阻断CD40-CD40L信号通路对小鼠肺移植术后闭塞性细支气管炎的影响

陈荣卷 陈其瑞 许江南 丁跃中*

(1.首都医科大学基础医学院免疫学系,北京 100069;2.首都医科大学附属北京朝阳医院胸外科,北京 100020)

肺移植是许多肺部终末期疾病患者的最终治疗方案,但患者术后存活率普遍低于其他实质性脏器移植手术[1]。限制肺移植长期生存的主要原因是术后闭塞性细支气管炎(obliterative bronchiolitis,OB)的发生和持续进行的慢性排斥反应[2-3]。临床研究[4]显示白细胞介素-17A(interleukin-17A,IL-17A)在OB的发展和肺移植术后排斥反应发生过程中起到了重要的作用,并且在动物模型中,利用抗IL-17A抗体中和IL-17A后可以有效减轻肺组织损伤和延长移植肺存活时间[4]。移植术后,IL-17A还可通过上调促炎因子如C-X-C模式趋化因子配体1[chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1,CXCL1]或 C-X-C模式趋化因子配体2[chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 2, CXCL2]参与中性粒细胞向移植肺的募集效应[5]。Th17细胞是IL-17A的重要来源细胞,由初始T细胞接受外来抗原或抗原呈递细胞呈递的抗原肽段刺激后分化发育而来。CD40-CD40L信号通路是激活T细胞的重要共刺激信号之一,CD40和CD40L的相互作用能够刺激抗原提呈细胞,增强其他共刺激信号如B7的表达以及增加促进T细胞分化的细胞因子的合成[6]。抗CD40L抗体能够有效阻断CD40-CD40L信号通路,抑制初始T细胞向效应T细胞的活化过程,从而在器官移植中延缓移植排斥的进展,减轻移植排斥反应和提高移植耐受性[7-9]。虽然在小鼠肺移植模型中,抗CD40L抗体的应用减轻了小鼠移植肺的病理损伤[10],但与传统免疫抑制剂治疗效果差异以及是否通过保护小气道和抑制炎性因子的表达从而延缓OB的发生和进展尚不明确。因此,本研究在小鼠原位左肺移植模型的基础上,研究注射抗CD40L抗体(MR1)后OB的进展、小气道损伤和IL-17A mRNA表达水平的变化,并和注射传统免疫抑制剂实验组进行比较,进一步探索肺移植排斥及OB的发生机制。

1 材料与方法

1.1 材料

1.1.1 动物及分组

无特定病原体级别(SPF级)雄性C57BL/6小鼠40只、SPF级雄性Balb/c小鼠30只,体质量24~28 g,均购买于北京维通利华技术有限公司,实验动物许可证号:SCXK(京)2016-0006。小鼠饲养于首都医科大学实验动物中心,实验单位使用许可证号:SYXK(京)2015-0012。本实验通过伦理审查(伦理编号:AEEI-2016-082)。将供受体按体质量采用抽签法随机配对分为4组(每组10只),分别为假手术对照组C57BL/6;同种异型0.9%(质量分数)氯化钠注射液(normal saline, NS)干预组Balb/c→C57BL/6; 同种异型环孢素/甲泼尼龙(cyclosporine/methylprednisolone, C/M)干预组Balb/c→C57BL/6;同种异型抗CD40L抗体(MR1)干预组Balb/c→C57BL/6。

1.1.2 主要试剂和仪器

试剂:环孢素/甲泼尼龙(Selleck公司,美国);抗CD40L抗体 (Bio X Cell公司,美国);抗髓过氧化物酶(Abcam公司,美国);TRIzol试剂(Invitrogen公司,美国);SYBR Green试剂盒(Qiagen公司,德国);反转录试剂盒(NEB公司,德国)。仪器:光学显微镜(Leica DM6000 B,德国);解剖显微镜(Olympus公司,美国);Roter-Gene Q PCR仪(Qiagen 公司,德国)。

1.2 方法

1.2.1 小鼠原位左肺移植模型的构建

麻醉:使用2%(质量分数)戊巴比妥钠按60 mg/kg剂量腹腔注射供体Balb/c小鼠。1)供体肺制取:将小鼠备皮消毒,连接呼吸机后,打开小鼠腹腔,将0.1 mL(100U/mL)肝素注入下腔静脉。打开小鼠胸腔,剪开心耳和上腔静脉,以预冷的肺泡灌洗液灌洗供体左肺。左肺取出后,暴露肺门结构,进行套管肺门的置入。动静脉气管套管置入后用0.9%(质量分数)氯化钠注射液湿润的无菌纱布覆盖,低温保存;2)受体操作:小鼠麻醉后备皮消毒,连接呼吸机,右侧卧位。打开受体小鼠胸腔,暴露肺门结构。以10-0尼龙线阻断动静脉血流,将供体肺动静脉气管套管经受体动静脉气管切口插入,以尼龙线扎紧。松开阻断血流的细线,使血流恢复。关闭胸腔和皮肤,皮肤切口处消毒处理,皮下注射抗生素。在呼吸机下观察小鼠,直至自主呼吸恢复即可撤除呼吸机。

1.2.2 给药及取材

假手术对照组、同种异型NS组与给药组腹腔注射同体积的0.9%(质量分数)氯化钠注射液;同种异型C/M组腹腔注射环孢素/甲泼尼龙,混合液环孢素剂量为10 mg·kg-1·d-1,甲泼尼龙剂量为1.6 mg·kg-1·d-1;同种异型MR1组注射同等剂量抗CD40L(克隆号:MR-1)抗体,25 mg·kg-1·d-1。各组给药10次,分别于术前1 d、术前当天和术后每24 h给药一次。术后10 d取小鼠移植左肺,进行指标检测。

