繁荣丽水

摘 要 本文介绍了丽水市举办的“未来山水城:丽水山居”竞赛中,都灵理工大学和华南理工大学为“未来山水城”设计的“繁荣丽水”项目。该竞赛与国家政策相呼应,邀请参赛者根据城市功能和项目与乡村融合,同时也是城市空间与农业融合,提出融合城乡的新愿景。丽水山谷是一个丰富而复杂的生态系统,对农业生产、旅游业以及生态、历史价值保护都很重要,因此被选为标志性地点。“繁荣丽水”项目将现有景观重组为4个系统:①农业生产空间;②山上住宅;③设施和流动的复合系统;④生态保护区。这一设计方案在保护生态多样性的同时,产生了巨大的社会和经济效益。

关键词:空间规划;城市设计;丽水;城乡关系

1 中国腹地的复兴

在过去的20 年中,大多数中国城市的政策和项目逐步将重点从大型城市中心转移到受经济改革影响较小、发展较为缓慢的内部地区,即罗泽尔(Rozelle) 和赫尔(Hell)定义的“隐形中国”[1]。应对这部分中国地区的挑战,意味着要解决农业生产下降、城乡居民收入差距扩大、基础设施和服务缺乏等问题[2-3]。尽管目前农村生活水平有所提高,但国家统计局的数据显示:城市地区的平均收入比农村地区高近3 倍;农村人口中有7% 用不上自来水,2.6%用不上医疗设施,农村地区5 岁以下儿童的死亡率为8%[4]。

为解决这些问题,自 2000 年以来,中国实施了各种措施改善内陆地区的生活条件。其中最重要的是 2006 年提出的“建设社会主义新农村”计划,该计划目前仍在进行中[5]。“建设社会主义新农村”计划的主要目标是改善农村地区的服务和生活水平,保护农田,促进农业生产以满足人们日益增长的需求。与许多其他计划一样,该计划通过对基础设施进行重大投资来实施,从而对农村地区的建筑空间和生产场所进行彻底的重组[6]。这些措施与2014 年出台的《国家新型城镇化规划》和2018 年出台的《乡村振兴战略规划》相呼应,国家为改善农业生产给农村地区分配了大量资源,为解决农村地区治理难题制定了新政策,为提高农村地区生活水平制定了新方案[7-8]。此外,自2019年起,国务院与国家发展改革委(NDRC)建立了部际联席会议制度,以促进这些举措之间的协调,更好地统筹城乡发展[9]。

这些举措得到国家的推动的同时,由地方行政部门和私营企业参与的基层城市化形式也使地方改善农村地区的项目增加。其中,浙江省的试验尤为突出[10-12]。早在2002 年,浙江省政府就启动了“绿色乡村振兴计划”,为农村地区提供服务并提高农业生产。根据这一战略,当地干部实施了具体项目,并取得重要成果。值得一提的是,安吉县政府于2008 年提出保护和更新村庄和传统作物,大力推广以“幸福和健康”为中心的慢旅游。这项名为“美丽乡村”的政策取得了巨大成功,促使浙江省政府在省内其他地区也采取了类似措施。5 年后,国家发起了“美丽中国行动”,将这一乡村战略推广到全国各地[13]。

在这一趋势下,丽水市政府提出了多项倡议,为未来发展制定了新战略。这些举措以空间设计方法为基础,旨在更好地理解如何组织景观和地域,平衡新城市空间的需求和环境资源的保护。本文对此进行了讨论:首先,概述了丽水市的情况,强调了市政府在城市发展方法上的转变,这种转变促进了2020 年“未来山水城”竞赛的推广;其次,介绍了都灵理工大学和华南理工大学(SCUT)的“繁荣丽水”项目;最后,作者希望进一步观察作为重要建筑和城市实验场所的中国腹地。

2 丽水市作为实践基地

丽水市面积17,298km2,人口约270 万[14]。由于其边缘化的状态和复杂的地形,使其成为浙江省最贫困的地区之一:人均 GDP 最低,不到国内发达地区的一半,人均年收入最低,平均为 3 万元人民币[15]。此外,该市居民获得教育和医疗保健的机会很少,向沿海地区的移民率在全省名列前茅[16]。为解决这些问题,过去30 年来,当地政府推动了多项开发该地区的措施。这些措施主要集中在莲都区,该区属于山区,面积超过15 万公顷,居民41.72 万人,其中 18万人居住在丽水市区[14]。

1993 年,浙江省政府设立丽水经济技术开发区 (Lishui ETDZ),2002 年丽水工业园区开始动工,该园区位于丽水市西南4 公里处,占地 14,534 ha。从最初的建设阶段开始,该园区就一直由国家发展改革委监管,并由其提供资金。此后,丽水市于2007 年启动了南城区项目:工业园区东扩,新增一个可容纳17 万居民的新城镇。为实现该项目,3,528 公顷的丘陵地带被平整,并修建了道路,将土地划分为500m×500m 的地块。在这一开发项目中,30%的区域被划分为工业区,25% 的区域被划分为环保设施和公共空间,其余区域被划分为住宅区[17]。2008 年,南城区开始动工,并被列入丽水市城市总体规划(2013—2030 年)。 与此同时,当地政府还建立了莲都—义乌山海合作工业园区,这是一个拥有2 块土地的低碳园区。第一个园区位于丽水市西南 18km处的碧湖镇附近,占地 250 公顷。自2008 年以来,该开发项目已逐步配备基础设施并入驻。第二个园区占地250 公顷,位于丽水市西南17km 处的河谷平原西部的山区边缘。由于这些措施,国务院将丽水经济技术开发区提升为“国家级开发区”,并于 2019 年批准在该新区的南部建设机场[18]。如今,大部分交通基础设施已经完工,工业园区内约一半厂房已完成租赁,而住房、服务设施和工业园区仍在建设中。因此,丽水经济技术开发区拥有4 万居民、1,100 家企业,丽水经济技术开发区占莲都区GDP 的20%[14]。

