空间参照框架的产生机制及与认知机能的关系*

李英武 于 宙 韩 笑

(中国人民大学心理学系, 北京 100872)

在日常生活中, 意识清醒的个体时时刻刻需要组织空间信息, 表征物体的空间方位。个体表征空间方位的方式, 称为空间参照框架(Freksa,Habel, & Wender, 1998)。O’Keefe和Nadel (1978)认为, 可以根据参照物的不同, 将个体表征空间方位的方式分为两种:自我中心参照框架(Egocentric Reference Frame)和环境中心参照框架(Allocentric Reference Frame)。自我中心参照框架的参照物是自身, 基于自身与物体的相对位置编码物体的空间方位。当自身位置改变时, 物体的方位信息随之改变。但自我中心参照框架提供的物体方位信息并不稳定, 当个体移动时, 需要重新表征物体的空间方位信息(Simonnet, Vieilledent, & Tisseau,2013)。环境中心参照框架的参照物是太阳和地球经纬线, 或某一地表特征(如, 山, 峡谷, 海岸线等), 基于环境与物体的关系编码物体的空间方位(Nunez & Cornejo, 2012)。当个体移动时, 环境中心参照框架提供了稳定的空间方位信息(Jiang &Swallow, 2013)。因此, 当自身位置发生变化, 物体的方位信息并不会改变。

1 空间参照框架的产生原因

研究证实, 尽管空间参照框架的认知机能相同(Chan, Baumann, Bellgrove, & Mattingley, 2013a),任一空间参照框架均可正确清晰地表征物体空间方位(Simonnet et al., 2013)。但个体在表征空间方位信息时, 偏好不同的参考框架。

一方水土养一方人, 其中自然地理环境是产生偏好的重要因素。处于不同的自然地理环境下,会发展出不同的空间术语, 进而影响个体对物体空间方位的表征和表达(Levinson, 1997; 张积家等, 2007)。如, 我国南方人偏好自我中心的参照框架, 而北方人则偏好环境中心的参照框架(张积家,刘丽虹, 2007)。日出东方, 日落西方, 正午太阳位于南方。中国南方地区多阴雨, 少见太阳, 难以采用环境中心参照框架表征物体位置。北方多晴天,易于采用环境中心参照框架。

空阔环境中个体偏好环境中心参照框架, 狭小环境中个体偏好自我中心参照框架(Istomin &Dwyer, 2009)。在环境信息刺激下, 个体两种空间参照框架会同时激活, 再基于环境特征, 例如,房间几何形状(张积家, 刘丽虹, 石艳彩, 2008;Kelly & McNamara, 2008)等信息, 选用某一空间参照框架, 抑制另一空间参照框架(Carlson & Van Deman, 2008)。南方多丘陵, 山地, 地势崎岖不平,个体长期生活在山间狭小的平地上, 生活空间相对狭小。北方多平原、高原, 个体生活环境宽敞,视野开阔。个体生活在一定环境中, 容易激活相应的空间参照框架(Greenauer, Mello, Kelly, &Avraamides, 2013)。

在有显著坐标轴的环境中, 更易采用环境中心参照框架, 相反则采用自我中心参照框架(Mou,2004)。显著坐标轴指的是环境的几何结构, 例如,房间的几何形状(特别是矩形)或突出的地标。行为学认为可以用“对齐效应(alignment effect)”进行解释(Kelly & McNamara, 2008), 不论是在动态还是静态的空间认知任务中都出现了“对齐效应” (Chan,Baumann, Bellgrove, & Mattingley, 2013b), 采用虚拟现实技术的研究也验证了类似结论(Kelly,Sjolund, & Sturz, 2013)。神经生理学的研究也从侧面证实了此观点。在与突出坐标轴的对齐的空间任务中, 激活了腹侧视觉通路(环境中心参照框架的生理基础), 在未与突出坐标轴对齐的空间任务中, 激活了背侧视觉通路(自我中心参照框架的生理基础) (Chan et al., 2013a)。当场景中有逼真的背景时, 个体更容易激活自我中心参照框架(Johannsen & De Ruiter, 2013)。

2 空间参照框架的发展过程

从经典的儿童空间学习理论(Theory of Spatial Learning)视角来看, 个体对空间的表征是从自我中心表征发展到环境中心表征, 从基本粗糙的空间表征发展到先进复杂的空间表征(Piaget &Inhelder, 1997), 环境中心表征是在自我中心表征的基础上发展起来的(Hazen, 1978)。该理论认为,新生儿自身位置相对固定, 与环境的互动较少,加之处理自我中心空间方位信息的神经机制位于较低级的皮层。人类大脑不同结构成熟的时间不同, 对13名健康儿童8至10年的纵向追踪发现, 低级皮层成熟先于高级皮层, 皮层成熟是认知机能成熟的先决条件(Gogtay et al., 2004)。因此, 新生儿倾向于采用自我中心参照框架来表征位置信息。

同时, 运动会促进相关皮层的成熟(Portugal et al., 2013)。前庭和动觉系统输入的信息, 对促进环境中心参照框架相关皮层的成熟至关重要。爬行标志着婴儿空间认知能力质的飞跃, 爬行有助于儿童确定他们在环境中的位置(Thelen & Smith,1996)。对3~6岁儿童空间参照框架发展情况的研究发现, 3岁的儿童已不单纯采用自我空间参照框架, 表现出了成人空间认知能力的全部核心成分,开始采用环境中心参照框架(Nardini, Burgess,Breckenridge, & Atkinson, 2006)。对6~10岁儿童研究发现, 10岁儿童可以在小规模环境中灵活地整合和切换两类参照框架, 环境中心参照框架发育成熟(Moraleda, Broglio, Rodríguez, & Gómez, 2013)。

