Women and exercise in aging

Kristina L.Kendall,Ciaran M.Fairman

Department of Health and Kinesiology,Georgia Southern University,Statesboro,GA 30458,USA

Women and exercise in aging

Kristina L.Kendall*,Ciaran M.Fairman

Department of Health and Kinesiology,Georgia Southern University,Statesboro,GA 30458,USA

Aging is associated w ith physiological declines,notably a decrease in bone mineral density(BMD)and lean body mass,w ith a concurrent increase in body fatand centraladiposity.Interest in women and aging is of particular interestpartly as a resultof gender specific responses to aging,particularly as a result of menopause.It is possible that the onset of menopause may augment the physiological decline associated w ith aging and inactivity.More so,a higher incidence of metabolic syndrome(an accumulation of cardiovascular disease risk factors including obesity,low-density lipoprotein cholesterol,high blood pressure,and high fasting glucose)has been shown in m iddle-aged women during the postmenopausal period.This is due in part to the drastic changes in body composition,as previously discussed,but also a change in physical activity(PA)levels.Sarcopenia is an age related decrease in the cross-sectionalarea of skeletalmuscle fibers thatconsequently leads to a decline in physical function,gaitspeed,balance,coordination,decreased BMD,and quality of life.PA plays an essential role in combating physiological decline associated w ith aging.Maintenance of adequate levels of PA can result in increased longevity and a reduced risk for metabolic disease along w ith other chronic diseases.The aim of this paper is to review relevant literature,examine current PA guidelines,and provide recommendations specific to women based on current research.

Aerobic;Exercise prescription;Flexibility;Older adults;Strength training

1.Introduction

It is anticipated that there w illbe almost89 million people 65 years old or above by the year 2050.1As the number of elderly people worldwide increases,2interest in health related outcomes of aging has concurrently increased.It has been suggested that an age-associated decline in physical function, cardiorespiratory fi tness,and muscle mass may accelerate the physiological decline in later decades of life3and lead to an increase in morbidity and mortality rates.2,4

Women are of particular interest due to some gender differences accompanying aging,particularly as a result of menopause.Physiological decline,particularly a reduction in bone m ineral density(BMD)can be attributed to estrogen deficiency as a resultof menopause.5Reductions in BMD put olderwomen at risk forosteoporosis which can lead to balance and gait issues,a higher risk of injury,subsequent financial costs,6and even a higher risk of mortality.2More so,a decrease in muscle strength in combination w ith reduced BMD can further impair balance and mobility,leading to a decline in functional capacity.7Thus,it becomes apparent of the need for resistance training to attenuate the decline in lean mass,muscle mass,and BMD that accompany aging and inactivity.Other physiological changes that occur w ith aging are alterations to the cardiovascular(CV)system,which can further impair functional capacity.Remarkably,by the age of 75 years,more than half of the functional capacity of the CV system has been lost,8leading to VO2maxvalues lower than that which is required for many common activities of dailyliving.9More than just leading to decreases in quality of life, low cardiorespiratory fi tness has been associated w ith CV disease and all-cause mortality.10—12The CV system remains adaptable atany age,13,14w ith relative increases in VO2maxin older populations equivalent to those seen in younger individuals.

Physical activity(PA)has long been associated w ith the attenuation of physical decline associated w ith aging.15The purpose of this article is to:

1.Exam ine the decline in physiological variables associated w ith aging and a sedentary lifestyle.

2.Review recent research investigating exercise interventions on health related components in women.

3.Provide recommendations for PA that build on prior research and guidelines to improve physiological functioning in aging women.

2.Physiological decline w ith aging and inactivity

Aging is associated w ith physiological declines,notably a decrease in BMD and lean body mass(LBM),w ith a concurrent increase in body fatand centraladiposity.16,17Itispossible that the onset of menopause may augment the decline in physiologicaldecline associated w ith aging and inactivity.5Wang and colleagues18compared almost 400 early postmenopausal women and found higher levels of total body fat,as well as abdom inaland android fat in postmenopausalwomen.Consequently,the authorscould notconclude thatthe changes in body fatwere related to menopause ormerely a resultofaging alone. The authors did note,however,that changes in fat-free mass (FFM),including bone mass,may be attributed to menopauserelated mechanisms,including deficienciesin grow th hormones and estrogen.Douchi et al.5had sim ilar findings when comparing body composition variables between pre-and postmenopausal women.The authors demonstrated an increase in percentage of body fat(30.8%±7.1%vs.34.4%±7.0%), trunk fatmass(6.6±3.9 kgvs.8.5±3.4 kg),and trunk—leg fat ratio(0.9±0.4vs.1.3±0.5)w ith aging.Concurrently,they found that lean mass(right arm,trunk,bilateral legs,and total body(34.5±4.3 kgvs.32.5±4.0 kg))also declined w ith age. Bakerand colleagues19found that femaleshad a greaterdecline in BMD w ith age compared to males.More so,a higher incidence of metabolic syndrome(an accumulation of cardiovascular disease risk factors including obesity,low-density lipoprotein cholesterol(LDL-C),high blood pressure,and high fasting glucose)has been shown in m iddle-aged women during the postmenopausal period.This is due in part to the drastic changesin body composition,as previously discussed,butalso a change in PA levels.In a longitudinal study of over 77,000 (34—59 years)women spanning 24 years,van Dam et al.20found high body mass index(BM I,25+)and lower levels of PA(<30 min/day ofmoderate to vigorous intensity activity)to be attributed with a higher risk of CV disease,cancer,and allcause mortality.Furthermore,Sisson etal.21found higher levels of sedentary behavior(<4 h/day)associated w ith a 54% increase in risk for metabolic syndrome only in those women notmeeting national guidelines.

Sarcopenia is an age related decrease in the cross-sectional area of skeletal muscle fibers that consequently leads to a decline in physical function,gaitspeed,balance,coordination, decreased bone density,and quality of life.22Additionally,due to lower levels of vigorous activity,aging populations experience notably higher losses in type II fibers than type I fibers,23which can reduce strength,speed,power,and overall PA.Subsequently,maintenance ofmuscle mass and strength is imperative to maintain a high quality level of physical functioning,and attenuate measures of frailty.Muscular adaptations to exercise(increase in muscle size,cross-sectionalarea, and consequent strength)may counteract muscle loss and physical decline associated w ith sarcopenia.

