天然水体中两种主要异嗅物质的来源及迁移转化研究进展

李冲炜, 邹 攀, 杨兆光,2, 李海普*

(1.中南大学 化学化工学院,湖南 长沙 410083;2.中南大学 深圳研究院,广东 深圳 518057)

天然水体中两种主要异嗅物质的来源及迁移转化研究进展

李冲炜1, 邹 攀1, 杨兆光1,2, 李海普1*

(1.中南大学 化学化工学院,湖南 长沙 410083;2.中南大学 深圳研究院,广东 深圳 518057)

近年来,水中嗅味问题逐渐引起关注。研究发现,天然水体中异嗅物质主要是微生物和藻类的挥发性次级代谢产物。总结了天然水体中常见的两种异嗅物质土臭素(GSM) 和二甲基异莰醇(MIB)的来源及其在生物体内的合成途径。介绍了异嗅物质通过吸附、挥发、光解、生物降解等一系列作用在饮用水水源中的迁移转化以及其进入水体生物的途径。

挥发性次级代谢产物;异嗅物质;二甲基异莰醇;土臭素;归趋

异嗅是指人的感觉器官(鼻)所感知的异常或令人讨厌的气味。湖泊、河流等水源中常见的异嗅物质主要是土霉味的土臭素(geosmin,GSM)和二甲基异莰醇(2-methylisoborneol,MIB)。此类物质在很低的浓度水平下即可令人感知到相关异嗅的存在(MIB为5~10 ng/L,GSM为1~10 ng/L)[1]。随着生活水平的不断提高,人们对饮用水、水产品质量的要求越来越高。据相关统计,异嗅已成为自来水消费者投诉比例最高的一类问题[2]。国外从20世纪50年代就开始对水体异嗅的研究,已成为当今世界水环境研究热点之一。而我国在该方面的研究相对较晚,相关研究工作也较少,仅近几年来关于太湖、黄浦江、武汉东湖、北京景观湖泊等水体异嗅现象才有一些文献报道[3-5]。随着我国水体富营养化日益严重,饮用水的异嗅问题也日渐突出。如齐飞等[5]对北京9处典型景观湖泊水体嗅味污染特征进行研究发现,这9处水体中MIB和GSM平均浓度高达613.84和319.57 ng/L。研究异嗅物质的来源与迁移转化可以更好地对异嗅物质进行控制和预测。

1 异嗅物质的主要来源与合成机制

1.1 异嗅物质的主要来源及影响因素

早在1891年,Berthelot等发现土壤中引起土霉味的物质能够从土壤中蒸馏出来并且可能是中性的,但是他们并不知道这些物质是怎样产生的[6]。当微生物纯培养技术出现时,人们将对于这种异嗅物质来源研究的目光投向了放线菌[7]。此后,大量的研究证明了放线菌确实能够产生异嗅物质,但是对于异嗅物质的结构并没有研究[8-9]。1963年,Gaines等[10]对链霉菌属的代谢产物进行研究后提出假设,异嗅物质是一些小分子化合物的组合,如醋酸、乙醛、乙醇、异丁醇等。1965年,Gerber等[7]最早从链霉菌属等放线菌中分离并提纯出一种异嗅物质,将其命名为Geosmin,ge在希腊语中的意思是土地,而osmin的意思是味道。1969年,Medsker等[11]从放线菌培养物中分离出另一种常见的土霉味物质MIB。因而,人们对土霉味物质MIB和GSM来源的研究最初主要集中在放线菌上。

1967,Safferman等[12]在Symplocaniuscorum属丝状蓝藻菌IU 617存储培养的常规转移中检测到一种土霉味物质,其味道与之前文献发现放线菌产生的嗅味相同。因此,蓝藻菌也被认为是异嗅物质的来源之一,直到1976年Tabachek等[13]调查发现蓝藻菌可能是比放线菌更频繁的来源。后来,越来越多的文献调查发现在能进行光合作用的水体环境中,蓝藻是MIB和GSM的主要来源[14-16]。Izaguirre等[17]从1990年至1992年对美国金字塔湖进行连续三年的调查,发现约40种蓝藻菌能够产生MIB和GSM,主要包括浮游的项圈藻、束丝藻属、假鱼腥藻属、水底席藻属、颤藻属和林氏藻属等。目前,共发现有2 000余种蓝藻菌能够产生MIB和GSM[18]。

