线粒体蛋白酶LONP1结构、功能与相关疾病研究进展

[摘要] Lon蛋白酶是一种存在于细胞中的ATP依赖型蛋白酶,主要负责细胞内异常蛋白质的催化分解,以维持生物体内蛋白质的质量水平。Lon广泛参与细胞凋亡、细胞分化和DNA修复等细胞活动。近年来研究发现,哺乳动物细胞中的线粒体Lon(LONP1)异常表达与一系列疾病的发生发展相关,包括线粒体缺陷相关疾病、神经退行性疾病以及癌症等。鉴于LONP1活性的检测与调控对相关疾病的早期诊断和治疗的重要性,本文针对LONP1结构、功能、与相关疾病的关系、活性调控及检测方法作一系统综述。

[关键词] Lon蛋白酶;结构与功能;活性检测;功能调控;构效关系

[中图分类号] TQ617.3" [文献标志码] A" [文章编号] 1671-7783(2024)04-0354-10

DOI: 10.13312/j.issn.1671-7783.y230057

[引用格式]渠允薇,张世纪,张铎腾,等. 线粒体蛋白酶LONP1结构、功能与相关疾病研究进展[J]. 江苏大学学报(医学版), 2024, 34(4): 354-363.

[基金项目]国家自然科学基金资助项目(No. 22077101)

[作者简介]渠允薇(1996—),女,博士研究生;程夏民(通讯作者),副教授,硕士生导师,E-mail: ias_xmcheng@njtech.edu.cn;李林(通讯作者),教授,博士生导师,E-mail: ifelli@xmu.edu.cn

蛋白酶又称蛋白水解酶或肽酶,负责生物体内蛋白质的分解,从而调控相应的细胞功能。其中,蛋白酶体又称为自分隔蛋白酶,依赖于泛素蛋白酶体系统实现蛋白质降解的功能[1],主要存在于真核细胞胞膜以及胞核中[2]。蛋白酶体还广泛参与细胞活动,如细胞凋亡、细胞周期调节和DNA修复等[3-4]。在哺乳动物线粒体中,主要有3种依赖ATP的低聚物蛋白酶执行类似功能,即Lon、Clp-like和AAA蛋白酶[2,5]。其中,Lon是位于线粒体基质内的同源多聚体复合物[6],主要负责降解寿命短、折叠不良或受损的蛋白质[5,7],且维持线粒体基因组的稳定[8]。此外,Lon还具有结合线粒体DNA和蛋白伴侣的功能[8-10]。研究发现,Lon在氧化应激、缺血缺氧以及神经退行性疾病中均呈异常表达[11]。目前已知的人类Lon有线粒体Lon(LONP1)和过氧化物酶体Lon(LONP2)两种。鉴于LONP1活性检测与调控对相关疾病的早期诊断和治疗的重要性,本文针对LONP1结构、功能、与相关疾病的关系、活性调控以及检测方法作一全面综述。

