PtZn nanoparticles supported on porous nitrogen-doped carbon nanofibers as highly stable electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reaction

Lei Zho ,Jinxi Jing ,Shuho Xio ,Zho Li ,Junjie Wng ,Xinxin Wei ,Qingqun Kong,Jun Song Chen,Rui Wu,*

a School of Materials and Energy,University of Electronic Science and Technology of China,Chengdu,611731,PR China

b Chongqing Medical and Pharmaceutical College,Chongqing,401331,PR China

c Institute for Advanced Study,Chengdu University,Chengdu,610106,PR China

Keywords:PtZn alloy Porous nitrogen-doped carbon nanofibers Electrospinning Oxygen reduction reaction

ABSTRACT The oxygen reduction reaction(ORR)electrocatalytic activity of Pt-based catalysts can be significantly improved by supporting Pt and its alloy nanoparticles (NPs) on a porous carbon support with large surface area.However,such catalysts are often obtained by constructing porous carbon support followed by depositing Pt and its alloy NPs inside the pores,in which the migration and agglomeration of Pt NPs are inevitable under harsh operating conditions owing to the relatively weak interaction between NPs and carbon support.Here we develop a facile electrospinning strategy to in-situ prepare small-sized PtZn NPs supported on porous nitrogen-doped carbon nanofibers.Electrochemical results demonstrate that the as-prepared PtZn alloy catalyst exhibits excellent initial ORR activity with a half-wave potential (E1/2) of 0.911 V versus reversible hydrogen electrode (vs. RHE) and enhanced durability with only decreasing 11 mV after 30,000 potential cycles,compared to a more significant drop of 24 mV in E1/2 of Pt/C catalysts(after 10,000 potential cycling).Such a desirable performance is ascribed to the created triple-phase reaction boundary assisted by the evaporation of Zn and strengthened interaction between nanoparticles and the carbon support,inhibiting the migration and aggregation of NPs during the ORR.

1.Introduction

Proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs) are one of the promising energy conversion devices because of their zero-carbon emission,high energy conversion efficiency and reliability [1–4].To boost the sluggish transfer kinetics of oxygen reduction reaction(ORR),platinum (Pt) and its alloy nanoparticles (NPs) supported on porous carbon are the state-of-the-art catalysts [5–7].However,the high cost and restricted reserves of Pt have greatly hampered extensive commercialization of PEMFCs[8,9].Therefore,developing low-Pt catalysts with enhanced activity and stability is highly desirable for practical application.

To date,numerous studies have demonstrated that Pt and its alloy supported on porous carbon support with large surface area afforded abundant accessible active sites and rapid mass transfer channels,which were of great significance to improve the electrocatalytic activity and utilization rate of Pt [10–13].In general,such catalysts were often obtained by constructing a porous carbon support followed by depositing Pt and its alloy NPs inside the pores[14–16].However,this synthetic route is tedious,time-consuming and often involves harmful chemicals,which are not feasible for large-scale production[17,18].More importantly,the migration and agglomeration of Pt NPs are inevitable under harsh operating conditions owing to the relatively weak interaction between NPs and carbon support [19,20].To address these problems,coating Pt NPs with a protective porous nitrogen-doped carbon(NC)layer derived from polymers such as polyaniline (PANI) or polydopamine (PDA),is a widely studied strategy to inhibit the migration and aggregation of NPs[21–23].However,the thickness of the derived thin NC layer is very challenging to control: if the layer is too thin,it cannot offer a high mechanical strength to immobilize the Pt NPs,while a too thick and dense layer is not beneficial to the exposure of active sites,thus reducing the utilization ratio of Pt catalysts [24,25].As a result,a facile,cost-effective and universal synthetic method is highly desirable to support Pt/Pt alloy NPs on porous carbon support without sacrificing catalytic activity.

