“与自然共生”:英国儿童游戏场地改造

(英)伍利·海伦(英)索美列斯特-沃德·阿利松(英)布拉德肖·凯特 汤湃

1 背景

1.1 英格兰对儿童户外环境支持政策的变化

签署了《联合国儿童权利公约》[1]的国家长期以来都在以不同的方式维护儿童游戏的权利。以英格兰为例,2008—2010年劳动党政府颁布了《儿童计划》(Children’s Plan)[2]和《游戏策略》(Play Strategy)[3]2项政策来切实保护儿童游戏的权利。其中,《游戏策略》的主要内容为:政府将投入2.35亿英镑(约30亿人民币,按2008年汇率计算)用于全英格兰地区共3 500个自然型儿童游戏场地的新建和传统游戏场地的自然化改造,从而增加儿童与自然接触的机会并提高游戏场地的游戏价值[3]。在过去的50年间,英格兰的儿童游戏场地与世界各地的游戏场地设计思路基本一样,通常采用“组合器械–围栏–地毯”3种元素简单堆砌的形式来布置儿童游戏场地。这种千篇一律的儿童游戏场地在笔者之前的研究中被概括为“KFC”(kit, fence and carpet,即组合器械、围栏、地毯)游戏场地[4]。这种“KFC”游戏场地没有因地制宜地使用自然景观材料,也无法为儿童提供丰富的游戏活动类型,游戏场地的游戏价值[5]没有得到充分挖掘。

为了推动儿童游戏场地改造提升项目在地方层面落实,在《儿童计划》和《游戏策略》的基础上,陆续发布了2份补充文件,分别是《为了游戏而设计》(Design for Play)[6]和《游戏中的风险管理》(Managing Risk in Play Provision)[7]。前者提出了设计儿童游戏场地的10条基本原则,并且列举了大量极具启发性的设计案例;后者在对游戏场地的“安全”“风险”“危害”和“伤害”等相似概念进行明确定义的同时,提出了户外游戏场地风险管控的范围和方式。不仅如此,《游戏中的风险管理》也创新性地提出了“游戏的风险收益分析”(Risk Benefit Analysis)[7]概念,支持在户外游戏场地中保留适当程度的游戏风险,以便让游戏过程更富有挑战,增加户外游戏的趣味性。“游戏的风险收益分析”是通过较为客观的态度看待儿童户外游戏的潜在风险,对游戏趣味性与风险性的对立和统一进行了科学的引导,其核心思想对儿童游戏风险管控政策及法规的制定产生了重要的影响。总体来说,这2份补充文件为地方政府落实儿童游戏场地改造提供了关键的政策说明和实践框架。

然而,2010年英国大选以后,保守党(自由民主党)政府重新执政,政府预算缩减,取消了对儿童户外游戏场地改造提升项目的资助。除了已经投入建设的或者已经签订合同而无法取消的儿童游戏场地项目得以继续建造完成,其他的计划项目都被迫中止。而之前提及的《儿童计划》《游戏策略》以及补充文件《为了游戏而设计》和《游戏中的风险管理》这些关于儿童游戏场地的政策文件也同样被束之高阁。此后,由于政府不再为儿童户外游戏场地建设买单,儿童户外游戏场地的建设或改造只能寄希望于专业设计师自发的热情。然而,即使是从政策支持型转向了自发建设型,优质儿童游戏场地的营造也需要非政府机构提供一定的启动资金。

1.2 与社区合作的工作方式

开展社区合作是20世纪70年代以来英格兰社区规划项目的基本要求之一。在《城镇和乡村计划法(1970年)》中明确规定了规划人员需要与社区居民互动交流。但是,该法案并未对规划人员参与的身份或方式做出具体规定。同样,近些年政府福利彩票基金(National Lottery)发起的基础设施资助项目也明确要求申请人需详细考虑社区的参与方式,并在项目申报中明确描述相关内容。然而,由于缺乏关于社区参与方式的指导,这些项目申请中提及的社区参与方式都比较单一,通常采用社区会议或社区展览的简单方式。这些简单方式在雪莉·阿恩斯坦(Sherry R. Arnstein)1969年所著的《公民阶梯》中被形容为“象征性地参与”[8],即并非真正意义上的参与。

