Recent progress in graphene-based wearable piezoresistive sensors: From 1D to 3D device geometries

Ki-Yue Chen ,Yun-Ting Xu ,Yng Zho,* ,Jun-Ki Li ,Xio-Peng Wng ,Ling-Ti Qu

a Key Laboratory of Cluster Science Ministry of Education of China,Beijing Key Laboratory of Photoelectronic/Electrophotonic Conversion Materials,School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering,Beijing Institute of Technology,Beijing,100081,China

b Center for High Pressure Science and Technology Advanced Research,Beijing,100094,China

c Collage of Science,Henan Agricultural University,Zhengzhou,450001,Henan Province,PR,China

d Key Laboratory of Organic Optoelectronics and Molecular Engineering,Ministry of Education,Department of Chemistry Tsinghua University,Beijing,100084,China

Keywords:Piezoresistive sensors Graphene Electronic skin Flexible and wearable devices

ABSTRACT Electronic skin and flexible wearable devices have attracted tremendous attention in the fields of human-machine interaction,energy storage,and intelligent robots.As a prevailing flexible pressure sensor with high performance,the piezoresistive sensor is believed to be one of the fundamental components of intelligent tactile skin.Furthermore,graphene can be used as a building block for highly flexible and wearable piezoresistive sensors owing to its light weight,high electrical conductivity,and excellent mechanical.This review provides a comprehensive summary of recent advances in graphene-based piezoresistive sensors,which we systematically classify as various configurations including one-dimensional fiber,two-dimensional thin film,and threedimensional foam geometries,followed by examples of practical applications for health monitoring,human motion sensing,multifunctional sensing,and system integration.We also present the sensing mechanisms and evaluation parameters of piezoresistive sensors.This review delivers broad insights on existing graphene-based piezoresistive sensors and challenges for the future generation of high-performance,multifunctional sensors in various applications.

1.Introduction

With the rapid development of flexible perceptible electronic devices,wearable physical sensors have attracted tremendous attention in recent years due to their potential utilization in motion detection,artificial intelligence,prosthetic skin,intelligent robots,and human-machine interaction [1–5].In fact,electronic skin can mimic the sensing ability of real human skin and provide wearers with information about their surroundings by relying on multifunction flexible sensors,including pressure and strain sensors,temperature sensors,humidity sensors,as well as other types of sensors[6–10].Wearable pressure(strain)sensors have high sensitivity even under small pressure deformation (<1 KPa)and can even monitor heartbeat and pulse[11].This and other qualities have allowed them to become the preferred subject of physical sensor research in simulating human skin.On the basis of transduction mechanisms,wearable pressure sensors can be classified as either capacitive sensors,triboelectric sensors,piezoelectric sensors,or piezoresistive sensors[12–15].In particular,piezoresistive sensors are regarded as one of the most indispensable pressure sensors since they can convert applied pressure or mechanical force into an electrical signal.This type of sensor also has other advantages such as the fact that it is a simple sensing mechanism,has a robust manufacturing process,consumes low amounts of power,and has potentially-high pixel density and other practical characteristics[16–18].

Traditional piezoresistive sensors usually use a hard substrate such as silicon tablets and/or semiconductors and metal foils as sensing materials,which are cost-effective but have low sensitivity,narrow sensing ranges(0–5%),and are difficult to install in curved or soft surfaces,thus largely limiting their practical applications [19,20].Since the sensing ability of piezoresistive sensors mainly depends on sensitive materials,the microstructure of these sensitive materials,and the supporting substrate,great efforts have been made in nanomaterials to improve sensitivity,detection range,response time,and durability and to achieve high performance in flexible piezoresistive pressure sensors.In recent years,numerous nanomaterials including graphene,carbon nanotubes,carbon black,MXene,metal oxides,metal-organic frameworks,and conductive polymers have been widely applied in various piezoresistive sensor fields[21–25].As a unique two-dimensional (2D) layered material composed of sp2hybrid carbon atoms,graphene in particular has attracted growing attention in piezoresistive sensors due to its superior mechanical properties,simple manufacturing process,and outstanding conductivity(200,000 cm2V-1s-1) [26–28].Moreover,graphene and its derivatives(graphene oxide,(GO))with rich structural forms such as nanoparticles,nanosheets,and nanoribbons can be used as building blocks to combine with other materials,including conducive materials such as polyaniline(PANI),polypyrrole (PPy),MXene,and CNT and insulation materials such as polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS),polyurethane (PU),polyvinyl alcohol (PVA),and nanocellulose that are expected to achieve a high sensitivity and a low detection limit for pressure sensors.

Another important factor that affects sensing performance is the microstructure of the sensitive materials and supporting substrates(usually rubber dielectric layers and polymer membranes),which are closely related to the compressibility of the sensing materials and the contact area between the conducive material and the electrode [29].Researchers have shown that the supporting substrate with microstructures or nanostructure geometry of interlocked microstructures,micro dome arrays,microgrooves,pyramid structures,or wrinkles introduced in pressure sensors can effectively improve their sensitivity[30–33].For example,the sensitivity of a pressure sensor on a flexible substrate with pyramidal microstructure is 50 times higher than that on a planar substrate because the uniform and small pyramidal microstructures can induce large changes in electrical signals under small pressures [34].In addition,the design of the material structure is also an effective way to improve sensing performance,and ways to accomplish this include using a porous structure,wrinkles,or surface roughening[35,36].

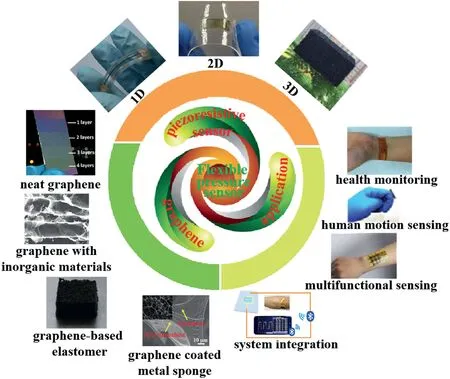

To date,various graphene-based strain and pressure sensors have been assembled and constructed and can be classified according to the micro-dimensions of their piezoresistive sensors: one-dimensional (1D)fiber-like graphene-based sensors,2D planar or thin film graphene-based sensors,and three-dimensional (3D) graphene-based sensors.This classification based on spatial distributions provides an insight into strategies for enhancing sensing performance.The purpose of this review is to summarize recent advances in graphene-based piezoresistive sensors from 1D to 3D device geometries,as shown in Fig.1.

