脑血管磁共振管壁成像:从不同的视角探索新的临床路径

赵锡海

脑血管易损斑块破裂随即引发的血栓栓塞,是缺血性卒中的主要病理学基础。因此,早期识别脑血管易损斑块是缺血性卒中防控的关键。引起脑血管事件的责任病灶既可以发生于颅内动脉,也可位于颅外颈动脉。有证据表明,不同种族之间易损斑块在不同血管床的发生率存在一定的差异,亚洲人群颅内动脉易损斑块可能是缺血性卒中的主要病因,而美国白种人的缺血性卒中更多是由于颅外动脉易损斑块所致(表1)[1-14]。由此可见,颅内动脉可能是国人筛查易损斑块的主要血管床。

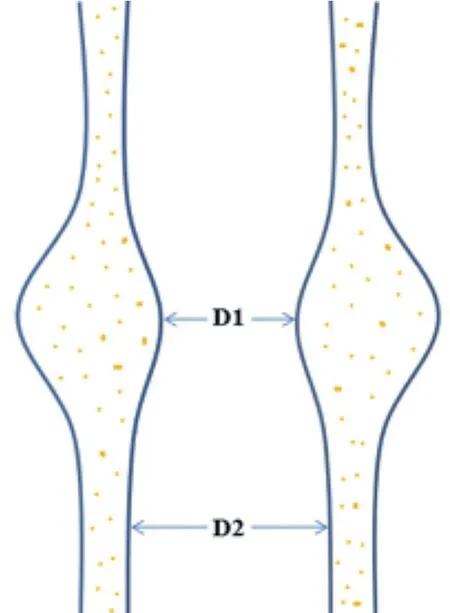

现阶段,通过各种血管成像手段[如超声、计算机断层扫描血管成像(computed tomography angiography,CTA)和磁共振血管成像(magnetic resonance angiography,MRA)]等测量管腔狭窄程度,仍然是评价脑动脉粥样硬化病变严重性的主要指标。然而,仅通过管腔信息判断斑块的易损性存在明显的低估现象。研究显示,超过20%的症状性轻度狭窄的颈动脉(狭窄<50%)存在易损斑块[15-16],甚至某些易损斑块并不引起管腔变化(狭窄=0%)[17]。这是因为粥样硬化病变在发生、发展过程中存在“正性重构效应”,即病变向血管壁外膨胀性生长,而不引起管腔严重狭窄(图1)[18]。这种正性重构效应广泛存在于全身各个血管床,包括颅内动脉和颅外颈动脉。因此,单纯测量管腔狭窄并不能客观反映粥样硬化病变的严重性。