然而,这种以重工业和城市化为中心的发展模式既对环境造成了影响,也未能阻止农村山区的向外移民和人口减少。此外,许多人对丽水这类小城市能否成功实现其雄心勃勃的城市发展规划表示怀疑。作为回应,国家和省级行政部门目前正在倡导可替代的发展战略,以促进第一产业的发展。这一点对丽水市尤为重要,在过去的20 年中,丽水市的农业收入增长了2 倍多,达155 亿元人民币,占丽水市GDP的7%,农业产业雇用了47.5 万人(每5 个居民中就有一个农民)。在这里,土地开垦一直是这一新战略的核心。在占丽水市农业生产总量20% 的莲都区,农业用地面积翻了一倍多,增加了5,700 公顷[19]。

此外,浙江省政府还颁布了开发环境和文化资源,以及促进旅游业发展的新政策[20-21]。2020 年1 月,浙江省确定了169 个新增长模式实验点[20]。其中,在丽水市莲都区划定了2 个战略区域:①碧湖镇,作为城乡一体化的实验点;②大港头镇,作为具有重要文化和旅游价值的实验点。

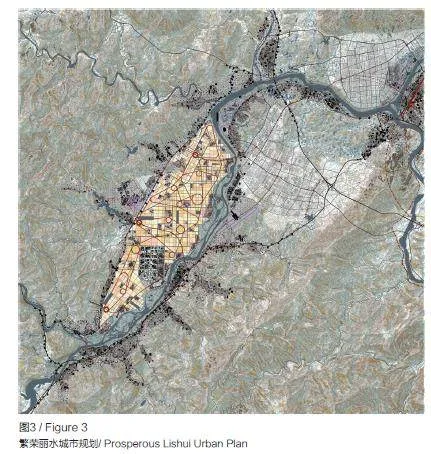

随着丽水城市化战略的转变,市政府启动了2020 年“未来山水城”国际竞赛。规划活动地点位于丽水市西南20km 处的山谷中,竞赛规划面积 152km2(图1,图2)。该区域内居住着 8.5 万人,85% 以上属于农村居民[14]。竞赛设定了4 个主要目标: ①开发新的居住类型,遏制土地消耗,重新补充山区人口;②促进以农业、旅游业和福利为基础的新经济活动;③重组整个区域的服务和设施;④保护和改善当地景观。该竞赛要求参赛者为整个山谷制订空间规划,并设计具体场地。竞赛分两个阶段进行:第一阶段从收到的93 份参赛方案中选出 10 份;第二阶段评出3 个最佳项目。其中包括都灵理工大学和华南理工大学的“繁荣丽水”项目,该项目在第3 节中介绍。

3“繁荣丽水”设计方案

“繁荣丽水”是都灵理工大学和华南理工大学合作完成的规划设计方案,该方案设想将丽水南部的农业谷地建设为新兴大都市发展的绿色新中心。该项目将农业放在首位,打造城市化的农业景观,让新的居住区、设施和高科技农场与传统村落共存(图3,图4)。在这一愿景中,将大部分平整土地保留给农业,而新的开发项目位于山脚下现有的交通基础设施沿线,或者位于山坡上。基于这种方法,该项目设想了4 个主题,以重新定义整个大都市系统的方案、形态和功能:①改善农业生产;②重组交通系统;③根据地形形态定义新的居住系统;④开发新的生态基础设施,首先是重新配置水系统。

3.1 农业生产空间

该场地的农业生产目前占地5,000 多公顷,东面和南面是瓯江,北面是泉溪河,西面是山坡。根据项目设想,这片拥有众多居民点的场地将成为一个强化生产、研究和福利措施的空间,主要通过3 项行动措施来实现:①彻底重组农业用地;②引入室内农业空间;③接入新的城市设施,特别是教育和休闲设施。

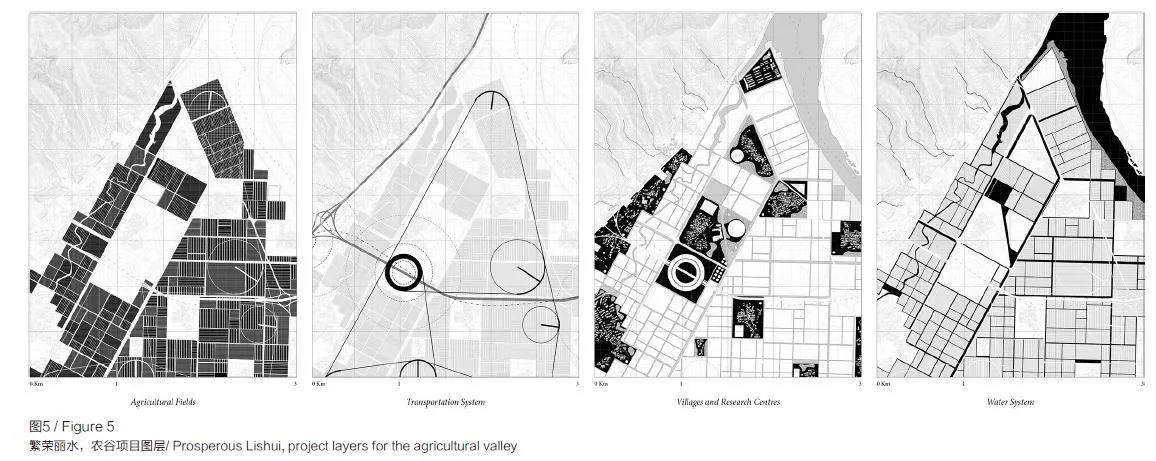

农业用地重组旨在减少对生产效率产生负面影响的过度分散土地。目前,地块面积在0.1 ~ 0.5 公顷之间,大多数由小农业主出让给大公司使用。该项目将这些土地重新安排为5 ~ 12 公顷的地块,共计3,500 公顷。同时,该项目还促进了农作物分化,尤其关注本地的水果和蔬菜种植(图5,图6)。