Here,we report small-size PtZn NPs supported on porous nitrogendoped carbon nanofibers (denoted as PtZn–PNCNF) through an electrospinning strategy,which is well known to be a facile,economical,and scalable method for the preparation of functional nanomaterials.During the pyrolysis process,Zn salt and ZnO NPs were not only employed as templates to make mesopores at elevated temperatures due to the evaporation of Zn,but also alloy with Pt,thus gaining PtZn alloy catalyst loaded on porous nitrogen-doped carbon (PNCNF).Such a porous structure can guarantee PtZn NPs mostly exposed outside and easily accessed by reactants.In addition,thein-situsynthesized PtZn NPs embedded in the porous carbon gave a strong interaction between the PtZn NPs and the support,preventing the migration and aggregation during both the post-annealing treatment and electrocatalysis process.As a result,the obtained PtZn catalyst perfectly harmonized high catalytic activity and long-term stability,thus exhibiting superior ORR performance compared to commercial Pt/C catalyst.

2.Experimental section

2.1.Synthesis of PtZn–PNCNF

Typically,10 mL of chloroplatinic acid (H2PtCl6) solution (10 mgPtmL-1),2.0 g of polyacrylonitrile (PAN,Mw=150,000),1.0 g of zinc oxide(ZnO)and 1.0 g of zinc acetate(Zn(CH3COO)2)were first dissolved in 15 mL of N,N-dimethylformamide(DMF)and stirred overnight.Then,the obtained solution was then transferred into a 20 mL syringe for electrospinning with a DC voltage of 15 kV and a constant rate of 1.0 mL h-1.The as-spun nanofiber films were stabilized at 220°C for 2 h and subsequently pyrolyzed at 800°C for 2 h under the H2/Ar atmosphere.After that,PtZn–PNCNF catalysts were obtained by HCl (1 M) washing and a post annealing treatment at 800°C for 1 h under Ar atmosphere.For comparison,the synthesis processes of other samples were similar to the PtZn–PNCNF.Pt–NCNF was synthesized just without the addition of ZnO and Zn(CH3COO)2in the precursor.PNCNF was prepared only in the absence of H2PtCl6.

2.2.Characterization

X-ray diffraction (XRD,Bruker,D8 Advancer) was carried out to detect the crystal structure of as-prepared catalysts.The morphology of prepared samples was characterized by scanning electron microscopy(SEM,Phenom) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM,JEM2010F).The chemical state of samples was examined using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) on the equipment of Thermo Fisher Scientific Escalab 250Xi.The Pt content was detected by an Agilent 720 ES inductively coupled plasma(ICP).

2.3.Electrochemical measurements

Typically,2 mg of the samples was dispersed into 800 μL of ethanol and 10 μL of 5 wt% Nafion solution (Dupont) and followed by ultrasonication to form a uniform catalyst ink.Then the ink was pipetted on the working electrode(glassy carbon,5 mm diameter)with a loading of 25 μgPtcm-2for PtZn–PNCNF,Pt–NCNF and commercial Pt/C catalyst(JM,20 wt%),and the loading of PNCNF was 0.5 mg cm-2.The CV was performed from 0.05 V to 1.20 V(vs.RHE)at 50 mV s-1for 60 cycles in nitrogen-saturated 0.1 M HClO4.The LSV curves were recorded in the oxygen-saturated 0.1 M HClO4solution at 10 mV s-1with a rotation speed of 1600 rpm.Carbon monoxide (CO) stripping was conducted in N2-purged 0.1 M HClO4at a sweep rate of 50 mV s-1after being held in CO-saturated 0.1 M HClO4for 20 min.For the MEAs preparation and PEMFC tests,the Pt loading of cathode was 0.10 mgPtcm-2and the commercial Pt/C was 0.10 mgPtcm-2,and the anode was covered by the commercial Pt/C ink with a loading of 0.3 mgPtcm-2on DuPont HP membrane.The MEA was prepared by hot-pressing the cathode and the cell worked at 80°C with a backpressure of 200 kPa.The pure H2and O2were supplied with 100%relative humidity.

