Advances in joint roughness coefficient (JRC) and its engineering applications

Nik Brton,Chngshuo Wng,Rui Yong

a Nick Barton &Associates,Fjordveien 65c,Høvik,Oslo,1363,Norway

b School of Civil Engineering,Shijiazhuang Tiedao University,Shijiazhuang,050043,China

c Rock Mechanics Institute,Ningbo University,Ningbo,315211,China

Keywords:Joint roughness coefficient (JRC)Rock joints Roughness Shear strength Scale effect

ABSTRACT The joint roughness coefficient (JRC),introduced in Barton (1973) represented a new method in rock mechanics and rock engineering to deal with problems related to joint roughness and shear strength estimation.It has the advantages of its simple form,easy estimation,and explicit consideration of scale effects,which make it the most widely accepted parameter for roughness quantification since it was proposed.As a result, JRC has attracted the attention of many scholars who have developed JRC-related methods in many areas,such as geological engineering,multidisciplinary geosciences,mining mineral processing,civil engineering,environmental engineering,and water resources.Because of such a developing trend,an overview of JRC is presented here to provide a clear perspective on the concepts,methods,applications,and trends related to its extensions.This review mainly introduces the origin and connotation of JRC, JRC-related roughness measurement, JRC estimation methods, JRC-based roughness characteristics investigation, JRC-based rock joint property description, JRC’s influence on rock mass properties,and JRC-based rock engineering applications.Moreover,the representativeness of the joint samples and the determination of the sampling interval for rock joint roughness measurements are discussed.In the future,the existing JRC-related methods will likely be further improved and extended in rock engineering.

1.Introduction

Rock joints,mechanical discontinuities of geological origin,intersect almost all near-surface rock masses and significantly influence their engineering properties.Roughness is an essential component of the shear strength of rock joints,particularly in the case of undisplaced and interlocked features such as unfilled joints.This is because lack of planarity means dilation,higher local stresses,and increased permeability.Over the past five decades,researchers have proposed different methods to quantify the joint roughness(e.g.Barton and Choubey,1977;Yu and Vayssade,1991;Kulatilake et al.,2006;Tatone and Grasselli,2010;Yong et al.,2017).Among all the joint roughness parameters in the literature,the joint roughness coefficient(JRC)is the one most widely used in practice.It was first proposed by Barton(1973) some 50 years ago for evaluating rock joint shear strength and quantifying roughness.JRCwas later adopted by the International Society for Rock Mechanics(ISRM) (Barton,1978) for the description of discontinuities.It has the advantages of simple form,easy estimation,and explicit consideration of scale effects.Since the quantification ofJRCis crucial to the shear strength of jointed rock masses,it has attracted a large number of attentions.

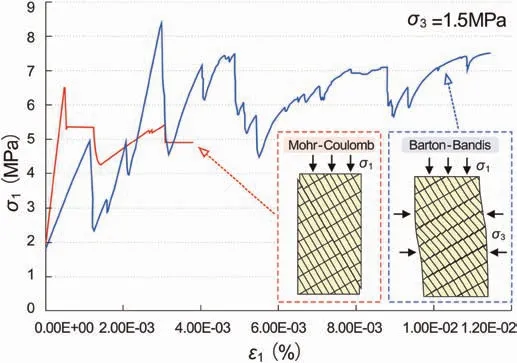

JRC-related methods have gradually developed as general methods for solving rock engineering stability problems.The concept ofJRChas been applied in various fields such as geological engineering,multidisciplinary geosciences,mining mineral processing,civil engineering,environmental engineering,and water resources.In theseJRC-related methods,the nonlinear rock joint shear strength criterion,called Barton-Bandis criterion(also called BB criterion),is the most used.This criterion,with the shear strength portion refined by Barton and Choubey (1977),received important additions from the scale-effects and normal-closure work of Bandis (1980).Since the 1980s,this criterion has been used in numerous computer codes for mechanical-hydraulic coupled modeling(e.g.UDEC-BB since 1985)because it is nonlinear and more accurate than the traditional Mohr-Coulomb linear method.

Since the introduction of theJRCconcept in 1973,many researchers have sought to find better methods of objectively and accurately estimatingJRC.Many innovative,impartial,and practical methods were proposed for joint roughness characterization.In these methods,Barton and Choubey(1977)were the first to apply the tilt test(or self-weight gravity shear test)method in a‘scientific’way to determineJRC.Some researchers have misunderstood and thought thatJRCis a subjective parameter that only reflects twodimensional (2D) roughness and not three-dimensional (3D)roughness.Obviously,the tilt test reflects the “real” 3D shear behavior of rock joints,thusJRCrecorded in this way is 3D.In addition,the shearing direction is also taken into consideration in the tilt test;thus,theJRCrecords the directional roughness.The authors are aware of numerous different equations for assessingJRC(e.g.Tse and Cruden,1979;Yu and Vayssade,1991;Tatone and Grasselli,2010;Kulatilake et al.,2006;and many others).However,the great majority are rather complex descriptions of a topological nature or linked to 3D laser profilometric analysis.For engineering application purposes,the joint roughness characterization method must be quantitative and meaningful,and the cost must remain within acceptable limits.Additionally,when using mathematical descriptions of digitized joint topology,surface weathering (or prior shear) should not interfere with such surface exposure analysis.

This paper consists of the following parts.The next section 2 introduces the origin and early application ofJRC.Section 3 reviews the roughness measurement ofJRC.Section 4 introduces the methods forJRCestimation.The investigations of anisotropy and scale effect of joint roughness are given in Section 5.In Section 6,we conclude the descriptions of the properties of rock joints based onJRC.Section 7 summarizes the influences ofJRCon the properties of rock masses.Section 8 introduces the engineering applications.Finally,the discussion and conclusions are drawn in Sections 9 and 10,respectively.

2.Origin and connotation of JRC

The main purpose of joint roughness quantification is to facilitate the estimation of shear strength,especially for unfilled joints where estimates may be quite accurate.

The following equation related to granular materials was proposed by Newland and Allely (1957) to describe and estimate the shear resistance of sands and granular soils:

where τ denotes the maximum shear strength,σnis the effective normal stress,φbdenotes the angle of frictional sliding resistance between particles,andiis the average angle of deviation of particle displacements from the direction of the applied shear stress.

Patton(1966)observed that the shear strength of irregular joint surfaces could also be represented by Eq.(1) under low normal stresses.However,the Coulomb linear relation was assumed to be satisfied under high normal stresses because most irregularities were expected to be sheared off.Thus,the following bilinear envelope equation was proposed for describing the shear resistance under both high normal stresses and low normal stresses:

wherecandφare the Coulomb parameters,i.e.the cohesion and friction angle,respectively.

Patton(1966) found that the“first-order”irregularities provide the predominant contributions to the shear strength of major joint surfaces under natural slopes (Fig.1a) because “second-order” irregularities usually fail due to slope creep and weathering.Notably,all scales of the roughness of rock joints below the surfaceweathered zone are probably significant.Fig.1b depicts an idealized,smooth,inclined joint surface.Sliding is initiated when the resultant force is inclined at an angleφb(basic friction angle)from the normal to the inclined surface.Therefore,the tangent of the“total friction angle” is equal to the ratio of the horizontal force to the normal force acting on the rock joint.However,the surface of a natural joint often has a wide variety of asperities with variousivalues(Fig.1c).If this hypothetical sample in Fig.1c is extracted for shear testing,then the ratio ofHandNcan be expressed as follows:

Fig.1.(a)The effective i value for a natural slope under different orders of irregularities(after Patton,1966);and the angular components of shear strength for(b)a planar joint and(c) a non-planar joint (after Barton,1973).

wheredndenotes the peak dilation angle equal to the instantaneous inclination of the shearing path at peak strength relative to the mean plane.This component represents the minimum energy path between a“sliding-up”and a“shearing through”failure mode.snis the shear component that represents the failure of surface asperities.

Barton(1971,1973)originally developed a method of estimating the shear strength of ‘fractures’ based on experimental observations of the behavior of rough artificial tension fractures which were developed through realistic brittle model materials.The unconfined compressive strengths (σc) of the tested samples ranged between 0.072 MPa and 0.84 MPa.Barton (1971) obtained the following empirical equations based on the relationship betweendnand tan-1(τ/σn) and the relationship betweendnandσc/σn:

The criterion of peak shear strength for rough-undulating and unweathered joints could therefore be written as follows:

The values ofφbfor the model materials varied from 28.5°to 31.5°;thus,the value of 30°in Eq.(6) can be viewed as an approximation toφb.As joint samples are normally unweathered in their original in situ condition,σcin Eq.(6) will yield an upper bound estimate of τ.Following this early work with artificial tension fractures,the effective joint wall compressive strength (JCS)was proposed (Barton,1973) for generalizing both weathered and unweathered joints.If the joints are completely unweathered,JCSwill equal the unconfined compressive strength of the unweathered rock (σc).In general,rock joint walls are weathered to some extent,and theJCSwill be lower thanσc.

Since the shear strength measured along individual joints strongly depends on the joint roughness.Eq.(6)can be modified to incorporate different degrees of surface roughness.

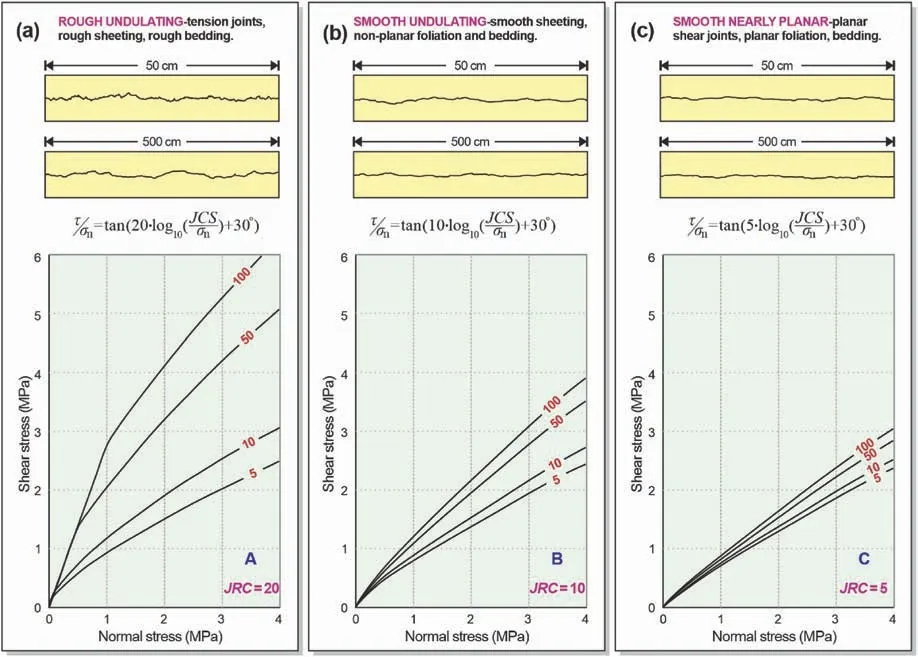

To investigate the influence of surface roughness on shear strength,the three estimates shown in Fig.2 were preliminary efforts to improve the classification and description of non-planar joints (JRC=20,10 and 5 for classes A,B and C,respectively).