1 Lon蛋白酶分类、结构与胞内定位

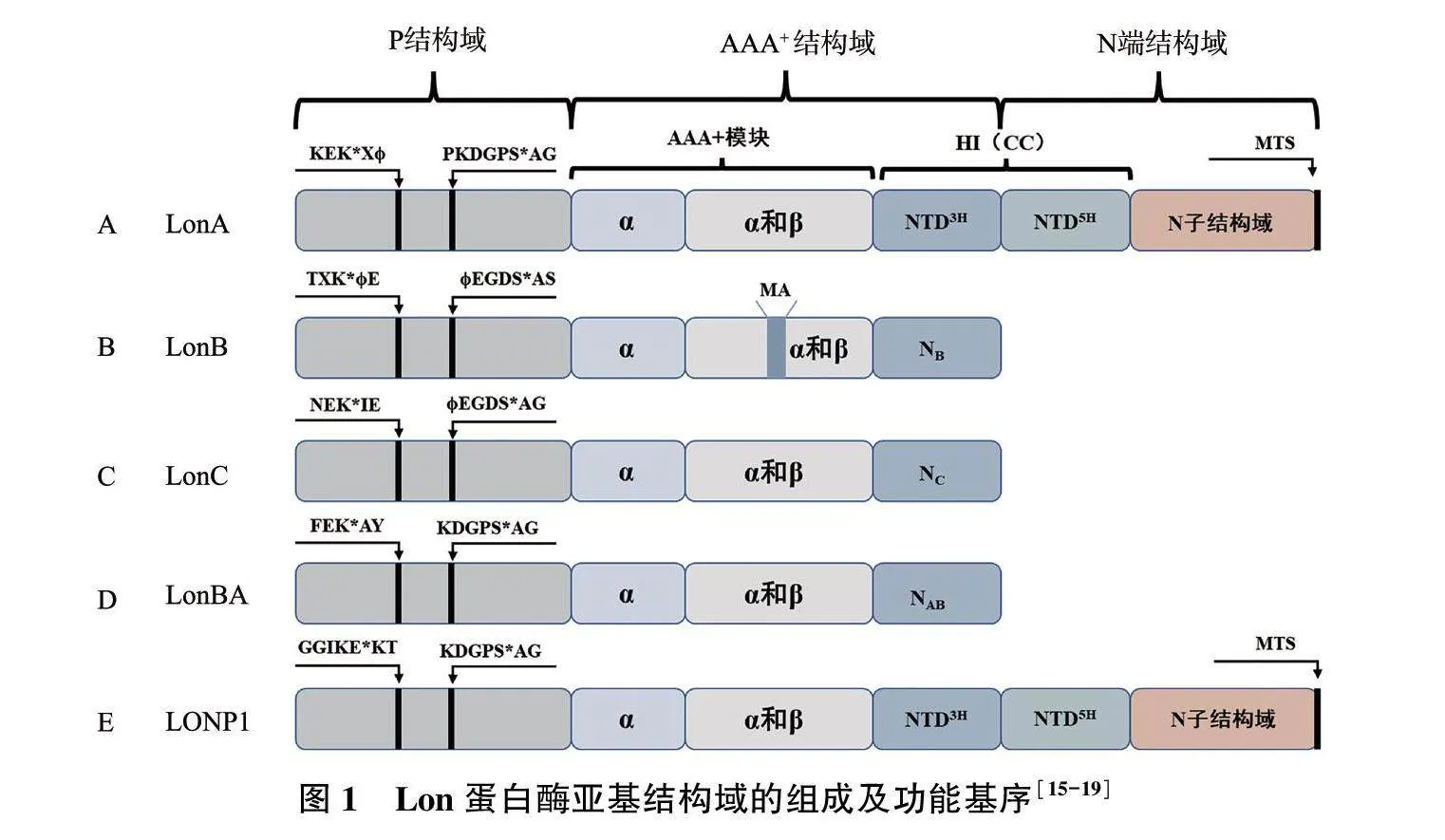

Lon蛋白酶的名称来源于大肠埃希菌Lon基因突变体表型[12]。大肠埃希菌同型寡聚Lon是第一个被鉴定的ATP依赖型蛋白酶,命名为EcLon;因其晶体结构已经完整解析,所以一直都是研究ATP依赖型蛋白酶的主要模型[13-14]。Lon蛋白酶家族所有Lon蛋白酶的多肽链均包含一个丝氨酸蛋白酶结构域(P结构域)以及参与核苷酸结合和ATP水解的Walker型ATP酶功能域(AAA+结构域),有的还包括一个扩展的线粒体基质靶向序列[N端结构域,包含具有盘旋螺旋(CC)构象的序列片段,图1][15-17]。根据对P结构域的晶体结构分析,Lon蛋白酶在MEROPS数据库中可以分为两个Lon蛋白酶亚家族:LonA(以大肠埃希菌Lon为代表)和LonB(主要存在于古细菌中)[18](图1A、1B)。随后在嗜热细菌中发现的Lon被归为第三个Lon亚结构,即LonC,其蛋白酶结构域和ATP酶功能域类似于LonB蛋白酶(图1C)[19]。最近,在枯草芽孢埃希菌中发现了LonBA,该蛋白酶具有LonA和LonB蛋白酶两者的结构特征,其蛋白酶活性中心属于A型(图1D)[15]。

由于LONP1表达与线粒体功能的维持密切相关,因此研究多集中于LONP1(图1E)。LONP1常以六聚体同源多聚体复合物形式存在,形成一个中空的环形结构,可以特异性地将底物包裹并催化水解[20]。LONP1由相应的LONP1基因(也称PRSS15)编码,位于19号染色体p13.2区域,长约29 000个碱基对。LONP1主要转录变体已在30多年前报道,该转录变体是一种约3.4 kb的mRNA[21]。LONP1编码的蛋白质含有956个氨基酸,每个单体分子量约106 kD,包含N端结构域、P结构域和AAA+结构域,这三个序列在进化中一直保持高度保守[21]。AAA+结构域由两部分组成,即ATP结合部分(α和β结构域)和ATP水解部分(α结构域)。LONP1水解活性的重要特征之一是受ATP刺激。P结构域携带丝氨酸和赖氨酸活性位点残基,形成催化二元组[22]。

2 LONP1功能

LONP1功能丰富,主要包括水解靶蛋白,结合线粒体DNA以及多种线粒体蛋白。因此,在维持线粒体功能方面发挥重要作用,并且成为疾病治疗的重要靶标。

2.1 LONP1作为蛋白酶的功能表现

作为蛋白酶,LONP1的重要功能是通过识别和降解被氧化修饰的蛋白质来维持线粒体的平衡[23]。在哺乳动物细胞中,通过遗传操作或完整生物体内的生理条件(氧化压力、老化等因素)下调LONP1表达,可导致线粒体内受损蛋白积累[7,24-25]。LONP1作用底物较为广泛,包括特异性和非特异性两种。其中,特异性底物包括乌头酸酶、δ-氨基乙酰丙酸合酶1(5-aminolevulinic acid synthase,ALAS-1)、类固醇合成急性调节蛋白(steroidogenic acute regulatory protein,StAR)、线粒体转录因子A(mitochondrial transcription factor A,TFAM)和细胞色素C氧化酶Ⅳ亚型1(cytochrome C oxidase 4 isoform 1,COX4-1)等。

LONP1首次在人类WI38/VA13肺成纤维细胞线粒体基质中发现,负责降解氧化的线粒体乌头酸酶[23,25-26]。乌头酸酶与线粒体mRNA翻译、氧化应激反应、铁代谢以及肿瘤抑制有关[27]。在衰老和某些与氧化应激有关的疾病中,乌头酸酶失活和积累是导致细胞功能紊乱和死亡的一个主要病理特征[28-29]。

ALAS-1是控制肝脏和骨髓细胞中血红素生物合成的第一速率控制酶[30]。研究表明,细胞内积累的血红素通过负反馈下调ALAS-1表达,该负反馈涉及转录抑制、mRNA降解和线粒体ALAS-1蛋白输入的阻断[31-33]。血红素积累可促进LONP1对线粒体基质中ALAS-1的依赖性降解,进而有助于调控血红素的生物合成[34]。

StAR是一种重要的核编码线粒体蛋白,介导类固醇激素合成的限制性步骤,在肾上腺皮质、胎盘和性腺细胞中,其经由LONP1降解[35]。StAR将胆固醇从线粒体外膜转移至线粒体内膜,继而胆固醇侧链裂解细胞色素的酶复合物将其转化为第一种类固醇孕烯醇酮[36]。在线粒体内,LONP1主要负责降解StAR,因此对LONP1进行调控可以调节类固醇激素的合成[35]。

TFAM是LONP1重要的底物之一[37]。TFAM是处于线粒体DNA复制、转录和遗传纽带上的高迁移率族蛋白,其直接调节哺乳动物线粒体DNA(mtDNA)的拷贝数[38-40]。LONP1通过调控TFAM降解进而调控DNA拷贝数和转录[37]。TFAM可经cAMP依赖性蛋白激酶磷酸化,从而损伤自身结合DNA和激活转录的能力,也可诱导LONP1对磷酸化TFAM的降解从而进行调节[40]。

COX4-1也受LONP1调节,其主要功能是催化线粒体的呼吸过程。在哺乳动物细胞中,COX4-1和COX4-2亚型表达受O2调节。缺氧诱导因子1(hypoxia inducible factor-1,HIF-1)是一种转录激活因子,可作为所有多细胞动物中氧稳态的主要调节剂[41]。HIF-1通过增加LONP1和COX4-2转录进而调控COX4亚单位的组成,并且HIF-1诱导LONP1过量表达可促进COX4-1降解。COX4亚单位表达的变化使得线粒体ATP生成、O2消耗和不同O2浓度下活性氧生成得到优化[41]。

