Integrated percutaneous sclerotherapy and surgical intervention for giant cutaneomucosal venous malformation from TIE2 mutation: A case report

Song Wang, Renrong Lv, Guangqi Xu,*, Ran Huo,*

a Plastic Surgery Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100144, China

b Department of Burn and Plastic Surgery, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan 250021, Shandong, China

Keywords:Cutaneomucosal venous malformations TIE2 mutation Percutaneous sclerotherapy 3D-CTA

A B S T R A C T

1.Introduction

Cutaneomucosal venous malformations (VMCMs)are located within the skin and/or mucosa.These malformations are composed of dilated,serpiginous channels1whose walls feature a thin,flat layer of endothelial cells (ECs), along with scattered, sporadic regions of vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs).2Extracutaneous expression, including the liver,spleen, gastrointestinal tract, and central nervous system, has occasionally been described in familial cases of VMCMs.Most patients with VMCM are born with at least one venous malformation.As the affected individuals age,the lesions present from birth usually become larger,and new lesions often appear.The size, number, and location of venous malformations vary among affected individuals and members of the same family.3

Both sporadic and hereditary forms of VMCMs, inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, have been detailed.The genetic loci responsible for familial VMCMs (OMIM 600195), known as TIE2, have been successfully identified.1,3In this specific case report, we outline patient clinical features, imaging, pathology, treatment process, and insights gathered from family surveys.The patient under consideration bears a giant VMCM in the left pro-axillary region attributed to a TIE2(R849W)mutation.

2.Case presentation

2.1.Clinical findings

A 5-year-old girl presented with a massive congenital VMCM situated in her left axilla.Shortly after her birth,a bluish mass appeared in her left axillary region.When the patient was just 2 months old, she underwent surgery, but a recurrence was observed within one month following the procedure.Subsequently,the size of the lesion increased as she grew older.Clinical examination revealed a sizable area of approximately 18×10 cm2,located on the left pectoralis major region,ipsilateral anterior axilla,and upper arm(Fig.1A).The lesion felt soft upon palpation,and no pulsations were detected.The overlying skin exhibited a bluish-purple hue with a surface resembling cobblestones.No neurological deficits were noted.Paracentesis revealed an abundant accumulation of blood within the lesions(Fig.1B).

Three-dimensional computed tomographic angiography (3D-CTA)images revealed a profuse blood supply in the lesion, with numerous round,oval, and irregular“lipiodol pools”(Fig.1D), as well as multiple phleboliths(Fig.1F)within the affected region.

Given lesion size and propensity of bleeding, an immediate surgical approach was not pursued.Instead,the patient underwent sclerotherapy after being admitted.Pingyangmycin(PYM)percutaneous sclerotherapy(4 mg)was administered once a month for 3 months.The lesion reduced in size, leading to its surgical excision and wound dermatoplasty.Four weeks after the surgery,the lesion recurred and was treated with a 4 mg PYM injection.Subsequent injections were administered every 4 weeks,totaling 2 times(Fig.1C).

2.2.Histopathology

Hematoxylin-and eosin-stained sections displayed irregularly dilated thin-walled venous channels lined by a single layer of ECs.These channels were surrounded by a limited number of delicate smooth muscle fibers and were filled with erythrocytes or thrombi(Fig.1F and 1G).

2.3.Family history

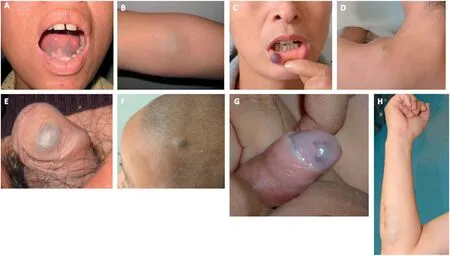

The family history(Fig.2A)unveiled 11 individuals(I1,II2,II4,II9,III4,III10,III11,III23,IV5,IV10,and V17)who were clinically affected.They displayed diverse levels of skin and mucosal engagement (Fig.3).Among these affected members,Individual I1 had passed away,and II2,II4, and II9 declined to be photographed, consequently preventing us from acquiring their images.

2.4.Genetic study

Informed consent was obtained prior to conducting genetic analysis.Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes using commercial kits (PUREGENE® DNA Isolation Kit).All TIE2 exons and their adjacent intronic regions were amplified employing PCR, as previously described.1The amplified fragments were subsequently purified and subjected to bidirectional sequencing.Sequencing was performed utilizing the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems,Foster City,CA,USA)on an ABI Prism 3100 genetic analyzer(Applied Biosystems).The data were then analyzed using sequencing analysis software v5.3.1.

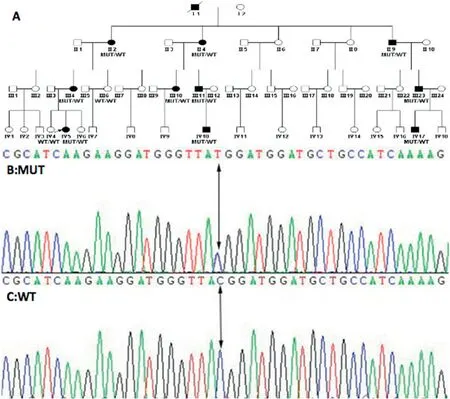

A mutation, namely c.2545T>C, situated within exon 15, was ascertained,resulting in a missense codon alteration(R849W)(Fig.2B).Importantly, this mutation was not discerned in the unaffected family members(Fig.2C).