在21世纪初,大乐透福利基金(Big Lottery)对项目申请条件进行了修改,明确了项目不仅要使社区受益,而且要使社区真正地参与到项目中。此外,《儿童计划》项目的资助方Play Builder基金会在后续的资助项目中,也采用社区成员直接参与决定并监督经费支出的方式,来确保社区真正参与到项目中来。然而也有人指出,这些项目执行时间普遍较短,没有足够的时间让居民真正参与进社区的管理和维护中。事实也的确如此,基金资助的大规模建设项目一旦完成,项目中的各个儿童游戏场地的管理和维护只能根据场地情况由场地所有人自行解决。

聚焦于儿童群体,儿童的参与权(儿童参与决策的权力)是《联合国儿童权利公约》(下文简称《公约》)中明确提出的内容。为响应《公约》的倡议,世界各国普遍开展关于儿童参与的研究,但少有研究详细描述由儿童参与所带来的社区长远发展。

基于以上背景,本研究将深入解读于2011—2014年在英格兰北部城市谢菲尔德市开展的“与自然共生”社区儿童游戏场地营造项目,主要描述以儿童为主要参与人群的多样的社区参与型项目的开展方式,以便为社区参与型项目提供更加丰富的参考;同时,也将对儿童参与游戏场地改造项目所带来的积极效果和长远影响进行详细论述,以便推动儿童参与社区环境更新。

2“与自然共生”项目内容

2.1 项目源起与发展

“与自然共生”是一项由“大乐透福利基金社区项目计划”(Big Lottery Reaching Communities)资助的为期3年(2011—2014年)的儿童游戏场地改造项目。其以改善城市公共绿色空间中的儿童户外游戏场地为目标,由谢菲尔德市政管理局的社会福利住房管理部门与福利基金会共同负责开展。谢菲尔德市为占城市人口总量20%的城市低收入人群提供了低廉的福利住房,然而近些年由于政府预算缩减,福利住房社区中用于维护户外游戏场地的资金减少,导致一些儿童户外游戏设备因缺少维护而破损甚至拆除。这样低维护的情况严重影响了户外活动场地质量,居民不再去社区户外活动场地,以致社区户外活动场地闲置、公共绿地浪费、绿地服务效率低下。

“与自然共生”项目的源起可以追溯至2006年,一位谢菲尔德住房管理部门的官员在聆听了笔者关于如何将较低游戏价值的传统“KFC”游戏场地改造成为更具趣味性的自然型游戏场地的讲座以后深受启发,并产生了对谢菲尔德市现存儿童游戏场地进行自然化改造的想法。经过讨论,笔者与该住房管理部门官员均认识到,虽然在谢菲尔德市进行儿童游戏场地的自然化改造的想法具有较高的可行性,但时机并不十分成熟。于是笔者与福利住房管理部门关于儿童游戏和社区环境改造进行了持续的讨论,历经18个月的酝酿与深入探讨以后,儿童游戏场地改造计划重新被正式提上了日程。在这之后,有2件重要的事情也极大地推动了计划的实施。其一是谢菲尔德大学本科学生的设计实践课程选择在福利住房社区进行,让学生有机会在福利住房社区中与居民共度时光并深入了解居民的需求,为社区中儿童游戏场地的优化设计提出了充分依据的同时,也为社区环境提升提供了思路;其二是团队在与谢菲尔德市住房部合作的项目中,制定了整个城市游戏场地的游戏价值提升策略。这个合作项目的成功为后续合作奠定了良好的基础。