在进行农业用地重组的同时,改进了农业生产技术。技术先进的农业生产是中国广泛讨论的一个主题,政府机构和高科技公司通过投资自动化设备开发多种形式的智能农业和人工智能农业。鉴于此,该项目建议建造了180 个温室栽培设施,总面积860 公顷,占现有农业用地面积的四分之一,并在现有居住区附近建造150 个垂直农场。除这些农业设施外,还计划建设一个新的高架交通基础设施,用于货物和能源的运输和配送,以连接位于交通要道沿线的3 个物流枢纽。

对农业生产系统的重新思考促进了山谷地区人们生活方式的彻底转变。基于此,项目设想了当前所缺乏的活动空间。具体而言,该项目将提供 21 个休闲活动区(占地12 公顷)、28 个教育活动区(占地55 公顷)、31 个研究实验室和新的医疗保健设施(占地13 公顷)。这些功能的混合,将农业用地变成基础设施、产业和设施丰富的城市化空间。

3.2 山居生活

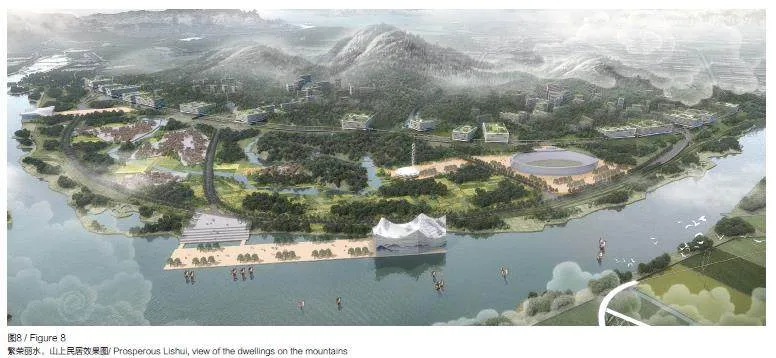

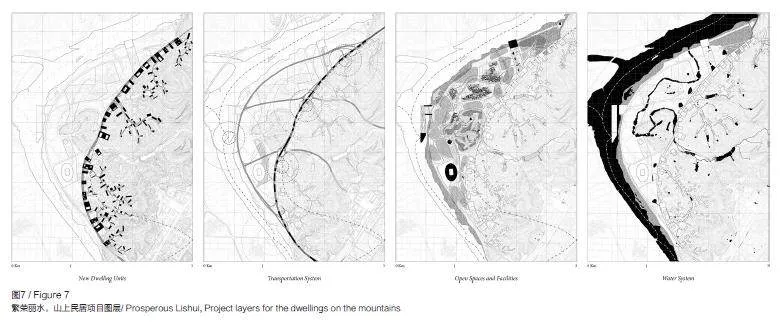

在丽水设想新的居住系统意味着要研究建筑空间与山谷多样景观之间的关系。为此,该项目分别针对山麓地区、平原农业园区、河谷斜坡和高地制定了3 种形式的居住策略(图7,图8)。

为保护平原地区的主要农业活动,新城市发展的主要支点位于山谷边缘。在过去的20 年中,主要的交通基础设施都建在这里,同时还建起了20 层以上的新住宅区和半独立式住宅大院。为顺应这种城市化趋势,该项目提出一个由高密度住宅空间和城市大型设施(公园、体育馆、博物馆、医院)组成的连续居住系统设想。其结果是形成了一个环状结构,与平原地区接壤,并深入较小的山谷中,这是一层城市薄膜,可根据地形因素变宽、变厚或变窄。

就农业园区而言,该项目拟议的住房干预措施主要是恢复现有的村庄,即散布在谷底的43 个紧凑型定居点。这些村庄一般由500 ~ 600 栋2 层或3 层坡屋顶的单户住宅组成,这些住宅是在过去 20 年中用混凝土和砖建成的。该项目要求拆除较小的村落,并对较大的村落进行密集化改造,在现有居住区的边缘增加新的学校、实验室、体育设施、后勤设施、温室和垂直农场等。

最后,居住在山谷的斜坡和高地意味着生活在由森林、小水道和稻田梯田构成的空间中。迄今为止,这些山区的特点是居住区小、人口少,这些居住区由传统的四合院组成,用生土和木头隔开,双坡屋顶上覆盖着瓦片。该项目主张通过保守的行动保护这一遗产,并建造小型建筑来促进文化活动和旅游业的发展。