Fig.2.Empirical law for prediction of shear strength of non-planar joints(after Barton,1973).(a),(b)and(c)show the roughness profiles as an approximate guide to the appropriate JRC values 20,10 and 5.

Later,Barton (1973) found that the peak friction angle can be quantitatively represented byJRC,JCSandφb,and the peak shear strength can be expressed in a generalized form based on laboratory tests of 130 natural joint samples (Fig.3).The generalized form of Eq.(6)was given as follows (Barton,1973):

Fig.3.Peak shear strength and the statistical result of JRC,JCS and φr for 130 natural joint samples based on laboratory tests at 100 mm scale (after Barton and Choubey,1977).

The ‘i-value’ in Eq.(2) can therefore be replaced by a stressdependent logarithmic function incorporating variable (and scaledependent) roughness.JRCwas later defined as a sliding scale of roughness ranging from approximately 20 to 0 from the roughest to the smoothest end of the spectrum.It is a dimensionless number,approximately equivalent to the ratio of roughness amplitude and sample length (with a multiplier of approximately 400).It is important to note that the parameterJRCdescribes the relative roughness of rock joint walls which havecorrelatedroughness,i.e.there is a considerable degree of potential interlock when the joint is‘closed’by increased normal stress.TheJRCcan be determined by rearrangement of Eq.(7) as follows:

The suggested parameters,JRC,JCSandφb,were soon expanded to include the residual friction angleφrfor weathered joints(Barton and Choubey,1977).The improved empirical model of peak shear strength and the corresponding form ofJRCfor the general case of weathered and unweathered joints is given as follows:

JCScan be estimated using the point load test (if the joint wall can be sampled) or the Schmidt hammer index test (Broch and Franklin,1972;Barton and Choubey,1977).The parameterφbin fact reflects the mineralogical properties of planar rock surfaces.Thus,measuringφbrequires smooth and unweathered rock surfaces,such as saw cuts or core,both without ridges.Although steep micro-asperities may be displayed on planar rock surfaces under microscopic examination,the planar surfaces should have no obvious roughness component on a visible scale.Therefore,the value ofφbcan be obtained from residual shearing tests on planar rough-sawn or sand-blasted rock surfaces.Generally,the value ofφbcan be estimated from the recommended values for various rock types and moisture conditions reviewed from an extensive literature by Barton and Choubey(1977).Additionally,the value ofφrcan be estimated based on the ratio between the Schmidt hammer reboundrobtained on a saturated weathered joint wall and the reboundRobtained on an unweathered dry rock surface as follows:

Since theJCSandφb(orφr) values can be estimated quite accurately,the real unknown is theJRC.Detailed information regardingJRCestimation methods is discussed in Section 4,and some properties of joint roughness investigations based onJRCare discussed in Section 5.

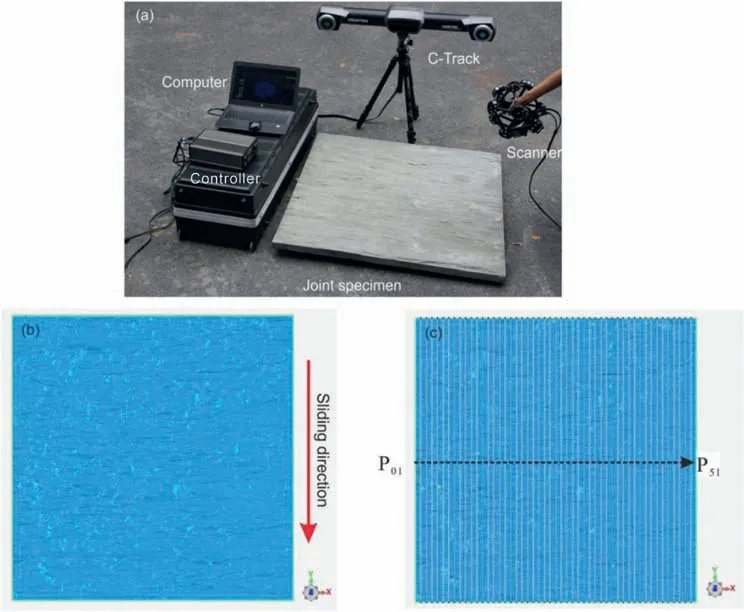

3.Roughness measurement for JRC

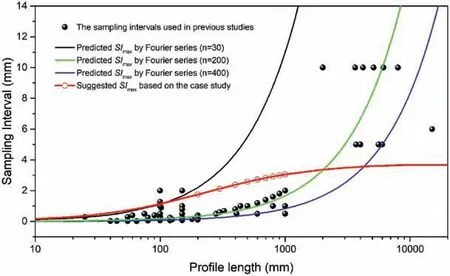

In general,JRCcan be obtained based on two options:roughness measurement-based estimation and actual testing techniques(the details are given in Section 4).Accurate measurement of the roughness of the rock joint surface may be drill-core based or utilizing unweathered exposures if these are available.This section presents some commonly used instruments and methods to measure joint roughness in situ and in the laboratory.It is noticed that joint roughness measurement continues to gain attention as highperformance computing and non-contact measurement techniques become more widespread.These methods (e.g.photogrammetry,image processing,structured-light scanning,and laser scanning)provide good solutions for roughness measurement-basedJRCestimation.Photogrammetry refers to the process of measuring 3D information from two or more 2D images of the same scene taken from different standpoints (Buzzi and Casagrande,2018;Bahaaddini et al.,2022).The image processing method for roughness measurement is the image recognition technology to quantify surface roughness.But unlike photogrammetry,it does not need to obtain the 3D topography of the discontinuity surface (Krohn and Thompson,1986;Bae et al.,2011).A structured-light scanner is a 3D scanning tool that uses projected alternating stripes and a camera system to compute an object’s 3D geometry (Grasselli,2001;Liu et al.,2017a).In comparison to other 3D scanning techniques,it has a number of benefits,including portability,high accuracy,fast speed,and a preference for small to medium-sized objects.Laser scanning method for roughness measurement is based on measuring the distance to the object using lasers according to the speed of light (Fardin et al.,2001,2004;Lee et al.,2001;Fardin,2008;Ge et al.,2014;Zheng et al.,2021).A pulsed beam of light is emitted,and the time it takes to return after reflecting off some surface is measured and used to calculate the relative distance to that surface.Additionally,based on the statistical information of joint surfaces measured by the abovementioned method,some researchers did productive work on the reconstruction of rock joints (Ficker and Martisek,2016;Nie et al.,2019;Liu et al.,2022).However,given the length of the paper,these non-contact methods are only briefly introduced as above.

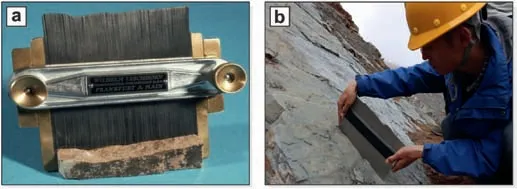

3.1.Profile combs

Barton and Choubey (1977) used a commercially available but high-quality device (Fig.4a) that allowed a large number (4 per mm) 0.25 mm thin steel shims to perfectly fit the surface of the joint surface along three chosen directions and locations(at 1/4,1/2 and 3/4 of the sample width) across their joint planes,giving 390 profiles for 130 joint samples.Fig.4b shows an example of the operation of a profile comb.A small amount of force will overcome the friction between the plates and the pins (as typically found in simpler devices) so that the complete array of pins can be pushed against an irregular surface and adjusted to fit the joint profile.It should be noted that Barton’s and Choubey’s device did not have the assumed 1 mm resolution with ‘steps’,but consisted of flat stainless steel metal shims,approximately 4 per mm.It means that the resolution of this device is 0.25 mm instead of 1 mm assumed by many researchers.Yong et al.(2018)proved that this resolution is sufficient for the measurement of joint roughness.When a larger sampling interval is used,measured joint surfaces generally tend to be smoother and the information about the subprime irregular undulations between smaller horizontal spacing may not be efficiently collected.Later,to facilitate the quantification ofJRC,Özvan et al.(2014) developed a profile digitization process that converts recorded profiles into image files and extracts coordinates based on the actual length of the profile.Hencher and Richards(2015)noted that these typical devices and methods are sufficiently precise for recording and characterizing the overall nature of joints for geological and geotechnical characterization.However,the measurement range of this type of device generally cannot exceed 400 mm.It has significant limitations in determining the roughness of larger-scale profiles.

Fig.4.Joint roughness measurement using the profile combs: (a) High-quality gauge used by Barton and Choubey (1977),and (b) The operation of a profile comb.

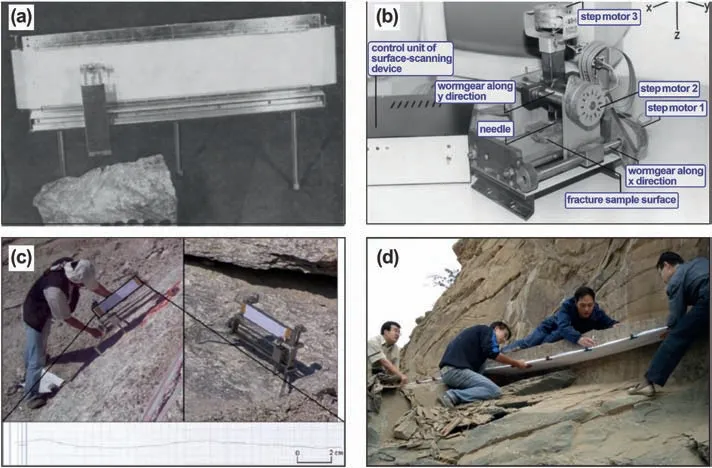

3.2.Roller and stylus profilometers

A mechanical profilometer usually consists of a stylus or small roller placed in direct contact with a rock joint surface and moved laterally over it.As the stylus or roller is moved laterally,the topography of the surface causes the stylus to be displaced vertically.For this method,the accuracy of the measurement is usually influenced by the diameter of the stylus/roller and the stick-slip motion of the needle on the surface.It is a useful method but can damage weak joint surfaces during measurements.Mechanical profilometers are commonly used for estimating small-scale joint roughness,and the traces of these linear profiles typically exhibit a basic size of a few centimeters (Fig.5a and b).