然而, 随着研究技术的进步, 大量理论和实证证据支持两个空间参照框架的生理机制和习得过程是同时的(Ishikawa & Montello, 2006; Mou et al., 2004; Zaehle et al., 2007)。与自我中心参照框架生理机制的成熟时间类似, 环境中心参照框架的生理基础—海马, 在人类15个月时已经完全成熟(Kretschmann, 1986), 具备采用两类参照框架的生理基础。Ishikawa和Montello (2006)采用纵向研究反驳了Siegel和White (1975)提出的空间表征发展的阶段理论, 认为个体两个空间参照框架的习得过程是同时发生的。采用虚拟现实技术,在学习阶段允许被试自发采用自己偏好的参照框架编码空间信息, 在测试阶段, 测验被试在两类参照框架间转换的速度和精确度。结果发现, 被试可以即时切换到非偏好的空间参照框架, 证明两类空间参照框架的信息是同时习得的(Igloi,Zaoui, Berthoz, & Rondi-Reig, 2009)。同时, 环境中心参照框架只是空间框架的一种具体形式, 并不需要耗费大量认知资源, 也不需要基于自我中心参照框架提供的空间信息(Moraleda et al., 2013)。

两个参照框架同时并存, 个体在表征他人行为时, 也是同时采用两个参照框架(Wiggett, Downing,& Tipper, 2013)。先是基于环境特征, 例如, 房间几何形状(Kelly & McNamara, 2008)等信息, 选用某一空间参照框架, 再抑制另一空间参照框架(Carlson & Van Deman, 2008)。Gramann等(2005)采用虚拟现实技术, 指导被试相继采用偏好参照框架和非偏好参照框架, 研究发现, 两种条件下被试反应的精确度几乎一致, 证明了两类空间参照框架同时并存。

基于以上研究, Gramann (2013)等提出空间参照框架形成的三个步骤:大脑中同时存在两种空间参照框架的生理基础; 特定的刺激会激活某一空间参照框架的神经回路; 长期对某一空间参照框架的持续激活可以形成对该空间参照框架的偏好。

空间参照框架的发展持续终身。在同类环境中生活的时间越久, 与此类环境的互动越多, 个体对相应空间参照框架偏好度越强。但这并不意味着个体不会采用另一空间参照框架。虽然, 个体对某一空间参照框架存在偏好, 并伴随生理机制改变(Chan et al., 2013a), 但这类改变是可逆的。现代社会人员流动频繁, 社会文化和地理环境可能发生改变, 个体先前偏好的空间参照框架,可能不适用于新环境。现有的空间参照框架会同化新的空间记忆, 新空间参照框架可以重组现有的空间记忆(Greenauer et al., 2013; Kelly &McNamara, 2010)。个体逐渐形成了对另一类空间参照框架的偏好。

3 空间参照框架的生理机制

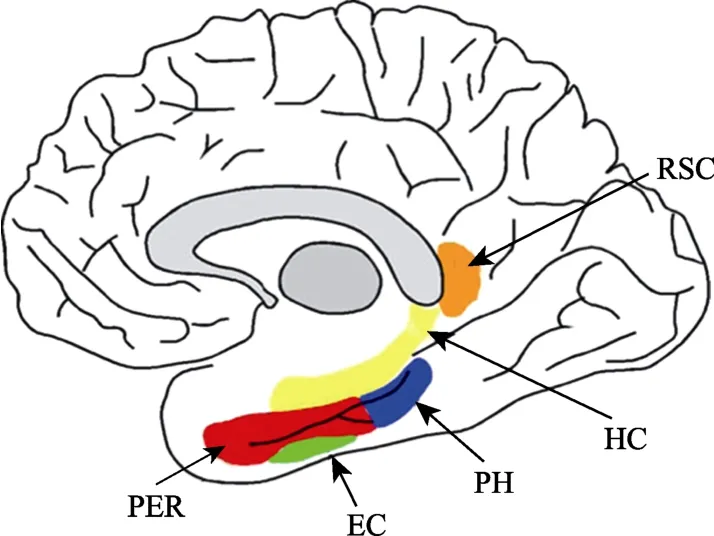

啮齿动物海马中位置细胞的发现开启了对不同空间参照框架生理机制的研究(O'Keefe &Nadel, 1978)。随着脑成像等研究技术的进步, 对生理机制的研究越来越明确。最常用的脑成像技术是功能性磁共振成像(fMRI), 通过测量局部脑血流量的变化以确定该脑区的激活度(Matthews& Jezzard, 2004)。研究发现涉及空间认知的主要脑区(见图1), 包括:内侧颞叶, 特别是海马、海马旁回等, 其中包括旁海马皮质、内嗅皮层和边缘皮层(Chrastil, 2013)。内侧颞叶包括部分涉及空间学习、空间记忆的脑区(Lech & Suchan, 2013),海马旁回不同于旁海马皮质, 海马旁回范围更为广泛。除了内侧颞叶和顶叶, 空间认知也涉及压后皮质(位于扣带皮层附近) (Wolbers & Buchel,2005)。尾状核也在空间认知中发挥重要作用(Bohbot, Gupta, Banner, & Dahmani, 2011)。内侧颞叶中的特定神经细胞也与空间认知有关, 包括:位置细胞、头向细胞、网格细胞。海马中的位置细胞和内嗅皮层中的网格细胞参与个体对空间方位的动态表征空间, 同时在空间记忆的存储中起至关重要的作用(Whitlock, Sutherland, Witter,Moser, & Moser, 2008)。大量脑成像研究发现, 人类在虚拟现实中的空间认知任务会激活从颞叶到顶叶再到额叶的复杂神经网络(Chrastil, 2013;Nemmi, Boccia, Piccardi, Galati, & Guariglia, 2013;Wolbers & Buchel, 2005; Zaehle et al., 2007)。Nemmi (2013)等采用fMRI技术运用柯西块敲击测验(the Corsi block tapping test, CBT)和柯西行走测验(the walking Corsi test, WalCT)研究发现,两类任务均激活了由海马, 海马旁回, 尾状核,顶叶和压后皮质, 以及右侧舌回, 距状沟, 背外侧前额叶皮层等区域组成的神经网络。