3.3 设施和交通系统

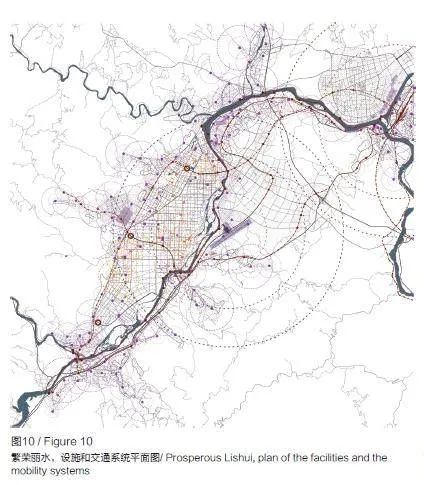

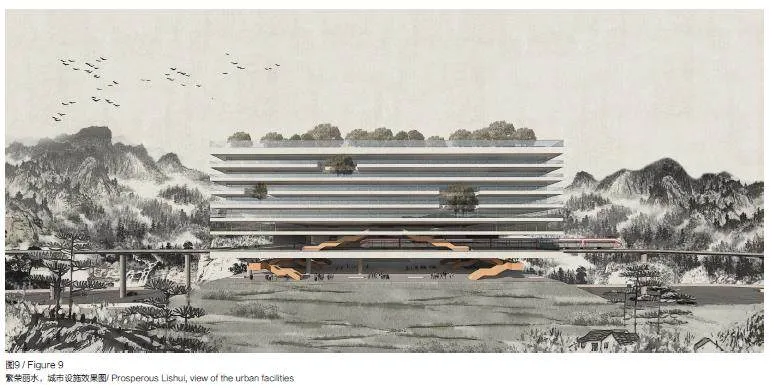

该项目划定了3 个交通系统:①在谷底边缘运行的快速连接系统;②与平原农业园区融为一体的水上交通网络;③连接边谷的广泛小型公路系统( 图9,图10)。

快速交通系统的建设在很大程度上是由地方行政机构推动的,在过去的10 年中,地方行政机构每年新建约200km 的公路。在快速交通系统方面,该项目要求通过建设4 条大都市铁路线和加强现有的南北向公路轴线来升级公共交通系统。该系统是连接现有城区的主要通道,也是未来城市发展的支撑点。

与此相反,通过水上交通系统,在农业谷地推广无车方案,这一系统已在丽水地区的多个区域投入使用。如今,平原农业园区由密集的水泥路组成,只有一条或2 条车道,与新修建的主要道路重叠。该项目计划拆除大部分中等尺寸的道路,恢复约170 公顷的耕地。取而代之的是,设计一个广泛的水渠网络,作为农业定居点与耕地之间的主要连接。

整个交通系统的第3 层是次要连接网络系统,它们从主要道路延伸到横向山谷,并沿着山坡向上延伸。该系统由双车道公路、索道、自行车道和人行道组成,为位于山坡和高地的村庄提供服务,同时也使山谷和山脉,即农业园区和高地森林之间的关系更加紧密。

3.4 生态保护区

丽水山谷属于温带气候,全年雨量充沛,每年4—6 月为降雨高峰期。这种气候与山区地形结合,形成了丰富但脆弱的地貌景观。全境洪水泛滥,水文地质不稳定。为使这样的地貌景观更好地发挥作用,项目建议通过小型水坝和池塘系统来集水,在平原农业园区内修建新的运河,并重新恢复乌江河床的自然状态(图11,图12)。

山地空间以小溪流为特征,最容易受到水文地质不稳定的影响,需要不断维护。近年来,在山谷边缘的各种高地上修建了种植水稻的梯田。按照同样的逻辑,该项目在不适合种植水稻的区域设计了小型水坝用来拦水。此外,该项目还计划加固现有的小型水库,这些水库还可用于水力发电。

然而,平原农业园区也存在水资源管理问题。20 世纪 80 年代中期,在平原农业园区南部修建了3 座大型水库,用于蓄水和水力发电。该项目旨在对这一复杂的水利系统进行改造,使大部分现有运河可以通航,改造方案为:减少小型运河,增加中型运河的容量,恢复历史运河。这就需要建造新的水闸、绿树成荫的码头和养鱼池。

与平原农业园区的工程治水形成鲜明对比的是瓯江治理,瓯江从西南向东北不规则地横穿整个区域。这条水道的河床宽度从 120m 到350m 不等,河岸之间的距离长达1km,河道上有许多小岛,其中一些岛上有人居住。鉴于该区域环境的重要性,该项目推动了河岸加固和恢复自然景观的行动,以保护河谷平原。河岸加固有2 种方式:①在河床变窄的地方,修建“硬河岸”,加固现有的堤坝;②在河床变宽的地方,修建“软河岸”,该区域有助于在涨水期间吸收多余的水,成为保护当地生物多样性的天然绿洲。

4 结 语

“繁荣丽水”项目、中国城市规划设计研究院的“未来超级山水公园”项目和奥利弗·格雷德尔(Olivier Greder)建筑事务所的“共生的城市变化”项目为本次竞赛的3 个获奖项目。尽管这些项目彼此大相径庭,但却有着共同的关注点和目标。最重要的是,需要将丽水市区设想为一个地域公园。据此,“未来超级山水公园”项目利用河流定义该公园的主体结构。奥利弗·格雷德尔的“共生的城市变化”则采用了不同的方法,依靠低密度的城市发展,重新连接山谷的景观、历史结构和文化遗产。其他入围项目也有类似的关注点。博埃里(Boeri )建筑设计咨询公司的“建筑与景观之间的对话”项目旨在通过新的居住区模型,将建筑空间与环境融为一体。同样,UNStudio、Gross Max、Systematica 3 个方案的“城市住房”项目设想在农业乡村的稀有景观中建造紧凑的居住单元。尽管这些方案各不相同[22],但这些方案都将中国腹地诠释为综合用地,要求开发新的混合、多用途空间,据此能够创造出一种包括生产基地、公共空间和服务设施的城市公园。

近年来,这一设计主题,以及解决这一问题的策略成为世界各地许多国际竞赛和公共项目的核心。特别是,这些活动的重点都是由经济的变化和农业技术的进步带来的农村转型、土地和环境的保护,以及优质服务的获取。相比之下,中国目前正在进行的项目走在了城市和建筑实验的前沿。虽然项目实施中与这些设想的偏差仍可能导致与以往城市化进程相同的问题,但目前的发展与以往截然不同:政府要求高质量的项目,世界各地的专业人才都可以引用,建筑技术和材料也在不断改进。因此,在中国工作的城市规划师和建筑师站在了这一进程的前沿,他们的项目不仅与当地的成果相关,还对当代城市规划和设计文化产生了影响。

参考文献

References

[1] ROZELLE S, HELL N. Invisible China: how theurban-rural divide threatens China’s rise[M]. Chicago:University of Chicago Press, 2020.