1.2.3 移植左肺组织中IL-17A mRNA表达水平检测

肺移植术后10d,麻醉各组小鼠,获取小鼠移植左肺。使用Trizol提取移植物中的总RNA,反转录为cDNA。使用SYBR Green法实时荧光定量PCR检测IL-17A mRNA表达水平。实时荧光定量PCR循环设置条件为:预变性95 ℃ 2 min;变性95 ℃ 5 s;退火温度60 ℃ 10 s;延伸温度72 ℃ 30 s,共45个循环。引物序列详见表1。

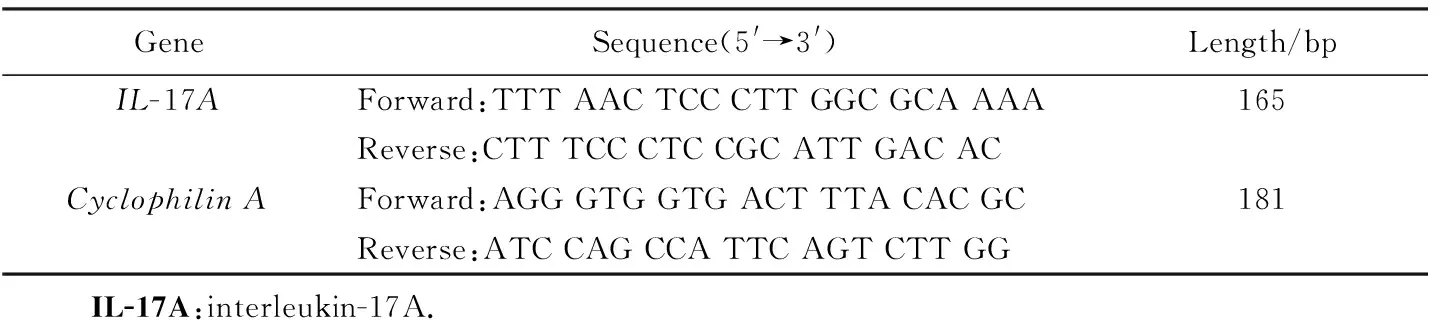

表1 RT-PCR引物序列Tab.1 Sequences of primers for RT-PCR

1.2.4 移植肺组织病理学检测

肺移植术后10d,麻醉各组小鼠,获取小鼠移植左肺。使用4%(质量分数)多聚甲醛固定肺组织,并将组织进行苏木精-伊红(hematoxylin-eosin, HE)染色、Masson染色以及利用抗髓过氧化物酶进行中性粒细胞组织化学染色。使用光学显微镜(Leica DM 6000B)观察染色后组织学病理改变,并进行病理评分和中性粒细胞浸润数量的统计。移植排斥病理评分等级为:0分=没有明显的炎性细胞浸润;1分=炎性细胞浸润支气管旁和血管周围;2分=炎性细胞浸润肺间质;3分=炎性细胞浸润肺泡;4分=炎性细胞浸润支气管腔内。纤维化病理评分参照早期Hübner等[11]的评分方式进行。中性粒细胞浸润数目统计方式为:统计人员在2个不同时间段进行评分,每次统计10个视野。每个视野统计采用显微镜放大400倍下的圆形视野中的特异性染色的中性粒细胞个数。

1.3 统计学方法

2 结果

2.1 模型构建结果

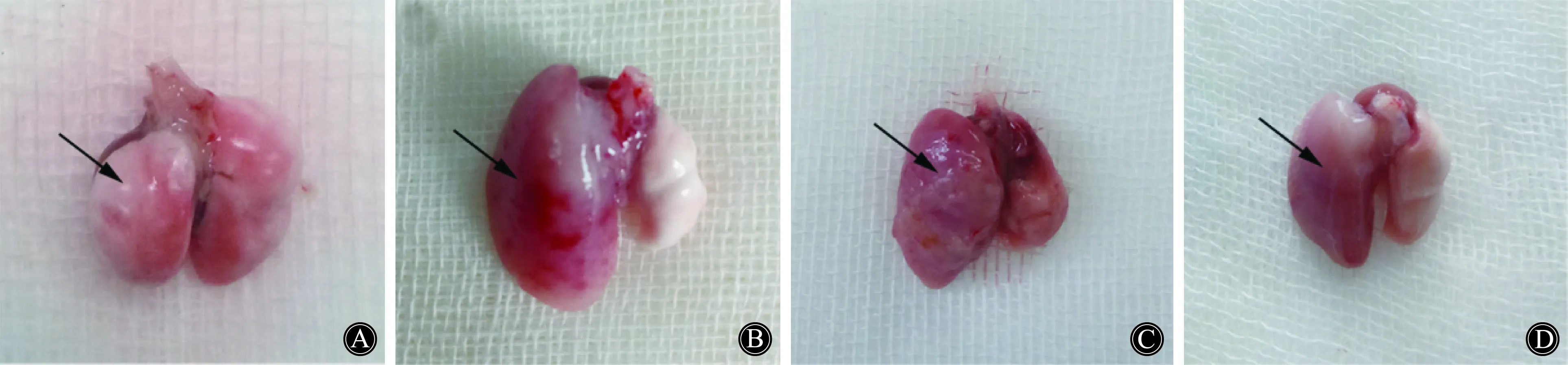

经过前期小鼠移植模型构建的学习,实验阶段小鼠肺移植成功率在95%以上,小鼠术后呼吸通畅,进食和活动度良好,无明显术后感染发生。术后10 d,牺牲小鼠收取移植左肺,相比假手术对照组,同种异型NS小鼠移植物明显水肿和纤维化外观,经传统免疫抑制剂治疗后小鼠左肺外观上有所改善,而抗CD40L抗体治疗组小鼠移植左肺改善较为明显(图1)。

