腹地科学的研究倡导

摘 要 本文倡导建立一种腹地科学,将城市中心与乡村景观之间的过渡区域视为充满活力且复杂的区域,值得建筑与城市规划学科给予特别关注。作者从“hinterland”的中文译名“腹地”中汲取灵感,提出了腹地概念的定义,以表达这种中间区域的多面性特征。该定义构成了分形理论的基础,始终能够在不同尺度上应用,大到全球视角,小到单个建筑的定义。本文对城乡分类进行了文献综述和历史回顾,包含弗兰科潘(Frankopan)等历史学家的见解,多希阿迪斯(Doxiadis)的人类住区与生态学理论、吴良镛的人居环境科学导论,以及库哈斯(Koolhaas)对乡村的最新观察等。本文通过方案研究和案例应用,进一步展示了腹地地区所面临的独特挑战及其可能的应对策略,强调了传统城市策略的不足。另外,文章通过描述腹地的需求和特征,旨在为全面的腹地科学提供道路,以解决当代城市化的复杂问题。本文旨在简要概述这一新理论的定义、需求和可能的特性,并举例说明其实际应用情况,目的是提出一种策略,该策略试图为一个在学科中经常被忽视的领域建立一个定义,无论是在物理层面还是在思维层面。

关键词:腹地;科学;新理论;国家战略腹地

1 什么是腹地?

在实践和学术研究过程中,笔者意识到在建筑和城市规划的论述中,城市与乡村之间存在明显的对立,这往往使非城市地区被边缘化。在笔者就读于代尔夫特理工大学(TU Delft)时,城市密度和城市发展被视为最终的目标,这种理念在库哈斯(Koolhaas)的《疯狂的纽约》(Delirious New York) 中得以表现和赞美,以及他工作室在大都市建筑上的成功,并且MVRDV 的《KM3:密度探险》等书籍中也是如此[1]。尽管在过去的20 年中,一些建筑师也观察到一种渐变的范式,例如在《乡村:一份报告》(Countryside: A report)中[2],开始更多地关注“城市”的对立面。然而仔细观察,可发现这种对立似乎仍然存在。在笔者看来,这种范式的转变仍然不足,且不完整。笔者来自荷兰,一个典型的在全球定义中城市和乡村之间缺乏明显边界的国家,并且广泛探索了中国和其他各种地区,笔者观察到一种介于两者之间的领域,打破了这种严格的对立,即大量人口居住在主要城市区域之外,但并非严格的传统乡村环境。在中国,仅这种地区就占约30% 的人口和较大比例的GDP。除了“大都会建筑事务所(OMA)”,人们还有各种“乡村实践”,但目前为止,似乎还没有“事务所”或“理论”专门针对这类“中间区域”。

这一腹地科学的研究计划源于对建筑和城市规划学科中一个关键但常被忽视的领域的认识,即存在于城市中心和乡村景观之间的过渡空间。随着城市化进程持续重塑人们的生活环境,对这一专业理论的需求日益增长,该理论能够描述这些中间区域的复杂性。这也符合理论定义和社会文化领域日益增长的趋势,即为追求 “更多城市化 ”提供另一种选择。无论是如“泡沫经济”中那样[3],反对城市持续增长的追求,还是像中国的乡村振兴实践那样,关注中国欠发达乡村的发展,都对“超越城市”的问题有越来越多的关注,旨在以广泛的视角将人类发展和周围环境联系起来。本文旨在为建筑和城市设计学科中的这一具有可替代性的综合理论奠定基础,从“hinterland”的中文译名 “腹地”中得到启发,提出基于分形理论的概念,可在不同尺度上广泛应用,从而便于对之前被忽视的腹地的整体理解。

1.1 定义

关于“腹地”的定义,最初是一个德语词,字面翻译成英语为“the land behind”。地理学家乔治·奇泽姆(George Chisholm)在其《商业地理手册》中首次记载了该词的用法[4]。在英语中,美式和英式的定义略有不同。依据本文的目的,采用美式定义,将其描述为“一个位于可见或已知范围之外的区域”,并附加了“基础设施欠发达的人口稀少区域”的定义。翻译成中文为“腹地”,字面意思是“位于中间地带的土地”。因此,它描述了一种“隐藏且重要”的土地,就像身体的器官(腹部)一样,有几个特征,其中最重要的是人们无法离开它而生存。例如,与缺失肢体相比,人类无法在缺失心脏、大脑或腹部的情况下生存。此外,在中医理论中,腹部具有恢复功能。人体,以及类似的一个地区或国家,被认为利用“腹”来储存能量,并从腹部进行(物理上的)恢复。

在这个倡导中,本文将腹地定义为“后方的土地”,即通常被忽视的、超出人们主要关注和兴趣范围外的土地,并承认腹地作为更大系统中的一个重要器官的特征。

1.2 建筑和城市设计背景下的腹地

将“腹地”应用于建筑、城市设计和规划学科,需要对城市和乡村的定义,以及这些领域的关键理论进行背景探索,旨在建立一个细致入微的框架,以应对中部空间的独特特征和挑战。该框架将作为描述“腹地科学的理论与实践”的基本条件。

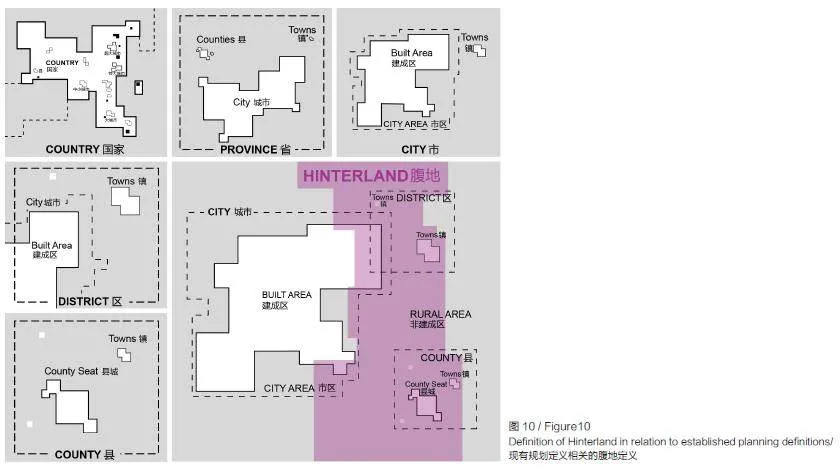

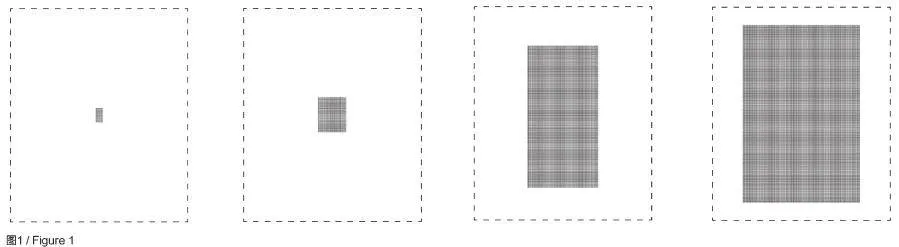

首先,必须承认的是,对城乡分类的研究缺乏全球公认的定义,这阻碍了国际比较,并且凸显了建立一个更准确框架的必要性。例如,目前联合国报告的数据是基于各国定义的城市化比例。问题在于,各国对城市化的定义显著不同。不仅城乡的划分标准不同,而且使用的衡量标准也不同。一些国家使用最低人口数量作为衡量标准,而另一些国家则使用人口密度、基础设施发展、就业类型或简单使用预定义的城市人口作为衡量标准。这意味着,丹麦认为一个定居点有200 名居民即为城市[5],这与中国大不相同,中国认为一个地区有超过2 万名居民即为城市[6],而日本认为一个城市至少需要5 万人[5]。如果将中国的定义用于丹麦,那么丹麦可能只有极少数地区可以称为“城市”;反之,将丹麦的定义用于中国,几乎所有的地区都可以称为“城市”(图1)。近期的一些高级别欧洲政策研究,试图通过强调定义的差距来思考这些问题,并旨在为未来发展提供一个学术性、跨学科和以设计为基础的框架。2020 年,在欧洲委员会(EC)区域和城市政策总局协调下,6 家国际组织:欧盟(EU)、联合国粮食及农业组织(FAO)、国际劳工局(ILO)、经济合作与发展组织(OECD)、联合国人类住区规划署(UN-Habitat)和世界银行,联合多名学者,关于国际统计比较中城市、城乡区域的划分方法提出了建议[7],本文的提议基于其中一些建议。欧洲委员会提出了一种新的方法,称为城市化程度,将一个国家的整个领土分为3 类:①城市;②城镇和半密集区;③农村地区。在本文提议中,将第2 类地区即中间区域,称为“腹地”。这与欧洲委员会提出的观点基本吻合,但又更进一步,承认其为一个特定的领域。腹地框架解决了全球缺乏城市和农村地区通用定义的问题,为国际比较和规划提供了一个有价值的工具,而无需对城市、农村分类进行严格的通用定义。事实上,腹地框架旨在打破传统的农村与城市之间的二元对立立场。当代城市化不断发展的演变动态及其与周边生态环境的关系,要求人们对繁华的城市中心与宁静的乡村景观之间的过渡区域有一个更细致的理解。对“腹地”的重新定义,体现了这些中部空间的多面性。这种概念转变促进了一种更具包容性和整体性的建筑与城市规划方法,有助于人们理解在塑造环境的过程中,城乡元素之间的复杂作用。

其次,尽管腹地科学本身是一个新的理论框架,在建筑和城市设计领域,现有理论源自对当代发展的同类观察,可以为在建筑和城市设计背景下,框定腹地的发展潜力提供良好的基础。例如,多希阿迪斯在1968 年提出的人居学和人类居住环境理论[8],提供了人类住区与其环境相互作用的宝贵视角。吴良镛的著作《人居环境科学导论》提供了进一步的见解[9],全面阐述了人居发展的内在复杂性。这些成熟的理论为腹地的概念化奠定了基础,不仅将其视为地理空间,更视为城乡元素交汇的动态过渡领域。将这些理论基础与实证研究相结合,对形成当代城市化的综合性和适应性方法至关重要。此外,有证据表明,某些腹地正在振兴。例如,冯描述了中国乡村如何通过市场、图书馆和酒店得以振兴[10],其他重要的观察包括德尔加多·维纳斯(DelgadoVinas)对城乡互动的探索[11],卢对中国城市化战略的评估[12],卡森对城乡发展脱节的研究[13],以及约翰·韦尔什(John Welsh)的批判理论[14]。这些研究显示出腹地动态变化的性质及其创新和再生的潜力。

最后,腹地的战略重要性在近期的政策讨论中得到了认可。2023 年12 月,中国中央经济工作会议上提出了“建设国家战略腹地”的概念。根据蒲和马在2024 年的说法,这一概念旨在通过划定腹地的关键地理属性和战略特征,优化生产力布局,并保障国家安全[15]。国家战略腹地具有一些基本特征,如关键的地理位置、强大的经济韧性及其对创新和发展引擎的作用。腹地促进了城市文化的凝聚,代表了经济发展的新增长极和动力源。要将战略决策转化为实际成果,系统推进国家战略腹地的建设是必不可少的,包括加强高层战略规划,协调建立战略物资储备,支持战略科技能力建设,以及发展战略运输能力网络。通过这些做法,腹地就能在新时代持续推动经济高质量发展和先进的安全基础设施建设。

通过在建筑和城市设计的背景下重新定义腹地,人们认识到腹地在塑造可持续和有韧性的居住区方面的独特作用和潜力。这个框架为理解和解决中部空间的复杂性提供了一个全面的方法,促进了城乡规划中的创新性和适应性。