图1 空间认知的主要脑区

3.1 环境中心参照框架的生理机制

对采用不同空间参照框架的空间认知任务的研究发现, 采用环境中心参照框架会激活海马,杏仁核, 海马旁回, 边缘皮层, 内嗅皮层, 眶额叶皮层等部位(Banner, Bhat, Etchamendy, Joober, &Bohbot, 2011; Bohbot, Lerch, Thorndycraft, Iaria,& Zijdenbos, 2007; Chrastil, 2013; Zaehle et al.,2007)。环境中心参照框架的生理机制还包括海马中的位置细胞和内嗅皮层中的网格细胞, 以及头向细胞(Hafting, Fyhn, Molden, Moser, & Moser,2005; Moser & Moser, 2008; Taube, Wang, Kim, &Frohardt, 2013), 位置细胞和网格细胞储存环境中心编码的空间信息(Doeller, Barry, & Burgess,2010)。采用fMRI对自发偏好环境中心参照框架的个体研究发现, 该类个体海马及其附近脑区的灰质体积更大, 密度更高, 在完成空间任务时, 海马的激活程度更高(Bohbot et al., 2007)。Etchamendy和Bohbot (2007)的实验发现, 自发采用环境中心参照框架的个体, 在完成虚拟迷宫任务时, 海马显著激活。不仅自发采用环境中心参照框架个体的海马显著激活, 指导被试采用环境中心参照框架个体的海马激活程度也增加。Iaria (2003)等采用虚拟现实技术, 指导被试采用环境中心参照框架解决空间任务, 练习一段时间后, 发现被试海马激活增加。随机要求被试采用不同空间参照框架, 通过fMRI记录的大脑激活情况也证明了以上结论(Wilson, Woldorff, & Mangun, 2005)。

环境中心表征是基于环境中心参照框架表征空间信息的方式(Mou et al., 2004)。对脑损个体的研究也与对健康个体的研究保持一致, 个体出现环境中心定向障碍与海马旁回的损伤有关(Takahashi & Kawamura, 2002)。对半侧空间忽视病人的研究发现, 环境中心表征的空间信息加工涉及腹侧通路(Medina et al., 2009), 威廉姆斯综合症患者的腹侧通路的损伤导致了环境中心参照框架的缺陷(Bernardino, Mouga, Castelo-Branco,& van Asselen, 2013)。

3.2 自我中心参照框架的生理机制

采用自我中心参照框架会激活杏仁核, 后顶叶皮层, 尾状核等区域(Banner et al., 2011; Bohbot et al., 2011; Etchamendy & Bohbot, 2007; Whitlock et al., 2008; Wolbers, Wiener, Mallot, & Buchel,2007)。采用fMRI对自发偏好自我中心参照框架的个体研究发现, 该类个体尾状核及其附近脑区的灰质体积更大, 密度更高, 在完成空间任务时,尾状核的激活程度更高(Bohbot et al., 2007)。Etchamendy和Bohbot (2007)采用fMRI技术发现,自发采用环境中心参照框架的个体, 在完成虚拟迷宫任务时, 尾状核显著激活。不仅自发采用自我中心参照框架个体的尾状核显著激活, 指导被试采用自我中心参照框架个体的尾状核激活程度也增加。Iaria (2003)等采用虚拟现实技术, 指导被试采用自我中心参照框架解决空间任务, 练习一段时间后, 发现被试尾状核激活增加。Wilson(2005)等随机要求被试采用不同空间参照框架,通过fMRI记录的大脑激活情况也证明了以上结论。

自我中心表征是基于自我中心参照框架表征空间信息的方式(Mou et al., 2004)对脑损个体的研究也与对健康个体的研究保持一致, 对半侧空间忽视病人的研究发现, 自我中心表征的空间信息加工涉及背侧通路, 包括右侧缘上回(Medina et al., 2009), 威廉姆斯综合症患者背侧通路损伤导致自我中心表征的缺陷也证明了这一点(Bernardino et al., 2013)。