图1 移植术后第10天移植物大体图Fig.1 Representative images of graft lungs harvested from grafts at 10th day

2.2 病理学分析

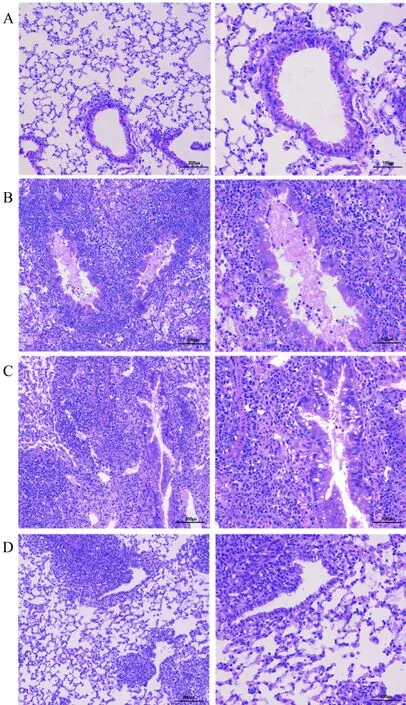

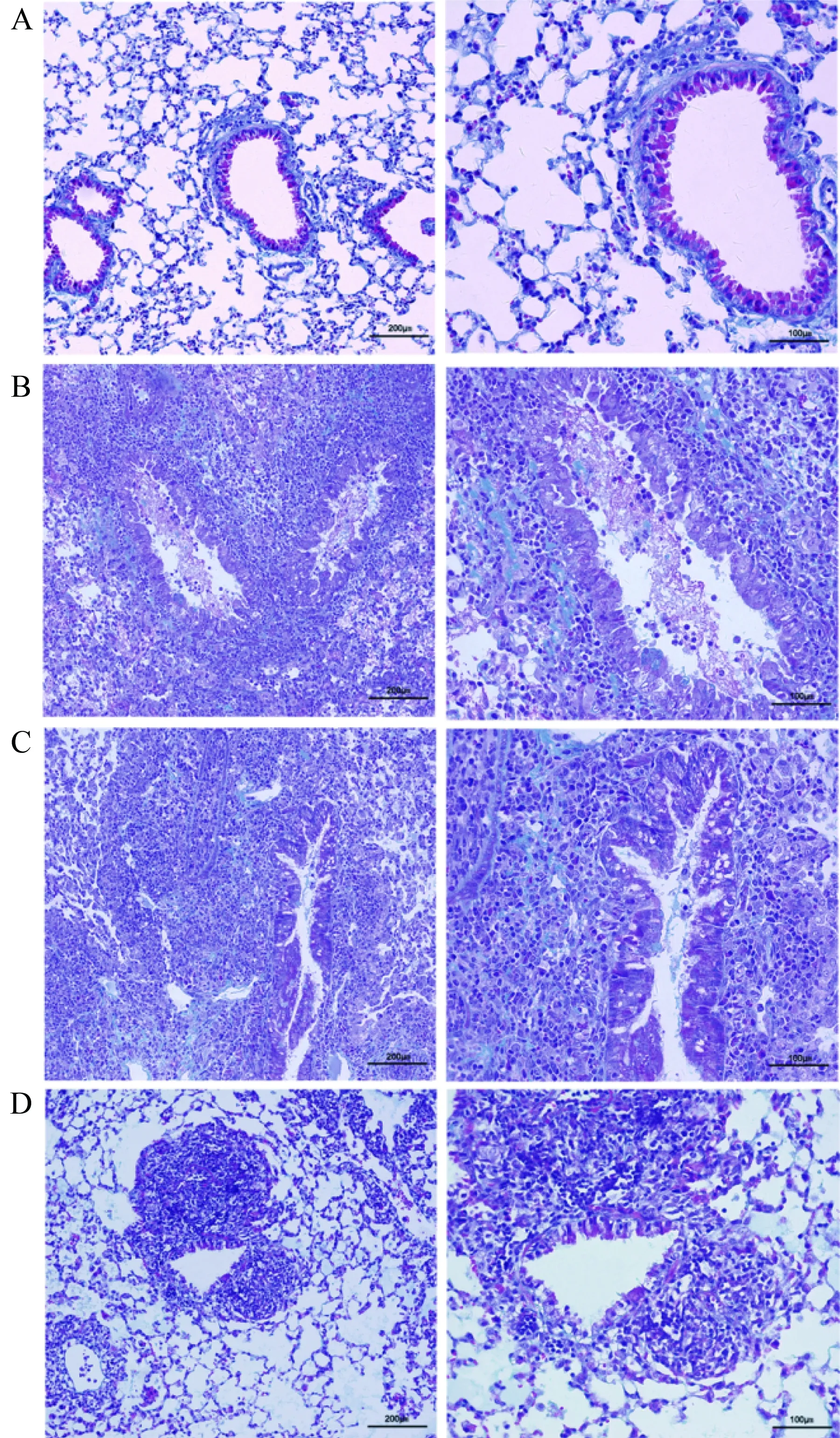

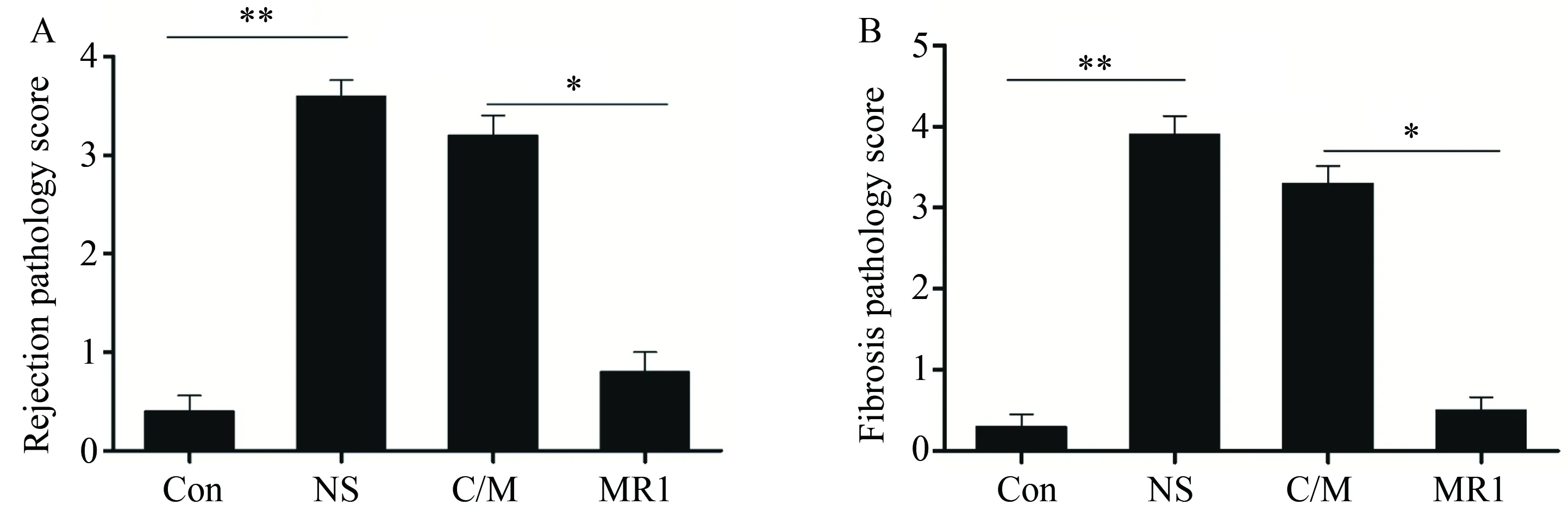