1.3 被忽视的领域

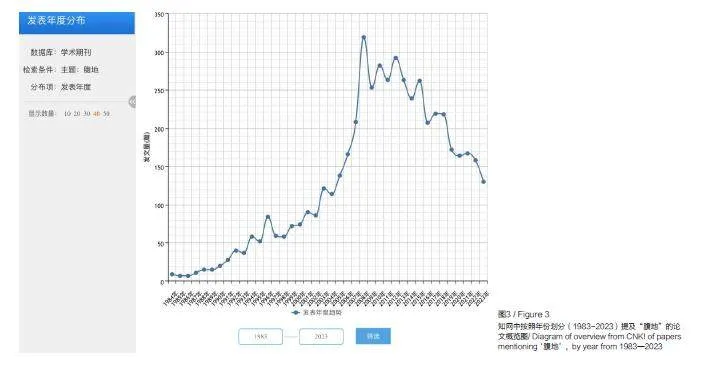

以 CNKI 中国知网数据库为参考,分析对“腹地 ”的现有研究可以发现,在经济学、基础设施、农业、政治学等学科中,这一领域的研究非常广泛,出版物稳步增长,在 2008 年前后迅速上升,并达到顶峰。在此之后,对这一领域的研究持续得到关注,特别是由于2023 年中央经济工作会议的相关发言,未来几年内对腹地的研究数量预计会有所增加(图2)。然而,尽管这一领域在总体上和政治上都引起了广泛的关注,但在建筑科学、建筑工程、建筑与规划等领域却依然被忽视,对腹地的研究占该领域论文总数的比例不足1.5%(图3)。建筑学科可能被期待在这一领域的研究和发展中扮演重要角色,因为其具有塑造建筑环境、连接人类与居住环境的能力。但事实并非如此,建筑师库哈斯在其2020 年出版的《乡村:一份报告》(Countryside: A report)中指出了这一不足,并将腹地描述为“被忽视的领域”[2]。库哈斯描述了人类历史上各国政治领袖和社会如何关注腹地,而在当代(受西方影响下)城市社会中,这一关注已被遗忘和忽视[2]。

库哈斯将他的注意力从繁荣的城市生活转移到这些非城市地区隐秘的过渡空间上,挑战传统观念,并认识到过渡空间重要性。库哈斯强调,城市生活方式在前所未有的规模上深刻影响了非城市地区(库哈斯所称的“乡村”)的组织、抽象和自动化。这种转变引发了由雄心、愿景和政治意志驱动的重大政治和社会重组。以他在书中提出的全球乡村为背景,该领域不仅仅是城市中心的被动背景,而是一个由复杂力量塑造的动态化领域。库哈斯的工作揭示了这一领域是试验研究的前沿,各国和各种背景下的新社会结构和创新实践在这里涌现。本文提出的腹地概念框架与库哈斯定义的“被忽视的领域”不谋而合,事实上,这可能是一个更为恰当的定义,因为“乡村”具有与农村生活相关的特定含义。相反,腹地代表充满潜力和转型的空间,对传统的乡村生活概念提出了挑战。“被忽视的领域”对“腹地”的多层次定义,进一步确认了这一被忽视领域的潜力和重要性。因此,通过记录和分析这一领域正在发生的变化,库哈斯对腹地不断变化的状态提出了重要见解。他的观察表明,腹地并非静态,而是在新的社会组织形式和技术进步的推动下,正在发生重大变化的动态区域。

库哈斯的作品是城市以外生活的重要记录,为这些地区正在进行的转变进程提供了宝贵的证据。他的研究对于人们理解全球腹地状况具有重要意义,为评估和创新这些常被忽视且充满活力的景观提供了基础。实际上,库哈斯邀请人们重新审视对这一被忽视领域的早期观念。他强调其变革、适应和创新的能力,提示建筑师、城市规划者和政策制定者将腹地视为一个充满潜力和无限可能的领域,而非一成不变的农村区域。这种观点对于在可持续发展和城乡动态的背景下应对腹地带来的挑战和机遇至关重要。库哈斯的见解突破了人们对腹地的认识和参与方式,倡导以更加细致入微、更具前瞻性的方式来研究和发展腹地。他的研究不仅强调了对这一非城市领域进行定义的需求,还展示了当前讨论中尚未覆盖的该领域的广泛主题。

1.4 腹地的历史背景

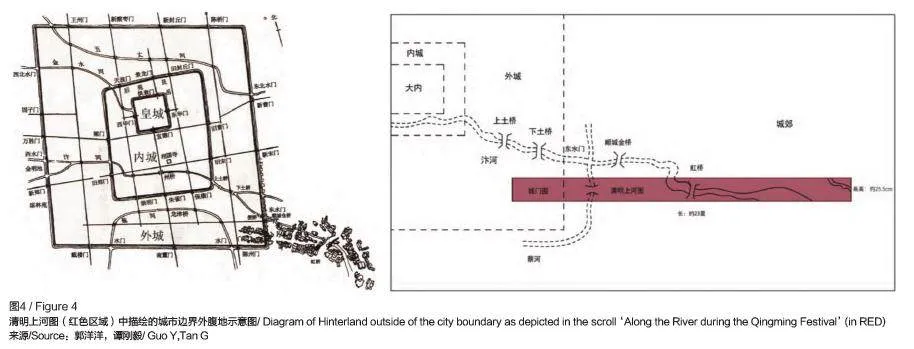

如今,人们常常认为城市化是典型的现代现象。然而,事实并非如此。为了更好地理解“城市——非城市”关系在过去几千年中的变化,以及这如何导致了非城市地区成为一个相对“被忽视的领域”,并通常带有负面含义,人们需要探讨这种动态的历史演变。牛津大学全球史教授弗兰科潘(Frankopan)在《地球的转变》一书中描述了“财富差距成为最早和最密集城市化人口的特征”,这一现象创造了将城市视为寄生体的模式,在这种模式中,城市增长的动力来自劳动力,而收益则被精英阶级攫取,并设立壁垒,以巩固自身地位,并同时限制他人的进入[16]。弗兰科潘描述了城市、乡村和腹地之间的关系在历史上经历了显著的转变,这些转变受经济、社会和环境动态的影响[16]。例如,在古代中国,他描述了秦朝期间,当权者如何努力将劳动力与土地捆绑在一起,以确保高农业生产。这是通过维持户籍来防止农民流动,从而有效地将农民绑定在他们的农业角色上(图4)。这种方法强调了历史上对农业劳动力的依赖,以支持城市中心和国家更广泛的经济稳定。古希腊和古罗马的哲学视角进一步说明了城乡对立。苏格拉底在柏拉图的记述中说道:“从树木、自然和乡村中学不到什么;唯一能获得知识的地方是城市,从其他人那里。”苏格拉底否定了乡村作为知识来源的重要性,强调城市是唯一的知识增长之地。相比之下,西塞罗将农业浪漫化,将其视为一种理想的追求,但他忽视了那些以务农为生的人所面临的严酷现实。这种对农村生活的理想化,往往掩盖了农业工人所遭受的剥削和艰苦的劳动。

在历史上,城乡区域不仅通过劳动和经济依赖相互联系,而且通过环境重构紧密相连。动植物和农业技术在各地区之间的传播是由人类的需求和愿望驱动的,这种传播重塑了环境,以适应城市和农村的需求。例如,中国在汉朝期间,当权者引入土地开垦技术和新工具来提高农业生产力,这与世界其他地区(如罗马)发展相似。城市化在历史上也带来了严重的生态和健康挑战。老普林尼哀叹人类为了自我富裕而过度开发自然资源,警告人们环境将以自然灾害的形式对人类进行报复。全球的城市地区,因人口密度和不卫生的条件,成为病菌滋生地,使城市生活的健康和可持续性变得更加复杂。历史叙述还强调了不同地区在应对环境和社会政治压力方面的复原力和适应能力。在欧洲部分地区,农业实践的创新和向牧业的转变,帮助人们适应气候的变化和抵抗外部的威胁,如野蛮人的入侵。这些适应性措施促进了地方的自给自足,为应对食物短缺和城市的脆弱性提供了缓冲。阿拉伯学者借鉴希腊思想,研究环境条件如何影响人类特征和社会发展。这些观点强调了气候不仅塑造了人们的身体特征,还塑造了其文化和智力特征,反映了学者们对环境与人类社会之间相互联系的广泛理解。

总体而言,城市、乡村和腹地之间关系的历史演变,揭示了经济开发、哲学理论、环境管理和适应性复原之间复杂的相互作用。这些历史见解对于理解在建筑和城市规划中定义和驾驭腹地的当代挑战和机遇至关重要。研究被广泛认为是最重要的中国画作《清明上河图》,可以直观地体现这种视角的变化,及其与建筑和城市规划定义的关系。图4 展示了《清明上河图》中重点内容的平面图,强调了城市与乡村之间的“中间地带”,即腹地。这幅画的不同版本跨越了数百年的历史,进一步展示了城市、农村区域,及其对中间地带定义的演变。

1.5 分形理论

在构建腹地定义的基础上,作者发现该对概念的应用不仅限于“非城市”领域。本文旨在将这一原则作为一种分形理论加以介绍,并适用于各种尺度。腹地作为“腹部”区域,代表了人们所关注和隐藏在视线之外的,但对系统整体运行至关重要的部分之间的关系,这一现象可以在各种尺度上观察到。这不仅适用于腹地的字面“土地”定义,还适用于全球区域、国家、城市、校园,甚至建筑尺度。新的腹地关系和结构正在形成,这将引起人们对各种尺度“腹地”的关注,例如,大尺度(国际、国家、区域等)和小尺度(社区、校园、服务机构等)见图5。

在全球层面,腹地被定义为主要城市中心与偏远农村地区之间的过渡区域。这一定义延伸至区域和地方尺度,则涵盖了城市边缘区和其他中间区域。分形理论进一步渗透至微观尺度,影响腹地内个体建筑的设计和定义。甚至在建筑层面,这一概念也可以描述为类似于路易斯·康(Louis Kahn)定义的“服务与被服务空间”[17]。通过采用分形理论的方法,腹地科学承认了这一原则在不同尺度上的相互关联性,从而促进了学者们对过渡区、隐藏区域和被忽视区域的全面性和适应性理解,这些区域对于整体功能至关重要。本文重点关注城市、区域及其周边地区的中间尺度,以解释腹地这一概念的核心原则。

2 它为什么重要?

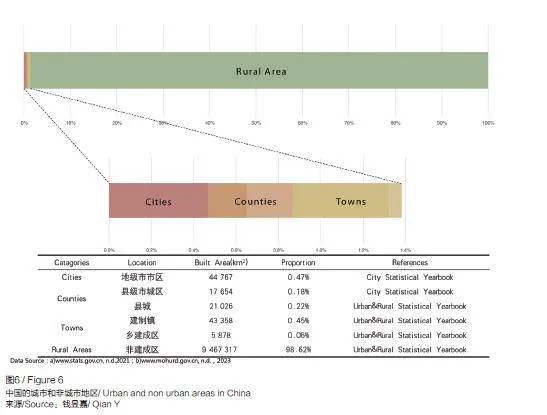

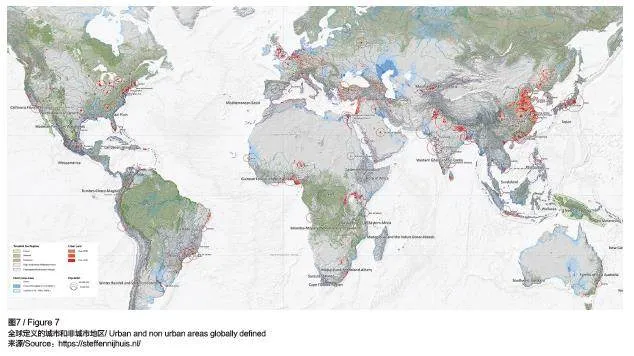

根据联合国《世界城市化前景:2018 年修订版》(World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018Revision),世界人口在2007 年首次出现城市人口超过农村人口的现象[5]。如今,全球超过一半的人口居住在城市,而这些城市仅占全球土地面积的2%。现有学科中大部分研究和实践都集中在这2% 的土地上。然而,剩余的98%的世界领土正是本文所提出理论的重点。这98% 的土地包括广袤的乡村地区、重要基础设施、工业、县城和未被城市化影响的野生景观(见图6 和图7)。代尔夫特理工大学教授斯特芬·尼豪斯(Steffen Nijhuis)在其就职演讲中展示的图像(图7)生动地说明了这一对比[18]。腹地作为城市中心和乡村广袤地带之间的动态领域,提供了独特的挑战和机遇。