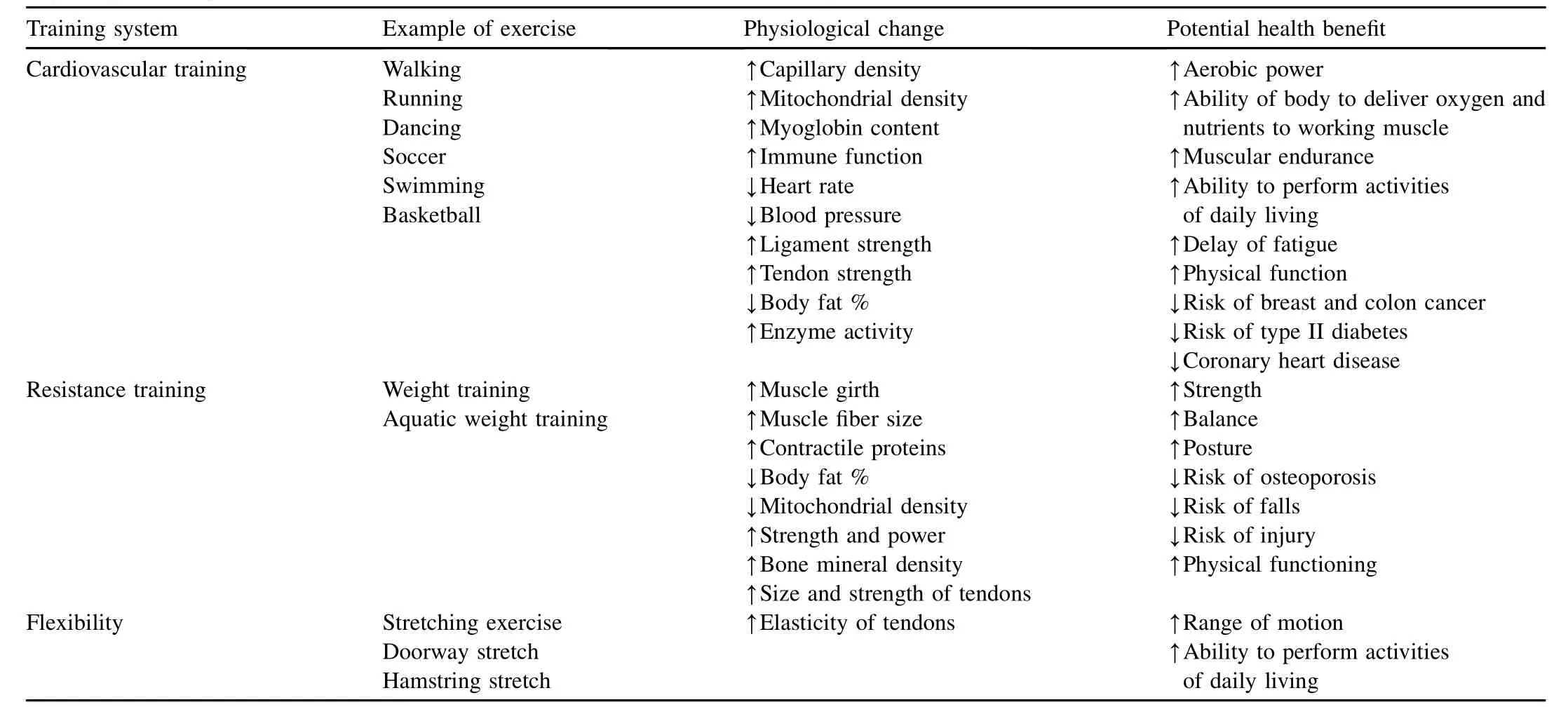

Thus it appears that PA plays a pivotal role in the attenuation of physical decline and can potentially improve physical functioning and quality of life w ith age.24,25Furthermore, maintenance of adequate levels of PA can result in increased longevity,and a reduced risk for metabolic disease along w ith other chronic diseases.A list of physiological changes associate w ith differentmodes of activity and their potentialhealth outcome are listed in Table 1.26—28

3.CV exercise

CV disease is the major cause of death in older women.29—31It therefore becomes of utmost importance to decrease the risk for CV disease.Cross-sectional and intervention studies have repeatedly shown that endurance training can improve insulin sensitivity,32,33lower blood pressure,34improve lipid profi les,35—37and decrease body fat,36—38all factors related to CV disease.Furthermore,aerobic exercise has been shown to increase VO2max,an index of cardiorespiratory fi tness that on average decreases 5%—15%per decade after the age of 25.39These physiological responses to aerobic exercise results in an increased efficiency of the system during exercise(increased stroke volume,capillary,and m itochondrial density;lower heart rate and blood pressure)and ability to better deliver oxygen and glucose to working muscles.40

In an investigation into the levelofactivity thatmay protect against CV disease mortality,Hamer and Stamatakis41recruited 23,747 men and women w ithout a known history of CV disease at baseline.The researchers tracked PA levels and causes of death over a period of 7.0± 3.0 years.By calculating a hazard ratio(HR),the authors found that a m inimum of two sessions of moderate to vigorous PA per week was associated w ith a reduced risk of CV disease and all-cause mortality.Compared to active adults,those individuals who were inactive were at elevated risk of CV disease(HR of 1.41vs.active:HR of 0.82)and all-cause mortality(HR of 1.50vs.active:HR of 1.11).Supporting these findings,several studies have demonstrated walking,or walk—jogging,for 30—60 m in,2—5 days per week can significantly decrease body weight,increase BMD and VO2max,and improve glucose levels in older women.42—45

Table 1 Physiological changes and health benefi ts associated w ith different modes of activity.26—28

A lthough reaching current recommended PA levels(30 m in of moderate activity 5 days/week,or 20 min vigorous activity 3 days/week)is sufficient forpartially reducing risk factors for CV disease,it does not eliminate the additional risk that overweight/obesity poses.46Thus increasing levels of PA in order to improve body composition may further reduce the risk of CV disease and mortality.Martins et al.47found that 16 weeks of aerobic training for 45 m in,3 days per week,progressing from 40%to 50%HR reserve to 71%—85%HR reserve significantly improved waist circum ference(pre: 93.3±9.9 cm,post:90.0±8.6 cm),in addition to upper body strength(number of arm curl repetitions in 30 s(pre:15±4, post:20±5)),lower body strength(number of chair stand repetitions in 30 s(pre:12±4,post:18±4))and aerobic endurance,as measured by a 6-min walk test(pre: 380± 75 m,post:438± 85 m).Sixteen weeks after the cessation of the training program,body mass,LDL,and C-reactive protein(CRP)were significantly lower than baseline values(body mass:73.1±11.9 kgvs.72.2±11.4 kg; LDL:79.8± 32.0 mg/dLvs.55.3± 17.6 mg/dL;CRP: 3.38±1.48 mg/Lvs.1.39±1.35 mg/L).This highlights the need to gradually progress the intensity of aerobic training over time to allow for adequate metabolic adaptations to occur.

