Efficacy of cytapheresis in patients with ulcerative colitis showing insufficient or lost response to biologic therapy

Masahiro Iizuka, Takeshi Etou, Shiho Sagara

Abstract For the optimal management of refractory ulcerative colitis (UC), secondary loss of response (LOR) and primary non-response to biologics is a critical issue. This article aimed to summarize the current literature on the use of cytapheresis (CAP)in patients with UC showing a poor response or LOR to biologics and discuss its advantages and limitations. Further, we summarized the efficacy of CAP in patients with UC showing insufficient response to thiopurines or immunomodulators (IM). Eight studies evaluated the efficacy of CAP in patients with UC with inadequate responses to thiopurines or IM. There were no significant differences in the rate of remission and steroid-free remission between patients exposed or not exposed to thiopurines or IM. Three studies evaluated the efficacy of CAP in patients with UC showing an insufficient response to biologic therapies. Mean remission rates of biologics exposed or unexposed patients were 29.4 % and 44.2%, respectively. Fourteen studies evaluated the efficacy of CAP in combination with biologics in patients with inflammatory bowel disease showing a poor response or LOR to biologics. The rates of remission/response and steroid-free remission in patients with UC ranged 32%-69% (mean: 48.0%, median: 42.9%) and 9%-75% (mean: 40.7%, median: 38%), respectively. CAP had the same effectiveness for remission induction with or without prior failure on thiopurines or IM but showed little benefit in patients with UC refractory to biologics. Although heterogeneity existed in the efficacy of the combination therapy with CAP and biologics, these combination therapies induced clinical remission/response and steroid-free remission in more than 40% of patients with UC refractory to biologics on average. Given the excellent safety profile of CAP, this combination therapy can be an alternative therapeutic strategy for UC refractory to biologics.Extensive prospective studies are needed to understand the efficacy of combination therapy with CAP and biologics.

Key Words: Ulcerative colitis; Inflammatory bowel disease; Cytapheresis; Granulocyte and monocyte adsorptive apheresis; Anti-tumor necrosis factor-α antibody; Combination therapy

lNTRODUCTlON

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) of the colon characterized by a relapsing and remittent course[1,2]. Multiple factors, such as genetic background, environmental and luminal factors, and mucosal immune dysregulation, have been suggested to contribute to UC pathogenesis[1]. Several treatments for UC are available to induce and maintain the clinical remission of the disease. For patients with mild to moderate UC, 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) is generally used, and more than 90% of patients receive 5-ASA within 1 year of diagnosis[3]. Corticosteroids (CSs) are the first-line treatment to induce remission in moderate to severe UC[2]. It was reported that immediate outcomes from CSs were complete remission in 54%, partial remission in 30%, and no response in 16%of patients[4]. Despite the effectiveness of CSs in patients with UC, it has been reported that the rate of steroid dependence was 17%-22% at 1 year following treatment with the initial CS therapy and increased to 38% mostly within 2 years[4-8].

Thiopurines have been conventionally used for the treatment of steroid-dependent UC[9-14]. The rates of the induction of CS-free remission with thiopurines in steroid-dependent patients with UC were reported to be 44% and 53%, respectively[13,14]. However, it has also been reported that thiopurine therapy has failed in approximately 25% of IBD patients within 3 mo after treatment initiation, mostly due to drug intolerance or toxicity[11].

Along with the recent advancements in the treatment for UC, effective treatments, including biologics[anti- tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) antibodies[15-25], anti-integrin monoclonal antibody[26]], Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor[27] and tacrolimus[28,29], have been developed for refractory UC. A metaanalysis showed that anti-TNF-α antibodies had more clinical benefits than placebo as evidenced by the former’s increased frequency of clinical, steroid-free, and endoscopic remission and decreased frequency of colectomy[30]. It has been reported that the rates of induction of steroid-free remission in refractory patients with UC with anti-TNF-α antibodies ranged from 40.0%-76.5%[2,16,18,21,22,24].Vedolizumab (VDZ) is an anti-integrin monoclonal antibody. Studies on VDZ showed that clinical response and remission were achieved in 51% and 30% of patients with UC by week 14, respectively[31]. However, despite the significant efficacy of biologics for UC, secondary loss of response (LOR) is a common clinical problem. It was reported that the rate of LOR to anti-TNF-α antibodies in UC ranged from 23%-46% at 12 mo after anti-TNF-α initiation[32]. It was also reported that the incidence rates of LOR to adalimumab (ADA) and infliximab (IFX) were 58.3% and 59.1% during maintenance therapy,respectively (mean follow-up: 139 and 158.8 wk, respectively)[33]. Recent data from a systematic review showed that the pooled incidence rates of LOR to VDZ were 47.9 and 39.8 per 100 person-years of follow-up among patients with Crohn's disease (CD) and UC, respectively[34]. Considering these results, secondary LOR as well as primary non-response to biologics, are a critical issue for the optimal management of refractory UC. In this context, recent studies have shown the efficacy of use of cytapheresis (CAP) in such patients with UC[35-51].