2010年,受谢菲尔德大学提供的“知识交流基金”资助,研究团队在第一个社区进行了儿童游戏场地的优化提升设计;后续评估显示,优化设计后的游戏场地的游戏价值得到了显著提升。该项目的成功引起了谢菲尔德和罗瑟勒姆野生动物基金会(Sheffield and Rotherham Wildlife Trust)的关注,该基金会主动提出组建联合团队以共同开展儿童游戏场地提升项目。最后,谢菲尔德住房管理部门、谢菲尔德和罗瑟汉姆野生动物基金会以及谢菲尔德大学三方共同组成联合研究团队,并获得了“大乐透福利基金社区计划”的资助。至此,“与自然共生”项目于2011年7月开始正式执行并在接下来的几年中在谢菲尔德市的24个社区完成了儿童游戏场地自然化改造。

联合研究团队包括了风景园林师、社区活动组织专员、住房管理部门官员、项目经理、项目顾问和项目主要负责人等儿童友好环境从业人员;由谢菲尔德住房管理部门、谢菲尔德和罗瑟汉姆野生动物基金会以及谢菲尔德大学共同负责。此外,谢菲尔德市政部中的住房管理部门和公园乡村管理部门也参与了部分小组会议。项目内容主要包括完成2007年游戏策略项目中遗留下来的游戏场地的改造更新,以及在更多的社区中推进参与型项目实施。至此,“与自然共生”项目不仅完成了中途叫停的游戏策略中的遗留改造项目,而且也推动了更广泛的儿童参与型项目的落地,成为非政府机构对儿童游戏环境改造的示范项目。

“与自然共生”项目实际超额完成了计划目标,参与该项目的组织和机构除了计划书中的所列举的,还包括了租户和居民协会(Tenants and Residents Associations, TARAs)、友邻团体、社区服务中心、社区庇护所和敬老院、残疾人服务机构、流浪人员收容机构、社区野生动物保护机构、片区警察、教堂、社区图书馆、社会福利住房提供机构、城市艺术家和谢菲尔德皇家动物保护协会(Sheffield Royal Society for the Protection of Animals, RSPCA)等,以及托儿所(0~5岁的儿童)、小学(6~10岁的儿童)、中学(11~18岁的儿童)、儿童俱乐部、青年团体、谢菲尔德跑酷小组、流动儿童图书馆和儿童临终关怀中心等与儿童相关的组织,实现了社会范围的联合合作,形成了广泛的社会影响力。

2.2 丰富多样的儿童参与型社区活动

在《游戏策略》补充政策执行期间,全英格兰共有24个社区被列为儿童游戏场地提升项目的示范点。在这24个社区中,研究人员对儿童想如何使用这些活动场地进行了深入了解,以便在设计方案中满足儿童的愿望。项目通常采用非正式观察的方式,观察记录儿童及其他年龄段的社区成员对社区公共场地的使用情况,以实际使用情况为依据决定游戏设备或其他公共设施的设计或布置细节。研究团队也与社区成员就社区的绿色场地和游戏场地的更新计划进行了讨论,更加深入地了解了居民对社区公共空间的使用需求。研究之所以能在社区中顺利展开得益于团队中住房管理部门的工作人员与许多社区居民相熟识。社区居民愿意与研究团队分享观点并接受研究人员的观察。对比之前的社区参与项目中采用的社区会议或展览这些简单的社区参与方式,该项目通过邀请社区中的儿童和成人参与社区发展讨论真正实现了阿因斯坦所描述的更深入层次的社区参与。

根据每个社区的不同情况,研究团队组织了一系列丰富多样的社区活动,以便更好地推进社区参与。在这些丰富的社区活动中,团队中的社区活动组织专员与住房管理部官员通常作为主要组织者全程参与,其他合作伙伴根据自身特色和特长灵活加入。下文将着重列举一些成功举办的特色社区活动,以期为社区参与型活动提供参考,包括:“欢乐日”活动、种植活动、创意活动、趣味运动会、宠物狗展览、“运动日”和“记忆中的街巷”活动。