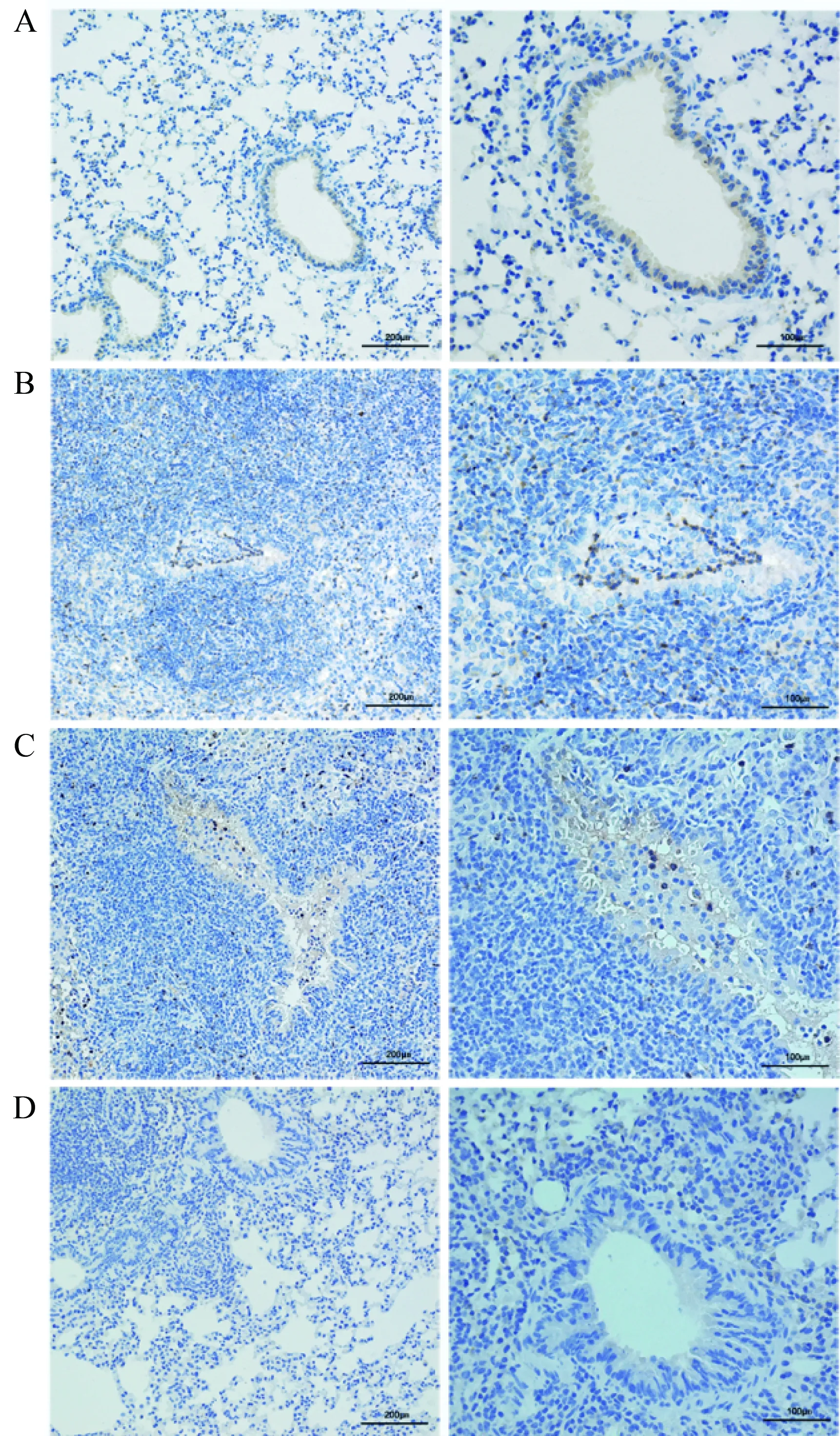

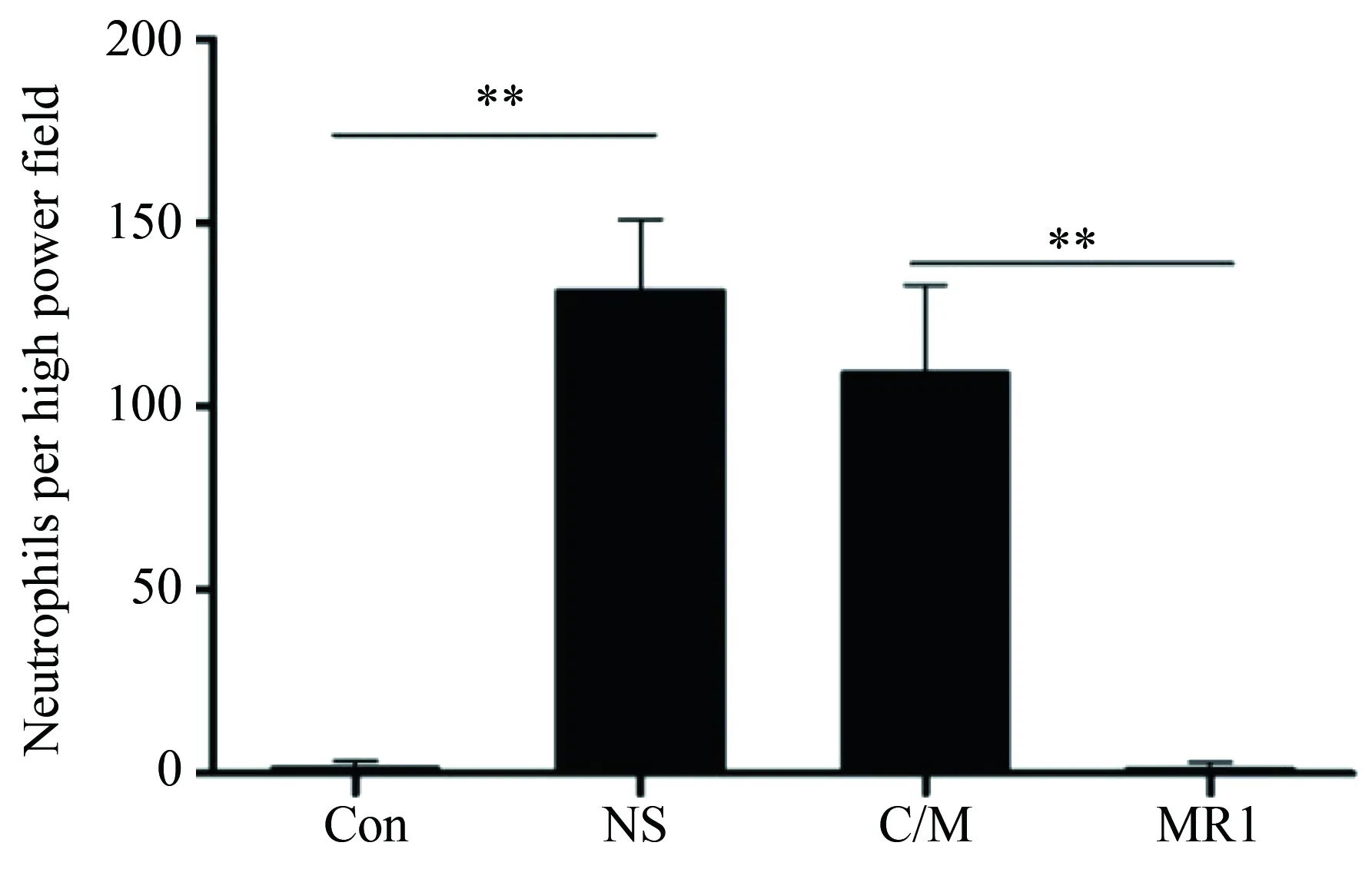

小鼠原位左肺移植术后10 d,相比于假手术组小鼠,在同种异型NS组小鼠病理学结果中可以观察到典型且较重的炎性细胞浸润和纤维化、OB现象以及小气道损伤(P<0.01)。传统免疫抑制剂环孢素/甲泼尼龙治疗组病理结果与NS组比较,差异无统计学意义,病理评分差异无统计学意义。与传统免疫抑制剂组比较,抗CD40L抗体治疗组移植物中炎性细胞浸润和纤维化以及OB都得到了明显的改善,小气道损伤减轻(P<0.05)(图2、3、4)。假手术组中未见明显中性粒细胞浸润性染色,而同种异型NS组病理结果中可以观察到明显中性粒细胞浸润(P<0.01)。与同种异型NS组相比,传统免疫抑制剂治疗后中性粒细胞浸润有所减少,但差异无统计学意义,而抗CD40L抗体相比于传统免疫抑制剂环孢素/甲泼尼龙效果显著(P<0.01)(图5、6)。