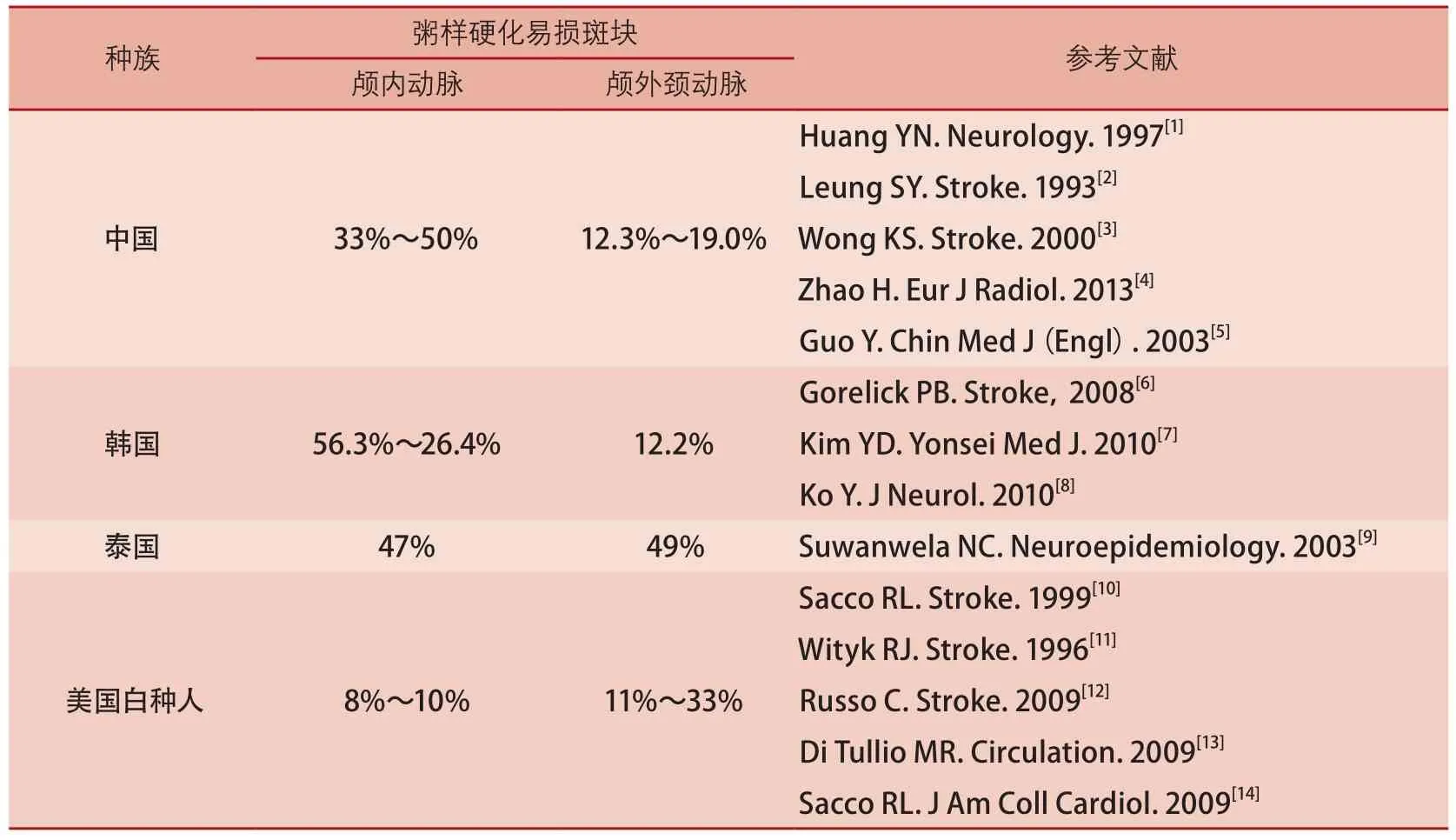

表1 脑血管病患者颅内外动脉易损斑块发生率的人群差异

注:粥样硬化斑块向血管外膨胀性生长,仅造成管腔轻度狭窄,狭窄程度:(D2-D1)/D2×100%=35%

病理学上,粥样硬化易损斑块主要表现为动脉管壁形态与成分的变化。易损斑块通常表现为较大的斑块负荷(厚度、面积或体积)、大脂质核薄纤维帽、斑块内出血、纤维帽破裂或炎症反应及新生血管[19]。管腔狭窄只是粥样硬化病变进展产生的间接征象。基于以上事实,评价易损斑块的技术关键是如何敏感识别动脉管壁的成分特征,而不是单纯测量管腔狭窄程度。