CAP is a non-pharmacological extracorporeal therapy and has been developed as a treatment for UC[52-58]. CAP is performed using two methods, namely, granulocyte and monocyte adsorptive apheresis(GMA), which uses cellulose acetate beads (Adacolumn, JIMRO Co., Ltd., Takasaki, Japan), and leukocytapheresis (LCAP), which uses polyethylene phthalate fibers (Cellsorba., Asahi Kasei Medical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan)[42,52]. GMA selectively depletes elevated levels of granulocytes and monocytes from the patients’ circulation, but spares most of the lymphocytes[52]. LCAP exerts its anti-inflammatory effects by removing activated leukocytes or platelets from the peripheral blood through extracorporeal circulation[42]. It has been reported that CAP is an effective therapeutic strategy for active refractory UC with fewer adverse effects[52-59]. In addition, it is notable that there have been no reports showing LOR to CAP during the treatment.

As described above, recent studies have shown the efficacy of the use of CAP in patients with UC showing a poor response or LOR to biologics, but the results of these studies have not been summarized to date. The purpose of this article is to summarize the current literature on the use of CAP as an alternative therapeutic strategy for patients with UC showing insufficient response or LOR to biologics and discuss the advantages and limitations of this strategy. We also summarized the efficacy of CAP for patients with UC showing insufficient response to thiopurines or immunomodulators (IM)[36,37,42,58-62].

LlTERATURE SEARCH STRATEGY

Electric search for studies published before December 2021 was performed in the PubMed databases.The search terms used were as follows; ulcerative colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, cytapheresis,GMA, biologics, loss of response, anti-TNF-α antibody, infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab,vedolizumab, ustekinumab, combination therapy, thiopurine, and immunomodulator. Reference lists of all relevant articles were searched for further studies. The search was restricted to articles in the English language and included prospective studies, retrospective studies, case series, case reports, and randomized control studies. Subsequently, we generated a state-of-the-art comprehensive review by summarizing the data on the efficacy of CAP in patients with UC (or IBD) showing insufficient or lost response to biologic therapy, and efficacy of CAP in patients with UC showing insufficient response to thiopurines or IM.

