Management of Mitral Regurgitation in a Patient Contemplating Pregnancy

Yee-Ping Sun, MD and Patrick T. O’ Gara, MD

1 Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’ s Hospital, Harvard Medical School,Boston, MA, USA

Clinical Vignette

A 35 year-old woman seeks advice regarding a planned pregnancy. She has known of a heart murmur since she was 10 years old. She is physically active, but during the past 3 months has been unable to keep up in her exercise class. She reports not having orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea,or edema.

Physical examination: pulse rate of 60 per minute and regular; blood pressure of 110/73 mmHg; no jugular venous distention, carotid upstrokes normal;apical, holosystolic grade 3/6 murmur radiating to the axilla; no diastolic murmur audible; no edema.

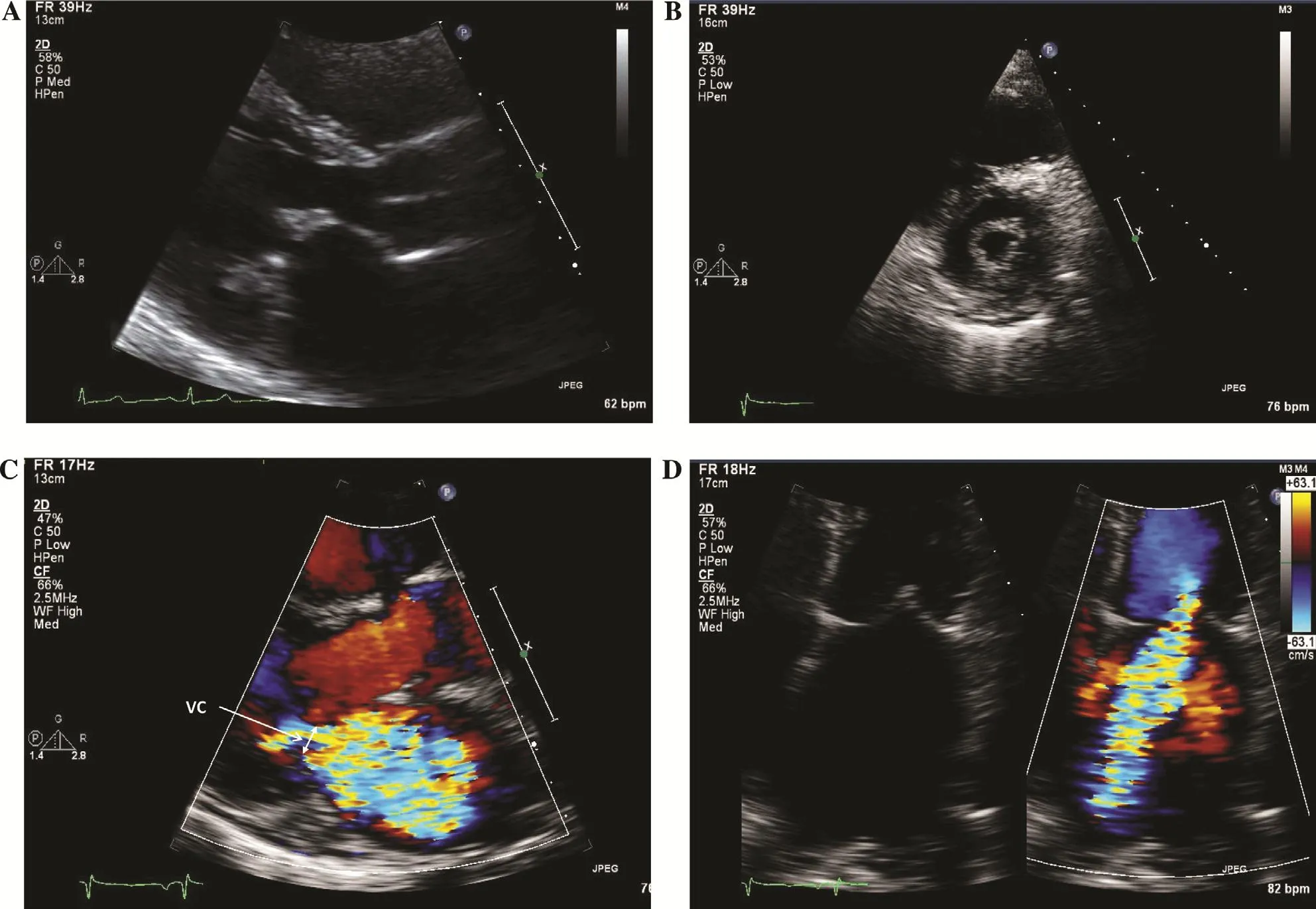

Transthoracic echocardiogram: left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 60%; left ventricular end-systolic dimension (LVESD) of 40 mm, left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) of 110 mL/m2; left atrial volume of 40 mL/m2; mitral valve with rheumatic deformity; mean transmitral gradient of 6 mmHg at a heart rate of 60 beats per minute, moderate to severe mitral regurgitation(MR); estimated right ventricular systolic pressure of 45 mmHg.

Brain natriuretic peptide: 334 pg/mL (upper reference limit 100 pg/mL).

Discussion

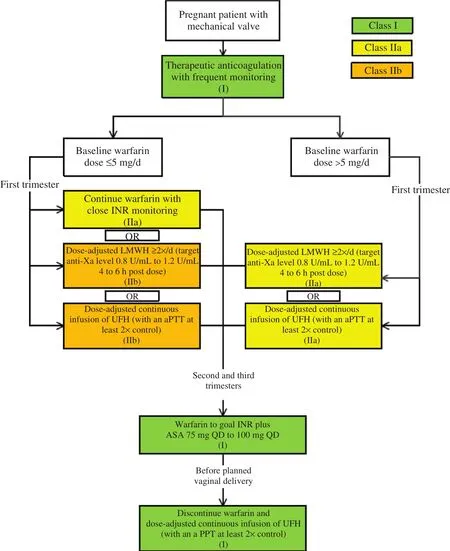