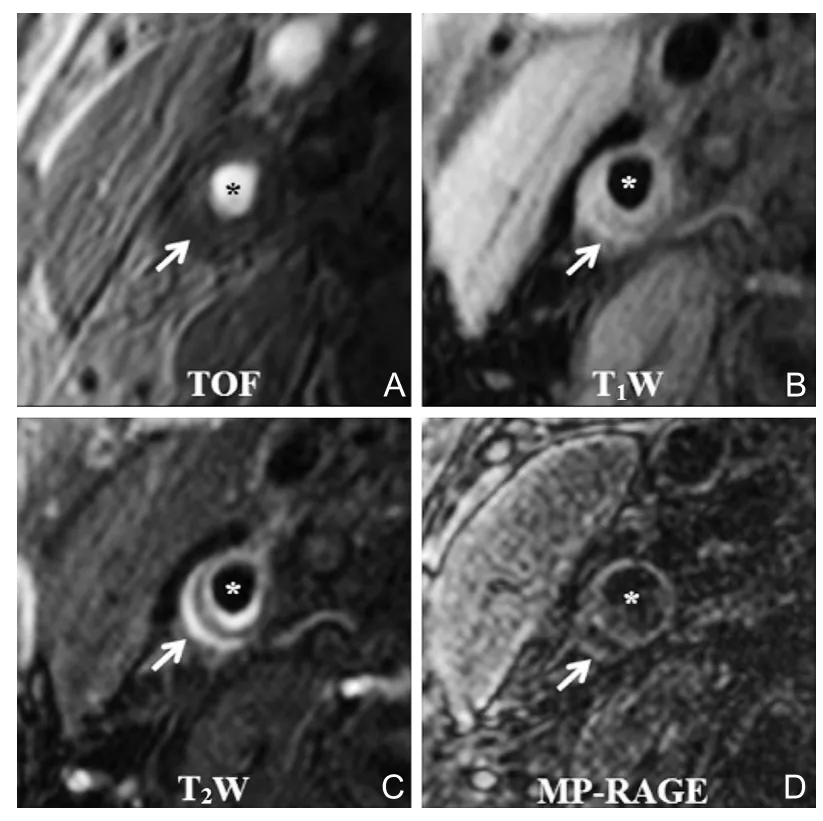

磁共振高分辨率管壁成像技术,是目前评价颈动脉易损斑块最为可靠的无创性影像学手段。这一技术的核心是应用特殊的磁共振血流抑制技术(即黑血技术)抑制管腔流动的血液信号,同时结合脂肪抑制技术,获得动脉管壁与管腔血流和管壁周围脂肪间隙之间鲜明的信号对比,从而实现对动脉管壁的直接成像。此外,该技术还采用多对比度成像方法来识别斑块成分[20-22],即时间飞跃法血管成像(timeof-flight,TOF)、T1加权像(T1weighted imaging,T1WI)、T2加权像(T2weighted imaging,T2WI)和磁化准备快速回波序列(magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo sequences,MP-RAGE),利用不同物质在不同对比度图像上表现特征的差异性,来准确识别斑块内各种成分,从而评价斑块的易损性(图2)。与病理学对照研究证实,磁共振高分辨率管壁成像技术几乎能准确识别所有易损斑块的特征[21-22]。