2.2.1“欢乐日”活动

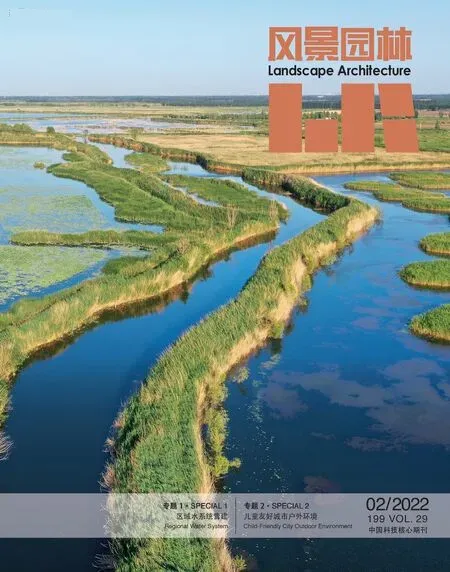

“欢乐日”是每个示范社区开展的第一个活动,为包含儿童在内的社区成员创造了一个走出家门在社区绿色公共空间中与自然接触的机会(图1)。在“欢乐日”活动中,项目团队会正式将更新改造项目的情况介绍给社区儿童和其他年龄段的居民,并与社区居民就场地的未来使用潜能进行初步交流。“欢乐日”活动包含的具体内容主要有:搭建小木屋、武术表演、工艺美术体验、充气城堡、临时沙池、团队游戏和儿童面部彩绘等。在活动场地,团队会为参与活动的社区居民提供一个供应冷热饮品、蛋糕和冰激凌的茶点补给站。这些茶点补给站通常会聚集很高的人气,使社区活动受到更广泛的欢迎。

2.2.2 种植活动

种植活动也是受到普遍欢迎的社区活动之一。在该活动中儿童在社区绿地种植了多种宿根花卉、药用植物、藤蔓植物以及果树,不仅使社区绿地的植物多样性得到了提高,而且也活跃了社区氛围,让儿童真正地参与到社区环境的改造中。在种植活动结束后,孩子们可以把剩下的苗木带回家,种在自家的花园里(图2)。后续研究显示,在24个改造的社区中,种植活动都非常受欢迎。通过植物种植,社区中不同年龄段的人们被联系起来,共同为改变社区环境做出努力。此外,研究团队也通过与社区周围的学校合作来培训专职园丁,以便让学校在社区绿地的后续维护中接管大部分工作。

图2 种植活动中可以让儿童带回家种植的吊篮Hanging baskets to take home

2.2.3 社区创意活动

依据社区的特征来开展创意艺术活动,包括:通过环境艺术、设施、壁画、标志设计和装饰品等元素的置入,临时或永久地改变场地面貌(图3);制作圣诞节提灯并在圣诞游行中进行展示;组织儿童进行石头彩绘、观察鸟类迁徙、设置鸟箱、用树叶制作自然信件、用落叶制作皇冠等活动,鼓励儿童使用自然材料进行手工制作。这些活动几乎都使用了在活动现场收集的或者是从其他地方带来的天然材料。这些社区创意活动吸引了社区中不同年龄段人群的广泛参与。

图3 壁画活动中青少年在墙面上绘画Teenagers painting a mural

此外,作为项目的延伸,团队同样也在部分小学和早教机构中合作开展了一些创意活动。这些创意活动不仅吸引了更多儿童参与,还吸引了一些艺术家参与其中。例如,谢菲尔德市的一个城市艺术团体参与并一同组织了名为“我的生活”的活动。这个艺术团体日常工作内容主要是帮助儿童和青少年发展他们感兴趣的专业艺术技能,例如喷涂艺术、T恤印花和壁画设计等。通过与该深受年轻人喜爱的艺术团体合作,研究小组得以在社区以非正式访谈的方式与年轻人探讨他们对于社区绿地的使用现状和需求。