2.2 LONP1作为mtDNA结合蛋白的功能表现

作为DNA结合蛋白,LONP1与mtDNA的结合相对保守[42-43]。LONP1结合特定的单链DNA,即轻链启动子非编码DNA和重链启动子编码DNA中的序列,两者都是启动mtDNA复制和转录的关键位点[43]。尽管LONP1在维持mtDNA和调节其拷贝数方面发挥作用,但确切的功能和机制仍不清楚。

2.3 LONP1作为蛋白伴侣的功能表现

作为蛋白伴侣,LONP1可以结合76种不同的线粒体蛋白,如热休克蛋白60(heat shock protein 60,HSP60)、结核杆菌热休克蛋白70(mycobacterium Tuberculosis heat shock protein 70,mtHSP70)和肌球蛋白等[44-45]。其中,HSP60和mtHSP70蛋白的稳定性与氧化应激时的表达水平相关;LONP1通过维持HSP60-mtHSP70蛋白复合物的稳定性进而调节细胞凋亡[44,46]。

3 LONP1表达异常与疾病的关系

LONP1表达异常如基因突变、表达水平上调或者下调,可引起一系列细胞功能异常和疾病。

3.1 LONP1基因突变与疾病的关系

1991年报道的脑、眼、牙、耳、骨骼异常(cerebral,ocular,dental,auricular,skeletal anomalies,CODAS)综合征是一种罕见的多系统发育障碍[47]。2015年,两个独立的团队分别证明了LONP1中杂合或纯合突变可导致CODAS综合征[48-49]。进一步对CODAS变体的结构分析发现,该病是由LONP1的AAA+结构域中的4种特定氨基酸经替换引起,进而导致底物特异性水解蛋白活性的缺陷以及线粒体形态和功能改变[48]。CODAS综合征的发现为因LONP1功能丧失进而危害机体健康提供了证据。

3.2 LONP1表达上调与疾病的关系

研究指出,线粒体脑肌病伴乳酸血症和脑卒中样发作(mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes,MELAS)综合征、肌阵挛性癫痫伴破碎样红纤维综合征(myoclonus epilepsy associated with ragged-red fibers,MERRF)与LONP1表达和活性改变有关[50-52]。mtDNA发生A3243G突变是MELAS最常见诱因,该突变的永生B细胞中LONP1表达水平增加,并且LONP1聚集于突变基因组和缺失复合物I(NDUFS3)所在的线粒体中[53]。同样,mtDNA的tRNALys基因中发生A8344G突变导致MERRF,其特点是LONP1表达增加,但活性降低,由此表明,在MERRF中,LONP1表达上调可能是对氧化损伤引起的酶活性降低的补偿[54]。

弗里德赖希共济失调(Friedreich′s ataxia,FRDA)是一种罕见的遗传性神经退行性疾病[55],染色体9q13纯合的GAA三核苷酸重复扩增导致共济蛋白基因的转录缺陷,最终导致线粒体共济蛋白表达量减少并形成FRDA[55]。在FRDA模型小鼠中,共济蛋白缺失可导致心脏变性、呼吸链复合物Ⅰ-Ⅲ和乌头酸酶缺乏以及线粒体铁蓄积[56]。在此情况下,LONP1表达上调与呼吸链酶缺乏相关,同时蛋白水解活性增强与复合物Ⅰ(NDUFS3)、复合物Ⅱ(SDHB)和复合物Ⅲ(Rieske)的Fe-S亚单位减少相关[57]。

缺氧、缺血/再灌注或缺血预处理可引发活性氧过度产生,进一步引发心肌细胞凋亡[58]。研究发现,缺氧诱导活性氧依赖性心肌细胞凋亡,而在缺氧诱导的心肌细胞中LONP1表达上调[59]。因此,LONP1表达下调可降低活性氧水平,从而缓解低氧诱导的心肌细胞凋亡[23]。此外,在常氧条件下,LONP1过表达可刺激活性氧的产生并诱导心肌细胞凋亡,调控LONP1表达具有治疗低氧诱导心肌细胞凋亡的潜在可能[59-60]。

LONP1在癌症中的作用包括维持肿瘤细胞在缺氧条件下的存活[41,60-61]、侵袭和转移[62]以及产生治疗抵抗[63]。不同于正常生理细胞,癌细胞中大部分来自葡萄糖的碳水化合物通过无氧糖酵解分解为乳酸,此即沃伯格效应(Warburg effect)[64]。HIF-1诱导糖酵解发生,癌细胞通过增强糖酵解为缺氧条件下肿瘤细胞的存活提供足够的ATP[60]。在此途径中,LONP1通过降解COX4-1异构体,从而在缺氧条件下维持细胞呼吸效率[41]。采用小鼠黑色素瘤B16F10细胞对LONP1在体内肿瘤形成和转移过程中的功能进行研究,结果表明,高水平LONP1是黑色素瘤预后不良的标志[62]。LONP1不但参与肿瘤细胞缺氧生存和代谢过程,还诱导修复mtDNA从而增强对放疗和化疗的抵抗[63]。此外,研究发现,LONP1在其他不同类型的人类癌症中表达上调[62,64-66]。因此,对细胞中LONP1活性进行检测和调控可能为癌症诊断与治疗提供一定的帮助。

3.3 LONP1表达下调与疾病的关系

PINK1是线粒体靶向丝氨酸/苏氨酸激酶,PINK1和Parkin基因功能的丧失或者突变可导致早发的常染色体隐性的帕金森病(Parkinson′s disease,PD)[67]。LONP1通过促进线粒体基质中PINK1的降解,在调节PINK1-Parkin通路中发挥重要作用[68]。PINK1在正常生理细胞中选择性地聚集在缺陷线粒体外膜,从而启动自身自噬降解[69-70]。LONP1表达下调致线粒体基质中被修饰后的PINK1在线粒体中急剧积累,从而激活体内的PINK1-Parkin途径,导致线粒体自噬无法正常进行从而引发PD[68]。

肌萎缩侧索硬化症(amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,ALS)是一种严重的神经退行性疾病[71],约10% ALS患者是家族性肌萎缩侧索硬化症(familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,fALS)。编码超氧化物歧化酶1(superoxide dismutase 1,SOD1)的基因突变是fALS中最常见的缺陷[72-73]。在表达突变G93A-SOD1基因的NSC34细胞(一种运动神经元样细胞系)中,LONP1表达下调[74]。由此表明,LONP1表达下调与fALS中运动神经元凋亡之间可能存在直接关系[74]。