3.Results and discussion

The PtZn–PNCNF catalyst was prepared by a facile electrospinning andin-situreduction method(Fig.1).In a typical procedure,a homogeneous solution consisting of chloroplatinic acid (H2PtCl6),zinc oxide(ZnO),zinc acetate (Zn(CH3COO)2),polyacrylonitrile (PAN) and N,Ndimethylformamide (DMF) was firstly electrospun into nanofibers.Subsequently,the as-prepared nanofibers were pre-oxidized and pyrolyzed under H2/Ar atmosphere.The PtZn–PNCNF catalyst was obtained after HCl washing and a second annealing process.During the pyrolysis process,Zn species,i.e.ZnO and Zn(CH3COO)2,act not only as the Zn source to alloy with Pt but also as porogens to generate abundant micro/mesopores.Meanwhile,the Pt precursor in the nanofiber was simultaneously reduced and formed PtZn alloy with Zn sources.In the case of PtZn alloy,more Zn precursor was supplied than that required by PtZn alloy.The evaporation of excessive Zn at a high temperature was used for pore production on the wall of the PNCNF.

Fig.1.Schematic illustration of the preparation of PtZn–PNCNF catalysts.

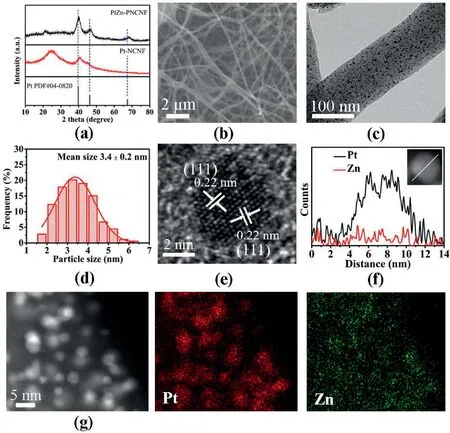

XRD was conducted to characterize the crystal structure of the synthesized catalysts.As shown in Fig.2a,PtZn–PNCNF presented three peaks at about 40.2°,46.7°and 68.4°,corresponding to(111),(200)and(220) planes of Pt,respectively [26].Compared with pure Pt (PDF#04–0802),the diffraction peaks for both PtZn–PNCNF and Pt/NCNF shifted toward a higher angleowing to the incorporation of smaller Zn or N atoms into the Pt lattice,respectively,giving rise to a reduced Pt–Pt spacing [27–29].As a comparison,the corresponding XRD patterns of PNCNF are also displayed in Fig.S1.

Fig.2.(a)XRD patterns of PtZn–PNCNF and Pt–NCNF.(b)SEM,(c)TEM images of PtZn–PNCNF and(d)corresponding histogram of particle size distributions of PtZn NPs.(e) HR-TEM image,(f) EDS line-scanning profile and (g) HAADF-STEM images and corresponding element mapping of PtZn–PNCNF.

The 3D cross-linked carbon nanofiber skeleton of PtZn–PNCNF was shown with a diameter of 100 nm to 200 nm under SEM (Fig.2b) and TEM observations (Fig.2c).The PtZn NPs were evenly dispersed in PNCNFs with an average diameter of 3.4 nm(Fig.2d)and the elemental mapping exhibited the uniform distribution of C,N,Pt and Zn elements(Fig.2a),further confirming no obvious agglomeration of the NPs,which could be attributed to the highly efficient confinement effect of the PNCNFs preventing the movement of these fine NPs.In the highresolution TEM (HR-TEM) image of PtZn–PNCNF,the interplanar spacing of about 0.22 nm was identified,which matched well with the(111) plane of PtZn alloy (Fig.2e) [17,30].Furthermore,as shown in Fig.2f,energy-dispersive spectroscopy(EDS)line-scanning analysis of a NP in PtZn–PNCNF and EDS element mapping of Pt and Zn elements revealed that Zn had been uniformly incorporated into the NP(Fig.2g).The atomic ratio of Pt/Zn in PtZn–PNCNF was 86/14 determined by ICP and the corresponding weight contents of Pt was 16.4%.

