Misdiagnosed Aortic Intramural Hematoma and the Role of Intravascular Ultrasound Imaging in Detection of Acute Aortic Syndrome: A Case Report

Niya Mileva, MD , Dobrin Vassilev, MD, PhD , Robert Gil, MD, PhD and Gianluca Rigatelli, MD, PhD

1 Cardiology Clinic, “ Alexandrovska” University Hospital, Medical University of So fia, “ St. George So fiiski” Str. 1, 1431 So fia,Bulgaria

2 Mossakowski Medical Research Centre, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland; and Department of Invasive Cardiology, Central Clinical Hospital of the Ministry of the Interior, Warsaw, Poland

3 Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Endoluminal Interventions, Section of Adult Congenital Heart Interventions, Rovigo General Hospital, Rovigo, Italy

Introduction

Acute aortic syndrome (AAS) is a term that refers to the acute presentation of potentially life-threatening abnormalities of the aorta, including classic aortic dissection, aortic intramural hematoma (AIH), and penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer (PAU) [ 1, 2]. These diseases may present with a variety of symptoms and mimic other conditions, such as acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolism, and pericarditis.However, the diagnosis of AAS has many potential difficulties. Because of the similar clinical manifestations, there is a high risk of misdiagnosis.

The most commonly used imaging studies include transthoracic echocardiography, transesophageal echocardiography, and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) [ 3]. Although conventional noninvasive imaging techniques have high sensitivity and speci ficity in the diagnosis of AAS, they still have some limitations in differentiating the particular forms of AAS. Here, we present a case example in which intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) imaging could be useful in this aspect.

Case Presentation

A 67-year-old woman with a history of essential hypertension and stage 4 chronic kidney disease presented to the emergency department with sudden chest pain at rest. On admission she was stable, with blood pressure of 130/90 mmHg in both hands, heart rate of 80 beats per minute, and respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute. Electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm, without any ST-segment abnormalities. Laboratory results were unremarkable, with the levels of cardiac enzymes within reference ranges. However, D-dimer level was elevated at 1.78 mg/L (the reference range is less than 0.55 mg/L).

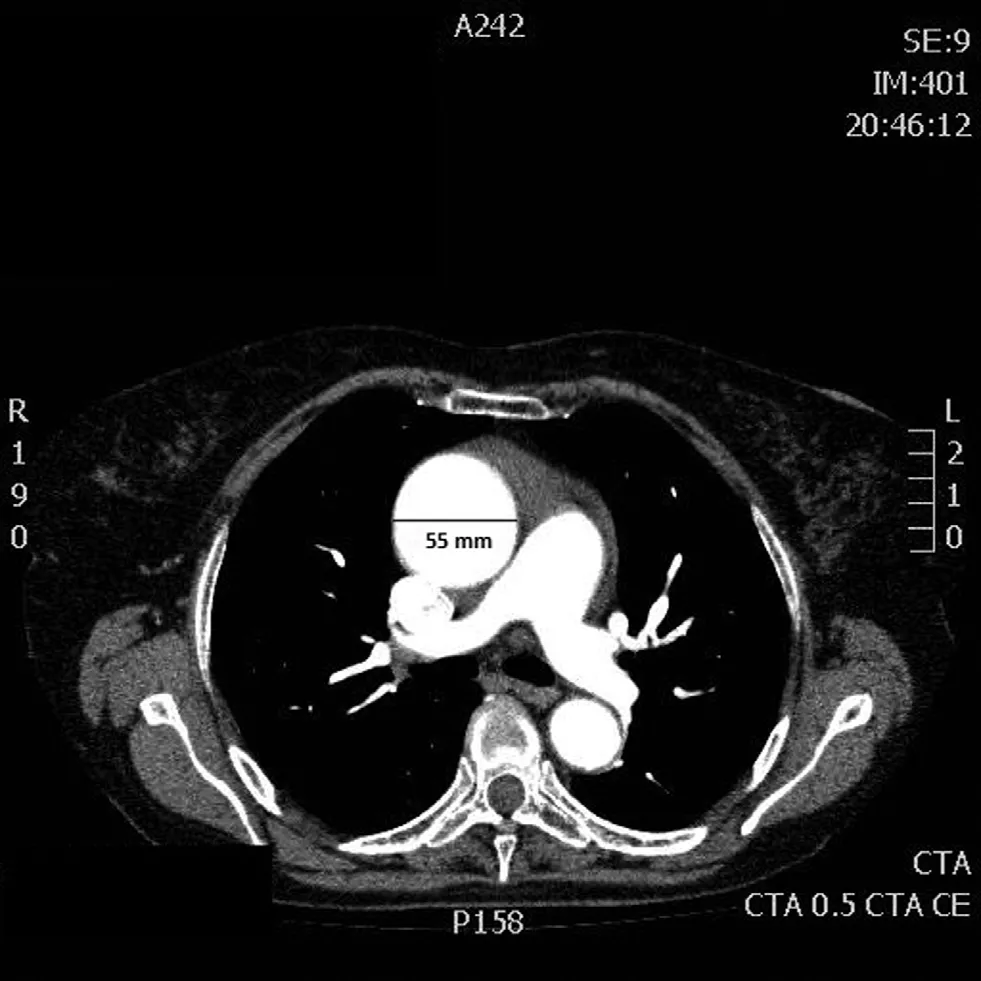

Widened mediastinum and abnormal aortic contour were found on chest radiography. The initial transthoracic echocardiography showed normal systolic function, ejection fraction of 57%, and normal kinetics of the left ventricle. However, a dilated ascending aorta with a maximum diameter of 42 mm was found. Moderate pericardial effusion was registered, without any signs of cardiac tamponade or compression of the cardiac chambers.Considering the patient’ s symptoms, we decided to perform contrast-enhanced CT for better visualization of the aorta and for exclusion of AAS. The scan con firmed the aneurysm of the ascending aorta,with a maximum dilation of 55 mm at the level of the bifurcation of the pulmonary artery and no signs of aortic dissection, AIH, or PAU (see Figure 1 ).