Evaluating differentmodalities foraerobic training,Bocalini etal.48compared the effects of land(LE)versus water-based (WE)aerobic exercise in sedentary older women over the course of 12 weeks(3 days/week at~70%of age-predicted HRmax).A lthough VO2max,lower body strength,and agility significantly improved in both groups,only the WE group saw a significant decrease in resting HR(pre:92± 2 bpm,post: 83±3 bpm),a significantincrease in upperbody strength(arm curl test,pre:17±3 repetitions,post:25±1 repetitions),and improved markers of flexibility,both lowerbody(sit-and-reach, pre:24±3 cm,post:36±2 cm)and upperbody(back scratch, pre:-10±2 cm,post:-6±2 cm),suggesting its use as an alternative to traditionalaerobic training.More so,walking in conjunction with other aerobic exercise forms,such as sw imm ing,cycling,or dancing,resulted in improving VO2maxand blood pressure,49favorable changes in lipids,49and improved muscle strength and endurance,flexibility,and balance.39

4.Strength training

A fter the age of 30,a decrease in muscle size and thickness, along w ith an increase in intramuscular fat takes place.50The loss of muscle mass,resulting from a decreased number of muscle fibers and atrophy of remaining muscle fibers(sarcopenia),has a strong role in the loss of strength,as wellas the ability to perform activities of daily living.51,52The decline in isometric and dynam ic muscle strength is a consequence of the aging process,w ith approximately 30%of strength lost between the ages of 50 and 70 years.53Furthermore,crosssectional data suggest that muscle strength declines by approximately 15%per decade in the 6th and 7th decade,and 30%thereafter.54—57Resistance training(RT)has increased its popularity among older adults because of its benefi ts on muscle fi tness,body composition,mobility,and functional capacity.More so,regular RT can offset the typical ageassociated decline in bone health by maintaining or increasing BMD and total body m ineral content.58

A lthough there is little question as to the benefi ts of RT in an older population,there is still some disparity regarding the ideal training volume(i.e.,number of sets,repetitions,and load).59,60Previous research has shown thatolderwomen who resistance train intensely(80%1-RM)three times per week (whole-body RT,including elbow flexion and extension,seated row,overhead press,leg extension and curl,bench press,and situps)have sim ilar improvements in FFM and total body strength.Hunter and colleagues61demonstrated a 1.8-kg increase in FFM for the high-resistance group,compared to an increase of 1.9 kg for the variable-resistance group.Additionally,they observed a training effect for all 1-RM tests (seated press,26.6%;bench press,28.5%;arm curl,63.7%; and leg press,37.1%).Interestingly,those who trained w ith a variable resistance demonstrated an increase in ease of performing daily tasks over those who trained intensely three times per week.These findings suggest that training too intensely or too frequently may result in increased fatigue and consequently a reduced training adaptation in older women due to insufficient time to recover.

Low volume training(LV,1 set per exercise)compared to high volume training(HV,3 sets perexercise)performed tw ice a week for 13 weeks induced similar improvements in maximal dynam ic strength for knee extensors and elbow flexion,muscular activation of the vastus medialis and the biceps brachii,and muscle thickness for the knee extensors and elbow flexors in elderly women.62The authors suggest that during the initial months of training,elderly women can significantly increase upper-and lower-body strength by utilizing low volume training.However,after longer periods of training,larger muscle groups may require greater training volume to provide further strength gains.63,64

Allow ing individuals to self-regulate their exercise intensity to a preferred intensity may lead to greater enjoyment and stronger compliance to an exercise program.65—67Additionally,it has been suggested that a low-intensity resistance exercise protocol may be more effective for older adults by increasing adherence rates.68,69Compared to a high intensity resistance exercise program,lower attrition rates were observed when training used lower intensities(70%vs.80% 1-RM)and frequencies(2vs.3 days).70However,Elsangedy and colleagues71recently found thatolder women engaged in an RT program that allowed them to self-select their training load selected loads thatwere less than that recommended for improvements in muscle strength and endurance(42%1-RM compared to 50%—70%1-RM).While this intensity is suitable for very deconditioned individuals,it may not provide enough overload to the body to elicit changes in strength and functional capacity.Though limited data exist on the chronic effects of self-selected training load on muscular fi tness and functionalautonomy,a recentstudy by Storer etal.72observed significant improvements LBM,upper body strength,peak leg power,and VO2maxin m iddle-aged males using a personal trainer compared to self-training.Albeit using males,this study supports the idea that guidance from a personal trainer and the use of a progressive overload,in which intensity is gradually increased over time,may be optimal to maxim ize chronic positive effects.

Traditional strength training,including the use of weight machines,has been shown to induce positive changes in strength and FFM in older adults.38,73,74However,it becomes imperative to provide alternative methods of RT to the traditionaluse ofweightmachines,which may be more convenient for certain populations,including older women.In a recent study by Colado et al.,75the authors exam ined three forms of RT(traditional weight machines(WM),elastic bands(EB), and aquatic devices(AD))and compared their effectiveness at improving body composition and physical capacity.Follow ing the 10-week training program,all three groups reduced FM (WM:5.15%,EB:1.93%,and AD:2.57%),increased FFM (WM:2.52%,EB:1.15%,AD:0.51%),in addition to upperand lower-body strength,w ith m inimal differences between the different groups.

5.Flexibility

Flexibility training has been shown to improve muscle and connective tissue properties,reduce joint pain,and alter muscle recruitment patterns.76Although results from previous studies examining changes in flexibility following an intervention have provided mixed results,more recentstudies have demonstrated significant improvements in range of motion of various joints in older adults participating in regular exercise.77—79While the research exam ining interventions for improving flexibility in an older population is limited,increases of 5%—25%have been shown follow ing interventions using a combination of aerobic exercise,RT,and stretching.80,81The typical duration for each exercise session was 60 m in,performed 3 days per week for 12 weeks to 1 year. Filho etal.82examined the effects of16 weeks of combination (aerobic,flexibility,and resistance)training on metabolic parameters and functionalautonomy in elderly women.Twentyone women(68.9±6.8 years)participated in three weekly sessions of stretching,resistance exercise,and moderate intensity walking for 16 weeks.Significant improvements in metabolic parameters,including glucose,triglycerides,total cholesterol,high density lipoproteins,LDL,blood pressure, and BM I were seen follow ing the intervention.More so,the addition of resistance and flexibility exercises appeared to enhance functional autonomy(the ability to perform activities of daily living).Supporting these findings,Bravo etal.80found that flexibility,agility,strength,and endurance allsignificantly improved follow ing 12 months of an exercise program,in which participants performed weight bearing exercises (walking and stepping),aerobic dancing,and flexibility exercises for 60 min three times a week.The exercise group was also able to maintain spinal BMD while control groups saw significant reductions.Furthermore,in a study by Hopkins et al.,8165 older women participated in a 12-week exercise program,consisting of low-impact aerobics,stretching,and progressive dance movements.Each session was 50 m in long and was performed three times perweek.The exercising group significantly improved cardiorespiratory endurance,strength, balance,flexibility,agility,and body fat.