Fig.5.Joint roughness measurement in the laboratory and in the field using the profilometers: (a) The profilometer developed by Imperial College,U.K.(after Ross Brown and Walton,1975);(b) A mechanized computer-controlled profilometer (after Develi et al.,2001);(c) A manual profilometer for field use (after Tanyas and Ulusay,2013);and (d) A mechanical hand profilograph developed by Du (1992) for the roughness field measurement of rock joints several meters in length.

The profilometers have also been successfully used to carry out measurements under field conditions (Fig.5c),albeit less conveniently.To facilitate the measurement,Du (1992) developed a simple mechanical hand profilograph for measuring large-scale rock joint profiles in the field (Fig.5d).This instrument has the advantages of simple principles of operation,its lightweight,and the continuous roughness-profile drawing.Furthermore,the curve can be obtained quickly,and the measurement length can be extended by adjusting the length of the fixed board.Using this profilograph,the maximum length of the natural joint profiles he measured in the field exceeded 7 m long.The measurements were carried out on a tufa joint in Lin’an,Zhejiang Province,China.To facilitate the quantification ofJRC,the measured joint profiles need further digitization.Yong et al.(2017)proposed the grayscale image processing technique for digitizing joint profiles.Based on this technique,the obtained profile coordinates have high precision(the measuring error was negligible at approximately 0.1 mm)and can be acquired with flexible sampling intervals.In addition,the largest obstacle to applying this technique in the field is the location of the exposed rock joints,which should be accessible and have enough space for measurement.

3.3.Straight edges and rulers

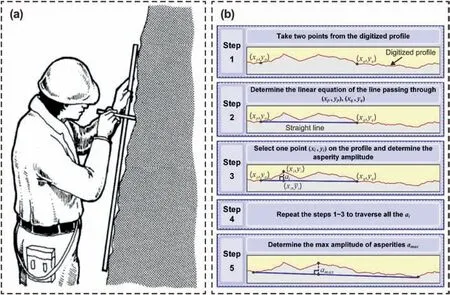

The dilatation behavior is highly dependent on the asperity amplitude,and the maximum amplitude usually plays the most important role in controlling the shear strength of rock joints.For field estimates ofJRC,Barton (1981) proposed the relations between theJRCand the maximum amplitude(amax)measured over a sample length (L).The value ofamaxcan be measured using a straight edge that is placed on the exposed rock joint surface along a length ofL.

Ideally,the edge length should be the same size as the joint.However,considering the limitations and difficulties of roughness measurement in field conditions,it is seldom possible to observe or measure the full length of the joint;as a result,the determination of undulations is often simplified(Piteau,1970).The orientation of the edge,together with the maximum amplitude,should be recorded.The simplified undulation can be calculated as

Due to the time-consuming nature of the measurement in Fig.6a,the joint waviness can be roughly assessed from visual inspection.To improve the measurement process,Du et al.(2022a)provided a programmed method for determining the maximum amplitude of asperities.Fig.6b shows a flowchart outlining the stages in determiningamax.It has been verified that this method can effectively estimate theJRCvalue of rock joints at the field scale.Based on the acquired amplitude of asperities for individual lengths between straight-edge contact points,Barton(1981)was the first to show how theJRCvalue could be estimated for a wide range of block sizes using a straight edge.This method is introduced in Section 4.

Fig.6.Joint roughness measurement using straight edges and rulers(a)measuring joint trace amplitude(after Milne et al.,1991),and(b)flowchart illustrating the steps involved in amax determination (after Du et al.2022a).

4.Estimation of the JRC

4.1.Visual comparison methods

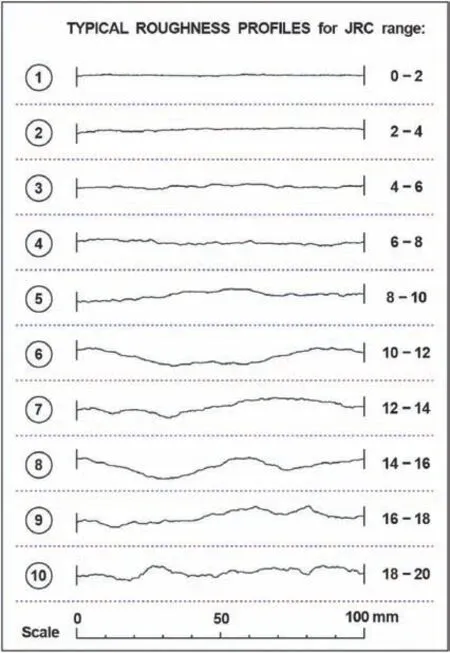

Barton and Choubey (1977) while illustrating the range of rock joint surfaces they had tested,produced the unintended subjective method to estimate theJRCof a measured profile.They characterized and tested 136 natural rock joints from seven different rock types,and in each case,three profiles were measured for each specimen.TheJRCvalues back-calculated from shear box tests were classified into the subsequent ranges: 0-2,2-4,etc.,up to 18-20.Wherever the mean joint plane was not inside ±1°of horizontal once placed within the shear box,the shear strengths and correspondingJRCvalues were corrected to the horizontal plane.An effort was then made to pick out the most typical profiles of every cluster.As a result,ten typical profiles were selected from 390 profiles(three per specimen).To assign an approximateJRCvalue to a joint,the measured profile can be visually compared against the typical profiles,as shown in Fig.7.Note that only rough guidance on likelyJRCvalue ranges can be provided by the typical profiles,and there are no decimal places.In fact,the ten typical profiles,with suggestedJRCranges,e.g.8 to 10 and 14 to 16,just illustrate the range of surfaces tested.There are 380 other roughness profiles since there were three per specimen.The main focus was the accuracy of the peak shear strength prediction.

Fig.7.Typical roughness profiles for the JRC range (Barton and Choubey,1977).

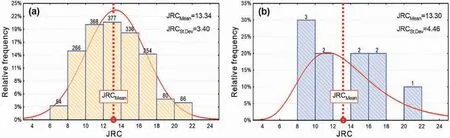

The visual comparison method is in fact suggested by the ISRM to characterize the small-scale roughness of rock joints (Barton,1978).However,as some researchers are concerned,the visual comparison method is subjective and may cause biases in theJRCestimates.For example,Beer et al.(2002)performed a survey based on three granite block profiles with 125,124 and 122 answers using an internet-based survey system to analyze the reliability of this visual comparison method.The result showed that the JRC mean value and standard deviation varied significantly until the sample size exceeded 50 people.Alameda-Hernández et al.(2014) performed a similar visual estimation survey in consideration of the knowledge and skill of the evaluators.Based on 12 test profiles,74 undergraduate students,9 post-graduate students,and 6 experts showed standard deviations ofJRCvalues ranging from 1.6 to 3.5,0.3 to 3.9,and 0.6 to 3.4,respectively.Although the accuracy ofJRCestimated by the visual comparison method can be improved by increasing experience and the number of people,the precision for problematic profiles,such as profiles not similar with the typical profile,stepped profiles,and profiles showing some similarity with one of the typical profiles but including different roughness amplitudes,can be seen to break down (Beer et al.,2002;Alameda-Hernández et al.,2014).Many efforts have been made to facilitate the application of visual comparisons to accurately estimateJRCs,and to reduce the subjective judgment of testers(Milne et al.,2009;Yong et al.,2017;Wang et al.,2019,2019nlüsoy and Süzen,2020).Since the essence of the visual comparison method is to assess the similarity between the target profile and typical profiles,image recognition,and deep learning techniques may be utilized to potentially estimate theJRCmore accurately.

4.2.Experimental methods

4.2.1.Direct shear tests

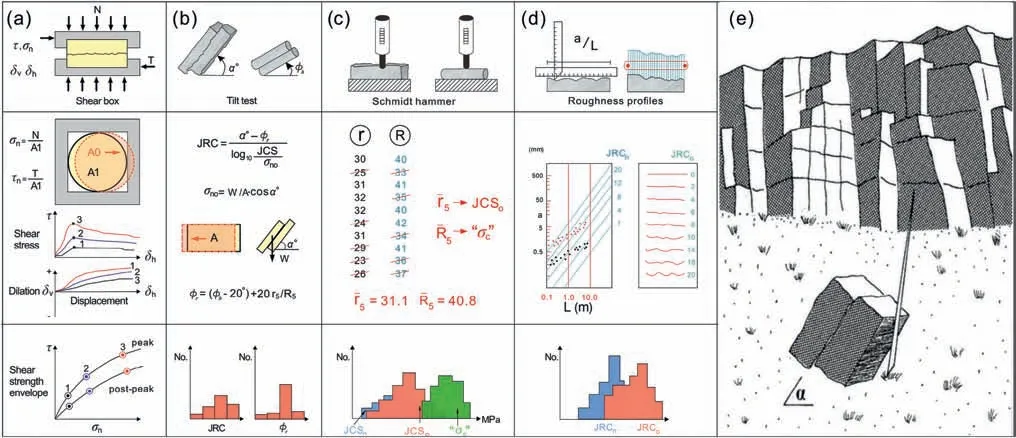

The typical direct shear test results are shown in Fig.8a.One may use joint samples with nearly circular (or elliptical) shapes prepared from the core,or samples with square (or rectangular)shapes prepared from sawn blocks,to perform direct shear tests.It is strongly recommended that both adequate and representative samples be recovered from each joint set of relevance.Multiple testing of the same sample must be avoided.In the case of the latter testing procedure,the effective‘friction’of the joint specimen tends to be gradually decreased because of the accumulation of damage with successive shearing of the same joint specimen.As Barton(2013) discussed,the multiple testing of the same sample tends to obtain an artificial ‘cohesion’ value because the strength envelope is slightly rotated (‘clockwise’).Through performing direct shear tests,the shear stress versus displacement and dilation versus displacement curves can be obtained(similar to the sketches in the middle of Fig.8a).The bottom of Fig.8a shows typical‘peak’and‘ultimate’ strength envelopes.These envelopes will tend to be curved for rough joints.Based on the direct shear test results,theJRCvalues can be estimated by back-analyzing the test results through Eq.(10).It should be noted that arctan(τ/σn)=70°was a conservative suggested maximum allowable total friction angle for back-calculating theJRCbased on direct shear tests (Barton and Choubey,1977).

Fig.8.(a)Typical direct shear test results(Note:avoid moment:use in-line shear forces);(b)Tilt test for JRC and φr estimates;(c)Schmidt hammer testing for r(weathered joint)and R(unweathered core stick);(d)JRC measurement using the amplitude/length(a/L)method,or brush-gauge recording;and(e)Ideally use natural block size to perform tilt test(after Barton,2013).

4.2.2.Tilt tests

Fig.8b and e illustrates the tilt test performed on a rough joint.When sliding occurs,we can obtain a tilt angle (α).The value ofαwill be larger thanφrdue to the geometrical effect of roughness.Theoretically,theαfollows a simple relationship:

where τ0is the shear stress andσn0is the normal stress acting on the joint.