如前文所述,历史上城市与农村之间一直存在着显著的分界。许多社会优先发展城市,视城市为社会中更高级、更文明的象征,而乡村则往往被忽视。根据弗兰科潘的观点,这种分化甚至是导致等级社会形成的最重要原因[16]。至今,城市化率仍被视为某一国家或地区发展程度的衡量标准,联合国指出,一个国家的财富与其城市化率之间存在相关性。然而,这种对城市化及其所谓积极方面的单一视角已经受到质疑。曾为城市化的强烈倡导者的库哈斯在2020 年指出,今天城市与非城市之间并没有真正的、相互的关系[2]。事实上,长期以来人们对城市化、城市和城市生活方式重要性的关注,导致了一些不必要和不理想的影响,这突显了建立特定框架以应对这些问题的重要性。当前的问题包括但不限于以下几类。

2.1 腹地的挑战

2.1.1 城市居民与非城市居民的分化

这种分化现象表现在人们对社会文化、资源分配和农村地区的普遍不满中。这种不满也体现在民主主义政党的兴起,以及阴谋论的传播,这种阴谋论基于人们担心欧洲或美国等西方国家被“遗忘”或“被城市精英控制”。这种分化加剧了社会分裂,阻碍了国家的综合发展。

2.1.2 非可持续的城市化

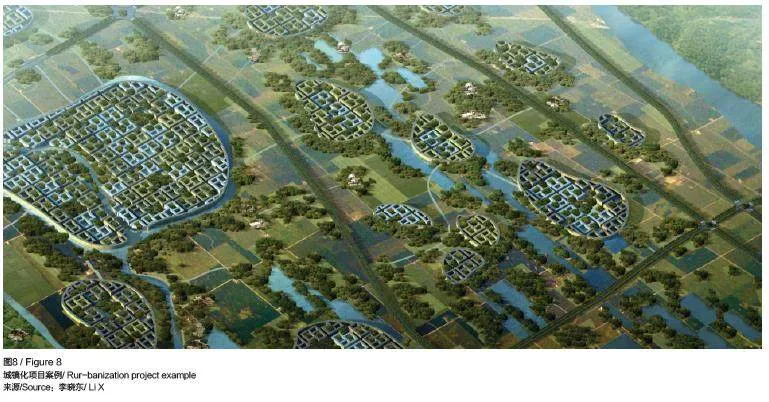

全面城市化引发了关于可持续发展和生活质量的问题。虽然高密度城市区域的平均财富可能较高,但它们往往面临过度拥挤、污染和疾病易发等问题。此外,城市基础设施的压力可能导致生活条件恶化、持续高水平的压力和抑郁症发病率增加,以及生育率急剧下降。因此,必须考虑全面城市化是否应该是最终目标,哪些替代模式可以更好地平衡人类进步与生活质量,从而造福整个社会。李晓东提出的“城镇化”概念为这一问题提供了一个有趣的尝试(图8),即一种适用于腹地地区的具体发展模式,其最终目标并不是使原来的农村地区完全城市化。

2.1.3 环境退化

对城市发展的高度关注,往往导致对农村地区和自然环境的忽视、剥削和退化。这可能导致森林被砍伐、生物多样性丧失和土壤退化。腹地地区有时仅作为支持城市增长的资源基地,而未采取足够的措施来维持其生态系统。城市地区及其居民自身在很大程度上免受这种环境退化的直接影响。2020 年2 月,库哈斯在接受《中国日报》采访时准确指出,环境退化和随之而来的气候变化在腹地地区更为明显。他说:“如果你在城市中,几乎感觉不到全球变暖。但一旦你走出城市,就会意识到天气变得奇怪,或者预期上出现了异常。[19]”最近的全球研究表明,超过70% 的农民已经看到了气候变化对其农场的重大影响[20]。在中国最大的农业省份——河南省,70.3% 的农民(约5,100 万人)认为气候变化对他们的生计构成了威胁[21]。

2.1.4 经济差距

对城市经济的关注可能加剧城乡之间的差距。农村地区可能会面临投资不足,导致经济发展机会有限和贫困率较高。这种经济不平衡问题可能加剧人口向城市的迁移,进一步加重城市基础设施的负担,导致农村人口减少,并加剧上述问题的严重性。这种差距还体现在服务和基础设施的可获得性方面,腹地地区通常难以获得医疗保健、教育和交通设施等方面的服务。这些差距可能导致生活质量下降,阻碍农村发展的潜力和其融入更广泛国家发展进程的可能性。

2.1.5 文化侵蚀

98% 的非城市地区往往拥有丰富的文化遗产和传统。对城市化的强调可能导致这些文化识别性受到侵蚀,因为年轻一代为了寻求更好的发展机会而迁往城市,这可能会影响通常在这一较大的非城市腹地发现的文化多样性。移民的涌入可能导致几个世纪以来一直保持的独特文化习俗和社区结构的消失,现在,这些文化遗产和传统都融入了统一的城市化熔炉,失去了其独特的传承。

2.1.6 城市自信

将城市原则应用于非城市环境确实存在危险。并非所有地方都是城市;并非所有地方都需要成为城市;并非每个城镇都需要一个博物馆;并非每个村庄都需要一个高铁站和高层办公楼;并非每个空旷的水域都必须建造一个数据中心。规划师、建筑师和政府工作人员试图利用和实施城市战略来发展或解决非城市地区的问题。相反,人们需要根据准确的情况了解和分析非城市地区存在的问题,结合当地的需求、习俗和要求,制定具体的实施策略。令人震惊的是,就中国而言,大部分重要的建筑物、资源、大学,以及建筑师都集中在一线城市(特大城市、超大城市和大城市),而这些城市仅占据总行政单位的不到5%(图9)。而成千上万的其他行政实体却受到较少的关注,但它们通常是以排名靠前的“成功”城市为模型构建而成。尽管行政定义并不一定能明确界定“城市”与“非城市”区域的固定边界(图10)。

2.2 研究背景

上述内容为腹地理论的提出提供了背景。然而,关注腹地不仅仅是为了解决这些非城市地区面临的问题,还要认识到它们对可持续发展的潜在贡献。将腹地纳入更广泛的城乡规划框架,可以促进更加平衡和包容的发展方式。这包括认识到城市与农村地区之间的相互依存关系,并制定支持腹地振兴和可持续发展的策略。这种关注的转变鼓励人们重新思考定义进步和成功的方式。不应将城市化视为发展的唯一指标,而应考虑所有地区的健康、可持续性发展和文化丰富性。这样可以创建一个更加公平和具有韧性的社会,既重视和发展城市中心,也重视和发展腹地。

综上所述,腹地地区具有以下特征。

(1)对社会运转至关重要,但往往在理论、政策和研究中被忽视。

(2)产生重大影响,并直接影响大部分人口。

(3)影响地表现象的力量越来越大。

(4)是一个具有适应性和可扩展性,与各种超出城市中心以外规模都有关联的概念。

(5)面临着独一无二的发展挑战,不同于严格意义上的农村或完全城市地区。

(6)旨在从起点了解和重新发展的现有结构。

(7)可以成为更大规模综合发展的修复地、营养地和资源地。

3 腹地理论

2012 年,由于过度关注城市地区而忽略了全球范围内的大量领土,作者试图提出另一种声音,于是组织了一场跨四大洲的、5 所大学参与的、为期24h 的研讨会,主题为“城市之外”。这个研讨会基于这样一种观点:以城市为中心的规划常常忽视了城市边界以外的地区。研讨会在引言中提出了关于城市增长与自然环境之间平衡的关键问题,强调了需要考虑城市之外的地区,以创造可持续的发展。最初这只是一个观点,但十多年后,它被视为承认非城市重要性的起点。借助本文的研究,这一简单的观点现在已发展为一个研究方向,该方向定义了学科中目前在客观和主观上都被忽视的领域。同时,它还为解决围绕城市和乡村定义的全球模糊性问题提供了一个有价值的框架。这一理论提出了一个梯度定义,而不是严格的二分法,并非固有的“优质 = 城市 、未开发 = 农村”框架。这种梯度定义也有助于人们更好地理解国际比较,因为城市的确切定义已不再重要。这个被忽视的领域目前可以通过它所面临挑战的类型、相对于城市和农村地区的位置等来描述。与严格意义上的城市或农村相比,这一介于两者之间的领域有着明显不同的需求和发展特征,无论是中国还是荷兰,以及世界上许多国家,目前都没有针对这一领域的具体政策或发展战略。人们称这一领域为“腹地”,相应的框架涉及“腹地科学的理论与实践”,以下简称“腹地”。腹地的概念包括“后方(通常被忽视或超出人们主要关注范围之外)”,以及“腹部土地(“腹地”中文定义的直接翻译)”的概念,承认了它在更大系统中不可或缺的作用。

3.1 从观察到理论和科学

在建筑、城市设计和规划领域,新理论框架的建立通常源于对社会文化的观察(图11)。从勒·柯布西耶(Le Corbusier)、多希阿迪斯到巴克敏斯特· 富勒(BuckminsterFuller)、吴良镛、库哈斯等人,有影响力的建筑师和城市规划师的一个共同点是:他们基于对当代社会的具体观察来建立综合理论。这些观察通常揭示了社会中隐藏或被忽视的方面,进而推动了新理论框架的发展,对建筑和城市设计实践产生了深远影响。本文旨在延续这一传统,提出对未来理论的基础性观察,而腹地可以被视为这些现代综合理论演进的下一步。

为了更好地理解这一点,可以回顾这些理论自现代以来的演变。勒·柯布西耶在其开创性的著作《明日之城及其规划》(The Cityof Tomorrow and Its Planning) 中, 提出了一种激进的现代城市化概念,以解决历史城市中不卫生、不健康和衰落的状况[22]。勒·柯布西耶对20 世纪初城市中心社会和环境问题的观察,使他设想了一种全新的城市,这种城市以功能性、效率与和谐为特征,强调绿地的重要性和与现代技术的融合。后来,在不同的时代和背景下,多希阿迪斯发展了人类聚居学理论。他通过系统的观察提出,人类聚落可以进行系统的研究。他在《人类聚落科学导论》(Ekistics: An Introduction to the Science ofHuman Settlements)中以概述的方法表明,通过仔细研究人类居住模式和功能,可以推导出一个理论,为更好的城市规划和聚落发展提供参考[6]。多希阿迪斯的工作为更科学的城市设计方法奠定了基础,强调需要全面分析和系统规划。另一个例子是巴克敏斯特·富勒,他因其创新和前瞻性的设计而著名,他同样也非常依赖于对社会问题的观察。在其著作《关键路径》(Critical Path)中,研究了他所处时代的环境和社会问题,并提出了旨在解决这些问题的建筑和城市规划解决方案[23]。他的系统方法寻求将技术和可持续实践整合到设计中,倡导人类需求与环境保护之间的协同作用。

在20 世纪70 年代,库哈斯提出了一种新颖的理论表述方法,即通过追溯过去的观察结果来构建他所谓的 “逆向宣言”。在《疯狂的纽约》(Delirious New York)中,库哈斯利用曼哈顿的历史和当代现象,制定一个理论框架,这一框架也成为他未来建筑和城市设计项目的重要指导[24]。这项工作成为他在OMA 实践的基础,展示了历史分析如何为当代设计提供信息。随后在中国,吴良镛基于多希阿迪斯的研究,并结合自己的观察,提出了一种基于对社会快速发展观察的各种理论的整合。他提出的人居环境科学理论,强调通过一系列嵌入式尺度来研究人类与其周围环境的关系。吴良镛的方法结合了中国传统规划原则和现代城市设计,创建了一个在快速城市化背景下可持续发展的综合框架。最近,库哈斯的作品《乡村:一份报告》(Countryside: A Report)在纽约的古根海姆博物馆举办了展览,延续了基于观察的发展理论的传统[2]。库哈斯探讨了经常被忽视的乡村和非城市区域,强调这些地区正在发生的重大变革。他的工作突破了传统的城市中心视角,呼吁人们对全球景观进行更包容的理解,认可城市与乡村环境之间的动态互动。

综上所述,这些建筑师和城市规划师通过仔细观察社会变化,发展出指导建筑和城市设计实际应用的强大理论。这些理论甚至演变成新的科学领域,如多希阿迪斯和吴良镛的案例。他们的工作强调了不断重新评估和调整人们对建成环境的理解,以应对当代挑战和机遇的重要性。此外,建筑师作为关键社会现象的观察者,有能力将这些现象转化为具有明确实用价值和应用潜力的综合理论,他们的技能也是如此。这也是本文的灵感和目标所在。

