中缅树鼩精子形态特征及冷冻损伤

张远旭, 平述煌, 杨世华,*

(1. 昆明理工大学 生命科学与技术学院衰老与肿瘤分子遗传学实验室, 云南 昆明650500; 2. 中国科学院和云南省动物模型与人类疾病机理重点实验室, 中国科学院昆明动物研究所, 云南 昆明 650223)

中缅树鼩精子形态特征及冷冻损伤

张远旭1,2, 平述煌1, 杨世华1,*

(1.昆明理工大学 生命科学与技术学院衰老与肿瘤分子遗传学实验室,云南 昆明650500; 2.中国科学院和云南省动物模型与人类疾病机理重点实验室,中国科学院昆明动物研究所,云南 昆明650223)

树鼩作为一种新型的、接近灵长类的实验动物, 在医学生物学上的应用受到越来越多的重视。精子的结构特性研究及冷冻后结构的完整性分析是精子生物学的主要内容, 也有助于树鼩的实验室快速繁殖。该研究采用人工饲养的中缅树鼩(Tupaia belangeri chinensis), 结果显示其睾丸占总体重的(1.05±0.07)%, 总体积为(1.12±0.10) mL。附睾尾及输精管精子总量估计在2.2×107~8.8×107, 其运动度和顶体完整率分别为(68.8±3.9)%和(90.0±2.1)%。利用扫描电子显微镜和透射电子显微镜对树鼩附睾精子的超微结构进行的观察和分析显示精子头部呈圆形或卵圆形; 头部长度、宽度平均分别为6.65和5.82 μm; 精子尾部中段、主段、尾段和精子总长度平均分别为13.39、52.35、65.74和73.05 μm; 尾部中段的线粒体螺旋数量为48个, 其轴丝结构为典型的“9+9+2”结构。冷冻解冻后的精子主要表现在顶体与质膜不完整、精子断裂、尾部扭曲和膨大。上述结果提示树鼩精子与其他哺乳动物精子的结构特征相似, 但是精子大小和线粒体螺旋数目有明显的差别, 且超微结构改变仍是冷冻精子运动和受精能力下降的主要原因。

树鼩; 睾丸; 精子; 形态结构; 冷冻损伤

树鼩是一种昼行、树栖的小型哺乳动物, 曾被定义为攀鼩目、灵长目(Liu et al, 2001; Wong & Kaas, 2009), 目前对树鼩的分类地位仍然存在争议。但无论如何, 树鼩是最接近于灵长类的小型哺乳动物,具有许多灵长类动物共有的特征(Poonkhum et al, 2000)。树鼩在人类医学及生物学研究方面具有重要地位, 如神经生物学(Remple et al, 2007)、人类肝炎病毒感染(Xu et al, 2007; Li et al, 2008)、视觉系统发育(Poveda & Kretz, 2009)及群体阶层应激(Kozicz et al, 2008; Zambello et al, 2010)等。目前, 有关雄性树鼩生殖生物学研究的报道较少(Collins et al, 2007)。Collins et al于1982年报道了雄性树鼩生殖道的解剖学特征和生理功能(Collins et al, 1982); 随后, 有研究报道了雄性树鼩从出生到性成熟过程的生殖器官生长与发育(Collins & Tsang, 1987); 精子细胞在睾丸内的成熟过程(Maeda et al, 1998); 雄性树鼩精子的形成和染色质凝聚(Suphamungmee et al, 2008)等结果。然而, 树鼩睾丸、精子形态结构特性的研究仍然很有限。我们曾报道树鼩精子可以被冷冻保存(Ping et al, 2011), 但是精子冷冻后的超微结构变化尚不清楚。为此, 本研究分析树鼩的睾丸、附睾精子的形态学结构特征, 以及树鼩精子冷冻复苏后的结构变化。

1 材料和方法

1.1 实验材料

4只健康的成年雄性树鼩, 均来自中科院昆明动物研究所。所有实验均在当年3—5月份完成。除特殊说明外, 所用化学试剂均购自Sigma公司(St. Louis, MO, USA)。精子稀释液为TALP-HEPES (modified Tyrode’s solution with albumin, lactate and pyruvate) (Bavister et al, 1983), 冷冻液为TTE(Tris-TES-egg yolk)(Si et al, 2000), 均按照文献中描述的方法配制。

1.2 实验方法

1.2.1 睾丸的称重和测量 氯胺酮(60~70 mg/kg体重)经肌肉注射, 待树鼩麻醉后称其体重。在麻醉状态下, 外科手术暴露腹腔后取出睾丸、附睾及输精管; 在附睾头、尾相连处中间部分分离彼此, 并对上述各部分分别称重; 游标卡尺测定睾丸的纵横长度; 将分离得到的睾丸分别缓慢浸入含有3 mL生理盐水的5 mL量筒中, 通过观察量筒中液体体积的增加来确定睾丸的体积。

1.2.2 精子收集与分析 分离获得的附睾尾和输精管置于平皿中, 37 ℃TALP-HEPES洗涤; 随后置于1 mL TALP-HEPES中剪至~1 cm, 用镊子轻轻挤压管腔以释放储存的精子; 微量移液器吸取所有精液, 混匀后取10 μL精液样品检测精子的数量、运动度和顶体完整性; 剩余的精子经离心处理后将沉淀精子固定, 用于超微结构分析。