Raman spectra of PtZn–PNCNF were taken to gain more insight into the carbon structure and the degree of graphitization (Fig.3a).Two distinct peaks were observed at about 1350 cm-1and 1580 cm-1,which were related to disordered carbon (D band) and graphitic layers (G band),respectively.The calculated intensity ratio of these two bands ID/IGfor PtZn–PNCNF was 0.99,indicating a high degree of graphitization of PNCNFs,which is conductive to improving the chemical stability of PtZn–PNCNF catalyst[31,32].

Fig.3.Characterization results of different samples: (a) Raman spectra,(b) N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms,(c) pore size distributions,(d) XPS survey spectra,high resolution (e) N 1s and (f) Pt 4f spectra.

To investigate the porous structure of these samples,N2adsorptiondesorption analysis was conducted.Compared to Pt–NCNF and PNCNF,an obvious hysteresis loop of type IV isotherm was observed in PtZn–PNCNF,indicating the existence of mesopores (Fib.3b).The specific surface area of PtZn–PNCNF was calculated to be 1098.9 m2g-1,which was much higher than those of Pt–NCNF (403.3 m2g-1) and PNCNF(655.1 m2g-1),indicating that both H2PtCl6and Zn species can promote the formation of porous structure,thus giving rise to the higher specific surface area of PtZn–PNCNF than the Pt-free counterpart PNCNF(Fig.3c).Such a porous structure and high surface area in PtZn–PNCNF were beneficial for the exposure of an increased number of active sites and efficient mass transfer[33,34].

XPS was further performed to identify the surface elemental compositions and the valence states of each sample.The survey spectra for all catalysts are depicted in Fig.3d and relative atomic contents are summarized in Table S1.Encouragingly,the N content of PtZn–PNCNF remained relatively high(>2.5 at%)after carbonization at 800°C,which could modify the active centre of the catalyst and electronic state of carbon support,thus boosting ORR catalytic activity [35,36].The C 1s spectra were deconvoluted into four peaks and attributed to C=C(284.7 eV),C–N (285.5 eV),C–O (286.7 eV) and O–C=O (288.3 eV) (Fig.S3)[37].The existence of C–N bond in the matrix demonstrated that N heteroatoms have been successfully doped into the porous carbon nanofibers [38].The N1s high-resolution spectra of PtZn–PNCNF and Pt–NCNF were further fitted with pyridinic-N (~398.5 eV),Pt–N(~399.2 eV),pyrrolic-N (~400.4 eV) and graphitic-N (~401.3 eV)(Fig.3e) [39].It is noteworthy that both PtZn–PNCNF and Pt–NCNF possess more planar-N (pyridinic and pyrrolic-N) than graphitic-N,and thus can provide more ORR active sites in the acidic medium because of their higher conductivity and the stronger donor-acceptor properties of the former than the latter(Fig.S4)[40–42].Moreover,the deconvoluted Pt–N peak also indicated a strong interaction between Pt and N,which was beneficial to stabilize Pt/PtZn NPs [43].The high-resolution Pt 4f XPS spectra (Fig.3f) of PtZn–PNCNF and commercial Pt/C was deconvoluted into four peaks associated with Pt (0) and Pt (II) [44,45].The peak area of Pt(0)is much larger than that of Pt(II),indicating that Pt in both Pt/C and PtZn–PNCNF is dominantly in the metallic state [46].In addition,the binding energy of Pt 4f in PtZn–PNCNF shifted to lower energy levels than commercial Pt/C catalyst(Fig.3f),suggesting possible electron transfer from Zn to Pt [47].Such a downshift can lower the oxygen adsorption energy,giving rise to an enhanced ORR catalytic activity [48,49].However,the higher binding energy of Pt 4f in Pt–NCNF may also be attributed to the electron transfer from Pt to N because of the lower electronegativity of Pt than N,indicating the strong interaction between Pt NPs and carbon support(Fig.S5) [50].

