Gastrointestinal tumors in transplantation: Two case reports and review of literature

Romain Stammler, Dany Anglicheau, Bruno Landi, Tchao Meatchi, Emilia Ragot, Eric Thervet, Hélène Lazareth

Abstract

Key Words: Gastrointestinal stromal tumors; Imatinib mesylate; Transplantation; Kidney transplantation;Proto-oncogene protein c-KIT; Case report

lNTRODUCTlON

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract[1]. GISTs arise from interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC), which are specialized mesenchymal cells located within the muscle of the GI tract. ICC play a critical role in regulating smooth muscle function and GI tract motility[2]. GISTs are mainly located in the stomach (55%) or the small bowel (30%). About 10% to 47% of patients have metastatic disease at diagnosis[3-5]. About 95% of GISTs display positive staining for the receptor tyrosine kinase KIT (or CD117), 75% of these tumors harbor aKITgene mutation and 10% a platelet-derived growth factor receptor A (PDGFRA) gene mutation[6]. Among KIT-negative GISTs, immunohistochemical expression of discovered on GIST-1(DOG-1) was found in 76% of the cases[7]. Consequently, selective tyrosine kinase inhibitors targeting KIT receptor have been used. The first one, imatinib mesylate (Gleevec®; Novartis, Basel, Switzerland),has shown a sustained objective response in a phase III trial among patients with metastatic or unresectable GISTs in immunocompetent patients[8].

In renal transplant recipients (RTRs), an increased risk of cancer has been reported especially for nonmelanoma skin cancer, virus-associated cancer and lymphoproliferative disorders[9]. Currently,malignancy represents a major cause of mortality among RTRs[10]. Nonetheless, only few cases of GIST have been reported among transplant patients. Overall, 8 cases of GIST[11-17] and 2 cases of extra GIST(EGIST)[14,18] have previously been reported in RTRs and respectively 3 cases[19-21] and 1 case[22] in liver transplant recipients.

We report 2 cases of GIST occurring in RTRs and provide a review of the existing literature concerning GIST occurrence in transplant patients.

CASE PRESENTATlON

Chief complaints

Case 1: A 60-year-old Caucasian man without any symptoms.

Case 2: A 56-year-old Caucasian man presented with upper GI hemorrhage.

History of present illness

Case 1: Hepatic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to explore abnormal hepatic tests.MRI revealed a 32 mm spherical tumor of the lesser curvature of the stomach.

Case 2: The upper GI hemorrhage led to gastric endoscopy, which revealed a spherical gastric tumor in the fundus.

History of past illness

Case 1: He had end-stage renal disease with a kidney biopsy compatible with nephronophthisis despite negative screening for mutation in hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 beta (HNF1B) gene. Hemodialysis was initiated in 2016. In October 2019, he received a kidney transplant from a deceased donor. The initial immunosuppressive therapy combined basiliximab, steroids, tacrolimus, and everolimus. Renal function at hospital discharge was 94 µmol/L, (normal range 53 µmol/L to 97 µmol/L). Initial maintenance immunosuppressive therapy associated steroids, tacrolimus, and everolimus. Due to relapsing lymphocele, everolimus was switched to mycophenolate mofetil (MMF). Moreover, a preexisting mild cytolysis and cholestasis worsened after transplantation leading to the discontinuation of cotrimoxazole and MMF, which were replaced by atovaquone and belatacept (NULOJIX®; Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York, NY, United States), respectively.

Case 2: The patient developed end-stage renal disease of unknown origin. He received a kidney transplantation from a deceased donor. Due to preformed donor specific antibodies (anti-Cw15, mean fluorescence intensity of 6130) on the day of transplantation, induction immunosuppressive therapy combined basiliximab, steroids, MMF, cyclosporine, and intravenous immunoglobulins. At 10 d after surgery, a kidney biopsy was performed due to delayed graft function. It revealed acute tubular necrosis associated with possible acute humoral rejection (g1 cpt0 v0 i0 t0 according to Banff’s classification[23,24], C4d immunostaining was negative). A treatment with high dose steroids, five plasma exchanges and rituximab[25] was initiated allowing improvement of renal function with a nadir in serum creatinine level of 170 µmol/L. Maintenance immunosuppressive therapy included steroids,cyclosporine, and MMF.

Personal and family history

Case 1: His other past medical history consisted in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis,and hypertension.

Case 2: The patient had no significant personal or family history.

Physical examination

Case 1: On admission, physical examination was unremarkable.