图2 颈动脉磁共振多对比度管壁成像

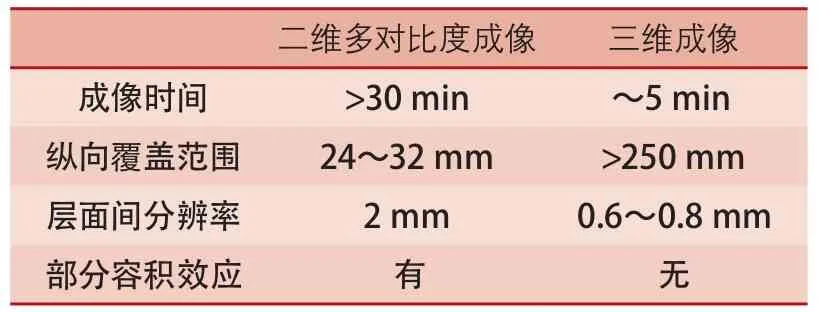

近年来,随着磁共振成像技术的快速发展,管壁成像亦由原来的二维成像发展为三维成像。如表2所示,传统的二维多对比度管壁成像存在耗时长、覆盖范围小、层面间分辨率低、迂曲血管存在部分容积效应等缺点。近来,有学者研究开发出三维管壁成像序列用于评价脑血管易损斑块,如运动敏感驱动快速梯度回波(motion-sensitizing driven equilibrium rapid gradient echo sequence,MERGE)[23]、非增强血管成像与斑块内出血同时成像序列(simultaneous noncontrast angiography and intraplaque hemorrhage,SNAP)[24]和等体素快速自旋回波采集序列(volume isotropic TSE acquisition,VISTA)/快速自旋回波(sampling perfection with application-optimized contrasts by using different flip angle evolutions,SPACE)[25]。三维成像序列具有扫描速度快、覆盖范围大等优点,大大提高了成像效率,并且使颅内外脑血管壁一站式成像成为可能。应用三维管壁成像技术,能够直观显示脑动脉粥样硬化病变的大小、形态以及位置分布,尤其对多发病变的显示更具优势(图3)。

通过磁共振管壁成像,可以获得丰富的脑动脉粥样硬化病变的量化信息,为临床诊断、治疗方案的选择、疗效评价及预防提供重要依据。管壁厚度、管壁面积、管壁体积及标准化管壁指数[管壁面积/(管壁面积+管腔面积)×100%]等是斑块负荷的常用测量指标,这些反映粥样硬化病变大小的参数与斑块的易损性具有一定的相关性。通过管壁成像定性和定量评价斑块成分特征(如钙化、脂质核、斑块内出血、纤维帽破裂等),对于斑块易损性的判断、脑血管事件风险的预测、决策临床治疗方案以及他汀类药物治疗效果的评价具有重要意义。纤维帽破裂、斑块内出血和较大的

表2 二维和三维管壁成像的对比

图3 三维管壁成像技术(MERGE)对脑血管粥样硬化病变的显示

脂质核(脂质核占据>40%的管壁面积)并伴有薄纤维帽是典型的易损斑块特征。此外,通过磁共振动态增强技术测得的管壁高传输常数(transfer constant,Ktrans)或血浆容积分数(fractional plasma volume,Vp)反映的是局部炎症反应和新生血管化的程度,存在这一特征的斑块同样具有一定的破裂风险[26]。一系列前瞻性研究证实,纤维帽破裂、斑块内出血和

脂质核大小是脑血管事件的有效预测指标(表3)[27-32]。管壁成像获得的斑块特征信息还可以用于决策临床治疗方案。Yamada等[33]研究发现,颈动脉出血性斑块进行支架植入术围术期发生静默脑梗死的概率是61%,这一比例明显高于内膜剥脱术(13%)。由于磁共振管壁成像是一项具有高度可重复性的技术,现已被广泛应用于监测他汀类药物治疗粥样硬化病变疗效的方面[34-35]。

磁共振管壁成像能够精准识别脑动脉粥样硬化易损斑块,并可对其进行全面的定性和定量分析,充分利用管壁成像获得的斑块信息可能会改变脑血管病的临床路径。首先,对于脑动脉粥样硬化病变严重性的评价,不应仅局限于测量管腔狭窄程度,需要重点关注病变局部管壁的成分特征;其次,在临床决策再血管化治疗方案环节,充分考虑斑块的成分特征(如有无斑块内出血)有可能会降低围术期并发症,从而增加患者获益;再次,对他汀类药物治疗效果评价传统的做法局限于监测血脂水平的变化,而不是直接观察靶血管粥样硬化病变有无进展或退缩。由于磁共振管壁成像能够直接显示和准确定量斑块内脂质核成分,为临床观察药物疗效提供了有效的监测手段;最后,磁共振管壁成像能够对脑动脉粥样硬化病变的破裂风险进行分层分析,这将为制订脑血管病的预防策略提供重要依据。当然,磁共振管壁成像获得的信息能否改变临床路径,还需要开展大规模前瞻性研究以提供更多的循证医学证据。

表3 磁共振斑块特征预测脑血管事件

1 Huang YN, Gao S, Li SW, et al. Vascular lesions in Chinese patients with transient ischemic attacks[J].Neurology, 1997, 48:524-525.

