Why women see differently from the way men see?A review of sex differences in cognition and sports

Rena Li

Center for Hormone Advanced Science and Education,Roskamp Institute,Sarasota,FL 34243,USA

Review

Why women see differently from the way men see?A review of sex differences in cognition and sports

Rena Li

Center for Hormone Advanced Science and Education,Roskamp Institute,Sarasota,FL 34243,USA

The differences of learning and memory between males and females have been well documented and confi rmed by both human and animal studies.The sex differences in cognition started from early stage of neuronaldevelopmentand last through entire lifespan.The major biological basis of the gender-dependent cognitive activity includes two major components:sex hormone and sex-related characteristics,such as sexdetermining region of the Y chromosome(SRY)protein.However,the know ledge of how much biology of sex contributes to normal cognitive function and elite athletes in various sports are still pretty lim ited.In this review,we w illbe focusing on sex differences in spatial learning and memory—especially the role of male-and female-type cognitive behaviors in sports.

Brain;Hormones;Learning and memory in sports;Sex-specifi c cognition

1.Introduction

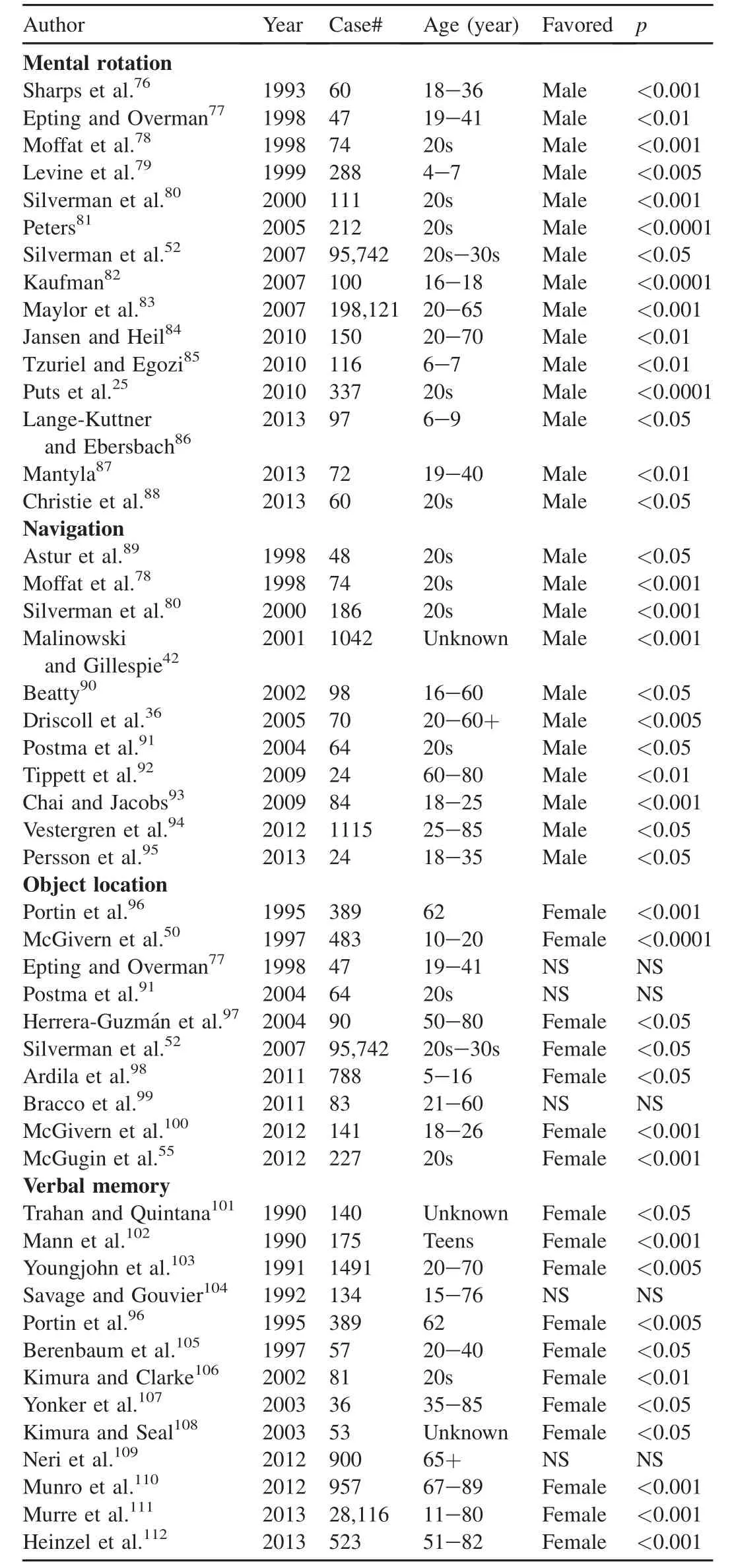

Differing performances between the sexes have been observed on a number of common learning tasks in both human and animal literature.There are four classes ofmemory tasks for which sex differences have been frequently reported: spatial,verbal,autobiographical,and emotional memory. Typically,ithas been commonly believed thatmales show an advantage on spatial tasks,and females on verbal tasks. However,evidence now shows that the male spatialadvantage does not apply to certain spatial tasks.Female advantage in verbal processing extends into many memory tasks which are not explicitly verbal.1In this session of review,we included studies of human spatial ability and verbalmemory w ith sexfavored components(Table 1).

