干旱半干旱区土壤微生物空间分布格局的成因

黄艺,黄木柯,柴立伟,赵嫣然

北京大学环境科学与工程学院,北京 100871

干旱是地球表面的主要特征之一(Pointing et al.,2012),干旱地区(Drylands)占据陆地表面41%以上的面积(Safriel et al.,2005)。干旱程度常用干旱指数AI(Aridity Index)来反映,其含义是年平均降水量与年平均蒸发量的比值(Safriel et al.,2005),其中干旱指数在0.05~0.20之间的地区为干旱区(Arid regions),0.20~0.50之间的地区为半干旱区(Semi-arid regions)。干旱半干旱区的总面积为3.83×107km2,是陆地生态系统的重要组成部分,聚集了超过38%的世界人口,是人类重要的居住和生活场所(Safriel et al.,2005;Reynolds et al.,2007)。然而,干旱半干旱区降水稀少且分布不均、蒸发强烈(Whitford,2002),土壤营养元素缺乏,水分及有机质含量低(Noy-Meir,1979;Saul-Tcherkas et al.,2009),对气候变化和人为活动干扰都极为敏感,容易退化为没有生产力的荒漠(Hagemann et al.,2015)。根据模型预测,随着气候变化的加剧,干旱区的面积还将逐渐扩大(Burke et al.,2006;Dai,2013;Fu et al.,2014)。如何在干旱半干旱环境下发展生产、提高生活水平,同时又不引起该地区的生态退化,成为环境生态领域的重要研究课题。其中,探索干旱条件下,提高土壤稳定性、维持可持续生产力和生物多样性的理论和方法,又是该研究的核心问题之一。

地表生物空间分布格局的研究(Lozupone et al.,2007;Ramette et al.,2007;Bell et al.,2009),是理解生态系统完整性和生物多样性形成及维持机制,保护生态系统稳定和生物多样性的基础(Ferrier et al.,2004;Stuart et al.,2004;Green et al.,2006)。在干旱半干旱环境下,土壤中的微生物群落不仅是土壤中碳、氮、磷等营养元素生物地球化学循环的主要驱动力(Green et al.,2004),还与成土过程及土壤的保水保肥能力有密切关系(Evans et al.,1999)。因此,研究干旱半干旱区土壤微生物空间分布格局及其影响因素,探索该区土壤微生物空间分布格局的形成机制,对保护该区生态系统,维持稳定的地上生态系统生产力等显得尤为重要。本文对近10年来国内外在干旱半干旱区进行土壤微生物群落空间分布的相关研究进行综述,并对未来的研究提出建议,以促进干旱半干旱土壤微生物的深入研究。

1 干旱半干旱区土壤微生物具有空间分布格局

生物的空间分布格局是指在空间的不同位置分布的生物群落不同,并且可能受一定因素的影响呈现某种特殊的分布规律。在微生物空间分布格局的研究中,常用微生物群落的生物量、物种组成、个体丰度或多样性在空间上的分异来描述微生物的空间分布格局。

对于微生物是否存在空间分布格局一直存在广泛的讨论及争议。传统观点认为微生物在全球呈随机分布,即“everything is everywhere”,微生物不存在空间分布格局(Becking,1934;De et al.,2006;O'Malley,2008)。但越来越多的研究证明,微生物在空间上具有一定的分布格局。在干旱半干旱区土壤微生物空间分布格局的研究中,尽管有部分研究指出在较小的局域(local)尺度上(<10 km),土壤细菌群落的丰富度、物种的多样性在空间分布上不存在显著差异(Saul-Tcherkas et al.,2011;Hortal et al.,2013;Steven et al.,2013),但综合考虑微生物生物量、物种组成等的空间分异,认为干旱半干旱区土壤微生物呈非随机分布,具有一定的空间分布格局(Fierer et al.,2005;Tsiknia et al.,2014;Maestre et al.,2015)。

此外,总结目前有关细菌、真菌及古菌优势菌群的分布研究可知,干旱半干旱区不同的微生物类群均存在空间分布格局(Maestre et al.,2015)。表1列出了近年来在干旱半干旱区土壤中发现的细菌群落的优势门。由表可知,干旱半干旱区土壤中细菌群落的优势门与其他陆地生态系统中常见的优势门类似(Janssen,2006;Fierer et al.,2012;Barnard et al.,2013),主要为放线菌门(Actinobacteria)、变形菌门(Proteobacteria)、酸杆菌门(Acidobacteria)和拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)。而且,全球尺度下,不同地区的干旱半干旱区的细菌群落的优势门不同,其相对丰度也不同。

相较于细菌,干旱半干旱区土壤真菌及古菌群落的研究十分有限。现有研究表明,土壤真菌群落的优势门主要为子囊菌门(Ascomycota)及担子菌门(Basidiomycota)(Maestre et al.,2015,Bastida et al.,2014;Martirosyan et al.,2016;Rao et al.,2016)。就古菌群落而言,一些研究认为古菌群落的优势门主要为泉古菌门(Crenarchaeota)(Fierer et al.,2012;Angel et al.,2013;Valverde et al.,2015),而Wang et al.(2015)在中国干旱半干旱区的研究发现泉古菌门中热变形菌纲(Thermoprotei)占据主要优势地位,此外,广古菌门(Euryarchaeota)中的嗜盐古菌纲(Halobacteria)也是干旱半干旱区古菌群落的优势纲。