3.2 腹地叙事背景

关于腹地的具体叙述,前文已确立了城乡之间长期存在着明显的分化,这种分化并不局限于现代化或城市化。这种思维方式在大多数知识、经济和文化领域中依然适用。为更好地应对腹地发展的挑战,需要考虑2.1 节中描述的挑战框架,并将其归类为几个主题。目前,这些主题并非旨在提供一个完整的概述,而是理论发展的起点,包括以下内容。

3.2.1 社会文化动态

腹地是一个非同质的、丰富的社会文化动态拼图,城乡文化在这里交织融合。这种融合产生了独特的表达形式,反映了对比鲜明的生活方式之间的共生关系。建筑师和规划师必须深入研究腹地的社会文化结构,才能设计出满足这些过渡区域内社区多样化需求和愿望的空间。

3.2.2 经济相互依存

对腹地的反思包括认识到错综复杂的经济之间的相互依存关系。这种关系体现在不同的层面上,既可能涉及城市中心、周边腹地和乡村之间的关系,也可能涉及城市内部相对欠发达的地区。腹地不仅仅是资料、产品或资源的来源,还在相互依存的经济体系中发挥着关键作用。理解和利用这些相互依存关系对建筑师和规划师制定可持续性和弹性的开发策略至关重要。

3.2.3 生态综合

腹地作为一个未被察觉或未被关注的区域,是城市与农村生态系统交汇的枢纽。这些过渡区的生态环境对于促进环境可持续性发展至关重要。建筑师和城市规划师必须考虑其设计对自然环境的影响,并致力于推广促进生物多样性、资源保护和生态平衡的解决方案。

通过这种方式,本研究旨在确定适用于腹地的特定建筑(和城市)设计方法。

4 腹地实践

除了理论框架之外,腹地也是建筑师和城市设计师可以通过实践进行干预的地方。为说明可能的实际应用领域,下文列举了各种实例。这些实例分为两部分:第一部分是在中国背景下定义的腹地领域,结合了与前述的社会文化动态、经济相互依存、生态综合3 点框架相关的主题领域。第二部分是一小部分经验案例,是过去几年中笔者参与相关课题的成果,同时也是理论框架的发展。它们不是对研究的完整概述,而只是为了说明可能的研究范围、领域的潜力和实际意义。

4.1 该理论的可能研究范围

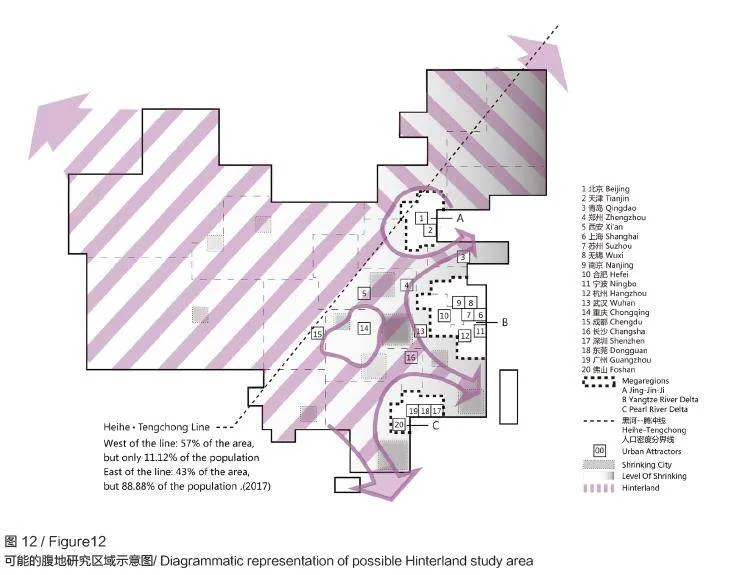

考虑本刊作为中国领先的双语期刊,以下列出了一些可能的腹地研究主题及其在中国的应用领域。首先,可以在图12 中看出国家尺度下的腹地可能涉及的区域,这是一个辽阔的土地区域,没有确切的边界,在这个区域内仍然存在着大量不同的情况,但可以根据该理论框架进行描述,而且在普遍论述范围之外,也没有通用的政策或具体方法。这个区域通常不包括大型城市群和大多数收入较高的沿海地带,而包括许多县城、衰落的城镇,以及许多三线及以下城市。

为说明该理论在这一领域内的可能性应用,下面列举了一些已经或可能适合应用研究的具体研究领域及其子课题。

4.1.1 关于社会文化动态

子课题:城市周边问题

案例区域:上海郊区

尺度:城市

理论依据:上海作为一个快速发展的城市,拥有广阔的城市周边地区,这些地区描绘了城市发展与农业景观之间的画面。城市扩张与传统农村土地利用之间的冲突在城市周边地区随处可见。

4.1.2 关于经济相互依存

子课题:经济转型

案例区域:浙江省宝溪县

尺度:县域

有趣的是,正如库哈斯在2019 年指出的,“中国是目前唯一一个制定政策,将农村作为一个有活力的环境,作为一个创造新机遇的地方的国家”。在腹地和龙泉国际竹建筑双年展中(图13),由当地艺术家葛千涛和建筑师国广乔治(George Kunihiro)策划的活动就是一个极好的例子。该展览探索竹子和泥土的使用,以支持原生态的生活方式,结合了本地供应商、国际策展人以及适合当地环境的多功能建筑师。在参观完项目后,拉扎洛娃(Lazarova)在《建筑评论》中写道:“这些设计重新将塑造对世界的文化影响,利用这些知识为世界带来了新的东西[25]。”这是腹地中关于经济转型的一个很好的例子。

4.1.3 关于生态整合

子课题:气候影响与生态整合

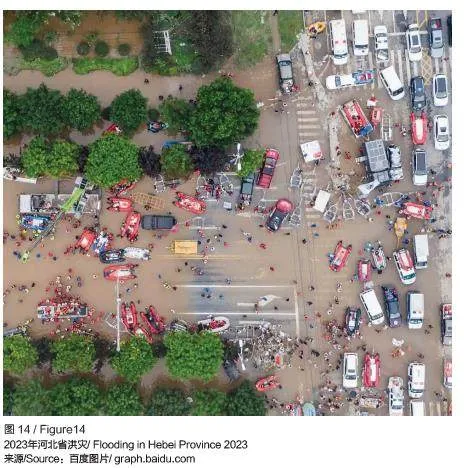

案例区域:河北泛洪区(包括北京和雄安周边地区)

尺度:地区

理由:正如前文所述,如果身处城市,几乎不会注意到气候危机带来的严重影响。但是如果身处腹地,就会意识到天气异常,不得不面对真实的后果。天气变得越来越极端,而城市太宝贵不能被牺牲。因此,周围的腹地被牺牲,用于水源缓冲或洪水防治。这可能挽救了城市中数百万人的生命和数10 亿美元的 GDP,但也猛烈地摧毁了不幸的腹地居民的日常生计。2023 年,河北省的大片区域被有意淹没(图14),以缓解天津、北京、河北地区城市中心的压力和潜在灾难。像这样使用缓冲区域的做法当然不仅限于中国,事实上,荷兰也使用了非常类似的策略,但至关重要的是,不仅要从城市群自上而下的需求出发,还要从居住在这些地区的当地居民的角度来考虑,荷兰在这方面已经有了很好的经验。

4.2 近期实践应用

第二部分是笔者在过去几年中亲自参与相关课题的一小部分经验应用,同时也是理论框架的发展过程。

4.2.1 为可持续发展重新发现古老道路

古道联合研究与设计工作室将可持续旅游业发展与腹地地区的社区振兴相结合,体现了腹地理论的实践应用。这一持续的合作倡议由北京清华大学和秘鲁利马的教皇天主教大学(the Pontifical Catholic University)共同主办,同时还有来自瑞士苏黎世联邦理工学院和西班牙马德里理工大学的研究人员参与。该倡议专注于古老的非机动车道系统,将其作为可持续发展的模板。旨在展示特定主题如何在世界各地不同的腹地地区中以类似的条件出现,并采用当地条件的相似策略。首个调查地点是著名的印加古道系统,或称为Qhapac Ñan,横跨南美多个国家,总长超过2 万km2。该项目的目标不仅局限于欣赏历史,还包括了解定居模式、当地条件和社会结构,为在不断变化的环境条件下可持续发展奠定基础。

该项研究的目的在于保护历史遗产,并展望其演变和适应性发展。通过对周边景观进行深入地测绘和探索,研究团队发现了这些古道与塑造它们的社会结构之间错综复杂的联系。这种理解为创新设计方案提供了依据,将遗产保护与适应性相结合,确保这些历史路网在面对气候变化和地貌变迁时,仍具有现实意义。一个重要的关注点是与这些景观相关社区的福祉,探讨低影响旅游如何作为促进积极变革的催化剂,同时造福环境和当地居民。这些设计旨在平衡经济增长与文化和自然遗产保护之间的关系,促进社区福祉。

虽然最初的研究专注于印加古道系统,但该框架是在全球背景下设定的,认识到古今中外各种文化中都存在类似的系统,最终形成全面的比较战略分析。调研的下一阶段将集中在中国的古茶马道上,这是一条历史悠久的道路,在类似的山区利用马匹促进茶叶和其他商品的交易,塑造了地区经济,并促进了文化间的联系。通过研究这些古道,工作室旨在了解它们的全球意义,并探索如何利用它们激发全球可持续性发展实践。这项正在进行的研究旨在对抗文化侵蚀,强调将历史遗产与可持续发展相结合的重要性,并为全球腹地振兴提供宝贵的经验。

4.2.2 腹地未来的生活方式

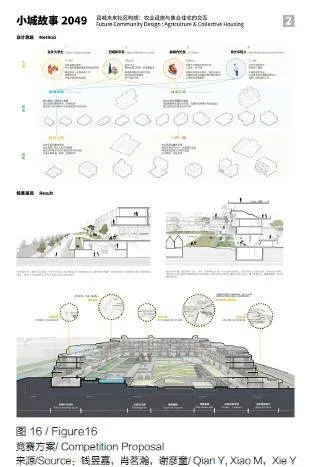

在这个项目中,3 名学生在笔者的指导下,参加了一个全国学生自选地点竞赛,并获得了荣誉奖。本项目决定选择以县城为主题,尽管县城经常被忽视,但县城人口却占中国总人口的约19%。进一步的分析显示,县城的人口正在减少,它们的发展战略和配套设施相对落后。另一方面,县城也有其发展的优势和潜力。与大城市相比,县城的生活节奏较慢,压力较小,消费也更为实惠;与农村地区相比,它们可以提供相对更加密集和完善的生活服务,如教育和医疗。

因此,县城为腹地战略的应用提供了一个绝佳的主题,并通过总结县城在城市和农村地区之间的优势来实现。本项目选取了中国四川省一个典型的县级城镇,这也是其中一名学生的家乡,选择了一个具体的地点来设计一个综合社区区块,以展示腹地生活方式的潜力。设计的目标是将小规模农业与复杂多样的人口结合起来。在最终的竞赛作品中,学生们通过农业设施和生活与工作的融合,设计了一个互动、轻松且高品质的生活体验,为来自不同背景的人们打造了一个具有县城特色的未来社区。

这个未来社区设想为一个可以适应各种类似条件的原型,在这个原型中,未来社区由一系列 U 型庭院组成。这样的庭院具有很高的适应性,可以根据不同的场地和需求进行改造。不同的住宅单元组合形成了庭院的东、西、南、北4 个方向的建筑。庭院内布置有果树、稻田、菜地和畜牧等农业区,供居民共同使用。这些区域不仅为居民提供日常生活必需品,还可以成为居民共同劳动和交流的纽带。所有这些都凸显了“未来社区设计:以集体农业为新生活方式”的雄心(图15,图16)。

5 结语:为腹地综合科学铺路

总之,本文提出建立一个“腹地科学”的研究计划,提出了一个概念框架,用以定义、理解和引导建筑与城市规划领域的过渡空间。本文通过将理论见解与实际应用相结合,展示了这一科学如何在各种背景下建立、关联并适用。

受到“腹地”一词中文翻译为“腹部土地”的启发,腹地框架强调了这类空间作为整体中重要但隐蔽的本质。这一定义是分形理论的基础,适用于从全球视角、区域和城市到邻里和单个建筑的多个尺度。本文通过整合重要的建筑和城市规划理论,并借鉴案例研究来说明腹地地区所面临的挑战。本文为综合的、适应性强的 “腹地科学(包含复杂的过渡空间)”奠定了基础,这一科学计划旨在弥合城市与农村之间的分化,为当代城市化提供一种更加全面和细致的方法。

腹地通常代表隐藏在容易被看见或感知背后的区域,为解决全球对城市和农村地区缺乏统一定义的核心问题(这一问题妨碍了国际比较)提供了一个有价值的框架。通过为城市与农村空间的衔接提供一个新的范例,本文主张更深入地理解和认识腹地的潜力。这种方法不仅能应对当代城市化的挑战,还能为可持续的创新设计方案提供可能性,从而提高城市和乡村居民的生活质量。

通过这种方式,腹地科学为未来充分认识和驾驭这类过渡空间的复杂性铺平了道路,促进了一种平衡和综合的发展方式,造福世界各地的不同环境和社区。

参考文献

[1] MVRDV. KM3:Excursions on capacities [M].Barcelona: Actar,1899.