2.Typical male-favored spatial cognitive behaviors

2.1.Mental rotation

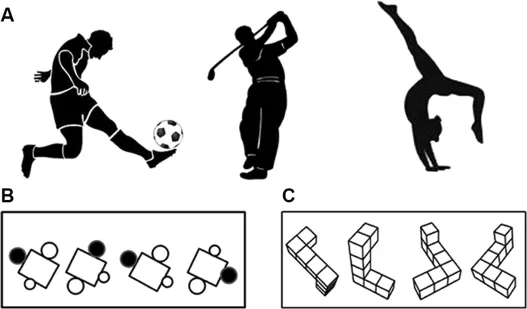

The concept of mental rotation(spatial rotation)as a cognitive behavior was introduced by Shepard and Metzler2in 1971.It requires the dynam ic spatial transformation of objects w ith respect to their internal spatial structure.Furthermore, mental rotation is involved in problem solving,3acquiring mathematical know ledge,4and academic thinking.5Studies using eye movement measurements,direct recording from electrodes implanted in the brain,functional magnetic resonance imaging(fMRI),and transcranial magnetic stimulation suggested that mental rotation involves motor and visual processes and related brain regions.6The typical testofmental rotation involves distinguishing a shape or an object that has been rotated from a sim ilar,rotated shape or object,often a m irror image.There are simple(2-dimensional stimuli)and complex(3-dimensionalstimuli)tasks as shown in Fig.1.The rotation of simple 2-dimensional stimuli can lead to greater activation of the leftparietalarea of brain rather than the right parietal area,while the complex 3-dimensional rotations are associated w ith more right parietalactivation than leftparietalactivation.7Studies showed that the analogy between physical and mentalprocesses requires activation of parietalarea which is linked to angle of rotation.8Research on the early developmentappears that the mental rotation may appearas early as 4 months of age,9,10and reach near-adult levelaround the age of 6—7 years.11,12

Table 1 Sex differences in spatial learning and memory.

2.1.1.Sex differences in mental rotation

Mental rotation has greatsex differences,particularly males usually perform better on mental rotation tasks than do females.13However,the sex differences in mental rotation only appear in adults.7Interestingly,sex differences in mental rotation are also confi rmed by brain imaging studies that showed different networks activating during mental rotation tasks for men and women,such as increased activation in the parietal lobules in men,and increased activity in frontalareas in women.14—16The unique brain regional activities between males and females may be interpreted as evidence of a different cognitive strategy between men and women to solve mental rotation problems.While it is unclear whether the sex difference in mental rotation is regulated or dependent on sex steroids,some studies showed that sex hormones play direct role in mental rotation.For example,in females,low estradiol during normal menstrual cycle was found to be associated w ith significantly better accuracy on the mental rotation task w ith large angles of rotation by 2-dimensional object,while estrogen showed no effects on small angles of rotation.17In contrast to estrogen,testosterone showed closely positive linkage to mental rotation.A recent study of women w ith polycystic ovary syndrome(PCOS),a disease characterized by elevated testosterone levels,showed a much better score in mental rotation task in women w ith PCOS compared to gender-matched normal controls.18Furthermore,w ithin the PCOS group,the circulating levels of testosterone were significantly positively correlated w ith 3-dimensional scoring, whereas estradiol was significantly negatively correlated w ith 3-dimensional scoring.Furthermore,Aleman et al.19found that a single administration of testosterone in young women improved performance in a 3-dementia spatial rotation task. However,the relationship between testosterone levels and mental rotation in males are controversial.For instance, mental rotation was impaired in men w ith hypergonadotropic hypogonadism(androgen deficiency)compared to normal healthy male controls,20men w ith higher free testosterone levels performed better in mental rotation compared to control subjects,21and higher levels of salivary testosterone were associated w ith lower error rates and faster responses in mental rotation tests in young male adults,22suggesting mental rotation performance is positively related to testosterone levels in men.On the other hand,a study of 308 male tw ins showed that testosterone levels at age 14(puberty)are significantly related to poor performance in mental rotation test in male young adults at age 21—23.23The negative relationship between testosterone levels and mental rotation performance is also reported in oldermales as higher testosterone levels correlated w ith poorer performance.24Furthermore,a study of salivary testosterone levels in 160 women and 177 men showed that circadian changes in testosterone were unrelated to changes in spatial performance in either sex.25Furthermore,the effects of sex hormones on mental rotation have also been investigated in people w ith transsexalism which individuals seek cross-gender treatment to change their sex.Studies found that untreated male-to-female transsexuals had better performance on 3-dimensional spatial rotation taskthan untreated female-to-male transsexuals but after 10 months of treatment the differences were reversed.26However, later studies of cross-sex hormone treatment showed no change in the sex-sensitive mental rotation ability,27particularly,no change in spatial abilities in male-to-female transsexuals under estrogen treatment.28It is worth to notice that the controversial findings of the effects of sex hormones on mental rotation may be well associated with whether the studies were done in subjects with physiological or pathological conditions,as well as at young or old ages.

Fig.1.Mental rotation associated with sports.Soccer,golf,and gymnastics(A)require spatial rotation.The tasks include simple 2-dimensional stimuli(B)or complex 3-dimensionalstimuli(C).In tests,two ormore objects which were either identicalormirror images ofeach otherwere placed atdifferentorientation in space w ith varying degrees of angular disparity.