不仅如此,研究团队还对一所中学的青少年进行了采访,关于他们如何看待他们所生活的社区的户外场所;并且邀请青少年以照片的形式记录社区户外场地中的宏观或微观场景。这些青少年拍摄的照片在社区中进行了展览;团队人员与拍摄照片的青少年探讨了以下问题:1)照片中展示了什么有趣的地方?2)这个地方为什么有趣?3)你和同龄人会如何利用照片中所展示的场地?4)你对于社区公共空间的使用有怎样的想法?5)这些想法能在哪个具体的社区空间得以实现?通过以上问题的探讨,研究团队了解到很多不曾为人所知的青少年关于社区场地使用的想法。

同样,通过利用天然和非天然材料,项目以艺术干预(例如设置临时艺术装置)的方式改变了社区中居民熟悉的场地,有时甚至将居民的活动转变为社区艺术的一部分。例如在一个社区,儿童利用自己设计的服装和艺术品将自己装扮成“活动的雕塑”,并在社区内举办了“雕塑游行”。在这次活动中,虽然临时的雕塑游行道路仅仅存在了短短几个小时,但留下的照片甚至是回忆,足以让孩子们意识到他们的力量也可以让社区空间发生巨大改变,他们也可以对外界环境产生重要影响。

2.2.4 趣味运动会

社区中的趣味运动会包括小木屋建造、定向运动、雕塑步道、复活节彩蛋狩猎、地图测绘和步道建造等。这些多样的活动都有较为灵活的组织形式,甚至在一次社区活动中,有一个小朋友创造性地采用了一种不同寻常的玩法,她带领大家用场地中的“废弃物”搭建了一条道路,这条道路可以让大家从一个游戏器械转移到另一个游戏器械而不触碰地面,她还给这个游戏方式起名为“从这到那”。受到这个小朋友的启发,团队在其他社区的游戏场地也采用了这种游戏方式,这种使用简单材料的创意玩法同样受到其他社区孩子的喜欢。在发现这种不拘一格的充满创意的场地使用的方式会受到孩子们的欢迎以后,团队邀请了专业跑酷团体参与社区活动,他们带领孩子们发现社区户外场地不同寻常的使用方法。随着专业跑酷团体的加入,户外场地中的现有游戏设施、独特地形和其他自然要素都发展出了更加有趣的新玩法。随后,研究团队观察了孩子们使用场地的方式,并以此为基础提出了设计策略,以扩展游戏场地的使用方式,让游戏场地更具挑战性和吸引力。

2.2.5 宠物狗展览

在项目开展的社区之一,户外公共场地大多为遛狗人群使用,因此团队在该社区发起了一次宠物狗展览作为独特的社区活动(图4)。宠物狗展览的目的是用友好的方式让社区中遛狗的居民了解场地将要发生的改造,以及知道即使社区户外场地将进行儿童友好的改造,他们仍然可以使用改造后的场地。宠物狗展览为场地的不同使用人群创造了交流机会,对促进社区公共空间的共享使用产生了积极促进作用。使公共空间的主要使用人群感受到重视和参与,并顺利开展了社区公共空间的儿童友好环境营造。

图4 研究人员在宠物狗展览现场The housing officer at the dog show

2.2.6 “运动日”活动

“运动日”活动是在位于两所小学之间的一个社区开展的。由于需要与2个小学同时进行沟通,该社区活动相比其他的社区活动花费了更多时间。“运动日”活动举办的最初目的是想要增进社区与当地小学的互动,将社区中的闲置空地加以改造,让其以崭新的面貌重新受到儿童的欢迎。谢菲尔德市市长出席了该社区举办的第一个“运动日”活动,并且在活动上颁发了复活节彩蛋搜寻活动的获胜奖品。自此以后,“运动日”已持续举办了8年。在第8年,共有来自两所学校的140多名小学儿童与15名学龄前儿童参加。在“运动日”举办的时候,学校的老师、活动组织人员、儿童的父母、爷爷奶奶、儿童的兄弟姐妹、邻居以及社区里其他围观者都会赶来为孩子们的比赛欢呼喝彩。在这8年中,孩子们见证了荒废的社区绿地焕发新的生机,成为深受儿童喜爱的地方,最初参与“活动日”的孩子现在已经长大了,他们的弟弟和妹妹在他们的带领下延续了对活动场地的使用,这些积极的使用方式甚至已经成为不同年龄孩子们之间传递的“游戏传统”。