内质网是膜和分泌蛋白实现正确折叠和寡聚化的细胞器[75]。体外缺血和体内缺氧均会诱发严重的内质网应激[76]。在培养的星形胶质细胞和脑缺血模型(大脑中动脉闭塞)的大鼠中,缺氧和缺血可分别诱导LONP1 mRNA和蛋白表达[77]。抵抗内质网应激需要激活蛋白激酶R样内质网激酶(protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase,PERK),同时蛋白质合成衰减,从而减少进入内质网的蛋白质,降低内质网负荷。在PERK(-/-)细胞中,内质网应激导致LONP1表达被抑制,证实LONP1参与内质网应激过程[77]。

4 蛋白酶活性调控与检测

抑制剂调控蛋白酶体(包括Lon在内)的活性是治疗相关疾病的一种重要手段,而活性检测是监测功能变化的重要手段之一。然而,目前只有少数广谱蛋白酶抑制剂可以抑制LONP1活性,其结构分析对于理性设计开发LONP1特异性抑制剂有一定的指导意义。

4.1 LONP1功能抑制

从结构而言,蛋白酶抑制剂可以简单地分为肽类抑制剂(图2)和非肽类抑制剂两大类(Pn为蛋白酶体抑制剂,Ln为Lon蛋白酶抑制剂)。

4.1.1 肽类抑制剂 大多数蛋白酶体抑制剂是含有活性基团的短肽,可与催化性N末端Thr1Oγ形成共价键(图3),如肽醛类(Ln1,图2)[78-79],多肽硼酸盐(Ln2amp;Pn1,图2)[80-81]和肽乙烯基砜(Pn2,图2)[82-83]。

肽醛MG132进入细胞后,可扩散至线粒体并抑制类固醇生成的StAR降解。由于Lon蛋白酶的水解活性类似于蛋白酶体,所以通过对市售肽类蛋白酶体抑制剂的筛选,发现蛋白酶体抑制剂MG262是肠道沙门氏菌中Lon蛋白酶的ATP依赖型抑制剂(Ln2,图2)[84]。

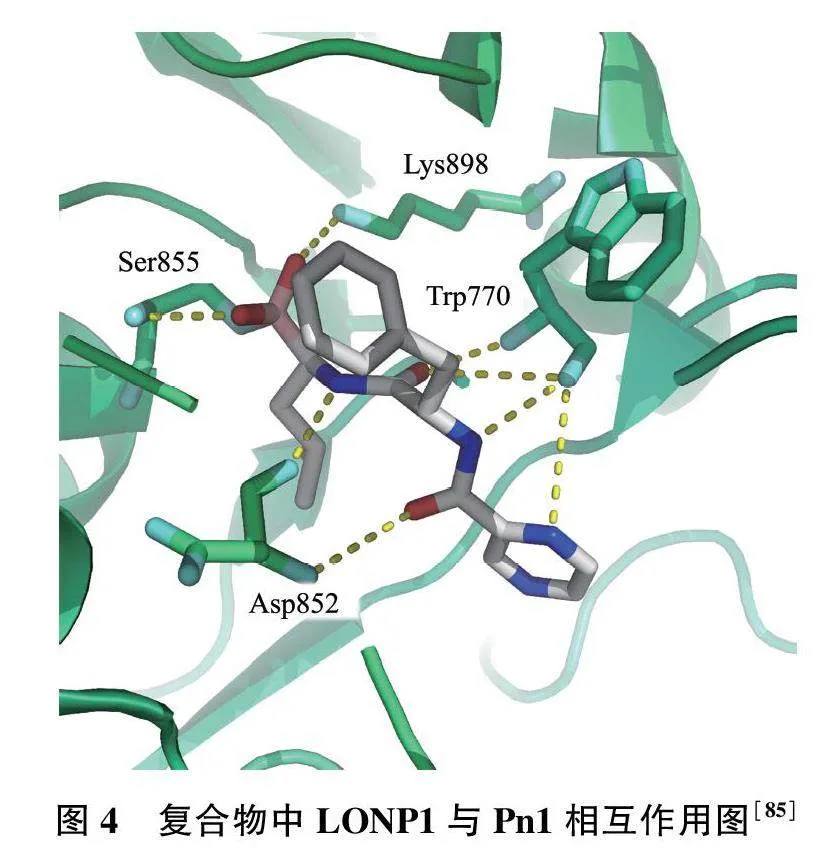

硼替佐米(Pn1)中硼原子与LONP1中Ser855羟基上的氧原子进行共价结合(图4),同时该分子上的氧原子和氮原子分别与Ser855、Lys898、Asp852和Trp770的氮原子和氧原子之间具有氢键作用力[85],由此大大提高Pn1与LONP1的结合能力。

4.1.2 非肽类抑制剂 1996年Pochet等[86]研究发现,香豆素衍生物可以抑制α-糜蛋白酶(α-chymotrypsin,α-CT)和人类白细胞弹性蛋白酶(human leukocyte elastase,HLE)活性(图5)。由于α-CT、HLE以及LONP1同属于丝氨酸蛋白酶,因此对于香豆素衍生物的筛选和结构优化有助于开发丝氨酸蛋白酶的特异性抑制剂[87]。2008年,Bayot等[88]在此基础上通过筛选香豆素衍生物,发现了可以特异性抑制LONP1活性的结构。综上所述,香豆素衍生物的结构对于开发LONP1特异性抑制剂,乃至抑制剂型荧光探针具有一定意义。香豆素衍生物是低分子量非肽类的高效多功能蛋白酶抑制剂。6-氯甲基-2-氧代-2H-1-苯并吡喃-3-羧酸的烷基(芳基酯、酰胺)是α-CT的高效抑制剂。结构与活性抑制结果的关系表明,苯环上取代基的位置显著影响化合物对丝氨酸蛋白酶的抑制作用[86]。邻位或间位取代是抑制效果较为明显的结构,其中间位取代衍生物Pn3[m-6-(氯甲基)-2H-1-苯并吡喃-3-甲酸酯]是该系列中效果最好的α-CT抑制剂(kinact/KI=762 700 M-1s-1,Pn3,图5)[86]。将Pn3中的苯酯替换为吡啶酯并且对6号位进行各种取代,研究表明,在没有6-氯甲基取代时,HLE通过形成短暂的酰基酶而被特异性抑制(Pn4,图5)[87]。