Considering that the length-scale of specimens used to conduct tilt tests is not infinite,Barton and Choubey (1977) used the following empirical relation to estimatingσn0:

wherebis the thickness of the top half of the joint (m).

Then,theJRCcan be estimated by substituting the values ofα,σn0andφrinto Eq.(15):

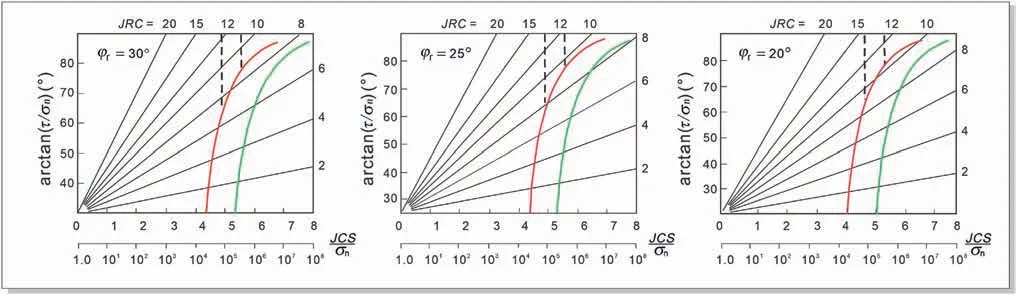

In fact,the normal stress acting on the joint is uneven.When tilt tests are performed on rock joints with significant roughness,overturning failure may be encountered.Eq.(14) somewhat accommodates the unequal stress distribution while barely impacting theJRCcalculation.More importantly,it automatically restricts the tilt test to joint surfaces that are ‘smooth’ enough to avoid overturning failure.Fig.9 presents the range of applications of tilt tests for estimatingJRCvalues (Barton and Choubey,1977) based on three realistic values ofφr.Two values ofbwere assumed: 20 mm for laboratory samples (green curve) and 200 mm for field joints(red curve).The value ofJCSdiscussed here is 100 MPa.The curves(red and green)in Fig.9 were evaluated by Eq.(14).Fig.9 shows the maximum value of theJRCthat can be obtained from the tilt tests decreases with increasingφr.Taking the test of Barton and Choubey(1977) as an example (the mean ofφrwas 27.5°),the laboratory scale tilt testing can provide a maximum value ofJRCof roughly 8.The limitingJRCvalue will be at least 10 if field-scale tilt tests are conducted on heavily weathered joints(φr=20°),especially if theJCSvalue is low because of weathering effects.Given that smoother joints are the primary source of stability issues,the aforementioned tilt test limits frequently will not be significant.

Fig.9.Range of application of tilt tests and push/pull tests for determining JRC values of joints (after Barton and Choubey,1977).

4.2.3.Push or pull tests

TheJRCvalues of rougher joints can be estimated using the‘push’ or ‘pull’ tests.In the tests,a joint’s upper half is pushed or pulled parallel to the joint plane while the bottom half is positioned horizontally.The weight of the upper half of the joint is the only additional typical load in this situation.Employing this test,theJRCof rougher joints can be reliably obtained.The approximate range ofJRCthat may be examined using‘push’or‘pull’tests is shown by the stippled lines in Fig.9.As presented by Barton and Choubey(1977),the maximumJRCvalue for the 136 specimens with a meanφrvalue of 27.5°that could be satisfactorily obtained with the push or pull tests was approximately 12.TheJRCvalue of joints as rough asJRC=20 can be safely determined by doing field‘push’or‘pull’tests on larger and more weathered joints (in this instance,theJCS/σnmay be as much as two orders of magnitude lower).Therefore,utilizing a combination of tilt and‘push’or‘pull’tests,it should be feasible to quantify the whole range of joint roughness.Additionally,JRC is essentially a constant for a given joint since it does not appear to vary significantly even over a stress range of up to fiveorders of magnitude(Barton and Choubey,1977).Other studies by Barton (1976) have indicated that this extrapolation may also be performed for very rough joints and over a stress range of up toeightorders of magnitude,spanning the whole brittle range of behavior.

4.3.Amplitude/length (a/L) methods

Visual comparison and experimental methods can be used to estimate theJRCfor profiles within the laboratory scale (i.e.100 mm).However,rock joints in the field,or more correctly rock block sizes in thefield,will usually be longer than 100 mm ‘Rock block sizes in the field’ is emphasized here due to the results of biaxial shear tests on assemblies of fractured blocks of widely different sizes.These exhibited scale effects will be shown in Section 7.1.In this case,a scale-correctedJRCshould be estimated for large-scale exposures of the relevant joint set.Based on the analysis of some 200 roughness profiles measured on 0.06 m and 0.1 m long and many times longer joint samples (Barton and Choubey,1977;Bandis,1980;Bandis et al.,1981),thus including the tests on model replicas of joints of different roughness,the following approximate relationships were proposed to estimate the scale-correctedJRCby Barton (1981):

whereais the maximum amplitude measured over a joint sample,andLis the sample length.

Based on the relationships presented in Eq.(16),Barton (1981)developed a simple straight-edge method,as shown in Fig.10.Through the straight edge method,values of the maximum amplitude (a)measured over a sample length (L) of 0.1 m or up to 1 m and occasionally up to several meters can be used to obtain a rough estimate of theJRCat the appropriate scale.Note that in practice,when laying a straight edge along a joint plane,there may be intermediate contact points for the straight edge and correspondingly smaller amplitudes.These should all be recorded,making a ‘cloud’ of results (representing roughness variation at different scales).The diagram is then used to extrapolate the approximateJRCvalue for the desired block size.Block sizeis given by the mean spacing of joints crossing the joint in question.

Fig.10.Joint roughness amplitude/length on various measurement lengths provides estimates of JRC when extrapolated to the desired mean block length (from the mean spacing of cross-joints).This may be of a larger dimension than the available straightedge lengths (after Barton,1981).

Du (1993) examined the straight edge method using the statistical data of theJRCmeasured from rock joints in Xiaolangdi,China.These researchers pointed out that the measurement accuracy of the straight edge method is sufficient to meet the requirements ofJRCestimates for the surface morphology of rock joints with undulations on the order of millimeters.In addition,the straight edge method has the advantages of being simple and fast.These co-workers also found that theJRCin engineering practice can sometimes be greater than 20.This was also found in measurements of a rough bedding plane in limestone at the Karun IV arch dam in Iran.Maximum smaller-scale values ofJRCof up to 30 were suggested,but when extrapolated to 2 m block sizes,JRCwas 11.Because of the sometimes largerJRCvalues,Du et al.(1996)proposed a modified straight-edge method (Eq.(17)):

whereL0is the sample length of a joint at the laboratory scale(100 mm).

Considering the small angle approximation tan(i)=i(herein,the angleiequals 8a/L),Eq.(17) implies that JRC is equal to 400-500 times the overall angle of inclination associated with the highest amplitude (i.e.‘first order’) asperity of the joint.Thus,in a logical conclusion,Eq.(17) implies thatJRCmight be directly proportional to the first-order asperity angle.It should be noted thatJRCis a mechanical parameter that describes the contribution of surface roughness and undulation to the shear strength of joints.It is a very important parameter in the BB criterion.In this criterion,JRC is not equal to the dilation angle or friction angle,but its effect on shear strength is related toJCSandσn.Additionally,the firstorder roughness (waviness) and the second-order roughness (unevenness) mutually govern the joint mechanical behavior.The estimation ofJRCvalues by ‘a/L’ approach is a simplified strategy based on the assumption that the shear strength of rock joints can be estimated approximately from the first-order roughness.Although the shear strength is mainly governed by the first-order roughness,different-order asperities are involved in the shear process.We have to admit that previous studies have commonly emphasized the relationship between the rock joint shear strength and the overall roughness.In the future,more attention should be paid to the accurate prediction of joint shear properties based on the quantitative evaluation of independent contributions of waviness and unevenness.

To estimate theJRCvalues of joints with laboratory scales,Du et al.(2009) proposed abasal roughness ruler.As shown in Fig.11,theeffective lengthandwidthof the ruler are 10 cm and 1.5 cm,respectively.This ruler is manufactured from 3 mm thick biological glass.On the left side of the ruler is noted the amplitude of a joint profileRy0.The appropriateJRCvalue of a joint with laboratory scale (JRC0) is shown on the right side of the ruler.

Fig.11.A basal roughness ruler for the measurement of JRC0 of profiles with 10 cm(after Du et al.,2009).Ry0 is the amplitude of a joint profile,and JRC0 is the JRC value of a joint with a laboratory scale.

4.4.Summary

Until now,the visual comparison,experimental(particularly the tilt test),and amplitude/length(a/L)methods are the most practical and readily available methods for estimating theJRC.Among them,tilt testing anda/Lmethods are recommended in engineering practice because the visual comparison method is inevitably subjective (Barton and Bandis,2017).Additionally,the statistical and fractal theories have been introduced toJRCestimations (e.g.Tse and Cruden,1979;Yu and Vayssade,1991;Kulatilake et al.,2006;Tatone and Grasselli,2010;and many others).The statistical and fractal methods rely on establishing relationships between theJRCand statistical parameters or fractal dimensions.For example,there is a strong correlation between theJRCand the standard deviation of the inclination angle,SDi(Yu and Vayssade,1991).Pre-JRCdevelopment,the importance ofSDiand its close resemblance to peak dilation angles when shearing rough tension fractures were demonstrated in Barton (1971) (see also Seidel and Haberfield,1995).Both the self-similar and self-affine fractals have been suggested for quantifying rock joint roughness.However,rock joint surfaces are self-affine.Thus,problems are encountered when selfsimilar methods are used in the calculation of fractal dimensions for self-affine rock joints (Kulatilake et al.,2006,2021).With the development of computer technology and increasedJRCdatabases,artificial intelligence (AI) methods,such as artificial neural networks,support vector machines,and random forests,have been adopted to estimate theJRC(Wang et al.,2017).The ability of AI to solve nonlinear problems and the efficiency of AI with regard toJRCpredictions have promoted the accurate estimation ofJRC.However,many of them concentrate on the exclusive use of 3D-laser profiling of roughness,and may be omitting certain crucial shear behavior features by never performing(3D)tilt tests while correctly criticizing the over-simplified 2D roughness profiles.The tilt test used for estimatingJRCis a back-analysis method incorporating two other parameters from the Barton (1973) shear strength criterion:JCSandφr.This cannot of course apply to 3D surface scanning methods in general,unless relating back to profiles linked to shear strength.When focusing on the various mathematical links between 3D laser scanning of roughness and the‘ten standard(2D)profiles’ of Barton and Choubey (1977),potential developers and users should be aware of the implicit ‘presence’ of the other two parameters in the approximately representative profiles.