图2 移植术后第10天移植物的HE染色Fig.2 HE staining of graft at 10th day after transplantation

图3 移植术后第10天移植物的Masson染色Fig.3 Masson staining of graft at 10th day after transplantation

图4 移植术后第10天移植物相关病理统计结果Fig.4 Pathology scores of lung grafts at 10th day

图5 移植术后第10天移植物的中性粒细胞特异性染色Fig.5 Neutrophil staining with antimyeloperoxidase of graft at 10th day after transplantation

2.3 炎性细胞因子表达水平

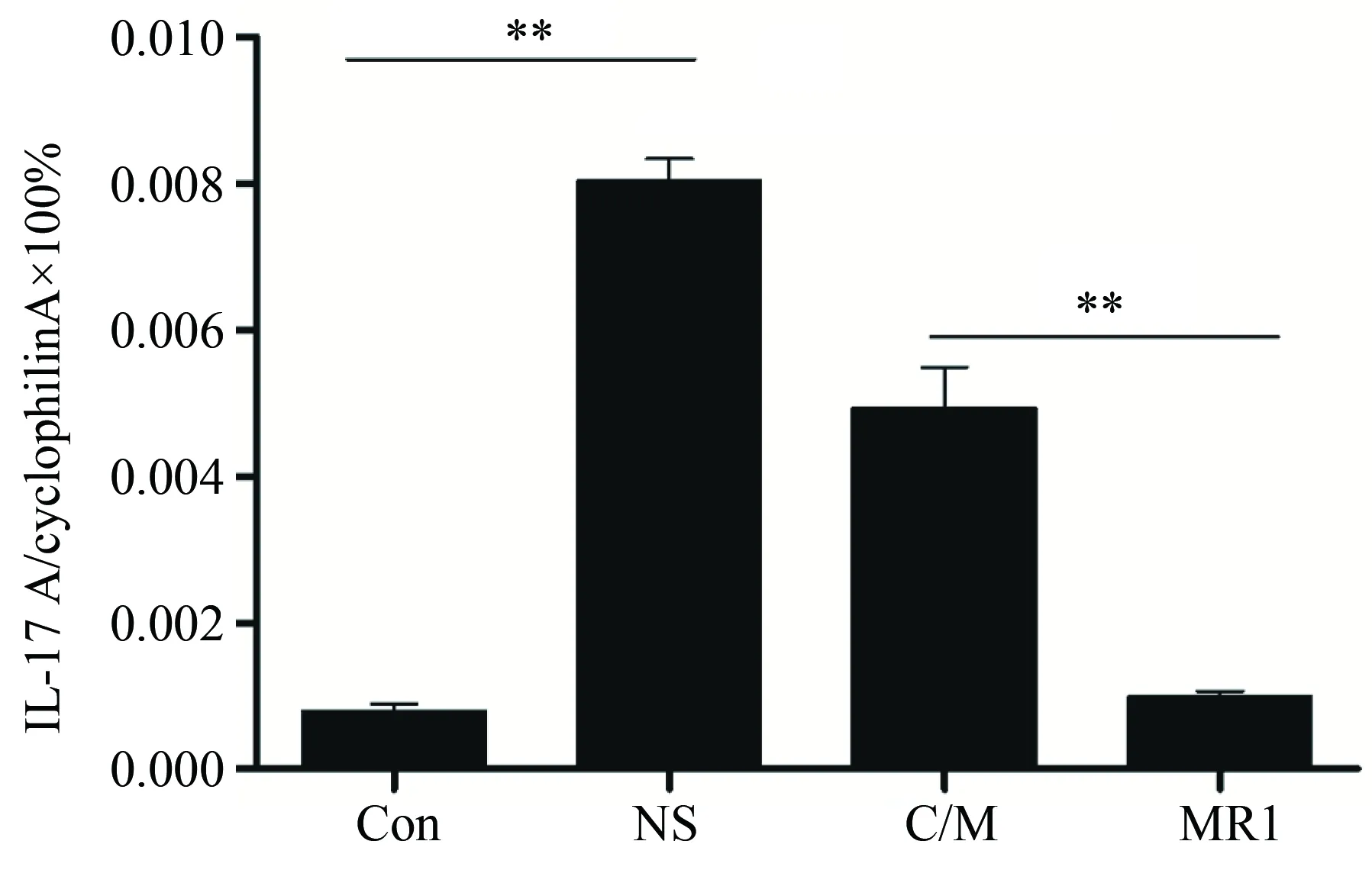

术后10 d,小鼠抑制左肺组织中IL-17A mRNA表达水平检测结果显示,同种异型NS组较假手术对照组的IL-17A mRNA表达水平显著增高(P<0.01);而注射传统免疫抑制剂后,IL-17A mRNA表达水平与NS组相比有所降低,但差异无统计学意义;抗CD40L抗体治疗组移植物中IL-17A mRNA表达水平则低于传统免疫抑制剂环孢素/甲泼尼龙(P<0.01)。实验结果提示原位左肺移植模型中注射了抗CD40L抗体后可以有效降低移植肺中IL-17A的表达,且效果优于传统免疫抑制剂环孢素/甲泼尼龙联合注射(图7)。