EFFlCACY OF CAP lN PATlENTS WlTH UC SHOWlNG lNSUFFlClENT RESPONSE TO THlOPURlNES OR lM

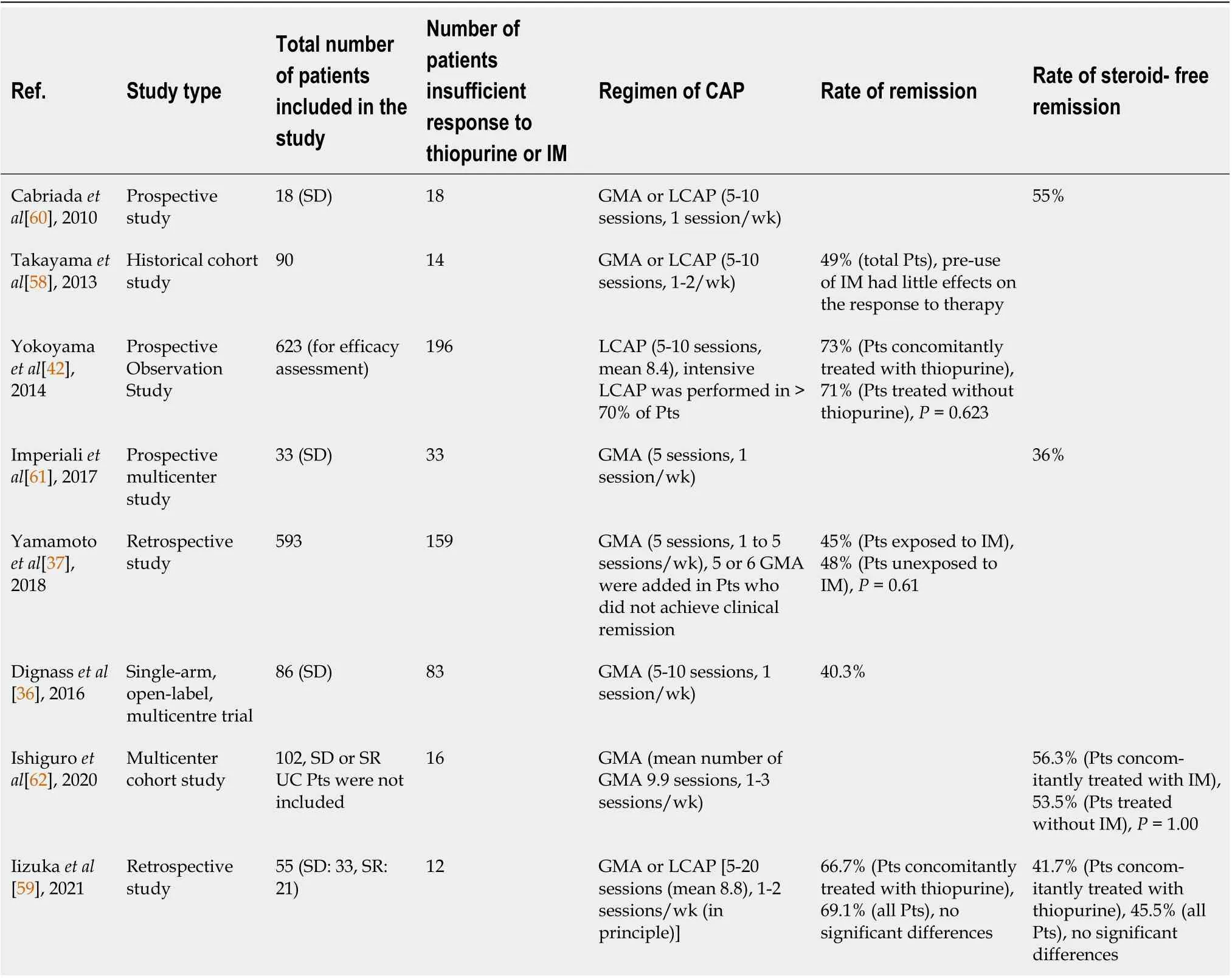

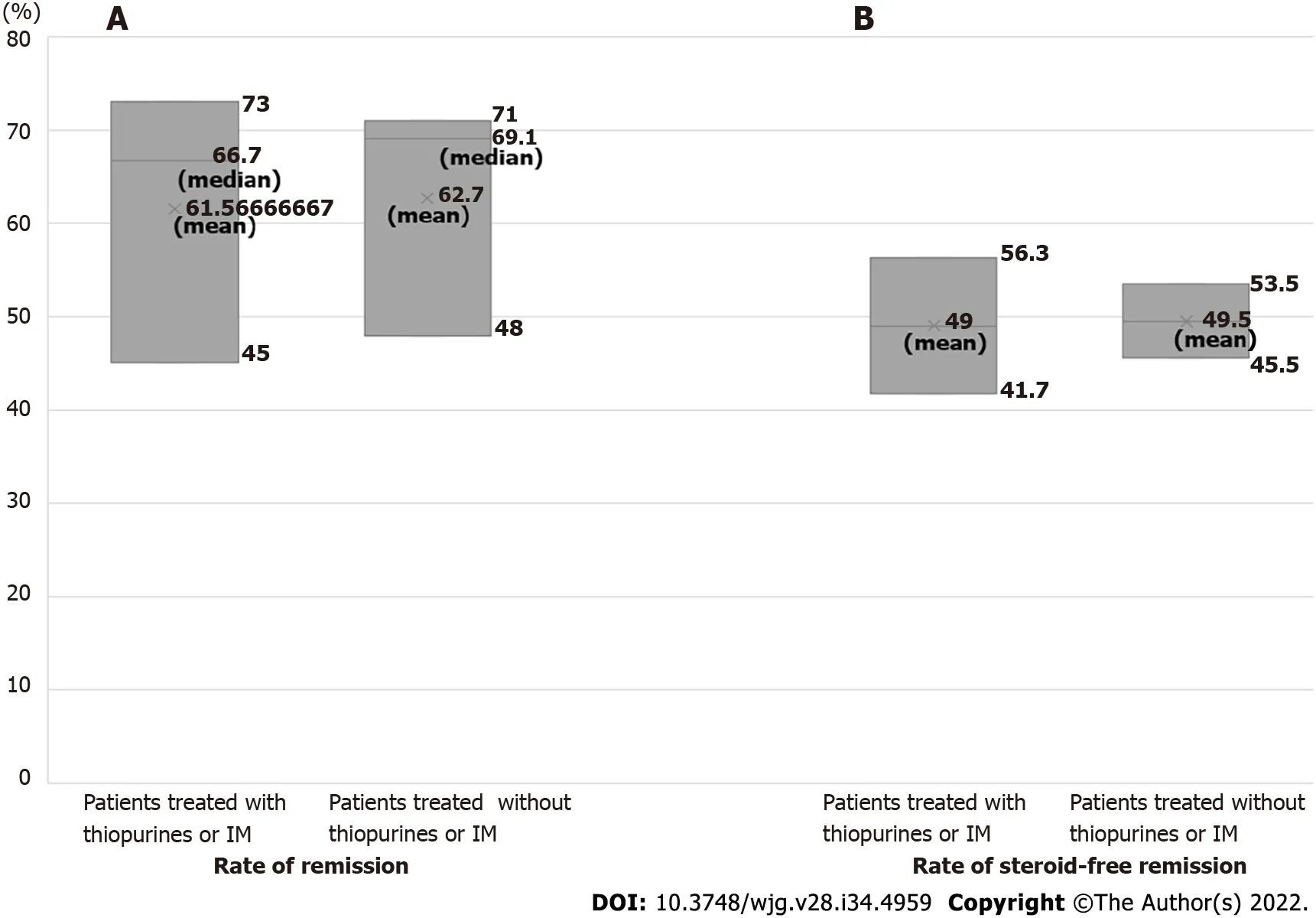

There were eight studies that evaluated the efficacy of CAP in patients having UC with insufficient response to thiopurines (Table 1)[36,37,42,58-62]. These studies include three prospective studies, two retrospective studies, one historical cohort study, one single-arm, open-label, multicentre trial, and one multicenter cohort study. Among them, four studies showed remission rates, and four studies showed steroid-free remission rates in CAP therapy in patients with UC concomitantly treated with thiopurines or IM. Although the background of the patients in these studies were different, the remission rates in CAP therapy ranged from 40.3%-73% (mean ± SD: 56.25 ± 16.03%, median: 55.85%, interquartile range:41.475%-71.425%) and the steroid-free remission rates in CAP therapy ranged from 36%-56.3% (mean ±SD: 47.25 ± 9.99%, median: 48.35%, interquartile range: 37.425%-55.975%) (Figure 1). Among these studies, four[37,42,58,59] compared the rates of clinical remission between the patients exposed to thiopurines or IM and the patients unexposed to them. In all four studies significant differences were not observed in the rates of remission between patients exposed to thiopurines or IM and control. In three of the four studies, the remission rates in patients with UC concomitantly exposed to thiopurines or IM ranged from 45%-73% (mean ± SD: 61.57 ± 14.69%, median: 66.7%), and those in patients unexposed to thiopurines or IM ranged from 48%-71% (mean ± SD: 62.7 ± 12.8%, median: 69.1%)(Figure 2A).