The patient is an otherwise healthy 35-year-old woman presenting with decreased exercise capacity.Her examination con firms the absence of overt congestive heart failure although her murmur is highly suggestive of signi ficant MR. Her transthoracic echocardiogram shows a dilated left ventricle both by LVESD and by LVEDV (110 mL/m2, the normal range for a woman her age is approximately 30–80 mL/m2) [ 1] with an LVEF of 60%. In the setting of compensated signi ficant MR, systolic function should be hyper dynamic (ejection fraction > 60%)as the ventricle can eject blood into the lowerimpedance left atrium. As a result, left ventricular(LV) function is inappropriately termed “ normal.”The mitral valve appears rheumatic ( Figure 1A,B), with a mean transmitral gradient of 6 mmHg,which may re flect some degree of mitral stenosis,although increased transmitral flow from MR is likely the dominant contributor. There is also moderate pulmonary hypertension, re flective of secondary effects of the MR on the pulmonary vascular system. MR severity in this case was interpreted as moderate to severe, highlighting the challenge of semiquantitative transthoracic echocardiographic assessment. Use of an integrative approach is necessary, combining both qualitative and quantitative assessment, along with a careful search for secondary associated findings ( Figure 2C, D). In addition to the inappropriately “ normal” LVEF, LV dilation,and pulmonary hypertension, the presence of left atrial enlargement (40 mL/m2, normal is < 34 mL/m2) [ 1] is also suggestive of chronic, severe MR.Finally, laboratory testing reveals an elevated brain natriuretic peptide level, which is associated with adverse events in patients with severe MR [ 4].Taken together, her clinical presentation, physical examination findings, transthoracic echocardiogram, and laboratory testing results are all consistent with severe symptomatic rheumatic MR.