一些研究常常把微生物数目做为异嗅物质追踪的办法。如有研究发现淡水湖中GSM的季节性浓度和束丝藻属的数目有着正相关的关系[19],而Jones等[20]在对澳大利亚的Hay Weir坝和Carcoar坝的研究中发现,对于项圈藻也有着相似的结果。但是也有文献报道,项圈藻的数目与异嗅物质的浓度相关性并不大[21]。除此之外,有文献报道在同一水体中不同的水层中异嗅物质的浓度也存在极大的不同:在好氧的湖面温水层(Oxic epilimnion)GSM的浓度为50 ng/L,而在缺氧的湖底静水层(Anoxic hypolimnion)GSM的浓度则高达950 ng/L[22]。大量的研究发现,在实验室环境下MIB和GSM在放线菌及蓝藻中的产率主要与光照强度、温度、氧含量及离子强度等有关[23-29]。如Dionigi等[26]研究了温度对链霉菌生长和产生GSM的影响,发现链霉菌在30~45 ℃时比在15~20 ℃时培养2 d产生的GSM量大。Saadoun等[25]对不同温度和光照强度下项圈藻属的培养发现,在20 ℃、光强度为17 μE/m2/s时,GSM量/生物量达到了最大;而在一定温度下,GSM量/叶绿素a量与光照强度呈正相关(r2=0.95),也就是说在一定的温度下,增加光照强度会减少叶绿素a的合成而增加GSM的合成。但是没有研究能够独立解释在天然环境中异嗅物质的产率有如此巨大的不同。可见,MIB和GSM的产生是一个很复杂的现象,受不同环境因素的影响,不能单纯把微生物数目或其他某一因素当做影响异嗅物质浓度的唯一指标。

除受光照、温度及离子强度等因素影响外,异嗅物质的产生还受许多其他因素的影响。1985年,Wood等[30]发现水库中的微白黄链霉菌需在有沉淀物质或者植物残骸等营养物质存在的条件下才能产生MIB。随后,Sugiura等[31]发现沉淀蓝藻和硅藻细胞也能为水底链霉菌产生挥发性有机物(VOCs)提供很好的底物。也有研究发现在放线菌的生长阶段与非生长阶段异嗅物质的产量也存在巨大的差异[32]。

1.2 异嗅物质的生物合成机制

1981年,Bentley等[33]对链霉菌属进行放射性标记实验,在培养过程中加入含有放射性醋酸铅,在两种物质中都检测到了示踪元素,由此认为存在异戊二烯的合成过程。后续在培养液中加入带有示踪元素甲基的蛋氨酸,在MIB中也发现了示踪元素。最后得出结论:MIB是带有甲基的单萜,GSM是失去了异丙基的倍半萜烯。

早期,在放线菌中的放射性实验都未能成功地得出GSM的生物合成路径,在蓝藻菌中的研究也是如此。虽然Cane等研究证明法尼基焦磷酸是环状倍半萜烯的直接前体[34],但是早前的实验显示在培养中加入法尼醇会抑制细菌和蓝藻菌的生长[35-36]。因此,法尼焦磷酸不能用作合成路径研究的工具。直到近十年,其他合成前体的使用,才使GSM在放线菌中合成的研究有了重大进展[37]。