3.3 整合两类参照框架信息的生理机制

后顶叶皮层, 顶—枕联合区和压后皮质整合来自不同空间参照框架的信息(Chen, Weidner,Weiss, Marshall, & Fink, 2012; Whitlock et al.,2008)。Iaria (2003)等采用虚拟现实技术, 指导一组被试采用环境中心参照框架完成空间任务, 另一组被试采用自我中心参照框架完成空间任务,发现两组被试的后顶叶皮层均激活。后顶叶皮层损伤的个体, 难以整合两类参照框架的信息, 从而损害空间定向能力, 以致空间认知能力, 功能损害的程度取决于损伤的体积大小(Seubert,Humphreys, Mueller, & Gramann, 2008)。Zaehle等(2007)运用语言诱发被试采用不同空间参照框架,发现分别采用不同空间参照框架时, 顶—枕联合区均激活。对两类空间参照框架信息的编码和提取需要整合两类空间参照框架的信息, 在此过程中, 激活了后顶叶皮层和压后皮质(Byrne, Becker,& Burgess, 2007)。Gramann等 (2010)采用EEG记录个体完成空间任务时的脑电, 在整合两类空间参照框架的信息时, 压后皮质的激活程度更高。用脑电技术的研究结果也与采用fMRI的研究结果一致。

4 空间参照框架的认知机能

4.1 空间参照框架与注意

空间参照框架影响注意的空间分布。研究发现, 注意过程会采用不同空间参照框架(Mathot &Theeuwes, 2010; Pertzov, Avidan, & Zohary, 2011)。两类空间参照框架在注意过程中均非常重要, 某些情况下, 二者是共存的(Golomb, Nguyen-Phuc,Mazer, McCarthy, & Chun, 2010; Mathot & Theeuwes,2010; Pertzov et al., 2011)。在短时注意中, 基于任务(动手反应或动眼反应)和注意任务类型(瞬时注意或持续性注意)决定选用哪一空间参照框架(Chun, Golomb, & Turk-Browne, 2011; Golomb,Chun, & Mazer, 2008; Golomb et al., 2010)。

不同的注意控制过程采用不同的空间参照框架(Eimer, Forster, & Van Velzen, 2003)。前注意(anterior attention)控制过程是基于环境中心参照框架, 后注意(posterior attention)控制过程主要是基于自我中心参照框架(Eimer et al., 2003)。偶然习得注意(incidentally learned attention)不同于传统注意, 它反映稳定的环境特性, 并且不易消退。偶然习得空间注意中, 个体偏好选用自我中心参照框架(Jiang & Swallow, 2013; Jiang, Swallow, &Sun, 2014)。被试以前无意识的学习经验, 会影响到被试的空间注意分配(Chalk, Seitz, & Series,2010; Umemoto, Scolari, Vogel, & Awh, 2010)。

4.2 空间参照框架与定向

空间参照框架作为表征物体空间方位的工具,另一重要机能是定向。不同的定向策略是不同空间参照框架的机能表现。一般来说, 定向策略分为两类——“空间策略(spatial strategy)”和“响应策略(response strategy)”。这两种定向策略无所谓好坏, 只有更适用于当前情境的策略。“空间策略”基于环境中心参照框架, 依据地标来定向, 研究证实了海马在空间策略中起关键作用(Deshmukh& Knierim, 2012; Pilly & Grossberg, 2012)。“响应策略”基于自我中心参照框架, 按照身体运动序列定向, 例如, 从起点先向左转再直走。响应策略显著激活纹状体, 特别是尾状核(Chrastil, 2013;Zaehle et al., 2007)。不同定向策略的生理机制与相应空间参照框架的生理机制一致。

有研究指出, 定向的性别差异只存在于地标缺失的环境中, 在多个地标的环境中无性别差异(Andersen, Dahmani, Konishi, & Bohbot, 2012)。随时间推移, 女性对地标的关注度一直较高, 男性对地标关注度下降(Andersen et al., 2012)。男性女性在具体定向策略上存在性别差异, 在环境中存在多种环境信息时, 男性偏好综合各类信息进行定向而女性则偏好选用地标信息, 使用采用“空间策略”进行定向(Picucci, Caffo, & Bosco, 2011;Rosenthal, Norman, Smith, & McGregor, 2012)。

4.3 空间参照框架与记忆

完成空间任务必然涉及空间记忆能力。海马是空间学习和记忆的关键脑区(Pilly & Grossberg,2012), 是形成认知地图的核心(Deshmukh &Knierim, 2012), 海马损伤会导致空间记忆缺陷。大鼠(Kesner & Goodrich-Hunsaker, 2010; Ramos,2008), 猴子(Bachevalier, Wright, & Katz, 2013)的海马损伤导致了严重的空间学习和记忆缺陷。对海马损伤病人的研究也验证了以上研究结果(Hirni, Kivisaari, Monsch, & Taylor, 2013; Milton,Butler, Benattayallah, & Zeman, 2012)。

偏好不同空间参照框架会改变相应神经结构的形态与机能。偏好环境中心参照框架会增加海马及其附近脑区的灰质(Chan et al., 2013a), 偏好自我中心参照框架会增加尾状核的灰质(Bohbot et al., 2007)。海马灰质体积增大会增强正常人的空间记忆能力(Biegler, McGregor, Krebs, & Healy,2001; Hartley & Harlow, 2012)。激活不同的空间参照框架, 会影响海马中N-乙酰天冬氨酸(NNA)的浓度(Loevden et al., 2011), 改变相应神经结构的机能。海马中NNA是神经元和神经胶质细胞机能的指标。

空间参照框架研究成果的应用已经扩展到老年心理学领域。大量研究证实, 随着个体老龄化,海马体积减小, 激活程度降低, 使得老年个体的认知能力降低, 患老年痴呆症的风险增加(O'Brien et al., 2010)。研究发现, 持续激活环境中心参照框架的老年人会增加海马灰质体积, 降低患老年痴呆的风险(Konishi & Bohbot, 2013)。日常偏好采用环境中心参照框架的老人, 相对于采用自我中心参照框架的老年, 其海马体积更大, 患老年痴呆症的风险更低。