Specifically, Yokoyamaet al[42] used LCAP in their study and demonstrated that the clinical remission rate of the patients concomitantly using thiopurines was 73% and that of the patients without using thiopurines was 71%. They showed that in univariate analysis, concomitant use of thiopurine did not show statistically significant differences between the remission and nonremission groups (P=0.623). Yamamotoet al[37] used GMA in their study and showed that the clinical remission rate of patients exposed to immunosuppressants was 45%, and that of the patients unexposed to immunosuppressants was 48%. They showed that in the univariate analysis, exposure to immunosuppressants did not affect the likelihood of clinical remission in the treatment of GMA (P= 0.61).

Regarding the rate of steroid-free remission, two studies[59,62] compared the rates of steroid-free remission between the patients concomitantly treated with thiopurines or IM and the patients treated without them. These studies showed that significant differences were not observed between the patients concomitantly treated with thiopurines or IM and patients treated without them. The steroid-free remission rates in patients with UC concomitantly treated with thiopurines or IM were 41.7% and 56.3%(mean: 49%) and the rates of steroid-free remission in patients with UC treated without thiopurines or IM were 45.5% and 53.5% (mean: 49.5%), respectively (Figure 2B). Specifically, Ishiguroet al[62] showed that in the univariate analysis, IM therapy was not associated with remission induction rate by GMA (P= 1.00). However, they also showed that in the multivariate analysis, only IM therapy was associated with an increased risk of relapse (OR: 37.6877, 95%CI: 2.4178-587.4632;P= 0.0013).

Table 1 Efficacy of cytapheresis in patients with ulcerative colitis showing insufficient response to thiopurine or immunomodulators

In summary, it was suggested that CAP has the same effectiveness for induction of remission in patients with UC with and without prior failure to thiopurines or IM.