2 干旱半干旱区土壤微生物空间分布格局的影响因素

在实际观察到的干旱半干旱区土壤微生物存在空间分布格局的基础上,大量研究关注了降水、植被及土壤理化性质等环境因素和地理距离与微生物的群落组成、生物量、多样性及个体丰度之间的关系,试图揭示影响干旱半干旱区土壤微生物分布的成因。现有的研究结果表明,环境因素及地理距离都会影响干旱半干旱区土壤微生物的分布格局,并且微生物类群不同,时空尺度不同,影响其空间分布格局的主要因素则随之不同。

2.1 环境因素显著影响干旱半干旱区土壤微生物的空间分布格局

2.1.1 气候因素的影响

水参与微生物新陈代谢的诸多反应,是微生物生存和生长必不可少的物质之一。因此,在干旱胁迫下,降水作为一种限制因子能显著影响土壤微生物的空间分布格局。诸多研究显示,干旱半干旱区,土壤微生物群落的总生物量(Huang et al.,2015,Zhao et al.,2016)、细菌(Cregger et al.,2012)、真菌(Maestre et al.,2015)及放线菌的生物量与年平均降水量呈显著正相关关系(Chen et al.,2015)。细菌群落及真菌群落的物种多样性也会随降水的增加而显著增加(Navarro-Gonzalez,2003;Maestre et al.,2015)。就细菌群落而言,环境越是干旱,降水对其多样性的影响越大(Wang et al.,2015)。Chen et al.(2015)及 Tripathi et al.(2017)的研究甚至认为,在这种水分受到限制的干旱半干旱环境下,降水是影响土壤细菌群落分布格局的最主要的决定性因素。

不同于细菌及真菌,古菌在年平均降水量较低,相对干旱的地区多样性反而更高(Chen et al.,2015)。可能的原因是古菌能生活于高温、高盐等各种极端环境下,在干旱这种极端环境下,古菌可能也占据了特殊的生态位,能适应干旱胁迫而正常生长。因此,加强干旱半干旱地区土壤中古菌群落空间分布格局的研究,对维持该地区生态系统的稳定性,及开发土壤微生物资源具有重要意义。

降水除了影响干旱半干旱区土壤微生物生物量、多样性的分布外,还会影响个体丰度的分布格局。年平均降水量较高,相对湿润的地区,细菌群落中酸杆菌门(Actinobacteria)(Wang et al.,2015;Maestre et al.,2015),浮霉菌门(Plancomycene)(Wang et al.,2015),及疣微菌门(Verrucomicrobia)(Maestre et al.,2015)的相对丰度显著高于较干旱的地区,而绿湾菌门(Chloroflexi)、放线菌门(Actinobacteria)、α-变形菌门(α-Proteobacteria)(Maestre et al.,2015;Wang et al.,2015;Taketani et al.,2017)、拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)、厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)及芽单胞菌门(gemmatimonadetes)(Niederberger et al.,2015)的相对丰度在干旱地区反而相对较高。

2.1.2 土壤理化性质的影响

土壤理化性质直接决定了土壤微生物生存的环境,进而影响土壤微生物群落(Wardle,2004;De Deyn et al.,2005)。在干旱半干旱区,土壤含水率(SWC)、pH、土壤电导率、有机质含量(SOM)、氮元素、磷元素(Pajares et al.,2016)、阴阳离子的含量(Li et al.,2012)等诸多因素都影响土壤微生物的空间分布格局,其中土壤含水率(SWC)、pH及土壤养分如有机质、氮素含量等对其影响较大。

水分是干旱半干旱环境下土壤微生物活动的重要限制因素,因此土壤微生物的生物量(Schlesinger et al.,1990;Fliesbach et al.,1994;Sarig et al.,1996;Bell et al.,2008)及多样性(Navarro-Gonzalez,2003;Zeglin et al.,2011;Bell et al.,2014;Armstrong et al.,2016)会随土壤含水率的增加而增加。Taniguchi et al.(2012)通过进一步的相关性分析指出,土壤含水率在0%~15%范围内时,干旱半干旱区土壤细菌、真菌群落的多样性与土壤含水率呈显著正相关关系。

很多研究强调pH是影响微生物群落分布的关键因素(Fierer et al.,2009;Jesus et al.,2009;Jones et al.,2009),在干旱半干旱环境中,土壤的pH与丛枝菌根真菌(Bainard et al.,2014)及古菌(Wang et al.,2015)的多样性均呈显著正相关,pH通过影响它们的多样性来改变其空间分布格局。就细菌群落而言,虽然土壤pH与土壤细菌群落多样性的相关性不显著(Wang et al.,2015),但是土壤pH可通过改变细菌群落的个体丰度进而改变干旱半干旱区细菌群落的空间分布(Fierer et al.,2006;Wang et al.,2015)。例如,Wang et al.(2015)研究指出,干旱半干旱环境下,细菌群落中绝大多数优势门的相对丰度与土壤pH呈负相关关系,但放线菌门(Actinobacteria)、厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)及绿湾菌门(Chloroflexi)的相对丰度却与土壤pH呈显著正相关关系。另外,诸多在国家、洲际水平等较大空间尺度下的研究指出,土壤pH是细菌空间分布格局的最重要的决定性的影响因素(Fierer et al.,2006;Lauber et al.,2009;Chu et al.,2010;Griffiths et al.,2011)。而目前干旱半干旱区的相关研究结果表明,pH也会影响细菌群落的空间分布格局,但不是最重要的决定性因素。分析其原因可能是在干旱半干旱区的相关研究中,调查的空间尺度不够大,pH值集中在6~10之间,变化较小,掩盖了pH值对细菌群落空间分布的影响。

