乡村建筑师

摘 要 本文为关于建筑师及学术机构参与当代中国乡村振兴实践的研究。根据“政策—现象—结果”的分析框架,本文研究了过去20年来乡村振兴政策对建筑实践的综合影响。这项工作基于对中国乡村振兴的长期论述,特别关注建筑实践,以及学术界参与乡村实践的重新重视。通过分析现有的相关研究后,本文对乡村振兴的现象按照时间进行分类,并将建筑实践置于这一框架的核心位置。通过对乡村振兴框架下的乡村建筑实践进行系统研究,分析提出了3个不同的时期:开创阶段(1978—2003年)、成熟阶段(2004—2021年)和巩固阶段(面向2049年)。成熟阶段是本研究的核心,在这一阶段,发现两个主要轨迹:独立的建筑实践和学术机构对政策驱动的响应。本文选取了这些轨迹中的3个代表进行分析,分别是李晓东建筑实践、清华大学乡村振兴中心的相关工作和DnA设计与建筑工作室的独立实践。

关键词:乡村振兴;建筑师参与;机构参与;中国乡村

0 引 言

“A rural revival is needed to counter urbanization across the globe.”

“应对全球范围内的城市化进程需要乡村振兴”

——刘彦随,李玉恒[1]

随着世界对城市化和工业化的追求,农村衰落成为当代全球现象[2]。在全球化和城市化的框架下,乡村和城市的进步与提升呈现出繁荣与争议并存的双重性[3]。像中国这样一个国家,约880 万km2 [4] 的乡村土地是其文明的基础,占可利用土地的 92%,这种规模的乡村转变不容忽视。

在中国的过去30 年中,通过研究城乡比可以看出城市化进程的影响,以及人口由乡村地区向城市中心的大规模迁移。根据城乡居住总人口,中国统计年鉴报告称,2023 年乡村人口约占总人口的35%[5],与2001 年的64% 相比有显著下降[6]。观察1949—2012 年的城市化率,从10.6% 增加到52.6%[7],这一变化趋势更加明显。过去几十年,中国城市化进程和大规模基础设施建设无疑吸引了全球关注。与此同时,中国政府对乡村地区进行了重新定义,尽管其在全球范围的知名度较低[8]。过去40 年的改革开放和快速城市发展极大改变了城乡关系,而在过去的20 年中,乡村地区已从辅助角色和后备力量转变为区域发展中的重要组成部分和主要载体。因此,在过去的20 年中,重新考虑乡村发展和复兴策略,似乎是一个紧迫的全球性挑战,在国际讨论中具有重要的现实意义。乡村的发展面貌已经从促进城市化和工业化过渡到全面的城乡规划和综合措施管理[9],乡村地区的可持续发展再次受到关注。

在中国,设计和规划学科在重塑乡村面貌方面的重要性已得到认可,特别是在有争议的城乡二元结构中,近期的工作重点是振兴乡村建筑实践。目前,中国农村面临着三个主要问题:农业问题、农村问题和农民问题(三农问题)[10]。这些问题促进政策上的回应,推动和谐发展,这类政策旨在通过多学科合作的方法,促进创新方法的运用,以振兴乡村建筑实践。为实现这一目标,近年来中国出台了一系列战略,逐渐将重点从城市中心转向了“隐形的中国”。

从过去几年重新关注乡村背后的经济和政治原因,到在全国不同地区实施乡村振兴的政策和方法工具,不同学科的学者从不同角度对乡村振兴进行了研究。然而,很少有文章和研究关注乡村振兴与政策实施之间的直接关系,以及中国乡村振兴政策对乡村建筑实践的影响。因此,本研究旨在提供一个新的视角,考察过去20 年来乡村振兴政策对建筑实践的综合影响,重点关注建筑师和学术机构在这一过程中的参与情况。为此,本文在“政策—现象—效应”的框架内提出了一种分析方法,用于剖析政策影响的复杂层次、由此产生的乡村振兴现象,以及对建筑实践的后续影响。中国的建筑师们展现出丰富的专业知识,探索了各种方法论,挑战传统做法,并对一些根深蒂固的观念进行批判性评估。从利用当地材料和传统建筑技术,到与当地社区共同参与设计,建筑师的实践涵盖了一系列方法。重新考虑乡村的发展战略是一项紧迫的全球性挑战,在过去几十年里,它在国际上引起了很大的关注,成为政府、学者和学术机构研究的热点0。

1 当代中国的乡村振兴概况

1.1 中国乡村振兴介绍

关于乡村振兴,2017 年10 月18 日至24 日,中国共产党第十九次全国代表大会1 的顺利召开,标志着乡村振兴的概念首次上升到国家战略层面[11],也标志着中国农村的发展历程进入了一个开创性的时期。实施乡村振兴策略,是坚持农业农村优先发展,实现农业农村现代化的总目标,制定和完善促进城乡融合发展的框架、机制和政策体系的重要途径[9]。乡村振兴可以被视为乡村发展的第二阶段,从追求数量转向提升质量,并被认为对国家的全面复兴至关重要[12]。中国共产党第十九次全国代表大会后,党中央以全面推进乡村振兴为总目标,明确提出了农业农村优先发展的重大战略举措。缩小城乡社会经济差距,通过多层次目标体系实现城乡一体化,是实现中国乡村振兴战略的首要途径[13]。中国乡村振兴的本质在于加速农业和农村发展的现代化,涵盖5 个核心领域:企业蓬勃发展、宜居的生活环境、社会礼仪与文明、治理有效和生活富裕[14]。

尽管中国政府对乡村地区的关注自2017 年以来明显加大,但对乡村地区的关注不是最近才出现的现象。自中华人民共和国成立以来,有关乡村的政策一直在不断完善,与经济社会共同发展[15]。自21 世纪初以来,在乡村现代化的旗帜下,许多计划得到了推进2。在第十个五年计划期间,政府的经济战略将修订农村发展政策作为核心内容[16]。在“十五”计划即将结束之际,继农村发展政策之后,2005 年年底,中国共产党在第十六届中央委员会第五次全体会议中,在国家层面提出建设“社会主义新农村”的重大历史任务,将社会主义新农村建设放在经济社会发展工作的首位,并列为具体实施和实践的首要任务[17]。在该政策全国广泛实施之前,赣州在2004 年9 月开展了社会主义新农村建设,是中国第一个开展社会主义新农村建设的地级市,这一政策被称为“赣州模式”[18]。随后,全国人民代表大会于 2006 年 3 月正式批准了这一政策[19]。“农村综合改革要求我们围绕城乡一体化发展新格局,构建鼓励工业和城市带动农业和农村发展的体制和机制”3 [20]。根据这一政策,2004—2005 年期间,中国政府关于废除农业税的工作开始启动。2004 年,中国政府宣布将农业税降低1%,并在5 年内全面取消农业税[21]。自1949 年以来,农业税在支持国家工业化进程中发挥了重要作用[22]。2006 年1 月1 日,全国各省正式取消了农业税。这是农村角色转变的关键时期:从支持城市化和城市地区工业化的发展,到成为国家整体发展的重要组成部分。

1.2 2013—2021: 乡村振兴是农村政策的核心重点

乡村振兴政策是以往脱贫计划的延续[23],可视为乡村振兴的前提条件[24]。2013 年,中国政府以“党中央一号文件”提出了建设美丽乡村的目标,重点关注农村地区的可持续发展[17]。同年,中华人民共和国农业农村部启动了“美丽乡村”政府倡议,选择1000 个村庄作为试点[25]。这一举措的实施是一项重大成就,引起了公众的极大关注[26]。正如前文提到的,中国共产党第十九次全国代表大会的顺利召开,以及在此背景下宣布的“国家乡村振兴战略”,标志着中国乡村发展道路上的一个转折点。事实上,乡村振兴开始主导当年的政策,并成为有关乡村的核心话题。同年,中央农村工作会议于12月28 日至29 日在北京召开,会上提出了全面振兴乡村的计划,勾勒出乡村振兴蓝图,并规划了来年的发展计划。2018 年,在十九大指明方向后,中国政府发布了中共中央、国务院印发的《乡村振兴战略规划(2018—2022 年)》”。2021 年是中国共产党成立100 周年,这一重要时刻标志着宣布实现近年来设定的各项目标的关键节点。其中,扶贫工作在2017 年至2021年经历了“最后冲刺”阶段,并于2021 年被正式宣布彻底消除贫困。自1978 年以来,已有超过7.7 亿人摆脱贫困[27]。同年,中华人民共和国全国人民代表大会常务委员会颁布了《中华人民共和国乡村振兴促进法》4,为全面实施乡村振兴战略,促进农业、农村、农民全面进步,加快推进农业农村现代化提供了坚实的法治保障。2021 年,国家乡村振兴局成立,取代国务院扶贫办。