Fig.1.Illustrations of article structure.Graphene-based piezoresistive pressure sensors with 1D,2D and 3D geometries in various application fields.

We first introduce the piezoresistive sensing mechanisms and performance parameters in terms of sensitivity,linearity,response time,recovery time,detection range and durability.After that,we thoroughly discuss the progress of neat graphene,graphene compositing with inorganic materials,graphene-based elastomer (PDMS,PU,eco-flex,etc.),and the graphene coated metal sponge (Cu foam,Ni foam,etc.) used in various dimensional piezoresistive sensors.Next,we present prevailing applications for the graphene-based technology,including health monitoring,human motion sensing,multifunctional sensing,and system integration.Finally,we address challenges and for the future developing practical pressure sensors with excellent comprehensive performance.

2.Piezoresistive sensing mechanisms and evaluation parameters

Pressure sensor devices are used to monitor contact pressure and convert its physical quantity into an electrical signal that can be recorded by an electronic instrument [37].Flexible pressure sensors based on different sensing mechanisms are categorized into four types,as mentioned in introduction.Different from the sensing mechanisms of capacitive pressure sensors,triboelectric sensors,and piezoelectric sensors[29,38],the piezoresistive sensor relies on the conversion of external pressure or strain to a change in electrical resistance.In this section,we discuss the sensing mechanism and evaluation parameters of this type of resistor.

2.1.Piezoresistive sensing mechanisms

In the modern development of pressure sensors,piezoresistive pressure sensors are the most widely used due to their relatively low-cost fabrication process,their specific working mechanism,and their simple signal-collection method [39,40].For graphene-based piezoresistive sensors,the sensing materials based on 1D fiber,2D thin-film,or 3D porous architectures act as a resistor in an electrical circuit by being placed onto or sandwiched between two electrodes.The change in resistance of this type of pressure sensor derives from the deformation of sensing geometry architectures under different external pressures or strains[41,42].When pressure is applied to the sensor,the contact area between the conductive materials and the electrodes increases,thereby greatly reducing electrical resistance in accordance with the improvement of electronic conductivity to benefit from the increase of conductive network path.However,as the tensile length of the sensor increases,the resistance usually also increases due to the reduced conductive path for the strained sensor.In other words,the change in an electrical pathway for current flow induced by the deformable structure of sensing material affects the resistance.

2.2.Evaluation parameters

The performance of piezoresistive sensor can be evaluated by basic parameters such as sensitivity,detection range,linearity,response time,recovery time,and durability to obtain precise information and provide a reference for device design [43,44].Sensitivity is one of the most important parameters of the pressure sensor and is usually defined by the slope of the pressure-response curve,which reflects the accuracy of pressure detection and measurement.The sensitivity of piezoresistive sensors (Sor gauge factor (GF)) is generally denoted by (ΔA/A0)/ΔP,where ΔArepresents the relative change of electrical signals,A0stands for the initial signal value,and ΔPis the variation value of the pressure or strain applied.The formula for calculating piezoresistive and capacitive sensitivity is different from that of a piezoelectricity sensor owing to a non-zero initial signal that occurs in piezoresistive and capacitive sensors.Besides GF,detection range,linearity,response time,recovery time,and durability are all other significant sensing properties.

Detection range is the maximum and minimum pressure range that a pressure sensor can detect.For universal pressure sensors that can detect tiny pressure changes such as a human pulse,and large stresses from various kinds of human motion,a certain trade-off between high sensitivity and wide detection range is required[45].Linearity is an important indicator that describes the static properties of a sensor and is also known as nonlinear error.Here,a smaller value accelerates the processing and fitting of the signal.Response time is the time that the signal reaches stability when external stimuli are applied to a sensor.Conversely,recovery time is the time that the signal returns to its stable state after external stimuli is removed from the sensor.Finally,durability is an index used to judge the service life of a sensor.Typically,the lifetime of graphene-based pressure sensors is limited,which may be overcome through the use of a combination of graphene with other polymers(PAN,PI,PVA,and PVP)or elastomers (PDMS,PU,and Ecoflex) [44,46,47].

3.Graphene-based piezoresistive sensors

Graphene-based materials with rich forms based on surface chemical composition and geometry have been widely used in flexible piezoresistive sensors.In the following section,we discuss the relative performance of graphene-based piezoresistive sensors with various dimensions(1D,2D,3D).Properties of flexible graphene-based pressure and strain sensors with different dimensions are shown in Table 1.

Table 1Summary of graphene-based piezoresistive sensors with different dimensions.

3.1.1D Fibrous graphene-based piezoresistive sensors

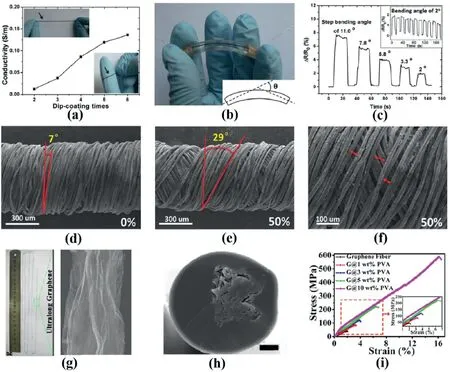

Wearable and flexible electronic devices can capture and monitor various human activities to improve health and even change lifestyles.The application of conventional strain sensors based on metal foils and semiconductors is greatly limited due to their poor flexibility,narrow work range (<5% strain),and very low gauge factor (GF=1 at 30%strain) [74,75].Flexible and lightweight graphene fibers have been preferred as stimulus-sensitive materials for developing flexible piezoresistive sensors,which can integrate the advantages of wearable comfort,good wash fastness,easy integration into clothing,and ability to follow many intricate motions of the human body without limiting the user's movement [76–80].In addition to the properties mentioned above,people are also committed to the research of graphene piezoresistive sensors with high sensitivity,stability,and wide detection ranges.Taking advantage of the flexibility of carbon materials at the nanoscale,Sun et al.designed a graphene-based fiber with “compression spring” architecture,which was composed of a highly elastic polyurethane(PU)core fiber and polyester(PE)fibers that wind around helically with dip-coated graphene [81].The fabricated graphene-based fibers are lightweight,conductive,and can be bent arbitrarily(Fig.2a).To meet detection and practical application requirements,graphene-based fiber was wrapped into a PDMS slab (Fig.2b),and its detection limit was as tiny as 2°(Fig.2c).The authors postulated that the increased gap with the winding angle in PE fiber layers under bending could lead to a decrease of contact area between graphene coated on fibers thus inducing a variable resistance under strain(Fig.2d–f).