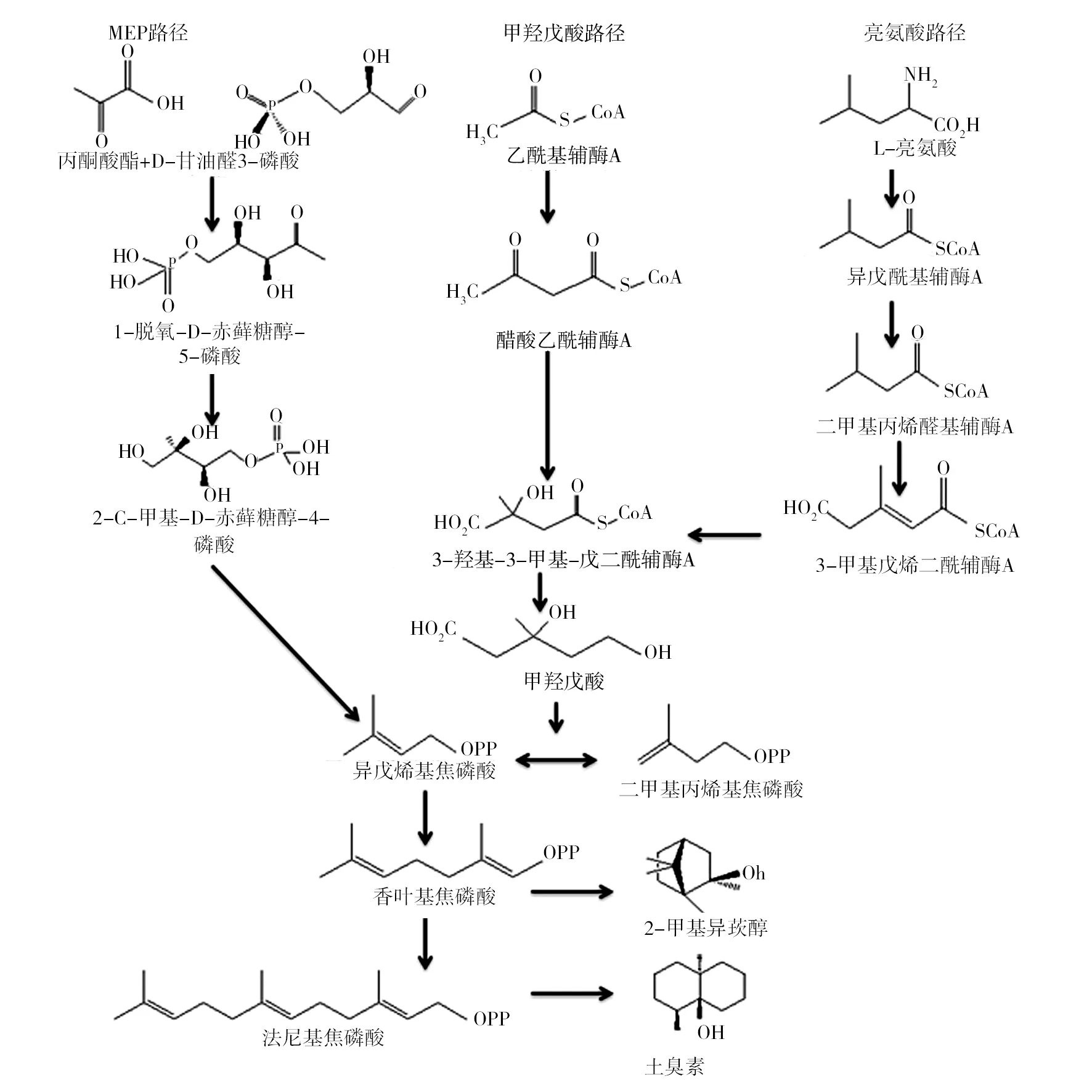

Juttner等[37]综合总结了大量的放射性标记实验和基因实验,对在微生物合成类异戊二烯(主要是GSM)途径做出了以下总结(图1):GSM的合成主要分为3个路径,即2-甲基赤藓糖醇-4-磷酸( 2-methylerythritol-4-phosphate,MEP) 路径、甲羟戊酸( mevalonate,MVA) 路径和L-亮氨酸路径,MEP合成是最重要的一个路径。Spitelle等[38]的实验结果显示:当给予被氘化的脱氧木酮糖([5,4-2H2]1-deoxy-D-xylulose)而非甲羟戊酸内酯([4,4,6,6,6-2H5]mevalolactone) 时,链霉菌可产生被氘化的GSM,也验证了MEP路径是主要的合成路径。这个合成已经从基因学和酶催化的角度在高等植物体内得到很合理的解释[39]。对于GSM在蓝藻菌体内的合成,MEP合成路径的基因密码已经在集胞藻属PCC6803体内被发现[40]。虽然这种藻类并没有发现能够产生GSM,但从侧面说明在能够产生GSM的蓝藻中有着相同的类异戊二醇合成路径。

虽然在许多细菌群中,MEP路径是主要合成类异戊二醇的路径,但是有研究发现在微生物体内同时存在MVA合成路径[36]。有研究表明,在一些链霉菌的活跃生长阶段主要是MEP路径,而在静止生长阶段主要是MVA路径[41-42]。粘细菌也是一种主要应用MVA路径合成GSM的微生物,但是在这种微生物体内还存在一个以L-亮氨酸为开始的次要合成路径[43]。

MIB的生物合成途径直到2007年才被发现。Dickschat等[44]用示踪前体蛋氨酸([methyl-13C]methionine)喂养不同株系的粘细菌——侵蚀侏囊菌(Nannocystisexedens),对培养液的GC/MS分析显示,源自蛋氨酸的甲基被渗入到MIB中,其剩余的10个碳原子则由叶基焦磷酸(geranyl diphosphate,GPP,C10)衍生而来,即GPP甲基化形成新的生物合成中间体2-methyl-GPP,再经环化形成MIB。

图1 MIB和GSM在链霉菌和粘细菌中产生的简化合成图

2 异嗅物质的迁移转化

2.1 异嗅物质从微生物胞内到胞外的转移

蓝藻菌属在生长阶段合成的这两种物质是储存在细胞体内还是释放出来取决于微生物的生长阶段和环境因素,大多数的异嗅物质在蓝藻菌死亡后通过生物降解释放出来[45]。Juttner等[37]认为这种现象能够发生,是因为异嗅物质本身相对于异嗅物质生产者的其他细胞成分来说,更不容易被水中的大部分细菌降解。