α-CT被6-氯甲基衍生物不可逆抑制(3b的kinact/KI=107 400 M-1s-1,Pn5,图5)。与此同时,研究结果也表明6号位的氯甲基是导致抑制剂通过自杀机制失活的必要条件。由此可知,通过调节取代基的结构和种类,香豆素衍生物可作为丝氨酸蛋白酶的广谱抑制剂或HLE的特异性抑制剂[87]。2008年,研究人员通过对5个香豆素化合物库进行筛选,并且分析了它们对酵母蛋白酶体的影响从而评估其对LONP1的特异性[Ln3(a-e),图5];结果显示,在37 ℃、pH=8条件下,化合物10 μmol/L Ln3(a-e)与0.4 mmol/L LONP1响应迅速,并呈时间依赖性,通过形成稳定的酰基酶而达到瞬时失活的状态(图3A)[88]。

早期研究发现,合成的三萜类化合物CDDO(2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9-dien-28-oic acid;Ln4,图6)及其衍生物通过一种与线粒体蛋白聚集相关的新型线粒体介导的途径促进B淋巴细胞凋亡[83];LONP1在人类B细胞淋巴瘤细胞系和患者衍生的样本中过表达,同时LONP1敲除可导致淋巴瘤细胞死亡[83]。研究者假设通过使LONP1水解功能失活,进而促进CDDO诱导的蛋白聚集和淋巴瘤细胞凋亡,一系列结果证明CDDO可以通过抑制LONP1的水解活性促进B淋巴细胞凋亡。由此表明,LONP1可能是一种新型抗癌药物靶点[83]。

2010年,研究人员从肉桂中提取了三桠乌药内酯A(Obtusilactone A,OA,Ln5,图6)和芝麻素[(-)-sesamin,Ln6,图6],在体外,这两种分子都可抑制重组Lon的活性。在活细胞中,OA导致乌头碱酶呈时间和剂量依赖性显著积累[89]。根据分子对接分析得知,OA和(-)-sesamin可与LONP1活性位点Ser855和Lys898残基结合而发挥作用(图7)。在LONP1表达水平较高的非小细胞肺癌细胞系中,OA或(-)-sesamin都可以下调LONP1表达,从而触发由Caspase-3介导的细胞凋亡[89]。

4.2 LONP1活性检测

目前,在各种疾病模型中,检测细胞内LONP1表达量应用最广泛的为依赖抗原抗体结合反应的生物学法,具体包括蛋白质印迹法[62]、PCR[66]以及特异性肽底物[90]等,但均操作烦琐、耗时费力,同时也无法用于活细胞检测。

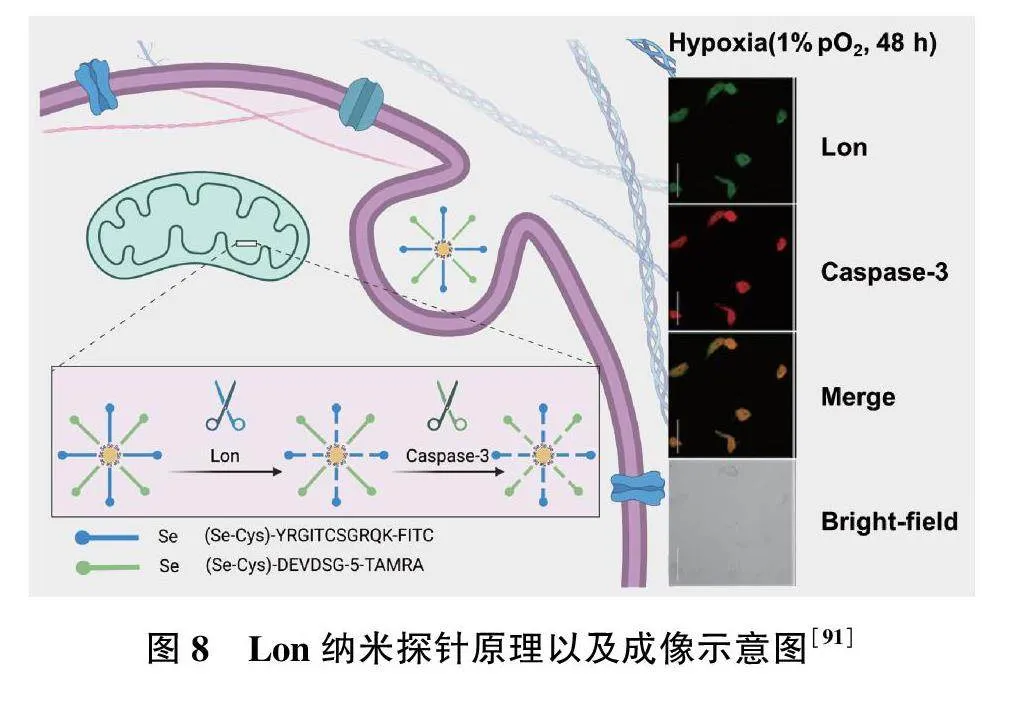

2021年,Zhan等[91]开发了一种检测大肠埃希菌Lon的纳米探针,分别用异硫氰酸荧光素(FITC)和5-羧基四甲基罗丹明(5-TAMRA)标记的硒醇修饰的肽链与纳米颗粒结合,使肽链分别在特定位点被Lon和Caspase-3水解,导致荧光团从金纳米颗粒的表面逃逸并伴随荧光增强(图8)。与此同时,该探针可以原位实时监测活体心肌细胞中LONP1和Caspase-3表达,已成功应用于LONP1-Caspase-3凋亡信号通路变化监测,以评估缺氧条件下心肌细胞的状态(图8)。此外,结合线粒体H2O2探针(MitoPY1),研究发现LONP1和活性氧对缺氧诱导的心肌细胞凋亡具有协同作用[91]。但是,纳米探针检测限较高,反应时间较长,无法在活细胞内定位LONP1等。因此,结合LONP1的反应活性位点、特异性反应基团及高亮度荧光团的研究,可为后续活细胞内LONP1的高时空分辨的荧光成像以及相关疾病的研究提供有效的分子工具。

5 总结与展望

综上所述,LONP1作为哺乳动物线粒体内对ATP具有依赖性的主要蛋白酶之一,其作用底物广泛,并在降解受损蛋白、维持线粒体基因组稳定性方面发挥重要作用,其表达异常与多种疾病密切相关。因此,LONP1的高效抑制和精确检测对相关疾病的预防、诊断和治疗具有重要意义。目前已报道的LONP1特异性抑制剂主要包括香豆素衍生物、三萜类化合物以及肉桂中提取物为主的非肽类抑制剂,开发高效的LONP1活性检测探针是未来研究其生物医学功能的重要方向之一。

[参考文献]

[1] Baumeister W, Walz J, Zuhl F, et al. The proteasome: Paradigm of a self-compartmentalizing protease[J]. Cell, 1998, 92(3): 367-380.