Fig.2.(a) Relation curve between dip-coating times of fiber and conductivity.The insets show flexibility of the graphene-based fibers;(b) optical photograph of graphene-based strain sensor;(c)resistance response curve under various bending angels.The inset indicates the cycling test at bending angel of 2° for 10 times;(d–e)SEM images of sensor at 0% strain and 50% strain,respectively;(f) enlarged SEM image of the sensor at 50% strain [81];Copyright © 2015,WILEY-VCH;(g)photograph and SEM image of G@PVA fiber;(h)the section SEM image of the G@PVA fiber;(i)mechanical properties of graphene coated PVA with different amounts of 1,3,5,10 wt% [82];Copyright © 2015,American Chemical Society.

Hu et al.successfully prepared highly stretchable and conductive fibers with a graphene fiber as a core and PVA as a sheath (G@PVA)(Fig.2g–h) in which the graphene fiber was fabricated by using the chemical vapor deposition(CVD)method[82].This porous core-sheath fiber presented a high physical conductivity of 6.6×103S m-1,a tensile strength of 590 MPa,and a strain of 16%due to the high-quality building blocks of graphene and strong bonding between graphene and PVA molecules (Fig.2i).The fiber sensors displayed high strain sensing performance with high sensitivity and cyclic stability.

Inspired by the rolling friction,He et al.prepared novel porous fibers consisting of graphene decorated with polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)nanoballs that presented a globular morphology by a prolonged phaseseparation process (Fig.3a–c) [48].These fiber sensors delivered high gauge factors(51 in 0–5%,87 in 5–8%),a low detection limit(1/10,000 of strain),and long-term durability(more than 6000 times cycles).Finite element simulations(FES)demonstrated that the excellent performance of the as-prepared porous fibers was due to larger structural variations and more conducting network changes between graphene sheets compared with the nanoball-free structure under similar stress(Fig.3d–e).

Fig.3.(a–c)The photo and SEM images of porous graphene fibers.The inset of(c)indicates the average diameter of 117±20 nm for PVDF nanoballs;(d)schematic illustration of the comparison between nanoball-free and nanoball structures by the finite element simulations;(e)illustration of the sensitivity of the porous nanoballdecorated structure[48];Copyright©2019,WILEY-VCH;(f)photo of graphene E-textile sensor as conductive wire;(g)contact angle of pristine textile and graphene E-textile;(h) resistance change of graphene E-textile sensor after water washing [49];Copyright © 2012,Royal Society of Chemistry.

Apart from sensitivity,detection range,stability,and other performance factors,however,comfort is also an important consideration for wearable piezoresistive sensors.Wang et al.fabricated soft,breathable,and water-resistant multimodal pressure sensors by printing and dyeing graphene-based E-textiles to fit with the human body[49].The E-textile exhibited high electrical conductivity (36.2 S m-1),and its water resistance allowed it to be cleaned during daily wear(Fig.3f–h).In addition,the graphene E-textile-based wearable tactile sensors achieved a low detection pressure limit (1.5 Pa) and a fast response time (23 ms).Furthermore,doping metal oxide is also an efficient strategy to produce sensors with high strain and elastic properties.For example,Mao et al.fabricated ferroferric-oxide-grafted graphene that exhibited excellent creep recovery and high strain,nearly nine times that of their original graphene[83].

3.2.2D plane graphene-based piezoresistive sensors

Apart from 1D fiber sensors,2D plane or thin-film-based piezoresistive sensors have also been widely studied due to their high flexibility,low weight,ease of fabrication,and ease of attachment on human skin surfaces.As typical 2D conductive carbon material,graphene can be easily modified and made to function with metal nanowires,other 2D materials,and conducting polymers where it can acquire excellent mechanical elasticity,sensitivity,and high compressibility [22,25,84–87].This has motivated much research on graphene-based piezoresistive sensors,especially for 2D thin-film piezoresistive sensors.For example,Pang et al.successfully designed a mini-size,lightweight graphene film by thein-situchemical reduction method with Vitamin C as a reducing agent [53].The obtained self-supporting film possessed fluctuations on its surface and fluffy layered structures and was directly used as a sensing material.Their results indicated that the sensor could deliver an extraordinarily ultra-wide operation range (0–200kPa) and excellent durability at least up to 150,000 cycles.

Similarly,Zhu et al.synthesized graphene-woven fabrics by directly growing graphene on copper mesh with CVD technology,followed by etching it off by FeCl3and HCl aqueous solution (Fig.4a–b) [88].However,when applying tiny strains and vibrations,a high density of random cracks appeared in the network of the fabricated sensor,which would destroy the conducive path and increase the resistance.In order to improve sensitivity,Chen et al.fabricated micro-structured graphene arrays on a pyramid micro-structured PDMS surface using the layer-by-layer (LbL) method [89].This structure provided a larger contact area than the common-planed graphene film but was prone to deform mechanically when extra pressure was applied.As a result,an ultra-fast response time(0.2 ms)and a very low detection limit of 1.5 Pa were achieved for the micro-structured graphene-based piezoresistive sensors(Fig.4c–d).In addition to this,an assembly based on capillarity is also an effective technique to fabricate high-performance pressure sensors.Tao et al.applied a simple method by soaking tissue paper into GO solution followed by thermal reduction [55].Here,different layers of pressure sensors showed significant differences in sensitivity due to the existence of air gaps between different layers (Fig.4e–f).Their experimental results demonstrated that the eight-layer pressure sensor showed the highest sensitivity.

Fig.4.(a)Photograph of the graphene-based strain sensor film;(b)SEM image of graphene woven fabric[88];Copyright©2015,TSINGHUA UNIV;(c)response time of the micro-structured graphene films.The inset is an enlarged view of the dotted line;(d)tiny pressures of the micro-structured graphene films.The inset shows a staple on the surface of sensor,which corresponds to the application of pressure[89];Copyright©2014,WILEY-VCH;(e)model diagram of multilayer and single-layer paper based pressure sensors;(f) comparison of resistance response of the multilayer model and single-layer model [55];Copyright © 2017,American Chemical Society;(g)sketch map of graphene conductive layers self-attached on micropatterned PDMS elastomer;(h)response curves of graphene conductive film with different layers [11];Copyright © 2019,Elsevier.