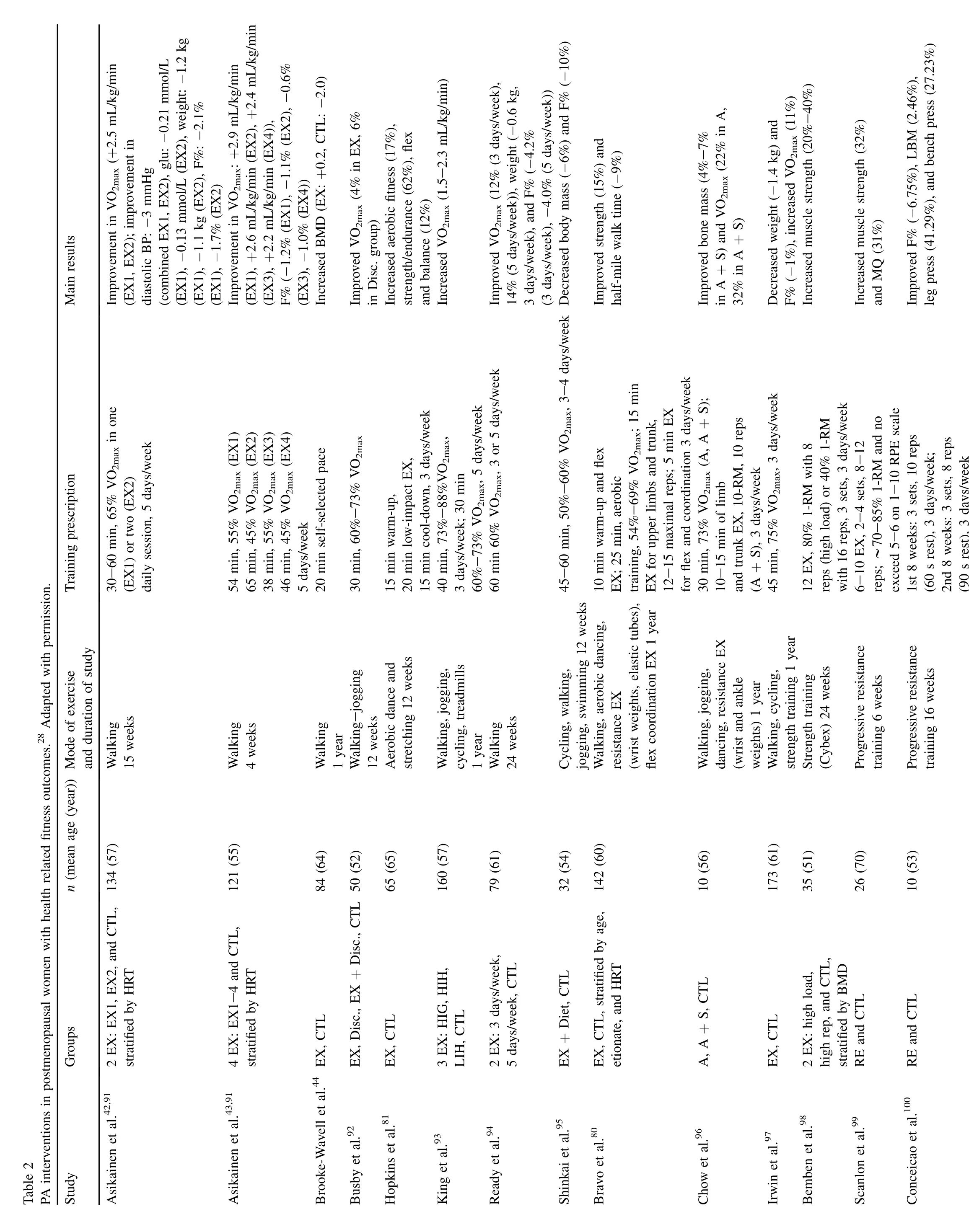

The aforementioned fi ndings primarily include“combination”training where interventions include aerobic and/or RT w ith flexibility training.Thus we cannot deduce what effect flexibility training alone had.However,combination training has been shown to be justas beneficial to flexibility as flexibility training alone.83,84Therefore,w ith the positiveadaptations from RT and aerobic training,the addition of flexibility training to an exercise intervention is warranted, and may improve functional autonomy,range of motion, balance,and mobility in older women(Table 2).26

?