Case 2: Physical examination was unremarkable except for hematemesis.

Laboratory examinations

Case 1: The patient had mild cytolysis and cholestasis without any other biological abnormality.

Case 2: No abnormal blood test was noticed on admission.

Imaging examinations

Case 1: Body computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed the absence of metastatic dissemination.

Case 2: Body CT scan was consistent with local tumor without metastatic localizations.

Initial diagnosis

Case 1: Upper GI endoscopy found a 3 cm submucosal tumor of the lesser curvature of the stomach.Tumor biopsies were performed using endoscopic ultrasound guidance. Cytological examination revealed spindle-shaped cells that showed positive staining for c-KIT and DOG-1 in immunohistochemistry, confirming the diagnosis of GIST (Figure 1).

Case 2: The gastric endoscopy revealed a spherical gastric tumor in the fundus with a typical macroscopic aspect of GIST.

Initial treatment

Case 1: Partial gastrectomy was performed without complication.

Case 2: Partial gastrectomy was performed.

Course of illness in the hospital

Case 1: No complication associated with the GIST of its treatment was noticed.

Case 2: The patient was rapidly discharged after partial gastrectomy without complication.

FlNAL DlAGNOSlS

Case 1

Histopathology revealed a 27 mm stromal tumor strongly positive for KIT and moderately positive for DOG-1 with a mitotic count of 2 mitosis for 5 mm2. The tumor harbored an exon 11 (p. Val559Ala c.1676T>C)KITmutation[23].

Case 2

Histopathology report described a 51 mm GIST strongly positive for KIT harboring a mitotic count of 10 mitosis for 5 mm2. Of note, an exon 18 D842VPDGFRAmutation was identified.

TREATMENT

Case 1

Regarding the very low risk of progression, no adjuvant therapy was initiated.

Case 2

No adjuvant treatment was initiated at the time of diagnosis.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Case 1

The patient remains in remission at the 1-year follow-up.

Case 2

Two years later, a follow-up MRI revealed hepatic vascular nodules compatible with metastatic lesions.Treatment with imatinib mesylate was initiated. In the absence of a tumor response, imatinib was discontinued 4 mo later and sunitinib (SUTENT©; Bayer, Germany), an anti-angiogenic multikinase inhibitor (anti vascular endothelial growth factor-1, -2, -3, PDGFR-α,-β, c-KIT, fms-like tyrosine kinase 3,and RET) was introduced. Five months later, the onset of thrombopenia, neutropenia, and hepatic cytolysis led to replacement of sunitinib with regorafenib (STIVARGA©; Bayer Pharma AG, Germany),another multikinase inhibitor. Due to side effects and tumor progression, regorafenib was discontinued and dasatinib (SPRYCEL©; Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York, NY, United States) was introduced. Disease progression finally led to stopping all therapies in April 2019. Selective transarterial embolization was performed complicated with artery dissection of the kidney transplant requiring stent implantation. The patient was finally admitted with a clinical presentation of hydrops concomitant with acute renal injury and peritoneal carcinosis. The patient eventually died due to disease progression.

DlSCUSSlON

GISTs represent an uncommon malignant complication of immunosuppression state in solid organ transplantation. We describe 2 cases of typical GIST occurring early in the course of kidney transplantation. The first patient developed an isolated gastric GIST 5 mo after transplantation and the second 4 years after. Both were nonmetastatic at diagnosis although the second patient developedmultiple hepatic metastasis 2 years after complete tumor resection. Of note, the mutation ofPDGFRAD842V in the second case was associated with resistance to imatinib mesylate.