精子计数和运动度测定 10 μL新鲜精子用TALP-HEPES稀释100~500倍后取10 μL滴加到已预热至37 ℃的血细胞计数板上, 在光学显微镜下计数前向运动精子和原地不动精子, 用二者数量之和计算每只树鼩获得精子数量; 运动精子占所有计数精子的百分比即为精子运动度, 其操作步骤参考文献报道(Saragusty et al, 2009)。每次至少计数200个精子, 重复两次。

顶体完整率检测 荧光染料FITC-PNA检测精子的顶体完整率, 其操作步骤见文献报道(Ping et al, 2011)。简要描述如下:精子样品在TALP-HEPES中2 500 r/min、5 min离心和洗涤2次, 并稀释至~1×105个/mL; 取20 μL滴在载玻片上, 自然风干后,在通风橱中用甲醇溶液浸泡固定5 min; 载玻片取出风干后, 加入40 μg/mL FITC-PNA 40 μL于精子样品上并在37 ℃培养箱中避光孵育30 min; PBS(pH 7.2)洗去多余的染料, 在荧光显微镜下检查,其激发光波长和发射光波长分别为490和515 nm。顶体完整的精子均匀地着上苹果绿色, 而顶体不完整的精子部分着色或不着色。计数顶体完整和不完整的精子, 每次至少计数200个, 顶体完整精子占所有计数精子的比率为精子顶体完整率。

1.2.3 精子冷冻程序 冷冻方法参照Ping et al (2011)。从雄性树鼩附睾中获取精子, 离心洗涤后TTE稀释至浓度为4×106个/mL; 将其置于4 ℃冰箱中进行预冷处理, 直至精子混合液降到4 ℃; 将精子混合液装入0.25 mL冷冻麦管, 水平放置在15 cm×10 cm的铝架上并将铝架悬挂在离液氮面4 cm的位置上平衡10 min; 随后将冷冻麦管投入液氮中冷冻保存。冷冻保存2 d后, 取出麦管, 直接投入37 ℃水浴中解冻; 解冻后将精子释放到1.5 mL离心管中, 并用5×精液体积的TALP-HEPES稀释;随后以2 500 r/min、5 min离心洗涤1次, 将沉淀精子按电镜样品的制作方法处理。

1.2.4 电镜样品的处理与观察 扫描电镜样品的处理方法参照文献(Simeo et al, 2010)报道进行。简述如下:冷冻−复苏精子的沉淀中加入2.5%戊二醛PBS缓冲液(0.1 mol/L, pH 7.4, 4 ℃), 4 ℃前固定24 h; PBS缓冲液轻轻漂洗6次, 其中前3次每次10 min,后3次每次20 min; 质量分数为1%~2%的锇酸4 ℃后固定1 h; 双固定后, PBS缓冲液漂洗3次, 其中前2次每次5 min, 后1次30 min; 系列酒精逐级脱水; 冷冻干燥处理, 以及离子溅射仪喷金; 扫描电子显微镜观察精子外部形态结构并拍照和分析。

透射电镜样品的处理 样品处理也参照文献(Simeo et al,2010)报道进行。简述如下:冷冻−复苏精子的沉淀中加入2.5%戊二醛PBS缓冲液(0.1 mol/L, pH 7.4), 4 ℃前固定24 h; PBS缓冲液漂洗6次, 其中前3次每次10 min, 后3次每次20 min; 质量分数为1%的锇酸4 ℃后固定1 h; 双固定后, PBS缓冲液漂洗3次, 其中前2次每次5 min, 后1次30 min; 梯度酒精、丙酮逐级脱水; Epon618环氧树脂渗透、包埋、半切片、光镜定位、修块; Lecia-R超薄切片机切片(切片厚约90 nm); 切片经柠檬酸铅和醋酸双氧铀双重染色后用透射电子显微镜观察精子超微结构并拍照和分析。