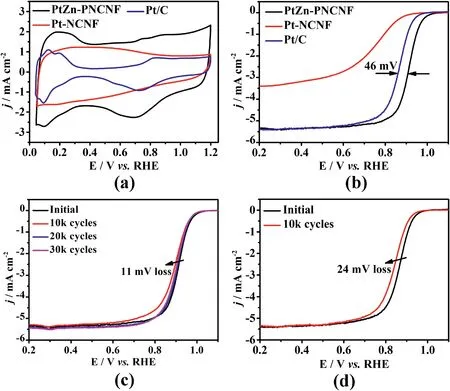

The electrochemical performance of PtZn–PNCNF and other control samples were investigated by cyclic voltammetry(CV)and linear sweep voltammogram(LSV).As displayed in Fig.4a,CV curves of each sample were recorded in N2-purged 0.1 M HClO4solution with a scan rate of 50 mV s-1.Notably,PtZn–PNCNF exhibited a much larger electric double layer region than Pt–NCNF and commercial Pt/C catalyst ascribing to the high surface area of PNCNFs.The electrochemical surface area (ECSA)was then estimated by CO stripping test (ECSACO).The ECSACOof PtZn–PNCNF was 61.4 m2g-1,which is approaching Pt/C(67.4 m2g-1)and much higher than that of Pt–NCNF(9.2 m2g-1)(Fig.S6).The split CO oxidation peaks of PtZn–PNCNF at about 0.8 V (vs.RHE) might be caused by the possible presence of low-coordinated Pt sites [51,52],which could be aroused by acid/electrochemical etching in the acidic medium (Fig.S6) [53].Furthermore,PtZn–PNCNF catalyst showed superior catalytic activity with anE1/2of 0.911 V and onset potential of 1.01 V,which was higher than Pt/C (E1/2=0.865 V,Eonset=0.98 V)(Fig.4b and Table S2).In addition,the smallest Tafel slope of PtZn–PNCNF(57.7 mV dec-1) among these catalysts further verified its faster ORR kinetics(Fig.S7).In comparison,both Pt–NCNF and PNCNF(Fig.S8) exhibited low or almost no activity towards ORR in the acidic medium.For Pt–NCNF,this can be attributed to its low specific surface area and nonporous structure,which made those Pt NPs buried inside the carbon substrate inaccessible for the electrolyte and thus nonfunctional.

Fig.4.(a) CV curves and (b) LSV curves of PtZn–PNCNF,Pt–NCNF and commercial Pt/C catalysts in 0.1 M HClO4 solution.LSV curves of (c) PtZn–PNCNF and (d)commercial Pt/C catalysts before and after ADT.

The ORR stability of these catalysts was further investigated by accelerated durability test(ADT),which involved cycling between 0.6 V and 1.1 V in the O2-saturated 0.1 M HClO4solution(Fig.S9).As depicted in Fig.4c,PtZn–PNCNF presented only 11 mV dropped inE1/2after 30,000 potential cycles.However,the commercial Pt/C suffered from severe degradation with 26 mV decrease inE1/2after only 10,000 potential cycles (Fig.4d).Moreover,the ECSACOof PtZn–PNCNF had a negligible change (6% loss) (Fig.S10a) and the mass activity (MA) of aged PtZn–PNCNF was also largely retained (31.6% loss after 30,000 cycles) compared to Pt/C catalysts (77.4% loss after 10,000 cycles)(Fig.S10b),suggesting the excellent cycling stability of PtZn–PNCNF.It is noteworthy that the obvious deteriorated electrocatalytic activity of PtZn–PNCNF in the first 10,000 potential cycles was mainly due to the leaching of Zn and the dissolution of low-coordinated Pt sites [53,54],which also suppressed the additional CO stripping peak(Fig.S9b)[55].With the continuous CV cycling,the surface of PNCNFs was partially oxidized,and some inner PtZn NPs were exposed,giving rise to a slightly improved catalytic activity in the following 20,000 potential cycles[21].