2 Leung SY, Ng TH, Yuen ST, et al. Pattern of cerebral atherosclerosis in Hong Kong Chinese. Severity in intracranial and extracranial vessels[J]. Stroke, 1993,24:779-786.

3 Wong KS, Li H, Chan YL, et al. Use of transcranial Doppler ultrasound to predict outcome in patients with intracranial large-artery occlusive disease[J]. Stroke,2000, 31:2641-2647.

4 Zhao H, Zhao X, Liu X, et al. Association of carotid atherosclerotic plaque features with acute ischemic stroke:a magnetic resonance imaging study[J]. Eur J Radiol, 2013, 82:e465-e470.

5 Guo Y, Jiang X, Chen S, et al. Aortic arch and intra-/extracranial cerebral arterial atherosclerosis in patients suffering acute ischemic strokes[J]. Chin Med J (Engl),2003, 116:1840-1844.

6 Gorelick PB, Wong KS, Bae HJ, et al. Large artery intracranial occlusive disease:a large worldwide burden but a relatively neglected frontier[J]. Stroke, 2008,39:2396-2399.

7 Kim YD, Choi HY, Cho HJ, et al. Increasing frequency and burden of cerebral artery atherosclerosis in Korean stroke patients[J]. Yonsei Med J, 2010, 51:318-325.

8 Ko Y, Park JH, Yang MH, et al. Signif i cance of aortic atherosclerotic disease in possibly embolic stroke:64-multidetector row computed tomography study[J]. J Neurol, 2010, 257:699-705.

9 Suwanwela NC, Chutinetr A. Risk factors for atherosclerosis of cervicocerebral arteries:intracranial versus extracranial[J]. Neuroepidemiology, 2003, 22:37-40.

10 Sacco RL, Kargman DE, Gu Q, et al. Race-ethnicity and determinants of intracranial atherosclerotic cerebral infarction. The Northern Manhattan Stroke Study[J]. Stroke, 1999, 26:14-20.

11 Wityk RJ, Lehman D, Klag M, et al. Race and sex differences in the distribution of cerebral atherosclerosis[J]. Stroke, 1996, 27:1974-1980.

12 Russo C, Jin Z, Rundek T, et al. Atherosclerotic disease of the proximal aorta and the risk of vascular events in a population-based cohort:the Aortic Plaques and Risk of Ischemic Stroke (APRIS) study[J]. Stroke, 2009,40:2313-2318.

13 Di Tullio MR, Russo C, Jin Z, et al. Aortic arch plaques and risk of recurrent stroke and death[J]. Circulation,2009, 119:2376-2382.

14 Sacco RL, Khatri M, Rundek T, et al. Improving global vascular risk prediction with behavioral and anthropometric factors. The multiethnic NOMAS(Northern Manhattan Cohort Study)[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2009, 54:2303-2311.

15 Saam T, Underhill HR, Chu B, et al. Prevalence of American Heart Association type VI carotid atherosclerotic lesions identif i ed by magnetic resonance imaging for different levels of stenosis as measured by duplex ultrasound[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2008, 51:1014-1021.

16 Zhao X, Underhill HR, Zhao Q, et al. Discriminating carotid atherosclerotic lesion severity by luminal stenosis and plaque burden:a comparison utilizing high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging at 3.0 Tesla[J]. Stroke, 2011, 42:347-353.

17 Dong L, Underhill HR, Yu W, et al. Geometric and compositional appearance of atheroma in an angiographically normal carotid artery in patients with atherosclerosis[J]. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2010,31:311-316.

18 Glagov S, Weisenberg E, Zarins CK, et al.Compensatory enlargement of human atherosclerotic coronary arteries[J]. N Engl J Med, 1987, 316:1371-1375.