Durrer等[46]的研究发现,当束丝藻(Aphanizomenongracile)被甲壳纲动物低额蚤(Simocephalus)或水蚤(Daphniamagna)擦伤后,细胞体内的GSM几乎完全释放出来[46]。因此,除了蓝藻菌死亡后被降解释放出异嗅物质外,一些水底食草类动物的食草活动也会使异嗅物质从蓝藻体内大量地释放出来。

2.2 异嗅物质在天然水体中的迁移转化

有机污染物在水环境中一般通过生物降解作用、挥发作用、光解作用、吸附作用等过程进行迁移转化[47]。对于MIB和GSM生物降解的研究最早始于1970年[48]。比较早期的一些文献主要报道了能够对MIB和GSM这两种物质进行生物降解的微生物的分离和鉴定(表1)。

表1 能够对MIB和GSM进行降解的微生物[49]

Table 1 Microorganisms implicated in the biodegradation of GSM and MIB

MIBGSM微生物参考文献微生物参考文献Pseudomonasspp.[50⁃52]Bacilluscereus[48,58]Pseudomonasaeruginosa[51]Bacillussubtilis[57⁃58]Pseudomonasputida[53]Arthrobacteratrocyaneus[59]Enterobacterspp.[52]Arthrobacterglobiformis[59]Candidaspp.[54]Rhodococcusmoris[59]Flavobacteriummultivorum[51] Chlorophenolicus strainN⁃1053[59] Flavobacteriumspp.[51]Bacillusspp.[55⁃56]Bacillussubtilis[57]

有文献报道MIB和GSM能被自来水厂砂滤过程中的假单胞菌和鞘氨醇单胞菌降解[60-62]。Aoyama等[63]和Lupton等[64]发现假单胞菌与项圈藻属是共存体。所以,生物降解作用可能是影响水中异嗅物质浓度的最重要的作用。

Trudgill[65]和Rittmann等[66]认为MIB和GSM能够被降解是因为他们有着与醇和酮相似的结构。仅有东京某一科研机构对于MIB和GSM的代谢产物结构进行了研究。Tanaka等[52]利用气相-质谱联用(GC-MS)对MIB的脱水产物进行鉴定,结果显示有两种可能的脱水产物:2-甲基莰烯和2-甲基烯莰烷,认为MIB的代谢途径可能与莰酮相似。对于GSM,Saito等分析鉴定有4种可能的代谢产物,其中两种被鉴定为1,4a-二甲基-2,3,4,4a,5,6,7,8-八氢萘(1,4a-dimethyl-2,3,4,4a,5,6,7,8-octahydronaphthalene)和烯酮,这两种物质同时也能用于GSM的化学合成。同时,他们认为GSM的代谢途径可能与环己醇相似[67]。到目前为止,对这两种物质的生物降解途径都没有明确的依据。

Westerhoff等[68]通过对美国Bartlett、Saguaro、Pleasant三大湖的研究发现,MIB和GSM的生物降解符合伪零及动力学模型,其生物降解率在0.8~1.2 ng/(L·d)之间。然而,Rittmann等[65]却认为MIB和GSM在自然水体中被当做二级底物使用是因为自然水体中天然有机物(NOM)的浓度远远高于这两种物质的浓度,因此认为这两种物质的在天然水体中的生物降解符合二级动力学模型。

MIB和GSM能够发生光解,MIB和GSM在高强度紫外光照下的直接和催化光解有了大量的研究,这两种物质在中压10 000 J/m2紫外灯照射下能达到20%以上的去除率,当加入5 mg/L的H2O2时,去除率能达到40%以上;当紫外强度提高到101 000 J/m2并加入适当的H2O2或臭氧时,几乎能够全部去除MIB和GSM[72-74]。但没有文献对这两种物质的阳光直射光解进行定量研究报道。李林等[75]将MIB溶液在冰浴条件下进行阳光直射3 h,并在暗室条件下做对照试验,发现MIB的光解几乎可以忽略。

利用粉末活性炭对MIB和GSM进行吸附是目前水厂比较常用的一种去除这两种异嗅物质的方法。但是在常常发生异嗅物质污染的水体如水库和湖泊中,水体比较澄清,吸附作用不太明显[68]。此外,水体中存在的较高浓度天然有机物(NOM)对浓度较低的MIB和GSM产生竞争吸附,使得水体中的悬浮颗粒对MIB和GSM的吸附效率变低[76]。