5 未来研究展望

研究发现, 狭小的环境中, 个体偏好自我中心参照框架, 空阔的环境中, 个体偏好环境中心参照框架(Gramann, 2013; Istomin & Dwyer,2009)。偏好不同空间参照框架会引起生理机制和机能的改变, 偏好环境中心参照框架, 会增加海马灰质的体积(Chan et al., 2013a), 增强海马的机能(Loevden et al., 2011)。在现代城市生活中, 城市儿童从小生活在“水泥森林”中, 生活空间相对狭小, 农村儿童生活在环境空阔的郊区。根据前人研究, 可假设城市儿童偏好自我中心参照框架,农村儿童偏好环境中心参照框架。进一步假设,由于偏好不同空间参照框架, 城市与农村儿童在记忆, 情绪等其他涉及海马的认知功能中有差异。这些假设是否真实成立, 尚需进一步研究。

大多数采用脑成像技术对完成空间任务时脑区激活情况的研究要求被试或坐或躺, 保持不动,以避免运动造成干扰(Makeig, Gramann, Jung,Sejnowski, & Poizner, 2009)。在日常生活中, 空间任务很大程度上依赖前庭觉和本体觉(Taube,Valerio, & Yoder, 2013)。研究中要求被试保持不动,切断了重要的信息源。在保持实验严谨性, 降低误差的同时, 也降低了研究的生态效度。未来需要开发新研究技术和方法, 完全再现个体在现实生活中完成的空间任务的情景, 动态记录个体完成实际空间任务时各项生理变化。

当前对尾状核机能的研究及应用远远不足。偏好自我中心参照框架增加尾状核灰质体积, 这一结论尚未得到广泛应用。尾状核与依恋行为有关, 同时涉及身体运动的速度和精确性(Villablanca, 2010), 但是, 目前针对尾状核涉及心理过程的研究仍有欠缺。未来需要关注尾状核灰质的增加, 是否会影响涉及尾状核的心理过程的改善与治疗, 例如, 强迫症(男性强迫症患者的右侧尾状核体积显著增大) (Narayanaswamy, Jose,Kalmady, Venkatasubramanian, & Reddy, 2013), 先天性中枢性低通气综合症(尾状核体积减小)(Kumar et al., 2009)的治疗。海马与尾状核的关系是竞争性交互, 尾状核和海马的灰质体积呈负相关, 偏好不同参照框架, 会造成相应参照框架涉及区域灰质体积的增加, 同时另一参照框架涉及区域的灰质体积减少(Bohbot et al., 2007)。基于前人研究可以假设指导男性强迫症患者偏好环境中心参照框架, 减小尾状核灰质体积, 减轻强迫症症状; 指导先天性中枢性低通气综合征患者偏好自我中心参照框架, 增加尾状核的体积, 减缓病症。这可以成为未来研究的一个突破点。

对不同空间参照框架研究成果的应用已经扩展到老年心理学领域, 采用环境中心参照框架会增加海马灰质的体积, 改善海马的机能。这一结论的应用可以减缓老年人认知衰退, 降低患老年痴呆症的风险。这一结论是否可以应用于认知障碍儿童或成年人?能否将这一结论应用于其他涉及海马的心理过程的改善与治疗, 例如情绪障碍等, 都是值得研究的问题。

邓碧琳, 陈穗清, 张积家, 芦松敏. (2012). 智障儿童空间参考框架的选择.心理与行为研究, 10(1), 44–49.

刘丽虹, 张积家, 王惠萍. (2005). 习惯的空间术语对空间认知的影响.心理学报, 37(04), 469–475.

谢书书, 张积家. (2009). 习惯的空间术语对纳西族和汉族大学生空间参考框架的影响.心理科学, 32(2), 331–333.

张积家, 刘丽虹. (2007). 习惯空间术语对空间认知的影响再探.心理科学, 30(2), 359–361.

张积家, 刘丽虹, 石艳彩. (2008). 情境和任务对空间认知参考框架选择的影响.心理学探新, 28(1), 49–54.

Andersen, N. E., Dahmani, L., Konishi, K., & Bohbot, V. D.(2012). Eye tracking, strategies, and sex differences in virtual navigation.Neurobiology of Learning and Memory,97(1), 81–89.

Athanasopoulos, P., & Bylund, E. (2013). Does grammatical aspect affect motion event cognition? A cross-linguistic comparison of english and swedish speakers.Cognitive Science, 37, 286–309.

Bachevalier, J., Wright, A. A., & Katz, J. S. (2013). Serial position functions following selective hippocampal lesions in monkeys: Effects of delays and interference.Behavioural Processes, 93, 155–166.

Banner, H., Bhat, V., Etchamendy, N., Joober, R., & Bohbot,V. D. (2011). The brain-derived neurotrophic factor val66met polymorphism is associated with reduced functional magnetic resonance imaging activity in the hippocampus and increased use of caudate nucleus-dependent strategies in a human virtual navigation task.European Journal of Neuroscience, 33, 968–977.

Bernardino, I., Mouga, S., Castelo-Branco, M., & Van Asselen, M. (2013). Egocentric and allocentric spatial representations in williams syndrome.Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 19, 54–62.

Biegler, R., McGregor, A., Krebs, J. R., & Healy, S. D.(2001). A larger hippocampus is associated with longerlasting spatial memory.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 98, 6941–6944.