[2] AMO, KOOLHAAS R. Countryside a report[M].Köln: Taschen, 2020.

[3] RAWORTH K. Doughnut economics: seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist[M]. London: RandomHouse Business Books, 2017.

[4] CHISHOLM G G. Handbook of commercial geography[M]. London: Longmans, 1911.

[5] Naciones Unidas. World urbanization prospects: the 2018 revision[R]. New York: United Nations,2018.

[6] KOJIMA R. Urbanization in China[J]. The Developing Economies, 1995, 33(2): 151-154.

[7] DIJKSTRA L, POELMAN H, VENERI P. The EUOECD definition of a functional urban area[EB/OL].(2019-12-11)[2024-05-11]. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/urban-rural-and-regional-development/the-eu-oecddefinition-of-a-functional-urban-area_d58cb34d-en.

[8] DOXIADIS C A. Ekistics: an introduction to the science of human settlements[M]. New York: Oxford University Press, 1968.

[9] 吴良镛. 人居环境科学导论[M]. 北京: 中国建筑工业出版社, 2001.

[10] SHOP Gestalten E. The rebirth of China’s hinterlands[EB/OL]. (2021-02)[2024-05-07]. https://gestalten.com/blogs/journal/the-rebirth-of-china-shinterlands.

[11] DELGADO-VIÑAS C, GÓMEZ-MORENO M L. The interaction between urban and rural areas: an updated paradigmatic, methodological and bibliographic review[J]. Land, 2022, 11(8): 1298.

[12] GUAN X L, WEI H K, LU S S, et al. Assessment on the urbanization strategy in China: achievements,challenges and reflections[J]. Habitat International,2018(71): 97-109.

[13] CARSON D A, CARSON D B, ARGENT N. Cities,hinterlands and disconnected urban-rural development:Perspectives from sparsely populated areas[J]. Journal of Rural Studies, 2022(93): 104-111.

[14] WELSH J. Cities, hinterlands, and critical theory[J].Political Geography, 2018(65): 161-163.

[15] 蒲清平, 马睿. 国家战略腹地建设的内涵特征、重大意义和推进策略 [J]. 重庆大学学报( 社会科学版),2024, 30 (4): 37-48.

[16] FRANKOPAN P. The earth transformed: an untold history[M]. New York: Knopf, 2023.

[17] MCKAY G. Architecture myths #33: served and servant spaces[EB/OL]. (2022-11-20)[2024-05-07].https://misfitsarchitecture.com/2022/11/20/architecturemyths-33-served-and-servant-spaces/.

[18] NIJHUIS S. Home[EB/OL]. (2024-05-03)[2024-05-07]. https://steffennijhuis.nl/.

[19] XINHUA. ‘Countryside, The Future’ exhibition highlights China’s dramatic rural revitalization[EB/OL].(2020-02-27)[2024-05-07]. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202002/27/WS5e572f51a31012821727abe9.html.[20] BAYER. Farmer voice survey[EB/OL]. (2023-10-12)[2024-05-07]. https://www.bayer.com/sites/default/files/FarmerVoiceSurvey2023.pdf.

[21] ZHAI S Y, SONG G X, QIN Y C, et al. Climate change and Chinese farmers: perceptions and determinants of adaptive strategies[J]. Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 2018, 17(4): 949-963.

[22] CORBUSIER L. The city of tomorrow and its planning[M]. London: John Rodker, 1929.

[23] BUCKMINSTER F R. Critical path[M]. La Mesa:St. Martin’s Griffin, 1982.

[24] KOOLHAAS R. Delirious New York: A retroactive manifesto for Manhattan[M]. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

[25] LAZAROVA J. Bamboo has a fragile form of beauty,but in reality, in terms of tensile capacity, culms arestronger than steel[EB/OL]. (2017-03-01)[2024-05-07].https://www.architectural-review.com/buildings/bamboohas-a-fragile-form-of-beauty-but-in-reality-in-terms-oftensile-capacity-culms-are-stronger-than-steel.\

ORIGINAL TEXTS IN ENGLISH

Proposal for a Science of the Hinterland

DE GEUS Martijn

1 What is the Hinterland?

During my time in practice and academia, I haveobserved a significant dichotomy between urban andrural areas within the discourse of architecture andurban planning, which often marginalizes the nonurbanregions. During my formative years at TUDelft, cities, density and urban development werethe ultimate aspiration, expressed and celebratedin Koolhaas’s Delirious New York, the success ofhis Office for Metropolitan Architecture, books likeMVRDV’s ‘KM3: Excursions on Density’, and soforth[1]. Though in the past two decades a waningparadigm shift can be observed, even by some of thesesame individuals, to put more focus on the oppositeof ‘urban’, for instance in ‘Countryside: A Report’ [2],upon closer inspection this dichotomy still seems toremain intact. In my opinion this waning paradigmshift seems still insufficient, and incomplete. Hailingfrom the Netherlands, a country characterized bythe absence of distinct urban and rural boundaries inthe typical global definition, and having extensivelyexplored various regions in China and other places,I have observed a type of in-between realm, whichdefies the strict dichotomy, where a significantsegment of the population reside outside major urbanareas but not in traditional strictly rural settings. InChina alone, this area accounts for ca. 30% of thepopulation, and a significant share of GDP. And, eventhough besides ‘Metropolitan Offices’, we now alsohave various ‘Rural Practices’, there seem to be no‘Office’ or ‘Theory’ for the ‘In Between Areas’. Yet.

This proposal for a Science of The Hinterlandthus stems from the recognition of a crucial yet oftenoverlooked area in the discipline of architecture andurban planning: the transitional spaces that existbetween urban centers and rural landscapes. Asurbanization continues to reshape our environments,there is a growing need for a specialized theory thatnavigates the complexities of these intermediate zones.This also fits in with a growing tendency in boththe theoretical positioning and in the social culturalsphere to provide an alternative to the pursuit of‘more urbanization’. Whether from the perspective oftheories such as the ‘Doughnut Economy’ [3]that defiesa pursuit of constant (urban) growth or initiativeslike the Rural Revitalization Practice in China,that focuses on the development of China’s lesserdeveloped countrysides, there is an increasing focuson issues ‘Beyond the City’, that aim to tie togethera broader perspective of human development and thesurrounding environment. This paper aims to lay thefoundation for such an alternative, comprehensivetheory in the discipline of architecture and urbandesign, beginning with a proposed definition inspiredby the Chinese translation for Hinterland, 腹地 (fùdì).This definition serves as a conceptual anchor for afractal theory that can be applied consistently across various scales, providing a holistic understanding ofthis previously hidden Hinterland.

1.1 Definition

As for the definition of this term, originally‘Hinterland’ is a German word, that literally translatesinto English as ‘the land behind’. Its use was firstdocumented by the geographer George Chisholmin his Handbook for Commercial Geography[4].In English the definitions vary slightly betweenAmerican and British English. For our purpose wetake the American definition as the base, describingit as ‘an area lying beyond what is visible or know’,with the added definition for ‘any sparsely populatedarea where the infrastructure is underdeveloped’. Whentranslated to Chinese, Hinterland becomes ‘ 腹地’(fùdì), literally meaning ‘the abdomen lands’. As such itdescribes a type of land that is ‘hidden and important’,like the organs (abdomen) of a body. This abdomen hasseveral characteristics, of which the most important oneis that we cannot live without it. In contrast to missinga limb for instance, a human cannot survive withouta heart, brain and abdomen. In addition, in Chinesemedicine theory, the abdomen is given a restorativefunction. The body, and likewise a region or country,is thus believed to use the “ 腹” (abdomen) to storeenergy and to (physically) restore from there.

For this proposal, we consider the Hinterlandsimultaneously as defined by ‘the land behind’, i.e.typically ignored, lying beyond our main focus andinterests, as well as through its definition as the‘abdomen land’, acknowledging the Hinterland’scharacter as an essential organ of a larger system.

1.2 The Hinterland in the Context of Architectureand Urban Design

Applying the term “Hinterland” to the disciplineof architecture, urban design, and planning requires acontextual exploration of urban and rural definitionsand insights from key theories in these fields. Thisexploration aims to establish a nuanced frameworkto address the unique characteristics and challengesof intermediate spaces. This framework will serveto describe the base conditions for the ‘Theory andPractice of a Science of the Hinterland’.

First, its important to acknowledge that researchon urban-rural classifications has revealed a lackof a globally accepted definition, which hindersinternational comparisons and underscores the needfor a refined framework. For instance, currently, theUN reports figures based on nationally defined urbanshares. The problem is that countries adopt verydifferent definitions of urbanization. Not only do thethresholds of urban versus rural vary, but the types ofmetrics used also differ. Some countries use minimumpopulation thresholds, others use population density,infrastructure development, employment type, orsimply the population of pre-defined cities. This meansthat what a country like Denmark considers urban(200 inhabitants in a settlement)[5], is very differentto a country like China, where an area is urban if ithas more than 20,000 inhabitants [6], or Japan, whereit starts at 50,000[5]. If using China’s definition inDenmark, there are perhaps only very few ‘urban’areas, vice versa when applying the Danish definitionto China, almost the entire country could be called‘urban’ (figure 1). Some recent high-level Europeanpolicy studies tried to consider these challenges,by highlighting the definition gaps, and aiming toprovide a scholarly, interdisciplinary and designbasedframework for future development. In 2020, Iteventually led to a recommendation on the method todelineate cities, urban and rural areas for internationalstatistical comparisons, coordinated by LewisDijkstra (European Commission (EC), Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy) and wasjointly developed by six international organisations:the European Union, The Food and AgricultureOrganization of the United Nations (FAO), theInternational Labour Office (ILO), the Organizationfor Economic Co-operation and Development(OECD), the United Nations Human SettlementsProgramme (UN-Habitat) and the World Bank, bya variety of scholars[7]. The proposal in this paperbuilds on some of these recommendations. The ECcoordinated recommendation proposes a new method,called the Degree of Urbanisation, which classifiesthe entire territory of a country into three classes: 1)cities, 2) towns and semi-dense areas and 3) ruralareas. In this paper proposal I refer to this second, inbetween area, as ‘The Hinterland’. It generally fitswith the observations from the recommendation, buttakes it one step further by acknowledging it as aspecific territory. By addressing the lack of a universalglobal definition of urban and rural areas, theHinterland framework could offers a valuable tool forinternational comparisons and planning without theneed of a strict universal definition on the urban-ruralclassification. The Hinterland framework in fact aimsto challenge the traditional dualistic stance of Ruralvs. Urban. The evolving dynamics of contemporaryurbanization and its relation to surrounding ecologiesdemand a nuanced understanding of the transitionalzones between bustling urban centers and serene rurallandscapes. The proposed redefinition of the term“Hinterland” encapsulates the multifaceted natureof these intermediate spaces. This conceptual shiftfosters a more inclusive and holistic approach toarchitecture and urban planning, acknowledging theintricate interplay between urban and rural elementsin shaping our built environments.