2 结 果

2.1 树鼩睾丸和附睾精子的形态与特征

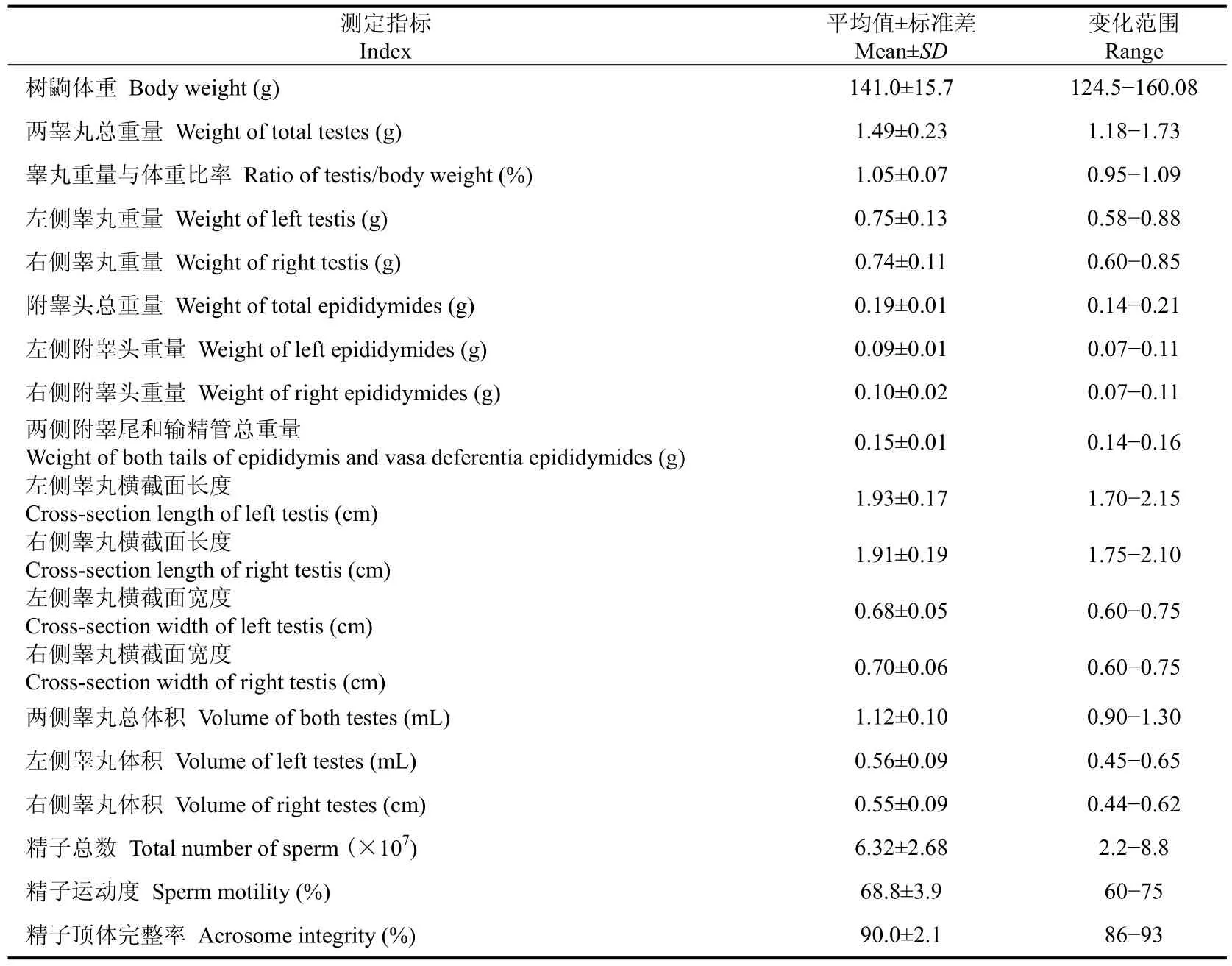

测定结果见表1。

表1 树鼩睾丸大小及附睾精子特征Tab. 1 Testis measurements and sperm characteristics of tree shrew