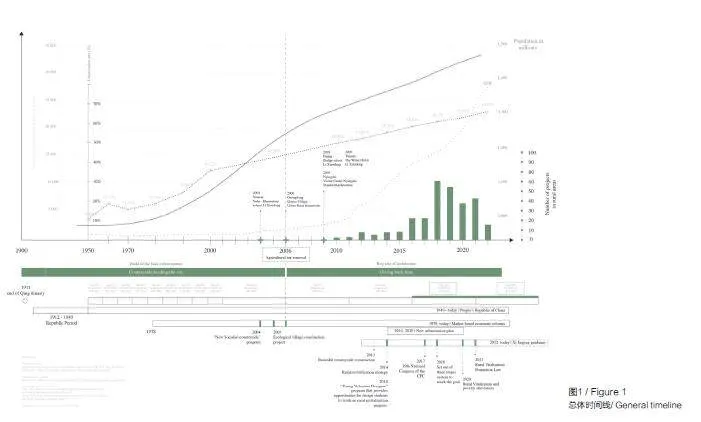

回顾关于乡村的学术研究,近几十年来,随着国内外学术界对乡村地区及其转型的研究表现出浓厚的兴趣,讨论的重点逐渐转向乡村。学术界对乡村的关注延伸到乡村振兴实践这一新兴领域,该领域近年来得到了显著的扩展。刘冷、曹聪杰和宋伟于2023 年, 对1991 —2021 年间发表的有关乡村振兴的现有文献进行了研究,研究显示,在分析的时间范围内,有3000 多名学者在乡村振兴领域发表了文章,其中 发表的文章集中2017—2021 年间,作者将这一时期定义为高产期[28]。当前的研究不再仅仅关注城乡二元对立,而是涵盖了旨在促进农村地区和谐与可持续发展的更广泛政策。然而,主要的研究领域通常集中在土地使用政策与管理、地理学、可持续发展,以及管理实施等主题上。值得注意的是,学术界对这些政策带来的建筑方面的影响缺乏关注。如下文阐述的,乡村振兴与乡村建筑实践的相互联系是一个重要的研究领域,值得更深入研究。从图1 中可以看出,建筑师参与乡村建筑实践的趋势与针对乡村发展的政策逐步推进有着密切关系。

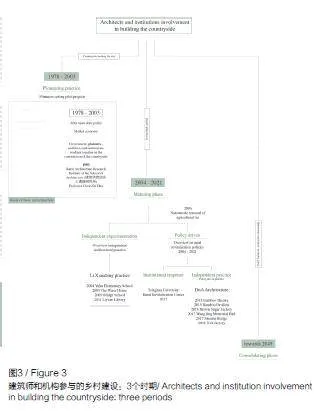

2 建筑师和学术机构参与乡村振兴:3 个阶段

中国政府实施的乡村振兴战略,代表了最新一系列致力于农村发展的政策[29]。中国发展研究基金会 (CDRF)5 根据政策变迁,将农村工作细分为3 个阶段:20 世纪80 年代的“激活”政策、20 世纪90 年代的“ 稳定” 政策和自2000 年年初起的“回馈农村”政策[30]。本研究将分析视角从政策驱动的年代细分,转向乡村建筑实践驱动的框架,提出一种与以往学者讨论框架略有不同的年代划分(图2),以建筑实践的时间线为核心。本研究侧重于分析建筑师和学术机构在乡村地区开展的工作,旨在理解导致不同时期之间转变的背景和政策。本文通过系统研究建筑师和学术机构在乡村振兴框架下的乡村建筑实践,将其分为3 个阶段(图3):开创阶段(1978—2003 年)、成熟阶段(2004—2021 年)和巩固阶段(2021—2049 年)。

2.1 开创阶段1978—2003 年

从20 世纪80 年代末开始,学术界对乡村的关注主要涉及乡土建筑的遗产保护。在陈志华教授的指导下,1993 年成立了清华大学建筑学院的乡土建筑研究所,致力于中国乡土建筑的研究。该课题组继承了梁思成、林徽因等学者注重传统建筑保护的传统,广泛考察了乡土建筑的历史、文化和地方特色。2023 年12 月,在乡土建筑研究所成立30 周年之际,“从乡土遗产到乡村振兴”学术研讨会在清华大学召开。会议讨论的重点从主要解决遗产保护问题过渡到改造现有建筑和建造新建筑。

2.2 成熟阶段2004—2021 年

成熟阶段是本研究的重点。从2004 年“社会主义新农村“计划开始,到2021 年中国共产党成立100 周年之际,“乡村振兴战略”和“扶贫攻坚战”取得重大进展。这一时期 通过创建社会主义新农村,把主要投向城市的公共资源更多地投向农村[31]。在此期间,农村地区的建筑项目显著增加,主要有两种轨迹:第一条轨迹被称为独立实践,时间跨度约为2004 —2011/2013 年,在此期间,城市规划者也参与了农村地区初级基础设施的建设;第二条轨迹被称为政策驱动实践,时间跨度为2013—2021 年,在这一时期,可以观察到建筑师对乡村振兴政策的响应,特别是2013 年制定的“美丽乡村建设”政策,以及2017 年出台的“乡村振兴战略”的进一步发展。这一时期建筑师开始大量参与乡村项目,导致此类工作大幅增加。政策驱动的轨迹引发了两种截然不同的回应:一方面是独立建筑实践的回应;另一方面是学术机构对这一现象的回应。

2.3 巩固阶段面向2049 年

2049 年是中华人民共和国建国100 周年,这对中国来说具有里程碑式的意义。考虑2049年的特殊意义,这一阶段设定了未来20 年内政策对乡村振兴的持续推动,将乡村振兴的道路设定为一个渐进过程,与到2049 年建设成为富强民主文明和谐的社会主义现代化国家的总体目标相一致[32]。实现乡村地区的全面振兴[33]。