EFFlCACY OF CAP lN PATlENTS WlTH UC SHOWlNG PREVlOUS BlOLOGlCS FAlLURE

Three studies have evaluated the efficacy of CAP in patients with UC showing an insufficient response to anti-TNF-α therapy or exposure to biologics compared with biologic naïve patients with UC[35-37](Table 2). These studies include two retrospective studies and one single-arm open-label multicentre trial. Among these studies, Yamamotoet al[37] showed that the clinical remission rate of the patients exposed to biologics was 31%, and that of the patients unexposed to biologics was 48% (P= 0.01). They showed that in the univariate analysis, biologic naïve patients responded well to GMA (P= 0.01). In multivariate analysis, exposure to biologics was an independent significant factor affecting the clinical efficacy of GMA (P= 0.01). Dignasset al[36] conducted a study on a large cohort of steroid-dependent patients with UC refractory to immunosuppressant and /or biologic treatment to provide additional clinical data regarding the safety and efficacy of Adacalumn (GMA). They showed that remission was achieved at week 12 in 31/77 [40.3% (95%CI: 29.2, 52.1)] of patients who failed on immunosuppressants,10/36 [27.8% (95%CI: 14.2, 45.2)] of patients who failed on anti-TNF-α treatment, and 9/30 [30.0%(95%CI: 14.7, 49.4)] of patients who failed on both immunosuppressants and anti-TNF-αtreatment. Their results suggested that the remission rate using Adacalumn tended to be lower in patients who failed on anti-TNF-α treatment or on both immunosuppressants and anti-TNF-α treatment compared to that of the patients who failed on immunosuppressants. The remission rates in patients with UC exposed to anti-TNF-α treatment in the two studies were 27.8% and 31% (mean: 29.4%), and the remission rates inpatients with UC unexposed to anti-TNF-α treatment were 40.3% and 48% (mean: 44.15%), respectively(Figure 3).

Table 2 Efficacy of cytapheresis in patients with ulcerative colitis showing previous biologics failure

Figure 1 Remission and steroid-free remission rates in cytapheresis therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis concomitantly treated with thiopurines or immunomodulators. Box plot shows that, in cytapheresis therapy, the remission rates range from 40.3%-73% (mean: 56.25%, median: 55.85%,interquartile range: 41.475%-71.425%) and the rates of steroid-free remission range from 36%-56.3% (mean: 47.25%, median: 48.35%, interquartile range: 37.425%-55.975%).

Cabriadaet al[35] conducted a clinical study including 142 steroid-dependent patients with UC[previous thiopurines failure 98 (69%), previous IFX failure 33 (23%)] to evaluate the short and longterm effectiveness and safety of leukocytapheresis therapy by means of a nationwide registry of clinical practice. Although the rate of remission in patients who were refractory to thiopurines or IFX was not described in the paper, no differences in clinical remission were found among those with previous thiopurine or IFX failure.

Figure 2 Remission and steroid-free remission rates in cytapheresis therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis concomitantly treated with thiopurines or immunomodulators and in those treated without thiopurines or immunomodulators. A: Box plot shows that the rates of remission in patients concomitantly treated with thiopurines or immunomodulators (IM) and in those treated without thiopurines or IM range from 45%-73% (mean: 61.57%,median: 66.7%) and 48%-71% (mean: 62.7%, median: 69.1%), respectively; B: The rates of steroid-free remission in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC)concomitantly treated with thiopurines or IM are 41.7% and 56.3% (mean: 49%), and those in patients with UC treated without thiopurines or IM are 45.5% and 53.5%(mean: 49.5%), respectively.

In summary, it is controversial whether CAP has a similar clinical effect in patients with UC who failed biologics treatment and in biologic naïve patients with UC due to limited studies. However, based on these studies, it is suggested that CAP tended to have less efficacy for induction of clinical remission in patients with UC who failed on anti-TNF-α treatment compared to biologic naïve patients with UC.

EFFlCACY OF COMBlNATlON THERAPY WlTH CAP AND BlOLOGlCS lN lBD PATlENTS SHOWlNG lNSUFFlClENT RESPONSE OR LOSS OF RESPONSE TO BlOLOGlCS