2.2 树鼩精子的超微结构

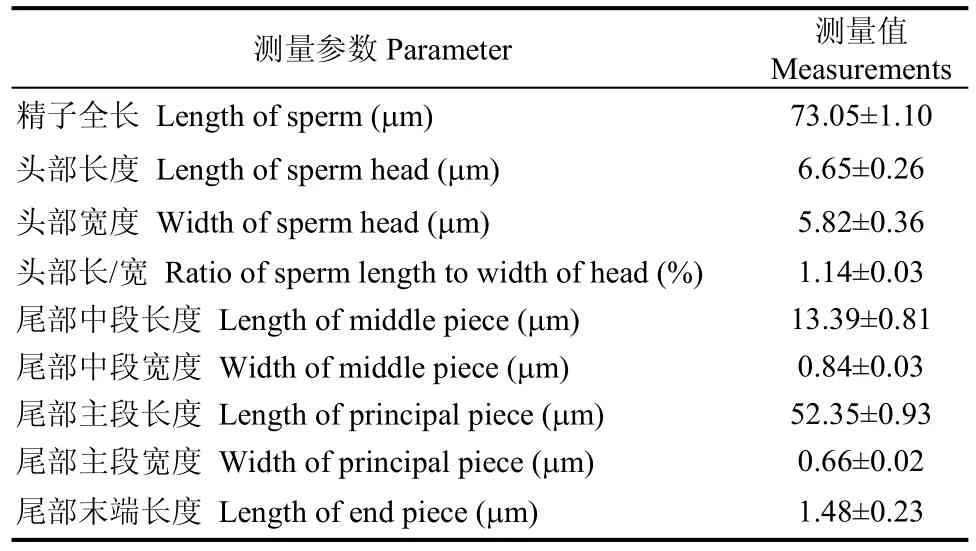

新鲜树鼩精子超微结构见表2。

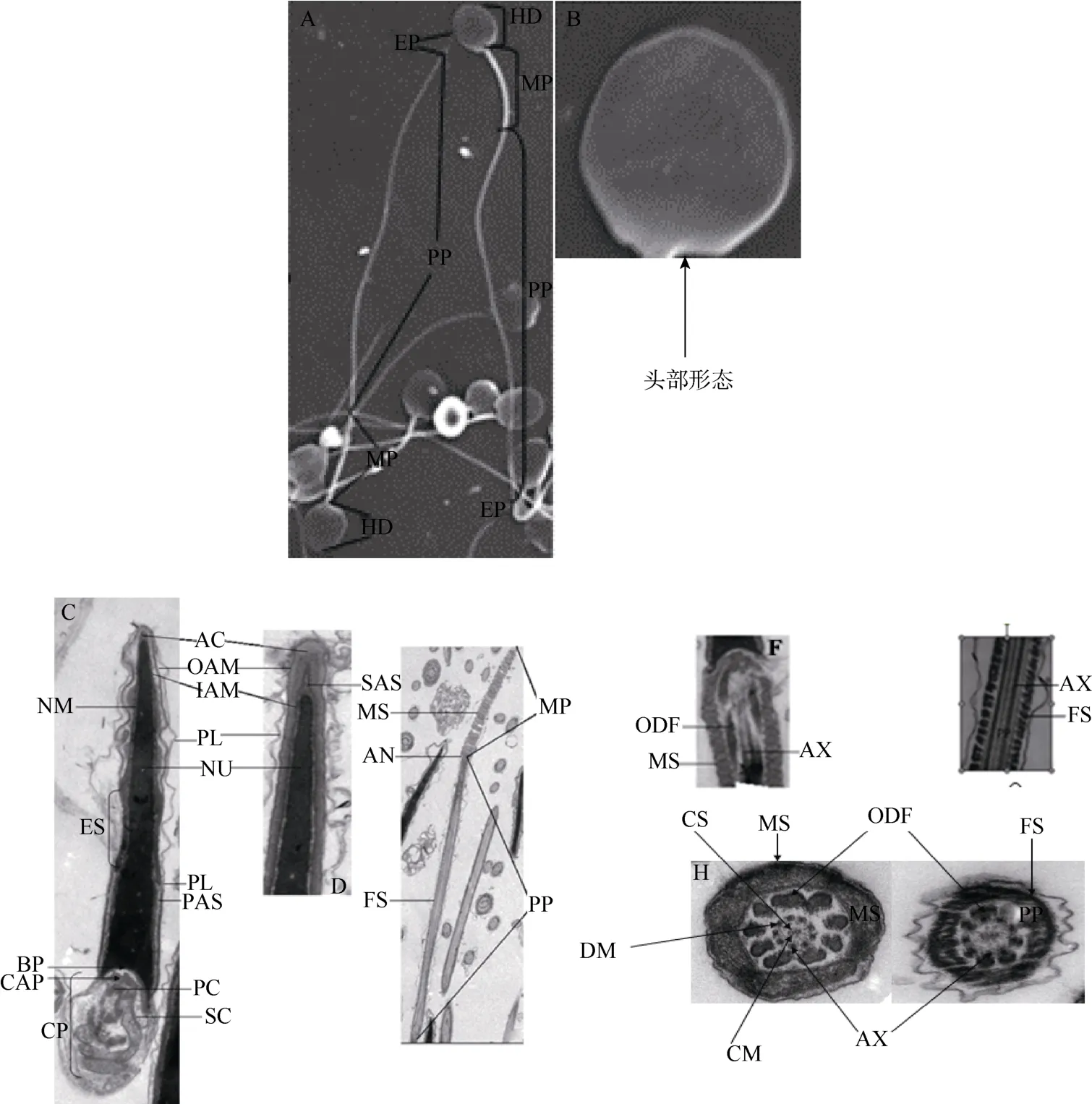

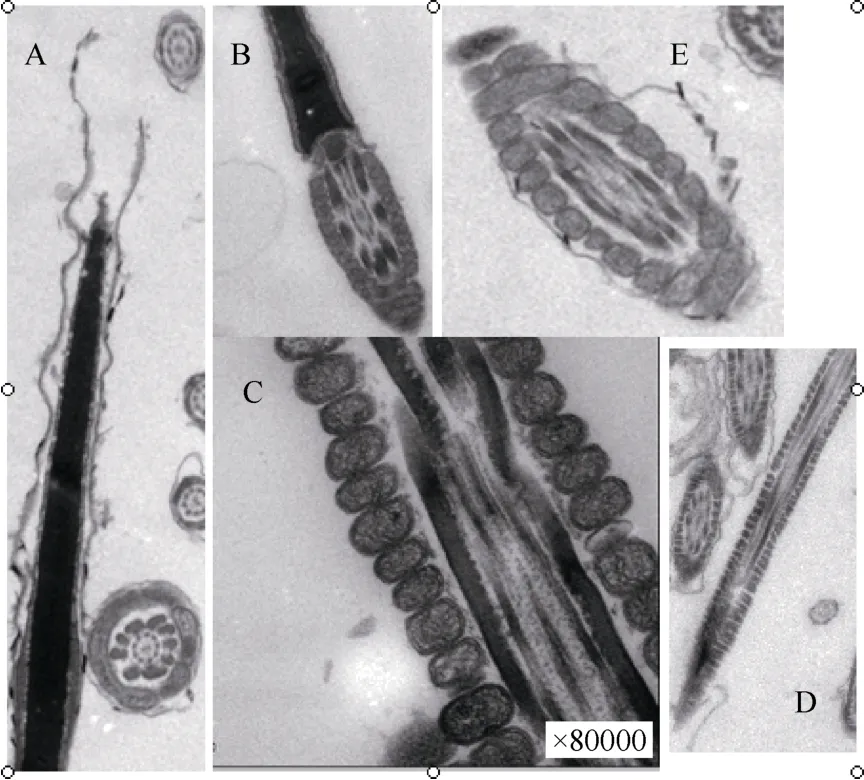

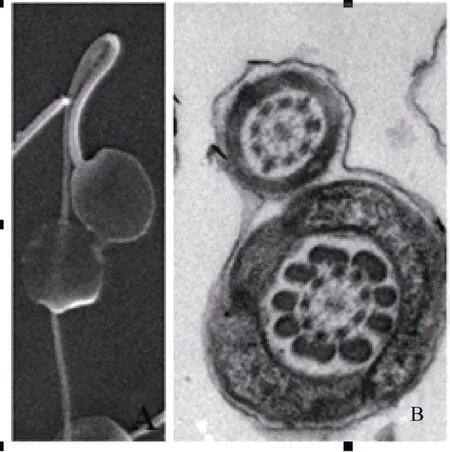

树鼩精子由头、尾部组成, 尾部是精子最长的部分, 可分为中段、主段和末段等三部分(表2和图1A, B)。在扫描电镜下, 精子头部呈圆形或卵圆形;精子尾部明显分为中段(mid-piece, MP)、主段(principal piece, PP)和末段(end piece)。在透射电镜下, 整个精子由质膜包裹, 其中头部顶体区域的质膜连接呈松弛状态; 头部由核、顶体和后顶体鞘组成; 顶体为一位于头顶部的薄层帽状囊腔; 顶体和核之间存在顶体下间隙(subacrosomal space, SAS);核由核膜包被, 为头部的主要组成部分, 占据头部的绝大部分体积, 其电子密度大而均匀; 核膜外为电子密度小而均匀的顶体; 由头后端向前端, 核膜逐渐变薄, 在赤道段区域最坚固(图1C, D)。

头部核末端有一个凹面植入窝, 与颈部的小头嵌合; 颈部, 又称连接段, 由小头、节柱和近端中心粒组成; 小头的凸型致密纤维板结构, 与核末端的植入窝基板线相吻合; 稀疏、适度的电子致密物质填充在基板线和小头的间隙里(图1C)。

表2 树鼩精子细胞的形态测定参数Tab. 2 Morphometry of epididymal sperm of tree shrew

图1 树鼩精子的超微结构Fig. 1 Tree shrew sperm morphology