2.3 异嗅化合物进入水产动物体内的途径

水体中某些能够引起异嗅的化学物质会进入水产动物体内,其主要途径包括通过动物的鳃及皮肤吸收和通过摄食被水产动物肌肉吸收[77]。异嗅物质发生渗透主要通过水产动物的鳃还是通过摄食吸收取决于异嗅物质的辛烷/水分配系数(KOW)。当log KOW低于6时,主要通过鳃吸收,大于6时主要通过摄食吸收[78]。而MIB和GSM的log KOW分别为3.31和3.57,因此这两种物质主要通过鳃吸收[79]。异嗅物质通过鳃吸收进入鱼体内是可逆的,当将含有异嗅的鱼放入清水中时,异嗅物质就会从鱼体内进入到水中,但其速度要比进入鱼体内慢的多,完全去除异嗅需要几天[7]。

3 展 望

水中异嗅物质的研究是一个多学科交叉研究领域,涉及分析化学、生态学、基因学、化学动力学、统计数学及湖泊学等多个学科领域。虽然目前国外对其已有大量及全面的研究,但仍有许多研究处于假设或者未知阶段,需要通过实验进一步验证和解决,如:①现在的研究认为MIB和GSM主要是蓝藻和放线菌代谢产生,但是不是有真核生物或者其他途径也有可能产生这两种物质并没有被报道;②在影响异嗅物质产生的因素中,怎样才能抑制异嗅物质在天然水体中的产生;③MIB和GSM迁移转化过程中,各种生物和物理过程产生的作用和其各所占比例并未见报道。

因此,关于水中异嗅物质MIB和GSM仍然还有许多方面需要研究。包括:①对MIB、GSM和其他异嗅物质来源更加深入和全面地研究;②如何在水中异嗅物质爆发季节做好预防工作,有效减少水中异嗅事件的发生;③比较不同途径处理异嗅物质的效果、速率和成本,以便在水中异嗅物质爆发时,帮助快速处理和控制异嗅物质,减轻异嗅事件对水厂、居民用水的影响。在我国这是一个刚刚发展的研究领域,随着人们对生活要求的提高,异嗅问题将成为研究热点。

[1] Benanou D, Acobas F, De Roubin M R, et al. Analysis of off-flavors in the aquatic environment by stir bar sorptive extraction-thermal desorption-capillary GC/MS/olfactometry[J]. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry, 2003, 376(1): 69-77.

[2] Burlingame GA, Dahme. History oftaste and odor: the Philadelphia story[J]. Proceedings of AWWA Water Quality Technology ConferenceSt. Louis, MO: 1989,13(17):1-12.

[3] 徐盈, 黎雯, 吴文忠,等. 东湖富营养水体中藻菌异嗅性次生代谢产物的研究[J].生态学报, 1999, 19(2):212-216.

[4] 马晓雁, 高乃云, 李青松, 等. 上海市饮用水中痕量土臭素和二甲基异冰片年变化规律及来源研究[J]. 环境科学, 2008, 29(4): 902-908.

[5] 齐飞, 徐冰冰, 樊慧菊, 等. 北京市景观水体嗅味污染特征[J]. 环境科学研究, 2011, 24(10): 1115-1122.

[6] Berthelot M, André G. Sur l’odeur propre de la terre[J]. Comptes rendus, 1891, 112: 598-599.

[7] Gerber N N, Lechevalier H A. GSM, an earthly smelling substance isolated from actinomycetes[J]. Applied Microbiology, 1965, 13(6): 935-938.

[8] Silvey J K, Roach A W. Actinomycetes may cause tastes and odors in water supplies[J]. Public Works, 1956, 87(5): 103-106.

[9] Hoak R D. Origin of tastes and odors in drinking water[J]. Public Works,1957,88:83-85.

[10]Gaines H D, Collins R P. Volatile substances produced by Streptomyces odorifer[J]. Lloydia, 1963, 26(4): 247-253.

[11]Medsker L L,Jenkins D, Thomas J F, et al. Odorous compounds in natural waters. 2-Exo-hydroxy-2-methylbornane, the major odorous compound produced by several actinomycetes[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 1969, 3(5): 476-477.

[12]Safferman R S, Rosen A A, Mashni C I, et al. Earthy-smelling substance from a blue-green alga[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 1967, 1(5): 429-430.

[13]Tabachek J A L, Yurkowski M. Isolation and identification of blue-green algae producing muddy odor metabolites, GSM, and 2-methylisoborneol, in saline lakes in Manitoba[J]. Journal of the Fisheries Board of Canada, 1976, 33(1): 25-35.

[15]Persson P E. Odorous algal cultures in culture collections[J]. Water Science & Technology, 1988, 20(8-9): 211-213.

[16]Yagi O, Sugiura N, Sudo R.Chemical and biological factors on the musty odor occurrence in Lake Kasumigaura Japan[J].Japanese Journal of Limnology,1985,46(1):32-40.

[17]Izaguirre G, Taylor W D. A guide to GSM-and MIBproducing cyanobacteria in the United States[J].Water Science &Technology, 2004,49 (9):19-24.