6.Recommendation

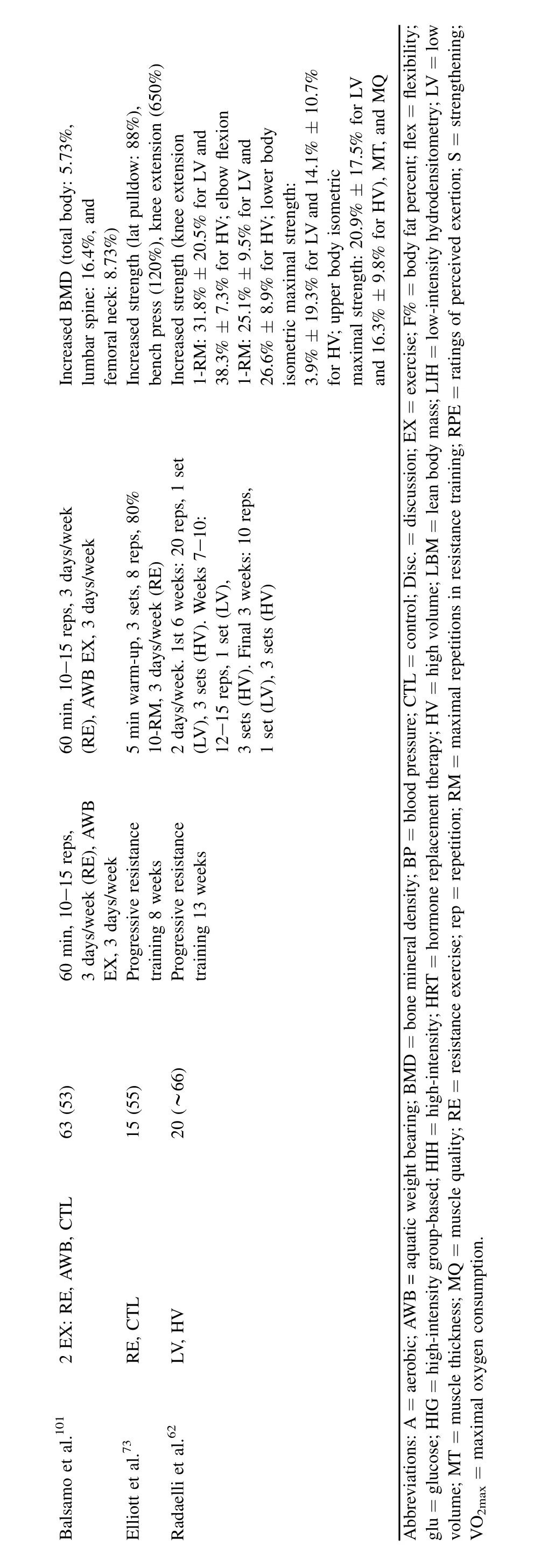

While current American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM)guidelines recommend light-to moderate-intensity activities to optim ize health,moderate-to high-intensity exercise may be necessary to elicit positive CV adaptations and reduce the risk for CV disease.Older adults should aim to get at least 30 m in of moderate activity,or 20 m in of more vigorous activity(≥6 METS or 60%—<90%HRR),3 days a week.It is recommended that programs include low-impact, large muscle,rhythmic forms of exercise,including sw imming,walking,biking,and dancing.More so,women may benefi t from participating in group-based fi tness classes,such as step aerobics and dance classes.Social support and group cohesiveness received from group fi tness classes may help to increase self-efficacy,leading to long term adherence as well as greater enjoyment and satisfaction from the exercise program.85—87The addition of stretching exercises(light-to moderate-intensity,hold for 30 s each muscle group,3—4 repetitions)to these programs can serve to increase flexibility and range of motion.

ACSM recommends thatolder adults perform RT at least2 non-consecutive days per week,including 8—10 exercises involving all the major muscle groups at moderate intensity (selecting a weight that allows 10—15 repetitions of each exercise),w ith 2—3 m in of rest between each set.Additionally, those who are very deconditioned could start RT w ith a“very light”to“light”intensity(40%—50%1-RM)to improve strength,power,and balance.27It is advised that women unfam iliar w ith RT consult a fi tness professional prior to beginning a program.It is suggested that one must use progressive overload to stimulate muscular adaptations to resistance exercise.Typical recommendations for progression of RT is to fi rst increase repetitions,followed by an increase in weight(0.5 kg for upper body,1 kg for lower body)per week. For optimal results from a resistance program,the focus should be on full-body,compound movements(bench press, squat,pull-ups,etc.).Furthermore,adherence to group-based RT programs tends to be higher among older women than home based programs.88,89Additionally,Elsangedy and colleagues71recently found that women who self-selected resistance exercise intensity fell below current ACSM guidelines. Consequently,the participation in a supervised orgroup-based resistance exercise program may improve women’s adherence and health benefi ts stemm ing from a higher intensity attained. Finally,the authors propose circuit training,which incorporates both RTand aerobics,as an attractive alternative for weight training.One of the majorbenefi ts to circuit training is that it can illicit the same positive physiological responses as traditional RT,thus providing a time-efficient alternative to improve muscular strength and functional fi tness.90

Table 3 Recommendations for exercise based on current research.

The ACSM recommendations for flexibility are to aim for greater than 2—3 days per week,ultimately aim ing for daily training.Static stretching should be held 10—30 s ata pointof m ild discom fort,although stretches lasting 30—60 s may provide additional benefi ts.Two to four repetitions per exercise are recommended,aim ing for at least 60 s of stretching for each major muscle-tendon unit(Table 3).27

The recommendations we have provided are general.The frequency,intensity,type,and duration of exercise one is able to achieve and maintain w ill vary from person to person.Thus we suggest thatan individualized approach be utilized.While some activity is better than none,individuals aim ing to improve CV health,muscular strength and endurance,and functional mobility should strive to meet the m inimum recommendations we have provided.

1.Jacobsen LA,Kent M,Lee M,Mather M.America’s aging population.Popul Bull2011;66:2—16.

2.Quirino MA,Modesto-Filho J,de Lima Vale SH,A lves CX,Leite LD, Brandao-Neto J.Influence of basal energy expenditure and body composition on bone m ineral density in postmenopausal women.Int J Gen Med2012;5:909—15.

3.Weiss EP,Spina RJ,Holloszy JO,Ehsani AA.Gender differences in the decline in aerobic capacity and its physiologicaldeterminants during the later decades of life.J Appl Physiol(1985)2006;101:938—44.

4.Rossi AP,Watson NL,Newman AB,Harris TB,Kritchevsky SB, Bauer DC,et al.Effects of body composition and adipose tissue distribution on respiratory function in elderly men and women:the health, aging,and body composition study.J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2011;66:801—8.

5.Douchi T,Yamamoto S,Yoshim itsu N,Andoh T,Matsuo T,Nagata Y. Relative contribution of aging and menopause to changes in lean and fat mass in segmental regions.Maturitas2002;42:301—6.

6.Nelson ME,Rejeski WJ,Blair SN,Duncan PW,Judge JO,King AC, et al.Physical activity and public health in older adults—recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association.Circulation2007;116:1094—105.

7.Karinkanta S,Heinonen A,Sievanen H,Uusi-Rasi K,Fogelholm M, Kannus P.Maintenance of exercise-induced benefi ts in physical functioning and bone among elderly women.Osteoporos Int2009;20:665—74.

8.Barnard RJ,Grimditch GK,Wilmore JH.Physiological characteristics of sprint and endurance masters runners.Med Sci Sports1979;11:167—71.

9.Durstine JL,Moore GE,editors.ACSM’s Exercise Management for Persons with Chronic Diseases and Disabilities.Champaign(IL): Human Kinetics;2003.

10.Paffenbarger Jr RS,Wing AL,Hyde RT.Physicalactivity as an index of heart attack risk in college alumni.Am J Epidemiol1978;108:161—75.

11.Blair SN,Kampert JB,Kohl 3rd HW,Barlow CE,Macera CA, Paffenbarger Jr RS,etal.Influences of cardiorespiratory fi tness and other precursors on cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in men and women.J Am Med Assoc1996;276:205—10.