3 建筑师和学术机构参与乡村振兴:2004—2021 年,成熟阶段

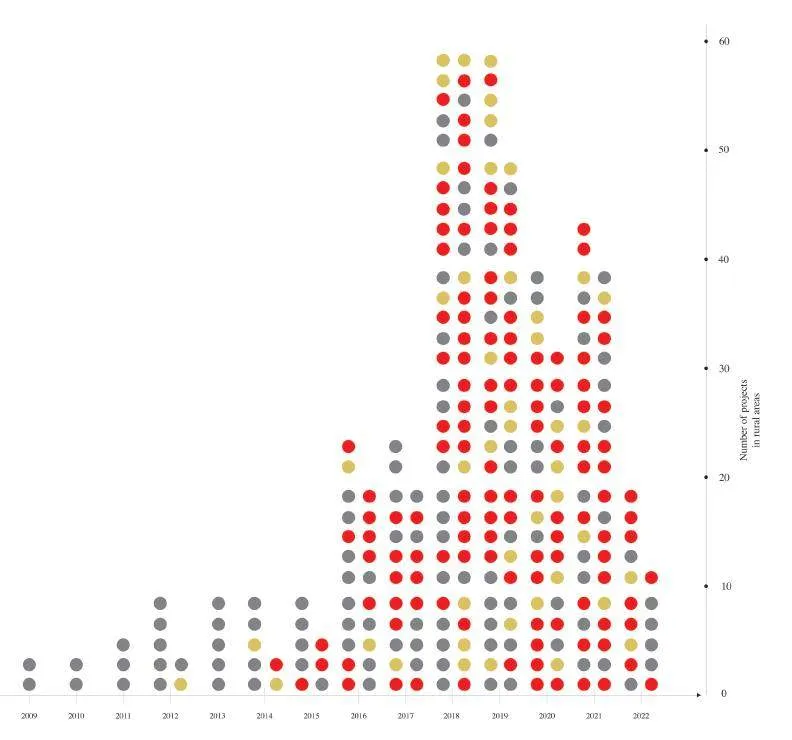

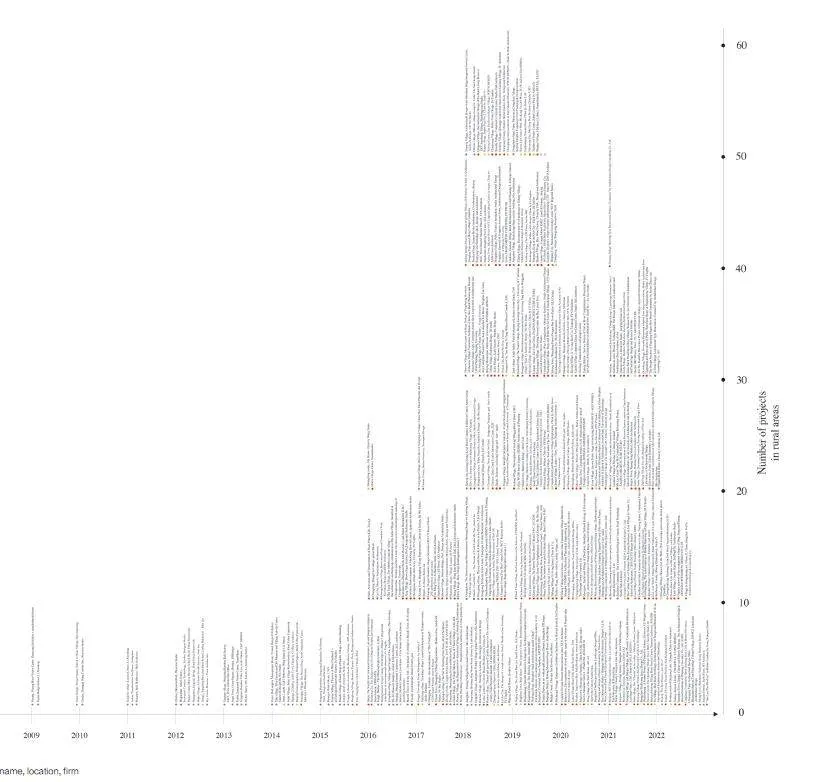

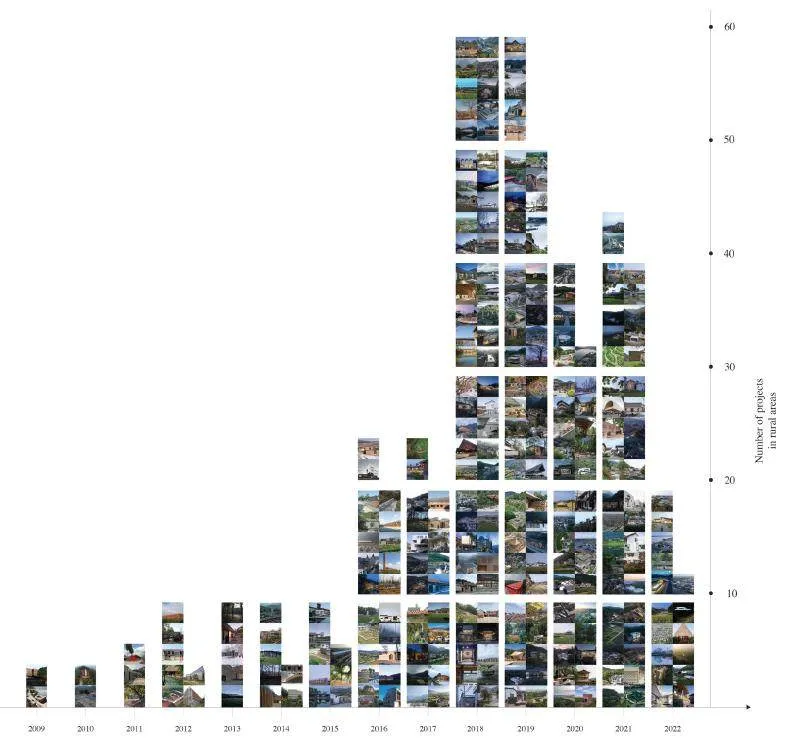

成熟阶段构成了本研究的核心焦点。建筑师的工作仍然是乡村振兴最具体的产出之一,丰富或改变了农村景观[25]。作者对过去20 年在中国农村地区实践的建筑师进行了系统分析,通过分析2000 —2022 年谷徳平台6 上发布的近300 个项目7,以“中国乡村重建”为主题词进行了筛选。选择该平台进行研究的原因:这是一个建筑领域的著名网站,以其在该领域的权威性和涵盖不同规模的建筑项目而闻名。在对过去20 年内以乡村振兴为重点的政策进行初步研究之后,作者对项目研究中获得的数据进行了交叉对比,揭示了乡村建筑实践与政策实施之间的相关性。从2015 年开始,与乡村振兴政策一致的乡村项目(图4,图5)急剧增加(图6), 并在2018—2019 年期间达到顶峰。在2018— 2019 年期间达到顶峰是意料之中的,这显然遵循了前文的推理:在2017 年提出乡村振兴战略后,乡村建筑实践迅速增加。此外,该分析在支持最初假设方面至关重要,即从2015年开始,很大一部分项目主要由地方政府委托进行(图 7),从而验证了过去10 年政策驱动的轨迹。

通过分析建筑生产,可以确定两条主要轨迹:第一条轨迹,作者称之为独立实践,大约从2004 年持续到2011—2013 年,该阶段见证了独立建筑师在农村地区承担单一任务的建筑实践,明确的案例包括李晓东早期在农村的项目(2003 年的玉湖小学,2009 年福建省的桥上小学,2011 年交界河村的篱苑书屋),以及乡村城市框架的项目(2006 年的秦磨村,2011 年怀集县的木兰小学,2012 年陕西的岭子底村便民桥,2012 年的同江村循环再用砖学校等)。在这一阶段早期,即建筑师下乡浪潮之前,规划师参与了农村地区的初级基础设施、道路系统和一些公共设施的建设,并设立了试点项目,这些项目的范例随后在全国范围内推广。此趋势的代表性案例是位于北京城市扩张区的试点项目,由张悦8、倪锋9 所领导的团队在顺义区实施,该项目获得2008 年亚太区豪瑞10 金奖,以及次年的全球豪瑞铜奖。第二条轨迹被称为政策驱动的实践,包涵2013—2021 年时期。在此时期,建筑领域对乡村振兴政策作出了回应。建筑师们开始大规模参与乡村建筑实践,导致此类项目显著增加。政策驱动的轨迹引发了两种截然不同的响应:一方面是独立建筑实践的回应,表现为政府委托数量的不断增加;另一方面是学术机构对这一现象的回应。

伴随着国家政策发展的轨迹,实施乡村振兴战略的学术响应是一个值得注意的现象。实际上,自2017 年起,各大高校在乡村建筑实践中的逐步参与便已显现。在这一实践中,清华大学属于先锋之一,该校于2017 年10 月,响应全国代表大会的号召,设立了乡村振兴中心,作为与地方政府合作,在全国不同省份建立工作站的模范。2021 年2 月23 日,中共中央办公厅、国务院办公厅印发了《关于加快推进乡村人才振兴的意见》,2022 年又印发了《乡村建设行动实施方案》,将乡村建设作为实施乡村振兴战略的重要任务和国家现代化建设的重要组成部分[34]。2021 年12 月,由清华大学发起,19 所高校成立了“乡村建设高校联盟”,该联盟作为高校共同助力乡村振兴、发展和服务乡村现代化的合作机制,吸引了更多高校参与乡村建设[35]。继上述行动之后,2022 年9 月7 日,由国家乡村振兴局与清华大学共同推动的“百校百县千村”行动开始启动,鼓励各大高校积极参与乡村建设和乡村振兴[36-37]。

在对参与这一过程的建筑师和学术机构进行全面概述之后,本研究将重点工作放在这些轨迹的3 个相关代表上。李晓东的建筑实践是乡村项目的先锋力量,体现了过去20 年中最早的乡村独立实践。在政策驱动的轨迹中,清华大学乡村振兴中心被评选为响应政策实施范例最具代表性的机构,而 DnA 设计与建筑工作室的实践则被评选为独立政策驱动实践的典范。

3.1 独立实践: 李晓东的建筑实践

中国乡村自发项目的先锋无疑是李晓东。李晓东(1963 年生于北京)于1984 年毕业于清华大学建筑学院,并于1989 年至1993 年在荷兰代尔夫特理工大学建筑学院获得博士学位。他的实践主要集中在小规模的项目上,对场地有很强的整体性,将当代建筑与地域文化融为一体。李晓东在2000 年年初开始下乡实践时,中国建筑界主要是由开发商设计和建造的大型城市项目。与城市建筑行业的高约束相比,乡村项目几乎没有太多限制,为独立建筑师提供了在小型项目中进行实践的机会。他完成的第一个项目象征着对乡村地区重新关注的开始,即丽江玉湖小学扩建项目11。该项目位于海拔接近2800 米的云南丽江玉湖村,该区域自1997年12 月起被列为世界文化遗产保护区12。当时,村里的小学于2001 年刚刚建立,但由于无法满足教育需求,急需扩建。李晓东的乡村建筑实践一直持续到2011 年,之后他将实践方向转向了城市。2009 年,福建省下石村的桥上小学,不仅在设计方面,而且在类型学方面都实现了突破:它是第一座将学校和桥梁的类型学结合在一起的建筑。该建筑长28m,宽8.5m,突破了连接溪流两岸的传统桥梁类型和场地内现有的土地类型。李晓东将实践注意力转移到城市前,在农村完成的最后一个项目是篱苑书屋。该项目位于北京市怀柔区的交界河村,建于2011 年,是第一个在乡村建造的图书馆,之后又有许多项目沿用了这一类型。李晓东在乡村的建筑实践获得了国际认可,并赢得了众多奖项。