[2] Bulteau AL, Szweda LI, Friguet B. Mitochondrial protein oxidation and degradation in response to oxidative stress and aging[J]. Exp Gerontol, 2006, 41(7): 653-657.

[3] Dahlmann B. Proteasomes[J]. Essays Biochem, 2005, 41: 31-48.

[4] Bader N, Grune T. Protein oxidation and proteolysis[J]. Biol Chem, 2006, 387(10/11): 1351-1355.

[5] Escobar-Henriques M, Langer T. Mitochondrial shaping cuts[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, Mol Cell Res, 2006, 1763(5/6): 422-429.

[6] Leidhold C, Voos W. Chaperones and proteases-guardians of protein integrity in eukaryotic organelles[J]. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2007, 1113: 72-86.

[7] Bota DA, Ngo JK, Davies KJA. Downregulation of the human Lon protease impairs mitochondrial structure and function and causes cell death[J]. Free Radical Biol Med, 2005, 38(5): 665-677.

[8] Lu B, Yadav S, Shah PG, et al. Roles for the human ATP-dependent lon protease in mitochondrial DNA maintenance[J]. J Biol Chem, 2007, 282(24): 17363-17374.

[9] Liu T, Lu B, Lee I, et al. DNA and RNA binding by the mitochondrial Lon protease is regulated by nucleotide and protein substrate[J]. J Biol Chem, 2004, 279(14): 13902-13910.

[10] Suzuki CK, Rep M, van Dijl JM, et al. ATP-dependent proteases that also chaperone protein biogenesis[J]. Trends Biochem Sci, 1997, 22(4): 118-123.

[11] Bota DA, Davies KJA. Mitochondrial Lon protease in human disease and aging: Including an etiologic classification of Lon-related diseases and disorders[J]. Free Radical Biol Med, 2016, 100: 188-198.

[12] Amerik AY, Antonov VK, Gorbalenya AE, et al. Site-directed mutagenesis of La protease: A catalytically active serine residue[J]. FEBS Lett, 199 287(1/2): 211-214.

[13] Swamy KH, Goldberg AL. E. coli contains eight soluble proteolytic activities, one being ATP dependent[J]. Nature, 198 292(5824): 652-654.

[14] Vieux EF, Wohlever ML, Chen JZ, et al. Distinct quaternary structures of the AAA plus Lon protease control substrate degradation[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2013, 110(22): E2002-E2008.

[15] Wlodawer A, Sekula B, Gustchina A, et al. Structure and the mode of activity of Lon proteases from diverse organisms[J]. J Mol Biol, 202 434(7): 167504.

[16] Goldberg AL, Moerschell RP, Chung CH, et al. ATP-dependent protease La (lon) from Escherichia coli[J]. Methods Enzymol, 1994, 244: 350-375.

[17] Gustchina A, Li M, Andrianova AG, et al. Unique structural fold of LonBA protease from Bacillus subtilis, a member of a newly identified subfamily of Lon proteases[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 202 23(19): 11425.

[18] Rotanova TV, Botos I, Melnikov EE, et al. Slicing a protease: Structural features of the ATP-dependent Lon proteases gleaned from investigations of isolated domains[J]. Protein Sci, 2006, 15(8): 1815-1828.

[19] Liao JH, Kuo CI, Huang YY, et al. A Lon-like protease with no ATP-powered unfolding activity[J]. PLoS One, 201 7(7): e40226.

[20] Pomatto LC, Raynes R, Davies KJ. The peroxisomal Lon protease LonP2 in aging and disease: functions and comparisons with mitochondrial Lon protease LonP1[J]. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc, 2017, 92(2): 739-753.

[21] Wang N, Gottesman S, Willingham MC, et al. A human mitochondrial ATP-dependent protease that is highly homologous to bacterial Lon protease[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1993, 90(23): 11247-11251.

[22] Ondrovicova G, Liu T, Singh K, et al. Cleavage site selection within a folded substrate by the ATP-dependent lon protease[J]. J Biol Chem, 2005, 280(26): 25103-25110.

[23] Bota DA, Davies KJ. Lon protease preferentially degrades oxidized mitochondrial aconitase by an ATP-stimulated mechanism[J]. Nat Cell Biol, 200 4(9): 674-680.

[24] Levine RL. Commentary on “Downregulation of the human Lon protease impairs mitochondrial structure and function and causes cell death” by D.A. Bota, J.K. Ngo, and K.J.A. Davies[J]. Free Radic Biol Med, 2005, 38(11): 1445-1446.

[25] Bota DA, Van Remmen H, Davies KJ. Modulation of Lon protease activity and aconitase turnover during aging and oxidative stress[J]. FEBS Lett, 200 532(1/2): 103-106.

[26] Delaval E, Perichon M, Friguet B. Age-related impairment of mitochondrial matrix aconitase and ATP-stimulated protease in rat liver and heart[J]. Eur J Biochem, 2004, 271(22): 4559-4564.

[27] Sriram G, Martinez JA, McCabe ER, et al. Single-gene disorders: What role could moonlighting enzymes play?[J]. Am J Hum Genet, 2005, 76(6): 911-924.

[28] Lushchak OV, Piroddi M, Galli F, et al. Aconitase post-translational modification as a key in linkage between Krebs cycle, iron homeostasis, redox signaling, and metabolism of reactive oxygen species[J]. Redox Rep, 2014, 19(1): 8-15.

[29] Yan LJ, Levine RL, Sohal RS. Oxidative damage during aging targets mitochondrial aconitase[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1997, 94(21): 11168-11172.

[30] Podvinec M, Handschin C, Looser R, et al. Identification of the xenosensors regulating human 5-aminolevulinate synthase[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2004, 101(24): 9127-9132.

[31] Handschin C, Lin JD, Rhee J, et al. Nutritional regulation of hepatic heme biosynthesis and porphyria through PGC-1 alpha[J]. Cell, 2005, 122(4): 505-515.