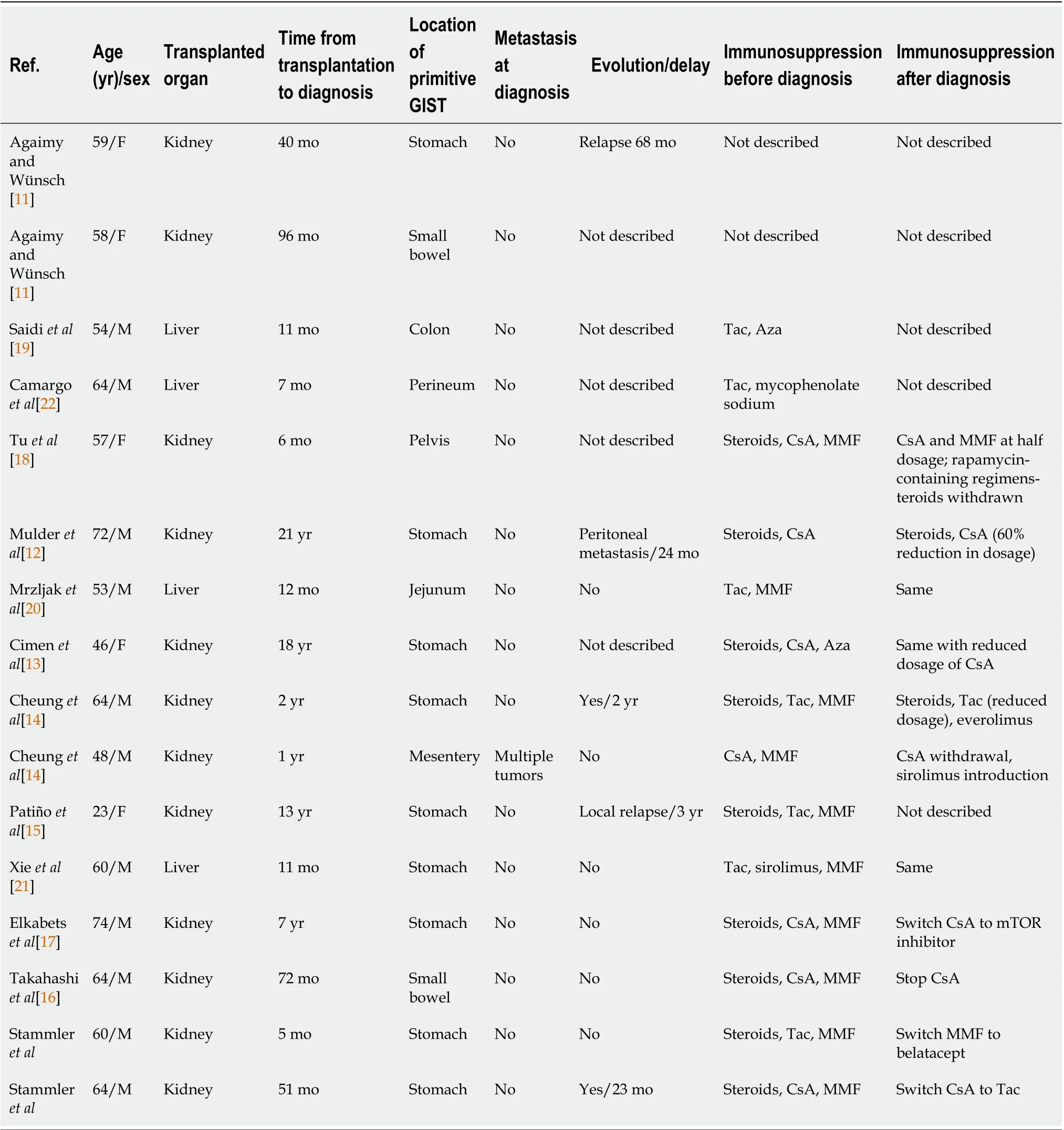

Table 2 Clinical features and immunosuppression regimen of 16 transplant patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor

We looked for previously reported cases of GIST in the literature during the course of transplantation.We searched PubMed and Web of Science databases using the following Medical Subject Headings words: “Gastrointestinal stromal tumors” AND “Kidney transplantation” or “Gastrointestinal stromal tumors” AND “Transplantation.” Using these terms, we found 8 and 31 articles, respectively. Only 12 articles were analyzed. From 2007 to 2020, 14 cases of GIST have been reported in transplant recipients[11-22]. We excluded reports of GIST occurring among nontransplant or bone marrow transplant patients. We also excluded article types different than case reports or case series.

Table 1 summarizes the main features of these patients including the 2 cases described in the present manuscript. Tables 2 and 3 give details on the 14 cases reported. In our literature review, the typical patient profile was a male patient with a median age of 59.5-years-old, who developed large nonmetastatic gastric tumors (median size, 45 mm). The delay between transplantation and diagnosis was highlyvariable, ranging between 5 mo and 21 years. Histopathological data mostly revealed high risk of progression (42.8%) and death occurred in 29% of the cases during follow-up. Surgical treatment was systematically performed if the tumor features were suitable (94%). The use of adjuvant therapy was uncommon (19%).