干旱半干旱区土壤贫瘠,土壤养分是微生物活动的重要限制因素,对土壤微生物群落的分布格局具有重要影响(Chen et al.,2015;Zhao et al.,2016)。Hu et al.(2014)对中国干旱半干旱区的草地生态系统的研究发现,土壤微生物群落总生物量、细菌、真菌的生物量与土壤有机碳(SOC)含量呈显著正相关。土壤细菌群落的多样性与土壤总有机碳(TOC)及总氮(TN)呈显著正相关(Wang et al.,2015)。主要原因是土壤养分特别是有机质、氮素含量的提高有利于土壤微生物种群数量及微生物生物量的积累(Nishiyama et al.,2001;Ralte et al.,2005)。此外,土壤养分还会影响细菌群落中的个体丰度的分布格局,Bastida et al.(2016)的研究发现细菌群落中的放线菌门(Actinobacteria)及变形菌门(Proteobacteria),真菌群落中的担子菌门(Basidiomycota)的相对丰度均与土壤中溶解性有机碳(DOC)的含量呈显著正相关。然而,细菌群落中的酸杆菌门(Acidobacteria)、拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)、厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)、蓝细菌(Cyanobacteria)、芽单胞菌门(Gemmatimonadetes)、绿湾菌门(Chloroflexi)及疣微菌门(Verrucomicrobia),真菌群落中的子囊菌(Ascomycota)、球囊菌门(Glomeromycota)及壶菌门(Chytridiomycota)的相对丰度随土壤中溶解性有机碳(DOC)的含量的增加而减少。

2.1.3 植被的影响

地上植被的凋落物、根系等均会对地下的微生物群落产生影响(De Deyn et al.,2005)。在干旱半干旱环境下,地上植被对地下土壤微生物群落的空间分布格局的影响尤为明显。研究表明,干旱半干旱区灌丛覆盖下的土壤微生物群落与无灌丛覆盖的有显著差异(Nicol et al.,2003;Bachar et al.,2012)。灌丛覆盖下的土壤微生物群落总生物量,以及细菌和真菌等各类群的生物量均显著高于裸地(Ben-David et al.,2011;Yu et al.,2011;Bachar et al.,2012;Hortal et al.,2015),并随灌丛面积的增大而增加(Hortal et al.,2013)。Chen et al.(2015)进一步指出土壤微生物群落总生物量,及细菌和真菌的生物量均与地上植被的年净初级生产力相关,且呈驼峰型(hump-shaped)变化,即当地上植被的年净初级生产力在中等水平时,土壤微生物的生物量最大。与微生物生物量的分布特征类似,灌丛覆盖下细菌群落的物种多样性显著高于无灌丛覆盖的裸地(Bachar et al.,2012;Chen et al.,2015),且地上植被种类越多、丰富度越高,细菌群落的物种多样性也越高(Wang et al.,2015)。这主要是由于干旱半干旱区土壤养分匮乏,土壤资源富集于灌丛周围,土壤养分由灌丛向外逐步递减形成灌丛“肥岛”,使得灌丛下微生物的生物量及多样性显著高于无灌丛覆盖的地区。因此,干旱半干旱区地上植被与土壤微生物的空间分布格局之间存在耦合关系,即地上灌丛斑块状的分布格局导致地下微生物也呈现斑块状的分布格局(Herman et al.,1995;Ben-David et al.,2011;Bachar et al.,2012)。

此外,不同种类灌木的凋落物养分含量、冠幅形状及面积大小不同,使得不同种类的灌木对养分的积累程度不同。诸多研究强调了干旱半干旱区地上植被对微生物空间分布格局的影响与植物的种类密切相关(Saul-Tcherkas et al.,2009;Yu et al.,2011;Bainard et al.,2014;Hortal et al.,2015;Martirosyan et al.,2016)。