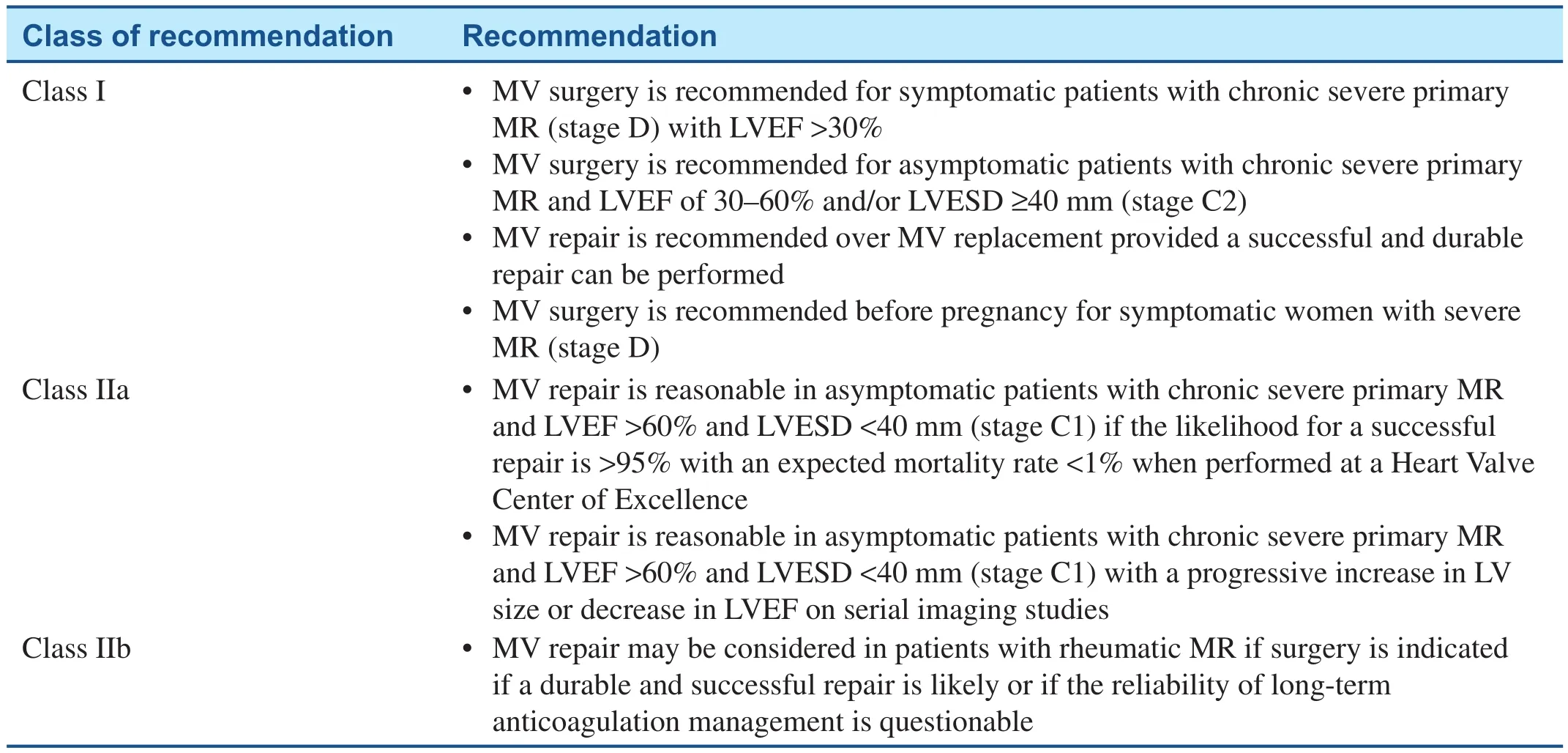

Patients with severe MR may remain asymptomatic for many years because of ventricular remodeling. In patients with severe degenerative MR (not rheumatic as in the patient presented here), the 8-year survival rate is more than 90%[ 5]. Among asymptomatic patients, those who develop a reduction in LV function or progressive LV dilation have worse outcomes ( Table 1)[ 6, 7]. Not surprisingly, it has also been demonstrated that outcomes are worse in patients who are symptomatic, regardless of LV function[ 6, 7]. As such, the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association valvular heart disease guidelines recommend mitral valve surgery in patients with severe primary MR who are symptomatic and in asymptomatic patients with LVEF of 30– 60% and LVESD of 40 mm or greater [ 6]. In those asymptomatic patients whose LVEF remains greater than 60%and whose LVESD remains less than 40 mm but who have developed a serial decrease in LVEF or increase in LVESD, surgery is also recommended[ 6]. While atrial fibrillation and pulmonary hypertension have been identi fied as potential triggers for surgical intervention in nonrheumatic severe primary MR, it has not been shown that these are independent prognostic markers in patients with rheumatic mitral valve disease [ 3].

Management of valvular heart disease in the patient considering pregnancy poses additional considerations. Pregnancy is associated with signi ficant hemodynamic changes [ 8]. As opposed to obstructive lesions, regurgitant valve lesions not associated with symptoms or LV systolic dysfunction are reasonably well tolerated up until delivery[ 9]. During labor, delivery, and the early postpartum period however, such patients can develop congestive heart failure and tachyarrhythmias because of the increase in venous return (autotransfusion)and systemic vascular resistance (from loss of the low-pressure uteroplacental circulation) [ 10]. A high threshold for valve intervention (transcatheter or surgical) during pregnancy is usually recommended, as procedural risks to the mother and baby can be substantial. Nevertheless, preexisting and/or pregnancy-related heart failure symptoms are associated with worse adverse maternal and fetal outcomes [ 11]. In the symptomatic patient with signi ficant MR considering pregnancy, proceeding with mitral valve surgery before pregnancy is recommended [ 3, 12].

Figure 1 Echocardiographic Imaging of a Rheumatic Mitral Valve.