Bohbot, V. D., Gupta, M., Banner, H., & Dahmani, L. (2011).Caudate nucleus-dependent response strategies in a virtual navigation task are associated with lower basal cortisol and impaired episodic memory.Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 96, 173–180.

Bohbot, V. D., Lerch, J., Thorndycraft, B., Iaria, G., &Zijdenbos, A. P. (2007). Gray matter differences correlate with spontaneous strategies in a human virtual navigation task.Journal of Neuroscience, 27, 10078–10083.

Byrne, P., Becker, S., & Burgess, N. (2007). Remembering the past and imagining the future: A neural model of spatial memory and imagery.Psychological Review, 114,340–375.

Carlson, L. A., & Van Deman, S. R. (2008). Inhibition within a reference frame during the interpretation of spatial language.Cognition, 106(1), 384–407.

Chalk, M., Seitz, A. R., & Series, P. (2010). Rapidly learned stimulus expectations alter perception of motion.Journalof Vision, 10(8), 2.

Chan, E., Baumann, O., Bellgrove, M. A., & Mattingley, J. B.(2013a). Extrinsic reference frames modify the neural substrates of object-location representations.Neuropsychologia,51(5), 781–788.

Chan, E., Baumann, O., Bellgrove, M. A., & Mattingley, J. B.(2013b). Reference frames in allocentric representations are invariant across static and active encoding.Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 565.

Chen, Q., Weidner, R., Weiss, P. H., Marshall, J. C., & Fink,G. R. (2012). Neural interaction between spatial domain and spatial reference frame in parietal-occipital junction.Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 24(11), 2223–2236.

Chrastil, E. R. (2013). Neural evidence supports a novel framework for spatial navigation.Psychonomic Bulletin &Review, 20(2), 208–227.

Chun, M. M., Golomb, J. D., & Turk-Browne, N. B. (2011).A taxonomy of external and internal attention.Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 73–101.

Deshmukh, S. S., & Knierim, J. J. (2012). Hippocampus.Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-Cognitive Science, 3(2),231–251.

Doeller, C. F., Barry, C., & Burgess, N. (2010). Evidence for grid cells in a human memory network.Nature, 463(7281),657–687.

Eimer, M., Forster, B., & Van Velzen, J. (2003). Anterior and posterior attentional control systems use different spatial reference frames: Erp evidence from covert tactile-spatial orienting.Psychophysiology, 40(6), 924–933.

Etchamendy, N., & Bohbot, V. D. (2007). Spontaneous navigational strategies and performance in the virtual town.Hippocampus, 17(8), 595–599.

Freksa, C., Habel, C., & Wender, K. F. (1998). Spatial cognition: An interdisciplinary approach to representing and processing spatial knowledge. Allocentric and egocentric spatial representations:Definitions, distinctions, and interconnections(Vol. 1). London: Springer.

Gentner, D., Ozyurek, A., Guercanli, O., & Goldin-Meadow,S. (2013). Spatial language facilitates spatial cognition:Evidence from children who lack language input.Cognition, 127(3), 318–330.

Gogtay, N., Giedd, J. N., Lusk, L., Hayashi, K. M.,Greenstein, D., Vaituzis, A. C., & Thompson, P. M. (2004).Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(21), 8174–8179.

Golomb, J. D., Chun, M. M., & Mazer, J. A. (2008). The native coordinate system of spatial attention is retinotopic.Journal of Neuroscience, 28(42), 10654–10662.

Golomb, J. D., Nguyen-Phuc, A. Y., Mazer, J. A., McCarthy,G., & Chun, M. M. (2010). Attentional facilitation throughout human visual cortex lingers in retinotopic coordinates after eye movements.Journal of Neuroscience, 30(31),10493–10506.

Gramann, K. (2013). Embodiment of spatial reference frames and individual differences in reference frame proclivity.Spatial Cognition and Computation, 13(1), 1–25.

Gramann, K., Muller, H. J., Eick, E. M., & Schonebeck, B.(2005). Evidence of separable spatial representations in a virtual navigation task.Journal of Experimental Psychology-Human Perception and Performance, 31(6), 1199–1223.

Gramann, K., Onton, J., Riccobon, D., Mueller, H. J.,Bardins, S., & Makeig, S. (2010). Human brain dynamics accompanying use of egocentric and allocentric reference frames during navigation.Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience,22(12), 2836–2849.

Greenauer, N., Mello, C., Kelly, J. W., & Avraamides, M. N.(2013). Integrating spatial information across experiences.Psychological Research-Psychologische Forschung, 77(5),540–554.

Grimsen, C., Hildebrandt, H., & Fahle, M. (2008).Dissociation of egocentric and allocentric coding of space in visual search after right middle cerebral artery stroke.Neuropsychologia, 46(3), 902–914.

Hafting, T., Fyhn, M., Molden, S., Moser, M. B., & Moser, E.I. (2005). Microstructure of a spatial map in the entorhinal cortex.Nature, 436(7052), 801–806.

Hartley, T., & Harlow, R. (2012). An association between human hippocampal volume and topographical memory in healthy young adults.Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6,338.

Hazen, N. L., Lockman, J. J., & Pick, H. L. (1978). The development of children's representations of large-scale environments.Child Development, 49(3), 623–636.

Hirni, D. I., Kivisaari, S. L., Monsch, A. U., & Taylor, K. I.(2013). Distinct neuroanatomical bases of episodic and semantic memory performance in alzheimer's disease.Neuropsychologia, 51(5), 930–937.