[2] CHEN M X, ZHOU Y, HUANG X R, et al.The integration of new-type urbanization and ruralrevitalization strategies in China: origin, reality andfuture trends [J]. Land, 2021, 10(2): 207.

[3] HSING Y T. The great urban transformation: politicsof land and property in China[M]. Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press, 2010.

[4] 国家统计局.2022 中国统计年鉴[M]. 北京: 中国统计出版社,2022.

[5] AHLERS A L. Rural policy implementation incontemporary China: new socialist countryside[M].London: Routledge, 2014.

[6] RAMONDETTI L. The enriched field: urbanising thecentral plains of China[M]. Basel: Birkhäuser, 2022.

[7] CHU Y W. China’s new urbanization plan: progressand structural constraints[J]. Cities, 2020, 103: 102736.

[8] LIU Y S, ZANG Y Z, YANG Y Y. China’s ruralrevitalization and development: theory, technology andmanagement[J]. Journal of Geographical Sciences, 2020,30(12): 1923-1942.

[9] HAN J. Prioritizing agricultural, rural developmentand implementing the rural revitalization strategy[J]. ChinaAgricultural Economic Review, 2019, 12(1): 14-19.

[10] FEIREISS K, COMMERELL H J. The Songyangstory: architectural acupuncture as driver for socio-economicprogress in rural China[M]. Zürich: Park Books, 2021.

[11] LIN X Y, JIA B S. Multi-level housing governance inrural settlement: transformation of two vernacular housesin Zhejiang Province of China[J]. Journal of ChineseArchitecture and Urbanism, 2023, 4(2): 174.

[12] SUN N, LUO D Y, TANG W. From plan to practice:the revival of Pingtian village in Songyang countyof Zhejiang province in China[J]. Journal of ChineseArchitecture and Urbanism, 2022, 4(2): 177.

[13] WELLER R J, HANDS T L. Beautiful China:reflections on landscape architecture in contemporaryChina[M]. Los Angeles: Oro Editions, 2020.

[14] 丽水市统计局, 国家统计局丽水调查队. 2022 丽水统计年鉴[M]. 北京: 中国统计出版社, 2022.

[15] YUE W Z, ZHANG Y T, YE X Y, et al. Dynamicsof multi-scale intra-provincial regional inequality inZhejiang, China[J]. Sustainability, 2014, 6(9): 5763-5784.

[16] 浙江省统计局, 国家统计局浙江调查总队.2022浙江统计年鉴[M]. 北京: 中国统计出版社,2022.

[17] 浙江省住房和城乡建设厅.2020 年度美丽城镇建设样板创建名单公布[EB/OL].(2020-01-10)[2024-02-01].http://jst.zj.gov.cn/art/2020/1/10/art_1569971_41573668.html.

[18] 丽水市发展和改革委员会.《丽水机场总体规划》通过专家评审[EB/OL].(2019-04-25)[2024-02-01].http://fgw.lishui.gov.cn/art/2019/4/25/art_1229228842_58699765.html.

[19] LI Y, WU H X, SHI Z. Farmland productivity and itsapplication in spatial zoning of agricultural production: acase study in Zhejiang province, China[J]. EnvironmentalEarth Sciences, 2016, 75(2): 159.

[20] 中国共产党浙江省委员会, 浙江省人民政府. 中共浙江省委、浙江省人民政府关于推进文化浙江建设的意见[EB/OL].(2018-03-22)[2024-02-01].http://www.law-lib.com/law/law_view1.asp?id=613911.

[21] 浙江省文化和旅游厅. 图解《浙江省全域旅游发展规划(2018-2022)》[EB/OL].(2018-12-13)[2024-02-01].http://ct.zj.gov.cn/art/2018/12/13/art_1652999_34933757.html.

[22] RAMONDETTI L. Envisioning rural futures: Lishuiand the Future Shan-Shui City competition[J]. Journal ofChinese Architecture and Urbanism, 2023, 5(3): 0957.

ORIGINAL TEXTS IN ENGLISH

Prosperous Lishui:A Project for Chinese Hinterland

Leonardo Ramondetti, Camilla Forina

1 The Remaking of Chinese Hinterland

Over the last two decades, most Chinese urbanpolicies and projects have progressively shifted theirfocus from large urban centres towards what Rozelle and Hell defined as “the invisible China”: internalareas only slightly impacted by the developmentthat came after the economic reform[1]. Addressingthe challenges of this part of the Chinese territory,means dealing with the fall in agricultural production,the widening income gap between urban and ruralpopulations, and the lack of infrastructures andservices[2-3]. Despite improvements in rural standardsof living, data from the National Bureau of Statisticsshow that the average income in rural areas is nearlythree times lower than that of urban areas; 7% of therural population has no access to running water, 2.6%has no access to hospital facilities, and the mortalityrate of children under five in rural areas is 8%[4].