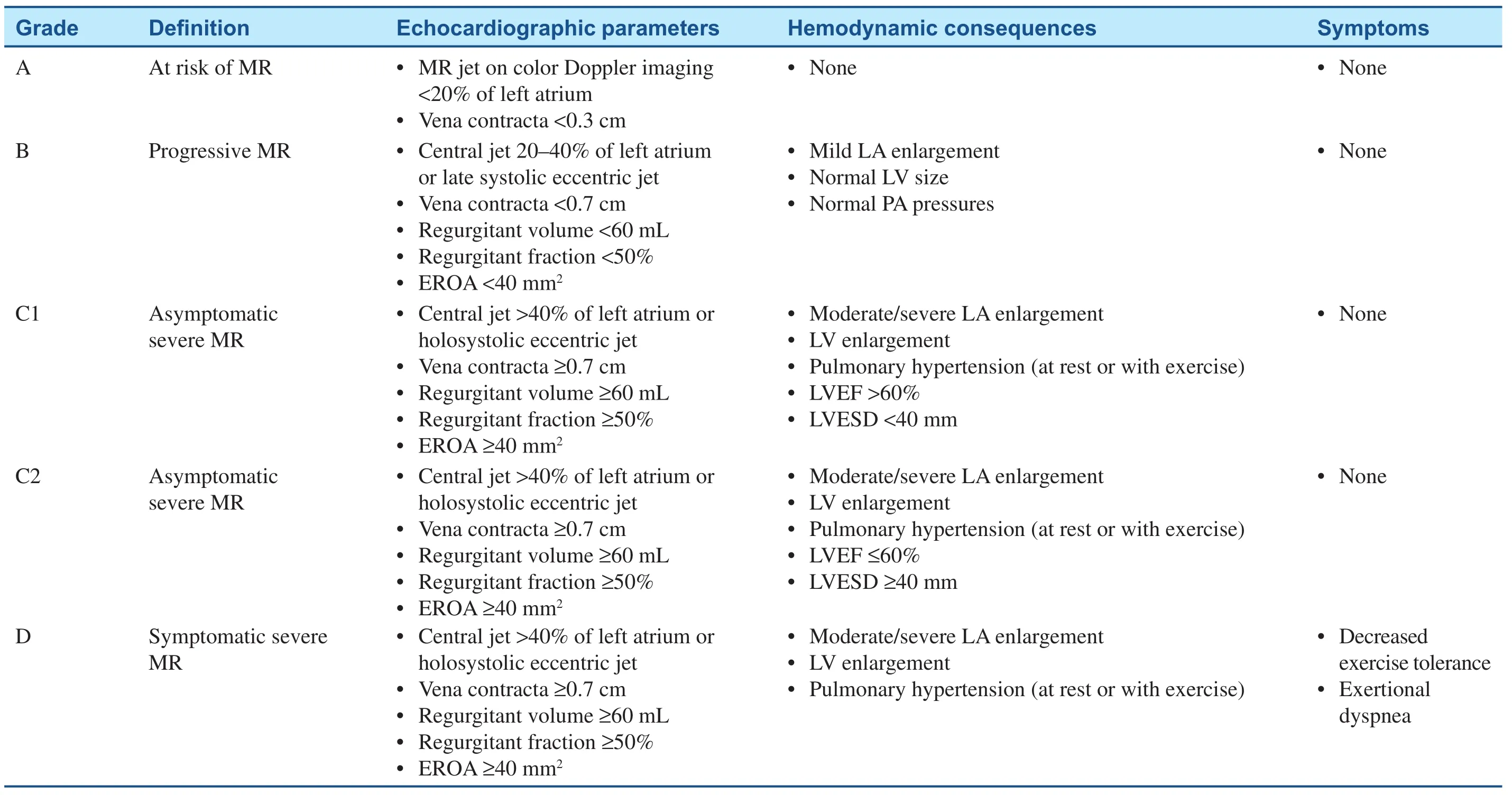

Figure 2 Anticoagulation Management Strategy for Pregnant Patients with Mechanical Heart Valves.

Once the decision has been made to proceed with surgery, what type of surgery is most appropriate?It is well established that the surgical risk of mitral valve replacement (MVR) for primary MR is higher than that associated with mitral valve repair and that outcomes are improved when surgery is performed at high-volume centers. In rheumatic mitral disease speci fically, recent data suggest that successful repair is possible in more than 80% of cases of severe MR and should be attempted if possible [ 13].In patients for whom repair is not possible, MVR is recommended with either a mechanical or a biological prosthesis. The advantage of a mechanical mitral prosthesis relates to its longer-term durability compared with a bioprosthesis, albeit with the need for anticoagulation with a vitamin K antagonist (VKA) with target international normalized ratio of 2.5– 3.5 along with low-dose aspirin [ 3,6]. Because of the high thrombotic risk with even short-term anticoagulation cessation, patients with mechanical MVR need to be bridged for noncardiac procedures [ 6]. Bioprosthetic valve durability has improved, with an average time to reoperation of approximately 12 years [ 14, 15]. Younger patients, however, are predisposed to accelerated valve degeneration [ 14]. After placement of a bioprosthetic mitral valve, patients are treated with a VKA for at least 3 months and then low-doseaspirin inde finitely, unless atrial fibrillation is present [ 6]. Patients undergoing mitral valve repair are treated similarly to those with bioprosthetic valves although their early thromboembolic risk is lower[ 16].

Table 1Stages of Primary Mitral Regurgitation (MR).

Table 2 Indications for Surgical Intervention for the Pregnant Patient with Severe Rheumatic Mitral Regurgitation (MR).