Secondly, though the Hinterland Science in itselfis a new framework, within the realm of architectureand urban design, existing theories that have foundtheir origin in similar observations of contemporarydevelopments can be a good base for framing thedevelopment potential of the hinterland in the contextof architecture and urban design. For instance, thetheories of Ekistics and Human Habitat (1968)proposed by Doxiadis offer valuable perspectiveson the interactions between human settlements andtheir environments[8]. Further insights can be drawnfrom Wu Liangyong’s work on the Sciences ofHuman Settlements in China [9], which provides acomprehensive understanding of the complexitiesinherent in the development of human habitats.These well-established theories lay the groundworkfor conceptualizing the Hinterland not merely as ageographical space but as a dynamic and transitionalrealm where urban and rural elements converge.Synthesizing these theoretical underpinnings withempirical research is essential for informing a holisticand adaptive approach to contemporary urbanization.In addition, there is evidence of a rebirth in certainHinterlands. For example, Feng describes how theChinese countryside is being revitalized with markets,libraries, and hotels[10]. Other significant observationsof this realm include Delgado-Vinas’s explorationof urban-rural interactions [11],Lu’s assessment ofChina’s urbanization strategy[12], Carson’s study ondisconnected urban-rural development[13], and JohnWelsh’s critical theory approach[14].These studieshighlight the dynamic nature of Hinterlands and theirpotential for innovation and regeneration.

Lastly, the strategic importance of Hinterlandshas gained recognition in recent policy discussions. InDecember 2023, the concept of “building the nationalstrategic hinterland” was introduced at the CentralEconomic Work Conference in China. Accordingto Pu and Ma (2024), this concept aims to optimizeproductive force distribution and safeguard national security by delineating key geographical attributesand strategic characteristics of Hinterlands[15]. Thenational strategic hinterland possesses fundamentalcharacteristics such as pivotal geographical location,robust economic resilience, and its role as an engine forinnovation and development. It fosters urban culturecohesion and represents a new growth pole and powersource for economic development. To translate strategicdecisions into tangible results, systematic promotionof the national strategic hinterland’s construction isimperative. This includes enhancing top-level strategicplanning, coordinating the establishment of strategicmaterial reserves, supporting strategic scientific andtechnological capabilities, and developing a networkof strategic transportation capacity. By doing so, theHinterland can continuously promote high-qualitydevelopment and advanced security infrastructureconstruction in the new era.

By redefining the Hinterland in the context ofarchitecture and urban design, we acknowledge itsunique role and potential in shaping sustainable andresilient human settlements. This framework offersa comprehensive approach to understanding andaddressing the complexities of these intermediatespaces, fostering innovation and adaptability in urbanand rural planning.

1.3 An Ignored realm

If we look at the existing research into this‘abdomen land’, when taken the CKNI database ofChinese publications as a reference, we can see that indisciplines like economics, infrastructure, agriculture,political science, etc, this realm is studied quiteextensively, with publications steadily growing, arapid rise and peak around 2008. There’s considerablecontinued interest after that, with an expected risein research for the coming years, given the remarksfrom the 2023 Central Economic Work Conference( figure 2). However, despite this significant generaland political interest, in the field of building science,building engineering, architecture and planning itreminds an ignored realm in itself, accounting for lessthan 1,5% of papers in this field (figure 3). You wouldexpect that our discipline, with its ability to shapethe build environment, its ability to connect humanswith habitats, is heavily involved in the researchand development of this realm. But, it couldn’tbe further from the truth. In his 2020 publication,“Countryside, A Report,” architect Rem Koolhaasacknowledges this deficit, and describes this as “AnIgnored Realm”[2]. He describes how various politicalleaders, and societies through human history havepaid great attention to the hinterlands, but how in ourcontemporary (Western-inspired) urban societies thishas become forgotten and ignored[2].

Shifting his focus away from the freneticenergy of urban life, Koolhaas illuminates thehidden transformations occurring in these non-urbanareas, challenging conventional perceptions andrecognizing their significance. Koolhaas underscoresthat the urban way of life has profoundly influencedthe organization, abstraction, and automation of thenon urban, what he calls ‘the countryside’ on anunprecedented scale. This transformation has resultedin significant political and social redesigns drivenby ambition, vision, and political will. The globalcountryside where he is reporting from in the book,in this context, is not merely a passive backdropto urban centers but a dynamic and evolving realmshaped by complex forces. Koolhaas’s work revealsthis realm as a frontier for experimentation, wherenew social structures and innovative practices emergeacross various countries and contexts. The conceptframework of the Hinterland proposed in this paperfits seamlessly into Koolhaas’s defined territory ofthe “ignored realm”, and in fact, is probably a morefitting definition, since ‘countryside’ has particulardefinitions tied to rural life. Instead, the Hinterlandrepresents a space of potential and transformation,challenging traditional notions of rural life. It’s layereddefinition of the ‘abdomen land’ further acknowledgesthe restorative potential and the vital importanceof this ignored realm. As such, by documentingand analyzing the on going changes in this realm,Koolhaas provides critical insights into the evolvingnature of this Hinterland. His observations revealthat the Hinterland is not static but a dynamic areaundergoing significant shifts, driven by new forms ofsocial organization and technological advancement.

Koolhaas’s work serves as a crucial record of lifebeyond the cities, offering valuable evidence of thetransformative processes underway in these areas. Hisfindings are instrumental for understanding Hinterlandsituations worldwide and provide a foundation forevaluating and innovating within these often overlookedand dynamic landscapes. In essence, Koolhaas invitesus to reconsider our preconceived notions of thisIgnored Realm. He highlights its capacity for change,adaptability, and innovation, prompting architects,urbanists, and policymakers to view the Hinterland notas a static rural expanse but as a realm rich with potentialand possibilities. This perspective is essential foraddressing the challenges and opportunities presented bythe Hinterland in the context of sustainable developmentand urban-rural dynamics. Koolhaas’s insights push theboundaries of how we perceive and engage with theHinterland, advocating for a more nuanced and forwardthinkingapproach to its study and development. Hisresearch not only underscores the need for a definition ofthis non-urban territory, but also shows the wide varietyof topics that fall in this area that are not yet covered byour current discourse.

1.4 The Historical Context of The Hinterland

Now, we often think that urbanization is a typicalmodern phenomenon. However, it is not. To furtherunderstand how this ‘urban lt;-gt; non-urban’ relationhas been changing over the past millennia, and howthis has lead to the establishment of the non-urban as arelatively ‘Ignored Realm’, and with typically negativeconnotations, we shall look at the historic evolutionof this dynamic. In ‘The Earth Transformed’ (2021)Oxford professor of Global History, Peter Frankopandescribes how ‘wealth disparities became a signatureof the populations that urbanized earliest and mostintensively’, which then created a model of the city asa parasite, where growth was powered by the labourforce and the benefits harvested by an elite who set upand maintained barriers to cement their own positionsand restrict access at the same time[16]. Frankopandescribes how the relationship between cities, thecountryside, and the Hinterland has undergonesignificant transformations throughout history, shapedby economic, social, and environmental dynamics[14].In ancient China for instance he describes how,during the Qin Dynasty, there was a concerted effortby officials to tie the labor force to the land, ensuringhigh agricultural production. This was achieved bymaintaining registers to prevent peasant mobility,effectively binding workers to their agrarian roles.This approach underscores the historical relianceon agricultural labor to support urban centers andthe state’s broader economic stability. Philosophicalperspectives from ancient Greece and Rome furtherillustrate the urban-rural dichotomy. Socrates, asrecounted by Plato, “there was nothing to be learnedfrom trees, nature and the countryside; the only placeone could gain knowledge was in the city, from othermen.” Socrates thus dismissed the countryside as asource of knowledge, emphasizing the city as thesole place of intellectual growth. In contrast, Ciceroromanticized agriculture as an ideal pursuit, yet he overlooked the harsh realities faced by those whofarmed for their livelihood. This idealization of rurallife often masked the exploitation and backbreakinglabor endured by agricultural workers.

Throughout history, urban and rural areashave not only been interconnected through laborand economic dependencies but also throughenvironmental reconfigurations. The movement ofplants, animals, and agricultural techniques acrossregions was driven by human needs and desires,reshaping the environment to suit urban and ruraldemands alike. The Han Dynasty in China, forexample, saw officials introducing land-reclamationtechniques and new tools to enhance agriculturalproductivity, paralleling similar developments inother parts of the world, such as Rome. Urbanizationalso brought about significant ecological and healthchallenges throughout history. Pliny the Elderlamented humanity’s overexploitation of nature forself-enrichment, warning of environmental backlashin the form of natural disasters. Urban areas all overthe globe, with their dense populations and oftenunsanitary conditions, became breeding groundsfor disease, further complicating the health andsustainability of city life. The historical narrative alsohighlights the resilience and adaptability of differentregions in response to environmental and sociopoliticalpressures. In parts of Europe, innovations inagricultural practices and a shift towards pastoralismhelped communities adapt to changing climates andexternal threats, such as barbarian invasions. Theseadaptations fostered local self-sufficiency, providingbuffers against food shortages and other urbanvulnerabilities. Arab scholars, drawing on Greekthought, examined how environmental conditionsinfluenced human characteristics and societaldevelopment. These perspectives underscored thebelief that climate shaped not only physical attributesbut also cultural and intellectual traits, reflecting abroader understanding of the interconnectednessbetween environment and human society.

Overall, the historical evolution of therelationship between cities, the countryside, and theHinterland reveals a complex interplay of economicexploitation, philosophical ideals, environmentalmanagement, and adaptive resilience. Thesehistorical insights are crucial for understanding thecontemporary challenges and opportunities in definingand navigating the Hinterland in architecture andurban planning. A good example of this changingperspective and its relation to the definitions ofarchitecture and urban planning can be visualizedby studying the scroll ‘Along the River during theQingming Festival’, widely regarded as the mostimportant Chinese painting. Figure 4 shows a plandepiction of the content focus of the scroll, it showsa focus on the in between. In between City andCountryside, depicting the Hinterland. Various versionsof this painting exist, covering a period of severalhundred years that further show the evolution of thedefinitions of cities, rural areas and the in between.

1.5 A Fractal Theory

Building upon the proposed definition of theHinterland as 腹地 (fùdì), the author proposes anapplication beyond just the realm of the ‘non-urban’.This paper aims to introduces the definition as afractal theory that applies consistently across variousscales. The Hinterland as an ‘abdomen’ area, of arelation between that what we see and that which ishidden beyond sight, but invaluable to the overalloperation of the system is something that can beobserved in various scales. It does not only applyto the literal ‘land’ definition of ‘Hinterland’. It canapply to the scale of countries, global regions, cities,campuses, even buildings. New relationships andstructures of Hinterlands are forming and this willraise the attention to different scale “Hinterland”, largescales for example (international, national, regionaletc.), and smaller scales for example (neighborhood,campus, service institutions etc.), see figure 5.

For instance, at the global level, the Hinterlandis characterized as transitional zones between majorurban centers and remote rural areas. This definitionextends to regional and local scales, encompassingperi-urban areas and other intermediate zones. Thefractal theory further penetrates the micro-scale,influencing the design and definition of individualbuildings within the Hinterland. And even at thebuilding level, it could be described in this way, andin this regard resembles Louis Kahn’s definition ofthe ‘served and service spaces’[17]. By embracinga fractal approach, the Science of the Hinterlandacknowledges the interconnectedness of thisprinciples across scales, facilitating a comprehensiveand adaptable understanding of transitional zones,of hidden and ignored areas that are fundamental tothe functioning of the whole. For this paper we focuson the intermediate scale of cities, regions and theirperipheries to explain the core principles.

2 Why is it important?

According to the UN’s “World UrbanizationProspects: The 2018 Revision,” the world’s populationbecame more urban than rural for the first time in2007[5]. Today, over half of the world’s populationresides in cities, which occupy a mere 2% of theglobal land. Most of the research and practice inour discipline is focused on this 2%. The remaining98% of the world’s territory, however, constitutes thefocus of the proposed theory. This 98% encompassesvast expanses of countryside, rural territories, vitalinfrastructures, industries, county towns and wildlandscapes, largely untouched by urbanization (Figure 6 and 7). An image compiled by TU DelftProfessor Steffen Nijhuis, as presented during hisinaugural lecture, vividly illustrates this contrast (Figure 7)[18]. The hinterland operates as a dynamicrealm between urban hubs and rural expanses, offeringunique challenges and opportunities.