Some recommendations for JRC in engineering applications are listed below:

(1) TheJRCjoint roughness coefficient is part of a threeparameters shear strength and joint behavior criterion(involvingJRC,JCSandφr) that allows for estimation and extrapolation of shear strength,dilation,normal stiffness and also allows for joint aperture estimation if Lugeon tests have been performed.Scaling rules for the known effect of block size were formally available after the contributions of Bandis in 1980,who also was responsible for the highly nonlinear normal closure formulations usingJRCandJCS.

(2) As is well known,there is considerable subjectivity when using only 2D profiling,and eventual anisotropy is limited by the direction of the measured profile.Clearly,profiling in the adverse (stability-dependent) direction is advised,as would also be needed in the case of preparing samples for tilttesting.This will often be down-dip since adverse shear stress is the focus.In the case of dam abutments,net effective thrust directions need to be considered.

(3) A recommended approach is to sample the joints of relevant joint sets by recovery in good-quality drill-core,with frequent use of a diamond saw to help form slender jointed samples.These are less likely to topple before sliding in selfweight (gravity-loaded) tilt-test angles,which are typically in the range 50°-75°.Index tests as shown in Fig.8 are recommended for estimatingJCSandφr.

(4) Scale effects can be allowed for by using the representative block size which is given by the mean spacing of cross-joints.In a realistic UDEC-BB model,each set is likely to have different scaling ratiosLn/L0,whereL0represents the representative length of the tilt tests performed,separated into different sets.Lnrepresents the relevant block sizes (i.e.respective mean spacings of cross-joints).

(5) There are typically kilometers,tens of kilometers,sometimes hundreds of kilometers of core in moderate-scale tunnel,hydropower,dam and mining projects.There should not then be the necessity ofmulti-stage shear testing,which artificially increases the (M -C) cohesion component and reduces the (M -C) friction angle.Tilt testing,though repeated several times to obtain mean values,is not adversely damaging the sample as in the case ofmulti-stage shear testingas normal stresses when sliding occurs in a tilt test may be as low as 0.001-0.002 MPa.

5.Investigation of the anisotropy and scale effect of joint roughness based on the JRC

5.1.Anisotropy

In the title of their paper,Barton and Quadros(2015)stated that‘anisotropy is everywhere’ in rock engineering,and anisotropic behavior is widespread because of the combined effects of anisotropic structures.Rock joints are formed through diverse,complex fracture mechanisms;this,coupled with the general complexities of rock masses,results in the significant anisotropy of rock joint surfaces.The variation in the joint roughness with respect to different orientations has been recognized as an important source of anisotropic behaviors in rock joints (e.g.Jing et al.,1992;Bae et al.,2011;Yan et al.,2020;Yong et al.,2020).

Diaz et al.(2017) investigated roughness anisotropy based on theJRCvalues of different orientations and suggested a method that can describe the roughness anisotropy of square as well as irregular sampling areas.Rock joints are produced by the action of stress:shear stress and tensile stress,and extension strain (Barton and Shen,2018).Therefore,rock joints can be divided into two types:shear joints and tensile joints.Shear joints usually extend far along the strike,their attitude occurrence is relatively stable,and their surfaces are relatively planar.The extents of the tensile joints tend to be shorter,their attitude occurrence is often variable,and their joint surfaces tend to be rough at a small scale unless developed when there is strong stress anisotropy (Olson and Pollard,1991).However,extension fracturing due to an adverse ratio of tensile strength and Poisson’s ratio has been responsible for remarkably planar and extensive sheeting joints,as seen in mountain walls(Barton and Shen,2018).

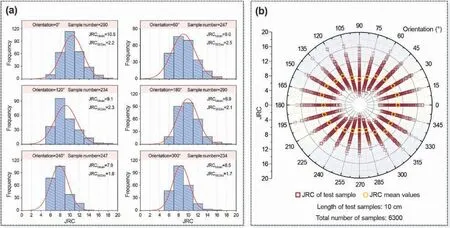

Peng et al.(2019)studied the influence of roughness anisotropy on the shear behavior of both shear and tensile joints.They found that compared with other roughness parameters (e.g.average dip angle and fractal dimension),theJRCvalue can be an effective indicator for analyzing roughness anisotropy.Later,Yong et al.(2019)concluded that statistical analysis of theJRCmight increase the precision and dependability of the roughness estimation results.Bao et al.(2020)studied roughness anisotropy based on 31 natural joint samples.A 3D laser scanning approach was used for digitizing the joint morphology,and theJRCvalues in different orientations were obtained,considering the influences of the sampling interval(SI) on theJRCcalculation process.It was discovered that theJRCvalues exhibited notable anisotropy and substantial variance in particular orientations.In the above studies,there is a consistent conclusion that the roughness of the joint surface has a distinct directionality.In addition to theJRC,the 3D directional roughness metricis the maximum apparent asperity inclination,andCis an empirical fitting parameter) and corresponding 2D directional roughness metricalso reflected obvious roughness anisotropy (Grasselli,2001;Grasselli et al.,2002;Tatone,2009;Tatone and Grasselli,2009,2010;Magsipoc et al.,2020).Of course,the joints selected for such testing may represent a biased sample with anisotropy obvious to see.However,the polar plots of theJRCfail to quantify the roughness variations due to the difficulty in mathematically describing the irregular patterns ofJRCpolar plots.

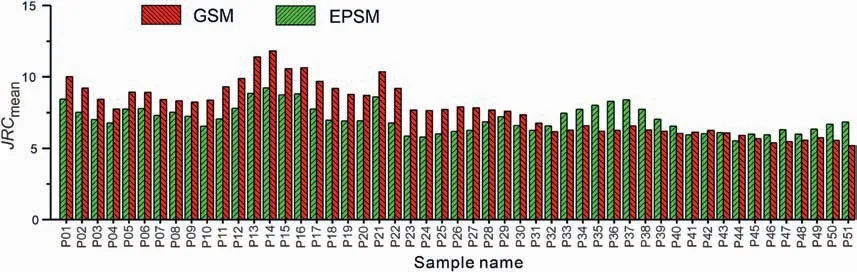

Yong et al.(2019) suggested aclass ratio transform methodto quantify roughness anisotropy.By doing so,theJRC’s directional variability frequently displays a comparatively systematic fluctuation that can be described by the ellipse function with high fitting precision.Du et al.(2021)studied the anisotropy characteristics of rock joint roughness throughJRCstatistical analysis.As shown in Fig.12a,the frequency histograms ofJRCvalues in the same orientation follow normal distributions.The polar plots of the meanJRCvalues in different orientations were applied to represent the roughness anisotropy of the entire joint surface(Fig.12b).It shows that the results based on statistical analysis also show irregular roughness in different orientations.Therefore,they characterized the anisotropy of joint roughness by local anisotropy and global anisotropy.The local anisotropy indicates the variation between adjacent orientations,and the global anisotropy reflects the difference between major and minor values ofJRCin various orientations.

Fig.12.(a)The frequency histograms of JRC values in orientations of 0°,60°,120°,180°,240° and 300°;and(b)The polar plots of the JRC values in steps of 15° from 0° to 360° (after Du et al.,2021).

5.2.Scale effect

The scale effect impacts the strength and deformability of rock joints.Since the 1970s,the scale dependence of the strength of rock joints has been studied by many researchers (e.g.Barton,1973;Barton and Choubey,1977;Bandis,1980;Bandis et al.,1981;Barton,1982;Barton et al.,1985;Du and Fan,1999;Johansson,2009;Tatone and Grasselli,2010;Hencher and Richards,2015;Yong et al.,2017).The main reason behind the generally assumed ‘negative’shear strength scale effect (i.e.reduction with size) is that roughness,a key parameter controlling shear strength,is itself scaledependent.Hence,the variations in the roughness of rock joints with different sizes,including anisotropy,need to be thoroughly considered.

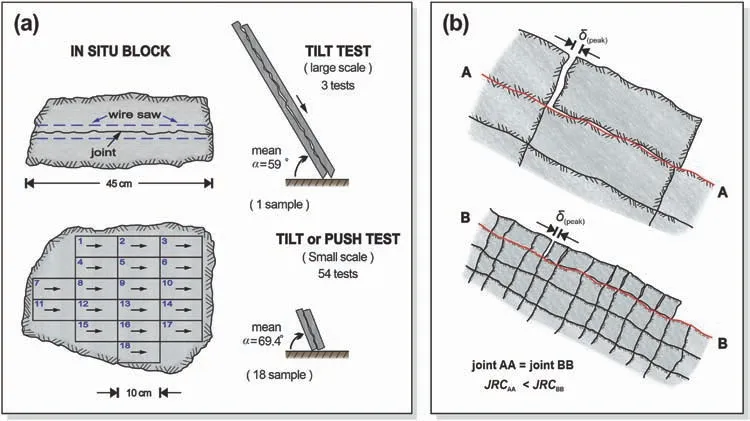

In practice,it is found that theJRCis scale-dependent.Usually,longer profiles or larger blocks containing the same joint have lowerJRCvalues.Two examples of the scale effects on rock joints are illustrated in Fig.13.As shown in Fig.13a,tilt tests were conducted to evaluate theJRCvalues of the larger and smaller samples obtained from the same natural rock joint (Barton and Choubey,1977).The tilt angle was always 59°for the 45 cm long sample.Then,the large joint sample was sawed into 18 equal samples with a size of 4.8 cm×9.8 cm.The mean tilt angle of these small samples was 67.2°.Based on the back analysis,the calculatedJRCvalue for the large sample was 5.2,but the mean value was 8.8 for the small samples.Fig.13b shows that smaller blocks have greater freedom to follow and ’feel’ the smaller scale and steeper asperities of the component joints;hence,higherJRCvalues are evident.Therefore,a joint with small,steep asperities influencing peak behavior would have a greaterJRCvalue at small scale than a longer profile of the same joint where larger,less steeply inclined surface features will determine the joint’s behavior.

Fig.13.(a)Scale effect investigation with tilt tests of a 45 cm long joint in granite,followed by individual tilt tests on eighteen component samples from the same joint,sheared in the same direction;and (b) Contrasting effective JRC of widely and close spaced joints (after Barton and Choubey,1977).

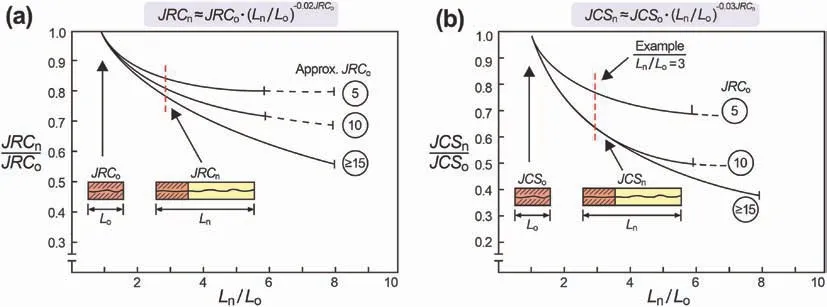

The scale dependence of theJRCwas also clearly demonstrated by Bandis et al.(1981) through a comprehensive series of shear tests.Based on the results of extensive testing of rock joints,joint replicas,and a comprehensive survey of the literature,Barton and Bandis (1982) presentedJRC,JCSscale correction curves,as shown in Fig.14,and the following equations for describing the reductions in theJRCandJCSwith increasing sample size were suggested:

Fig.14.Scale effect correction for JRC and JCS (Barton and Bandis,1982).

whereJRCoandJCSorefer to theJRCandJCSwhen measured in the laboratory with a nominal length ofLo=100 mm (or similar) andJRCnandJCSnrefer to theJRCandJCSwhen extrapolated to the desired length ofLn.The latter is expected to be the relevant block size given by the mean spacing of cross-joints.