2.1.2.Mental rotation in sports

Mental rotation tasks are broadly characterized as exercises and sports that require the mental repositioning of a 2-or 3-dimensional object.The mental rotation information is constantly used in sports in order to locate partners or opponents(team sports),identify the target location(shooting, golf),using landmarkers in space(gymnastics).29,30In general, athletes exhibit differences in perceptual-cognitive abilities when compared to non-athletes.For example,gymnasts outperformed non-athletes in mental rotation task and in general better for pictures of human figures than for pictures of cubed figures,31suggesting variants of differentmental rotation tasks should be applied in testing athletes,since they may have differentoutcomes depending on athletes’type of sport and/or the type of sport that is reflected in the mental rotation stimuli. Although mental rotation is developed at early stage during neuronal development period and the differences of mental rotation between athletes and non-athletes m ight be related to the subjects w ith better spatial ability,studies showed that the mental rotation is trainable for better.Therefore,this would be beneficial for our understanding of motor learning based on mental simulation and could contribute to the training of athletes from sports such as gymnastics,soccer,golf,and more for skydiving,scuba-diving,and climbing,where losses of spatial orientation can be life-threatening.32Exercises also have positive impact on mental rotation.A study of juggling training showed that 3 months of juggling training improved performance on a chronometric mental rotation task w ith cube figures,compared to a controlgroup which did not receive any training.33

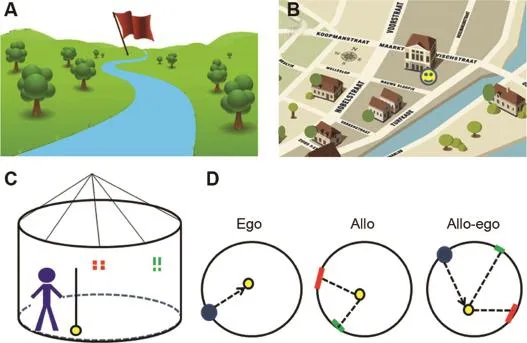

2.2.Spatial navigation

Navigation tests,also called a way-finding,are commonly conducted by having subjects reconstructa path through a map or real space.There are two different approaches that may be involved:egocentric and allocentric strategies(Fig.2).An egocentric strategy involves more local landmarks and directional cues as personal directions.An allocentric strategy uses the absolute position of general landmarks,such as distance, as absolute directions.34Individuals w ith hippocampal sclerosis were more impaired in navigating through a virtualmaze in which learning was associated w ith egocentric memory.The allocentric memory impairment is found in patients w ith extensive hippocampalsclerosis plus subcortical deterioration, suggesting a combination of hippocampaland corticaldamage is associated w ith negative changes in allocentric memory.35Patients with temporal lobe epilepsy w ithout hippocampal sclerosis do not display cognitive deficits of allocentric or egocentric memory.

2.2.1.Sex differences in spatial navigation

Fig.2.Spatialnavigation tests.There are virtualpark(A)or virtualmaze(B)tests as a determ inantof capability in allocentric(allo)and egocentric(ego)memory, respectively.A hidden goal task is also commonly used.(C)Scheme of the individualsubject in a realenvironment.(D)Navigation to a goal(small yellow circle) by the starting position(blue circle)as ego subject,orby the relation to two landmarkers(red and green lines)as in the allo subject,orby both starting position and landmarkers as allo-ego subject.

A lthough males perform better than females in the navigation strategy,the relationship between navigation and one’s level of testosterone has not been consistently demonstrated.36,37It is known that men tend to favor a more allocentric strategy(accurate judgmentsof distance),while women are more frequently egocentric(able to recallmore streetnames and building shapes as landmarks)navigators.38,39However,it is worth pointing out that the outcome of sex-specific navigation test is closely related to the experimental conditions.For example,when test was performed w ithin a single room or w ithin an indoor environment without absolute directional cues,men and women perform the same.40,41On the otherhand, men significantly outperform women in navigating through a large outdoor space.42Recent human studies using a computerized water maze to m irror rodent tests of object recognition and spatial navigation test showed a faster and more efficient performance by college-aged malescompared to femalesof the same age.42Studies also reported that older adults’spatial navigation learning were preferentially related to processing of landmark information,whereas processing of boundary information played a more prom inent role in younger adults.43Efficient spatial navigation requires not only accurate spatial know ledge but also the selection of appropriate strategies. Successfulperformance using an allocentric place strategy was observed in young participants,while older participants were able to recall the route when approaching intersections from the same direction as during encoding and failed to use the correct strategy when approaching intersections from new directions.44Aging specifically impairssw itching navigationalstrategy to an allocentric navigationalstrategy.Indeed,a new walking spatial navigation testhas been recently developed for early detection of cognitive impairment in an aging population.45

2.2.2.Spatial navigation in sports

Athletes often give more accurate estimates of egocentric distance along the ground than do non-athletes,particularly in the sports taking place in highly standardized spatial settings, such as basketball and baseball.There is some evidence that golfers are much more accurate than others in estimating distances on grass.46A study ofspatialnavigation differences in female athletes and non-athletes showed that the elite athletes, such as soccer,field hockey,and basketball,had fasterwalking times during the navigation of all obstructed environments by processing visuo-spatial information faster and navigating through complex,novelenvironments atgreater speeds.47

3.Typical fem ale-favored m em ory

3.1.Object location or recognition memory

Object location is designed by presenting differentarrays of common objects between the training phases.The test requires participants to identify the difference between the two selections.In human studies,the medial temporal lobe and perirhinal cortex are impaired in various types of object location tasks,but only when the objects have a high number of overlapping features.Meanwhile,patients w ith medial temporal lesions that are confined to the hippocampus showed normal performance on object location tasks regardless of the level of feature ambiguity.48,49Significant female advantages have been observed in several studies of object location memory.50—52This is opposed to mental rotation and navigation tasks,suggesting that object location differs from other spatial tasks in terms of its cognitive demands.