A single highly sensitive value seems to be obtained easily,while realization of sensitivity in a wide linearity region for high-performance piezoresistive sensors still presents a great challenge.Chen et al.proposed a solution by regulating the thickness of self-assembled graphene sensing layers [11].They found that the sensitivity of their pressure sensor would increase gradually as the number of graphene conductive layers on the micropatterned PDMS elastomer increased.By contrast,however,its linear range decreased (Fig.4g–h).The sensor with four layers of graphene conductive films exhibited a high sensitivity(1875.53 kPa-1) and a wide linear detection range (0–40 kPa) at the same time,which could be attributed to the appropriate thinner layers' providing highly sensitive properties without losing conductivity.Moreover,their sensor was also used to detect subtle arterial pulse signal information even under the interference of strong body movement in real-time,which had never been achieved before.In addition to the thickness factor of graphene layers’affecting sensor performance,Kong et al.also explored the effects of flake size,out-of-plane resistance,and substrate hydrophilicity of graphene on sensing performance [90].Here,due to the increase in out-of-plane resistance and the uniformity of the graphene film,graphene with smaller flakes and the introduction of surfactant molecules into the graphene ink achieved more reliable pressure response.Additionally,elastic substrate with high reproducibility treated with O2plasma also contributed to an improved gauge factor.

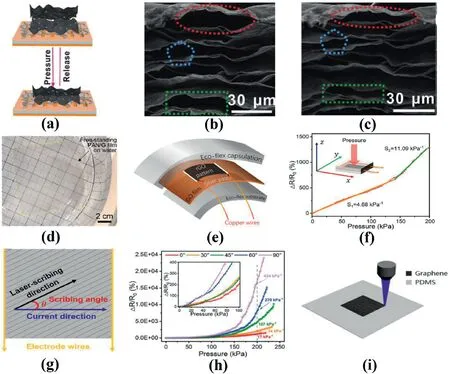

Liu et al.proposed a sandwiched-structured pressure sensor that consisted of wrinkled graphene film and a layer of interconnected PVA nanowires as a scraggly spacer between a pair of interdigital electrodes and sensing material [16].This unique structure exhibited“point-to-point”,“point-to-face”,and “face-to-face” contact modes between wrinkled graphene film and PVA nanowires when applying pressure (Fig.5a).Fig.5b–c revealed the changes of internal structures in graphene film during pressure sensing.At the initial state,the graphene film with a thickness of 80 μm presented a large and loose layer spacing between adjacent graphene sheets(Fig.5b).The layer spacing decreased significantly,however,when the contact area increased after applying pressure on the surface of sensor (Fig.5c).Once pressure was removed though,the internal structures almost recovered to their original state.As a result,the as-prepared pressure sensor delivered a high sensitivity of 28.34 kPa-1and excellent repeatability.

Fig.5.(a)The sensing mechanism of the pressure sensor with sandwiched structure;(b–c)real time layer spacing variation of graphene sheets without(b)and with pressure (c) [16];Copyright © 2018,WILEY-VCH;(d) photograph of transparent PAN/G film on water [94];Copyright © 2019,American Chemical Society;(e)structural diagram of graphene-based sensor by using laser induction method;(f)relative resistance variation of sensor under applied pressure;(g)schematic diagram of laser-scribing angle;(h) resistance change of sensor with various laser scribing angles;the inset is an enlarged image;(i) schematic diagram of laser induced graphene from PDMS [59];Copyright © 2019,American Chemical Society.

Apart from acting as a spacer between sensing materials and conductive electrodes,polymer nanowires can sometimes be used as sensing materials after annealing to further improve the performance of graphene-based pressure sensors.For example,for the transparent graphene-based pressure sensors fabricated by CVD technology,a polymer-assisted transfer process was usually needed to transfer graphene from the growth substrate to the soft and transparent substrate,which caused limited fracture toughness and polymer residues [26,91–93].An annealed polyacrylonitrile nanofiber/graphene (a-PAN/G)composite film transferring to various substrate was successfully designed by Ren et al.that was transfer-medium-free by taking advantage of the cyclization reaction of PAN (Fig.5d) [94].Except for the high transparency (≥94%) under 600 nm illumination,the combination of graphene and annealed PAN fiber network showed a better conductivity and elastic stiffness than pristine graphene sheets.Moreover,this flexible transparent pressure sensor demonstrated a high sensitivity of 44.5 kPa-1and a wide working voltage range from 0.01 to 0.05 V.However,for practical applications,any minor damage from mechanical forces and sunlight would affect the normal function of the sensors.

To solve this matter,Chen et al.introduced TiO2nanocapsules modified with octadecane into graphene sheets,which made graphene easy to disperse in multi-branched polyurethane (PU),thus achieving a multifunctional wearable piezoresistive sensor with thermal insulating,self-healing,and ultraviolet protective features [95].The TiO2nanocapsules in the wearable piezoresistive sensor could not only reflect or absorb UV light but also absorb excess joule heat to avoid scalding the skin of wearers.Owing to the integration of thermal insulating,self-healing and ultraviolet protection,this multi-functional intelligent sensor exhibited typical characteristics similar to natural skin,showing great potential in the application of electronic skin.

In addition,recent research has shown that graphene can be directly produced by using laser ablation on various substrates,such as GO,PI,and PDMS [96–100],which has opened up a new method for manufacturing of sensors.Ren et al.fabricated a graphene-based piezoresistive sensor based on laser-induced graphene using a computer-controlled laser device and achieved over 360,000% in resistance variation and a broad detecting range of up to 200 kPa [96].Interestingly,their triode-mimicking graphene pressure sensor encapsulated in Eco-flex exhibited the positive piezoresistive characteristic in that its sensitivity increased positively with pressure (Fig.5e–f),which was very different from most of the conventional pressure sensors that have a negative correlation between pressure and resistance[22,55].In addition,experimental evidence together with a theoretical model showed that the sensitivity of the pressure sensor with the finer stripe pattern increased with an increase in the scribing-angle,as shown in Fig.5g–h.

Except for GO,many attempts have also been made to fabricate graphene sensing layers using various raw materials including PI and PDMS[101–105].Many research groups have explored sensors similar to those of the laser-induced graphene from GO as sensitive material for piezoresistive sensors.For example,Wang et al.adopted PDMS films as the raw material on which to pattern graphene by direct laser scribing in ambient air(Fig.5i) [59].Two graphene films with the same conductivity were assembled and overlapped face-to-face to form the sensor,which exhibited high sensitivity (~480 kPa-1) and fast response/relaxation time (2 μs/3 μs).Additionally,Ziaie et al.fabricated highly stretchable and sensitive strain sensors based on pyrolyzing conductive carbon patterns on the surface of a polyimide film using a CO2laser device,and the one-step direct laser writing(DLW)method was adopted by Liu and co-workers to fabricate flexible and conductive graphitic porous patterns or arrays from polyimide to create large-scale sensing elements.