[32] Zheng JY, Shan Y, Lambrecht RW, et al. Differential regulation of human ALAS1 mRNA and protein levels by heme and cobalt protoporphyrin[J]. Mol Cell Biochem, 2008, 319(1/2): 153-161.

[33] Dailey TA, Woodruff JH, Dailey HA. Examination of mitochondrial protein targeting of haem synthetic enzymes: in vivo identification of three functional haem-responsive motifs in 5-aminolaevulinate synthase[J]. Biochem J, 2005, 386(Pt 2): 381-386.

[34] Tian Q, Li T, Hou WH, et al. Lon peptidase 1 (LONP1)-dependent breakdown of mitochondrial 5-aminolevulinic acid synthase protein by heme in human liver cells[J]. J Biol Chem, 201 286(30): 26424-26430.

[35] Granot Z, Kobiler O, Melamed-Book N, et al. Turnover of mitochondrial steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein by lon protease: The unexpected effect of proteasome inhibitors[J]. Mol Endocrinol, 2007, 21(9): 2164-2177.

[36] Miller WL. Mitochondrial specificity of the early steps in steroidogenesis[J]. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, 1995, 55(5/6): 607-616.

[37] Matsushima Y, Goto Y, Kaguni LS. Mitochondrial Lon protease regulates mitochondrial DNA copy number and transcription by selective degradation of mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM)[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2010, 107(43): 18410-18415.

[38] Ekstrand MI, Falkenberg M, Rantanen A, et al. Mitochondrial transcription factor A regulates mtDNA copy number in mammals[J]. Hum Reprod, 2004, 13(9): 935-944.

[39] Bogenhagen DF, Rousseau D, Burke S. The layered structure of human mitochondrial DNA nucleoids[J]. J Biol Chem, 2008, 283(6): 3665-3675.

[40] Lu B, Lee J, Nie XB, et al. Phosphorylation of human TFAM in mitochondria impairs DNA binding and promotes degradation by the AAA+ Lon protease[J]. Mol Cell, 2013, 49(1): 121-132.

[41] Fukuda R, Zhang HF, Kim JW, et al. HIF-1 regulates cytochrome oxidase subunits to optimize efficiency of respiration in hypoxic cells[J]. Cell, 2007, 129(1): 111-122.

[42] Charette MF, Henderson GW, Doane LL, et al. DNA-stimulated ATPase activity on the lon (CapR) protein[J]. J Bacteriol, 1984, 158(1): 195-201.

[43] Fu GK, Markovitz DM. The human LON protease binds to mitochondrial promoters in a single-stranded, site-specific, strand-specific manner[J]. Biochemistry, 1998, 37(7): 1905-1909.

[44] Kao TY, Chiu YC, Fang WC, et al. Mitochondrial Lon regulates apoptosis through the association with Hsp60-mtHsp70 complex[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2015, 6(2): e1642.

[45] Desautels M, Goldberg AL. Demonstration of an ATP-dependent, vanadate-sensitive endoprotease in the matrix of rat liver mitochondria[J]. J Biol Chem, 198 257(19): 1673-1679.

[46] Deocaris CC, Kaul SC, Wadhwa R. On the brotherhood of the mitochondrial chaperones mortalin and heat shock protein 60[J]. Cell Stress Chaperones, 2006, 11(2): 116-128.

[47] Shebib SM, Reed MH, Shuckett EP, et al. Newly recognized syndrome of cerebral, ocular, dental, auricular, skeletal anomalies: CODAS syndrome-a case report[J]. Am J Med Genet, 199 40(1): 88-93.

[48] Strauss KA, Jinks RN, Puffenberger EG, et al. CODAS syndrome is associated with mutations of LONP encoding mitochondrial AAA+ Lon protease[J]. Am J Hum Genet, 2015, 96(1): 121-135.

[49] Dikoglu E, Alfaiz A, Gorna M, et al. Mutations in LONP a mitochondrial matrix protease, cause CODAS syndrome[J]. Am J Med Genet A, 2015, 167(7): 1501-1509.

[50] Pavlakis SG, Phillips PC, Dimauro S, et al. Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes: a distinctive clinical syndrome[J]. Ann Neurol, 1984, 16(4): 481-488.

[51] Montoya J, Playan A, Solano A, et al. Diseases of the mitochondrial DNA[J]. Rev Neurol, 2000, 31(4): 324-333.

[52] Shoffner JM, Lott MT, Lezza AM, et al. Myoclonic epilepsy and ragged-red fiber disease (MERRF) is associated with a mitochondrial DNA tRNA(lys) mutation[J]. Cell, 1990, 61(6): 931-937.

[53] Felk S, Ohrt S, Kussmaul L, et al. Activation of the mitochondrial protein quality control system and actin cytoskeletal alterations in cells harbouring the MELAS mitochondrial DNA mutation[J]. J Neurol Sci, 2010, 295(1/2): 46-52.

[54] Wu SB, Ma YS, Wu YT, et al. Mitochondrial DNA mutation-elicited oxidative stress, oxidative damage, and altered gene expression in cultured cells of patients with MERRF syndrome[J]. Mol Neurobiol, 2010, 41(2/3): 256-266.

[55] Koeppen AH. Friedreich′s ataxia: Pathology, pathogenesis, and molecular genetics[J]. J Neurol Sci, 201 303(1/2): 1-12.

[56] Rotig A, deLonlay P, Chretien D, et al. Aconitase and mitochondrial iron-sulphur protein deficiency in Friedreich ataxia[J]. Nat Genet, 1997, 17(2): 215-217.

[57] Guillon B, Bulteau AL, Wattenhofer-Donze M, et al. Frataxin deficiency causes upregulation of mitochondrial Lon and ClpP proteases and severe loss of mitochondrial Fe-S proteins[J]. FEBS J, 2009, 276(4): 1036-1047.

[58] Budinger GRS, Duranteau J, Chandel NS, et al. Hibernation during hypoxia in cardiomyocytes—Role of mitochondria as the O2 sensor[J]. J Biol Chem, 1998, 273(6): 3320-3326.

[59] Baehrecke EH. Autophagy: Dual roles in life and death?[J]. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2005, 6(6): 505-510.

[60] Kuo CY, Chiu YC, Lee AYL, et al. Mitochondrial Lon protease controls ROS-dependent apoptosis in cardiomyocyte under hypoxia[J]. Mitochondrion, 2015, 23: 7-16.