3.1.1.Sex differences in object recognition

Females apparently outperform males in object location tasks.When geometric and non-geometric objects are both available for specifying location,men have been shown to rely more heavily on geometry compared to women and the sex differences in object location were also reported in youngchildren w ith boys relied more heavily than girls on geometry to guide localization.53Sex differences in the object recognition memory are also related to the type of objects.For example,studies found thatmen are usually more affective by plants whereas women are more sensitive with animals.54The object differences between males and females are further confi rmed w ith recent studies that demonstrated an advantage for living categories in women while men showed an advantage for cars.55Moreover,a study of spatial object location memory using abstract design showed no sex differences in either the visual or spatial location tests.56All together,evidence suggests that stereotypical interests may play a role in these effects.

3.1.2.Spatial object location in sports

Object location or recognition is closely related to sports w ith gaze characterization,such as elite shotgun shooting.One study recorded point of gaze and gun barrel kinematics in groups of elite(n=24)and sub-elite(n=24)shooters participating in skeet,trap,and double trap events.They reported that in skeet,trap,and double trap disciplines,elite shooters demonstrated both an earlier onset and a longer relative duration of quieteye than their sub-elite counterparts did,suggesting a longer quieteye duration m ightbe critical to a successful performance in all three shotgun disciplines.57Another sport is cricket which requires interception of a fast moving object,cricket ball.A recent study showed that elite cricket batsmen experienced no decrease in performance levels when hitting cricket balls delivered to them at approximately 30 m/s even when foveal vision was temporarily impaired by wearing contact lenses to induce myopic blur.58Depending on the spatio-temporal demands of the task and the intentions of the batsman a range of visual search strategies can be employed to support their actions.

3.2.Verbal memory

Two kinds of general measures of verbal memory have been used in most studies to identify sex differences.One is the Controlled Oral Word Association Test(COWAT)to test verbal fluency and another is the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test(RAVLT),also known as the California Verbal Learning Test(CVLT),which has participants recall a list of words.

3.2.1.Sex differences in verbal memory

Women outperform men in both measures.Interestingly, the female advantage in verbal memory is consistent throughout the lifespan,59,60suggesting circulating sex hormone independency.Women generally score higher than men on verbal memory tasks,possibly because women tend to use semantic clustering in recall.Studies showed that the sex differences in recall and semantic clustering in the verbal learning test diminished w ith a shorter word list in a relative smallsample study.61A 10-year longitudinalstudy ofover600 nondemented adults,aged 35—80 years,found stable sex differences across five age groups—women outperformed men on verbal memory,verbal recognition,and semantic fluency tasks,while men demonstrated better visuospatial ability.62Some studies showed that healthy elderly women have better immediate word learning,63verbal memory,and episodic memory compared to age-matched men.64However,a recent meta-analysis ofneurocognitive data from 15 studies(n=828 men;1238 women)showed that men modestly but significantly outperformed women in all of the cognitive domains been exam ined,including verbal and visuospatial tasks and tests of episodic and semantic memory,while age and minimental state examination(MMSE)were not associated w ith the male-advance in memory.65Some also reported better visual memory,66working memory,67and episodic memory67in elderly men than women.Furthermore,others have also reported no sex differences in the elderly forverbalmemory.68So,there exists no clear pattern of sex advantages formemory in the healthy elderly,and any sex differences appear to be task dependent.A cross-sectional analysis of the association between sex hormones,metabolic parameters,and psychiatric diagnoses w ith verbal memory in healthy aged men showed that higher levels of serum sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG)were associated with a worse verbal memory,69suggesting levels of free testosterone influence male verbal memory.However,findings of sex differences in verbal memory in young adults orearly adolescentsare contradictory. Studies showed no association between the sex-dependent verbal memory and age,level of sex hormone,or puberty development in teenage boys and girls.70Furthermore,a recentstudy including 366 women and 330 men aged between 16 and 69 years of age,showed thatwomen outperformed men on auditory memory tasks due to female advancement in verbal memory,whereas male adolescents and older male adults showed higher level performances on visual episodic and visual working memory measures.71

3.2.2.Verbal memory in sports

While there are no sports specific involved or not involved verbal memory,extensive studies showed sex differences on concussion outcomes between concussed male and female athletes,such as female concussed athletes have been reported to have greater neurocognitive impairments on reaction time and visual memory when compared w ith male concussed athletes.72,73However,it is unknown whether the sex differences in cognitive impairment induced by concussion in male and female athletes are associated w ith the male sports (football)which lacking of female players.A recent study included female and male concussed soccer players and found a significant between-patient main effect for sex on verbal memory,such as female athletes scored lower than male athletes.74While there is no know ledge of what causes the sex differences in verbal memory impairment between concussed male and female athletes,a recent study showed that shorter and intermediate sleep duration after concussion is associated w ith the lower score of verbalmemory,and female concussed athletes often reported more symptoms of fatigue,headache, and sleep difficulties.75

4.Conclusion

The differences in learning and memory between men and women are commonly recognized by general population as well as scientists.Males outperform females in spatialmental rotation and navigation tasks,while females often do betteron object location or recognition as wellas verbal memory tasks. A lthough it is known that the gender differences in the cognition started from early development stage and last throughout whole lifespans,recent studies of people w ith transsexalism and elite athletes demonstrated thatsex hormone treatment and exercised might be able to alter the sterol sextype cognition.In addition,it is worth to notice that many neurological diseases exhibit sex differences,such as women having a higher prevalence of A lzheimer’s disease,a most common form of dementia in elderly than age-matched men. We believe that better understanding the biology of sex differences in cognitive function w ill not only provide insight into healthy life style,promoting gender-specific exercise or sports,but also is integral to the developmentof personalized, gender-specific medicine.