3.2 政策驱动实践

3.2.1 学术机构回应:清华大学与乡村振兴中心

清华大学无疑是学术机构参与乡村振兴实践的先行者。2017 年10 月,伴随着国家政策发展的趋势,响应党的十九大提出的“乡村振兴战略”号召,清华大学成立了乡村振兴中心。乡村振兴中心最初由清华大学建筑学院发起,7 年来,在校党委的指导下,在清华大学校党委和团委的支持下,多部门合作开展项目。乡村振兴中心共组织了460 多个团队,由来自200 多所高校100 多个学科的7000 多名师生组成[38]。在选定的乡村建立工作站,为学生在乡村建立永久性基地,倡导“以实践为基础”的校地合作实践育人模式,为社会实践提供新的可能。每年寒暑假,来自不同院系和众多附属大学的学生都有机会到偏远的乡村去,贡献他们在不同领域的知识和专长。

3.2.2 独立实践回应:DnA 设计与建筑工作室

徐甜甜于2004 年在北京创建的DnA 设计与建筑工作室,无疑是当代中国在乡村振兴领域最具影响力和国际知名度的工作室之一。与中国各大城市因快速城市化而趋于标准化的建筑景观不同,DnA 设计与建筑工作室的设计方法将注意力重新转移到对当地材料、资源和技术的利用上,包括采用传统的手工建造方法,这些方法往往被城市中心典型的快速发展所边缘化。纵观该事务所2015—2022 年的建筑作品,可以发现大部分项目都集中在浙江省西南部,丽水市下辖的松阳县。该地区被定义为“最后的江南秘境\", 松阳县全面保留了70 个传统村落,探索以文化为引领的乡村复兴路径[39]。徐甜甜在该地区实施了约20 个项目,通过小规模的干预,使乡村重建超越了单一的建筑设计,促进该地区的多尺度增长。徐甜甜的方法很明确:将建筑针灸作为一种可持续的乡村战略。通过最小干预的设计,将公共项目引入村庄,每个项目都尊重文化遗产和文脉[40]。对该地区各种项目背后的客户进行研究后发现,这些项目主要由地方政府委托实施。这一观察结果证明了最初的假设,即在乡村地区开展的项目增加与为乡村地区制定的振兴政策之间存在联系。

4 结 语

总之,乡村振兴在当代中国扮演着举足轻重的角色,包括建筑范围的学术机构和独立实践。近期的研究主要关注政策框架,忽视了这些转型对建筑环境的影响。本研究强调了过去二十年来建筑师和学术机构在中国乡村所扮演的角色,旨在丰富当前关于乡村振兴的讨论,同时提出了以建筑实践为重点的时期划分。研究建议按时间顺序划分为开创阶段、成熟阶段和巩固阶段,有助于人们对这些实践的演变和影响有更细致的理解。通过考察李晓东、清华大学乡村振兴中心、DnA 设计与建筑工作室等实践案例,本研究证实了建筑在促进乡村振兴方面所走过的多样化但又趋同的道路。

注释

0 文章《乡村建筑师 :建筑师及学术机构参与中国乡村振兴的分析》是作者博士论文(2020 年至今)其中一章的改编。该博士论文研究基于“全球化的跨国建筑模式”的联合博士课程框架。该联合博士课程为都灵理工大学的历史与项目和清华大学的建筑、城乡规划和景观设计。

本文提出的时期划分提供了一个总体框架,旨在说明中国农村建筑实践的总体趋势。然而,我们必须承认这种时期划分的局限性。在所分析的时间段内,中国各地区的社会经济发展并不平衡,导致不同地区的乡村发展程度存在显著差异。由于中国地域广阔,各地区经济发展水平参差不齐,根据具体情况和地区的不同,建议的时期划分起止日期可能存在较大差异。因此,在这一时期划分中提出的日期应被视为总体趋势的指示性日期,而不能被解释为绝对的截止日期。

The article “The Countryside Architect: An Analysisof Architects and Academic Institutions Involved inChina’s Rural Revitalization” represents the adaptationof one of the chapters of the Author’s Ph.D. thesis(2020 – ongoing). The Ph.D. research is conducted inthe framework of the Joint Ph.D. curriculum named“Transnational Architectural Models in a GlobalizedWorld” within the framework of the Doctoral Program inArchitecture. History and Project at Politecnico di Torinoand the Doctoral Program in Architecture, Urban andRural Planning, and Landscape Architecture at TsinghuaUniversity in Beijing.

The periodization proposed in this article, as presented,provides a general framework aimed at illustrating theoverall trends in architectural practices in rural China.However, it is important to acknowledge the limitationsof this proposed periodization. The social and economicdevelopment across different regions of China was unevenduring the analyzed timeframe, resulting in significantdifferences in the degree of rural development acrossdifferent areas. Given the vastness of the country and thevarying levels of economic development across regions,the indicative starting and ending dates of the proposedperiodization might differ considerably depending on thespecific context and regions. The dates proposed in thisperiodization should, therefore, be regarded as indicativeof an overall trend, with the end date, which is not to beinterpreted as absolute.

1 2017 年10 月18 日至24 日,中国共产党第十九次全国代表大会在北京召开。

The 19th Party Congress was held in Beijing fromOctober 18–24, 2017.

2 21 世纪初以来,颁布或实施的与乡村地区相关的政策数量庞大。由于作者不具备对其进行详尽分析的学术背景,因此该部分仅代表作者认为与研究背景相关的政策,特别是对建筑师和学术机构参与乡村建设相关的政策。

or implemented since the beginning of the 21st centuryare numerous. Since the author does not possess theacademic background to analyze them exhaustively, thisparagraph reports those that the author considers relevantto the initial hypothesis and specifically related to theeffect of the policies on the involvement of architects andacademic institutions in building the countryside.

3《中国浙江:发展新愿景》收录了习近平 2003 —2007 年为浙江日报“中国浙江:发展新愿景”专栏撰写的232 篇文章。该文集已由外文出版社以多种语言出版。

The volume “Zhejiang, China: A New Vision forDevelopment” collects the 232 essays written by XiJinping for the column “Zhejiang, China: A New Visionfor Development” of Zhejiang Daily between 2003 and2007. The collection of essays has been published by Foreign Languages Press in multiple languages.

4 2021 年4 月29 日第十三届全国人民代表大会常务委员会第二十八次会议通过,自2021 年6 月1 日起施行。

Adopted at the 28th Meeting of the Standing Committeeof the Thirteenth National People’s Congress on April29th, 2021, and came into effect on Jun. 1st, 2021.

5 中国发展研究基金会(CDRF)注册于 1997 年,是由国务院发展研究中心(DRC)发起成立的公募基金会。

Registered in 1997, The China Development ResearchFoundation (CDRF) is a public foundation initiated bythe Development Research Center of the State Council(DRC).

6 作者承认这项研究具有一定片面性,但它在提供了足够广泛的统计样本(分析了 300 多个项目),以阐明过去20 年农村地区建筑实践的主要趋势和在发展轨迹方面的作用。作者提供的图纸可能存在误差。

The author acknowledges the study’s partiality whilerecognizing its utility in providing a sufficiently extensivestatistical sample (with almost 300 projects analyzed) toelucidate key trends and the trajectory of architecturalpractices in rural areas over the past two decades.Accidental inaccuracies in the drawings provided by theauthor may occur.

7 gooood 是一家在建筑、景观设计、室内设计和艺术领域具有影响力的在线杂志,总部位于北京。它是建筑领域访问量最高的网站之一,在中国排名第一(全球建筑类网站排名前三,位居中国和亚洲建筑网站榜首)。说明来自官方网站https://www.gooood.cn/aboutus。

gooood is an influential online magazine in the field ofarchitecture, landscape, design, interior design, and art.Based in Beijing, gooood is a top-ranked website in thefield of Architecture which has the highest traffic in China(one of the top 3 architecture sites in the world; 1st rankin top architecture sites in both China and Asia). Officialwebsite. https://www.gooood.cn/aboutus.

8 张悦教授现任清华大学建筑学院城市规划系副主任。他于2003 年获得清华大学城市规划与设计专业博士学位。张悦教授曾获得2009 年全球豪瑞铜奖和2008 年亚太地区豪瑞金奖,获奖项目为中国北京的农村社区可持续规划。他还凭借“最小化最大化:中国北京白塔寺城市更新”项目获得了2017 年豪瑞奖。

Professor Zhang Yue is Professor amp; Vice Chair of theDepartment of Urban Planning at the School of Architecture,Tsinghua University, in Beijing, China. He obtained hisPhD in 2003 in Urban Planning and Design at TsinghuaUniversity. Professor Zhang Yue was the winner of theGlobal Holcim Awards Bronze 2009 and Holcim AwardsGold 2008 Asia Pacific for Sustainable planning for arural community, in Beijing, China. He also won a HolcimAwards Acknowledgement in 2017 for Maximize theMinimum: Baitasi urban regeneration in Beijing, China.

9 倪锋,北京市城市规划委员会。

Feng Ni, Beijing Municipal Commission of UrbanPlanning.

10 豪瑞奖是一项国际竞赛奖项,旨在表彰和推广可持续建筑和设计方面的创新项目和理念。该奖项由豪瑞可持续建筑基金会主办。

The Holcim Award is an international competition thatrecognizes and promotes innovative projects and conceptsin sustainable construction and design. It is organized bythe Holcim Foundation for Sustainable Construction.