While a mechanical valve would be typically recommended in an otherwise healthy 35-year-old woman [ 6], her desire to become pregnant raises special considerations. Patients with mechanical heart valves who become pregnant are at high risk of thromboembolic complications likely due to the hypercoagulable state of pregnancy combined with the necessary alterations in anticoagulation management during this period [ 17]. Valve thrombosis is the most concerning complication, and carries a 20% risk of death [ 18]. While VKAs cross the placenta and are associated with adverse fetal outcomes (including miscarriage, stillbirth, and embryopathy), this effect is seen primarily at doses greater than 5 mg and is highest in the first trimester [ 19]. Low molecular weight heparin can be used with careful monitoring of anti-Xa levels, although there is some evidence to suggest that VKAs are more effective in preventing maternal mechanical valve thrombosis [ 19, 20]. Although often omitted,low-dose aspirin should be used in the second and third trimesters [ 18, 21]. Balancing these competing risks, the 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines put forth anticoagulation recommendations to best treat these complicated patients ( Table 2) [ 3]. While these recommendations can help treat patients with mechanical heart valves safely through pregnancy,there remains a high risk of complications that warrant consideration of bioprosthetic MVR if mitral valve repair cannot be performed. The advantage of bioprosthetic MVR in this setting is the ability to avoid VKA therapy, while the main disadvantage is the need for repeated intervention in the future.At the current time, repeated intervention would involve a reoperative surgical MVR, although percutaneous (mitral valve-in-valve) procedures can be considered in patients who are not surgical candidates [ 22]. Additional transcatheter MVRs are currently under investigation. There is no single correct option in this challenging patient population should a mitral valve repair not be feasible,and the choice of prosthesis should be the result of a shared decision making process involving the patient and her providers.

To return to the patient, she is a 35-year-old woman with severe rheumatic MR without signi ficant stenosis, LV dilation, and an inappropriately “ normal” LVEF presenting with progressive decline in exercise tolerance. Assuming that her history has been obtained carefully to exclude other causes of decreased exercise tolerance, it is reasonable to conclude that she is symptomatic from her severe MR. On the basis of the adverse pregnancy-related outcomes, as well as longerterm cardiovascular outcomes, surgical intervention is recommended. She should be evaluated by an experienced mitral valve surgeon, and a mitral valve repair should be performed if possible. If repair is not possible, replacement with either a bioprosthetic or a mechanical mitral valve should be considered, with advantages and disadvantages weighed carefully. There is no single correct answer for all patients, and a shared decision making process is necessary to reach the optimal solution for each individual patient. Regardless of the surgical intervention selected, she will need to continue with antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of recurrent rheumatic carditis until at least age 40 years (and potentially longer depending on her residual exposure to group A streptococcus), as well as before dental procedures for the prevention of infective endocarditis [ 23]. While the decision to proceed with surgery can seem straightforward when presented in a clinical vignette such as this,it is often more complicated in “ real life.” The symptoms are not always clear, echocardiographic assessment can be technically challenging, and the ability to predict reparability can be limited. While the data and guidelines serve an important role in helping craft recommendations for patients, the final treatment plan ultimately requires a multidisciplinary shared approach between the patient,cardiologist, cardiac surgeon, and maternal-fetal medicine specialist.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no Conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V,A filalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L,et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quanti fication by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;16(3):233– 70.

2. Zoghbi WA, Adams D, Bonow RO, Enriquez-Sarano M,Foster E, Grayburn PA, et al.Recommendations for noninvasive evaluation of native valvular regurgitation: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography developed in collaboration with the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2017;30(4):303– 71.

3. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Ruiz CE, Carabello BA,Skubas NJ, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63(22):e57– 185.

4. Detaint D, Messika-Zeitoun D,Avierinos JF, Scott C, Chen H,Burnett JC, et al. B-type natriuretic peptide in organic mitral regurgitation: determinants and impact on outcome. Circulation 2005;111(18):2391– 7.

5. Rosenhek R, Rader F, Klaar U,Gabriel H, Krejc M, Kalbeck D, et al. Outcome of watchful waiting in asymptomatic severe mitral regurgitation. Circulation 2006;113(18):2238– 44.

6. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP 3rd,Fleisher LA, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70(2):252– 89.

7. Tribouilloy CM, Enriquez-Sarano M, Schaff HV, Orszulak TA, Bailey KR, Tajik AJ, et al. Impact of preoperative symptoms on survival after surgical correction of organic mitral regurgitation: rationale for optimizing surgical indications.Circulation 1999;99(3):400– 5.