Acknow ledgm ent

This work was supported by the American Health Assistance Foundation(G2006-118),and the National Institutes of Health(R01AG032441—01 and R01AG025888).

1.Andreano M,Cahill L.Sex infl uences on the neurobiology of learning and memory.Learn Mem2009;16:248—66.

2.Shepard R,Metzler J.Mental rotation of three-dimensional objects.Science1971;171:701—3.

3.Geary DC,Saults SJ,Liu F,Hoard MK.Sex differences in spatial cognition,computational fluency,and arithmetical reasoning.J Exp Child Psychol2000;77:337—53.

4.Hegarty M,Kozhevnikov M.Types of visual-spatial representations and mathematical problem solving.J Educ Psychol1999;91:684—9.

5.Peters M,Chisholm P,Laeng B.Spatial ability,student gender,and academ ic performance.J Educ Psychol1995;84:60—73.

6.Harris J,Hirsh-Pasek K,Newcombe NS.Understanding spatial transformations:sim ilarities and differences between mental rotation and mental folding.Cogn Process2013;14:105—15.

7.Roberts JE,Bell MA.Sex differences on a mental rotation task:variations in electroencephalogram hem ispheric activation between children and college students.Dev Neuropsychol2000;17:199—223.

8.Zacks JM.Neuorimaging studies ofmental rotation:a meta-analysis and review.J Cogn Neurosci2008;20:1—19.

9.Moore DS,Johnson SP.Mental rotation in human infants:a sex difference.Psychol Sci2008;19:1063—6.

10.Quinn PC,Liben LS.A sex difference in mental rotation in young infants.Psychol Sci2008;19:1067—70.

11.Dean AL,Duhe DA,Green DA.The development of children’s mental tracking strategies on a rotation task.JExpChildPsychol1983;36:226—40.

12.Piaget J,Inhelder B.Mental imagery in the child:a study of the development of imaginal representation(P.A.Chilton,Trans.).New York: Basic Books;1971.

13.Li R,Singh M.Sex differences in cognitive impairmentand A lzheimer’s disease.Front Neuroendocrinol2014;35:385—403.

14.Hugdahl K,Thomsen T,Ersland L.Sex differences in visuospatial processing:an fMRI study of mental rotation.Neuropsychologia2006;44:1575—83.

15.Seurinck R,Vingerhoets G,de Lange FP,Achten E.Does egocentricmental rotation elicit sex differences?NeuroImage2004;23:1440—9. 16.Gizewski ER,Krause E,Wanke I,Forsting M,Senf W.Gender-specifi c cerebral activation during cognitive tasks using functional MRI:comparison of women in m id-luteal phase and men.Neuroradiology2006;48:14—20.

17.Hampson E,Levy-Cooperman N,Korman JM.Estradiol and mental rotation:relation to dimensionality,difficulty,orangular disparity?Horm Behav2014;65:238—48.

18.Barry JA,Parekh HS,Hardiman PJ.Visual-spatial cognition in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome:the role of androgens.Hum Reprod2013;28:2832—7.

19.Aleman A,Bronk E,Kessels RPC,Koppeschaar HPF,van Honk J.A single adm inistration of testosterone improves visuospatial ability in young women.Psychoneuroendocrinology2004;29:612—7.

20.Hier DB,Crow ley Jr WF.Spatial ability in androgen-deficient men.N Engl J Med1982;306:1202—5.

21.Hausmann M,Schoofs D,Rosenthal HE,Jordan K.Interactive effects of sex hormones and gender stereotypes on cognitive sex differences—a psychobiosocial approach.Psychoneuroendocrinology2009;34:389—401.

22.Hooven CK,Chabris CF,Ellison PT,Kosslyn SM.The relationship of male testosterone to components of mental rotation.Neuropsychologia2004;42:782—90.

23.Vuoksimaa E,Kaprio J,Eriksson CJ,Rose RJ.Pubertal testosterone predicts mental rotation performance of young adult males.Psychoneuroendocrinology2012;37:1791—800.

24.Martin DM,W ittert G,Burns NR,M cPherson J.Endogenous testosterone levels,mental rotation performance,and constituent abilities in m iddle-to-older aged men.Horm Behav2008;53:431—41.

25.Puts DA,Ca´rdenas RA,Bailey DH,Burriss RP,Jordan CL, Breedlove SM.Salivary testosterone does not predict mental rotation performance in men or women.Horm Behav2010;58:282—9.

26.Slabbekoorn D,Van Goozen SHM,Megens J,Gooren LJG,Cohen-Kettenis PT.Activating effects of cross-sex hormones on cognitive functioning:a study of short-term and long-term hormone effects in transsexuals.Psychoneuroendocrinology1999;24:423—47.

27.Haraldsen IR,Egeland T,Haug E,Finset A,Opjorsdsmoen S.Cross-sex hormone treatment does not change sex-sensitive cognitive performance in gender identity disorder patients.Psychiatr Res2005;137:161—74.

28.M iles C,Green R,Hines M.Estrogen effects on cognition,memory and mood in male-to-female transsexuals.Horm Behav2006;50:707—8.

29.Ozel S,Larue J,Molinaro C.Relation between sportactivity and mental rotation:comparison of three groups of subjects.Percept Mot Skills2002;95:1141—54.

30.Jansen P,Lehmann J,Van Doren J.Mental rotation performance in male soccer players.PLoS One2012;7:e48620.http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0048620.

31.Jansen P,Lehmann J.Mental rotation performance in soccer players and gymnasts in an object-based mental rotation task.Adv Cogn Psychol2013;2:92—8.