11 玉湖小学和社区中心是新加坡国立大学设计与环境学院建筑系的研究与设计项目,时间为2002 至2004 年, 项目团队包括: 李晓东博士、Lim Guanxiong 博士, Yeo Kang Shua, Cheong Kenghua。

The Yuhu Primary School and Community Center isa research and design project by the Department ofArchitecture, School of Design and Environment.National University of Singapore 2002-2004.Project team: Dr Li Xiaodong, Dr Lim Guan Tiong, YeoKang Shua, Chong Keng Hua.

12 丽江古城于 1997 年被列入联合国教科文组织遗产名录。

The old town of Lijiang was inscribed in the UNESCOheritage sites in 1997.

参考文献

References

[1] LIU Y S, LI Y H. Revitalize the world’s countryside[J].Nature, 2017, 548(7667): 275-277.

[2] LI Y H, YAN J Y, SONG C Y. Rural revitalizationand sustainable development: typical case analysis and itsenlightenments[J]. Geographical Research, 2019, 38(3):595-604.

[3] ZHANG X, Li X. Rural Futures: Challenges andOpportunities in Contemporary China[M]//Li X, Mo W,Rebecca Gros. Building a future countryside. New York:The Images Publishing Group / ACC Art Books, 2018.

[4] World Bank Open Data. World Bank open data[EB/OL].[2024-02-22]. https://data.worldbank.org.

[5] National Bureau of Statistics. China statistical yearbook2023[M]. Beijing: China Statistical Publishing House, 2023.

[6] National Bureau of Statistics. China statistical yearbook2001[M]. Beijing: China Statistical Publishing House, 2001.

[7] LI Y H, WESTLUND H, ZHENG X Y, et al. Bottomupinitiatives and revival in the face of rural decline: casestudies from China and Sweden[J]. Journal of Rural Studies,2016, 47: 506-513.

[8] PETERMAN S. Villages with Chinese Characteristics[M]//AMO, KOOLHAAS R. Countryside, A Report.Cologne: TASCHEN, 2020: 124-147.

[9] WEN Q, ZHENG D Y, SHI L N, et al. Themes evolutionof rural revitalization and its research prospect in China from1949 to 2019[J]. Progress in Geography, 2019, 38(9): 1272-1281.

[10] ZHOU G H, LONG H L, LIN W L, et al. Theoreticaldebates and practical development of the “three rural issues”and rural revitalization in the New Era[J]. Journal of NaturalResources, 2023, 38(8): 1919-1940.

[11] XIU J H. The restrictive factors of rural revitalizationand its breakthrough methods[C]//Proceedings of the4th International Conference on Economy, Judicature,Administration and Humanitarian Projects. Kaifeng, China:Atlantis Press, 2019: 819-823.

[12] GENG Y Q, LIU L W, CHEN L Y. Rural revitalizationof China: a new framework, measurement and forecast[J].Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 2023(89): 10-16.

[13] LIU Y S, ZANG Y Z, YANG Y Y. China’s ruralrevitalization and development: theory, technology andmanagement[J]. Journal of Geographical Sciences, 2020,30(12): 1923-1942,

[14] YANG X J, LI W W, ZHANG P, et al. The dynamicsand driving mechanisms of rural revitalization in WesternChina[J]. Agriculture, 2023, 13(7): 1448.

[15] ZHANG D S, GAO W, LV Y Q. The triple logic andchoice strategy of rural revitalization in the 70 years sincethe founding of the People’s Republic of China, based onthe perspective of historical evolution[J]. Agriculture, 2020,10(4): 125.

[16] SU M. New Rural Development Strategies[M]//SUM. China’s rural development policy: exploring the “newsocialist countryside”. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers,2009.

[17] WANG J H. Building a new socialist countryside[M]//CHEN X W, WEI H K, SONG Y P. Rural Revitalization inChina. Singapore: Springer, 2023: 121-144.

[18] LOONEY K E. China’s campaign to build a newsocialist countryside: village modernization, peasantcouncils, and the Ganzhou model of rural development[J].The China Quarterly, 2015(224): 909-932.

[19] AHLERS A L, SCHUBERT G. “Building a newsocialist countryside” - only a political slogan?[J]. Journal ofCurrent Chinese Affairs, 2009, 38(4): 35-62.

[20] XI J. Energize rural areas through reform[M]//XI J.Zhejiang, China: a new vision for development. Hangzhou:Foreign Languages Press, 2019:322-323.

[21] WANG X X, SHEN Y. The effect of China’sagricultural tax abolition on rural families’ incomes andproduction[J]. China Economic Review, 2014(29): 185-199.[22] LIN J Y, LIU M X. Rural informal taxation in China:historical evolution and an analytic framework[J]. China amp;World Economy, 2007, 15(3): 1-18.

[23] DENG W. An analysis of rural area revitalizationstrategy from the perspective of economic law[J]. BeijingLaw Review, 2023, 14(2): 1056-1078.

[24] SU M, YUAN M Y, MA X J, et al. The organicconnection of rural revitalization and poverty alleviationfrom the perspective of spillover effect[J]. InternationalJournal of Education and Humanities, 2022, 5(2): 176-185.[25] ZHANG X C. Beautiful villages: rural constructionpractice in contemporary China[M]. HE Y F, trans.Mulgrave: Images Publishing, 2018.

[26] JI Q, YANG J P, HE Q S, et al. Understanding publicattention towards the beautiful village initiative in Chinaand exploring the influencing factors: an empirical analysisbased on the Baidu index[J]. Land, 2021, 10(11): 1169.

[27] World Bank, Development Research Center of the StateCouncil, the People’s Republic of China. Four decades ofpoverty reduction in China: drivers, insights for the world,and the way ahead[M]. Washington: The World Bank, 2022.

[28] LIU L, CAO C J, SONG W. Bibliometric analysisin the field of rural revitalization: current status, progress,and prospects[J]. International Journal of EnvironmentalResearch and Public Health, 2023, 20(1): 823.

[29] SEMPREBON G. Rural futures: toward an urban(ized) peasantry in the Chinese countryside[M]. Siracusa:LetteraVentidue Edizioni, 2022.

[30] China Development Research Foundation. China’srural areas: building a moderately prosperous society[M].London: Routledge, 2017.

[31] XI J. Examine the “Three Rural Issues” from TwoPerspectives[M]//XI J. Zhejiang, China: a new vision fordevelopment. Hangzhou: Foreign Languages Press,2019:312-313.

[32] WEI H K, CUI K, WANG Y. Goal evolution andpromotion strategies of rural revitalization in the view ofcommon prosperity[J]. China Economist, 2022, 17(4): 63-76.

[33] WU Z X, WEN Y F. Analysis on the strategy of RuralRevitalization in China in the perspective of intellectualproperty right[J]. South Florida Journal of Development,2022, 3(1): 1176-1181.

[34] 新华社. 中共中央办公厅 国务院办公厅印发《乡村建设行动实施方案》: 中央有关文件. 中国政府网[EB/OL].(2022-05-23)[2024-04-10].https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2022-05/23/content_5691881.htm.

[35] 清华大学. 清华等19 所高校发起成立乡村建设高校联盟[EB/OL].(2021-12-22)[2024-04-10].https://www.tsinghua.edu.cn/info/1182/90242.htm.

[36] 人民网.“ 百校联百县兴千村” 行动启动: 社会· 法治[EB/OL]. 人民网.(2022-09-08)[2024-04-10].http://society.people.com.cn/n1/2022/0908/c1008-32521841.html.

[37] 央视网.“ 百校联百县兴千村” 行动启动仪式在山东举行: 乡村振兴[EB/OL].(2022-09-09)[2024-04-10].https://xczx.cctv.com/2022/09/09/ARTIf87roAkiOolcbPR44gau220909.shtml.

[38] 清华大学乡村振兴工作站.2024 暑假清华大学乡村振兴工作站考察实践派出申请说明及申请公告[EB/OL].(2024-03-16)[2024-04-13].http://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzkwMjQ5MTgxMQ==amp;mid=2247545205amp;idx=1amp;sn=baed52dedd2652e36d817fd488bce5d4amp;chksm=c0a6cab9f7d143af35b40519ac6397d9ca88181108317eb57161eae29aa11bdfd91fcf8fc612#rd.

[39] DESIGN D A, XU T, FEIREISS K, et al. DnA designand architecture: rural moves: the Songyang story[M].Berlin: Aedes, 2018.

[40] XU T. Architectural Acupuncture[M]//WANG J. TheSongyang story: Architectural Acupuntucture as Driver forProgress in Rural China: Projects by Xu Tiantian, DnA_Beijing. Zürich: Park Books, 2020.