Table 3 Histopathological features, treatments, and outcome of 16 transplant patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor

Several prognostic classifications have been used to evaluate the risk of recurrence of GIST after surgery. In 2002, Fletcheret al[26] claimed size of the tumor and mitotic count, Miettinen and Lasota[27]in 2006 added tumor location and Joensuuet al[28] in 2012 adjoined rupture of the tumoral capsule and male gender. Heinrichet al[29] demonstrated thatPDGFRAandc-KITwere mutually exclusive protooncogenic mutations with similar biologicals consequences, even if associated with different prognostics. Molecular predictors of response to imatinib have been widely studied. UnderlyingKITorPDGFRAmutations are the strongest predictors of imatinib sensitivity[30]. Mutations directly located in thePDGFRAbinding site of imatinib or inducing variations in tridimensional conformation of the tyrosine kinase receptor and subsequently hiding the binding site, may explain inefficacy of therapy.For instance,KITexon 9 mutation is less sensitive to imatinib andPDFGRAexon 18 D842V mutations is associated with imatinib resistance. Nevertheless, these mutations have been correlated with opposite courses of the disease, indolent forPDFGRAexon 18 D842V mutation but aggressive forKITexon 9 mutation[31]. These data should highlight the importance of molecular biomarkers to evaluate prognosis of GIST or EGIST at diagnosis.

Guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of GIST have recently been published[32].Management of local or locoregional disease should always aim for complete resection whenever possible. Otherwise, neoadjuvant treatment with imatinib for 6 to 12 mo should be used in case of sensitive mutation with an overall response rate of 50%[30]. Moreover, high-risk patients, as previously described, should receive adjuvant imatinib for a duration of 3 years[33]. Imatinib remains the first-line therapy for metastatic GIST. Several other targeted therapies such as sunitinib or regorafenib have emerged as second- or third-line treatment, and more recently avapritinib and ripretinib. Several biomarkers, such asKITorPDGFRAmutations, are used as predictive factors for tumoral response to refine therapeutic strategies[32]. Data are missing concerning the level of tyrosine kinase inhibitors’efficacy in transplanted patients.

Data about the management of immunosuppressive therapy after the diagnosis of GIST are scarce. As both imatinib mesylate and cyclosporin are extensively metabolized by cytochrome P4503A4,interaction occurrence has been documented[12]. Reduction in the dosage of cyclosporin should be performed if this treatment is maintained. Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors (mTORis) have shown antiproliferative properties among transplant patients. Schöffskiet al[34] highlighted the potential efficacy of association of everolimus and imatinib in imatinib-resistant GIST in a phase II trial.Cheunget al[14] reported a case of complete tumoral response with sirolimus in a transplant patient with imatinib-resistant GIST. Among the patients described in Tables 1 and 2, mTORis have been initiated or switched in 4 of them. Three of them were alive and relapse-free at last follow-up and the last patient died from pneumonia 2 years after GIST diagnosis.

This study had several limitations. First, the retrospective analysis of GIST cases impairs the reliability of the data. Very few cases of GIST occurring after solid organ transplantation have been described in the last 15 years reducing the significance of this literature review. Moreover, it was unclear if GIST was ade novofeature in our first patient because of the short delay (5 mo) between transplantation and tumor discovery. Unfortunately, the latest available CT scan was performed 7 years before the transplantation. However, some previous cases reported GIST onset within the 1styear following transplantation[14,18-22].

CONCLUSlON

To conclude, GISTs represent rare but potentially severe malignant complication among transplant patients. Further analysis of prognosis value of new biomarkers should improve therapeutic strategies.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Stammler R and Lazareth H designed the study; Stammler R, Lazareth H, Anglicheau D,Meatchi T, Ragot E, and Thervet E investigated the patients and collected the data; Stammler R, Lazareth H, and Landi B interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript; all authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

lnformed consent statement:Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement:The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement:The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:France

ORClD number:Romain Stammler 0000-0002-0533-5964; Bruno Landi 0000-0002-4841-7919; Hélène Lazareth 0000-0002-1500-3736.

S-Editor:Yan JP

L-Editor:Filipodia

P-Editor:Yan JP

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年34期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年34期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Therapeutic strategies for post-transplant recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Pregnancy and fetal outcomes of chronic hepatitis C mothers with viremia in China

- Spontaneous expulsion of a duodenal lipoma after endoscopic biopsy: A case report

- Trends in hospitalization for alcoholic hepatitis from 2011 to 2017: A USA nationwide study

- Analysis of invasiveness and tumor-associated macrophages infiltration in solid pseudopapillary tumors of pancreas

- lmpact of adalimumab on disease burden in moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis patients: The one-year, real-world UCanADA study