32.Heinen T.Does the athletes’body shape the athletes’m ind?A few ideas on athletes’mental rotation performance.Commentary on Jansen and Lehmann.Adv Cogn Psychol2013;9:99—101.

33.Jansen P,Titze C,Heil M.The infl uence of juggling on mental rotation performance.Int J Sport Psychol2009;40:351—9.

34.Maguire EA,Burgess N,O’Keefe J.Human spatialnavigation:cognitive maps,sexual dimorphism,and neural substrates.Curr Opin Neurobiol1999;9:171—7.

35.Weniger G,Ruhleder M,Lange C,Irle E.Impaired egocentric memory and reduced somatosensory cortex size in temporal lobe epilepsy w ith hippocampal sclerosis.Behav Brain Res2012;227:116—24.

36.Driscoll I,Hamilton DA,Yeo RA,Brooks WM,Sutherland RJ.Virtual navigation in humans:the impact of age,sex,and hormones on place learning.Horm Behav2005;47:326—35.

37.Burkitt J,W idman D,Saucier DM.Evidence for the infl uence of testosterone in the performance of spatial navigation in a virtual water maze in women but not in men.Horm Behav2007;51:649—54.

38.Dabbs Jr JM,Chang E-L,Strong RA,M ilun R.Spatialability,navigation strategy,and geographic know ledge among men and women.Evol Hum Behav1998;19:89—98.

39.Galea LAM,Kimura D.Sex differences in route-learning.Pers Indiv Differ1993;14:53—65.

40.Lew in C,Wolgers G,Herlitz A.Sex differences favoring women in verbal but not in visuospatial episodic memory.Neuropsychology2001;15:165—73.

41.Law ton CA,Charleston SI,Zieles AS.Individual-and gender-related differences in indoor wayfinding.Environ Behav1996;28:204—19.

42.Malinowski JC,Gillespie WT.Individual differences in performance on a large-scale, real-world wayfinding task.JEnvironPsychol2001;21:73—82.

43.Schuck NW,Doeller CF,Schjeide BM,Schro¨der J,Frensch PA, Bertram L,et al.Aging and KIBRA/WWC1 genotype affect spatial memory processes in a virtual navigation task.Hippocampus2013;23:919—30.

44.Wiener JM,de Condappa O,Harris MA,Wolbers T.Maladaptive bias for extrahippocampal navigation strategies in aging humans.J Neurosci2013;33:6012—7.

45.Perrochon A,Kemoun G,Watelain E,Berthoz A.Walking stroop carpet: an innovative dual-task concept for detecting cognitive impairment.Clin Interv Aging2013;8:317—28.

46.Durgin FH,Li Z.Perceptualscale expansion:an effi cientangular coding strategy for locomotor space.AttenPerceptPsychophys2011;73:1856—70.

47.Ge´rin-Lajoie M,Ronsky JL,Loitz-Ramage B,Robu I,Richards CL, M cFadyen BJ.Navigationalstrategies during fastwalking:a comparison between trained athletes and non-athletes.GaitPosture2007;26:539—45. 48.Barense MD,Bussey TJ,Lee AC,Rogers TT,Davies RR,Saksida LM, et al.Functional specialization in the human medial temporal lobe.J Neurosci2005;25:10239—46.

49.Lee AC,Rudebeck SR.Investigating the interaction between spatial perception and working memory in the human medial temporal lobe.J Cogn Neurosci2010;22:2823—35.

50.M cGivern RF,Huston JP,Byrd D,King T,Siegle GJ,Reilly J.Sex differences in visual recognition memory:support for a sex-related difference in attention in adults and children.BrainCogn1997;34:323—36.

51.Levy LJ,Astur RS,Frick KM.Men and women differ in objectmemory but not performance of a virtual radial maze.Behav Neurosci2005;119:853—62.

52.Silverman I,Choi J,Peters M.The hunter-gatherer theory of sex differences in spatial abilities:data from 40 countries.Arch Sex Behav2007;36:261—8.

53.Lourenco SF,Addy D,Huttenlocher J,Fabian L.Early sex differences in weighting geometric cues.Dev Sci2011;14:1365—78.

54.Gainotti G.The influence of gender and lesion location on nam ing disorders for animals, plants and artefacts.Neuropsychologia2005;43:1633—44.

55.M cGugin RW,Richler JJ,Herzmann G,Speegle M,Gauthier I.The vanderbiltexpertise test reveals domain-general and domain-specific sex effects in object recognition.Vis Res2012;69:10—22.

56.Rahman Q,Bakare M,Serinsu C.No sex differences in spatial location memory for abstract designs.Brain Cogn2011;76:15—9.

57.Causer J,Bennett SJ,Holmes PS,Janelle CM,Williams AM.Quieteye duration and gun motion in elite shotgun shooting.Med Sci Sports Exerc2010;42:1599—608.

58.Mann DL,Ho NY,De Souza NJ,Watson DR,Taylor SJ.Is optimal vision required for the successfulexecution of an interceptive task?Hum Mov Sci2007;26:343—56.

59.Gale SD,Baxter L,Connor DJ,Herring A,Comer J.Sex differences on the Rey auditory verbal learning test and the brief visuospatial memory test-revised in the elderly:normative data in 172 participants.J Clin Exp Neuropsychol2007;29:561—7.

60.Rodriguez-Aranda C,Martinussen M.Age-related differences in performance of phonem ic verbal fluency measured by Controlled OralWord Association Task(COWAT):a meta-analytic study.Dev Neuropsychol2006;30:697—717.