3.3.3D graphene-based piezoresistive sensors

To expand the applicability of wearable piezoresistive sensors,many researchers have devoted efforts to the development of 3D graphenebased piezoresistive sensors.Compared to 1D and 2D configurations,3D graphene-based sensing materials with certain geometries offer excellent mechanical elasticity and higher compressibility,which can effectively avoid the collapse of sensing structures during the application of external stimuli [106–110].In many cases,graphene presented in different forms has been extensively investigated in wearable piezoresistive sensors due to its superior electrical and mechanical properties,easy large-scale preparation,and high surface area[111,112].

Generally,3D-conducive graphene networks can be categorized into hydrogel,aerogel,foams,and sponges based on the method of preparation.For example,graphene hydrogels usually obtained through a chemical or hydrothermal method are widely studied for their integration of the dual advantages of good conductivity and 3D network structure that allows for compressibility [113,114].Wu et al.fabricated a conductive hydrogel pressure sensor by combining graphene and PVA with a cross-liked agent of borax [115].Since there were abundant hydrogel bonds,the fabricated pressure sensor exhibited a self-healing ability and showed negligible performance loss after being totally severed,which enabled a repeatable recovery of the electrical response,as depicted in Fig.6a.This exceptional stretchability could remain stable even after cutting and recovery due to the presence of hydrogen-bonding interaction.

Fig.6.(a)Photo and current response of graphene-based PVA hydrogel after robust self-healing process[115];Copyright©2021,WILEY-VCH;(b)schematic diagram of preparation process of 3D MX/rGO aerogel;(c)SEM image of MX/rGO aerogel[116];Copyright©2018,American Chemical Society;(d–f)SEM images of different freeze-drying methods including isotropic-freezing,unidirectional-freezing,and bidirectional-freezing [119];Copyright © 2021,WILEY-VCH;(g) SEM images of wrinkle structure of graphene-nanowalls;(h) structural map of GNWs-based piezoresistive sensor;(i) the response and recovery time curve of pressure sensor;the insets are the enlarged views of the sensor response (upper left) and recovery time (upper right) curves,respectively [120];Copyright © 2021,American Chemical Society.

Aerogel fabricated by the technique of freezing dip coating a template skeleton,is another promising structural form that can be used to fabricate pressure sensors.For example,Gao's group fabricated a highly ordered hierarchical architecture of hybrid 3D MXene/reduced graphene oxide (MX/rGO) aerogel by applying a simple ice-template freezing technique (Fig.6b–c) [116].Because of the advantages of rGO with a large specific surface area and MXene with high conductivity,the obtained sensor delivered a better performance than a single-component sensor,and presented a high sensitivity (22.56 kPa-1) and good stability over 10,000 cycles.

11. The door was not fastened, because the Bears were good Bears, who did nobody any harm, and never suspected that anybody would harm them: The Bears, through their innocence33, become the classic victims of a home intruder. Since they are good, they trust the world at large and neglect locking their door.Return to place in story.

Hybridization based on low-dimensional materials can make the most use of the synergistic effect anticipated from the molecular-level integration of distinctive sensor components [117,118].For graphene aerogel,due to its intrinsic excellent electrical conductivity,it is difficult to induce large resistance changes when a small amount pressure is applied.Therefore,careful structural design is essential in creating useful sensors from this material,and to date,many efforts have been made to improve sensitivity with structural adjustment.Min et al.successfully prepared lamellar graphene aerogels with a special structure through a bidirectional freezing strategy followed by annealing treatment to enhance the sensitivity of the graphene aerogel-based piezoresistive sensors [119].Fig.6d–f displayed SEM images of different freeze-drying methods including isotropic-freezing,unidirectional-freezing,and bidirectional-freezing.Their results showed that the sensing materials fabricated by bidirectional freezing delivered high sensitivity of -3.69 kPa-1with a low detection limit of 0.15 Pa and could also detect a wide bending angle range of 0°–180°with a detection limit of 0.29°.

In addition,Yang et al.fabricated a controllable graphene-nanowalls(GNWs)wrinkle through the thermal wrinkling method[120].As shown in Fig.6g,the wrinkle structure formed conducting holes between the sensing material and the electrode.The longer the wavelength and the greater the amplitude of the wrinkles,the more changes in the contact area occurred when applying pressure.This sensor exhibited high sensitivity of 59.0 kPa-1and a fast response speed of less than 6.9 ms(Fig.6h–i).

Apart from structural configurations,directly introducing other conductive materials is also an important means to improve sensing performance.For example,Guo et al.fabricated an oriented structure of piezoresistive sensors by anchoring polypyrrole (PPy) on the edges of graphene through a facile sol-gel and hydrothermal approach [36].Similarly,Wang et al.introduced polyaniline(PANI)nanoarrays into 3D ordered rGO sponge via interfacial polymerization and hydrothermal self-assembly processes,which provided a wide reliable sensing range up to 10.22 kPa and a high sensitivity of 0.77 KPa-1[121].In addition,Sun et al.designed vanadium nitride-graphene (VN-G) architectures to fabricate a pressure sensor through a spray-printing process for perfect skin conformability,which also delivered high sensitivity (40 KPa-1at the range of 2–10 KPa)and outstanding stability.

In order to enhance the flexibility and strength of a 3D graphene skeleton further,one common strategy is to fabricate a sensor with outstanding stability and excellent durability by introducing the PDMS,PI,PU,and other polymers or elastomers into the graphene materials themselves.For example,Park et al.prepared a compressive resistance material based on 2D MXene (Ti3C2Tx) with a 1D nitrogen-doped graphene nanoribbon(N-MX/GNR)that was then coated onto the surface of a 3D open-network porous latex rubber by a dip coating process(Fig.7a)[122].When pressure was applied,the pore structure gradually shrank,resulting in an increase in the contact area between conducive materials and thereby a decrease in resistance.Generally,during cycling tests,conventional sensing materials showed two types of hysteresis behaviors:the relative change in resistance under cyclability and the degree of hysteresis of the loading/unloading curve (Fig.7b).These existence of hysteresis behaviors were ascribed to the formation of defects such as slips,cracks,and delamination within the conductive layer and at the conductive layer/elastomer interface (Fig.7c,top view).In contrast,their as-prepared N-MX/GNR sensor showed ignorable sensing hysteresis(1.33%)(Fig.7c,button view)because of the robust mechanical stability of MXene and nitrogen-doped graphene.As a result,the sensor had high sensitivity and could detect a pressure of 3 Pa.Moreover,when applying a constant pressure of 90 kPa,the fabricated sensor could clearly distinguish the signal change caused by a nut (1 KPa),as shown in Fig.7d.