Iaria, G., Petrides, M., Dagher, A., Pike, B., & Bohbot, V. D.(2003). Cognitive strategies dependent on the hippocampus and caudate nucleus in human navigation: Variability and change with practice.Journal of Neuroscience, 23(13),5945–5952.

Igloi, K., Zaoui, M., Berthoz, A., & Rondi-Reig, L. (2009).Sequential egocentric strategy is acquired as early as allocentric strategy: Parallel acquisition of these two navigation strategies.Hippocampus, 19(12), 1199–1211.

Ishikawa, T., & Montello, D. R. (2006). Spatial knowledge acquisition from direct experience in the environment:Individual differences in the development of metric knowledge and the integration of separately learned places.Cognitive Psychology, 52(2), 93–129.

Istomin, K. V., & Dwyer, M. J. (2009). Finding the way a critical discussion of anthropological theories of human spatial orientation with reference to reindeer herders of northeastern europe and western siberia.Current Anthropology,50(1), 29–49.

Jiang, Y. V., & Swallow, K. M. (2013). Spatial reference frame of incidentally learned attention.Cognition, 126(3),378–390.

Jiang, Y. V., Swallow, K. M., & Sun, L. (2014). Egocentric coding of space for incidentally learned attention: Effects of scene context and task instructions.Journal of Experimental Psychology-Learning Memory and Cognition,40(1), 233–250.

Johannsen, K., & De Ruiter, J. P. (2013). The role of scene type and priming in the processing and selection of a spatial frame of reference.Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 182.

Kelly, J. W., & McNamara, T. P. (2008). Spatial memories of virtual environments: How egocentric experience, intrinsic structure, and extrinsic structure interact.Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 15(2), 322–327.

Kelly, J. W., & McNamara, T. P. (2010). Reference frames during the acquisition and development of spatial memories.Cognition, 116(3), 409–420.

Kelly, J. W., Sjolund, L. A., & Sturz, B. R. (2013).Geometric cues, reference frames, and the equivalence of experienced-aligned and novel-aligned views in human spatial memory.Cognition, 126(3), 459–474.

Kesner, R. P., & Goodrich-Hunsaker, N. J. (2010).Developing an animal model of human amnesia: The role of the hippocampus.Neuropsychologia, 48(8), 2290–2302.

Konishi, K., & Bohbot, V. D. (2013). Spatial navigational strategies correlate with gray matter in the hippocampus of healthy older adults tested in a virtual maze.Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 5, 1.

Kretschmann, H. J. (1986).Brain growth. Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers.

Kumar, R., Ahdout, R., Macey, P. M., Woo, M. A.,Avedissian, C., Thompson, P. M., & Harper, R. M. (2009).Reduced caudate nuclei volumes in patients with congenital central hypoventilation syndrome.Neuroscience,163(4), 1373–1379.

Lech, R. K., & Suchan, B. (2013). The medial temporal lobe:Memory and beyond.Behavioural Brain Research, 254,45–49.

Levinson, S. C. (1997). Language and cognition: The cognitive consequences of spatial description in guugu yimithirr.Journal of Linguistic Anthropolopy, 7(1), 98–131.

Lin, C. T., Huang, T. Y., Lin, W. J., Chang, S. Y., Lin, Y. H.,Ko, L. W., & Chang, E. C. (2012). Gender differences in wayfinding in virtual environments with global or local landmarks.Journal of Environmental Psychology, 32(2),89–96.

Loevden, M., Schaefer, S., Noack, H., Kanowski, M., Kaufmann,J., Tempelmann, C., & Baeckman, L. (2011). Performancerelated increases in hippocampal n-acetylaspartate (naa)induced by spatial navigation training are restricted to bdnf val homozygotes.Cerebral Cortex, 21(6), 1435–1442.

Makeig, S., Gramann, K., Jung, T.-P., Sejnowski, T. J., &Poizner, H. (2009). Linking brain, mind and behavior.International Journal of Psychophysiology, 73(2), 95–100.

Mathot, S., & Theeuwes, J. (2010). Gradual remapping results in early retinotopic and late spatiotopic inhibition of return.Psychological Science, 21(12), 1793–1798.

Matthews, P. M., & Jezzard, P. (2004). Functional magnetic resonance imaging.Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery &Psychiatry, 75(1), 6–12.

Medina, J., Kannan, V., Pawlak, M. A., Kleinman, J. T.,Newhart, M., Davis, C., & Hillis, A. E. (2009). Neural substrates of visuospatial processing in distinct reference frames: Evidence from unilateral spatial neglect.Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 21(11), 2073–2084.

Milton, F., Butler, C. R., Benattayallah, A., & Zeman, A. Z. J.(2012). The neural basis of autobiographical memory deficits in transient epileptic amnesia.Neuropsychologia,50(14), 3528–3541.

Moraleda, E., Broglio, C., Rodríguez, F., & Gómez, A.(2013). Development of different spatial frames of reference for orientation in small-scale environments.Psicothema,25(4), 468–475.

Moser, E. I., & Moser, M. B. (2008). A metric for space.Hippocampus, 18(12), 1142–1156.

Mou, W. M., McNamara, T. P., Valiquette, C. M., & Rump, B.(2004). Allocentric and egocentric updating of spatial memories.Journal of Experimental Psychology-Learning Memory and Cognition, 30(1), 142–157.

Narayanaswamy, J. C., Jose, D. A., Kalmady, S. V.,Venkatasubramanian, G., & Reddy, Y. C. J. (2013).Clinical correlates of caudate volume in drug-naive adult patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder.Psychiatry Research-Neuroimaging, 212(1), 7–13.