The surface morphology and structure of PtZn–PNCNF and Pt/C catalysts after ADTs were examined by TEM.As shown in Fig.S11,the Pt NPs in the commercial Pt/C catalyst underwent severe agglomeration with significantly increased average particle size from 2.7 nm to 5.7 nm,and the corrosion of the support can also be identified after only 10,000 potential cycles.On the contrary,the well-defined surface and intact fiber structure of aged PtZn–PNCNF suggested desirable stability of PNCNFs(Figs.S12a and S12b).Furthermore,the loaded PtZn NPs exhibited negligible change in size and no noticeable aggregation was observed(Figs.S12b and S12c).Meanwhile,the lattice spacing of the(111)plane of PtZn alloy after ADT remained as 0.22 nm (Fig.S12d).The above observations indicate that PtZn NPs supported on PNCNF can improve the stability of the catalyst by preventing migration and agglomeration.According to EDS analysis(Figs.S2 and S13),the atom ratio of Pt/Zn in PtZn–PNCNF slightly changed from 91/9 to 95/5 after ADT,indicating the slight etching of Zn during potential cycles.Thus,it can be deduced that the degraded performance of PtZn–PNCNF was mainly caused by the dealloying of PtZn.

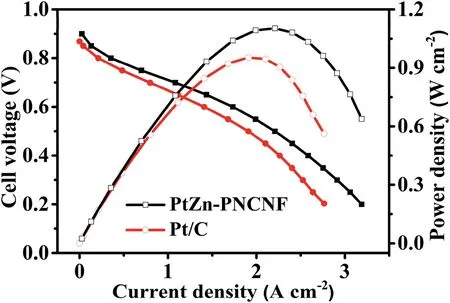

The practical applicability of PtZn–PNCNF was evaluated by fabricating a membrane electrode assembly (MEA).As shown in Fig.5,the open circuit voltage of PtZn–PNCNF was measured to be 0.90 V,which was higher than that of commercial Pt/C catalyst (0.87 V).The polarization curve(i-V)demonstrated that the current density of PtZn–PNCNF was 0.36 A cm-2at 0.8 V,which was superior to commercial Pt/C(0.22 A cm-2at 0.8 V).In addition,the power output of PtZn–PNCNF reached as high as 1.10 W cm-2,which was significantly higher than Pt/C(0.953 W cm-2),suggesting that the PtZn–PNCNF catalyst shows great promise for practical application.

Fig.5.H2–O2 fuel cell i-V polarization (solid symbols and lines) and power density (hollow symbols and dashed lines) plots with the cathode Pt loading of 0.30 mgPt cm-2.

4.Conclusion

In summary,we have successfully prepared PtZn NPs with a size of 3 nm to 4 nm supported in PNCNFsviaan electrospinning strategy for ORR.With a large specific surface area and distinct porous structure,PtZn–PNCNF exhibited much more superior catalytic activity than that of commercial Pt/C catalyst.At the same time,this sample demonstrated a greatly enhanced durability owing to the confinement effect of PNCNFs and strengthened interaction between NPs and support,which can effectively inhibit the migration and agglomeration of PtZn NPs.The maximal power density of PtZn–PNCNF is about 1.2 times that of the commercial Pt/C catalyst,and exhibiting great potential in practical application of H2–O2fuel cell.This work presented a fine controlled synthesis of PtZn alloy with strengthened interfacial interactionviaa facile route,shedding light on the future design of Pt-based electrocatalysts with excellent activity and durability for PEMFCs.

Declaration of competing interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by National Key Research and Development Program(2018YFB1502503).

Appendix A.Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoms.2022.04.001.

- Namo Materials Science的其它文章

- A novel strategy of constructing 2D supramolecular organic framework sensor for the identification of toxic metal ions

- Flexible and electrically robust graphene-based nanocomposite paper with hierarchical microstructures for multifunctional wearable devices

- Piezoresistive behavior of elastomer composites with segregated network of carbon nanostructures and alumina

- Surface reconstruction,modification and functionalization of natural diatomites for miniaturization of shaped heterogeneous catalysts

- DFT study on ORR catalyzed by bimetallic Pt-skin metals over substrates of Ir,Pd and Au

- Constructing P-CoMoO4@NiCoP heterostructure nanoarrays on Ni foam as efficient bifunctional electrocatalysts for overall water splitting