图6 移植术后第10天移植物中性粒细胞统计结果Fig.6 Total number of neutrophils per high-power field of lung grafts at 10th day

图7 移植术后第10天移植物中IL-17A表达Fig.7 The expression levels of IL-17A at 10th day after transplantation

3 讨论

移植术后的慢性排斥和OB的发生是长期以来影响临床患者肺移植术后长期生存的最主要因素[2]。早期肺移植相关研究受限于模型的构建,无法顺利开展,随着小鼠原位左肺移植模型的建立和不断的完善,逐渐构建起了完整的小鼠移植模型体系,且能够较好的模拟临床肺移植过程,再现移植排斥和OB的发生[12-14]。本研究则采用小鼠原位左肺移植模型进行相关实验。

研究[15]表明,T细胞和其相关细胞因子在移植排斥中发挥了重要的作用,但具体的机制仍不明确。初始T细胞识别外来抗原或抗原提呈细胞提呈的抗原后在共刺激分子如B7和CD28以及CD40L和CD40协同作用下,不断分化发育成成熟T细胞,其中包括了IL-17A的重要来源细胞Th17细胞。CD40L多表达于激活的T细胞表面,而CD40多见于B细胞、巨噬细胞和树突状细胞等。CD40和CD40L的相互作用能够刺激抗原提呈细胞,增强共刺激信号B7,增加促进T细胞增生分化的细胞因子的合成,包括了IL-6、IL-8、IL-12、干扰素-γ(interferon-γ,IFN-γ)等细胞因子,从早期实验移植模型中观察到阻断该信号通路能够建立移植受体对移植物长期的免疫耐受性后,便受到了广泛的关注[16-19]。 抗CD40L抗体能够竞争性结合该信号通路, 导致初始T细胞无法被正常激活,从而减轻移植物中Th17等炎性细胞的浸润情况,因此被应用于多个移植模型研究中,且能够有效减轻移植物排斥反应,延长生存时间[20-22]。本研究结果表明,与注射0.9%(质量分数)氯化钠注射液和传统免疫抑制剂环孢素/甲泼尼龙联合治疗组相比,抗CD40L抗体治疗组受体小鼠移植左肺中移植排斥反应得到了较好的缓解;炎性细胞浸润,纤维组织增生,小气道损伤以及OB的发生情况都有明显的减轻。

IL-17A是IL-17家族中的一员,临床和动物研究[23-25]显示,IL-17A密切参与了肺移植术后的排斥反应及OB发生过程。一项研究[4]显示,通过向受体小鼠注射IL-17A中和抗体,能够有效减轻排斥反应,延缓OB的发展,说明IL-17A在肺移植中发挥了重要的作用。有文献[26]报道V型胶原参与了OB的病理发展过程以及肺部纤维化的病理过程,且和IL-17A表达水平关系密切。中和了IL-17A后V型胶原含量显著降低,且在一定程度上减轻移植物的病理损伤[27]。临床研究[28-30]显示,移植排斥的发生伴随着中性粒细胞浸润和纤维化组织增生都与IL-17A大量表达有着密切关联,IL-17A可以通过上调气道上皮中促炎因子如CXCL1和CXCL2来募集中性粒细胞转移向移植肺。纤维化的发生有着复杂且众多类型细胞参与,其虽与IL-17A的表达水平相关,但具体的机制仍有待研究[31]。本研究结果显示,注射了抗CD40L后,IL-17A表达水平显著降低,与注射0.9%(质量分数)氯化钠注射液组相比,抗CD40L抗体治疗组抑制IL-17A表达效果强于环孢素/甲泼尼龙,且减轻了中性粒细胞的浸润程度,这种缓解效应未在环孢素/甲泼尼龙干预组中发现。综上所述,抗CD40L抗体可以有效降低移植肺中IL-17A表达水平,从而保护小气道,减轻中性粒细胞的浸润和纤维组织增生,延缓肺移植术后闭塞性细支气管炎的发生,单用效果优于环孢素/甲泼尼龙联合治疗。然而其具体的作用机制,仍有待进一步深入研究。

致谢:本课题的顺利完成还需感谢首都医科大学免疫学系白力同学在实验过程中给予的启发和文稿修改上给出的合理建议。

[1] Wilkes D S, Egan T M, Reynolds H Y. Lung transplantation: opportunities for research and clinical advancement[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2005,172(8):944-955.

[2] Christie J D, Edwards L B, Kucheryavaya A Y, et al. The registry of the international society for heart and lung transplantation: twenty-seventh official adult lung and heart-lung transplant report-2010[J]. J Heart Lung Transplant, 2010,29(10):1104-1118.

[3] Belperio J A, Weigt S S, Fishbein M C, et al. Chronic lung allograft rejection:mechanisms and therapy[J]. Proc Am Thrac Soc, 2009, 6(1):108-121.

[4] Chen Q R, Wang L F, Xia S S, et al. Role of interleukin-17A in early graft rejection after orthotopic lung transplantation in mice[J]. J Thorac Dis, 2016, 8(6):1069-1079.

[5] Shilling R A, Wilkes D S. Role of Th17 cells and IL-17 in lung transplant rejection[J]. Semin Inmmunopathol,2011, 33(2): 129-134.

[6] Mcdyer J F, Goletz T J, Thomas E, et al. CD40 ligand/CD40 stimulation regulates the production of IFN-gamma from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in an IL-12-and/or CD28-dependent manner[J]. J Immunol, 1998, 160(4):1701-1707.