To address these issues, various initiativeshave been implemented since the 2000s to improveliving conditions in the Chinese hinterland. Themost significant was the Building a New SocialistCountryside program, introduced in 2006 and stillongoing[5]. The program’s main objectives are toimprove services and living standards in rural areas,to preserve farmland, and to boost agriculturalproduction to meet the growing demand. This program,like many others, has been implemented throughmajor infrastructural investments, leading to a radicalreorganization of constructed spaces and productivesites in rural areas[6]. In continuity with these initiatives,the National New Type of Urbanization Plan and theRural Revitalization Strategy Plan were launched in2014 and 2018 respectively, with massive resourcesallocated for improving agricultural production, newpolicies to address governance difficulties, and novelprograms for improving the living standards in ruralareas[7-8]. Furthermore, since 2019, the State Councilhas established an inter-ministerial joint conferencesystem with the National Development and ReformCommission (NDRC) to foster the coordinationbetween these many initiatives and better integrateurban-rural development[9].

While these initiatives have been promotedby the national government, forms of grassrootsurbanization involving local administrationsand private players have led to a rise in localprojects to improve rural areas. In particular, theZhejiang Province has been a place of exceptionalexperimentation [10-12]. Already in 2002, the ProvincialGovernment launched the Green Rural Revivalprogram to supply services in rural areas and toimprove agricultural production. Following thisstrategy, local cadres implemented specific projects that resulted in important achievements. Particularlynoteworthy is the government of Anji County, whichin 2008 enacted policies for the preservation andrenewal of villages and traditional crops, stronglypromoting slow tourism centred on well-beingand health. This initiative, known as BeautifulCountryside, had a great success, prompting theregional government to adopt similar measures acrossother parts of Zhejiang. Five years later, the nationalgovernment launched the Beautiful China Initiative,extending this rural strategy nationwide [13].

Following this trend, municipalities like Lishuihave promoted several initiatives to envision newstrategies for future development. These are based ona spatial design approach to better understand howto organise landscapes and territories, balancing theneed for new urban spaces with the preservation ofenvironmental resources. This article discusses thisas follows: first, an overview of the Lishui Valley isprovided, highlighting the shift in urban approachadopted by the Municipality which led to thepromotion of the Future Shan-Shui City competitionin 2020; after this, the article presents the projectProsperous Lishui by Politecnico di Torino and SouthChina University of Technology (SCUT); finally, the final remarks invites a further observation of Chinesehinterlands as a place of significant architectural andurban experimentation.

2 Lishui Valley as a site for Experimentation

The Lishui Municipality extends over 17,298square kilometres and has a population of about 2.7million people[14]. Due to its marginal status and adifficult orography, it is one of the poorest areas in theZhejiang Province: it has the lowest per-capita GDP,less than half that of the more developed areas, andthe lowest annual per-capita income, an average of30,000 CNY[15]. Furthermore, access to education andhealthcare is poor, and the migration rate toward thecoastal regions is among the highest in the province[16].To address these issues, the local government haspromoted numerous initiatives to develop the areaover the last 30 years. These efforts have focused onthe Liandu District: a mountainous territory coveringover 150,000 hectares, with 417,200 inhabitants, ofwhom 180,000 live in Lishui city [14].

In 1993, the provincial government ofZhejiang instituted the Lishui Economic TechnologyDevelopment Zone (Lishui ETDZ), and in 2002work began on the Lishui Shuige Industrial Park: a14,534-hectare development located four kilometressouthwest of Lishui city. Since the initial twoyearconstruction phase, the site has been under thesupervision of the National Development and ReformCommission, which has funded its realization.Thereafter, in 2007, Lishui Municipality promotedthe Nancheng District: an eastward expansion ofthe industrial park with the addition of a new townfor 170,000 inhabitants. To realize the project, ahilly territory of 3,528 hectares was levelled andequipped with roads parcelling out plots of 500x500meters. Within this development, 30% of the areawas designated for industry, 25% for environmentalfacilities and public spaces, and the remainder forresidential use [17]. Work began the following year,and Nancheng District was included in the UrbanMasterplan of Lishui City (2013-2030). In parallel,the local administration established the Liandu-YiwuShanghai Cooperation Industrial Park, a low-carbondistrict on two sites. The first covers 250 hectaresnear Bihu Town, 18 kilometres southwest of Lishuicity. Since 2008, this development has been graduallyequipped with infrastructures and inhabited. Thesecond site covers 250 hectares along the mountainouswestern edge of the valley plain, 17 kilometressouthwest of Lishui city. Thanks to these initiatives,the State Council raised Lishui ETDZ to the statusof “area of national interest”, and in 2019 approvalarrived for the construction of an airport south of thenew district [18]. Today, most mobility infrastructureshave been completed, about half of the industrial areahas been leased, while housing, services and parks arestill under construction. As a result, Lishui ETDZ has40,000 inhabitants, 1,100 companies, and accounts for20% of the GDP of Liandu District [14].

However, this development model, centredon heavy industry and urbanization, has impactedthe environment, and failed to stem migration anddepopulation in rural mountainous areas. Additionally,many doubts have been voiced regarding the abilityof minor municipalities like Lishui to effectively fulfiltheir ambitious plans for urban growth. In response,national and provincial administrations are nowadvocating for alternative developmental strategies to boost the primary sector. This is particularly relevantfor Lishui Municipality, where agriculture represents7% of the GDP and employs 475,000 people (one infive residents), with revenues having more than tripledto 15.5 billion CNY over the last two decades. Here,land reclamation has been at the heart of this newstrategy. In Liandu District, which accounts for 20%of the Lishui Municipality’s agricultural production,the agricultural land area has more than doubled,increasing by 5,700 hectares [19].