2.2 地理距离对干旱半干旱区土壤微生物空间分布格局具有显著影响

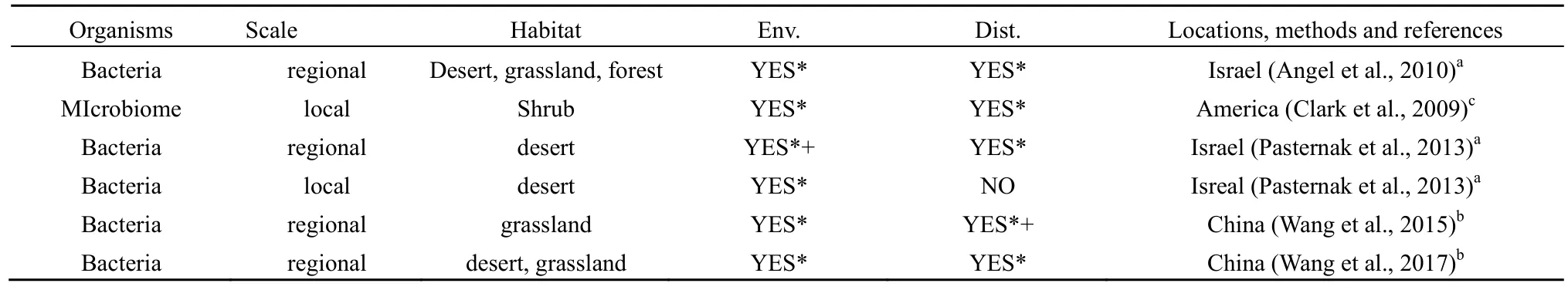

地理距离强调扩散限制对微生物空间分布格局的影响(Fierer,2008),表2总结了地理距离与干旱半干旱区土壤微生物空间分布格局关系的相关研究,结果表明,其他环境因素一致,地理距离是显著影响干旱半干旱区微生物的空间分布格局的重要因素,但二者作用的相对大小存在尺度效应。在较大的区域尺度下,地理距离是干旱半干旱区土壤微生物空间分布格局的决定性因素,而在较小的局域尺度上,主要受环境因素的影响。例如,Pasternak et al.(2013)的研究表明,在0.5~100 km的区域尺度上,地理距离显著影响细菌群落的分布格局,但在1 cm~500 m的局域尺度上,地理距离的影响不显著,而土壤质地、有机质含量及土壤含水率始终与细菌群落的分布呈显著相关。Wang et al.(2015)研究发现,在干旱半干旱区土壤细菌群落结构的相似性与地理距离及环境因素均呈显著负相关关系,说明环境因素及地理距离均是影响细菌群落分布格局的重要因素。方差分解分析结果表明,地理距离能解释 36.02%的差异,而环境因素只能解释24.06%的差异。因此,相较于环境因素,地理距离对土壤细菌群落的空间分布格局的影响作用更大。

表2 环境因素及地理距离对干旱半干旱区微生物群落的影响Table 2 The impacts of environmental factors (Env.) and geographic distances (Dist.) on soil microbial communities in arid and semi-arid regions

3 干旱半干旱区土壤微生物空间分布格局的形成机制

对干旱半干旱区土壤微生物空间分布格局及影响因素的研究,揭示了该类区域的微生物分布规律。在此基础上,目前仅有少数研究关注干旱半干旱区土壤微生物空间分布格局的形成机制。这类研究往往借鉴宏观生态学中的生态位理论、中性理论等,对干旱半干旱区土壤微生物空间分布格局的形成机制进行了探讨,为宏观理论在微生物生态学中的适用性研究提供了重要依据。

3.1 生态位理论及中性理论

生态位理论认为物种都有各自适应的环境,即生态位。在某环境中存在的物种都是最适应该环境的生物,不同的环境一定存在不同的物种,并且环境差异越大,物种组成的差异也就越大。所以,生态位理论强调确定性过程,如环境因素、生境间的异质性、物种间的相互作用等决定物种的存在及其相对丰度(Dumbrell et al.,2010;Ofiteru et al.,2010;Gilbert et al.,2012)。在微生物空间分布格局的研究中,生态位理论强调环境对微生物的选择作用(Vanwonterghem et al.,2014)。中性理论认为物种在生态上是等价的,即具有相同的出生、死亡、迁入和迁出的概率,随机的扩散等不确定性因素对群落结构具有决定性作用(Sloan et al.,2007)。尽管这两个理论表面上是对立的,但在对微生物空间分布格局进行解释时,这两个理论并不互相排斥(Chave,2010;Dumbrell et al.,2010)。许多研究结果表明,微生物空间分布格局是生态位理论及中性理论共同作用的结果(Bissett et al.,2010;Ofiteru et al.,2010;Burke et al.,2011;Caruso et al.,2011;Logares et al.,2013;Stegen et al.,2013)。

3.2 干旱半干旱区土壤微生物空间分布格局的形成机制具有生境依赖性

最新的研究开始尝试采用生态位理论及中性理论解释干旱半干旱区土壤微生物空间分布格局的成因。Wang et al.(2017)在4000 km区域尺度上的研究发现,干旱半干旱区土壤微生物空间分布格局的形成机制具有生境依赖性,即不同的生境中,微生物空间分布格局的形成机制不同。该研究发现在高寒草原生态系统(alphine grassland)中细菌群落的空间分布格局仅是确定性过程,即生态位理论作用的结果。而在荒漠生态系统(desert)中细菌群落的空间分布格局仅是随机性过程,即中性理论作用的结果,这可能是由于荒漠生态系统中生存的动物及植物非常有限,降低了微生物被动扩散的可能性,在这种情况下,扩散限制会成为影响微生物空间分布格局的决定性因素。

4 研究展望

在干旱半干旱区土壤微生物存在空间分布格局的研究基础上,通过分析环境因素及地理距离与微生物群落生物量、群落组成及个体丰度间的关系,了解影响干旱半干旱区土壤微生物的因素,进而探讨其空间分布格局的形成机制,以期为维持干旱半干旱区陆地生态系统的稳定性及生产力提供理论依据。从上述对目前研究结果的综述得知,,目前对干旱半干旱区土壤微生物的空间分布格局的影响因素及形成机制仍缺乏系统的认识,未来有待从以下4个方面,对该领域进行更加深入系统的研究。

(1)研究干旱半干旱区古菌及真菌的空间分布格局。对干旱半干旱区古菌及真菌的研究远滞后于细菌,而古菌及真菌在干旱胁迫下,会表现出与细菌完全不同的分布特征。这意味着,在干旱环境下,古菌与真菌空间分布格局的影响因素及驱动机制可能与细菌截然不同,有待进一步研究。这将为干旱半干旱区的生态修复,提供理论基础。

(2)扩大干旱半干旱区土壤微生物空间分布格局研究的空间尺度。在较小尺度上的研究,仅发现微生物存在空间分布格局,较难找出其分布规律,而扩大研究的空间尺度,能深入地揭示微生物分布格局的成因。比如,许多研究表明,pH对土壤细菌群落空间分布格局具有决定性作用,而干旱环境下的研究结果并不支持这一结论。这是因为在现有的研究中,pH值的变化范围比较小,掩盖了pH对微生物空间分布格局的影响作用;也有可能是因为在干旱环境下,土壤pH会影响微生物的空间分布,但不是决定性的因素。因此,还需要扩大研究的空间尺度做进一步研究。