Based on the statistical analysis of theJRCvalues of 1157 joint profiles obtained from Xiaolangdi Reservoir Area,Du (1992)developed a similar method for various size-dependent characterizations of joint roughness.The fractal expression of theJRCand the sample size is given as follows:

whereDnis the fractal dimension of theJRCscale effect,which defines the magnitude of the change inJRCnthat decreases as the sample lengthLnincreases.For the convenience of engineering application of the scale effect laws in Eq.(20),Du and Fan (1999)proposed a method forDndetermination based on its relationship to the back-calculated fractal dimension(D3)of 300 mm long joint profiles.They summarized the value ofJRCoandD3for typical rock joints based on a comprehensive study of 11,064 joint profiles obtained from 16 different rock types.

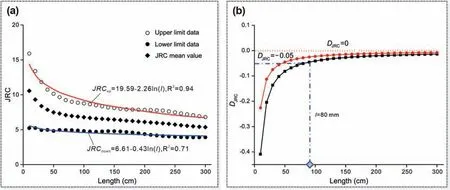

The joint roughness can be characterized by two components:waviness (large-scale undulation) and unevenness (small-scale roughness).The waviness becomes more dominant with the increasing scale of rock joints,while the significance of the unevenness decreases.Barton and Choubey (1977) suggested that the correct size of the joint for indexing (shear testing or surface analysis) might,as a first approximation,be given by the natural block size (specifically the spacing of cross-joints).This suggestion was reinforced by the biaxial testing of ‘2D slabs’ with 250,1000 and 4000 tension-fractured blocks by Barton,which was reported in Barton and Hansteen (1979) and in Bandis et al.(1981).This block size study was made using the same model tension fracture techniques Barton had used a decade earlier in his model slope stability studies with 40,000 blocks.Later,some researchers found that the surface roughness becomes statistically stationary when the scale of the rock joint (or block size) reaches a certain value.This size was defined as the stationarity threshold(ST)by Jing and Hudson(2004),and it is similar to the definition of representative elementary volume (REV) of fractured rock,which allows the establishment of representative geometric parameters for aggregates at fracture surfaces over a wide range.Theoretically,testing results taken using rock joint samples at a scale equivalent to or larger than itsSTare the only way to accurately determine the mechanical behavior of a rock joint.The results with sample sizes smaller thanSTcannot be directly applied to representing fracture behavior at field scales.For an accurate determination of the surface roughness of rock joints at a large scale,Yong et al.(2020) suggested a technique for the estimation ofSTbased onJRCstatistical analysis.They combined the lower/upper limits ofJRCand the mean values ofJRCfor the joint sample lengths from 100 mm to 3000 mm to investigate the scale effects on joint roughness (Fig.15a).Based on the derivative of theJRCneutrosophic functions,the variation trend of the relationship betweenJRCand the sample size was assessed.As shown in Fig.15b,the derivative suggested that theJRCvalue for small samples is more sensitive than theJRCvalue for large samples.It is recommended thatSTcan be determined when the derivative value is equal to -0.05 because the roughness behavior is almost independent of scale when the sample size exceeds the determined value.

Fig.15.(a) The lower and upper limits and the mean values of JRC of different-sized joint samples,and (b) The ST determination based on the derivative of JRC neutrosophic functions (after Yong et al.,2020).

5.3.Coupled behavior of anisotropy and scale effect of joint roughness

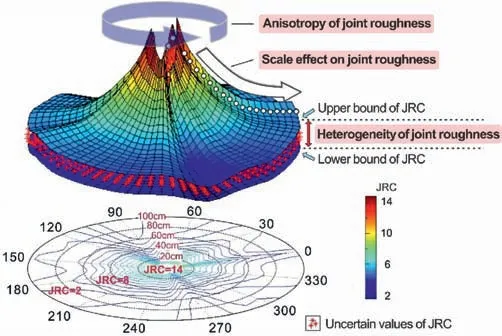

As we have just seen,surface roughness varies not only with orientation but also with scale.Since the properties of anisotropy and scale effects are not isolated but interrelated,some researchers have systematically studied the coupled behavior of anisotropy and the scale effects of joint roughness.Tatone (2009) studied the dependency of joint roughness on the sizes of sampling windows.He found that the roughness parameters in different orientations appear to converge to a constant value as the sample window size is increased,resulting in a decrease in anisotropy variation.Du et al.(2021) made a statistical analysis on theJRCvalues of 19,616 different-sized profiles.They found that the mean and standard deviation of theJRCin each orientation decreased with increasing profile size,indicating a negative scale effect on joint roughness.According to the variations ofJRCmean values in each orientation,they found that ST was 600 mm.When the sample size exceeded ST,the global anisotropy tended to remain constant.

Furthermore,heterogeneity,anisotropy,nonuniformity,and inherent scale effects are the characteristics of joint roughness,which naturally brings some uncertainty to the joint roughness measurements (Du and Pan,1992).Since there is incomplete and indeterminate information in theJRCvalues of different-sized samples at various orientations,it brings difficulties to investigate the coupled behavior of anisotropy and scale effect based on classical probability and statistics.To solve this problem,many researchers (Ye et al.,2017;Chen et al.,2017a,2017b;Yong et al.,2019;Song et al.,2021) proposed different methods based on neutrosophic theory to express the anisotropy based on theJRCdata of different-sized rock joints.Using these methods,the fuzzy information ofJRCis not lost,and the original information of the roughness properties is preserved to the greatest extent.As shown in Fig.16,the heterogeneity of the surface roughness is described by theJRCvalues,which are indeterminate between the upper and lower bounds,accounting for both the roughness anisotropy and the scale effect.Many excellent research groups did productive works on theJRCand rock joint shear strength,such as Barton et al.(Barton,1973,1982,1990,2013,2020;Barton and Choubey,1977;Barton and Bandis,1982,2017;Barton et al.,1985;Barton and Quadros,1997,2015,2019),Fardin et al.(Fardin et al.,2001,2004;Fardin,2008),Kulatilake et al.(Kulatilake et al.,2006,2021;Ge et al.,2014),Grasselli et al.(Grasselli,2001;Grasselli et al.,2002;Grasselli and Egger,2003;Tatone and Grasselli,2009,2010;Magsipoc et al.,2020),Du et al.(Ye et al.,2016,2017;Yong et al.,2017,2018a,2018b,2019,2020),Zhu et al.(Chen et al.,2015;Liu et al.,2021,2022),Liu et al.(Liu et al.,2017a,2017b,b;Tian et al.,2018a,2018b),and many others.Amongst the research groups worldwide,significant contributions have now been made to the topic of rock joint shear strength over the years.An example is the highly-acclaimed expert in China,Professor Shigui Du and his research group,who have made significant efforts and achievements in the theory,equipment,technology and engineering application of rock mass in terms of shear strength of sliding surfaces.They also realized an accurate acquisition of shear strength.It is exciting that Du’s research team has been becoming one of the promising academic research centers in rock mechanics in terms ofJRCand shear strength across the world.

Fig.16.Roughness characteristic description based on JRC.

6.Descriptions of properties of rock joints based on the JRC

Realistic characterization of the mechanical and hydraulic properties of rock joints has been an important goal of rock mass engineering for many years.Even simplified constitutive models demonstrate the extreme importance of joint characteristics.For example,a simple change in the friction angle from 40°to 30°may alter not only the magnitudes of deformation but also the type of deformation experienced by an excavation.In this section,we focus on the descriptions of the properties of rock joints based on theJRC.Other roughness parameters,such as fractal dimensions and statistical parameters that can potentially characterize the mechanical and hydraulic properties of rock joints exist (e.g.Goodman,1974;Jing et al.,1992;Grasselli and Egger,2003;Buzzi and Casagrande,2018;Kulatilake et al.,2021) but are not discussed here.

6.1.Shear stress-displacement behavior

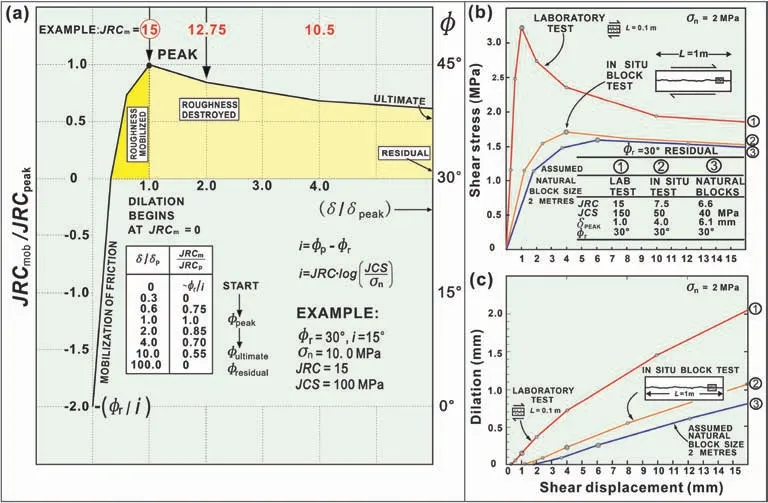

The shear behavior of rock joints is extremely significant in stability and deformation analyses of rock masses.TheJRC-JCSmodel can be conveniently applied in engineering practice based on some simple index tests.This empirical model was complemented by a joint match coefficient (JMC) proposed by Zhao(1997).These models initially considered just peak shear strength,and theJRCintroduced up to now is particularly correlated to the peak shear strength of rock joints.The peak shear strength of a rock join is actually mobilized by a small shear displacement (δpeak).As indicated by Barton and Bandis (1982),δpeakis approximately 1% of the length (L) of laboratory-scale samples (approximately 100 mm).However,δpeakmay be less than 0.01Lfor joints with lengths of several meters.It is found that the ratioδpeak/Lis correlated to theJRCand length of a rock joint(Bandis et al.,1981).Based on the data provided by Bandis et al.(1981),Barton (1982) proposed the following equation to estimate theδpeak:

During the shear displacement beforeδpeak,roughness and friction both mobilize initially,leading to dilation.Post-peak,roughness is gradually removed or worn away at displacements greater thanδpeak.After the peak,dilation continues at a slower rate.At any given shear displacement (δ),the strength is simply represented by the mobilized shear strength (τm),whose value is dependent on the magnitude ofJRCmobilized:

Barton(1982)demonstrated that the dimensionless coordinatesJRCmobilized/JRCpeakandδ/δpeakgrow and then decline essentially identically during shear for a wide variety of joint surfaces and stress levels.Fig.17 depicts examples of the behavior of shear stress versus displacement.The simplified table for non-planar joints,given as an insert in Fig.17,provides the essential coordinates for defining a full shear stress-displacement (and dilation) event.The resulting curves might vary from highly pointed to smooth and rounded,as seen when larger block sizes are modeled.