ORIGINAL TEXTS IN ENGLISH

The Countryside ArchitectAn Analysis of Architects and AcademicInstitutions Involved in China’s RuralRevitalization

Lidia Preti

Introduction

“A rural revival is needed to counter urbanization across the globe.” [1]

Yansui Liu, Yuheng Li

As the world pursues urbanization andindustrialization, rural decline emerges as acontemporary global phenomenon[2]. In the frameworkof globalization and urbanization, the progression andenhancement of both rural and urban areas exhibita duality of both prosperity and controversies [3]. Ina country such as China, where rural land embodiesthe foundation of its civilization representing 92% ofthe available land - with approximately 8.8 millionsquare kilometers [4] - the scale of the countrysidetransformation cannot be overlooked.

Over the past three decades, the impacts ofurbanization processes and the consequent massmovement of populations from rural areas to urbancenters are also discernible by examining the urbanruralratio. Looking at the total population by urban andrural residence, the China Statistical Yearbook reportsthat in 2023 the rural population represents around 35%of the total population [5], which significantly decreasedcompared to the percentage in 2001, accounting for64%[6]. This is further reinforced if we look at theurbanization rate that from 1949 to 2012, increased from10.6% to 52.6%[7]. The processes of urbanization andthe construction of large-scale infrastructure in Chinaover the past decades have undoubtedly garneredglobal attention. Concurrently, albeit with far lessvisibility on the global stage, the Chinese governmenthas redefined its rural areas[8]. The opening up reformsand rapid urban development over the past 40 yearsdrastically changed the relationship between urbanand rural areas while, over the past two decades, ruralareas have changed from auxiliary roles and reserveforces to important components and main carriers inthe regional development in China. Consequently,over the last 20 years, reconsidering strategies for ruraldevelopment and rejuvenation appears to be a pressingglobal challenge that holds great relevance in theinternational discourse. The rural landscape has transitionedfrom facilitating urbanization and industrialization toencompassing comprehensive urban-rural planning andintegration initiatives [9] gaining renewed attention forthe sustainable development of rural areas.

In China, design and planning disciplineshave been recognized for their significant role inreshaping rural landscapes, particularly within thecontested rural-urban dichotomy, with a recentemphasis on rural revitalization practices. Presently,the Chinese countryside grapples with three primaryrural issues ( 三农问题, san nong wenti): issuesconcerning agriculture, rural areas, and farmers [10].These challenges have prompted a policy responseto promote harmonious development aiming for amultidisciplinary approach, fostering innovative methodologies to revitalize rural settlements. Insupport of this hypothesis, in recent years the nationhas introduced a series of national strategies, shiftingfocus from urban centers to the “invisible China”.

Thus far scholars from various disciplines havestudied rural revitalization from different angles,from the economic and political reasons behind therenewed attention toward the countryside over the lastyears to the policies, methods tools for implementingrural revitalization in different areas of the country.However, few articles and studies focused on thedirect correlation between rural revitalization,policy implementation, and the consequences onarchitectural practice in the Chinese countryside.The study aims therefore to offer a new perspectiveexamining the comprehensive impact of ruralrevitalization policies on architectural practices overthe past two decades, focusing on the engagement ofarchitects and academic institutions in this process. Todo so, an analysis is proposed within the frameworkof the “policy-phenomenon-effect” to examine thecomprehensive impact of the rural revitalizationpolicies in China. It is used as an approach to dissectthe intricate layers of policy impact, the resultant ruralrevitalization phenomenon, and the subsequent effectson architectural practices. Demonstrating considerableexpertise, Chinese architects have explored diversemethodologies, challenged conventional practices,and critically evaluated entrenched beliefs. Theirinitiatives encompass a range of approaches, fromutilizing local materials and traditional buildingtechniques to engaging in participatory designendeavors with local communities. Reconsideringstrategies for rural development constitutes a pressingglobal challenge that holds great relevance in theinternational attracting over the last decades theattention of the government, scholars, and academicinstitutions becoming a fertile ground for research 0.

1 O v e r v i e w o f C o n t emp o r a r y R u r a lRevitalization Practices in China

1.1 Introduction to Rural Revitalization in China

When talking about rural revitalization, the19th National Congress of the Communist Partyof China (CPC)1 represents a key moment for theapproach to the countryside being the concept of ruralrevitalization raised to the national strategic level forthe first time [11]. The convening of the 19th NationalCongress on October 18, 2017, marked a seminaljuncture in the trajectory of rural development withinChina. Implementing the rural revitalization strategyconstitutes a pivotal approach to maintaining theprioritized development of agriculture and ruralsectors, attaining the comprehensive objective ofmodernizing agriculture and rural domains, andformulating and refining the framework, mechanisms,and policy systems promoting integrated urban-ruraldevelopment [9]. Rural revitalization can be regardedas a second season of rural development shiftingfrom quantity to quality [12] and deemed essentialfor the nation’s overall rejuvenation. Following the19th National Congress, the Central Committeehas articulated a significant strategic initiativeemphasizing the prioritization of agricultural andrural development, with the overarching goal ofcomprehensively advancing rural revitalization. Thediminishing of the socio-economic divide betweenurban and rural locales and the rural-urban integrationthrough a multi-level goals system constitutes one ofthe first ways to realize China’s rural revitalizationstrategy [13]. Its essence lies in expediting themodernization of agriculture and rural developmentacross five core areas: “thriving businesses, pleasantliving environments, social etiquette and civility,effective governance, and prosperity” [14].

The attention of the Chinese governmenttowards rural areas, although notably amplified since2017, is by no means a recent phenomenon. Sincethe establishment of the People’s Republic of China,policies concerning rural areas have been consistentlyrefined to evolve together with the economy andsociety [15]. Under the banner of village modernization,numerous programs have been promoted since thebeginning of the 21st century2. The government’seconomic strategy during the 10th Five-Year Plan(spanning from 2001 to 2005) included the revision ofrural development policies as a central component[16].As the 10th Five-Year Plan period was coming to anend, following the policies for rural development,at the end of 2005 the building of a “New socialistcountryside” ( 建设社会主义新农, jiàn shè shèhuì zhǔ yì xīn nóng) was proposed at the nationallevel in October at the Fifth Plenary Session of theSixteen Central Committee of the Communist Partyof China[17]. Prior to the national resonance of thepolicy, Ganzhou ( 赣州) was the first prefectural cityin China to start in September 2004 a policy underthe guise of a new socialist countryside that is todayknown as the “Ganzhou model” [18]. The policy wasthen officially approved by the National People’sCongress in March 2006 [19].

“Comprehensive rural reform requires that wefocus on the new pattern of integrated development ofurban and rural areas to build systems and mechanismsthat encourage industry and cities to fuel the growthof agriculture and rural areas3 [20].” In alignmentwith this trajectory, between 2004 and 2005 theagricultural tax abolition was launched. In 2004 theChinese government announced the decrease of theagricultural tax by 1% to fully abolish it in 5 years[21].The agricultural tax that has played an important rolein the support of the industrialization of the countrysince 1949 [22] was officially removed by all provinceson January 1st, 2006. This represents a pivotal date inthe changing role of the countryside: from supportingand paying for the development of urbanizationand industrialization of urban areas to an importantcomponent of the overall national development.

1.2 2013-2021: Rural Revitalization as the coreFocus of Rural Policies

The rural revitalization policies represent thecontinuation of previous plans related to povertyalleviation [23], which can be seen as the prerequisite ofrural revitalization [24]. In 2013 the Chinese governmentput forward the goal of building a beautiful countryside( 美丽乡村建设,měilì xiāngcūn jiànshè) with the“No. 1 Document of the Party Central Committee”[17] focusing on the sustainable development of ruralareas. In the same year the government initiativeBeautiful Village was launched by the Ministry ofAgriculture choosing 1000 villages as pilot cases [25].The implementation of the initiative represented asignificant achievement that generated considerablepublic interest [26]. As mentioned in the introduction,the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party ofChina, together with the “National Strategy of RuralRevitalization” ( 乡村振兴, xiāngcūn zhènxīng)announced contextually, marks a turning point in theapproach to the Chinese countryside. Indeed, the term振兴 (zhènxīng, revitalization) began to dominatethe policies of those years and became central to thediscourse on the countryside. In the same year, theCentral Rural Work Conference (CRWC) was held inBeijing from December 28th to December 29th wherethe plan for the overall countryside regeneration waspresented outlining the road to rural revitalizationand mapping out plans for the upcoming year.In 2018, after the directions of the 19th NationalCongress, China released the “Strategic Planning forRevitalization of Rural Areas” issued by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC)and the State Council. The 100th anniversary of theCommunist Party of China in 2021 marked a keymoment to announce the achievement of the objectivesset in previous years such as the poverty alleviationthat saw a period of “final push” between 2017 and2021, and it was declared officially eradicated in2021, lifting over 770 million people out of povertysince 1978 [27]. In the same year was promulgated thelaw on the Promotion of Rural Revitalization4 ( 中华人民共和国乡村振兴促进法, zhōnghuá rénmíngònghéguó xiāngcūn zhènxīng cùjìn fǎ), enacted tofully implement the rural revitalization strategy, fosterthe comprehensive advancement of agriculture, ruralareas, and farmers, and expediting the modernizationof agricultural and rural sectors. Subsequently, in 2021the National Rural Revitalization Bureau was openedreplacing the State Council’s poverty alleviationoffice.