(3)进一步研究干旱半干旱区土壤微生物空间分布格局的形成机制。目前大部分的研究仅关注干旱半干旱区土壤微生物空间分布格局及影响因素的现象描述,仅极少数研究应用生态理论及中性理论对其成因进行解释。而这些少量研究所获得的结论,存在一定的片面性。这些问题是源于研究技术手段、研究尺度等,还是源于干旱半干旱区特有现象,都需要进一步研究。

(4)研究干旱半干旱区土壤微生物与植物群落空间分布格局的耦合关系。植物可以通过对土壤营养输入、内生菌、根际微生物等影响土壤微生物群落。微生物群落可以通过分解凋落物、调控土壤的营养来影响地上植物的生长。两者相互影响、相互改变,共同驱动各自群落结构的改变。土壤微生物群落与植物群落是否存在耦合的空间分布格局,一直是生态学中的研究热点。在干旱半干旱区出现“肥岛效应”的独特环境下,比较该区土壤微生物及植物群落的空间分布格局及影响因素,有助于理解土壤微生物及植物空间分布格局间的联系。

ANGEL R, CONRAD R. 2013. Elucidating the microbial resuscitation cascade in biological soil crusts following a simulated rain event [J].Environmental Microbiology, 15(10): 2799-2815.

ANGEL R, SOARES M I M, UNGAR E D, et al. 2010. Biogeography of soil archaea and bacteria along a steep precipitation gradient [J]. The ISME Journal, 4(4): 553-563.

ARMSTRONG A, VALVERDE A, RAMOND J, et al. 2016. Temporal dynamics of hot desert microbial communities reveal structural and functional responses to water input [J]. Scientific Reports, 6: 34434.

BACHAR A, AL-ASHHAB A, SOARES M I M, et al. 2010. Soil Microbial Abundance and Diversity Along a Low Precipitation Gradient [J].Microbial Ecology, 60(2): 453-461.

BACHAR A, SOARES M I M, GILLOR O. 2012. The Effect of Resource Islands on Abundance and Diversity of Bacteria in Arid Soils [J].Microbial Ecology, 63(3): 694-700.

BAINARD L D, BAINARD J D, HAMEL C, et al. 2014. Spatial and temporal structuring of arbuscular mycorrhizal communities is differentially influenced by abiotic factors and host crop in a semi-arid prairie agroecosystem [J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 88(2):333-344.

BARNARD R L, OSBORNE C A, FIRESTONE M K. 2013. Responses of soil bacterial and fungal communities to extreme desiccation and rewetting [J]. The ISME Journal, 7(11): 2229-2241.

BASTIDA F, HERNÁNDEZ T, GARCÍA C. 2014. Metaproteomics of soils from semiarid environment: Functional and phylogenetic information obtained with different protein extraction methods [J]. Journal of Proteomics, 101(7): 31-42.

BASTIDA F, MORENO J L, HERNANDEZ T, et al. 2006. Microbiological degradation index of soils in a semiarid climate [J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 38(12): 3463-3473.

BASTIDA F, TORRES I F, MORENO J L, et al. 2016. The active microbial diversity drives ecosystem multifunctionality and is physiologically related to carbon availability in Mediterranean semi-arid soils [J].Molecular Ecology, 25(18): 4660-4673.

BECKING L G M B. 1934. Geobiologie of inleiding tot de milieukunde[M]. The Hague: W P Van Stockum and Zoon.

BELL C W, ACOSTA-MARTINEZ V, MCINTYRE N E, et al. 2009.Linking Microbial Community Structure and Function to Seasonal Differences in Soil Moisture and Temperature in a Chihuahuan Desert Grassland [J]. Microbial Ecology, 58(4): 827-842.

BELL C W, TISSUE D T, LOIK M E, et al. 2014. Soil microbial and nutrient responses to 7 years of seasonally altered precipitation in a Chihuahuan Desert grassland [J]. Global Change Biology, 20(5):1657-1673.

BELL C, MCINTYRE N, COX S, et al. 2008. Soil microbial responses to temporal variations of moisture and temperature in a Chihuahuan Desert Grassland [J]. Microbial Ecology, 56(1): 153-167.

BEN-DAVID E A, ZAADY E, SHER Y, et al. 2011. Assessment of the spatial distribution of soil microbial communities in patchy arid and semi-arid landscapes of the Negev Desert using combined PLFA and DGGE analyses [J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 76(3): 492-503.

BISSETT A, RICHARDSON A E, BAKER G, et al. 2010. Life history determines biogeographical patterns of soil bacterial communities over multiple spatial scales [J]. Molecular Ecology, 19(19): 4315-4327.

BURKE C, STEINBERG P, RUSCH D, et al. 2011. Bacterial community assembly based on functional genes rather than species [J].Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(34): 14288-14293.

BURKE E J, BROWN S J, CHRISTIDIS N. 2006. Modeling the Recent Evolution of Global Drought and Projections for the Twenty-First Century with the Hadley Centre Climate Model [J]. Journal of Hydrometeorology, 7(5): 1113-1125.

CARUSO T, CHAN Y, LACAP D C, et al. 2011. Stochastic and deterministic processes interact in the assembly of desert microbial communities on a global scale [J]. The ISME Journal, 5(9): 1406.

CASTRO H F, CLASSEN A T, AUSTIN E E, et al. 2010. Soil microbial community responses to multiple experimental climate change drivers[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 76(4): 999-1007.

CHAVE J. 2010. Neutral theory and community ecology [J]. Ecology Letters, 7(3): 241-253.