12.Myers J,Prakash M,Froelicher V,Do D,Partington S,Atwood JE. Exercise capacity and mortality among men referred for exercise testing.N Engl J Med2002;346:793—801.

13.Makrides L,Heigenhauser GJ,Jones NL.High-intensity endurance training in 20-to 30-and 60-to 70-yr-old healthy men.J Appl Physiol (1985)1990;69:1792—8.

14.Kohrt WM,Malley MT,Coggan AR,Spina RJ,Ogawa T,Ehsani AA, et al.Effects of gender,age,and fi tness level on response of VO2maxto training in 60—71 yr olds.J Appl Physiol(1985)1991;71:2004—11.

15.Booth FW,Laye MJ,Roberts MD.Lifetime sedentary living accelerates some aspects of secondary aging.J Appl Physiol2011;111:1497—504.

16.Kim KZ,Shin A,Lee J,Myung SK,Kim J.The benefi cial effect of leisure-time physical activity on bone m ineral density in pre-and postmenopausal women.Calcified Tissue Int2012;91:178—85.

17.Nassis GP,Geladas ND.Age-related pattern in body composition changes for 18—69 year old women.J Sports Med Phys Fitness2003;43:327—33.

18.Wang Q,Hassager C,Ravn P,Wang S,Christiansen C.Totaland regional body-composition changes in early postmenopausal women:age-related or menopause-related?Am J Clin Nutr1994;60:843—8.

19.Baker JF,Davis M,A lexander R,Zemel BS,Mostoufi-Moab S,Shults J, et al.Associations between body composition and bone density and structure in men and women across the adult age spectrum.Bone2013;53:34—41.

20.van Dam RM,Li T,Spiegelman D,Franco OH,Hu FB.Combined impact of lifestyle factors on mortality:prospective cohort study in US women.Br Med J2008;337:a1440.http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bm j.a1440.

21.Sisson SB,Camhi SM,Church TS,Martin CK,Tudor-Locke C, Bouchard C,et al.Leisure time sedentary behavior,occupational/domestic physical activity,and metabolic syndrome in U.S.men and women.Metab Syndr Relat Disord2009;7:529—36.

22.Hughes VA,Frontera WR,Wood M,Evans WJ,DallalGE,Roubenoff R, et al.Longitudinalmuscle strength changes in older adults:infl uence of muscle mass,physicalactivity,and health.J Gerontol A BiolSciMed Sci2001;56:B209—17.

23.Doherty TJ.Aging and sarcopenia.JApplPhysiol(1985)2003;95:1717—27.

24.Curl WW.Aging and exercise:are they compatible in women?Clin Orthop Relat R2000;372:151—8.

25.DiPietro L.Physical activity in aging:changes in patterns and their relationship to health and function.J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2001;56:13—22.

26.Stathokostas L,Little RM,Vandervoort AA,Paterson DH.Flexibility training and functional ability in older adults:a systematic review.J Aging Res2012;2012:306818.http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/306818.

27.Garber CE,Blissmer B,Deschenes MR,Franklin BA,Lamonte MJ, Lee IM,et al.American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintainingcardiorespiratory,musculoskeletal,and neuromotor fi tness in apparently healthy adults:guidance for prescribing exercise.Med Sci Sports Exerc2011;43:1334—59.

28.Asikainen TM,Kukkonen-Harjula K,M iilunpalo S.Exercise for health for early postmenopausal women:a systematic review of random ised controlled trials.Sports Med2004;34:753—78.

29.M ieres JH,Shaw LJ,AraiA,Budoff MJ,Flamm SD,Hundley WG,etal. Role of noninvasive testing in the clinical evaluation of women w ith suspected coronary artery disease:consensus statement from the Cardiac Imaging Comm ittee,Council on Clinical Cardiology,and the Cardiovascular Imaging and Intervention Comm ittee,Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention,American Heart Association.Circulation2005;111:682—96.

30.Stampfer M J,Hu FB,Manson JE,Rimm EB,Willett WC.Primary prevention of coronary heartdisease in women through dietand lifestyle.N Engl J Med2000;343:16—22.

31.Castelli WP.Cardiovascular disease in women.Am J Obstet Gynecol1988;158(6 Pt2):1553—60.1566—7.

32.Stevenson ET,Davy KP,Seals DR.Hemostatic,metabolic,and androgenic risk factors for coronary heartdisease in physically active and less active postmenopausal women.ArteriosclerThrombVascBiol1995;15:669—77.

33.Tonino RP.Effectof physical-training on the insulin resistance of aging.Am J Physiol1989;256:E352—6.

34.Hagberg JM,Park JJ,Brown MD.The role of exercise training in the treatment of hypertension:an update.Sports Med2000;30:193—206.

35.Katzel LI,Bleecker ER,Colman EG,Rogus EM,Sorkin JD,Goldberg AP. Effects of weight lossvs.aerobic exercise training on risk factors for coronary disease in healthy,obese,m iddle-aged and older men.A random ized controlled trial.J Am Med Assoc1995;274:1915—21.

36.Seals DR,A llen WK,Hurley BF,Dalsky GP,Ehsani AA,Hagberg JM. Elevated high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in older endurance athletes.Am J Cardiol1984;54:390—3.

37.Seals DR,Hagberg JM,Hurley BF,Ehsani AA,Holloszy JO.Effects of endurance training on glucose tolerance and plasma lipid levels in older men and women.J Am Med Assoc1984;252:645—9.

38.Bemben DA,Bemben MG.Effects of resistance exercise and body mass index on lipoprotein-lipid patterns of postmenopausalwomen.J Strength Cond Res2000;14:80—6.

39.Heath GW,Hagberg JM,Ehsani AA,Holloszy JO.A physiological comparison of young and olderendurance athletes.J ApplPhysiolRespir Environ Exerc Physiol1981;51:634—40.

40.PowellKE,Paluch AE,Blair SN.Physicalactivity forhealth:whatkind? How much?How intense?On top of what?Annu Rev Public Health2011;32:349—65.

41.Hamer M,Stamatakis E.Low-dose physical activity attenuates cardiovascular disease mortality in men and women with clustered metabolic risk factors.Circ-cardiovasc Qual2012;5:494—9.

42.Asikainen TM,M iilunpalo S,Oja P,Rinne M,Pasanen M,Vuori I. Walking trials in postmenopausal women:effect of onevs.two daily bouts on aerobic fi tness.Scand J Med Sci Sports2002;12:99—105.

43.Asikainen TM,M iilunpalo S,Oja P,Rinne M,Pasanen M,Uusi-Rasi K, etal.Randomised,controlled walking trials in postmenopausalwomen: the m inimum dose to improve aerobic fi tness?Br J Sports Med2002;36:189—94.