Looking at the academic studies on thecountryside, in the last decades the discourse hasbeen redirected toward the countryside with a stronginterest of the national and international academiccommunity in the study of rural areas and theirtransformation. This scholarly attention extends tothe burgeoning field of rural revitalization practices,which have experienced significant expansion inrecent years. A review of the existing literature onrural revitalization, covering the period from 1991 to2021, was published in 2023 by Liu Leng, CongjieCao, and Wei Song. The study revealed that duringthe analyzed timeframe, over 3000 scholars havecontributed to the field, with a concentration ofarticles between 2017 and 2021, which the authorsdefine as a high-yield period [28]. The current studiesno longer focus solely on the urban-rural dichotomyyet encompass a wider array of policies aimed atfostering the harmonious and sustainable developmentof rural areas. However, predominant research areasoften focus on topics such as land use policy andmanagement, geography, sustainable development,and management implementation. Indeed, therecan be observed a lack of scholarly attention givento the architectural repercussions of these policies.As the following paragraph seeks to elucidate, theinterconnection between rural revitalization strategiesand architectural practice is a significant study areadeserving of closer examination. As illustrated inthe accompanying drawings, the trend of architectsengaging in rural areas within the framework ofrevitalization practices seems to closely align withthe policy incrementation targeting rural development(Figure 1).

2 Architects and Institutions’ Involvement inRural Revitalization: Three Phases

2.1 Proposed Classification of Three Phases

The rural revitalization strategy implementedby the Chinese government represents the last setof policies dedicated to the development of thecountryside [29]. The China Development ResearchFoundation (CDRF5) proposes a subdivision of theefforts towards the countryside according to policyshifts in three phases: the “invigorating” policies ofthe 1980s, the “stabilizing” policies of the 1990s,and the “repay the countryside” policies since 2000,China’s rural [30]. Transitioning the analytical lens froma policy-driven chronological subdivision towards anarchitecture-driven framework, this study endeavorsto propose a periodization (Figure 2) that divergesslightly from the framework discussed by previousscholars, to position architectural practices as thefocal point of the proposed chronological scheme. Thestudy focuses on the analysis of the work carried outby architects and academic institutions in rural areasaiming to comprehend the context and policies thathave resulted in the transition between the differentperiods. Through a systematic study of the architectureproduction in the countryside within the framework ofrural revitalization strategies, the analysis unfolds inthree distinct periods (Figure 3): the pioneering phase(1978-2003), the maturing phase (2004-2021), and theconsolidating phase (towards 2049).

Pioneering Phase 1978—2003

Starting from the late 1980’s, the scholarlyattention toward the countryside was mainlyconcerning the heritage preservation of vernaculararchitecture. Under the guidance of Professor ChenZhi Hua, in 1993 was established in TsinghuaUniversity Rural Architecture Research Institute of theSchool of Architecture ( 建筑学院的乡土建筑研究所) and since its inception has been dedicated to thestudy of vernacular architecture in China. The grouphas extensively examined the history, culture, andlocal characteristics of rural architecture, continuingthe tradition of scholars like Liang Si Cheng andLin Hui Ying, who focused on the preservation oftraditional architecture. December 2023, marked the30th anniversary of its institution on the occasion ofwhich was held in Tsinghua University the conference“From Vernacular Heritage to Rural Vitalization”( 从乡土遗产到乡村振兴, cóng xiāngtǔ yíchǎndào xiāngcūn zhènxīng). As suggested by the title ofthe conference, over the last thirty years, the focustransitioned from the preservation of vernaculararchitecture, what the literature defines as heritageledregeneration, to its adaptation to the wave of newconstructions over the last two decades. This is centralalso to the understanding of how the architecturalfocus on rural areas has transitioned from primarilyaddressing heritage preservation to the adaptation ofexisting buildings to the construction of new ones.

Maturing Phase 2004—2021

The stage defined as the maturing phaseserves as the focal point of this study. It is proposedto commence in 2004 when the “New SocialistCountryside” program was initially introducedand conclude in 2021 coinciding with significantadvancements observed in the “Rural RevitalizationStrategy” and “Poverty Alleviation” policies on theoccasion of the 100th anniversary of the foundationof the Chinese Communist Party. This period couldbe defined as the “giving back” period: “By creatinga new socialist countryside, public resources thathave been invested predominantly in cities aredirected more at the countryside” [31]. Throughout thisperiod, a notable increase in architectural projects inrural areas is observed, characterized by two maintrajectories. The first trajectory, termed independentexperimentation, spans approximately from 2004to 2011/2013. Concurrently during this period,urban planners were engaged in developing primaryinfrastructure in rural areas. The second trajectory,referred to as policy-driven practice, encompassesthe period from 2013 to 2021. During this timeframe,it can be observed an architectural response topolicies enacted for rural areas revitalization, notablybeginning in 2013 with the “Beautiful VillageConstruction” policy and further evolving with the“Rural Revitalization Strategy” introduced in 2017.This marks the period when architects begin to engagesignificantly in rural projects, leading to a considerableincrease in such endeavors. The policy-driventrajectory has elicited two distinct types of responses:on one hand, the response of independent architecturalpractice, and on the other, the institutional academicresponse to this phenomenon.

Consolidating Phase Towards 2049

This phase hypothesizes a projection of policy trends and efforts towards rural revitalization overthe next two decades, considering 2049 as a potentialmilestone for achieving the objectives set by policiesestablished during this phase. The path to ruralrevitalization is set to be a gradual one, initiatingwith actions aimed at meeting intermediate goals,all the while maintaining a vision towards the longtermobjective set for 2050 which aligns with theoverarching goal to establish a modern socialistnation by that year [32]. 2049 will also mark the 100thanniversary of the founding of the People’s Republicof China (PRC) signifying a milestone for thecountry. Therefore, purportedly the efforts toward thecountryside will be further consolidated during thenext 20 years to reach by 2050 revitalization of ruralareas in an all-round way [33].

3 Architects and Institutions’ Involvement in Building the Countryside: 2004—2021,Maturing Phase

The work of architects remains one of the mosttangible outputs of rural construction, enriching oraltering the rural landscape [25]. At the foundation ofthe study of architecture production in rural areas,lies a systematic analysis conducted by the authoron architects who, over the past two decades, havebeen engaged in practicing in rural areas in China.The study was carried out by analyzing almost 300projects6 published on the gooood7 platform, usingthe keyword “rural reconstruction of China” andexamining the period from early 2000 to 2022.The selection of the platform for studying thephenomenon is deliberate: a preeminent website in thefield of architecture, renowned for its authority anddistribution in the field encompassing architecturalprojects at different scales. Following the initial studyof the policies that prioritized rural revitalizationin the past two decades described in the previousparagraphs, the author cross-referenced the dataobtained from the project study, recognizing acorrelation between architectural production in thecountryside and policy implementation. The graphicalrepresentation distinctly illustrates a sharp increasein rural projects (Figure 4, Figure 5) aligned withnational rural revitalization policies (Figure 6) startingfrom 2015 with a peak between 2018 and 2019.The peak reached during 2018 and 2019 is expectedfollowing the previous reasoning: a rapid increase ofarchitectural production in the countryside followingthe rural revitalization strategy announced in 2017.Additionally, the analysis was crucial in supporting theinitial hypothesis that, beginning in 2015, a significantportion of projects were primarily commissionedby local governments (Figure 7) thus validating thepolicy-driven trajectory of the past decade.

By analyzing the architectural production, itis possible to identify two main trajectories. Thefirst trajectory, termed by the author independentexperimentation, spans approximately from 2004 to2011-2013, witnessing a phase of experimentation byindependent architects who undertook single tasks inrural areas. Clear examples of this tendency are theearly projects in the countryside by Li Xiaodong (YuhuElementary School in 2003, the School Bridge inXiaoxi, Fujian province in 2009, the Liyuan Libraryin Jiaojiehe Village in 2011) and those by Rural UrbanFramework (Qinmo Village in 2006, Mulan PrimarySchool in Huaiji County in 2011, the Lingzidi Bridgein Shaanxi province in 2012, Tongjiang RecycledBrick School in 2012) to name a few. These projectsare almost all traceable to basic infrastructuretypologies for villages, such as bridges and schools.During the initial stage of this phase, and beforethe wave of architects working in the countryside,planners were involved in the establishment ofprimary infrastructures, road systems, and some publicfacilities in rural areas setting pilot projects whoseexample will later be extended at the national level. Arepresentative instance of this trend is the pilot projectin the urban sprawl of Beijing undertaken for theShuiyi district, realized by the group led by ProfessorZhang Yue8 and Feng Ni9 awarded the Holcim AwardsGold 2008 Asia Pacific for Sustainable Planning fora rural community and Holcim Awards Bronze 2009Global the following year10. The second trajectory,referred to as policy-driven practice, encompassesthe period from 2013 to 2021. During this timeframe,there emerges an architectural response to policiesenacted for rural areas revitalization. This marks theperiod when architects begin to engage significantlyin rural projects, leading to a considerable increasein such endeavors. The policy-driven trajectoryhas elicited two distinct types of responses: on onehand, the response of independent architecturalpractice as demonstrated by the increasing numberof governmental clients, and on the other, theinstitutional academic response to this phenomenon.