尾主要由轴丝和外周致密纤维组成; 轴丝起于精子颈部, 延伸至尾部末段; 轴丝由9对双联体周围微管和一对中央微管组成, 9对双联体周围微管均匀环绕在中央微管周围, 形成了“9+9+2”的微管构造; 每一对双联体均由一个小的圆柱状微管和一个不完整C形微管组成; 从中心微管到周围微管呈现放射状延伸, 一对中心微管由一个短桥连接。在尾部中段和主段, 轴丝均有9根外周致密纤维环绕,每一根外周致密纤维伴随一对双联体微管; 纤维横截面呈现花瓣状、黄豆状或圆形。以中心微管轴丝为基准将外周致密纤维按顺时针方向编号1~9, 结果发现外周致密纤维大小不同:尾部中段, 1、2、5、6外周致密纤维明显较其他纤维粗; 尾部主段, 1、5、6外周致密纤维也明显较其他纤维粗; 尾部中段靠近颈部的纤维较粗, 主段靠近尾部末段的纤维较细(图1E−H)。

外周致密纤维在尾部中段由线粒体鞘环绕, 在主段由纤维鞘环绕。在尾部中段, 线粒体头尾相接形成一个螺旋环绕致密纤维; 精子线粒体螺旋数为48; 在线粒体鞘的末端有一个三角状环, 连接质膜基底和向内突出的致密纤维顶端; 环位于螺旋状线粒体末端和主段纤维鞘前端之间, 为中段和主段的分界线。纤维鞘从精子主段延伸到末段, 其电子密度高, 且越靠近末端越细, 直至消失; 纤维鞘由背、腹侧纵柱及其环形连接肋柱组成, 且这两个纵柱似乎固定在外周致密纤维3和8上(图1E−G)。

2.3 冷冻复苏精子形态结构的变化

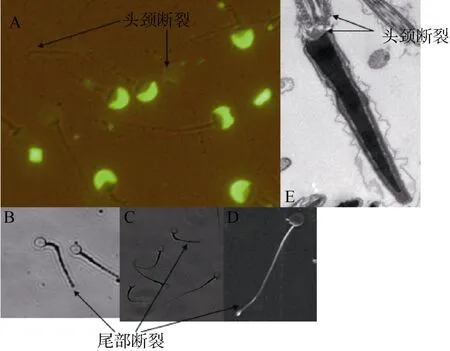

鲜精精子运动度和顶体完整率分别为(68.82±3.95)%和(89.99±2.14)%, 解冻后精子复苏运动度和顶体完整率分别为(44.73±3.67)%和(76.52±1.84)%。 FITC-PNA荧光染色后, 可见经冷冻/解冻, 部分精子的顶体表现出部分或完全缺失(图2A); 精子头部核表面的顶体不匀称, 表明经冷冻/解冻后, 精子顶体结构出现损伤(图2 B,C); 精子头部核表面无可见顶体, 表明顶体完全缺失(图2D)。