61.Sunderaraman P,Blumen HM,Dematteo D,Apa ZL,Cosentino S.Task demand influences relationships among sex,clustering strategy,and recall:16-word versus 9-word list learning tests.Cogn Behav Neurol2013;26:78—84.

62.de Frias CM,Nilsson LG,Herlitz A.Sex differences in cognition are stable over a 10-year period in adulthood and old age.Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn2006;13:574—87.

63.van Hooren SA,Valentijn AM,Bosma H,Ponds RW,van Boxtel MP, Jolles J.Cognitive functioning in healthy older adults aged 64—81:a cohort study into the effects of age,sex,and education.Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn2007;14:40—54.

64.Gerstorf D,Herlitz A,Smith J.Stability of sex differences in cognition in advanced old age:the role of education and attrition.J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci2006;61:245—9.

65.Irvine K,Laws KR,Gale TM,Kondel TK.Greater cognitive deterioration in women than men w ith A lzheimer’s disease:a meta analysis.J Clin Exp Neuropsychol2012;34:989—98.

66.Proust-Lima C,Amieva H,Letenneur L,Orgogozo JM,Jacqmin-Gadda H,Dartigues JF.Gender and education impact on brain aging:a general cognitive factor approach.Psychol Aging2008;23:608—20.

67.Read S,Pedersen NL,Gatz M,Berg S,Vuoksimaa E,Malmbert B,etal. Sex differences afterall those years?Heritability of cognitive abilities in old age.J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci2006;61:137—43.

68.Parsons TD,Rizzo AR,van der Zaag C,McGee JS,Buckwalter JG. Gender differences and cognition among older adults.Aging Neuropsychol Cogn2005;12:78—88.

69.Takayanagi Y,Spira AP,M cIntyre RS,Eaton WW.Sex hormone binding globulin and verbal memory in older men.Am J Geriatr Psychiatry; 2013.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2013.02.003 [Epub ahead of print].

70.Herlitz A,Reuterskio¨ld L,Love´n J,Thilers PP,Rehnman J.Cognitive sex differences are not magnified as a function of age,sex hormones,or puberty development during early adolescence.Dev Neuropsychol2013;38:167—79.

71.Pauls F,Petermann F,Lepach AC.Gender differences in episodic memory and visual working memory including the effects of age.Memory2013;21:857—74.

72.Broshek DK,Kaushik T,Freeman JR,Erlanger D,Webbe F,Barth JT. Sex differences in outcome follow ing sports-related concussion.J Neurosurg2005;102:856—63.

73.Colvin A,Mullen J,Lovell M,West R,Collins M,Groh M.The role of concussion history and gender in recovery from soccer-related concussion.Am J Sports Med2009;37:1699—704.

74.Covassin T,Elbin RJ,Bleecker A,Lipchik A,Kontos AP.Are there differences in neurocognitive function and symptoms between male and female soccer players after concussions?AmJSportsMed2013;41:2890—5.

75.M cClure DJ,Zuckerman SL,Kutscher SJ,Gregory AJ,Solomon GS. Baseline neurocognitive testing in sports-related concussions:the importance of a prior night’s sleep.Am J Sports Med2014;42:472—8.

76.Sharps M J,Welton AL,Price JL.Genderand task in the determ ination of spatial cognitive performance.Psychol Women Q1993;17:71—83.

77.Epting LK,Overman WH.Sex sensitive tasks in men and women:a search for performance fluctuations across the menstrual cycle.Behav Neurosci1998;112:1304—17.

78.Moffat SD,Hampson E,Hatzipantelis M.Navigation in a“virtual”maze:sex differences and correlation w ith psychometric measures of spatial ability in humans.Evol Hum Behav1998;19:73—87.

79.Levine SC,Huttenlocher J,Taylor A,Langrock A.Early sex differences in spatial skill.Dev Psychol1999;35:940—9.

80.Silverman I,Choi J,Mackewn A,Fisher M,Moro J,Olshansky E. Evolved mechanisms underlying wayfinding.Further studies on the hunter-gatherer theory of spatial sex differences.Evol Hum Behav2000;21:201—13.

81.Peters M.Sex differences and the factor of time in solving Vandenberg and Kuse mental rotation problems.Brain Cogn2005;57:176—84.

82.Kaufman SB.Sex differences in mental rotation and spatialvisualization ability:can they be accounted for by differences in working memory capacity?Inteligence2007;35:211—23.

83.Maylor EA,Reimers S,Choi J,Collaer ML,Peters M,Silverman I. Gender and sexual orientation differences in cognition across adulthood: age is kinder to women than to men regardless of sexualorientation.Arch Sex Behav2007;36:235—49.

84.Jansen P,Heil M.Gender differences in mental rotation across adulthood.Exp Aging Res2010;36:94—104.

85.Tzuriel D,Egozi G.Gender differences in spatial ability of young children:the effects of training and processing strategies.Child Dev2010;81:1417—30.

86.Lange-Ku¨ttner C,Ebersbach M.Girls in detail,boys in shape:gender differences when drawing cubes in depth.BrJPsychol2013;104:413—37.

87.Mantyla T.Gender differences in multitasking reflect spatial ability.Psychol Sci2013;24:514—20.

88.Christie GJ,Cook CM,Ward BJ,Tata MS,Sutherland J,Sutherland RJ, et al.Mental rotational ability is correlated with spatial but not verbal working memory performance and P300 amplitude in males.PLoS One2013;8:e57390.http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0057390.

89.Astur RS,Ortiz ML,Sutherland RJ.A characterization of performance by men and women in a virtualMorris water task:a large and reliable sex difference.Behav Brain Res1998;93:185—90.