Fig.7.(a)Diagrammatic sketch of (N-(MX/GNR) pressure sensor;(b)the curves of hysteresis behaviors under cyclability for the conventional sensing materials;(c)the existence state of conventional sensing layer and (N-(MX/GNR) sensing layer after loading/unloading test;(d) the signal change due to varying pressure at different baseline pressures.The insets are resistance variation curves under a pressure of 3 Pa and loading a pressure of 1 KPa at high baseline pressure (90 KPa)[122];Copyright © 2021,American Chemical Society;(e–f) photographs of twisted (e) and folded (f) pressure sensors [66];Copyright © 2018,American Chemical Society;(g)schematic illustrations of the structure of GA/PDMS aerogels induced by the concentration of GO and freezing temperature;(h)gauge factor the influence of the pore-size and pore-wall thickness;(i–j)resistance changes of the GA/PDMS strain sensor under different concentration(i)and temperature(j)[126];Copyright© 2016,American Chemical Society.

A tremendous amount of work has been done using graphene composite with PU elastomer,which is another frequently used elastic material for fabricating 3D graphene-based sensors[123–125].For example,Ma et al.combined synergistic conductive multiwalled carbon nanotubes(MWCNTs),graphene,and porous PU sponges (MWCNT/RGO@PU) by convenient dip-coating LbL electrostatic assembly to create versatile piezoresistive sensors[123].Their sponge sensor created in this manner possessed multiple mechanisms including “disconnect-connect” transition of nanogaps,microcracks and fractured skeletons,and compressive contact of the conductive skeletons,which presented better piezoresistive performance than its competitors.

In addition,Ge et al.successfully prepared the composition of rGO and PI on a flexible sponge[66].Their 3D composite exhibited excellent mechanical properties with reliable repeatability of~9000 cycles,and it could be folded and twisted (Fig.7e–f).Moreover,it also displayed a tunable sensitivity of 0.042–0.152 kPa-1.In addition,Wang et al.explored the effect of the concentration of graphene and specific microstructure in graphene aerogel/PDMS (GA/PDMS) induced by a freezing temperature on the pressure sensors’ sensitivity [126].Their experimental results showed that thicker walls of pores in graphene aerogel/PDMS upon a higher freezing temperature(from 28 μm at-196°C to 350 μm at-120°C)resulted in lower sensitivity.They found that this was due to a relatively slower crystallization rate that gave rise to crystals with larger sizes and the fact that the graphene nanosheets stack together after sublimation of the ice(Fig.7g–h).Additionally,as the GO concentration increased,the size of pores gradually decreased(40 μm at 1.83 mg/mL and 10 μm at 14 mg/mL),which also led to lower sensitivity.As a result,the GA/PDMS strain sensor with an optimum GO concentration(1.83 mg/mL)and temperature(-50°C)exhibited the maximum resistance change upon a 5%maximum strain(Fig.7i–j).

4.Applications

Skin-like wearable devices not only have attracted the most attention from researchers but also have shown great potential in a wide range of applications for human-interactive systems because they can provide the foundation for the realization of the next generation of artificial intelligence.In this section,we summarize progress in applications that focus on health monitoring,human motion sensing,electronic skin,and the field of system integration.

4.1.Health monitoring and human motion sensing

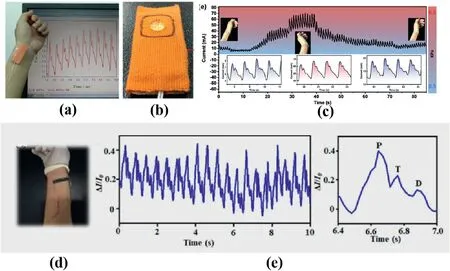

Chen et al.assembled graphene-based pressure sensors in comfortable textiles to monitor pulse waves in a moving state [11].This wearable sensor could be attached around the wrist to detect the arterial pulse and the movement of wrist bending(Fig.8a–c).Fig.8c displayed the change in pulse signal under wrist bending.All signal peaks could be clearly identified by this graphene-based fabric sensor.Similarly,graphene-based pressure sensors were attached onto the skin of the volunteer's wrist to detect electrical signals of the pulse waveform under motion in the study of Wu and Li[127].Heart rate is the rate of contraction of the heart muscle and is an important indicator to assess a person's physical condition.As illustrated in Fig.8d–e,Wu and Li's sensors could accurately detect changes in electrical signals even during running.The radial wave of a single heartbeat including the diastolic(D)wave,tidal(T)wave,and percussion(P) wave were accurately measured by their pressure sensor as well.The shape of the curves was almost similar under motion due to the good flexibility and sensitivity of the sensors.

Fig.8.(a)Arterial pulse signal measured by graphene fabric sensing;(b)the photo of graphene-based fabric sensor;(c)pulse signal of wrist in different bending states.The insets represent the photos of the wrist bending process and their corresponding enlarged current signal [11];Copyright © 2019,Elsevier;(d)photo of pressure sensor attaching on wrist;(e) relative current variation of wrist pulse under running motion state [127];Copyright © 2020,IOP Publishing Ltd.

In addition to physiological signals,other human movements including large-scale motions(running,jumping,and finger,elbow,and wrist movements) and small human movements (eye blinking,cheek bulging,and swallowing)can also be detected by piezoresistive sensors.Large human movements can be>20 KPa,while small motions can be<1 KPa.Thus,an ideal sensor to detect the full gamut of human motion should possess both high sensitivity and a wide detection range.To try to resolve this dilemma,many efforts have been made to develop diverse strategies to fabricate numbers of graphene-based piezoresistive sensors to acquire various pressure signals.Wang et al.designed a Ti3C2Tx/graphene strain sensor to balance the relationship between linearity and sensitivity [97].As illustrated in Fig.9a,human pulses including percussion,tidal,and diastolic peaks were monitored by the flexible strain sensor from the radial artery of wrist.The sensor attached to the human finger and mouth also could detect the bending of a finger from 0°to 90°and the process of opening and closing movements of the mouth(Fig.9b–c).Additionally,the authors attached the sensor to the abdomen and chest to detect different breathing patterns (abdominal breathing,chest breathing,and whole body breathing) during yoga (Fig.9d).Different signal shapes and intensities were clearly recognized.In order to measure the high sensitivity of the sensor further,large movements such as walking and jumping were also measured by attaching the sensor to the knee joint(Fig.9e).