[18]Watson S B. Chemical communication or chemical waste? A review of the chemical ecology of algal odour[J]. Phycologia, 2003, 42: 333-350.

[19]Juttner F, Hoflacher B,Wurster K.Seasonal analysis of volatile organic biogenic substances (VOBS) in freshwater phytoplankton populations dominated by Dinobryon, Microcystis and Aphanizomenon[J]. Phycology,1986,22(2):169-175.

[20]Jones G J, Korth W. In situ production of volatile odour compounds by river and reservoir phytoplankton populations in Australia[J].Water Science Technology,1995,31(11):145-151.

[21]Sklenar K S, Horne A J.Horizontal distribution of GSM in a reservoir before and after copper treatment[J]. Water Science Technology, 1999,40(40):229-237.

[23]Naes H, Post A F. Transient states of geosmin, pigments, carbohydrates and proteins in continuous cultures of Oscillatoria brevis induced by changes in nitrogen supply[J]. Archives of microbiology, 1988, 150(4): 333-337.

[24]Rosen B H, MacLeod B W, Simpson M R. Accumulation and Release of Geosmin during the Growth Phases of Anabaena circinalis (Kutz.) Rabenhorst[J]. Water Science & Technology, 1992, 25(2): 185-190.

[25]Saadoun I M K, Schrader K K, Blevins W T.Environmental and nutritional factors affecting geosmin synthesis byAnabaenasp.[J]. Water Research, 2001, 35(5): 1209-1218.

[26]Dionigi C P, Ingram D A. Effects of temperature and oxygen concentration on geosmin production byStreptomycestendaeandPenicilliumexpansum[J]. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 1994, 42(1): 143-145.

[27]Dionigi C P, Ahten T S, Wartelle L H. Effects of several metals on spore, biomass, and geosmin production byStreptomycestendaeandPenicilliumexpansum[J]. Journal of industrial microbiology, 1996, 17(2): 84-88.

[28]Schrader K K, Blevins W T. Effects of carbon source, phosphorus concentration, and several micronutrients on biomass and geosmin production byStreptomyceshalstedii[J].Journal of industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2001, 26(4): 241-247.

[29]Sunesson A L, Nilsson C A, Carlson R, et al. Production of volatile metabolites from Streptomyces albidoflavus cultivated on gypsum board and tryptone glucose extract agar-Influence of temperature, oxygen and carbon dioxide levels[J]. The Annals of Occupational Hygiene, 1997, 41(4): 393-413.

[30]Wood S,Williams S T, White W R.Potential sites of GSM production by Streptomycetes in and around reservoirs[J]. The Journal of Applied Bacteriology,1985,58:319-326.

[31]Sugiura N, Inamori Y, Hosaka R,et al.Algae enhancing musty odor production by actinomycetes in Lake Kasumigaura[J].Hydrobiologia,1994,288(1):57-64.

[32]Dionigi C P, Millie D F, Spanier A M, et al. Spore and geosmin production byStreptomycestendaeon several media[J]. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 1992, 40(1): 122-125.

[33]Bentley R, Meganathan R.GSM and methylisoborneol biosynthesis in streptomycetes. Evidence for an isoprenoid pathway and its absence in non-differentiating isolates[J]. FEBS Letters,1981,125(2):220-222.

[34]Cane D E, He X, Kobayashi S. GSM biosynthesis in Streptomyces avermitilis. Molecular cloning, expression, and mechanistic study of the germacradienol/GSM synthase[J]. The Journal of antibiotics, 2006, 59(8): 471-479.

[35]Dionigi C P, Ahten T S, Wartelle L H. Effects of several metals on spore, biomass, and GSM production byStreptomycestendaeandPenicilliumexpansum[J]. Journal of industrial microbiology, 1996, 17(2): 84-88.

[36]Jüttner F, Bogenschütz O. Geranyl derivatives as inhibitors of the carotenogenesis inSynechococcusPCC 6911 (cyanobacteria)[J]. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C, 1983, 38(5-6): 387-392.

[37]Juttner F,Watson S B.Biochemical and ecological control of GSM and 2-methylisoborneol in source waters[J].Applied and Environment Microbiology,2007,73(14):4395-4406.

[38]Spiteller D, Jux J, Boland W,et al. Feeding of [5,4-2H2]-1-desoxy-D-xylulose and [4,4,6,6,6-2H5]-mevalolactone to a GSM-producingStreptomycessp. andFossombroniapusilla[J].Phytochemistry,2002,61:827-834

[39]Rodríguez-Concepción M, Boronat A. Elucidation of the methylerythritol phosphate pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis in bacteria and plastids. A metabolic milestone achieved through genomics[J]. Plant Physiol,2002,130(3):1079-1089.