90.Beatty WW.Sex difference in geographical know ledge:driving experience is not essential.J Int Neuropsychol Soc2002;8:804—10.

91.Postma A,Jager G,Kessels RPC,Koppeschaar HPF,van Honk J.Sex differences for selective forms of spatial memory.BrainCogn2004;54:24—34.

92.Tippett WJ,Lee JH,M raz R,Zakzanis KK,Snyder PJ,Black SE,et al. Convergent validity and sex differences in healthy elderly adults for performance on 3D virtual reality navigation learning and 2D hidden maze tasks.Cyberpsychol Behav2009;12:169—74.

93.Chai XJ,Jacobs LF.Sex differences in directional cue use in a virtual landscape.Behav Neurosci2009;123:276—83.

94.Vestergren P,Ro¨nnlund M,Nyberg L,Nilsson LG.Multigroup confi rmatory factor analysis of the cognitive dysfunction questionnaire:instrument refinement and measurement invariance across age and sex.Scand J Psychol2012;53:390—400.

95.Persson J,Herlitz A,Engman J,Morell A,Sjo¨lie D,W ikstro¨m J,et al. Remembering our origin:gender differences in spatial memory are reflected in gender differences in hippocampal lateralization.Behav Brain Res2013;256:219—28.

96.Portin R,Saarijarvi S,Joukamaa M,Salokangas RK.Education,gender and cognitive performance in a 62-year-old normal population:results from the Turva Project.Psychol Med1995;25:1295—8.

97.Herrera-Guzma´n I,Pen˜a-Casanova J,Lara JP,Gudayol-Ferre´E,Bo¨hm P. Infl uence of age,sex,and education on the visual object and space perception battery(VOSP)in a healthy normal elderly population.Clin Neuropsychol2004;18:385—94.

98.Ardila A,Rosselli M,Matute E,Inozem tseva O.Gender differences in cognitive development.Dev Psychol2011;47:984—90.

99.Bracco L,Bessi V,Alari F,Sforza A,Barilaro A,Marinoni M.Cerebral hemodynam ic lateralization during memory tasks as assessed by functional transcranial doppler(fTCD)sonography:effects of gender and healthy aging.Cortex2011;47:750—8.

100.M cGivern RF,Adams B,Handa RJ,Pineda JA.Men and women exhibit a differential bias for processing movement versus objects.PLoS One2012;7:e32238.http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0032238.

101.Trahan DE,Quintana JW.Analysis of gender effects upon verbal and visual memory performance in adults.ArchClinNeuropsychol1990;5:325—34.

102.Mann VA,Sasanuma S,Sakuma N,Masaki S.Sex differences in cognitive abilities:a cross-cultural perspective.Neuropsychologia1990;28:1063—77.

103.Youngjohn JR,Larrabee GJ,Crook III TH.First-last names and the grocery list selective rem inding test:two computerized measures of everyday verbal learning.Arch Clin Neuropsychol1991;6:287—300.

104.Savage RM,Gouvier WD.Rey auditory—verbal learning test:the effects of age and gender,and norms for delayed recall and story recognition trials.Arch Clin Neuropsychol1992;7:407—14.

105.Berenbaum SA,Baxter L,Seidenberg M,Hermann B.Role of the hippocampus in sex differences in verbal memory:memory outcome follow ing left anterior temporal lobectomy.Neuropsychology1997;11:585—91.

106.Kimura D,Clarke PG.Women’s advantage on verbal memory is not restricted to concrete words.Psychol Rep2002;91:1137—42.

107.Yonker JE,Eriksson E,Nilsson LG,Herlitz A.Sex differences in episodic memory:m inimal influence of estradiol.BrainCogn2003;52:231—8.

108.Kimura D,Seal BN.Sex differences in recall of real or nonsense words.Psychol Rep2003;93:263—4.

109.Neri AL,Ongaratto LL,Yassuda MS.M ini-mental state exam ination sentence w riting among community-dwelling elderly adults in Brazil: text fl uency and grammar complexity.IntPsychogeriatr2012;24:1732—7.

110.Munro CA,Winicki JM,Schretlen DJ,Gower EW,Turano KA, Mun˜oz B,et al.Sex differences in cognition in healthy elderly individuals.Neuropsychol Dev Cogn BAging Neuropsychol Cogn2012;19:759—68.

111.Murre JM,Janssen SM,Rouw R,Meete M.The rise and fall of immediate and delayed memory for verbal and visuospatial information from late childhood to late adulthood.ActaPsychol(Amst)2013;142:96—107.

112.Heinzel S,Metzger FG,Ehlis AC,Korell R,A lboji A,Haeussinger FB, et al.Aging-related cortical reorganization of verbal fluency processing: a functional near-infrared spectroscopy study.Neurobiol Aging2013;34:439—50.

Received 14 February 2014;revised 5 March 2014;accepted 11 March 2014

E-mail address:rli@rfdn.org

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport

2095-2546/$-see front matter CopyrightⒸ2014,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.A ll rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2014.03.012

CopyrightⒸ2014,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2014年3期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2014年3期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Women’s health in exercise and aging:What do we know?

- Sex differences in exercise and drug addiction:A m ini review of animal studies

- Women and exercise in aging

- Effects of carbohydrate supplements on exercise-induced menstrual dysfunction and ovarian subcellular structural changes in rats

- Exercise training and antioxidant supplementation independently improve cognitive function in adult male and female GFAP-APOE m ice

- Surgical menopause enhances hippocampal amyloidogenesis follow ing global cerebral ischem ia