Fig.9.(a)The signs response of wrist pulse detecting by strain sensors sensor attached on the wrist;(b–d) the signs response of finger bending,mouth opening and breathing modes in yoga;the insets show photos of finger at different bending angles;(e) the response curves for detecting walking and jumping [97];Copyright ©2019,Elsevier;(f)a large-area 8-by-8 pressure sensor array;(g)photo of pressure sensor array as a smart seat cushion for posture monitoring[122];Copyright©2019,American Chemical Society;(h) application of the graphene-based sensors attached to different parts including face,mouth,finger,wrist,neck,throat and abdomen for detecting subtle human motions [128];Copyright © 2018,American Chemical Society.

In addition,Lee et al.fabricated a large-area 8-by-8 pressure sensor array to measure the pressure distribution and sitting posture in a smart seat cushion format [122].Fig.9f showed the physical map of their large-area pressure sensor array.The sensor also was highly accurate for distinguishing different seating postures and visualizing pressure sensor data by using a machine learning algorithm(Fig.9g).Additionally,Yang et al.prepared a graphene textile strain sensor to detect various subtle human motions such as finger pulse,wrist pulse,facial expressions,and different breath modes,as shown in Fig.9h[128].These graphene textile sensors were attached on different parts of the body to detect real-time pulse changes.They were able to detect facial expressions of crying and laughing based on relative resistance change versus time and could also accurately monitor pulse shapes and frequency of 70 beats per minute.

4.2.Electronic skin with multifunctional sensing

One critical requirement for flexible and multifunctional E-skins with high tactile sensitivities is the ability to mimic the tactile sensing capabilities of human skin,such as the capabilities to sense static and dynamic pressure,temperature,vibration,and to identify different materials[65,129–131].Sensors with flexibility,high sensitivity,and rapid response properties can act as humanoid robots to manipulate objects and feel the characteristics of living objects,and this may one day imitate and even surpass the human body's somatosensory system.At present,several efforts have been made to explore skin-like multifunctional sensors.

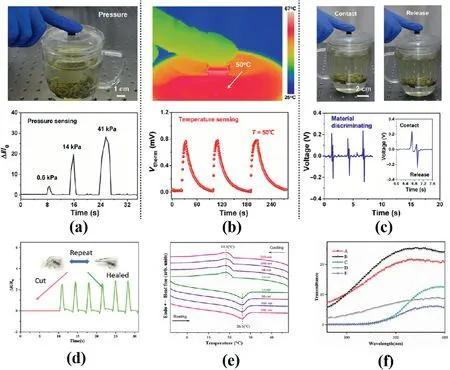

For example,Wang et al.fabricated a self-powered multifunctional Eskin integrated with a triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG) for the simultaneous monitoring of pressure,temperature,and the identification of material [129].A hydrophobic and waterproof polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) film was used as the electrification layer to directly contact the surface of objects and infer material properties based on generated electric signals by virtue of a simple lookup table algorithm operated with MATLAB.They also fabricated a sponge-like deformable E-skin sensitive to varied pressure and temperature via the simple mixed approach with the use of graphene/polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) composite as the thermoelectric material and flexible frame.The E-skin sensor was attached on the finger surface to study pressure and temperature-sensing performance via separately monitoring the obtained current and voltage changes when touching a cup of a hot drink,as depicted in Fig.10a–b.The most attractive feature of this sensor was perhaps its accuracy in material identification.Fig.10c showed the output voltage signals generated by induced electrification responses to a contact-release movement.The fabricated sensor could distinguish ten common flat materials.Perceiving the pressure and temperature of the objects and understanding material properties could help robots or disabled patients to experience the right amount of force and temperature in contact with objects in the real world.

Fig.10.(a–c)Optical images and electrical signs of the sensor attached on the hot drinking for monitoring pressure(a),temperature(b)and materials(c).The inset of(c)is an enlarged view of the signal[129];Copyright©2020,AMER.ASSOC.for the ADVANCEMENT of SCIENCE;(d)the resistance response of the sensor before and after self-healing;(e)differential scanning calorimetry test curves of OTNs under repeated heating and cooling process;(f)UV transmittance of pure cotton fabric A,PU coated cotton fabric B,surface of modified graphene (iaG)/PU coated cotton fabric C,OTNs/PU coated cotton fabric D,OTNs-iaG/PU coated cotton fabric E [95];Copyright © 2021,WILEY-VCH.

Inspired by the structure and function of the human fingertip,Park et al.designed micro-structured ferroelectric skins based on rGO and PVDF composite film as the sensing layer that exhibited piezoresistive and piezoelectric properties simultaneously [65].The flexible and micro-structured ferroelectric skins could detect static/dynamic tactile stimuli including pressure,temperature,and acoustic waves,and were able to distinguish between various surfaces as well.In addition to the imitation of spatiotemporal sensing and the transduction abilities of E-skins,the nature of the sensor itself garnered tremendous interest from the scientific community.Chen et al.fabricated flexible wearable electronics with octadecane loaded titanium dioxide nanocapsule (OTNs)--graphene/PU film (OTNs-iaG/PU) that exhibited self-healing,thermal insulating,and ultraviolet protective properties [95].This wearable sensor showed a good ductility and sensing properties both before and after healing(Fig.10d)due to the self-healing ability of PU with disulfide bonds and the hydrogen bonding.The peaks did not shift after the device was heated and cooled for 20 times,indicative of the good thermal insulation of flexible films(Fig.10e).Furthermore,because the titanium dioxide tended to absorb UV light,the coated fabric performed well as a protectant against UV radiation(Fig.10f).

4.3.System integration

Combining highly sensitive and flexible piezoresistive sensors with energy storage devices,sampling circuits,wireless communication systems,and even machine learning algorithms is regarded as an ideal avenue to realize a proactive,portable,and real-time detection device[19,37,132].However,it still remains a challenge for E-skin to achieve this aspirational application,even when assisted by the advancement of the information processing and related technologies mentioned above.