CHEN D, MI J, CHU P, et al. 2015. Patterns and drivers of soil microbial communities along a precipitation gradient on the Mongolian Plateau[J]. Landscape Ecology, 30(9): 1669-1682.

CHU H, FIERER N, LAUBER C L, et al. 2010. Soil bacterial diversity in the Arctic is not fundamentally different from that found in other biomes [J]. Environmental Microbiology, 12(11): 2998-3006.

CLARK J S, CAMPBELL J H, GRIZZLE H, et al. 2009. Soil Microbial Community Response to Drought and Precipitation Variability in the Chihuahuan Desert [J]. Microbial Ecology, 57(2): 248-260.

CREGGER M A, SCHADT C W, MCDOWELL N G, et al. 2012. Response of the Soil Microbial Community to Changes in Precipitation in a Semiarid Ecosystem [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology,78(24): 8587-8594.

DAI A. 2013. Increasing drought under global warming in observations and models [J]. Nature Climate Change, 3(1): 52-58.

DE DEYN G B, VAN DER PUTTEN W H. 2005. Linking aboveground and belowground diversity [J]. Trends in Ecology and Evolution,20(11): 625-633.

DE W R, BOUVIER T. 2006. 'Everything is everywhere, but, the environment selects'; what did Baas Becking and Beijerinck really say? [J]. Environmental Microbiology, 8(4): 755-758.

DUMBRELL A J, NELSON M, HELGASON T, et al. 2010. Relative roles of niche and neutral processes in structuring a soil microbial community [J]. The ISME Journal, 4(3): 337-345.

DUNBAR J, TAKALA S, BARNS S M, et al. 1999. Levels of bacterial community diversity in four arid soils compared by cultivation and 16S rRNA gene cloning [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology,65(4): 1662-1669.

EVANS R D, JOHANSEN J R. 1999. Microbiotic crusts and ecosystem processes [J]. Critical Reviews in Plant Science, 18(2): 183-225.

EVENARI M, SHANAN L, TADMOR N. 1982. The Negev: the challenge of a desert [M]. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

FERRIER S, POWELL G V, RICHARDSON K S, et al. 2004. Mapping more of terrestrial biodiversity for global conservation assessment [J].Bioscience, 54(12): 1101-1109.

FIERER N, CARNEY K M, HORNER-DEVINE M C, et al. 2009. The biogeography of ammonia-oxidizing bacterial communities in soil [J].Microbial Ecology, 58(2): 435-445.

FIERER N, JACKSON J A, VILGALYS R, et al. 2005. Assessment of soil microbial community structure by use of taxon-specific quantitative PCR assays [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 71(7):4117-4120.

FIERER N, JACKSON R B. 2006. The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 103(3): 626-631.

FIERER N, LADAU J. 2012. Predicting microbial distributions in space and time [J]. Nature Methods, 9(6): 549-551.

FIERER N, LEFF J W, ADAMS B J, et al. 2012. Cross-biome metagenomic analyses of soil microbial communities and their functional attributes [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(52): 21390-21395.

FIERER N. 2008. Microbial biogeography: patterns in microbial diversity across space and time [J]. Accessing Uncultivated Microorganisms:from the Environment to Organisms and Genomes and Back: 95-115.

FLIESBACH A, SARIG S, STEINBERGER Y. 1994. Effects of water pulses and climatic conditions on microbial biomass kinetics and microbial activity in a Yermosol of the central Negev [J]. Arid Land Research and Management, 8(4): 353-362.

FU Q, FENG S. 2014. Responses of terrestrial aridity to global warming[J]. Journal of Geophysical Research Atmospheres, 119: 7863-7875.

GILBERT J A, STEELE J A, CAPORASO J G, et al. 2012. Defining seasonal marine microbial community dynamics [J]. The ISME Journal, 6(2): 298.

GREEN J L, HOLMES A J, WESTOBY M, et al. 2004. Spatial scaling of microbial eukaryote diversity [J]. Nature, 432(7018): 747-750.

GREEN J, BOHANNAN B J M. 2006. Spatial scaling of microbial biodiversity [J]. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 21(9): 501-507.

GRIFFITHS R I, THOMSON B C, JAMES P, et al. 2011. The bacterial biogeography of British soils [J]. Environmental Microbiology, 13(6):1642-1654.

GUNNIGLE E, FROSSARD A, RAMOND J B, et al. 2017. Diel-scale temporal dynamics recorded for bacterial groups in Namib Desert soil[J]. Scientific reports, 7: 40189.

HAGEMANN M, HENNEBERG M, FELDE V J M N, et al. 2015.Cyanobacterial Diversity in Biological Soil Crusts along a Precipitation Gradient, Northwest Negev Desert, Israel [J]. Microbial Ecology, 70(1): 219-230.

HERMAN R P, PROVENCIO K R, HERRERAMATOS J, et al. 1995.Resource islands predict the distribution of heterotrophic bacteria in chihuahuan desert soils [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology,61(5): 1816-1821.

HOLMES A. 2000. Diverse, yet-to-be-cultured members of the Rubrobacter subdivision of the Actinobacteria are widespread in Australian arid soils [J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 33(2): 111-120.HORTAL S, BASTIDA F, ARMAS C, et al. 2013. Soil microbial community under a nurse-plant species changes in composition,biomass and activity as the nurse grows [J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 64: 139-146.

HORTAL S, BASTIDA F, MORENO J L, et al. 2015. Benefactor and allelopathic shrub species have different effects on the soil microbial community along an environmental severity gradient [J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 88: 48-57.