2.1 Challenges in the Hinterland

As we have shown, there has historically existeda strong division between the urban and the rural.Many societies have prioritized urban developmentover rural development, with the urban beingsynonymous with a higher and more civilized partof society. According to Frankopan , this divisionwas even the most important single reason for thedevelopment of hierarchical societies[16]. And to thisday, an increase in the urbanization rate of a particularcountry or area is used as a measure of development,with the UN stating that there is a correlation betweena country’s wealth and its urbanization rate. However,this tunnel vision on urbanization and the supposedpositive aspects has come under scrutiny. Koolhaas(2020), once a strong advocate of the urban himself,now states that today we don’t have a real, mutualrelationship between the urban and the non-urban[2]. Infact, this long focus on the importance of urbanization,cities, and urban lifestyles has led to some unwantedand undesirable side effects, that underscore theimportance of establishing a specific framework toaddress these. A first categorization of these currentproblems include, but are not limited too:

2.1.1 Alienation of the Non-Urban from the Urban

This alienation can be observed in the socialand cultural aspects, the distribution of resources,and the general dissatisfaction in rural areas. Thisdissatisfaction is also observed through the rise ofpopulist political parties and the spread of conspiracy theories based on the fear of being “left out” or“controlled by an urban elite” in Western countriesin Europe or in the US. This alienation exacerbatessocial divides and hinders cohesive nationaldevelopment.

2.1.2 Unsustainable Urbanization

Total urbanization raises questions aboutsustainability and the quality of life. Perhaps morewealthy on average, high-density urban areas cansuffer from overcrowding, pollution, and increasedvulnerability to diseases. Moreover, the pressureon urban infrastructure can lead to deterioratingliving conditions, high continuous stress levels anddepression rates, and a sharp decline in fertility. Thus,it is crucial to consider whether total urbanizationshould be the ultimate goal, and what alternativemodels might better balance human progress andquality of life, which would ultimately benefit societyat large. Li Xiaodong’s concept or ‘Rurbanization’(Figure 8) provides an interesting experiment in thisdirection of a specific development model that isapplied to the Hinterland area that doesn’t have thefinal goal to fully urbanize a former rural area.

2.1.3 Environmental Degradation

The intense focus on urban development hasalso often lead to the neglect, exploitation anddegradation of rural and natural areas. This canresult in deforestation, loss of biodiversity, and soildegradation. Hinterland areas are sometimes usedmerely as resource bases to support urban growth,without adequate measures to sustain their ecosystems.Urban areas and their residents themselves arequite shielded from the immediate effects of thisenvironmental degradation. Koolhaas, in an interviewwith China Daily in February 2020, accurately stateshow the environmental degradation and the resultingclimate changes can be much more observed in thehinterland: “If you’re in cities you barely notice kindof global warming. But (…), as soon as you go out ofthe city, you realize the weather is strange, or thereare irregularities in terms of expectation,” he said[19].Recent global studies shown that more than 70% offarmers have already seen large impacts of climatechange on their farm [20]. With 70.3% of farmers inHenan, China’s largest agricultural province with ca51 Million farmers, believing that climate changeposed a risk to their livelihood [21].

2.1.4 Economic Disparity

The economic focus on cities can exacerbatedisparities between urban and rural areas. Ruralregions may experience a lack of investment, leadingto limited economic opportunities and higher rates ofpoverty. This economic imbalance can fuel migrationto cities, further straining urban infrastructures,contributing to rural depopulation and exacerbatingthe problems mentioned above. This disparity canalso be observed in the availability of services andinfrastructure. Hinterland areas often have limitedaccess to healthcare, education, and transportation.Such disparities can lead to lower quality of lifeand hinder the potential for rural development andintegration into broader national progress.

2.1.5 Cultural Erosion

The 98% of non urban areas are often rich incultural heritage and traditions. The emphasis onurbanization can lead to the erosion of these culturalidentities as younger generations move to cities insearch of better opportunities, and it can erode adiversity of cultures typically found in this larger nonurbanhinterland. The migration influx can result inthe loss of unique cultural practices and communitystructures that have been maintained for centuries,now all merging into a single urban melting pot,losing their distinct heritage lineages.

2.1.6 Urban Hubris

There is a real danger of applying UrbanPrinciples to Non Urban contexts. Not everythingis a city, not everything needs to be a city, not everytown needs a museum. Not every village needs a hispeedrailway station with high rise offices. Not everyempty polder area has to have a data center. There is aproblem in which planners, architects and officials tryto utilize and implement urban strategies to develop orsolve non-urban problems. Instead we need to definea specific implementation strategy based upon anaccurate understanding and analysis of the situation,fitting with local needs, customs and requirements.Within the context of China, it’s striking to considerthat most of the important buildings, resources,architects and universities are all focused in the toptiered cities (megacities, super cities and large cities),which together account for less than 5% of totaladministrative entities ( figure 9). Leaving thousandsof other administrative entities which receive muchless specific attention, but are typically conceived ormodeled after the ‘success’ of higher ranked cities.Even though the administrative definitions do notnecessarily represent a fixed definition of ‘urban’ vs‘non-urban’ territories ( figure 10).

2.2 Research Context

This all together defines the context for thisproposed theory. However, focusing on the hinterlandis not just about addressing the problems faced bythese non-urban areas but also about recognizing theirpotential contributions to sustainable development. Byintegrating the hinterland into the broader frameworkof urban and rural planning, we can promote a morebalanced and inclusive approach to development.This involves acknowledging the interdependenciesbetween urban and rural areas and fostering policiesthat support the revitalization and sustainabledevelopment of hinterlands. This shift in focusencourages us to rethink the way we define progressand success. Instead of viewing urbanization as thesole indicator of development, we should considerthe health, sustainability, and cultural richness of allregions. By doing so, we can create a more equitableand resilient society that values and nurtures both itsurban centers and its hinterlands.

To summarize this intend, the Hinterland:

1.Is crucial for societal functioning but often neglected in theories, policies, and research.

2.Exerts significant effects and directly impacts a substantial portion of the population.

3.Represents an increasingly influential force shaping surface-level phenomena.

4.Is a concept, adaptable and scalable, with relevance at various scales beyond urban centers.

5.Faces unique development challenges distinct from strictly rural or fully urban areas.

6.Aims to understand and redevelop existing structures at its starting point.

7.Can be a place of restoration, nutrients and resources for integrated development at larger scales.

3 Towards A Hinterland Theory

In 2012, while trying to propose an alternativevoice to the excessive focus on urban areas, whichleft out significant amounts of territory around theglobe, the author organized a 24-hour workshopwith five universities across four continents, themed“Beyond the City.” This workshop was based on theobservation that urban-centric planning often neglectsthe areas beyond the city’s borders. The workshop’sintroduction posed critical questions about the balancebetween urban growth and the natural environment,emphasizing the need to consider what lies outsideand beyond the city to create a sustainable future.Being nothing more than an observation at first,more than a decade later it can be seen as a startingpoint of acknowledging the importance of the nonurban.Utilizing the platform of this paper, this simpleobservation has now grown to become a propositionfor a research direction that defines an area withinour discipline that is currently both physically andintellectually overlooked. At the same time, it offersa valuable framework for addressing the globalambiguity surrounding urban and rural definitions.Rather than a strict dichotomy, this theory proposesa gradient definition, without the stigmatic ‘quality= urban vs. undeveloped = rural’ outline. Thisgradient definition could also be helpful in betterunderstanding international comparisons, as it’s nolonger important what the exact definition of the urbanis. This ignored realm can now be described throughthe type of challenges it faces, it’s relative positionin relation to urban and rural areas, and so forth. Thisin between area has distinctly different needs anddevelopment characteristics than both the strictlyurban or the strictly rural, for which neither China,nor the Netherlands, like many countries around theworld, currently has a specific policy or developmentstrategy. This realm we refer to as ‘The Hinterland’,the accompanying framework concerns “The Theoryand Practice of a Science of the Hinterland” ( 腹地科学的理论与实践), ‘the Hinterland’ hereafter. Theconcept of the Hinterland encompasses both the notionof being “behind,” often disregarded or beyond ourprimary focus, of being ‘out of sight’ and the notion ofan “abdomen land” ( 腹地) a direct translation of theChinese definition of ‘hinterland’, acknowledging itsintegral role within a larger system.

3.1 From Observations to Theory and Science

In the field of architecture, urban design andplanning, the establishing of a new theoreticalframework often stems from social culturalobservations ( figure 11). From Le Corbusier andDoxiadis to Buckminster Fuller, Wu, Koolhaas, andothers, a common thread among influential architectsand urban planners has been their reliance on specificobservations of contemporary society to formulatecomprehensive theories. These observations, oftenuncovering hidden or overlooked aspects of society,have led to the development of new theoreticalframeworks that have profoundly impacted architecturaland urban design practices. It is in this tradition thatthis paper aims to propose a foundational observationsfor a prospective theory, and The Hinterland can beconsidered as a next step in the evolution of thesemodern comprehensive theories.

To understand this better, let’s take a look atthe evolution of these theories since modern times.With his seminal work, ‘The City of Tomorrow andIts Planning’ , Le Corbusier was a pioneer in moderntheories of urban development, in which he proposeda radical modern concept of urbanization to addressthe unhygienic, unhealthy, and dilapidated conditionsof historic cities[22]. Le Corbusier's observations of thesocial and environmental failings of early 20th-centuryurban centers led him to envision a new kind of citycharacterized by functionality, efficiency, and harmony,emphasizing the importance of green spaces and theintegration of modern technology. Later, in a differenttime and context, Konstantinos Doxiadis developedthe field of Ekistics. In which, through systematicobservation, he proposed that human settlements aresusceptible to systematic investigation. His approach,outlined in ‘Ekistics: An Introduction to the Scienceof Human Settlements’ (1968), suggested that bymeticulously studying the patterns and functions ofhuman habitats, we could derive a theory that wouldform the basis for better urban planning and settlementdevelopment[6]. Doxiadis's work laid the groundworkfor a more scientific approach to urban design,emphasizing the need for comprehensive analysisand systematic planning. Another example would beBuckminster Fuller, who, known for his innovative andforward-thinking designs, also relied heavily on hisobservations of societal problems. In his book ‘CriticalPath’ (1981), Fuller examined the environmental andsocial issues of his time and proposed architectural andurban planning solutions aimed at addressing thesechallenges[23]. His holistic approach sought to integratetechnology and sustainable practices into design,advocating for a synergy between human needs andenvironmental stewardship.

In the 1970s, Rem Koolhaas introduced anovel method of theory formulation by retroactivelyconsidering past observations to construct what hetermed a “retroactive manifesto.” In ‘Delirious NewYork: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan’ (1978),Koolhaas used the historical and contemporaryphenomena of Manhattan to develop a theoreticalframework that would also come to inform his ownfuture architectural and urban design projects[24].This work became a foundational pillar for hispractice at the Office for Metropolitan Architecture(OMA), demonstrating how historical analysiscould inform contemporary design. A little later InChina, partially based on his studies of Doxiadis,combined with his own observations, Wu Liangyongproposed an integration of various theories basedon his observations of rapid societal development.His theory of the *Science of Human Settlements*emphasized the relationship between humans andtheir surroundings through a series of embeddedscales. Wu’s approach combined traditional Chineseplanning principles with modern urban design,creating a comprehensive framework for sustainabledevelopment in rapidly urbanizing contexts. Mostrecently, Koolhaas’s work, ‘Countryside: A Report’(2020), accompanied by an exhibition at theGuggenheim Museum in New York, continues thistradition of observation-based theory development[2].Koolhaas explores the often-ignored rural andnon-urban areas, highlighting the significanttransformations occurring in these regions. His workchallenges the traditional urban-centric perspectiveand calls for a more inclusive understanding of theglobal landscape, recognizing the dynamic interplaybetween urban and rural environments.