Wu et al.fabricated a flexible,self-powered sensing system by integrating graphene-based piezoresistive sensors with planar potassium ion micro-supercapacitors (KIMSCs) [115].In this integrated system,the electrochemically exfoliated graphene served as a connecting wire and current collector for both KIMSCs and sensor (Fig.11a).The KIMSC-sensor system could be attached on the finger and elbow to detect bending motion,as shown in Fig.11b–e.In addition,mechanically flexible electronic skin was designed by Liu et al.by integrating an intelligent glove and pressure sensor using GO and graphene as sensing materials,where GO as a surfactant was used to prevent the restacking and aggregation of graphene [133].With the integration of a control system,the pressure sensor attached on the finger surface could manipulate a robot arm to play music by bending different fingers(Fig.12a).

Fig.11.(a) Photo of the integrated KIMSC-sensor system;(b) diagrammatic sketch of integrated system attached on the finger and elbow;(c) photo of hydrogel pressure sensor;(d–e) the signal variation curves of finger bending and elbow bending,respectively [115];Copyright © 2021,WILEY-VCH.

Fig.12.(a) Finger movement stimulation to manipulate a robot arm to play music [133];Copyright © 2017,American Chemical Society;(b–c) weak plus signal monitoring by pressure sensor in real-time whether in the static or dynamic[11];Copyright©2019,Elsevier;(d)a pressure sensing array shoe pad;(e)an integrated gait monitoring system including piezoresistive sensors,power supply unit and terminal device;(f–g)plantar pressure signal and heat maps[96];Copyright©2020,American Chemical Society.

Wearable wireless monitoring systems avoid cumbersome wired transmission and provide convenient and autonomous service for health monitoring.A real-time arterial pulse monitoring prototype has already been realized by integrating a pressure sensor,a custom-built remote transmitter,and a smart phone[11].The designed device could monitor real-time weak pulse signals whether static or dynamic (Fig.12b–c).Similarly,Ren et al.fabricated a pressure sensing array shoe pad with a flexible printed circuit board,as shown in Fig.12d[96].Here,detection of plantar pressure signal when walking was achieved using the wearable gait monitoring system (Fig.12e–f),and the greatest pressure occurred under the calcaneus of the volunteer's foot.At the same time,the sensor under the arch outputted a weak signal for the whole process(Fig.12f).The information presentation form of a heatmap enabled users to perceive the pressure distribution more directly and clearly(Fig.12g).

5.Summary and challenges

We present a comprehensive review in flexible and wearable piezoresistive sensors from 1D,2D,to 3D geometries with graphene and graphene-based composite materials,aiming at structural design of graphene materials,piezoresistive sensing mechanisms,device performance,and advanced application.At present,the mainstream goal of wearable piezoresistive sensors is to become environmentally friendly,flexible,and powerful.Graphene and its derivatives are promising candidates as pressure-sensing materials due to their high conductivity,large ratio surface area,and morphological diversity,and they provide new opportunities for the manufacture and application of flexible piezoresistive sensors.Furthermore,graphene materials are also biocompatible,which we expect to be used for bioabsorbable and multifunctional sensor for pressure,temperature,strain,and motion in animal models in the future.

We can also expect that wearable graphene-based sensors can be installed on clothes or even directly on human skin to monitor human activities in real time,which has greatly aroused the interest of researchers.In addition,graphene-based sensors can also be expected to be used as electronic skin to meet patients’needs for perception of external environment stimulation,and they may also be able to provide disease detection and prevention.With the current continual research on flexible pressure sensors,the sensing performance of graphene materials has already greatly improved,giving rise to the development of more and more applications.

Although graphene-based pressure sensors have broad application prospects,they still face great challenges ahead,including the following.First,because of the limited flexibility and compressibility of graphene materials,elastomers are often incorporated to protect the graphene materials' structures,and this may result in poor comfort in a practical setting.Second,graphene-based piezoresistive sensors have trouble achieving both high sensitivity and broad working ranges simultaneously,which may be due to the finite compressibility of their stable microstructures along with their structures' being prone to collapse collapsing under high pressure,and this is a common problem,whether for 1D fiber,2D thin film,or 3D graphene-based piezoresistive sensors.Moreover,durability,response time,and linearity are important requirements for long-term use of sensors for detecting human motions of both subtle and large scales.However,the optimization of the microstructures of devices,soft acquisition systems,and new algebraic functions between input and output data may be one promising way to solve graphene-based materials’ problems [19].

Third,for the practical application of electronic skin,there is little focus on a complete system with multiple features that include air permeability,self-healing,biocompatibility,and waterproofness.At present,most piezoresistive sensors are merely flexible and possess few if any of these other important qualities.Fourth,seamless integration of graphene-based sensors with energy storage devices,big data,and the internet of things remains a great challenge.Poor electrical and physical connection between the electrode and the sensing layer makes the sensing process layered for the sensor itself while stretched.In addition,the mismatch in mechanical and electrical characteristics and the complicated structure of sensors and signal transmission circuits(such as interconnects,Bluetooth,analog signal,and digital signal conversion components)are obstacles to achieving high performance functionality.

Finally,one very important challenge is to create miniaturized largearea sensor arrays.The preparation of miniaturized sensor arrays usually requires high-end equipment and expert requirements for technicians.Although many efforts have been made to achieve this desired sensor characteristic,slow readout speed,limited spatial resolution,and easy signal crosstalk are still hurdles to be overcome in building a successful large-area sensor array.

Although challenges and problems exist,addressing the above difficulties will help to accelerate the development of high-performance and multimodal graphene-based piezoresistive sensors that can function in a wide range of emerging applications.We expect this review to provide a deeper understanding of graphene-based flexible piezoresistive sensors and move this particular soft electronic device toward future real-world application.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NSFC(22075019,22035005)and the Young Talent Program of Henan Agricultural University(30500601).

- Namo Materials Science的其它文章

- A novel strategy of constructing 2D supramolecular organic framework sensor for the identification of toxic metal ions

- PtZn nanoparticles supported on porous nitrogen-doped carbon nanofibers as highly stable electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reaction

- Flexible and electrically robust graphene-based nanocomposite paper with hierarchical microstructures for multifunctional wearable devices

- Piezoresistive behavior of elastomer composites with segregated network of carbon nanostructures and alumina

- Surface reconstruction,modification and functionalization of natural diatomites for miniaturization of shaped heterogeneous catalysts

- DFT study on ORR catalyzed by bimetallic Pt-skin metals over substrates of Ir,Pd and Au