Efficacy of the combination therapy with CAP and biologics

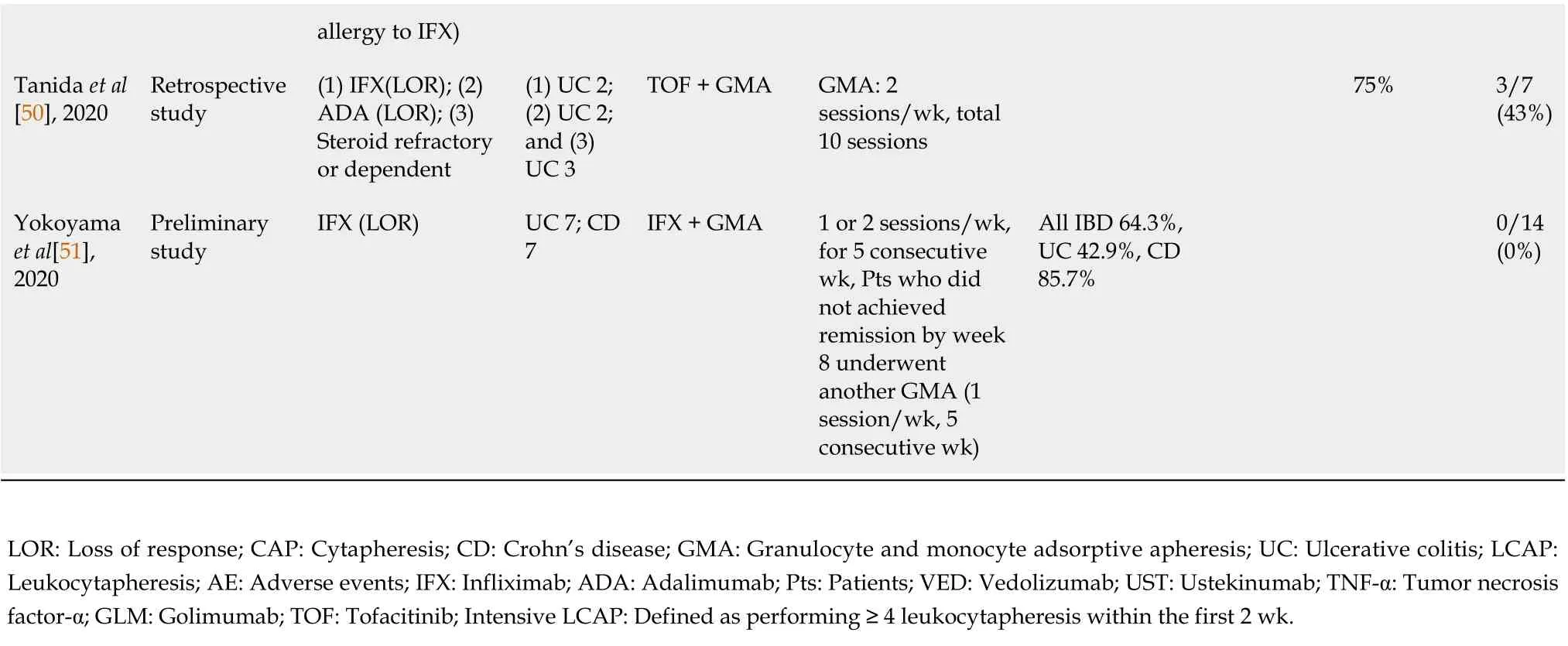

There have been 14 studies that evaluated the efficacy of the combination therapy of CAP and biologics in IBD patients that were refractory to biologics[38-51] (Table 3). These studies include two prospective studies, four retrospective studies, one preliminary study, and seven case reports. These studies include eight studies evaluating combination therapy with GMA or LCAP and anti-TNF-α (IFX: 6 studies; ADA:1 study; IFX, ADA, golimumab: 1 study), four studies with GMA and VDZ, one study with GMA and ustekinumab, and one exceptional study with GMA and a pan-JAK inhibitor tofacitinib. Among these 14 studies, seven studies[42,44,45,47-50] examined the efficacy of combination therapies in patients with UC, five studies[38-41,46] examined its efficacy for CD patients, and two studies[43,51] examined its efficacy for both UC and CD patients.

As shown in Table 3, there were differences in the background of the patients and methods of combination therapies among the studies, and heterogeneity existed in the efficacy of the combination therapies with CAP and biologics among the studies. The rates of remission or response to combination therapies in IBD (UC and CD) patients in these studies excluding seven case reports ranged from 32%-100% (mean ± SD: 62.72 ± 26.65%, median: 57.85%, interquartile range: 40.175%-89.275%) and the rates of steroid-free remission ranged from 9%-75% (mean ± SD: 43 ± 27.4%, median: 44%, interquartile range:16.25%-68.75%), respectively (Figure 4). Regarding the efficacy of the combination therapies in patients with UC, three studies showed the rates of remission or response, and three studies showed steroid-free remission in the combination therapies of CAP and biologics in patients with UC refractory to biologics.The rates of remission or response ranged from 32%-69% (mean ± SD: 47.97 ± 19.0%, median: 42.9%),and the rates of steroid-free remission in patients with UC ranged from 9%-75% (mean ± SD: 40.7 ±33.1%, median: 38%), respectively (Figure 5). On the other hand, the rates of remission or response in CD patients ranged from 46.7%-100% (mean ± SD: 77.5 ± 27.6%, median 85.7%), and the rate of steroidfree remission in CD patients was 50%.

Table 3 Efficacy of combination therapy with cytapheresis and biologics in inflammatory bowel disease patients showing insufficient response or loss of response to biologics

allergy to IFX)Tanida et al[50], 2020 Retrospective study(1) IFX(LOR); (2)ADA (LOR); (3)Steroid refractory or dependent(1) UC 2;(2) UC 2;and (3)UC 3 TOF + GMA GMA: 2 sessions/wk, total 10 sessions 75%3/7(43%)Yokoyama et al[51],2020 Preliminary study IFX (LOR)UC 7; CD 7 IFX + GMA 1 or 2 sessions/wk,for 5 consecutive wk, Pts who did not achieved remission by week 8 underwent another GMA (1 session/wk, 5 consecutive wk)All IBD 64.3%,UC 42.9%, CD 85.7%0/14(0%)LOR: Loss of response; CAP: Cytapheresis; CD: Crohn’s disease; GMA: Granulocyte and monocyte adsorptive apheresis; UC: Ulcerative colitis; LCAP:Leukocytapheresis; AE: Adverse events; IFX: Infliximab; ADA: Adalimumab; Pts: Patients; VED: Vedolizumab; UST: Ustekinumab; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α; GLM: Golimumab; TOF: Tofacitinib; Intensive LCAP: Defined as performing ≥ 4 leukocytapheresis within the first 2 wk.