[40]Kuzuyama T. Mevalonate and nonmevalonate pathways for the biosynthesis of isoprene units[J]. Bioscience Biotechnology Biochemistry,2002,66(8):1619-1627.

[41]Seto H, Watanabe H, Furihata K. Simultaneous operation of the mevalonate and non-mevalonate pathways in the biosynthesis of isopentenly diphosphate inStreptomycesaeriouvifer[J]. Tetrahedron letters, 1996, 37(44): 7979-7982.

[42]Seto H, Orihara N, Furihata K. Studies on the biosynthesis of terpenoids produced by actinomycetes.Part 4. Formation of BE-40644 by the mevalonate and nonmevalonate pathways[J]. Tetrahedron letters,1998,39(51):9497-9500.

[43]Dickschat J S, Bode H B, Mahmud T, et al. A novel type of GSM biosynthesis in myxobacteria[J]. The Journal of organic chemistry, 2005, 70(13): 5174-5182.

[44]Dickschat J S, Nawrath T, Thiel V, et al. Biosynthesis of the Off-Flavor 2-Methylisoborneol by the Myxobacterium Nannocystis exedens[J]. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2007, 46(43): 8287-8290.

[45]Watson S B, Ridal J, Boyer G L. Taste and odour and cyanobacterial toxins: impairment, prediction, and management in the Great Lakes[J]. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 2008,65(8): 1779-1796.

[46]Durrer M, Zimmermann U, Jüttner F. Dissolved and particle-bound GSM in a mesotrophic lake (lake Zürich): spatial and seasonal distribution and the effect of grazers[J]. Water Research, 1999, 33(17): 3628-3636.

[47]戴树桂. 环境化学[M].北京:高等教育出版社,1987:214.

[48]Silvey J K G, Henley A W, Nunez W J, et al. Biological control: control of naturally occurring taste and odors by microorganisms[C].Detroit, USA: Proceedings of the National Biological Congress, 1970.

[49]Ho L,Sawade E,Newcombe G.Biological treatment options for cyanobacteria metabolite removal-A review[J].Water Research,2012,46(5):1536-1548.

[50]Izaguirre G, Wolfe R L, Means E G. Degradation of 2-methylisoborneol by aquatic bacteria[J]. Applied and environmental microbiology, 1988, 54(10): 2424-2431.

[51]Egashira K, Ito K, Yoshiy Y. Removal of musty odor compound in drinking water by biological filter[J]. Water Science & Technology, 1992, 25(2): 307-314.

[52]Tanaka A, Oritani T, Uehara F, et al. Biodegradation of a musty odour component, 2-methylisoborneol[J]. Water Research, 1996, 30(3): 759-761.

[53]Oikawa E, Shimizu A, Ishibashi Y. 2-methylisoborneol degradation by the cam operon from Pseudomonas putida PpG1[J]. Water Science and Technology, 1995, 31(11): 79-86.

[54]Sumitomo H. Odor decomposition by the yeast Candida[J]. Water Science & Technology, 1988, 20(8-9): 157-162.

[55]Ishida H, Miyaji Y. Biodegradation of 2-methylisoborneol by oligotrophic bacterium isolated from a eutrophied lake[J]. Water Science & Technology, 1992, 25(2): 269-276.

[56]Lauderdale C V, Aldrich H C, Lindner A S. Isolation and characterization of a bacterium capable of removing taste-and odor-causing 2-methylisoborneol from water[J]. Water research, 2004, 38(19): 4135-4142.

[57]Yagi M, Nakashima S, Muramoto S. Biological degradation of musty odor compounds, 2-methylisoborneol and geosmin, in a bio-activated carbon filter[J]. Water Science & Technology, 1988, 20(8-9): 255-260.

[58]Narayan L V, Nunez III W J. Biological Control: Isolation and Bacterial Oxidation of the Taste-and-Odor Compound Geosmin [J]. Journal-American Water Works Association, 1974, 66(9): 532-536.

[59]Saadoun I, El-Migdadi F. Degradation of geosmin-like compounds by selected species of Gram-positive bacteria[J]. Letters in applied microbiology, 1998, 26(2): 98-100.

[60]Elhadi S L, Huck P M, Slawson R M. Removal of GSM and 2-methylisoborneol by biological filtration[J]. Water Science& Technology,2004,49(9):273-280.

[61]Elhadi S L N, Huck P M, Slawson R M. Factors affecting the removal of GSM and MIB in drinking water biofilters[J]. Journal of the American Water Works Association,2006,98(8):108-119.

[62]Ho L, Hoefel D, Bock F, et al. Biodegradation rates of 2-methylisoborneol (MIB) and GSM through sand filters and in bioreactors[J]. Chemosphere, 2007,66 (11):2210-2218.