Nardini, M., Burgess, N., Breckenridge, K., & Atkinson, J.(2006). Differential developmental trajectories for egocentric,environmental and intrinsic frames of reference in spatial memory.Cognition, 101(1), 153–172.

Nemmi, F., Boccia, M., Piccardi, L., Galati, G., & Guariglia,C. (2013). Segregation of neural circuits involved in spatial learning in reaching and navigational space.Neuropsychologia, 51(8), 1561–1570.

Nunez, R. E., & Cornejo, C. (2012). Facing the sunrise:Cultural worldview underlying intrinsic-based encoding of absolute frames of reference in aymara.Cognitive Science,36(6), 965–991.

O'Brien, J. L., O'Keefe, K. M., LaViolette, P. S., DeLuca, A.N., Blacker, D., Dickerson, B. C., & Sperling, R. A. (2010).Longitudinal fmri in elderly reveals loss of hippocampal activation with clinical decline.Neurology, 74(24), 1969–1976.

O'Keefe, J., & Nadel, L. (1978).The hippocampus as a cognitive map. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Pasqualotto, A., Spiller, M. J., Jansari, A. S., & Proulx, M. J.(2013). Visual experience facilitates allocentric spatial representation.Behavioural Brain Research, 236, 175–179.

Pertzov, Y., Avidan, G., & Zohary, E. (2011). Multiple reference frames for saccadic planning in the human parietal cortex.Journal of Neuroscience, 31(3), 1059–1068.

Piaget, J., & Inhelder, B. (1997).The child's conception of space. London: Routledge.

Picucci, L., Caffo, A. O., & Bosco, A. (2011). Besides navigation accuracy: Gender differences in strategy selection and level of spatial confidence.Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31(4), 430–438.

Pilly, P. K., & Grossberg, S. (2012). How do spatial learning and memory occur in the brain? Coordinated learning of entorhinal grid cells and hippocampal place cells.Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 24(5), 1031–1054.

Portugal, E. M. M., Cevada, T., Monteiro, R. S., Guimaraes,T. T., Rubini, E. D., Lattari, E., & Deslandes, A. C. (2013).Neuroscience of exercise: From neurobiology mechanisms to mental health.Neuropsychobiology, 68(1), 1–14.

Ramos, J. M. J. (2008). Hippocampal damage impairs long-term spatial memory in rats: Comparison between electrolytic and neurotoxic lesions.Physiology & Behavior,93(4-5), 1078–1085.

Rosenthal, H. E. S., Norman, L., Smith, S. P., & McGregor,A. (2012). Gender-based navigation stereotype improves men's search for a hidden goal.Sex Roles, 67(11-12),682–695.

Seubert, J., Humphreys, G. W., Mueller, H. J., & Gramann, K.(2008). Straight after the turn: The role of the parietal lobes in egocentric space processing.Neurocase, 14(2),204–219.

Siegel, A. W., & White, S. H. (1975). The development of spatial representations of large-scale environments.Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 10, 9.

Simonnet, M., Vieilledent, S., & Tisseau, J. (2013).Influences of subjects activity and environmental features on spatial encoding.Annee Psychologique, 113(2), 227–254.

Takahashi, N., & Kawamura, M. (2002). Pure topographical disorientation - the anatomical basis of landmark agnosia.Cortex, 38(5), 717–725.

Taube, J. S., Valerio, S., & Yoder, R. M. (2013). Is navigation in virtual reality with fmri really navigation?Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 25(7), 1008–1019.

Taube, J. S., Wang, S. S., Kim, S. Y., & Frohardt, R. J.(2013). Updating of the spatial reference frame of head direction cells in response to locomotion in the vertical plane.Journal of Neurophysiology, 109(3), 873–888.

Thelen, E., & Smith, L. B. (1996).A dynamic systems approach to the development of cognition and action. MIT Press.

Umemoto, A., Scolari, M., Vogel, E. K., & Awh, E. (2010).Statistical learning induces discrete shifts in the allocation of working memory resources.Journal of Experimental Psychology-Human Perception and Performance, 36(6),1419–1429.

Villablanca, J. R. (2010). Why do we have a caudate nucleus?Acta Neurobiologiae Experimentalis, 70(1), 95–105.

Whitlock, J. R., Sutherland, R. J., Witter, M. P., Moser, M.-B.,& Moser, E. I. (2008). Navigating from hippocampus to parietal cortex.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(39), 14755–14762.

Wiggett, A. J., Downing, P. E., & Tipper, S. P. (2013).Facilitation and interference in spatial and body reference frames.Experimental Brain Research, 225(1), 119–131.

Wilson, K. D., Woldorff, M. G., & Mangun, G. R. (2005).Control networks and hemispheric asymmetries in parietal cortex during attentional orienting in different spatial reference frames.Neuroimage, 25(3), 668–683.

Wolbers, T., & Buchel, C. (2005). Dissociable retrosplenial and hippocampal contributions to successful formation of survey representations.Journal of Neuroscience, 25(13),3333–3340.

Wolbers, T., Wiener, J. M., Mallot, H. A., & Buchel, C.(2007). Differential recruitment of the hippocampus,medial prefrontal cortex, and the human motion complex during path integration in humans.Journal of Neuroscience,27(35), 9408–9416.

Zaehle, T., Jordan, K., Wuestenberg, T., Baudewig, J.,Dechent, P., & Mast, F. W. (2007). The neural basis of the egocentric and allocentric spatial frame of reference.Brain Research, 1137(1), 92–103.