Regarding the efficacy of the combination therapy, Rodríguez-Lagoet al[47] found no differences in the efficacy depending on the type of anti-TNF received during the combination therapy. They also reported that the response to the combination therapy was inversely proportional to the number of previous anti-TNF agents, but it was not influenced by the presence of primary non-response or secondary LOR. Another important aspect being considered is the regimen of CAP prescribed because an intensified regimen with longer and biweekly sessions has demonstrated rapid and higher efficacy rates without increasing the number of adverse events (AEs)[47,57]. In Table 3, it seems that the studies using a higher frequency of biweekly CAP or intensive CAP tended to demonstrate good clinical efficacy.

Figure 4 Rates of remission or response and steroid-free remission in the combination therapies of cytapheresis and biologics in inflammatory bowel disease patients showing insufficient response or loss of response to biologics. Box plot shows that the remission rates in the combination therapies of cytapheresis and biologics range from 32%-100% (mean: 62.72%, median: 57.85%, interquartile range: 40.175%-89.275%), and the rates of steroid-free remission in the combination therapies range from 9%-75% (mean: 43%, median: 44%, interquartile range: 16.25%-68.75%).

Safety of the combination therapy

One of the strengths of CAP is its safety profile[63]. Of note, several studies have reported the excellent safety of CAP[36,42,52,56,63]. Among these studies, Hibiet al[56] evaluated the safety of Adacolumn in 697 patients with UC in 53 medical institutions. They reported that no serious AEs were observed, and only mild to moderate adverse events were observed in 7.7% of patients. In addition, Motoyaet al[52]showed that the incidence of AEs among elderly patients was similar in all patients. Regarding the safety of the combination therapy with CAP and biologics, eight out of 14 studies listed in Table 3 reported the rate of AEs[39,41,44,46-48,50,51]. Six of the eight studies reported no adverse events. On the other hand, Rodríguez-Lagoet al[47] reported 4% (2/47) AEs related to the technique (anxiety and headache), and Tanidaet al[50] reported 43% (3/7) AEs (one had orolabial herpes, one had a transient increase in creatinine phosphokinase due to intense physical exercise, and one had triglyceride increase). However, Tanidaet al[50] described that AEs observed in their study were consistent with the AEs reported in the oral clinical trials for tofacitinib in ulcerative colitis induction 1 and 2 trials,suggesting that AEs observed in their study were due to AEs from tofacitinib. In summary, AEs were observed in five out of 86 patients (5.8%) in the eight studies.

Based on these results, combination therapy with CAP and biologics is safe and well- tolerated.

Possible mechanisms of the efficacy of the combination therapy with CAP and biologics

Regarding the mechanism of the efficacy of the combination therapy of CAP and biologics, Rodriguez-Largoet al[47] suggested that the benefit may be related to multiple mechanisms of action. They suggested that GMA could reduce the circulating inflammatory burden in addition to direct improvement in disease activity, thus allowing the anti-TNF to restore its response. They also suggested an alternative hypothesis that states that the benefits come from the possible interaction between both treatments. This interaction could be an improvement in blood trough levels of the drug, a reduction of anti-drug antibodies, or both. In this context, several studies supported their hypothesis. Soluble TNF receptors are known to neutralize TNF without invoking a TNF-like response. Saniabadiet al[64]reported that blood levels of soluble TNF-α receptors I and II increased in IBD patients who underwent Adacolumn therapy. Hanaiet al[65] also showed that soluble TNF-α receptor I/II, which are believed to have potent anti-inflammatory actions, were significantly increased in the peripheral blood at the end of the GMA session. Sonoet al[40] showed an increase in plasma IL-10 and a decrease in circulating immune complexes and anti-nuclear antibodies during GMA therapy in GMA-responder CD patients with LOR to IFX. Furthermore, Yokoyamaet al[43] showed that upon GMA therapy, the average plasma trough IFX increased from 0.91 μg/mL to 1.46 μg/mL, with concomitant decreases in C-reactive protein,IL-6, and IL-17A in IBD patients experiencing LOR to IFX. In their recent study, Yokoyamaet al[51]showed that the levels of antibodies to IFX in patients with LOR to IFX were significantly elevated compared with those indicating a sustained clinical remission. They also showed that in patients who received IFX + GMA combination therapy, the IBD symptoms significantly improved together with a decrease in antibodies to IFX. These studies suggest the possibility that GMA therapy can decrease IFX antibodies and increase plasma trough IFX in patients with LOR to IFX.