All together, these architects and urban plannersdemonstrate how careful observation of societalchanges can lead to the development of robust theoriesthat guide practical applications in architecture andurban design. Sometimes these theories become newscientific domains, like in the case of Doxidadisand Wu. All together, their work underscores theimportance of continually re-evaluating and adaptingour understanding of the built environment to addresscontemporary challenges and opportunities, andsecondly the ability of architects as observers ofcritical social phenomena and their subsequent skillsto translation these into a comprehensive theory, withclear practical value and application potential. This isthe inspiration for the aim of this paper as well.

3.2 Hinterland Narrative Context

As for the specific narratives in the Hinterland,we have established that there has long been a strongdivision between the urban and the rural, whichis not tied to modernization or urbanization. Thisthinking still holds true today for a majority of ourintellectual, economic and cultural world. To addressthe challenges in the Hinterland accurately, we needto consider the framework of challenges as describedin 2.1, which we can then group in several topics.

These topics in no way aim to be a completeoverview at this point, but they are a starting point forthe theoretical development. They include;

3.2.1 Socio-Cultural Dynamics

The Hinterland, is a non-homogeneous, richtapestry of socio-cultural dynamics where urban andrural cultures intertwine. This convergence givesrise to unique expressions, creating a hybrid identityreflective of the symbiosis between contrastinglifestyles. Architects and planners must delve into thesocio-cultural fabric of the Hinterland to design spacesthat resonate with the diverse needs and aspirations ofthe communities inhabiting these transitional zones.。

3.2.2 Economic Interdependencies。

Rethinking the Hinterland involves recognizingintricate economic interdependencies. This plays out atvarious scales, it could relate to the interdependenciesbetween urban centers, the surrounding hinterlandsand the countryside, but it could also concern therelatively under developed areas inside city areas.Beyond being a source of materials, produce orresources at large, the Hinterland plays a pivotalrole in supporting interdependent economies.Understanding and leveraging these interdependenciesis essential for architects and planners to developsustainable and resilient development strategies.

3.2.3 Ecological Integration

The Hinterland, as an unseen or unknown area,is a nexus where urban and rural ecosystems intersect.Acknowledging the ecological significance of thesetransition zones is pivotal for fostering environmentalsustainability. Architects and urban planners mustconsider the impact of their designs on the naturalenvironment and aim for solutions that promotebiodiversity, resource conservation, and ecologicalbalance.

In this way, the research aims to aid inidentifying specificities for appropriate architecture(and urban) design approaches for the Hinterland.

4 Towards Hinterland Practice

In addition to the theoretical framework, theHinterland is also very much a situation in whicharchitects and urban designers can intervene throughpractice. For the purpose of illustrating possiblepractical application areas, a variety of examples areincluded below. They are grouped in two parts, first asection dedicated to the Hinterland realm defined in thecontext of China, combined with possible topic areasrelated to the previous three point framework. Thesecond part is a small selection of empirical examples,typically the result of personal involvement in relatedtopics over the past few years while simultaneouslydeveloping the theoretical framework. They are in noway a complete overview of topics, but merely aim toillustrate the possible range of topics, the potential andthe practical relevance of the research field.

4.1 Possible Scope of Research Fields withinthis Theory

Considering the functioning of this journal as aleading journal in China, with a bilingual output, listedbelow are some possible Hinterland research topics andtheir applications areas of these principles in China.First of all, the area of possible intervention that fallsunder this Hinterland on the scale of a country, can beseen in figure 12. It is a large land area, with no exactboundaries, within which there is still a large varietyof different conditions, but which can be generallydescribed according to the framework of the theory,and are at large outside of the general scope of thediscourse, and without a general policy or specificapproach. This area generally excludes the large urbanagglomerations, and most of the higher income coastalbelts, and instead includes many counties, shrinkingtowns and cities, as well as many 3rd and lower tiercities.

To show possible applications of the theorydomains within this territory, listed below are somespecific research areas with sub-topics that are alreadyare, or could be suitable for applied research.

4.1.1 Regarding Socio-Cultural Dynamics

Sub topic: Peri-Urban Conundrum

Example Area: The outskirts of Shanghai

Scale: Metropolis

Rationale: Shanghai, being a rapidly growingand urbanizing city, has expansive peri-urban areasthat depict the interface between urban developmentand agricultural landscapes. The clash betweenurban expansion and traditional rural land use can beobserved in areas surrounding the city.

4.1.2 Regarding Economic Interdependencies

Sub-topic: Economic Transitioning

Example Area: Baoxi, Zhejiang Province

Scale: County

Interestingly, as Koolhaas points out (2019)‘China is currently one of the only countries thathas a policy of keeping the countryside as a viableenvironment, as a place where there are newopportunities created’. Various interesting initiatives torevitalize and transition local economics are found inthe Hinterland and the Lonquan International BambooBiennale (Figure 13), curated by local artist GeQiantao and architect George Kunihiro is an excellentexample. An exploration of bamboo and adobe tosupport an ecological lifestyle, through a combinationof a local supplier, an international curator and acombination of functions and architects suited to thecontext. After visiting the finished projects, Lazarova(2017) wrote in the Architectural Review that ‘thesedesigns reappropriate the cultural influences that haveshaped our world, and use this knowledge to bringsomething new to it’[25]. A great example of effectiveeconomic transitioning in the Hinterland.

4.1.3 Sub-topic: Regarding Ecological Integration

Sub-topic: Climate Effects and Ecological Integration

Example Area: The Hebei Floodplains River including areas around Beijing and Xiong’an

Scale: Region

Rationale: As mentioned earlier, if you’re incities you barely notice the severity of the adverseeffects of the climate crisis. But if you’re in thehinterland, as soon as you go out of the city, yourealize the weather is strange and you have to dealwith the real after effects. Weather is becoming moreextreme, and cities are too valuable to sacrifice. Thesurrounding hinterland is sacrificed instead for waterbuffering or flood mitigation. Potentially savingmillions of lives and billions of dollars of GDPproduction in urban centers, but violently uprootingthe daily livelihoods of people living in these lessfortunate hinterlands. In 2023 large areas of Hebeiprovince were intentionally inundated to relievepressure and potential disaster in the urban centers ofthe Tian-Jin-Ji region (figure 14). The usage of bufferareas like this is of course not bound to China, in fact,the Netherlands uses a very similar strategy, but itis vital that this is considered not only from the topdownneeds of the urban clusters, but also from theperspective of the local residents using and inhabitingthese areas Something with which the Netherlandsalready has good experiences.

4.2 Recent Empirical Applications

In this last section a small selection of empiricalapplications in which the author has been personallyinvolvement in related topics over the past few yearswhile simultaneously developing the theoreticalframework.

4.2.1 Rediscovering Ancestral Roads for Sustainable Futures

The ‘Ancestral Roads Joint Research and Design Studio’ exemplifies the empirical applicationof the Hinterland theory by integrating sustainabletourism development with community revitalizationin hinterland regions. This ongoing collaborativeinitiative, co-hosted by Tsinghua University in Beijingand the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru inLima, with researches from ETH Zurich and ETSAMMadrid involved as well, focuses on ancient nonvehiculartrail systems as templates for sustainablefutures. It aims to shows how a particular topic canbe found in various similar conditions in differentHinterland areas around the world, and with a similarstrategy approach that is adjusted to local conditions.The first site of investigation is the renowned IncaTrail System, or Qhapac Ñan, which spans over20,000 kilometers across multiple South Americancountries. The project’s goals extend beyond historicalappreciation to understanding settlement patterns,local conditions, and social structures, forming afoundation for sustainable redevelopment amidstevolving environmental conditions.

The research mission encompasses bothpreserving heritage and envisioning its evolution andadaptation. By conducting in-depth mapping andexploration of the surrounding landscapes, the teamunravels the intricate connections between thesetrails and the social structures that shaped them. Thisunderstanding informs innovative design solutionsthat blend heritage preservation with adaptability,ensuring these historical networks remain relevant inthe face of climate change and shifting landscapes. Asignificant focus is the well-being of the communitieslinked to these landscapes, exploring how low-impacttourism can act as a catalyst for positive change,benefiting both the environment and local populations.The designs aim to balance economic growth with thepreservation of cultural and natural heritage, fosteringcommunity well-being.

While the initial studio focuses on the QhapacÑan, the framework is set within a global context,recognizing the existence of similar systems acrossvarious cultures, both ancient and modern, eventuallyresulting in a comprehensive comparative strategyanalysis. The next phase of the investigation willfocus on China’s Ancient Tea Horse Road, a historictrail that facilitated the trading of tea and other goodswith the help of horses in a similarly mountainousregion, shaping regional economies and fosteringintercultural connections. By studying such pathways,the studio aims to understand their global significanceand explore how they can inspire sustainableredevelopment practices worldwide. This ongoingresearch aims to counter cultural erosion, highlightingthe importance of integrating heritage withsustainability, offering valuable lessons for hinterlandrevitalization globally.

4.2.2 Future Lifestyles in the Hinterland

For this project a group of three students workedunder my guidance on a national student competitionfor a self chosen site and was awarded an honorablemention for their submission. We decided to take onthe topic of county towns, often overlooked, thoughhome to ca 19% of the total Chinese population.Further analysis showed that the population of countytowns is declining, and their development strategiesand supporting facilities are relatively backward.On the other hand, county towns also have theirdevelopment advantages and potential. Compared withbig cities, their pace of life is slower, the pressure islower, and consumption is more affordable. Comparedwith rural areas, they can provide relatively moreintensive and complete life services, such as educationand medical care.

County towns thus provide an excellent topic forthe application of Hinterland strategies, summarizedthrough the special advantages of county townsbetween urban and rural areas. A typical county-leveltown, the hometown of one of the students, in China’sSichuan province was chosen with a specific site todesign an integrated community block, that couldshow the potential for a lifestyle in the hinterland.The design ambition was to combine small scaleagriculture and a complex and diverse population.In the eventual competition submission, the studentsdesigned an interactive, relaxed and high-quality lifeexperience for people from different backgroundsthrough the integration of agricultural facilities andlife and work, so as to create a future community withcounty town characteristics.

This future community was then imagined asa prototype that could suit itself to various similarconditions, in which the future community iscomposed of a series of U-shaped courtyards. Suchcourtyards are highly adaptable and can be modifiedaccording to different sites and needs. Differentresidential unit combinations form buildings in thefour directions of the courtyard: east, west, south, andnorth. Agricultural areas such as fruit trees, rice fields,vegetable plots, and animal husbandry are arrangedinside the courtyard for the common use of residents.These areas not only provide residents with dailynecessities, but also can become a link for residentsto work together and communicate with each other.All together highlighting the ambition for a ‘FutureCommunity Design: with Collective Agriculture as anew lifestyle’ ( figure 15 and 16).

5 Conclusion: Paving the Way for aComprehensive Science of The Hinterland

In conclusion, this paper proposes theestablishment of a Science of The Hinterland,presenting a conceptual framework that defines,understands, and navigates transitional spaces inarchitecture and urban planning. By integratingtheoretical insights with practical applications, itdemonstrates how this Science could be established,relevant, and applicable across various contexts.

Inspired by the Chinese translation forHinterland, 腹地 (fùdì), or ‘abdomen land’, theHinterland framework emphasizes the hidden yetvital nature of these spaces as part of a larger whole.This definition serves as the foundation for a fractaltheory applicable across multiple scales—from globalperspectives, regions, and cities to neighborhoodsand individual buildings. By integrating insightsfrom key architectural and urban planning theoriesand drawing on case studies to illustrate challenges,this paper lays the groundwork for a comprehensiveand adaptable Science of The Hinterland. Embracingthe complexities of transitional zones, this proposedscience seeks to bridge the gap between urban andrural classifications, fostering a more holistic andnuanced approach to contemporary urbanization.

The Hinterland, representing areas that typicallylie behind what is visible or known, provides avaluable framework for addressing the lack of a globaldefinition of urban and rural areas, a core problemhindering international comparisons. By offeringa new paradigm for the interface between urbanand rural spaces, this paper advocates for a deeperunderstanding and appreciation of the Hinterland’spotential. This approach not only addresses thechallenges of contemporary urbanization but alsoopens up possibilities for sustainable and innovativedesign solutions that can enhance the quality of life inboth urban and rural contexts.

In this way, the Science of The Hinterlandpaves the way for a future where the complexitiesand opportunities of transitional spaces are fullyrecognized and harnessed, promoting a balanced andintegrated development approach that benefits diverseenvironments and communities worldwide.