[7] Ensminger S M, Witzke O, Spriewald B M, et al. CD8+T cells contribute to the development of transplant arteriosclerosis despite CD154 blockade[J]. Transplantation, 2000, 69(12):2609-2612.

[8] Guo Z, Meng L, Kim O, et al. CD8 T cell-mediated rejection of intestinal allografts is resistant to inhibition of the CD40/CD154 costimulatory pathway[J]. Transplantation, 2001, 71(9):1351-1354.

[9] Jones N D, Van M A, Hara M, et al. CD40-CD40 ligand-independent activation of CD8+T cells can trigger allograft rejection[J]. J Immunol, 2000, 165(2):1111-1118.

[10] Dodd-o J M, Lendermon E A, Miller H L, et al. CD154 blockade abrogates allospecific responses and enhances CD4+regulatory T cells in mouse orthotopic lung transplant[J]. Am J Transplant, 2011, 11(9):1815-1824.

[11] Hübner R H, Gitter W, El Mokhtari N E, et al. Standardized quantification of pulmonary fibrosis in histological samples[J]. Biotechniques, 2008, 44(4):507-511.

[12] Lin X, Li W, Lai J, et al. Five-year update on the mouse model of orthotopic lung transplantation: Scientific uses, tricks of the trade, and tips for success[J]. J Thorac Dis, 2012, 4(3):247-258.

[13] Jungraithmayr W, Weder W. The technique of orthotopic mouse lung transplantation as a movie-improved learning by visualization[J]. Am J Transplant, 2012, 12(6):1624-1626.

[14] Krupnick A S, Lin X, Li W, et al. Orthotopic mouse lung transplantation as experimental methodology to study transplant and tumor biology[J]. Nat Protoc, 2009, 4(1):86-93.

[15] Paantjens A W, Vande Graaf E A, Kwakkel-van Erp J M, et al. Lung transplantation affects expression of the chemokine receptor type 4 on specific T cell subsets[J]. Clin Exp Immunol, 2011, 166(1):103-109.

[16] Lunsford K E, Jayanshankar K, Eiring A M, et al. Alloreactive (CD4-independent)CD8+T cells jeopardize long-term survival of intrahepatic islet allografts[J]. Am J Transplant, 2008, 8(6):1113-1128.

[17] Trambley J, Bingaman A W, Lin A, et al. Asialo GM1+CD8+T cells play a critical role in costimulation blockade-resistant allograft rejection[J]. J Clin Invest, 1999, 104(12):1715-1722.

[18] Henn V, Steinbach S, Büchner K, et al. The inflammatory action of CD40 ligand (CD154) expressed on activated human platelets is temporally limited by coexpressed CD40[J]. Blood, 2001, 98(4):1047-1054.

[19] Quezada S A, Jarvinen L Z, Lind E F, et al. CD40/CD154 interactions at the interface of tolerance and immunity[J]. Annu Rev Immunol, 2004, 22(1):307-328.

[20] Bucher P, Gang M, Morel P, et al. Transplantation of discordant xenogeneic islets using repeated therapy with anti-CD154[J]. Transplantation, 2005, 79(11):1545-1552.

[21] Kalache S, Lakhani P, Heeger P S. Effects of preexisting autoimmunity on heart graft prolongation after donor-specific transfusion and anti-CD154[J]. Transplantation, 2014, 97(1):12-19.

[22] Zhang T, Pierson R N 3rd, Azimzadeh A M. Update on CD40 and CD154 blockade in transplant models[J]. Immunotherapy, 2015, 7(8):899-911.

[23] Yamada Y, Vandermeulen E, Heigl T, et al. The role of recipient derived interleukin-17A in a murine orthotopic lung transpl model of restrictive chronic lung allograft dysfunction[J]. Transpl Immunol, 2016, 39:10-17.

[24] Fan L, Benson H L, Vittal R, et al. Neutralizing IL-17 prevents obliterative bronchiolitis in murine orthotopic lung transplantation[J]. Am J Transplant, 2011, 11(5):911-922.

[25] Gupta P K, Wagner S R, Wu Q, et al. IL-17A blockade attenuates obliterative bronchiolitis and IFNγ cellular immune response in lung allografts[J]. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, 2017 56(6):708-715.

[26] Vanaudenaerde B M, De Vleeschauwer S I, Vos R, et al. The role of the IL23/IL17 axis in pronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after lung transplantation[J]. Am J Transplant, 2008, 8(9):1911-1920.

[27] Burlingham W J, Love R B, Jankowska-Gan E, et al. IL-17-dependent cellular immunity to collagen type V predisposes to obliterative bronchiolitis in human lung transplants[J]. J Clin Invest, 2007, 117(11):3498-3506.

[28] Zheng L, Walters E H, Ward C, et al. Airway neutrophilia in stable and bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome patients following lung transplantation[J]. Thorax, 2000, 55(1):53-59.

[29] Kawaguchi M, Onuchic L F, Li X D, et al. Identification of a novel cytokine, ML-1, and its expression in subjects with asthma[J]. J Immunol, 2001, 167(8):4430-4435.

[30] Bonville C A, Percopo C M, Dyer K D, et al. Interferon-gamma coordinates CCL3-mediated neutrophil recruitment in vivo[J]. BMC immunol, 2009, 10(1):14.

[31] Govan J R, Deretic V. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid pseudomonas aeruginosa and burkholderia cepacia[J]. Microbiol Rev, 1996, 60(3):539-574.