44.Brooke-Wavell K,Jones PR,Hardman AE.Brisk walking reduces calcaneal bone loss in post-menopausal women.Clin Sci(Lond)1997;92:75—80.

45.Hatori M,Hasegawa A,Adachi H,Shinozaki A,Hayashi R,Okano H, et al.The effects of walking at the anaerobic threshold level on vertebral bone loss in postmenopausal women.Calcif Tissue Int1993;52:411—4.

46.Akbartabartoori M,Lean MEJ,Hankey CR.The associations between current recommendation for physical activity and cardiovascular risks associated with obesity.Eur J Clin Nutr2008;62:1—9.

47.Martins RA,Neves AP,Coelho-Silva M J,Verissimo MT,Teixeira AM. The effect of aerobic versus strength-based training on high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in older adults.Eur J Appl Physiol2010;110:161—9.

48.Bocalini DS,Serra AJ,Murad N,Levy RF.Water-versus land-based exercise effects on physical fi tness in older women.Geriatr Gerontol Int2008;8:265—71.

49.Lindheim SR,Notelovitz M,Feldman EB,Larsen S,Khan FY,Lobo RA. The independent effects of exercise and estrogen on lipids and lipoproteins in postmenopausal women.Obstet Gynecol1994;83:167—72.

50.Imamura K,Ashida H,Ishikawa T,Fujii M.Human major psoas muscle and sacrospinalis muscle in relation to age:a study by computed tomography.J Gerontol1983;38:678—81.

51.Aagaard P,Suetta C,Caserotti P,Magnusson SP,K jaer M.Role of the nervous system in sarcopenia and muscle atrophy with aging:strength training as a countermeasure.Scand J Med Sci Sports2010;20:49—64.

52.Andersen JL.Muscle fibre type adaptation in the elderly human muscle.Scand J Med Sci Sports2003;13:40—7.

53.Larsson L,Grimby G,Karlsson J.Muscle strength and speed of movement in relation to age and muscle morphology.J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol1979;46:451—6.

54.Larsson L.Morphological and functional characteristics of the ageing skeletal muscle in man.A cross-sectional study.Acta Physiol Scand Suppl1978;457:1—36.

55.Murray MP,Duthie Jr EH,Gambert SR,Sepic SB,Mollinger LA.Agerelated differences in knee muscle strength in normalwomen.J Gerontol1985;40:275—80.

56.Danneskiold-Samsoe B,Kofod V,Munter J,Grimby G,Schnohr P, Jensen G.Muscle strength and functional capacity in 78—81-year-old men and women.Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol1984;52:310—4.

57.Harries UJ,Bassey EJ.Torque—velocity relationships for the knee extensors in women in their3rd and 7th decades.Eur JAppl PhysiolOccup Physiol1990;60:187—90.

58.Nelson ME,Fiatarone MA,Morganti CM,Trice I,Greenberg RA, Evans WJ.Effects of high-intensity strength training on multiple risk factors for osteoporotic fractures.A randomized controlled trial.J Am Med Assoc1994;272:1909—14.

59.Hass CJ,Feigenbaum MS,Franklin BA.Prescription of resistance training for healthy populations.Sports Med2001;31:953—64.

60.Marshall PW,M cEwen M,Robbins DW.Strength and neuromuscular adaptation follow ing one,four,and eightsets of high intensity resistance exercise in trained males.Eur J Appl Physiol2011;111:3007—16.

61.Hunter GR,Wetzstein CJ,M cLafferty Jr CL,Zuckerman PA, Landers KA,Bamman MM.High-resistance versus variable-resistance training in older adults.Med Sci Sports Exerc2001;33:1759—64.

62.Radaelli R,Botton CE,Wilhelm EN,Bottaro M,Lacerda F,Gaya A, et al.Low-and high-volume strength training induces sim ilar neuromuscular improvements in muscle quality in elderly women.Exp Gerontol2013;48:710—6.

63.Kraemer WJ,Ratamess NA,French DN.Resistance training for health and performance.Curr Sports Med Rep2002;1:165—71.

64.Kraemer WJ,Adams K,Cafarelli E,Dudley GA,Dooly C, Feigenbaum MS,et al.American College of Sports Medicine position stand.Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults.Med Sci Sports Exerc2002;34:364—80.

65.Ekkekakis P.Pleasure and displeasure from the body:perspectives from exercise.Cogn Emotion2003;17:213—39.

66.Ekkekakis P,Hall EE,Petruzzello SJ.Practical markers of the transition from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism during exercise:rationale and a case for affect-based exercise prescription.PrevMed2004;38:149—59.

67.Hall EE,Ekkekakis P,Petruzzello SJ.The affective benefi cence of vigorous exercise revisited.Br J Health Psych2002;7:47—66.

68.W illiams DM.Exercise,affect,and adherence:an integrated modeland a case for self-paced exercise.J Sport Exerc Psy2008;30:471—96.

69.W illiams DM,Dunsiger S,Ciccolo JT,Lew is BA,Albrecht AE, Marcus BH.Acute affective response to a moderate-intensity exercise stimulus predicts physical activity participation 6 and 12 months later.Psychol Sport Exerc2008;9:231—45.

70.Vukovich MD,Stubbs NB,Bohlken RM.Body composition in 70-yearold adults responds to dietary beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate similarly to that of young adults.J Nutr2001;131:2049—52.

71.Elsangedy HM,Krause MP,Krinski K,A lves RC,Hsin Nery Chao C,da Silva SG.Is the self-selected resistance exercise intensity by older women consistent with the American College of Sports Medicine guidelines to improve muscular fi tness?JStrengthCondRes2013;27:1877—84.

72.Storer TW,DolezalBA,Berenc M,Timm ins JE,Cooper CB.Effectof supervised,periodized exercise training versus self-directed training on lean body mass and other fi tness variables in health club members.J Strength Cond Res2014;28:1995—2006.

73.ElliottKJ,Sale C,Cable NT.Effects of resistance training and detraining on muscle strength and blood lipid profi les in postmenopausal women.Br J Sports Med2002;36:340—5.

74.Fahlman MM,Boardley D,LambertCP,Flynn MG.Effects of endurance training and resistance training on plasma lipoprotein profi les in elderly women.J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2002;57:B54—60.

75.Colado JC,Garcia-Masso X,Rogers ME,Tella V,Benavent J, Dantas EH.Effects of aquatic and dry land resistance training devices on body composition and physical capacity in postmenopausal women.J Hum Kinet2012;32:185—95.