Accompanying the line of national policydevelopment, the academic response to the policyimplementation for the revitalization of thecountryside is a noteworthy phenomenon. Indeed,since 2017 a progressive engagement of universitiesin rural revitalization practices was witnessed. Pioneerin this practice is Tsinghua University which, inOctober 2017, responding to the call of the NationalCongress concluded shortly prior, set the RuralRevitalization Center, as a model of cooperationwith local government to build workstations indifferent provinces of the country. On February 23rd,2021 the General Office of the Central Committeeof the Communist Party of China and the GeneralOffice of the State Council issued the “Opinions onAccelerating the Revitalization of Rural Talents”( 关于加快推进乡村人才振兴的意见, guānyújiākuài tuījìn xiāngcūn réncái zhènxīng de yìjiàn)followed in 2022 by the “Implementation Plan forRural Construction Action” ( 乡村建设行动实施方案, Xiāngcūn jiànshè xíngdòng shíshī fāng’àn)considering rural construction as an important task inthe implementation of the rural revitalization strategyand an important part of national modernization[34]. In December 2021, initiated by TsinghuaUniversity, 19 universities established the “RuralConstruction University Alliance” ( 乡村建设高校联盟, Xiāngcūn jiànshè gāoxiào liánméng) as acooperative mechanism established by universities tojointly help rural construction and develop and serverural modernization and to attract more universities toparticipate in rural construction [35]. Since its inception,104 universities have joined the Rural ConstructionUniversity Alliance. Following the aforementionedactions, on September 7th, 2022 the initiative “100schools, 100 counties, 1000 villages” ( 百校联百县兴千, bǎi xiào lián bǎi xiàn xīng qiān cūn) promotedby the National Rural Revitalization Bureau, togetherwith Tsinghua University was announced [36-37]encouraging universities to actively participate in ruralconstruction and countryside rejuvenation.

Following an initial comprehensive overviewof the various architects and institutions involvedin this process, the study focuses on three relevantrepresentatives of these trajectories. Li Xiaodong’spractice stands out as a pioneering force in rural projects,embodying the earliest independent experimentations inrural areas during the past two decades. For the policydriventrajectory, the Rural Revitalization Center ofTsinghua University has been selected as the mostrepresentative example of institutional response to thepolicies implementation while the practice of DnA_Design and Architecture studio is selected as anexemplar case of independent practice.

3.1 Independent Experimentation: Li Xiaodong’sPractice

A pioneer in self-initiated projects in theChinese countryside is undoubtedly Li Xiaodong. LiXiaodong (1963, Beijing) graduated from the Schoolof Architecture at Tsinghua University in 1984 andobtained his PhD from the School of Architecture,Delft University of Technology between 1989 and1993. His practice is primarily focused on smallscaleprojects with a strong holistic approach tothe site by integrating contemporary architectureand regional culture. When Li Xiaodong started topractice in the countryside (early 2000), the Chinesearchitectural scene was mainly dominated by largescaleurban projects designed and built by developers.Compared to the high constraints of the buildingindustry in the cities, projects in rural areas hadfewer limitations, allowing independent architectsthe opportunity to experiment with their practice onsmall-scale projects. The first project completed bythe architect, symbolically marking the beginning ofrenewed attention towards rural areas by architects,is the Yuhu Elementary School Expansion Project11in Lijiang, Yunnan province. The project is located inthe Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau at an altitude of almost2 800 meters asl in Yuhu village in Lijiang, an arealisted under the protection of the World CulturalHeritage Program since December 199712. At thattime, the primary school of the village, which hadbeen established just one year prior (2001), wasunable to meet the educational requirements andneeded to be expanded. Li Xiaodong’s practice in thecountryside continued until 2011 when he oriented hispractice towards urban areas. In 2009 the design ofthe Bridge School in Xiaoshi Village, Fujian Province,represents a breakthrough not only in terms of designbut also in terms of typology: it embodies the firstbuilding combining both the typology of the schooland the bridge in one building. 28 meters long and 8.5meters wide, the building overcomes the traditionaltypologies connecting two sides of a creek and theTulous existing on the site. The last project realizedby Li Xiaodong in the countryside before his practicemoved to urban areas is the Liyuan Library. Locatedin Jiaojiehe Village within the Huairou District ofBeijing, the project was built in 2011 and is the firstlibrary built in the countryside, later on followed bymany projects following this typology. The practice ofLi Xiaodong in the countryside obtained internationalrecognition winning numerous awards.

3.2 Policy-driven Practice

3.2.1 Institutional Response: Tsinghua University and the Rural Revitalization Center

Looking at the academic panorama, TsinghuaUniversity is undoubtedly a pioneer in the engagementof academic institutions in rural revitalizationpractices. In October 2017, accompanying the line ofnational policy development, and responding to thecall of the “Rural Revitalization Strategy” announcedduring the 19th party congress, Tsinghua Universityfounded the Rural Revitalization Center ( 清华大学乡村振兴工作站, qīnghuá dàxué xiāngcūn zhènxīnggōngzuò zhàn). Originally initiated by the Schoolof Architecture, over the past seven years the centerhas conducted projects collaboratively by multipledepartments, under the guidance of the school PartyCommittee and with the support of the CommunistParty Committee of Tsinghua University together withthe Youth League Committee. Over the past years, theCenter has organized more than 460 teams comprisingover 7,000 faculty members and students frommore than 200 colleges and universities across over100 disciplines[38]. The Rural Revitalization Centerof Tsinghua University introduced an innovativeapproach to countryside revitalization by establishingpermanent workstations in rural villages. Theseworkstations function as a dual-purpose platform:they serve as a physical base for students conductingactivities in rural areas during winter and summerbreaks and. when not in use by students, they oftenfunction as community centers or support facilitiesfor villagers. Each break, students from variousdepartments and affiliated universities have theopportunity to spend time in these villages, sharingtheir knowledge and expertise across different fields.

3.2.2 Independent Practice Response: DnA_Designand Architecture Studio

DnA_Design and Architecture studio, aBeijing-based design office founded in 2004 by XuTiantian, is undeniably one of the most influentialand internationally renowned offices working oncountryside revitalization in contemporary China.Differing from the architectural landscape of majorChinese cities, characterized by a tendency towardsbuilding standardization due to rapid urbanization, theapproach of the DnA office redirects attention to theutilization of locally sourced materials, resources, andexpertise. This involves the incorporation of traditionalartisanal construction methods often marginalized bythe rapid development typical of urban centers. Lookingat the architectural production of the office from 2015to 2023, it is noticeable how most of the projects areconcentrated in Songyang County, in the southwestof Zhejiang province under the administration ofLishui City. Defined as “The Last Hidden Land inJiangnan” ( 最后的江南秘境, Cóng xiāngtǔ yíchǎndào xiāngcūn zhènxīng), Songyang has fully preserved70 traditional villages exploring the rural revival led bycultural interest [39]. With around 20 projects realizedin the area, through small interventions, Xu Tiantianbrought rural redevelopment beyond the design ofsingle architectural objects developing a multiscalegrowth in the area. The approach is clear: architectureacupuncture as a sustainable rural strategy. Bydesigning with minimal intervention public programsare introduced to the villages, each of them respectingthe cultural heritage and context [40]. Upon examiningthe clientele behind the various projects in theregion, it becomes evident that these initiatives arepredominantly commissioned by local governments(Songyang Dadongba County Government, SongyangPublic Road Administration, People’s Governmentof Zhangxi Village, Songyang County, VillageCommittee of Wang Village, People’s Governmentof Dadong Ba Town, Songyang County, etc.). Thisobservation supports the initial hypothesis, suggestinga correlation between the increase in projectsundertaken in rural areas and the revitalizationpolicies enacted for the countryside.

In conclusion, rural revitalization practices playa pivotal role in contemporary China encompassingthe architectural discourse of both academicinstitutions and independent practice. The recentstudies mainly focusing on the policy framework,often overlook the effects of these transformationson the built environment. This study highlightsthe role of architects and academic institutions inthe Chinese countryside over the last two decades,aiming to enrich the ongoing discourse on ruralrevitalization while proposing a periodization focusedon architectural practices. The proposed chronologicalbreakdown into the pioneering phase, maturingphase, and consolidating phase allows for a nuancedunderstanding of the evolution and impact of thesepractices. By examining cases such as Li Xiaodong,the Tsinghua University Rural RevitalizationCenter, and the practice of the DnA_Design andArchitecture office, the study substantiates the diverseyet converging paths through which architecturecontributes to rural revitalization.