F u r t h e r m o r e , n e w p o l i c i e s t o d e v e l o penvironmental and cultural resources, and to promotetourism have been enacted [20-21]. In January 2020,the Zhejiang Province identified 169 experimentalsites for new growth models [20]). Among these,two strategic areas have been designated in LianduDistrict: Bihu Town, as an experimental site for urbanruralintegration; and Dagangtou Town, as a place ofgreat cultural and tourism value.

In line with the shift in Lishui urbanizationstrategy, the municipality launched the internationalcompetition Future Shan-Shui City in 2020. The sitefor the planning activities is a 152-square-kilometresarea cantered on a valley 20 kilometres southwest ofLishui (Figures 1-2). 85,000 people inhabit this space,more than 85% of residents are classified as ruralcitizens [14]. The competition set four main objectives:1) developing new typologies of settlement to curbland consumption and repopulate the mountainousareas; 2) promoting new economic activities based onagriculture, tourism, and wellbeing; 3) reorganisingservices and facilities throughout the site; 4) preservingand enhancing the local landscape. Participants wereasked to develop a spatial plan for the entire valley anddesign specific sites. The competition was organized intwo phases: the first phase selected 10 proposals fromthe 93 entries received, and the second awarded thethree best projects. Among these is Prosperous Lishuiby Politecnico di Torino and SCUT, which is presentedin the next section.

3 Prosperous Lishui

Prosperous Lishui envisions the agrarianvalley south of Lishui as the new green centreof the emerging metropolitan development. Theproject prioritizes farming to produce an urbanizedagricultural landscape where new settlements andfacilities coexist with high-tech farms and traditionalvillages (Figures 3-4). In this vision, most of theflatland is reserved for agriculture, while newdevelopments are situated either along the existingmobility infrastructures at the foot of the mountains,or on the slopes. Based on this approach, theproject develops four themes to redefine programs,morphologies, and functions of the whole metropolitansystem: 1) improving agricultural production; 2)reorganising the mobility system; 3) defining newsettlement systems based on the terrain’s morphology;4) developing new ecological infrastructures, startingwith the reconfiguration of the water system.

3.1 Spaces for Agricultural Production

Agricultural production in Lishui Valleycurrently covers over 5,000 hectares bordered bythe Ou River to the east and south, the Quanxi Riverto the north, and the mountain slopes to the west.In the project hypothesis, this area with numeroussettlements becomes a space that intensifies measuresfor production, research, and welfare, through three main actions: the complete reorganizationof agricultural lands; the introduction of spacesfor indoor farming; and the grafting of new urbanfacilities, especially for education and leisure.

The land reorganization aims at reducing theexcessive fragmentation of the territory, whichnegatively impact production efficiency. At present,the parcels range between 0.1 and 0.5 hectares, andare mostly ceded by small agricultural owners to largecompanies for use. The project rearranges the landinto lots ranging from 5 to 12 hectares, totalling 3,500hectares of arable land. In parallel, the project fosterscrop differentiation, paying particular attention tonative fruits and vegetables (Figures 5-6).

This reorganization is accompanied bythe improvement of production technologies.Technologically advanced agricultural production isa theme widely discussed in China, with governmentagencies and high-tech firms investing in thedevelopment of many forms of smart agriculture andAI farming via automated equipment. Consideringthis, the project proposes the creation of 180 structuresfor greenhouse cultivation, covering a quarter of theavailable area (860 hectares), and 150 vertical farmslocated close to existing settlements. Alongside thesenew facilities, a new elevated infrastructure for themovement and distribution of goods and energy isplanned to connect three logistical hubs sited alongthe main road for transportation.

The rethinking of the agricultural productionsystem leads to a radical transformation of the way ofliving the valley. For this reason, the project envisionsspaces for activities currently missing. Specifically, 21areas for recreational activities (12 hectares), 28 foreducational activities (55 hectares), and 31 researchlaboratories and new healthcare facilities (13 hectares)are provided. These mix of multiple activities turnsthe farming sites into urbanized spaces rich ininfrastructure, industries, and facilities.

3.2 Dwelling on the Mountains

Envisioning new settlement systems in Lishuimeans to investigate the relationship betweenconstructed space and the diverse landscape of thevalley. In this respect, the project develops three formsof housing strategy in relation to the piedmont areas,the agricultural park of the plain, and the valley slopesand highlands respectively (Figures 7-8).

To preserve the plains mainly for agriculturalactivities, the main fulcrum of new urban developmentis sited at the edges of the valley. Here, over the lasttwo decades the major mobility infrastructures havebeen built together with new housing complexeswith twenty-or-more-story buildings and compoundsof semi-detached houses. The project counters thisurbanization by proposing a continuous settlementsystem composed of high-density residential spacesand urban macro-facilities (parks, stadiums, museums,hospitals). The result is a sort of ring that bordersthe plain and probes into the smaller valleys: anurban membrane that widens, thickens, or narrowsdepending on the topographical factors.

For the agricultural park, the proposed housinginterventions primarily regard the recovery of existingvillages, i.e., 43 compact settlements scattered at thebottom of the valley. These villages generally consist of500-600 single-family houses with two or three floorsand pitched roofs, built in concrete and brick over thelast 20 years. The project calls for the removal of the smaller villages and a densification of the larger ones,working on the margins of the existing settlementsby adding new schools, laboratories, sports facilities,logistical features, greenhouses, and vertical farms.

Finally, inhabiting the slopes and highlands ofthe valley means living in a space made of forests,small waterways, and terraces for the rice fields. Todate, these mountainous areas have been characterizedby small settlements and shrinking population. Thesesettlements are made up of traditional courtyardhouses, with partitions in raw earth and wood, anddouble-pitched roofs covered with tiles. The projectadvocates for the preservation of this heritage throughconservative actions, and the construction of smallarchitectures to promote cultural activities and tourism.