19 Naghavi M, Libby P, Falk E, et al. From vulnerable plaque to vulnerable patient:a call for new def i nitions and risk assessment strategies:Part I[J]. Circulation,2003, 108:1664-1672.

20 Yuan C, Mitsumori LM, Ferguson MS, et al. In vivo accuracy of multispectral magnetic resonance imaging for identifying lipid-rich necrotic cores and intraplaque hemorrhage in advanced human carotid plaques[J].Circulation, 2001, 104:2051-2056.

21 Cai JM, Hatsukami TS, Ferguson MS, et al.Classification of human carotid atherosclerotic lesions with in vivo multicontrast magnetic resonance imaging[J]. Circulation, 2002, 106:1368-1373.

22 Saam T, Ferguson MS, Yarnykh VL, et al. Quantitative evaluation of carotid plaque composition by in vivo MRI[J]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2005, 25:234-239.

23 Balu N, Yarnykh VL, Chu B, et al. Carotid plaque assessment using fast 3D isotropic resolution blackblood MRI[J]. Magn Reson Med, 2011, 65:627-637.

24 Wang J, Börnert P, Zhao H, et al. Simultaneous noncontrast angiography and intraplaque hemorrhage(SNAP) imaging for carotid atherosclerotic disease evaluation[J]. Magn Reson Med, 2013, 69:337-345.

25 Fan Z, Zhang Z, Chung YC, et al. Carotid arterial wall MRI at 3T using 3D variable-f l ip-angle turbo spin-echo(TSE) with fl ow-sensitive dephasing (FSD)[J]. J Magn Reson Imaging, 2010, 31:645-654.

26 Kerwin WS, O'Brien KD, Ferguson MS, et al.Inflammation in carotid atherosclerotic plaque:a dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging study[J].Radiology, 2006, 241:459-468.

27 Takaya N, Yuan C, Chu B, et al. Association between carotid plaque characteristics and subsequent ischemic cerebrovascular events:a prospective assessment with MRI--initial results[J]. Stroke, 2006, 37:818-823.

28 Sadat U, Teng Z, Young VE, et al. Association between biomechanical structural stresses of atherosclerotic carotid plaques and subsequent ischaemic cerebrovascular events--a longitudinal in vivo magnetic resonance imaging-based fi nite element study[J]. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg, 2010, 40:485-491.

29 Kwee RM, van Oostenbrugge RJ, Mess WH, et al. MRI of carotid atherosclerosis to identify TIA and stroke patients who are at risk of a recurrence[J]. J Magn Reson Imaging, 2013, 37:1189-1194.

30 Singh N, Moody AR, Gladstone DJ, et al. Moderate carotid artery stenosis:MR imaging-depicted intraplaque hemorrhage predicts risk of cerebrovascular ischemic events in asymptomatic men[J]. Radiology,2009, 252:502-508.

31 Hosseini AA, Kandiyil N, Macsweeney ST, et al.Carotid plaque hemorrhage on magnetic resonance imaging strongly predicts recurrent ischemia and stroke[J]. Ann Neurol, 2013, 73:774-784.

32 Mono ML, Karameshev A, Slotboom J, et al. Plaque characteristics of asymptomatic carotid stenosis and risk of stroke[J]. Cerebrovasc Dis, 2012, 34:343-350.

33 Yamada K, Yoshimura S, Kawasaki M, et al. Embolic complications after carotid artery stenting or carotid endarterectomy are associated with tissue characteristics of carotid plaques evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging[J]. Atherosclerosis, 2011, 215:399-404.

34 Underhill HR, Yuan C, Zhao XQ, et al. Effect of rosuvastatin therapy on carotid plaque morphology and composition in moderately hypercholesterolemic patients:a high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging trial[J]. Am Heart J, 2008, 155:584.e1-8.

35 Zhao XQ, Dong L, Hatsukami T, et al. MR imaging of carotid plaque composition during lipid-lowering therapy:a prospective assessment of effect and time course[J]. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging, 2011, 4:977-986.