To exclude possible acute coronary syndrome,we decided to perform percutaneous coronary angiography. The study did not reveal any signi ficant coronary artery disease. During the procedure, considering the persisting symptoms of the patient, we discussed if IVUS imaging would be useful for better visualization of the underlying lesion of the aorta.

We used an 8.5 F, 20 MHz Visions PV probe(Volcano Philips, USA). Optimal ultrasound visualization of the diseased aorta was accomplished by our placing the transducer in the distal part of the vessel and slowly withdrawing it. As a result, localized AIH of the ascending aorta was registered, with maximum thickening of the aortic wall of 15 mm (see Figure 2 ).

Figure 1 Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography Revealing Dilation of the Ascending Aorta of 55 mm.

Figure 2 Intravascular Ultrasound Image.

Consequently, the patient was promptly transferred to the cardiac surgery department. The intraoperative finding was a dilated ascending aorta with localized intramural hematoma into the aortic wall. Aortic reconstruction was performed, and the patient recovered, with an uneventful postoperative period, and was discharged 10 days after the operation.

Discussion

AIH belongs to AAS, as do PAU and aortic dissection. These conditions are different in their pathogenesis and clinical signs; hence they require different therapeutic approaches [ 4]. Whereas in classic aortic dissection direct flow communication occurs through a primary intimal tear and blood flow propagation creates a second blood- filled channel within the wall, intramural hematoma occurs as a bleeding into the aortic wall as a consequence of rupture of the vasa vasorum in the medial wall layers [ 5, 6]. In AIH the hemorrhage occurs in the absence of initial intimal disruption or a false lumen.

Thus the diagnosis of AIH has many potential difficulties. Conventional noninvasive imaging techniques such as transthoracic echocardiography, transesophageal echocardiography, and CT are useful for detection of intimal flap or false lumen in classic aortic dissection. However, they often fail to identify AIH or PAU, where the lesion may be not so distinct [ 2]. IVUS imaging is a method that has a safe pro file and enables additional evaluation of the lesions of the aorta. Information derived from this examination can particularly aid in differentiating the speci fic forms of AAS. It was used in a patient with aortic dissection for the first time in 1990 by Weintraub et al. [ 7]. Since then, several studies with IVUS imaging of the aorta have been performed [ 8, 9].The role of IVUS imaging in diagnosis of AIH and PAU is to be further established.

Conclusion

In addition to classic aortic dissection and PAU,AIH is one of the causes of AAS. These conditions can be identical in their clinical manifestation, but they have important differences in diagnosis and management.

The case presented draws attention to the importance of clinical suspicion of AAS, with its particular forms, the value of using more than one imaging method, and the bene fits of IVUS imaging in the prompt diagnosis of this condition, which is essential to saving the life of patients.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no Conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Vilacosta I. Acute aortic syndrome.Heart 2001;85:365– 8.

2. Wei H, Schiele F, Meneveau N,Seronde MF, Legalery P, Caul field F, et al. The value of intravascular ultrasound imaging in diagnosis of aortic penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer. Eurointervention 2006;1(4):432– 7.

3. Von Kodolitsch Y, Csosz SK,Koschyk DH, Schalwat I, Loose R,Karck M, et al. Intramural hematoma of the aorta: predictors of progression to dissection and rupture.Circulation 2003;107:1158– 63.

4. Harris KM, Braverman AC, Eagle KA, Woznicki EM, Pyeritz RE,Myrmel T, et al. Acute aortic intramural hematoma: an analysis from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. Circulation 2012;126(11 Suppl 1):S91– 6.

5. Golledge J, Eagle KA. Acute aortic dissection. Lancet 2008;372(9632):55– 66.

6. Braverman AC. Acute aortic dissection: clinical update. Circulation 2010;122:184.

7. Weintraub AR, Schwartz SL,Pandian NG, Katz SE, Kwon OJ,Millan V, et al. Evaluation of acute aortic dissection by intravascular ultrasonography. N Engl J Med 1990;323:1566– 7.

8. Alfonso F, Goicolea J, Aragoncillo P,Hernandez R, Macaya C. Diagnosis of aortic intramural hematoma by intravascular ultrasound imaging.Am J Cardiol 1995;76:735– 8.

9. Svensson LG, Labib SB, Eisenhauer AC, Butterly JR. Intimal tear without hematoma: an important variant of aortic dissection that can elude current imaging techniques.Circulation 1999;99:1331– 6.

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications2018年1期

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications2018年1期

- Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications的其它文章

- Mitral Stenosis: A Review

- Functional Tricuspid Regurgitation and Ring Annuloplasty Repair

- Management of Mitral Regurgitation in a Patient Contemplating Pregnancy

- An Asymptomatic Patient with Severe Mitral Regurgitation

- Clinical Evaluation of a Patient with Asymptomatic Severe Aortic Stenosis

- Low-Gradient, Low Ejection Fraction SevereAortic Stenosis: Still a Management Conundrum