[61] Salceda S, Caro J. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1α) protein is rapidly degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system under normoxic conditions—Its stabilization by hypoxia depends on redox-induced changes[J]. J Biol Chem, 1997, 272(36): 22642-22647.

[62] Mazure NM, Pouyssegur J. Hypoxia-induced autophagy: cell death or cell survival?[J]. Curr Opin Cell Biol, 2010, 22(2): 177-180.

[63] Tangeda V, Lo YK, Babuharisankar AP, et al. Lon upregulation contributes to cisplatin resistance by triggering NCLX-mediated mitochondrial Ca2+ release in cancer cells[J]. Cell Death Dis, 202 13(3): 241.

[64] Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells[J]. Science, 1956, 123(3191): 309-314.

[65] Bernstein SH, Venkatesh S, Li M, et al. The mitochondrial ATP-dependent Lon protease: a novel target in lymphoma death mediated by the synthetic triterpenoid CDDO and its derivatives[J]. Blood, 201 119(14): 3321-3329.

[66] Liu YZ, Lan LH, Huang K, et al. Inhibition of Lon blocks cell proliferation, enhances chemosensitivity by promoting apoptosis and decreases cellular bioenergetics of bladder cancer: potential roles of Lon as a prognostic marker and therapeutic target in baldder cancer[J]. Oncotarget, 2014, 5(22): 11209-11224.

[67] Kitada T, Asakawa S, Hattori N, et al. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism[J]. Nature, 1998, 392(6676): 605-608.

[68] Jin SM, Youle RJ. The accumulation of misfolded proteins in the mitochondrial matrix is sensed by PINK1 to induce PARK2/Parkin-mediated mitophagy of polarized mitochondria[J]. Autophagy, 2013, 9(11): 1750-1757.

[69] Narendra D, Tanaka A, Suen DF, et al. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy[J]. J Cell Biol, 2008, 183(5): 795-803.

[70] Narendra DP, Jin SM, Tanaka A, et al. PINK1 is selectively stabilized on impaired mitochondria to activate Parkin[J]. PLoS Biol, 2010, 8(1): e1000298.

[71] Julien JP. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Unfolding the toxicity of the misfolded[J]. Cell, 200 104(4): 581-591.

[72] Rosen DR. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis[J]. Nature, 1993, 362(6415): 59-62.

[73] Deng HX, Hentati A, Tainer JA, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and structural defects in Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase[J]. Science, 1993, 261(5124): 1047-1051.

[74] Fukada K, Zhang FJ, Vien A, et al. Mitochondrial proteomic analysis of a cell line model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis[J]. Mol Cell Proteomics, 2004, 3(12): 1211-1223.

[75] Mori K. Tripartite management of unfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum[J]. Cell, 2000, 101(5): 451-454.

[76] Paschen W. Role of calcium in neuronal cell injury: Which subcellular compartment is involved?[J]. Brain Res Bull, 2000, 53(4): 409-413.

[77] Hori O, Ichinoda F, Tamatani T, et al. Transmission of cell stress from endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria: enhanced expression of Lon protease[J]. J Cell Biol, 200 157(7): 1151-1160.

[78] Groll M, Ditzel L, Lwe J, et al. Structure of 20S proteasome from yeast at 2.4 A resolution[J]. Nature, 1997, 386(6624): 463-471.

[79] Braun HA, Umbreen S, Groll M, et al. Tripeptide mimetics inhibit the 20 S proteasome by covalent bonding to the active threonines[J]. J Biol Chem, 2005, 280(31): 28394-28401.

[80] Adams J, Behnke M, Chen SW, et al. Potent and selective inhibitors of the proteasome: Dipeptidyl boronic acids[J]. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 1998, 8(4): 333-338.

[81] Adams J, Kauffman M. Development of the proteasome inhibitor VeleadeTM (Bortezomib)[J]. Cancer Invest, 2004, 22(2): 304-311.

[82] Bogyo M, McMaster JS, Gaczynska M, et al. Covalent modification of the active site threonine of proteasomal beta subunits and the Escherichia coli homolog HslV by a new class of inhibitors[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1997, 94(13): 6629-6634.

[83] Ovaa H, van Swieten PF, Kessler BM, et al. Chemistry in living cells: Detection of active proteasomes by a two-step labeling strategy[J]. Angew Chem Int Ed, 2003, 42(31): 3626-3629.

[84] Frase H, Hudak J, Lee I. Identification of the proteasome inhibitor MG262 as a potent ATP-dependent inhibitor of the Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium Lon protease[J]. Biochemistry, 2006, 45(27): 8264-8274.

[85] Shin M, Watson ER, Song AS, et al. Structures of the human LONP1 protease reveal regulatory steps involved in protease activation[J]. Nat Commun, 202 12(1): 3239.

[86] Pochet L, Doucet C, Schynts M, et al. Esters and amides of 6-(chloromethyl)-2-oxo-2H-1-benzopyran-3-carboxylic acid as inhibitors of alpha-chymotrypsin: Significance of the “aromatic” nature of the novel ester-type coumarin for strong inhibitory activity[J]. J Med Chem, 1996, 39(13): 2579-2585.

[87] Doucet C, Pochet L, Thierry N, et al. 6-substituted 2-oxo-2H-1-benzopyran-3-carboxylic acid as a core structure for specific inhibitors of human leukocyte elastase[J]. J Med Chem, 1999, 42(20): 4161-4171.

[88] Bayot A, Basse N, Lee I, et al. Towards the control of intracellular protein turnover: Mitochondrial Lon protease inhibitors versus proteasome inhibitors[J]. Biochimie, 2008, 90(2): 260-269.

[89] Wang HM, Cheng KC, Lin CJ, et al. Obtusilactone A and (-)-sesamin induce apoptosis in human lung cancer cells by inhibiting mitochondrial Lon protease and activating DNA damage checkpoints[J]. Cancer Sci, 2010, 101(12): 2612-2620.

[90] Lee I, Berdis AJ. Adenosine triphosphate-dependent degradation of a fluorescent lambda N substrate mimic by Lon protease[J]. Anal Biochem, 200 291(1): 74-83.

[91] Zhan RH, Guo WF, Gao XN, et al. Real-time in situ monitoring of Lon and Caspase-3 for assessing the state of cardiomyocytes under hypoxic conditions via a novel Au-Se fluorescent nanoprobe[J]. Biosens Bioelectron, 202 176: 112965.

[收稿日期] 2023-02-20" [编辑] 刘星星