HU Y, XIANG D, VERESOGLOU S D, et al. 2014. Soil organic carbon and soil structure are driving microbial abundance and community composition across the arid and semi-arid grasslands in northern China[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 77(1): 51-57.

HUANG G, LI Y, SU Y G. 2015. Effects of increasing precipitation on soil microbial community composition and soil respiration in a temperate desert, Northwestern China [J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 83:52-56.

JANSSEN P H. 2006. Identifying the dominant soil bacterial taxa in libraries of 16S rRNA and 16S rRNA genes [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 72(3): 1719-1728.

JESUS E D C, MARSH T L, TIEDJE J M, et al. 2009. Changes in land use alter the structure of bacterial communities in Western Amazon soils[J]. The ISME Journal, 3(9): 1004-1011.

JONES R T, ROBESON M S, LAUBER C L, et al. 2009. A comprehensive survey of soil acidobacterial diversity using pyrosequencing and clone library analyses [J]. The ISME Journal, 3(4): 442-453.

KIM M, BOLDGIV B, SINGH D, et al. 2013. Structure of soil bacterial communities in relation to environmental variables in a semi-arid region of Mongolia [J]. Journal of Arid Environments, 89: 38-44.

LAUBER C L, HAMADY M, KNIGHT R, et al. 2009. Pyrosequencingbased assessment of soil pH as a predictor of soil bacterial community structure at the continental scale [J]. Applied & Environmental Microbiology, 75(15): 5111-5120.

LI M, LI Y, CHEN W F, et al. 2012. Genetic diversity, community structure and distribution of rhizobia in the root nodules of Caragana spp. from arid and semi-arid alkaline deserts, in the north of China [J].Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 35(4): 239-245.

LOGARES R, LINDSTRÖM E S, LANGENHEDER S, et al. 2013.Biogeography of bacterial communities exposed to progressive long-term environmental change [J]. The ISME Journal, 7(5): 937.

LOZUPONE C A, KNIGHT R. 2007. Global patterns in bacterial diversity[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(27): 11436-11440.

MAESTRE F T, DELGADO-BAQUERIZO M, JEFFRIES T C, et al. 2015.Increasing aridity reduces soil microbial diversity and abundance in global drylands [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(51): 15684-15689.

MARTIROSYAN V, UNC A, MILLER G, et al. 2016. Desert Perennial Shrubs Shape the Microbial-Community Miscellany in Laimosphere and Phyllosphere Space [J]. Microbial Ecology, 72(3): 659-668.

NAVARRO-GONZALEZ R. 2003. Mars-Like Soils in the Atacama Desert,Chile, and the Dry Limit of Microbial Life [J]. Science, 302(5647):1018-1021.

NEILSON J W, QUADE J, ORTIZ M, et al. 2012. Life at the hyperarid margin: novel bacterial diversity in arid soils of the Atacama Desert,Chile [J]. Extremophiles, 16(3): 553-566.

NICOL G W, GLOVER L A, PROSSER J I. 2003. Spatial Analysis of Archaeal Community Structure in Grassland Soil [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 69(12): 7420-7429.

NIEDERBERGER T D, SOHM J A, GUNDERSON T E, et al. 2015.Microbial community composition of transiently wetted Antarctic Dry Valley soils [J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 6(9): 1-12

NISHIYAMA M, SUMIKAWA Y, GUAN G, et al. 2001. Relationship between microbial biomass and extractable organic carbon content in volcanic and non-volcanic ash soil [J]. Applied Soil Ecology, 17(2):183-187.

NOY-MEIR I. 1979. Structure and function of desert ecosystems [J]. Israel Journal of Botany, 28(1): 1-19.

OFITERU I D, LUNN M, CURTIS T P, et al. 2010. Combined niche and neutral effects in a microbial wastewater treatment community [J].Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(35): 15345.

O'MALLEY M A. 2008. ‘Everything is everywhere: but the environment selects’: ubiquitous distribution and ecological determinism in microbial biogeography [J]. Studies in History & Philosophy of Science Part C Studies in History & Philosophy of Biological &Biomedical Sciences, 39(3): 314-325.

PAJARES S, ESCALANTE A E, NOGUEZ A M, et al. 2016. Spatial heterogeneity of physicochemical properties explains differences in microbial composition in arid soils from Cuatro Cienegas, Mexico [J].Peerj, 4: e2459.

PASTERNAK Z, AL-ASHHAB A, GATICA J, et al. 2013. Spatial and Temporal Biogeography of Soil Microbial Communities in Arid and Semiarid Regions [J]. Plos One, 8(7): e69705.

POINTING S B, BELNAP J. 2012. Microbial colonization and controls in dryland systems [J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 10(8): 551-562.

RALTE V, PANDEY H N, BARIK S K, et al. 2005. Changes in microbial biomass and activity in relation to shifting cultivation and horticultural practices in subtropical evergreen forest ecosystem of north-east India[J]. Acta Oecologica, 28(2): 163-172.

RAMETTE A, TIEDJE J M. 2007. Biogeography: An Emerging Cornerstone for Understanding Prokaryotic Diversity, Ecology, and Evolution [J]. Microbial Ecology, 53(2): 197-207.

RAO S, CHAN Y, BUGLER-LACAP D C, et al. 2016. Microbial Diversity in Soil, Sand Dune and Rock Substrates of the Thar Monsoon Desert,India [J]. Indian Journal of Microbiology, 56(1): 35-45.

REYNOLDS J F, SMITH D M S, LAMBIN E F, et al. 2007. Global Desertification: Building a Science for Dryland Development [J].Science, 316(5826): 847-851.