图2 冷冻/解冻精子头部顶体的缺损Fig. 2 Sperm acrosome defects after freezing and thawing

经过冷冻/解冻处理后, 精子膜结构变化主要表现在以下几个方面(图2):头部顶体处质膜破损;头部和颈部连接处质膜缺失; 尾部中段线粒体鞘外质膜缺失; 尾部主段质膜缺失; 线粒体膜不完整。

在冷冻/解冻过程中, 外来冷冻压力会造成精子的机械性损伤, 导致其不完整结构。头、颈部断裂致头、尾部分离(图4A, E); 尾部中段、主段断裂;尾部主段、末段断裂(图4B−D)。

图3 冷冻/解冻精子质膜的缺损Fig. 3 Sperm plasma membrane defects after freezing and thawing

图4 冷冻/解冻精子不同部位间的断裂Fig. 4 Sperm breakage in different locus after freezing and thawing

冷冻/解冻对精子的另一个损伤体现于尾部的弯曲度。精子尾部弯曲通常发生于中段或主段(图5), 致使主段和中段的线粒体被同一质膜包裹, 造成轴丝结构受损, 进而导致精子运动功能丧失。

图5 冷冻/解冻精子尾部的弯曲Fig. 5 Coiled sperm tail after freezing and thawing

解冻过程中, 渗透性防冻剂致使胞内渗透压高于胞外, 胞外水向胞内流入, 有可能进而导致细胞膨胀, 如精子尾部中段膨胀(图6)。

4 讨 论

与哺乳动物及灵长类精子相似, 树鼩精子头部呈卵圆形(Downing et al, 2005)。不同物种精子头部的长度和宽度各不相同, 如人类为4.5 μm和3 μm (Pedersen, 1969), 黑熊为6.57 μm和4.76 μm (Brito et al, 2010), 而树鼩为6.65 μm和5.82 μm。树鼩精子全长为73.05 μm, 与眼镜熊和河狸精子长度相似(Gage, 1998; Bierla et al, 2007), 但与仓鼠(119 μm) (Nagy, 1994)和人类(55~60 μm)差异显著。另外,由于挤压释放附睾尾和输精管中的精子, 所计算的精子总数可能存在差异, 但损失精子比例可能很小。

图6 冷冻/解冻精子尾部中段的膨胀Fig. 6 Swollen sperm tail mid-piece after freezing and thawing

线粒体鞘在精子尾部中段呈螺旋形包绕外周致密纤维, 不同物种动物精子尾部中段的线粒体螺旋数各异:人类为15个; 仓鼠为133个(Nagy, 1994);黑熊为59个(Gage, 1998), 而树鼩为48个。

轴丝由与精子运动密切相关的微管组成。不同物种动物精子尾部的轴丝结构不同, 树鼩精子的轴丝结构类似于人类、蟹、长鼻浣熊、野猪及蜜蜂, 即为“9+9+2”型(EI-Shoura et al, 1995; Báo et al, 2004; Fischman et al, 2009; Lima et al, 2009; Mancini et al, 2009)。

哺乳动物冷冻精子的受精率和受孕率较鲜精为低(O'Meara et al, 2005), 因为在冷冻过程中, 精子经受着许多外来压力的考验, 如冷休克、膜相转换、冰晶形成等(Aboagla & Terada, 2004; White, 1993)。冷休克会导致部分精子运动能力丧失、膜结构损伤(Jones & Martin, 1973; Ortman & Rodriguez-Martinez, 1994)及线粒体膜电位改变(Watson, 1995)。冷冻时, 由于细胞外冰晶形成将造成胞外液体渗透压升高, 促使细胞内水分外排, 导致细胞收缩, 如细胞膜不能承受如此剧烈的收缩变化, 将出现细胞损伤; 而解冻时, 胞外水的流入又可致使细胞破裂(Mazur, 1984)。在对树鼩冷冻/解冻精子超微结构的观察和分析中发现:树鼩精子冷冻/解冻后, 质膜和顶体最容易受到损伤, 其顶体会完全缺失或损伤;无论在头部还是尾部中段和主段, 质膜均有可能肿胀、变薄、破损、甚至缺失。同时, 解冻时, 胞内的渗透性防冻剂将导致胞内渗透压高于胞外, 细胞吸水, 进而使得细胞因渗透压梯度作用而表现为不均一膨胀, 如部分精子尾部中段膨胀。再者, 由于机械性压力影响,很容易导致树鼩精子头、颈部断裂, 尾部中段、主段断裂, 造成精子的致死性损伤。由此可见, 质膜和顶体完整性受损仍然是导致树鼩冷冻/解冻精子受精率低下的主要原因。

因此, 通过研究树鼩精子的超微结构及冷冻对超微结构的影响, 有助于改善现有的树鼩精子冷冻方法和提高树鼩的人工繁殖能力, 为低温生物学发展提供理论依据。

Aboagla EME, Terada T. 2004. Effects of egg yolk during the freezing step of cryopreservation on the viability of goat spermatozoa[J]. Theriogenology, 62(6): 1160-1172.

Báo SN, Gonçalves Simões D, Lino-Neto J. 2004. Sperm ultrastructure of the bees Exomalopsis (Exomalopsis) auropilosa Spinola 1853 and Paratetrapedia (Lophopedia) sp. Michener & Moure 1957 (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Apinae)[J]. J Submicrosc Cytol Pathol, 36(1): 23-28.