8. Sanghavi M, Rutherford JD. Cardiovascular physiology of pregnancy. Circulation 2014;130(12):1003– 8.

9. Stout KK, Otto CM. Pregnancy in women with valvular heart disease.Heart 2007;93(5):552– 8.

10. Lesniak-Sobelga A, Tracz W,KostKiewicz M, Podolec P,Pasowicz M. Clinical and echocardiographic assessment of pregnant women with valvular heart diseases– maternal and fetal outcome.Int J Cardiol 2004;94(1):15– 23.

11. Rezk M, Elkilani O, Shaheen A,Gamal A, Badr H. Maternal hemodynamic changes and predictors of poor obstetric outcome in women with rheumatic heart disease: a fiveyear observational study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2017;27:1– 6.

12. European Society of Gynecology(ESG), Association for European Paediatric Cardiology (AEPC),German Society for Gender Medicine (DGesGM), Regitz-Zagrosek V, Blomstrom Lundqvist C, Borghi C, et al. ESC guidelines on the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy:the Task Force on the Management of Cardiovascular Diseases during Pregnancy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2011;32(24):3147– 97.

13. Remenyi B, ElGuindy A, Smith SC,Yacoub M, Holmes DR. Valvular aspects of rheumatic heart disease.Lancet 2016;387(10025):1335– 46.

14. Jamieson WR, Von Lipinski O,Miyagishima RT, Burr LH, Janusz MT, Ling H, et al. Performance of bioprostheses and mechanical prostheses assessed by composites of valve-related complications to 15 years after mitral valve replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005;129(6):1301– 8.

15. Ruel M, Chan V, B é dard P, Kulik A, Ressler L, Lam BK, et al. Very long-term survival implications of heart valve replacement with tissue versus mechanical prostheses in adults < 60 years of age. Circulation 2007;116(11 Suppl):I294– 300.

16. Russo A, Grigioni F, Avierinos JF,Freeman WK, Suri R, Michelena H,et al. Thromboembolic complications after surgical correction of mitral regurgitation incidence, predictors,and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51(12):1203– 11.

17. Alshawabkeh L, Economy KE,Valente AM. Anticoagulation during pregnancy: evolving strategies with a focus on mechanical valves. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68(16):1804– 13.

18. van Hagen IM, Roos-Hesselink JW, Ruys TP, Merz WM, Goland S, Gabriel H, et al. Pregnancy in women with a mechanical heart valve: data of the European Society of Cardiology Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease (ROPAC).Circulation 2015;132(2):132– 42.

19. Vitale N, De Feo M, De Santo LS,Pollice A, Tedesco N, Cotrufo M.Dose-dependent fetal complications of warfarin in pregnant women with mechanical heart valves. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33(6):1637– 41.

20. Steinberg ZL, Dominguez-Islas CP, Otto CM, Stout KK, Krieger EV. Maternal and fetal outcomes of anticoagulation in pregnant women with mechanical heart valves. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69(22):2681– 91.

21. Economy KE, Valente AM.Mechanical heart valves in pregnancy: a sticky business. Circulation 2015;132(2):79– 81.

22. Paradis JM, Del Trigo M, Puri R, Rod é s-Cabau J. Transcatheter valve-in-valve and valve-in-ring for treating aortic and mitral surgical prosthetic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66(18):2019– 37.

23. Gerber MA, Baltimore RS, Eaton CB, Gewitz M, Rowley AH,Shulman ST, et al. Prevention of rheumatic fever and diagnosis and treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis: a scienti fic statement from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, the Interdisciplinary Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology, and the Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation 2009;119(11):1541– 51.

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications2018年1期

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications2018年1期

- Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications的其它文章

- Mitral Stenosis: A Review

- Functional Tricuspid Regurgitation and Ring Annuloplasty Repair

- Misdiagnosed Aortic Intramural Hematoma and the Role of Intravascular Ultrasound Imaging in Detection of Acute Aortic Syndrome: A Case Report

- An Asymptomatic Patient with Severe Mitral Regurgitation

- Clinical Evaluation of a Patient with Asymptomatic Severe Aortic Stenosis

- Low-Gradient, Low Ejection Fraction SevereAortic Stenosis: Still a Management Conundrum