76.Mazzeo RS,Cavanagh P,Evans WJ,Fiatarone M,Hagberg J, M cAuley E,etal.Exercise and physicalactivity forolderadults.Med Sci Sports Exerc1998;30:992—1008.

77.Hubleykozey CL,Wall JC,Hogan DB.Effects of a general exercise program on passive hip,knee,and ankle range of motion of older women.Top Geriatr Rehabil1995;10:33—44.

78.Frekany GA,Leslie DK.Effects of an exercise program on selected flexibility measurements of senior citizens.Gerontologist1975;15:182—3.

79.Lesser M.The effects of rhythmic exercise on the range of motion in older adults.Am Correct Ther J1978;32:118—22.

80.Bravo G,Gauthier P,Roy PM,Payette H,Gaulin P,Hervey M,et al. Impact of a 12-month exercise program on the physical and psychological health of osteopenic women.J Am Geriatr Soc1996;44:756—62.

81.Hopkins DR,Murrah B,Hoeger WWK,Rhodes RC.Effect of lowimpact aerobic dance on the functional fi tness of elderly women.Gerontologist1990;30:189—92.

82.Filho MLM,de Matos DG,Rodrigues BM,Aidar FJ,de Oliveira GR, Salgueiro RS,et al.The effects of 16 weeks of exercise on metabolic parameters,blood pressure,body mass index and functionalautonomy in elderly women.Int Sport Med J2013;14:86—93.

83.Simao R,Lemos A,Salles B,Leite T,Oliveira E,Rhea M,et al.The influence of strength,fl exibility,and simultaneous training on fl exibility and strength gains.J Strength Cond Res2011;25:1333—8.

84.Morey MC,Schenkman M,Studenski SA,Chandler JM,Crow ley GM, Sullivan Jr RJ,et al.Spinal-fl exibility-plus-aerobic versus aerobic-only training:effect of a random ized clinical trial on function in at-risk older adults.J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci1999;54:M 335—42.

85.LittMD,K leppinger A,Judge JO.Initiation and maintenance of exercise behavior in older women:predictors from the social learning model.J Behav Med2002;25:83—97.

86.King AC,Blair SN,Bild DE,Dishman RK,Dubbert PM,Marcus BH, etal.Determ inants of physical activity and interventions in adults.Med Sci Sports Exerc1992;24(Suppl.6):S221—36.

87.van der Bij AK,Laurant MG,Wensing M.Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for older adults:a review.Am J Prev Med2002;22:120—33.

88.Visek AJ,Olson EA,DiPietro L.Factors predicting adherence to 9 months of supervised exercise in healthy older women.J Phys Act Health2011;8:104—10.

89.Seguin RA,Economos CD,Palombo R,Hyatt R,Kuder J,Nelson ME. Strength training and older women:a cross-sectional study examining factors related to exercise adherence.J Aging Phys Act2010;18:201—18.

90.Brentano MA,Cadore EL,Da Silva EM,Ambrosini AB,Coertjens M, Petkow icz R,et al.Physiological adaptations to strength and circuit training in postmenopausalwomen w ith bone loss.J Strength Cond Res2008;22:1816—25.

91.Asikainen TM,M iilunpalo S,Kukkonen-Harjula K,Nenonen A, Pasanen M,Rinne M,et al.Walking trials in postmenopausal women: effectof low doses of exercise and exercise fractionization on coronary risk factors.Scand J Med Sci Sports2003;13:284—92.

92.Busby J,Notelovitz M,Putney K,Grow T.Exercise,high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol,and cardiorespiratory function in climacteric women.South Med J1985;78:769—73.

93.King AC,Haskell WL,Taylor CB,Kraemer HC,DeBusk RF.Group-vs. home-based exercise training in healthy older men and women.A community-based clinical trial.J Am Med Assoc1991;266:1535—42.

94.Ready AE,Naimark B,Ducas J,Sawatzky JV,Boreskie SL, Drinkwater DT,et al.Influence of walking volume on health benefi ts in women post-menopause.Med Sci Sports Exerc1996;28:1097—105.

95.Shinkai S,Watanabe S,Kurokawa Y,Torii J,Asai H,Shephard RJ. Effects of 12 weeks of aerobic exercise plus dietary restriction on body composition,resting energy expenditure and aerobic fi tness in m ildly obese middle-aged women.Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol1994;68:258—65.

96.Chow R,Harrison JE,Notarius C.Effect of two randomised exercise programmes on bone mass of healthy postmenopausalwomen.Br Med J1987;295:1441—4.

97.Irw in ML,Yasui Y,Ulrich CM,Bowen D,Rudolph RE,Schwartz RS, et al.Effect of exercise on total and intra-abdominal body fat in postmenopausal women:a random ized controlled trial.J Am Med Assoc2003;289:323—30.

98.Bemben DA,Fetters NL,Bemben MG,Nabavi N,Koh ET.Musculoskeletal responses to high-and low-intensity resistance training in early postmenopausal women.Med Sci Sports Exerc2000;32:1949—57.

99.Scanlon TC,Fragala MS,Stout JR,Emerson NS,Beyer KS,Oliveira LP, et al.Muscle architecture and strength:adaptations to short-term resistance training in older adults.Muscle Nerve2014;49:584—92.

100.Conceicao MS,Bonganha V,Vechin FC,de Barros Berton RP, Lixandrao ME,Nogueira FR,etal.Sixteen weeks of resistance training can decrease the risk of metabolic syndrome in healthy postmenopausal women.Clin Interv Aging2013;8:1221—8.

101.Balsamo S,Mota LM,Santana FS,Nascimento Dda C,Bezerra LM, Balsamo DO,et al.Resistance training versus weight-bearing aquatic exercise:a cross-sectional analysis of bone mineral density in postmenopausal women.Rev Bras Reumatol2013;53:193—8.

Received 22 October 2013;revised 29 January 2014;accepted 17 February 2014

*Corresponding author.

E-mail address:kkendall@georgiasouthern.edu(K.L.Kendall)

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport

2095-2546/$-see front matter CopyrightⒸ2014,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.A ll rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2014.02.001

CopyrightⒸ2014,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.A ll rights reserved.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2014年3期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2014年3期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Women’s health in exercise and aging:What do we know?

- Why women see differently from the way men see?A review of sex differences in cognition and sports

- Sex differences in exercise and drug addiction:A m ini review of animal studies

- Effects of carbohydrate supplements on exercise-induced menstrual dysfunction and ovarian subcellular structural changes in rats

- Exercise training and antioxidant supplementation independently improve cognitive function in adult male and female GFAP-APOE m ice

- Surgical menopause enhances hippocampal amyloidogenesis follow ing global cerebral ischem ia