3.Discussion

Vascular malformations are benign, non-tumorous lesions that are congenital in nature,although they may not become visible until weeks or even months after.4Their incidence is approximately 1.5%, with two-thirds being predominantly venous.5Moreover,they exhibit an even distribution across sexes and races.These malformations are primarily sporadic,known as sporadic venous malformation or VM,although they can also manifest in an autosomal dominantly inherited form.Approximately 1% of venous anomalies manifest as dominantly inherited VMCM.1,3In cases of inherited VMCM, multiple small raised cutaneous lesions are characteristic.Histologically,these lesions consist of enlarged vein-like channels lined by a single layer of ECs,accompanied by regions of surrounding vascular SMC.1,2It is common to observe the presence of oral mucosal lesions and a family history; however, the anomaly can often be asymptomatic.Inherited VMCM is caused by mutations in the EC-specific receptor tyrosine kinase TIE2,also known as TEK,located on chromosome 9p21.Two specific TIE2 mutations, namely R849W and Y897S, both resining within the kinase domain, have been reported.1,6The R849W mutation has been found to heighten the phosphorylation activity of TIE2,resulting in an abnormal ratio of ECs to SMCs in VMCM.7

The diagnosis and differential diagnosis of extensive vascular malformations primarily rely on imaging procedures, such as color Doppler flow imaging, digital subtraction angiography, 3D-CTA, and MRI.In specific scenarios,these imaging techniques not only aid in determining the optimum therapeutic strategy but also constitute an integral component of treatment when involving the administration of embolic or sclerosing agents.A multidisciplinary therapeutic approach is essential for managing VMCMs.Treatment options encompass surgical excision,sclerotherapy,or a combination thereof.4,8Sclerotherapy,while capable of reducing swelling and discomfort, is seldom curative on its own.Conversely,complete surgical excision can be challenging because of the extensive nature of the lesions,risk of bleeding,and possibility of lesion recurrence.Therefore,a hybrid approach of percutaneous sclerotherapy coupled with surgical excision has been employed in our case.

Fig.2.Four-generation family afflicted with cutaneomucosal venous malformations.Solid squares denote individuals affected by the condition.The c.2545T>C(p.R849W) missense mutation is associated with cutaneomucosal venous malformation within this family.MUT, mutation; WT, wild-type.

Fig.3.Composite images of partially affected family members.(A, B) Individual III4, showcasing mucosal involvement of lower lip and sublingual area, along with skin manifestation in the cubital fossa.(C,D)Individual III10,highlighting mucosal changes in the lower lip and skin alterations on the shoulder.(E)Individual III11,presenting mucosal changes in the glans penis.(F)Individual IV10,displaying scalp involvement.(G)Individual IV17,depicting mucosal alterations in the glans penis.(H) Individual III23, demonstrating skin changes on the forearm.

In the present case,the 3D-CTA imagery provided clear insights into the location,dimensions, range,vascular supply,and relationships with adjacent tissues of the substantial VMCM.Within the lesion region,numerous round, oval, or irregular “lipiodol pools” were evident,resulting from the expansion of blood sinus structures and accumulation of blood.The formation of “lipiodol pools” in the 3D-CTA images could be attributed to the extensive dilation of veins within the VMCM,which formed venous sinuses that accumulated blood.Consequently, the successful resection of the substantial VMCM hinged upon effectively managing the potential for significant hemorrhaging during surgery.According to 3D-CTA, it was determined that the lateral thoracic artery supplied the lesion.To ensure a successful surgical outcome, thorough perioperative preparations and the implementation of precise and feasible surgical strategies were pivotal.PYM percutaneous sclerotherapy was performed as a preoperative intervention to minimize lesion size and likelihood of recurrence.However, given the potential for intraoperative hemorrhage,the supplying blood vessels were ligated as far as possible, while ensuring an adequate blood supply for potential transfusions prior to surgery.Additionally, meticulous attention was dedicated to the proper coverage of the surgical wound.In the present case,the preservation of the integrated skin of the lesion proved infeasible owing to the invasion of the dermal layer by the VMCM.To address this challenge, dermatoplasty was performed to effectively manage the situation.

4.Conclusion

In conclusion, the management of large VMCMs is fraught with challenges and risks related to extensive intraoperative hemorrhage and postoperative recurrence.The optimal strategy for addressing these complexities involves a combined approach, integrating percutaneous sclerotherapy with surgical excision.This comprehensive method proves to be the most efficacious for effectively handling large VMCMs and achieving the desired therapeutic outcome.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board of Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University(SWYX:NO.2021–091).Written informed consents were signed by the guardians of the children.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from the guardians of the patient for publication of the data contained within this study.

Authors’ contributions

Wang S: Data curation, Writing-Original draft.Lv R: Visualization,Investigation, Supervision.Xu G: Writing-Review and editing.Huo R:Conceptualization,Methodology,Software.

Declaration of competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(grant no.8187080758).

Chinese Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery2023年3期

Chinese Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery2023年3期

- Chinese Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery的其它文章

- Application of a jigsaw puzzle flap based on free-style perforator to repair large scalp defects after tumor resection: A case series

- Eight-year follow-up on postoperative improvement protocol in extensive metoidioplasty transgenders: A case series

- Absolute ethanol embolization for treatment of peripheral arteriovenous malformations

- Efficacy of tibial transverse transport combined with platelet-rich plasma versus platelet-rich plasma alone in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: A meta-analysis

- Efficacy, effectiveness, and safety of combination laser and tranexamic acid treatment for melasma: A meta-analysis

- A randomized clinical trial assessing the efficacy of single and multiple intralesional collagenase injections for treating contracted scars