SAFRIEL U N, ADEEL Z. 2005. Dryland Systems [C] HASSAN I R,SCHOLES R, ASH N. Ecosystems and human well-being: current state and trends. Washington: Island Press: 623-662.

SARIG S, FLIESSBACH A, STEINBERGER Y. 1996. Microbial biomass reflects a nitrogen and phosphorous economy of halophytes grown in salty desert soil [J]. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 21(1): 128-130.

SAUL-TCHERKAS V, STEINBERGER Y. 2009. Substrate utilization patterns of desert soil microbial communities in response to xeric and mesic conditions [J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 41(9): 1882-1893.

SAUL-TCHERKAS V, STEINBERGER Y. 2011. Soil microbial diversity in the vicinity of a Negev Desert shrub-Reaumuria negevensis [J].Microbial Ecology, 61(1): 64-81.

SAUL-TCHERKAS V, UNC A, STEINBERGER Y. 2013. Soil Microbial Diversity in the Vicinity of Desert Shrubs [J]. Microbial Ecology,65(3): 689-699.

SCHLESINGER W H, REYNOLDS J F, CUNNINGHAM G L, et al. 1990.Biological feedbacks in global desertification [J]. Science(Washington), 247(4946): 1043-1048.

SLOAN W T, WOODCOCK S, LUNN M, et al. 2007. Modeling Taxa-Abundance Distributions in Microbial Communities using Environmental Sequence Data [J]. Microbial Ecology, 53(3): 443-455.STEGEN J C, LIN X, FREDRICKSON J K, et al. 2013. Quantifying community assembly processes and identifying features that impose them[J]. The ISME Journal, 7(11): 2069-2079.

STEVEN B, GALLEGOS-GRAVES L V, BELNAP J, et al. 2013. Dryland soil microbial communities display spatial biogeographic patterns associated with soil depth and soil parent material [J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 86(1): 101-113.

STUART S N, CHANSON J S, COX N A, et al. 2004. Status and trends of amphibian declines and extinctions worldwide [J]. Science, 306(5702):1783-1786.

TAKETANI R G, KAVAMURA V N, MENDES R, et al. 2015. Functional congruence of rhizosphere microbial communities associated to leguminous tree from Brazilian semiarid region [J]. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 7(1): 95-101.

TAKETANI R G, LANCONI M D, KAVAMURA V N, et al. 2017. Dry Season Constrains Bacterial Phylogenetic Diversity in a Semi-Arid Rhizosphere System [J]. Microbial Ecology, 73(1): 153-161.

TANIGUCHI T, USUKI H, KIKUCHI J, et al. 2012. Colonization and community structure of root-associated microorganisms of Sabina vulgaris with soil depth in a semiarid desert ecosystem with shallow groundwater [J]. Mycorrhiza, 22(6): 419-428.

TRIPATHI B M, MOROENYANE I, Sherman C, et al. 2017. Trends in Taxonomic and Functional Composition of Soil Microbiome Along a Precipitation Gradient in Israel [J]. Microbial Ecology, 74(1): 168-176.TSIKNIA M, PARANYCHIANAKIS N V, VAROUCHAKIS E A, et al.2014. Environmental drivers of soil microbial community distribution at the Koiliaris Critical Zone Observatory [J]. FEMS microbiology ecology, 90(1): 139-152.

VALVERDE A, MAKHALANYANE T P, SEELY M, et al. 2015.Cyanobacteria drive community composition and functionality in rock–soil interface communities [J]. Molecular Ecology, 24(4): 812-821.

VANWONTERGHEM I, JENSEN P D, DENNIS P G, et al. 2014.Deterministic processes guide long-term synchronised population dynamics in replicate anaerobic digesters [J]. The ISME Journal,8(10): 2015-2028.

WAKELIN S A, ANAND R R, REITH F, et al. 2012. Bacterial communities associated with a mineral weathering profile at a sulphidic mine tailings dump in arid Western Australia [J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 79(2): 298-311.

WANG X B, LÜ X T, YAO J, et al. 2017. Habitat-specific patterns and drivers of bacterial β-diversity in China's drylands [J]. The ISME Journal, 11: 1345-1358.

WANG X, VAN NOSTRAND J D, DENG Y, et al. 2015. Scale-dependent effects of climate and geographic distance on bacterial diversity patterns across northern China's grasslands [J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 91(12): 1-10.

WARDLE D A, BARDGETT R D, KLIRONOMOS J N, et al. 2004.Ecological linkages between aboveground and belowground biota [J].Science, 304(5677): 1629-163.

WHITFORD W G. 2002. Ecology of Desert Systems [M]. New York,London: Academic Press.

YAO M, RUI J, NIU H, et al. 2017. The differentiation of soil bacterial communities along a precipitation and temperature gradient in the eastern Inner Mongolia steppe [J]. Catena, 152: 47-56.

YU J, STEINBERGER Y. 2011. Vertical Distribution of Microbial Community Functionality under the Canopies of Zygophyllum dumosum and Hammada scoparia in the Negev Desert, Israel [J].Microbial Ecology, 62(1): 218-227.

ZEGLIN L H, DAHM C N, BARRETT J E, et al. 2011. Bacterial Community Structure Along Moisture Gradients in the Parafluvial Sediments of Two Ephemeral Desert Streams [J]. Microbial Ecology,61(3): 543-556.

ZHAO C, MIAO Y, YU C, et al. 2016. Soil microbial community composition and respiration along an experimental precipitation gradient in a semiarid steppe [J]. Scientific Reports, 6: 24317.