical education or monthly income (P>0.05; Table 4).

Table 3. Respondents’ characteristics associated with willingness to attend CPR training in univariate analysis

Figure 2. Motivations for respondents to attend CPR training.

Figure 3. Percentage distribution of respondents according to their willingness to do CPR in real life.

Whereas younger respondents were more willing to attempt CPR on a stranger, the willingness to provide CPR on a loved one was independent from age. The willingness to perform CPR on a stranger showed a relationship with the willingness to attend CPR training and existence of serious health-related problems in relatives/friends. Those respondents who reported correct hand position for chest compressions expressed higher willingness to attempt CPR on either strangers or loved ones, but there was no such association for the knowledge of correct compression rate.

In binomial logistic regression, willingness to attempt CPR on a stranger was found to be predicted by willingness to learn CPR (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.1–3.4), at least poor self-perceived knowledge of CPR (OR 6.9,95% CI 3.8–12.7) and serious health problems in friends/relatives (OR 2.8, 95% CI 1.4–5.3). The willingness to perform CPR on a loved one significantly correlated with at least poor self-perceived knowledge of CPR (OR 5.4, 95% CI 2.6–11.3) and the true knowledge of hand position for chest compressions (OR 3.5, 95% CI 1.4–8.8).

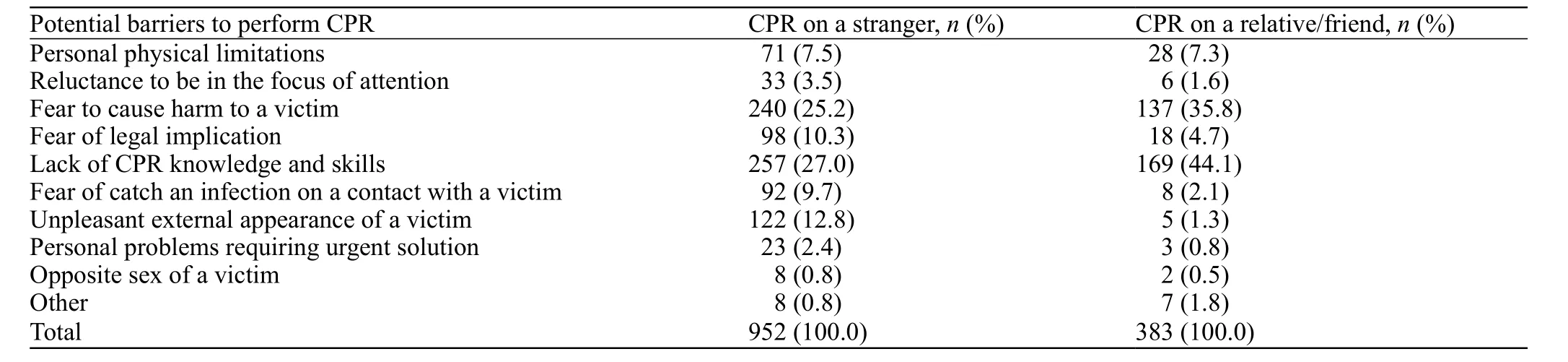

The potential barriers to attempt CPR were much more commonly reported when hypothesizing cardiac arrest in a stranger than in a loved one (952 vs. 383,respectively) (Table 5). The fear to cause harm to a victim and lack of CPR knowledge and skills were the commonest barriers to perform CPR. Further, when several barriers were reported, fear to cause harm or lack of CPR knowledge/skills were most frequently perceived as the strongest barrier to attempt resuscitation (32% and 34%, respectively, for CPR on a stranger, 20% and 29%for CPR on a friend/relative). Overall, 10% and 46%respondents reported no barriers when supposing CPR attempt on a stranger or on a loved one, respectively.

Reporting lack of CPR knowledge and skills as a barrier to attempt CPR on a stranger was positively associated with willingness to attend CPR training (Pearson’s chi-square:9.884; P=0.002; phi=0.160) and negatively associated with previous CPR training (28.431; P<0.001; phi=–0.272),self-perceived level of CPR knowledge (62.720; P<0.001;Cramer’s V=0.404) and willingness to perform CPR on a stranger (5.103; P=0.024; phi=–0.115).

Table 5. Distribution of responses to the multiple-choice questions querying potential barriers to attempt CPR in real life

Table 4. Respondents’ characteristics associated with willingness to perform CPR in univariate analysis

DISCUSSION

To the authors’ best knowledge, this is the fi rst study investigating current CPR training status, willingness to attend CPR training and to perform CPR in the selected population among 15 European and Asian countries of the former Soviet Union.