Fig.17.(a)Model suggested for producing realistic shear stress-displacement curves for non-planar joints,and(b,c)Examples of stress-displacement-dilation modeling with scale effect assumptions (Eq.(18) and (19)) given in the inset (after Barton,1982).

There are many other approaches describing the behavior of shear stress-displacement for rock joints,including three main categories: theoretical,empirical,and numerical simulation methods.To mimic the observed shear behavior of rock joints,the theoretical method employs established theories such as plasticity theory,contact theory,energy theory,adhesion theory,wear theory,and fractal geometry.In the empirical approach,empirical models are formulated by analyzing physical data obtained from test results and deriving correlations using variables of influence(as in Fig.17).The numerical simulation approach mainly adopts the discrete element method (DEM) or the finite element method(FEM)to simulate the shear behavior of rock joints.These methods for characterizing the shear behavior of rock joints aid scientists in comprehending the fundamental mechanical features of rock joints under shear.

6.2.Dilation behavior

When a nonplanar joint is sheared,the opposing asperities slide across each other,resulting in an increase in aperture.This dilation process begins with a limited displacement and progresses with an accelerating gradient as peak strength is approached.The dilation behavior has a considerable impact on the shear strength of rock joints.Goodman(1970),Barton (1973),and Pratt et al.(1974) have verified that peak dilation is reached at or shortly after peak shear strength,thus demonstrating a significant link between dilatancy and the peak shear strength of rock joints.

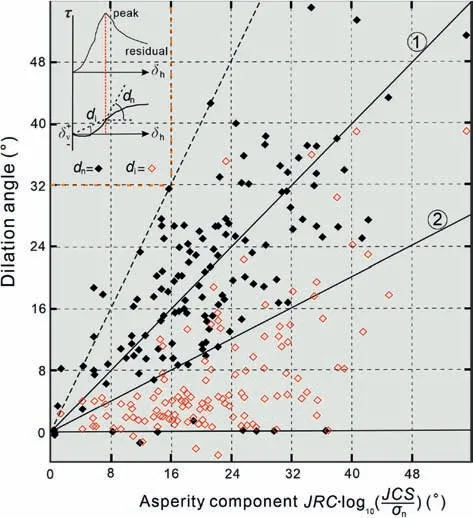

On the basis of the direct shear test findings of 136 specimens,Barton and Choubey(1977)examined the connection between the asperity component of peak strength and dilation angle.The asperity component is equal to the difference between the total friction angle measured (arctan(τ/σn)) and the residual friction angle estimated (φr).The peak dilation angle (dn) and the initial dilation angle (di) are shown plotted against the asperity component in Fig.18.The mean value of theinitialdilation angle (di) is approximately one-third of the asperity component,as seen in the graph:

Fig.18.Distribution of peak and initial dilation angles and their relationship with the asperity component of shear strength (after Barton and Choubey,1977).

while the majority ofpeakdilation angles (dn) fell between the following limits:

The value ofdnchanges with the applied normal stress level,theJRC,and theJCS.Where asperity damage is minimal (as a result of relatively highJCSvalues,lowσnvalues,or smallJRCvalues),the asperity componentJRClog10(JCS/σn) provides the best approximation of thedn.As seen in Fig.18,the middle envelope(line 1)is a near approximation of the mean performance of the 136 tested rock joint samples,though there is wide scatter.In contrast,the asperity component estimate ofJRClog10(JCS/σn)/2 provides a more accurate estimation of thednfor the 130 tests on tension fractures in model materials published by Barton (1971),in which the tests were conducted at normal stress levels that resulted in significantly greater asperity damage than that observed in Fig.18.Based on these observations and analysis,Barton and Choubey (1977)defined a joint damage coefficient (M) to correlate the peak friction angle and asperity components:

Shearing at low or high normal stress,respectively,results in a damage coefficient (M) of 1 or 2 (Olsson and Barton,2001).Alternatively,it may be approximated by the formula below(Barton and Choubey,1977):

Based on the appropriately selected damage coefficient(M)and mobilizedJRCvalues,the dilation-shear displacement behavior can be quantitatively obtained.For example,Xia et al.(2014) adopted Eq.(27) to estimate the peak joint dilatancy angle for their test results by assuming that the damage coefficient (M) equals 1 and proposed a peak dilatancy angle function using the roughness parameters derived by Grasselli et al.(2003).Notably,the value ofδ/δpeakat which dilation is supposed to begin is 0.3,both for nonplanar and planar joints (Barton,1982).

6.3.Joint closure behavior

For the study of the mechanical/hydromechanical behavior of rock masses,the closure behavior of rock joints under normal loads is of essential interest.It should be noted that the closure behavior of rock joints with or without filled materials is significantly different.For the filled joints,the closure behavior of rock joints mainly depends on the properties of filled materials,the degree of filling,and the roughness of joints(Ladanyi and Archambault,1977;Huang et al.,2018;Tian et al.,2018b).In this section,we mainly focus on the closure behavior of unfilled rock joints.Bandis(1980)found that the maximum closure(Vm)of joints with a comparable average value of initial aperture(aj)was predominantly determined by theJCS.Variations in theVmof joints with comparableJCSand aperture values were correlated with theJRC.Large values for the maximum closure were recorded for certain weathered joints,due to the combined impact of greater initial apertures and lowJCSvalues.The ratioJCS/ajwas found to be a sensitive indicator of this behavior;low ratios give large values ofVmand vice versa.An analysis of the experimental data reported by Bandis (1980)showed that the following simplified empirical relation gives a reasonable estimate of the initial unstressed aperture of a joint(Barton,1982):

whereajis the initial joint aperture expressed in mm under selfweight stress (approximately 0.001 MPa),andσcis the unconfined compressive strength of the intact rock.Bandis (1980) fit a wide range of experimental data for maximum closure,with the following empirical relationship:

whereA,B,C,andDare the constants obtained from experimental data.Notably,Eq.(28) is a simple constitutive equation that presents the differences in the maximum closure of unfilled interlocked joint types with the following range of wall strength and geometry indices,i.e.JRC=5-15,JCS=22-182 MPa,andaj=0.1-0.6 mm,the latter assuming that the initial stress condition does not exceed a level of approximately 0.001 MPa (i.e.essentially unstressed).Due to the nonlinear relationship between the closure deformation of the rock joint and the normal stress,Goodman(1974) proposed two hyperbolic functions to describe joint closure under normal stress,whereas Bandis (1980) derived a single hyperbolic model to describe the aperture deformation of a rock joint under normal stress.This hyperbolic model was shown to give an improved fit to experimental data when compared to the two hyperbolic functions suggested by Goodman (1974).It is expressed as follows:

whereaandbare the constants and ΔVjis the joint closure.Note that the asymptote of the hyperbola (a/b) equals the maximum joint closure (Vm),and that the constantaequals the reciprocal of the initial normal stiffness (Kni).Simplifying from Bandis (1980),Barton(1982)suggested that the initial normal stiffness(Kni)could be estimated by the following relationship:

Expressions forKniandVmtherefore define the complete stressclosure behavior of rock joints.Then,for each increase ofσn,the appropriateKnvalue may be calculated using the Bandis (1980)hyperbolic function derivative:

There have been several additional models created to represent the mechanical behavior of a joint under normal stress.There are three classifications for these models:empirical,theoretical and numerical.Empirical models are employed to fit experimental data with simple nonlinear mathematical functions(Swan,1983;Malama and Kulatilake,2003).Under normal load,theoretical models based on the Hertz contact theory may be utilized to estimate the closure deformation of joints(Greenwood and Williamson,1966;Greenwood and Tripp,1970;Brown and Scholz,1985).Multiple numerical models with asperities simulated by cylinders can account for both asperity deformations and rock deformations around the asperities (Cook,1992;Lee and Harrison,2001;Marache et al.,2008).

Considering the differences of influences between the waviness and unevenness components on the closure deformation,Xia et al.(2003) determined the impacts of the waviness and unevenness components based on a mathematical method and proposed a generic load-closure model.Based on the Xia et al.(2003) model,Tang et al.(2013) presented an improved model considering the deformation produced by asperity deformation and the interaction between asperities.Perhaps with some similarity to the latter,Barton(2020)recently suggested thatover-closureandthermal over-closureof rock joints,in which actual tensile strength is developed in the case of moderately-rough and rough rock joints,may be caused by the ‘perpendicular’ ‘JRC’ involving the friction between interlocking and sloping asperities.He suggested this has caused some of the reported difficulties with geothermal projects in which ‘cold’ injected water is‘captured’by joint sets with lowerJRCsince they will not be over-closed so can open due to the shrinkage/cooling and conduct water away from the‘producer’well,since shearing more readily as a result of their smoother character.

6.4.Conductivity of rock joints

Variations in the hydraulic conductivity of rock joints resulting from changes in normal or shear stresses are closely related to some engineering geological disasters at dam sites.The potential leakage of reservoirs,the leakage of contaminated radioactive water,the instability of dam foundations,slopes,and underground caverns,and the extraction of oil and gas are each related to the conductivity of rock joints and how this varies with changes of effective normal stress and eventual shearing and dilation.It is not possible to adequately predict the mechanical and hydraulic behavior of rock joints when exposed to a change in stress,unless an accurate method can be derived for measuring real joint apertures in situ prior to a stress perturbation.The unknown stress history of joints in situ means that the techniques developed in Section 6.3 only provide a crude approximation to apertures in situ,even if the present stress distribution is known.

Experiments in the laboratory have shown that the aperture and the roughness of a rock joint are the two most essential factors influencing fluid flow through the joint.

When modeling the influence of joint conductivity,at least two types of joint apertures must be considered: the mean physical aperture (E) and the (theoretical) hydraulic aperture (e) (Barton,1972;Barton,1982;Barton et al.,1985;Barton and Quadros,1997;Olsson and Barton,2001;and subsequently many other authors).The real physical aperture(E)is larger than the conducting aperture(e) for rough joints.How to link the hydraulic apertures (e) to the normally larger mean physical apertures(E)is thus a crucial topic.(Note that the mean physical apertureEincorporates the‘reducingof-the-mean’ effect of asperities/surfaces in local contact if and when transmitting positive effective normal stresses.)