Bavister BD, Leibfried ML, Lieberman G. 1983. Development of preimplantation embryos of the golden hamster in a defined culture medium[J]. Biol Reprod, 28(1): 235-247.

Bierla JB, Gizejewski Z, Leigh CM, Ekwall H, Söderquist L, Rodriguez-Martinez H, Zalewski K, Breed WG. 2007. Sperm morphology of the Eurasian beaver, Castor fiber: an example of a species of rodent with highly derived and pleiomorphic sperm populations[J]. J Morphol, 268(8): 683-689.

Brito LF, Sertich PL, Stull GB, Rives W, Knobbe M. 2010. Sperm ultrastructure, morphometry, and abnormal morphology in American black bears (Ursus americanus)[J]. Theriogenology, 74(8):1403-1413.

Collins PM, Tsang WN. 1987. Growth and reproductive development in the male tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri) from birth to sexual maturity[J]. Biol Reprod, 37(2): 261-267.

Collins PM, Tsang WN, Lofts B. 1982. Anatomy and function of the reproductive tract in the captive male tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri)[J]. Biol Reprod, 26(1): 169-182.

Collins PM, Tsang WN, Urbanski HF. 2007. Endocrine correlates of reproductive development in the male tree-shrew (Tupaia belangeri) and the effects of infantile exposure to exogenous androgens[J]. GenComp Endocrinol, 154(1-3): 22-30.

Downing Meisner A, Klaus AV, O'Leary MA. 2005. Sperm head morphology in 36 species of artiodactylans, perissodactylans, and cetaceans (Mammalia)[J]. J Morphol, 263(2): 179-202.

EI-Shoura SM, Abdel Aziz M, Ali ME, EI-Said MM, Ali KZM, Kemeir MA, Raoof AMS, Allam M, Elmalik EMA. 1995. Deleterious effects of khat addiction on semen parameters and sperm ultrastructure[J]. Hum Reprod, 10(9): 2295-2300.

Fischman ML, Bolondi A, Cisale H. 2009. Ultrastructure of sperm 'tail stump' defect in wild boar[J]. Andrologia, 41(1): 35-38.

Gage MJG. 1998. Mammalian sperm morphometry[J]. Proc Biol Sci, 265(1391): 97-103.

Jones RC, Martin ICA. 1973. The effects of dilution, egg yolk and cooling to 5°C on the ultrastructure of ram spermatozoa[J]. J Reprod Fertil, 35(2): 311-320.

Kozicz T, Bordewin LAP, Czéh B, Fuchs E, Roubos EW. 2008. Chronic psychosocial stress affects corticotropin-releasing factor in the paraventricular nucleus and central extended amygdala as well as urocortin 1 in the non-preganglionic Edinger-Westphal nucleus of the tree shrew[J]. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 33(6): 741-754.

Li Y, Wan DF, Wei W, Su JJ, Cao J, Qiu XK, Ou C, Ban KC, Yang C, Yue HF. 2008. Candidate genes responsible for human hepatocellular carcinoma identified from differentially expressed genes in hepatocarcinogenesis of the tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri chinesis)[J]. Hepatol Res, 38(1): 85-95.

Lima GL, Barros FFPC, Costa LLM, Castelo TS, Fontenele-Neto JD, Silva AR. 2009. Determination of semen characteristics and sperm cell ultrastructure of captive coatis (Nasua nasua) collected byelectroejaculation[J]. Anim Reprod Sci, 115(1-4): 225-230.

Liu FGR, Miyamoto MM, Freire NP, Ong PQ, Tennant MR, Young TS, Gugel KF. 2001. Molecular and morphological supertrees for eutherian (placental) mammals[J]. Science, 291(5509): 1786-1789.

Maeda S, Nakamuta N, Nam SY, Kimura J, Endo H, Rerkamnuaychoke W, Kurohmaru M, Yamada J, Hayashi Y, Nishida T. 1998. Monoclonal antibody TSd-1 is specific to elongating and matured spermatids in testis of common tree shrew (Tupaia glis)[J]. J Vet Med Sci, 60(3): 345-349.

Mancini K, Lino-Neto J, Dolder H, Dallai R. 2009. Sperm ultrastructure of the European hornet Vespa crabro (Linnaeus, 1758) (Hymenoptera: Vespidae)[J]. Arthropod Struct Dev, 38(1): 54-59.

Mazur P. 1984. Freezing of living cells: mechanisms and implications[J]. Am J Physiol, 247(3 Pt 1): C125-C142.

Nagy F. 1994. On the ultrastructure of the spermatozoa in the Siberian hamster (Phodopus sungorus campbelli)[J]. J Submicrosc Cytol Pathol, 26(4): 533-544.

O'Meara CM, Hanrahan JP, Donovan A, Fair S, Rizos D, Wade M, Boland MP, Evans ACO, Lonergan P. 2005. Relationship between in vitro fertilisation of ewe oocytes and the fertility of ewes following cervical artificial insemination with frozen-thawed ram semen[J]. Theriogenology, 64(8): 1797-1808.

Ortman K, Rodriguez-Martinez H. 1994. Membrane damage during dilution, cooling and freezing-thawing of boar spermatozoa packaged in plastic bags[J]. J Vet Med Ser, 41(1-10): 37-47.