3.3 Facilities and System of Mobility

The project delineates three systems of mobility:1) a rapid connection system running on the marginsof the valley floor; 2) a water mobility network,integrated in the agricultural plain; 3) a widespreadsystem of smaller road connecting the side valleys(Figures 9-10).

T h e c o n s t r u c t i o n o f s y s t e m s f o r r a p i dtransport mobility has been largely promoted bylocal administrative bodies, which have built about200 kilometres of new highways per year overthe last decade. In this respect, the project solicitsthe upgrading of public transport by creating fourmetropolitan railway lines and reinforcing the existingnorth-south road axes. This system serves as the mainconnection between the existing urban settlements andas a support for future urban development.

Conversely, a no-car scenario is promoted inthe agricultural valley with the adoption of watertransport, a system already in use in several areas ofthe Lishui prefecture. Today, the agricultural plainis composed of a dense pattern of concrete roads,with one or two lanes, overlaid by major recentlyconstructed roads. The project envisions removingmost of the medium-size roads roads, recoveringabout 170 hectares of land for cultivation. Instead,a widespread network of water canals is designedto be the primary connection between agriculturalsettlements and cultivations.

Finally, the third layer of the overall mobilitysystem is the network of minor connections. Theseextend from the major roads into the lateral valleysand run up the slopes. This system, composed of twolaneroads, cableways, bicycle paths, and pedestrianwalkways serves the villages located on the slopesand the highlands, also permitting close relationsbetween the valley and the mountains, i.e., betweenthe agricultural park and the highlands’ forests.

3.4 Ecological Reserve

The valley of Lishui has a temperate climatewith abundant rainfall throughout the year, with peaksfrom April to June. This climate, combined with themountain topography, generates a rich but fragilelandscape. The whole territory is subject to floodingand hydro-geological instability. To ensure the betterfunctioning of such a landscape, the project proposesconsolidating the slopes through a system of smalldams and ponds to collect water, constructing newcanals inside the agricultural plain, and re-naturalizingthe Ou riverbed (Figures 11-12).

The mountainous space, characterized by smallstreams and brooks, is the most vulnerable to hydrogeologicalinstability, requiring constant maintenance.In recent years, terraces for growing rice have beenbuilt on various highlands at the valley’s edges.Following the same logic, the project designs smalldams to contain water in areas unsuitable for ricefields. Additionally, it invites to reinforce the existingsmall water reservoirs, which can also be used forhydroelectric energy production.

However, water management issues arise alsoin the agricultural plain. Here, there has been aprogressive land engineering, culminating in the mid-1980s when three large reservoirs were built to thesouth of the plain to contain the water and contribute tohydroelectric energy production. The project sets out towork on this complex hydraulic system to make a largepart of the existing canals navigable: reducing the smallcanals, increasing the capacity of medium ones, andrestoring historical ones. This entails the construction ofnew locks, tree-lined quays, and fish farming pools.

The engineering water management of theagricultural plain is contrasted by the Ou River, whichirregularly crosses the landscape from southwest tonortheast. This waterway has a bed varying in sizefrom 120 to 350 meters, with distances between thebanks extending up to one kilometre, with large islands,some of which are inhabited. Given the environmentalimportance of this area, the project promotes operationsof consolidation and re-naturalization of the riverbanksin order to protect the plain of the valley. Theconsolidation occurs in two ways. Where the riverbednarrows, the creation of “hard banks” is proposed,reinforcing the existing embankments. Vice versa,where the riverbed widens the project develops “softbanks”: damp areas that contribute to absorb excesswater during periods of high water, serving as naturaloases to preserve the local biodiversity.

4 Concluding Remarks

The Prosperous Lishui project is one of thethree winners of the competition alongside FutureSuper Shan-shui Park by the China Academy ofUrban Planning and Design, and A Symbiotic UrbanChange by Olivier Greder Architects. Though verydifferent from each other, these projects stem fromshared concerns and set common objectives. Aboveall, the need to envision Lishui’s metropolitan area asa territorial park. In line with this, the project FutureSuper Shan-shui Park uses the rivers to define themain structure of this park. With a different approach,A Symbiotic Urban Change by Oliver Greder relieson low-density urban development to reconnect thelandscape, historical fabric, and cultural heritage ofthe Valley. Similar attention is also in other finalistprojects. Dialog Between Architecture and Landscapeby Boeri Architecture Design Consulting aims tointegrate constructed spaces and the environmentthrough new settlement prototypes. Similarly, UrbanRooms project by UNStudio, Gross Max, andSystematica envisions the construction of compactsettlement units inserted in the rarified landscape ofthe agricultural countryside. Even though diversefrom one another[22], all these scenarios interpretChinese hinterlands as composite sites, soliciting thedevelopment of new hybrid, mixed-use spaces capableof creating a sort of city-park including productionsites, public spaces, and services.

This design theme, and the strategies to addressit, have also been at the core of many internationalcompetitions and public programmes all over the worldin recent years. Particularly, these initiatives focus onthe transformation of the countryside due to changes inthe economy and advancements in farming techniques,the preservation of land and environment, and accessto high-quality services. In comparison, the projectscurrently underway in China seem to be at the forefrontof urban and architectural experimentation. Whiledivergences from the vision of these scenarios couldstill lead to the same problems that have characterisedprevious urbanization, current development appearsradically different: administrations demand high-qualityprojects, expertise from all over the world is available,and construction techniques and materials haveconsistently improved. Consequently, urban plannersand architects working in China are at the vanguard ofthis process, and their projects are relevant not solelyfor their local outcomes, but also for their impact on thecontemporary culture of urban planning and design.