[63]Aoyama K, Kawamura N, Saitoh M,et al. Interactions between bacteria-free Anabaenamacrospora clone and bacteria isolated from unialgal culture[J].Water Science &Technology,1995,31(11):121-126.

[64]Lupton F S, Marshall K C. Specific adhesion of bacteria to heterocysts ofAnabaenaspp. and its ecological significance[J].Applied and Environmental Microbiology,1981,42(6):1085-1092.

[65]Trudgill P W. Microbial degradation of the alicyclic ring. Structural relationships and metabolic pathways [Crude petroleum extraction][J]. Microbiology Series, 1984, 13: 131-180.

[66]Rittmann, B.E., Gantzer, C.J., Montiel, A. Advances in Taste and-Odor Treatment and Control[M]. Denver, USA: Amer Water Works Assn, 1995:209-246.

[67]Saito A, Tokuyama T, Tanaka A, et al. Microbiological degradation of (-)-GSM[J].Water research, 1999,33(13): 3033-3036.

[68]Westerhoff P, Rodriguez-Hernandez M, Larry B, et al.Seasonal occurrence and degradation of 2-methylisoborneol in water supply reservoirs[J].Water Research,2005,39(20):4899-4912.

[69]Lalezary S, Pirbazari M, McGuire M J, et al. Air stripping of taste and odor compounds from water[J]. Journal-American Water Works Association, 1984, 76(3): 83-87.

[71]Zonglai Li, Peter Hobson, Wei An,et al.Earthy odor compounds production and loss in threecyanobacterial cultures[J].Water Research,2012,46(16):5165-5173.

[72]Korategere V, Atasi K, Linden K, et al. Evaluation of Two UV Advanced Oxidation Technologies for the Removal of Organic and Organoleptic Compounds: A Pilot Demonstration[C].USA: AWWA Annual Conference, 2004.

[73]Collivignarelli C, Sorlini S. AOPs with ozone and UV radiation in drinking water: contaminants removal and effects on disinfection byproducts formation[J]. Water Science and Technology, 2004, 49(4): 51-56.

[74]Glaze W H, Schep R, Chauncey W, et al. Evaluating oxidants for the removal of model taste and odor compounds from a municipal water supply[J]. Journal-American Water Works Association, 1990, 82(5): 79-84.

[75]李林, 宋立荣, 陈伟,等. 淡水藻源异嗅化合物的光降解和光催化降解研究[J].中国给水排水,2007,13(23):102-105.

[76]Graham M R, Summers R S, Simpson M R, et al. Modeling equilibrium adsorption of 2-methylisoborneol and geosmin in natural waters[J]. Water Research, 2000, 34(8): 2291-2300.

[77]Whitfield F B. Biological origins of off-flavors in fish and crustacean[J]. Water Science Technology, 1999, 40(6): 265-272.

[78]Clark K E, Gobas F A P C, Mackay D. Model of organic chemical uptake and clearance by fish from food and water[J]. Environmental science & technology, 1990, 24(8): 1203-1213.

[79]Howgate P. Tainting of farmed fish by GSM and 2-methyl-iso-borneol: a review of sensory aspects and of uptake/depuration[J]. Aquaculture, 2004, 234(1): 155-181.

Resource, Migration & Transformation of Two Main Off-Flavor Compounds in Natural Water

LI Chong-wei1, ZOU Pan1, YANG Zhao-guang1, 2, LI Hai-pu1

(1.Schl.ofChem. &Chem.Engin.,ZhongnanUni.,Changsha410083; 2.ShenzhenRes.Inst.ofZhongnanUni.,Shenzhen518057)

In recent years, the issue of taste and odor (T&O) in water attracts people’s attention. Study has found that the main T&O compounds in natural waters were volatile secondary metabolite produced by microbes and algae. In this paper, the resource and biosynthesis of two main off-flavor compounds, 2-methylisoborneol and geosmin (GSM), in natural aqueous matrices were reviewed. In addition, the migration and transformation of these two off-flavor compounds in natural water by means of absorption, volatilization, photolysis, biodegradation were introduced. The transfer pathway of these two compounds into aquatic life was also discussed in this paper.

volatile secondary metabolite; off-flavor compounds; geosmin; 2-methylisoborneol; fate

国家自然科学基金项目(21277175);深圳市战略性新兴产业发展专项资金项目(JCYJ20120618164317119)

李冲炜 男,硕士研究生。主要从事水体异嗅物质的汇源及控制方面研究。E-mail:132311085@csu.edu.cn

* 通讯作者。女,教授,博士生导师。研究方向为饮用水安全。Tel:0731-88876961,E-mail:lihaipu@csu.edu.cn

2015-11-12;

2015-12-28

Q939.9; X-1

A

1005-7021(2016)02-0074-07

10.3969/j.issn.1005-7021.2016.02.013