Figure 5 Rates of remission or response and steroid-free remission in the combination therapies of cytapheresis and biologics in patients with ulcerative colitis showing insufficient response or loss of response to biologics. Box plot shows that the remission rates in the combination therapies of cytapheresis and biologics range from 32%-69% (mean: 47.97%, median: 42.9%), and the rates of steroid-free remission in the combination therapies range from 9%-75% (mean: 40.7%, median: 38%).

Regarding combination therapy with GMA and VDZ, it was hypothesized that this strategy might target the migration of leukocytes into the inflamed tissue by combining their mechanism of action. The peripheral inflammatory cells affected by VDZ may be removed by the ability of GMA to adsorb multiple immune cells[48]. Nakamuraet al[49] also suggested that VDZ and GMA were able to strengthen the suppression of the migration of leukocytes into the inflamed tissue by combining their mechanisms of action. Since the migration of peripheral inflammatory cells from the blood vessels is blocked by VDZ, multiple immune cells-including the congested ones in the peripheral blood- can be removed by GMA. Thus, considering the mechanism of action of GMA and VDZ, it is suggested that this combination therapy can synergically strengthen the therapeutic effects of each therapy.

Summary of the combination therapies with CAP and biologics

In summary, combination therapies of CAP and biologics can safely induce clinical remission or response and steroid-free remission in 32%-100% (mean: 62.72%, median: 57.85%) and 9%-75% (mean:43%, median: 44%) of the IBD patients and in 32%-69% (mean: 47.97%, median: 42.9%) and 9%-75%(mean: 40.7%, median: 38%) of patients with UC refractory to biologics, respectively. In addition, it is a strong point of CAP that there have been no reports showing LOR to CAP during treatment. Given the excellent safety profile of CAP, these results suggest that this combination therapy can be an effective and alternative therapeutic strategy for patients with UC that experienced primary non-response or LOR to biologics. The economic burden of GMA may also be considered in decision-making[63]. A recent study showed that the availability of biosimilars had reduced the costs of anti-TNF agents, but GMA still has a cost slightly below the new biologicals (i.e., ustekinumab and vedolizumab) with an even better safety profile[63]. In this context, Tominagaet al[66] evaluated the efficacy, safety, and treatment cost of prednisolone (PSL) and GMA in 41 patients with active UC who had achieved remission with GMA or with orally administered PSL. They showed that adverse events were reported in 12.5% of the GMA group and 35.3% of the PSL group. The average medical cost was 12739.4€/patient in the GMA group and 8751.3€ in the PSL group (P< 0.05). From these results, they concluded that the higher cost of GMA is offset by its good safety profile.

CONCLUSlON

Summarizing the results of previous studies, it is suggested that CAP has the same effectiveness for induction of remission in patients having UC with or without prior failure of thiopurines or IM. It is controversial whether CAP has a similar clinical effect in patients with UC that failed on previous biologics therapy and in biologic naïve patients. However, it seems that CAP tended to be less effective for induction of clinical remission in patients with UC that were refractory to biologics therapy.Although there was heterogeneity in the efficacy of the combination therapy with CAP and biologics in patients with IBD refractory to biologics, it is notable that combination therapies with CAP and biologics induced clinical remission or response and steroid-free remission in more than 40% of patients with UC that failed on previous biologics therapy on average. Given the excellent safety profile of CAP, it is suggested that this combination therapy can be an alternative therapeutic strategy for patients with UC that were refractory to biologics. However, the number of studies examining this combination therapy has been small and limited to date. Larger prospective studies are needed to better understand the efficacy of the combination therapy of CAP and biologics for refractory patients with UC.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Iizuka M was responsible for the conception and design of the study, literature review and analysis, drafting and critical revision and editing, and final approval of the final version; Etou T and Sagara S was responsible for the critical revision and final approval of the final version.

Conflict-of-interest statement:There is no conflicts of interest associated with any of the senior author or other coauthors contributed their efforts in this manuscript.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Japan

ORClD number:Masahiro Iizuka 0000-0002-4920-2805; Takeshi Etou 0000-0001-8402-7689; Shiho Sagara 0000-0002-1900-7937.

S-Editor:Zhang H

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Zhang H

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年34期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年34期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Therapeutic strategies for post-transplant recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Pregnancy and fetal outcomes of chronic hepatitis C mothers with viremia in China

- Spontaneous expulsion of a duodenal lipoma after endoscopic biopsy: A case report

- Trends in hospitalization for alcoholic hepatitis from 2011 to 2017: A USA nationwide study

- Analysis of invasiveness and tumor-associated macrophages infiltration in solid pseudopapillary tumors of pancreas

- lmpact of adalimumab on disease burden in moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis patients: The one-year, real-world UCanADA study