The results show that more than a half (53%) of adult citizens of the Crimea was previously trained in CPR.The proportion is higher than reported for the general population in Sweden (45%),[11]USA (42%),[19]Turkey(40%),[20]Japan (35%),[12]Ireland (28%),[21]or China(26%),[4]but lower than for Poland (73%),[22]Slovenia(69%)[23]or Western Australia (64%).[24]

Despite the relatively high percentage of trained respondents, less than a quarter received their training within one year prior to the survey, and out of those who attended courses, almost half were trained on a single occasion. The majority passed CPR training at workplace, when gaining education or acquiring a driver’s license. Females, elderly, widowed, retired,unemployed and those having lower income are trained less, whereas unmarried, those with university education,involved in the workforce and students are having higher chances to be trained.

According to previous surveys, the most common reasons for not being trained in CPR are that the respondents were unaware that such training existed or did not know where to attend courses (47%–55%),whereas lack of time (1%–33%), no interest in training(11%–21%) or undesirable expenses (1%–9%) are reported less frequently.[4,11,21,25]Our results show that most untrained respondents had no thoughts about the need to go for training, suggesting low awareness as of the relevance of CPR training and bystander CPR among the lay people, along with insufficient training opportunities.

Our study showed poor knowledge of CPR in the studied population. Despite the previously trained respondents demonstrating better knowledge and selfconfi dence, the rates of correct answering are alarmingly low, with healthcare professionals to a great extent showing incompetence alongside with lay people.Whereas the level of self-perceived CPR knowledge generally correlated with correct answering to the CPR questions, those respondents who declared their knowledge to be very good were overestimating their own expertise. Notably, true knowledge was independent from the number of attended courses and timing of last CPR training. The proportions of correct answering as of the proper site and rate of chest compressions reported for other countries are 34% and 6%, respectively, in USA,[19]38% and 1% in Slovenia,[23]52% and 18% in Turkey,[20]compared with 46% and 4% in our survey.

Approximately half of the respondents wish to learn CPR, regardless of previous training, knowledge of CPR or medical background. A similar rate was reported for Sweden, where 50% wished to be trained in CPR, 29%were unsure and 22% had no interest in learning CPR.[11]The top three motivators to attend CPR training were awareness of importance of CPR training, potential health problems in relatives/friends and free-of-charge training. Lower interest in learning CPR was revealed in males, elderly, widowed and retired.

The extent of declared readiness to attempt CPR on a stranger and on a relative or friend is high (79%and 91%, respectively) and comparable to that in China(76% and 99%, respectively).[4]By comparison, the willingness to perform CPR on a stranger or on a loved one was reported to be 7% and 13%, respectively, for the Japanese population,[12]32% and 55% for Korea,[26]and around 50% and 80% for the USA.[1]With that,in a questionnaire survey of Queensland’s population(Australia), 55% respondents were reported to be“extremely likely” to attempt CPR on an average person and 6% were “extremely unlikely” to perform bystander CPR,[27]compared with 35% and 21% in our study.

The primary reasons that impeded the respondents’readiness to attempt CPR were lack of CPR knowledge and skills, and fear to cause harm to a victim. The same barriers were reported as common in other studies.[1,4,23]Fear of being sued is less prevalent in the studied population(10%) compared to the USA (22%)[1]or China (53%),[4]but higher than reported for the Australian community(2%).[27]About 46% did not perceive any barriers to perform CPR on a loved one that is consistent with high rates of readiness to attempt CPR in the Crimean population. As for the CPR on a stranger, 10% stated no barriers compared to 63% reported for the Australian lay public.[27]

Our study revealed higher willingness to perform CPR on a loved one, than on a stranger – the percentage of those definitely willing to do CPR was two times higher for CPR on a relative/friend. This is in agreement with the other studies.[1,4,12,27]

The association of willingness to perform CPR with having been trained in CPR was demonstrated by numerous studies.[1,12,13,19,27]Some of them revealed rising willingness to attempt CPR with an increasing number of CPR training sessions attended.[24,26]Further,those trained more recently are more likely to attempt CPR on a loved one or a stranger.[13,24,26,27]Although the previously trained were more willing to perform CPR,we found no association with the number or timing of last training. Moreover, willingness to perform CPR was found to be independent of the medical background of the potential rescuer.

Elderly persons are known to be significantly less trained and less interested in learning CPR.[11,13,21,22]Also,older people tend to be less willing to provide CPR.[1,24,26]Our study revealed a similar association, excepting willingness to perform CPR on a loved one that was independent from age. With that, the older population seem to be at the highest risk to witness a cardiac arrest:most victims are in their late sixties, collapsing at home and a half are witnessed by a family member or friend who is usually over the age of 55.[28]

Being trained more commonly than females,males seem to be less willing to attend CPR training,whereas knowledge of CPR and willingness to attempt resuscitation have no sex differences.

The marital status was found to be associated with previous training status and willingness to learn CPR,but unrelated with willingness to perform CPR in real life. Almost two thirds unmarried respondents are trained in CPR, but only a half reported willingness to attend the training. Married and divorced are trained fi fty-fi fty, but predominantly willing to learn CPR. Widowed, being mostly aged above 60 (82%), are usually untrained and not willing to attend CPR training.