Pedersen H. 1969. Ultrastructure of the ejaculated human sperm[J]. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat, 94(4): 542-554.

Ping S, Wang F, Zhang Y, Wu C, Tang W, Luo Y, Yang S. 2011. Cryopreservation of epididymal sperm in tree shrews (Tupaia belangeri)[J]. Theriogenology, 76(1): 39-46.

Poonkhum R, Pongmayteegul S, Meeratana W, Pradidarcheep W, Thongpila S, Mingsakul T, Somana R. 2000. Cerebral microvascular architecture in the common tree shrew (Tupaia glis) revealed by plastic corrosion casts[J]. Microsc Res Tech, 50(5): 411-418.

Poveda A, Kretz R. 2009. c-Fos expression in the visual system of the tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri)[J]. J Chem Neuroanat, 37(4): 214-228.

Remple MS, Reed JL, Stepniewska I, Lyon DC, Kaas JH. 2007. The organization of frontoparietal cortex in the tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri): II. Connectional evidence for a frontal-posterior parietal network[J]. J Comp Neurol, 501(1): 121-149.

Saragusty J, Gacitua H, Rozenboim I, Arav A. 2009. Protective effects of iodixanol during bovine sperm cryopreservation[J]. Theriogenology, 71(9): 1425-1432.

Si W, Zheng P, Tang XH, He XC, Wang H, Bavister BD, Ji WZ. 2000. Cryopreservation of rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) spermatozoa and their functional assessment by in vitro fertilization[J]. Cryobiology, 41(3): 232-240.

Simeo CG, Kurtz K, Rotllant G, Chiva M, Ribes E. 2010. Sperm ultrastructure of the spider crab Maja brachydactyla (Decapoda: Brachyura)[J]. J Morphol, 271(4): 407-417.

Suphamungmee W, Wanichanon C, Vanichviriyakit R, Sobhon P. 2008. Spermiogenesis and chromatin condensation in the common tree shrew, Tupaia glis[J]. Cell Tissue Res, 331(3): 687-699.

Watson PF. 1995. Recent developments and concepts in the cryopreservation of spermatozoa and the assessment of their post-thawing function[J]. Reprod Fertil Dev, 7(4): 871-891.

White IG. 1993. Lipids and calcium uptake of sperm in relation to cold shock and preservation: a review[J]. Reprod Fertil Dev, 5(6): 639-658.

Wong PY, Kaas JH. 2009. Architectonic Subdivisions of Neocortex in the tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri)[J]. Anat Rec-Adv Int Anat Evol Biol, 292(7): 994-1027.

Xu XP, Chen HB, Cao XM, Ben KL. 2007. Efficient infection of tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri) with hepatitis C virus grown in cell culture or from patient plasma[J]. J Gen Virol, 88(9): 2504-2512.

Zambello E, Fuchs E, Abumaria N, Rygula R, Domenici E, Caberlotto L. 2010. Chronic psychosocial stress alters NPY system: different effects in rat and tree shrew[J]. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 34(1): 122-130.

Morphological characteristics and cryodamage of Chinese tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri chinensis) sperm

ZHANG Yuan-Xu1,2, PING Shu-Huang1, YANG Shi-Hua1,*

(1. Laboratory of Molecular Genetics of Aging and Tumor, Faculty of Life Science and Technology, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming 650500, China; 2. Key Laboratory of Animal Models and Human Disease Mechanisms of the Chinese Academy of Sciences & Yunnan Province, Kunming Institute of Zoology, Kunming 650223, China)

The tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri chinensis) is a small non-rodent mammal, which is a relatively new experimental animal in medicine due to its close evolutionary relationship to primates and its rapid propagation. Sperm characteristics and cryopreservation in the tree shrew were the main contents of our spermatological research. Epididymal sperm were surgically harvested from male tree shrews captured from the Kunming area. The rate of testis weight to body weight was (1.05±0.07)%, volume of both testis was (1.12±0.10) mL, total sperm from epididymis and vas deferens were 2.2−8.8×107, and sperm motility and acrosome integrity were (68.8±3.9)% and (90.0±2.1)%, respectively. Sperm ultrastructure of the tree shrew was examined by scanning electron microscopy and transmission electron microscopy. Tree shrew sperm had a round or oval shaped head of approximately 6.65×5.82 μm, and midpiece, principal piece, tail, and total sperm lengths were 13.39, 52.35, 65.74, and 73.05 μm, respectively. The mitochondria in the midpiece consisted of approximately 48 gyres and had a 9+9+2 axonemal pattern. After freezing and thawing, sperm showed partly intact acrosomes and plasma membrane defects, and sperm breakages, twists, and swellings were found. The tree shrew had similar ultrastructure with other mammalians except for the mitochondria number and the sperm size. Ultrastructural alteration is still the main cause resulting in poor sperm after cryopreservation.

Tree shrew; Testis; Sperm; Morphological structure; Cryo-damage

张远旭,男,硕士研究生,主要从事疾病动物模型研究

Q418; Q954.43

A

0254-5853-(2012)01-0029-08

10.3724/SP.J.1141.2012.01029

2011-11-01;接受日期:2011-12-31

国家自然科学基金(31071279)

∗通信作者(Corresponding author),E-mail: huashiyang@hotmail.com