Fig.19 displays test data from which apertureseandE(or Δeand ΔE) were measured (Barton et al.,1985,updated by Quadros in Barton and Quadros,1997),demonstrating that as the aperture lowers,the divergence betweeneandE(or Δeand ΔE) increases.The bars marked NS,EW and B represent large-scale block test data from Hardin et al.(1982) and indicate whether there was a shear stress component(NS or EW)or whether stresses were biaxial(B)resulting in pure normal stress across the test joint.It is apparent that the cubic law withE=e,may only be valid when joints are exceptionally smooth,or when apertures are very wide.These observations of the dependence ofE/eon the joint roughness and aperture lead to the formulation proposed in Fig.20.It can be seen that bias from the cubic equation(E=e)is modeled for rough joints of very wide aperture (≥1 mm).No divergence is modeled for the smoothest joints unless hydraulic apertures are very small (i.e.<10 μm).These features of the model broadly correspond with observed behavior.It also determines the types of contacts,and therefore indirectly the tortuosity of flow and the frictional drag resisting flow between joint walls.The following equation(Barton,1982) represents the curve in Fig.20:

Fig.19.Relationship between the ratio of mean physical aperture and the theoretical hydraulic aperture in terms of JRC,based on the parallel-plate flow analogy (after Barton and Quadros,1997).

Fig.20.A constitutive model relating hydraulic aperture with physical aperture and joint roughness (Barton,1982).

whereEandeare expressed in μm.An alternative form of this equation is given below:

Eqs.(32)and(33)are only applicable for values ofE/e≥1 with modest shear displacement and insignificant gouge generation.The joint closure is unlikely to be size-dependent,unlike the shear stress-displacement behavior,hence these equations enable one to linkEandeeven at the field scale (Barton,1982;Barton and Quadros,1997,2019).The above aperture equations are approximate(Barton,2020),but the formulae have been widely applied to converting hydraulically measuredeintoEat field scale for various geoengineering problems (Barton,1972,1982;Bandis et al.,1985;Barton and Bakhtar,1987;Bhasin et al.,2002;Ishii,2020)including for assisting in the choice of grout particle sizes using theE>4d95rule of thumb.This is apparently not used in Swedish pre-grouting of tunnels,where the theoretical hydraulice-aperture is (surprisingly) used for estimating grout entry.

7.Influences of the JRC on the properties of rock masses

Probably several million structures and constructions such as slopes,tunnels,and dams are distributed in a multitude of jointed and fractured rock masses,and these inevitably have almost worldwide locations.The properties of rock masses,including strength,deformation,and quality,are closely related to the properties of rock joints.Additionally,some interfaces such as rocksoil,concrete-rock,and clay-concrete also have significant influences on the properties of both natural and bolted rock masses.Engineering procedures commonly include bolted rock masses because it is the most efficient and cost-effective way to support excavations in rock masses.In this section,we focus on the influences ofJRCon the properties of natural rock masses,bolted rock masses,and some frequently encountered interfaces.

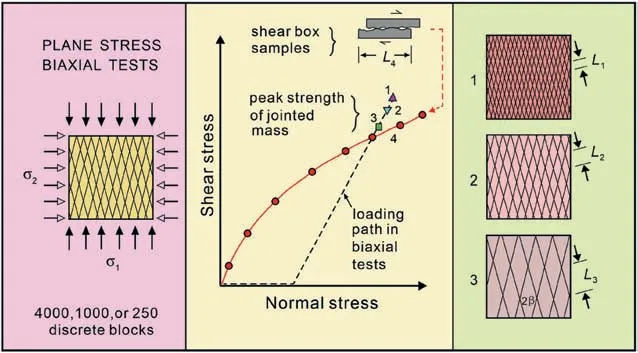

7.1.Natural rock masses

The characteristics of rock joints have a significant impact on the strength and deformability of rock masses.Barton and Bandis(1982) emphasized that the block size significantly affects the shear strength of jointed rocks.As shown in Fig.21,for an unchangedJRC,the shear strength of an assembly of blocks decreases with increasing block size.The biaxial shear tests shown in the figure were reported by Barton and Hansteen (1979) using the tension-fractured brittle model materials and the double-bladed guillotine to generate intersecting sets of equally spaced fractures,as used by Barton(1971).The experiments were conducted prior to large-span cavern modeling(for underground nuclear power plant uses),employing a variety of fracture configurations provided by 20,000 blocks and low and high horizontal stress levels.The tests were pre-UDEC and hence pre-UDEC-BB.Depending on the joint spacing used,each of the considerably smaller biaxial models was made up of 4000,1000 or 250 blocks.In every instance,the joint orientation(2β=36°)and loading route(constantσ2,risingσ1until failure)were the same.The additional freedom for block rotation in the case of the smallest-block models caused higher shear strength and allowed kink-band development.Nevertheless,the models with smaller blocks showed lower deformation moduli as expected.Shear box samples (lengthL4) in these physical model investigations may be longer than block size dimensionsL1,L2orL3,so may underestimate the jointed rock mass’s shear strength.By comparison,shear box samples are typically smaller than evenL1in the practice of rock mechanics and,unless scale-corrected,frequently overestimate the shear strength of the rock mass.

Fig.21.Shear strength scale effect due to block size (after Barton and Hansteen,1979 and Bandis et al.,1981.For further experimental details,see Barton and Bandis,1982).

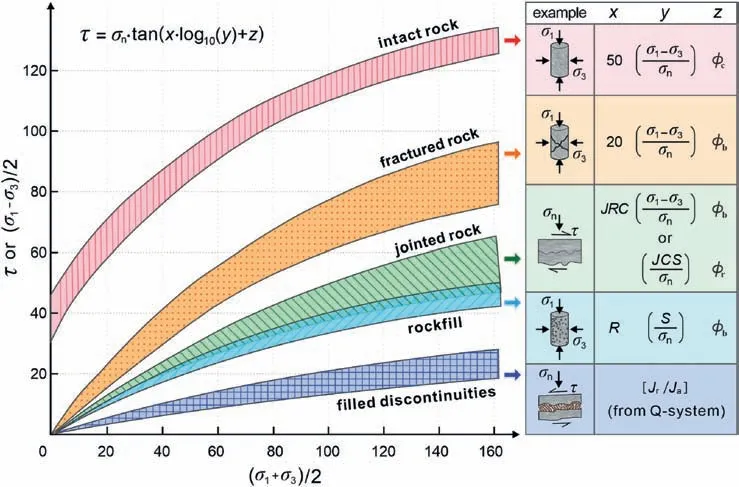

The characterization of rock joint properties has long been recognized as an important process in describing the properties of rock masses.This of course has been the reason for rock mass descriptive schemes like theQ-system with its several joint-related parameters.It will be discussed later.Since rock mass behavior is frequently dominated by joint behavior as opposed to modified intact rock curve fitting,Barton(1999)proposed easily understood empirical equations designed to symbolically represent theprogressively mobilizedstrength components of fractured and jointed rock,as assembled in Fig.22.Recently Barton (2021) ‘christened’these components CcSs(crack,crunch,scrape,swoosh)to represent the successive breakage of intact bridges,shearing on these new rough surfaces,mobilization of joint set responses,and finally engagement of any faults or major clay-filled discontinuities -in other words,the commonly experienced progressive failure and not the usually incorrect addition as in Mohr-Coulomb and Hoek-Brown of‘c+σntanφ’(linear or nonlinear:both will usually be incorrect).

Fig.22.Principal components of rock mass shear strength (intact,fractured,jointed,filled discontinuities) assembled by Barton (1999).Four of these five shear strength components have recently(Barton,2021)been adopted in a progressive failure concept termed CcSs representing the breakage of cohesion(‘crack’),shearing along these new surfaces(‘crunch’),shearing along kinematically capable rock joints(‘scrape’),and possible shearing along clay-filled discontinuities of faults(‘swoosh’).The components can be quantified using the x,y,z symbols shown in the inset.

7.2.Rock mass classification

Prior to any excavation or rock disturbance,rock mass classification is one of the most effective techniques in rock mechanics and a crucial component of feasibility assessments.To provide a quantitative indicator of rock mass quality and as guides for engineering design,certain rock mass classification systems,such as the rock mass rating RMR (Bieniawski,1973),the rock mass qualityQsystem (Barton et al.1974),and the simplistic geological strength index GSI(Hoek,1994),have been widely employed.Based partly on Norwegian and Swedish tunnel and cavern case records published by Cecil (1970),Barton et al.(1974) proposed the empirical rock mass classification system,i.e.theQ-system for the evaluation of rock mass characteristics and tunnel support requirements.TheRQDindex,the number of joint sets,the roughness of the weakest joints,the degree of modification or filling along the weakest joints,and two additional parameters that take into consideration the rock load and water inflow,are all factors that affect the rock mass qualityQ.The appropriatepermanent supportforthewholerangeofrockqualitiesmaybe estimatedusingtheQvalues,whichrangefrom0.001(forexceedingly low qualitysqueezing ground)to 1000(for exceptionallygood quality rockthatisnearlyunjointed).Thefollowingisacombination of thesix inputs used to define the quality of the rock mass:

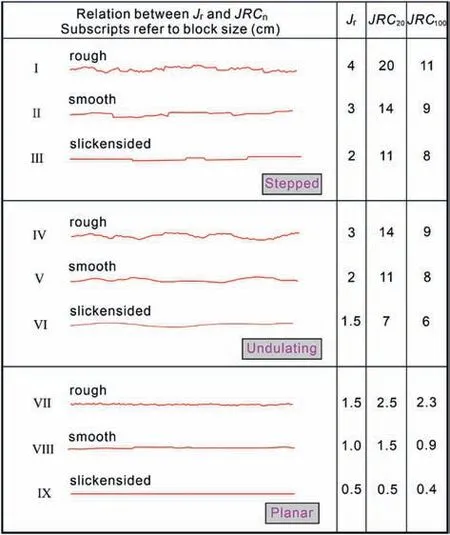

whereRQDis the rock quality designation (Deere,1963),Jnis the joint set number,Jris the joint roughness number,Jais the joint alteration number,Jwis the joint water reduction factor,andSRFis the stress reduction factor.RQD/Jnis a pair of characteristics that serves as a rough gauge for relative block size,Jr/Jaapproximately represents the inter-block shear strength,andJw/SRFmay be used to describe the active stress.When there are sufficient joint sets to define blocks,together with the presence of excavation for stress release,the roughness of the principal joint sets will play an important role in determining whether overbreak occurs.It is of interest to note thatJrhas been approximately related toJRCand to different scales ofJRCas shown in Fig.23.

Fig.23.Correlation between the joint roughness number Jr and JRC.The JRC20 and JRC100 values were illustrative estimates of the possible scale effect encountered with 20 cm and 100 cm block sizes.The Jr ratings are from the Q-system (Barton,1987).