Axelsson et al[11]revealed that the rural Swedish population have participated in CPR courses more than those living in urban areas, while the latter were more willing to learn CPR.[11]Other studies showed no difference between city and country dwellers in their willingness to perform bystander resuscitation. We found no association of the place of residence (urban/rural) with previous CPR training, willingness to attend training or attempt CPR in real life.

It has been previously shown that people who performed CPR in a real-life situation of cardiac arrest are signifi cantly more likely to give resuscitation both to a loved one or a stranger.[12,13,24]In our study, willingness to perform CPR or to attend CPR training was independent from experience of cardiac arrest in real life.

There was no association of respondents’ selfperceived health state with willingness to learn CPR or to attempt resuscitation. However, being the second most common motivator to learn CPR, existence of serious health-related problems in relatives or friends was associated with higher willingness to attend CPR training. It is noteworthy, that those who reported serious health problems in loved ones were about three times more likely to attempt CPR on a stranger, but this factor had no influence on the willingness to attempt CPR on a relative or friend. Having friends with heart diseases was previously reported as a predictor of willingness to attempt CPR.[12]

We found higher educational level to be associated with higher rate of CPR training and higher willingness to learn CPR. Those respondents with an education lower than high school are least trained and motivated to learn.Whereas willingness to perform CPR was previously shown to be associated with higher educational level,[12,26]this was not the case in our study.

Both previous training status and willingness to be trained revealed a relationship with occupation.Employed/self-employed and students are about 3- and 7-times, respectively, more likely to be trained than other occupational groups, and mostly willing to learn CPR.The retired are predominantly untrained and unwilling to be trained, whereas the unemployed are more commonly willing to learn CPR, but usually untrained. When compared with other studies,[12,27]willingness to attempt CPR on a stranger or a loved one was independent from the occupation. Although higher monthly earnings were found to be associated with higher rate of previous training, there is no relation of income with willingness to be trained or to attempt CPR on a victim.

Yet, there is no organized nationwide system of community CPR training in Russia,[29]nor in Ukraine,[30]the two states responsible for the public health management in the Crimea since the collapse of the USSR in 1991. The educational opportunities for the population are mostly limited to compulsory but low quality CPR training during driver’s license acquisition,and occasional CPR courses, apparently not covering all population categories.[29–31]Further, there are no local institutions, organizations or authorities regulating or offering CPR training for the Crimean lay public. Recent epidemiologic study in a population of administrative centre of the Crimea revealed the incidence of EMS-attended OHCA to be as high as 674 per 100,000 population-year, with less than 3% victims receiving bystander CPR (26.5% of all attempted resuscitations)and a null survival.[8]The survey results show that less than a quarter of bystanders who witnessed cardiac arrest in real life were actually participating in the CPR attempt. Taken together, these findings emphasise an urgent need to increase the number of adequately trained first responders among the lay people by implementing large-scale continued community training programs with regular refresher courses, and further efforts should be made to increase the access of the least trained social strata to the CPR training.

Limitations

We acknowledge the possible inevitable selection bias, with those who agreed to participate potentially having higher interest and better understanding of CPR,compared to those who refused. We cannot exclude the possibility of inappropriate recall as of the number and timing of previous resuscitation training. Our survey has not accounted for ethnic categories of the population.The survey has geographic limitations, and a national survey may provide a more representative picture. It is possible that respondents provide misleading answers,potentially affecting the reliability of the survey results.Further, the reported willingness to attempt CPR may not refl ect one’s actual ability to perform CPR in a stressful real-life cardiac arrest situation.

CONCLUSIONS

There is a need for increasing community CPR training and retraining, and enhancing awareness and motivation to learn CPR in the Crimean population.Almost a half had never learned CPR, and among the previously trained, the vast majority received their training more than one year ago. Not trained were mostly never thinking about the need to go for training or did not know where to attend. While the lay people declare relatively high willingness to attempt resuscitation,knowledge of CPR is generally poor. The lack of CPR knowledge and skills constitute the main barrier to perform CPR in real life, showing the potential to increase the number of people willing to attempt CPR by way of public education. Persons aged above 60,those with educational level lower than high school,the widowed and the retired are mostly untrained and unwilling to learn CPR. Females and unemployed are mostly untrained, but willing to be trained. Targeting these groups for training may increase the rates of bystander CPR in the community. The methodology and results of the survey may be used as a reference point for similar studies in the rest of the post-Soviet area.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dantanarayana Visith Risira for editing the text in English language.

Funding:This study did not receive any funding.

Ethical approval:The institutional review board reviewed the questionnaire and approved this study.

Competing interests:The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributors:AB determined the concept of the study and was a major contributor to the study design, data collection, data analysis and manuscript preparation. YK assisted in data acquisition and statistical analysis, in writing the manuscript and revising the article. All authors read and approved the fi nal manuscript.