2.2.7 “记忆中的街巷”活动

一些社区有较高比例的老年人口。老年人在一些情况下会认为吵闹的儿童户外游戏会影响到他们安静的生活。为消除这样的误解并促进老幼人群的交流,团队设计了一项名为“记忆中的街巷”的活动。这项活动通常在轻松愉快的下午茶氛围里进行。社区中居住的老年人会带来自己以前的照片一起回忆童年时社区的样子和童年经常做的游戏。“记忆中的街巷”一共在8个老龄化程度高的社区中开展,受到了老年人的普遍欢迎。在其中的一个社区,这项活动被保留下来并成为社区年度事件。谢菲尔德市市长也曾参与了“记忆中的街巷”活动,与老人共进下午茶,并带来了自己童年的照片;在活动中,一位八旬老人甚至带来了一些老唱片和周边地区的老照片和风景画。这些老唱片、老照片和风景画最后被拍卖,所得收益用于继续推进社区活动。现在,这些改造的儿童游戏场地,不仅是儿童喜爱的户外活动空间,同样也受到了老年人的欢迎。在老年人看来,这些场所不仅是带孙辈儿童进行游戏的地方,而且是老年人的户外社交场地,老人在这里可以结识邻居、认识新朋友。

2.3 社区儿童游戏场地设施更新

在“与自然共生”项目开展的社区儿童游戏场地通常设置在住宅间绿地中。这些儿童游戏场地质量普遍较差,仅由草地、灌木丛和穿过绿地的小径等简单的景观元素构成;并且儿童游戏设施大多已经损坏。在每个儿童游戏场地改造项目的最初阶段,研究团队都对用户对于场地的使用行为进行了细致的观察。结果发现不仅几乎没有居民会在这些游戏场地进行长时间停留,更没有儿童使用这些游戏场地,只偶尔有居民在这些场地散步或遛狗。

2.3.1 宅间儿童游戏场地

造成游戏场地因质量下降而闲置的主要原因是缺乏资金用于场地的持续管理和维护。改造前,秋千的座位已经损坏,只剩下框架;场地中央区域的交通岛也已不在,只在地面留下一个圆形的痕迹;也可以看到场地仍然保留着陈旧的攀爬架,然而攀爬架下面已经没有任何形式的安全铺装(图5)。在改造中,团队在场地中置入了一个用石笼围成的种植池。社区中的老年人参与了种植池的播种工作,他们多年来一直负责植物的修剪维护工作,直到因年老等不能再继续。由于该社区儿童游戏场地占地面积较大,设计师移除了大面积柏油碎石铺装的硬质区域,栽植树木,引入混植草坪,极大地提升了场地的生物多样性;同时也配置了新的游戏设备,采用灵活的布置形式为整个游戏场地提供了更加丰富的游戏机会,提高了整个场地的可游玩性(图6)。

图5 改造前的宅间儿童游戏场地Community playground before renewal

图6 改造后的宅间儿童游戏场地Community playground after renewal

2.3.2 通学路旁儿童游戏场地

第二个进行改造提升的场地在一条通往学校的小路旁(图7),许多学龄儿童在每天上下学途中会经过这个空间。在改造之前,这个场地只有一个没有了座位的秋千架,并且时常有社会不良青年在此聚集,这些情况导致了场地的失序感,让人感觉场地不安全,以至于不愿意在该场地停留。对该场地改造的第一步就是移除旧的秋千架,并将秋千架下的铺装场地改造成了草坪;在此期间,团队与当地的学校也进行了深入讨论,以便更有针对性地对游戏场地进行改造。实际上,与学校进行交流是一个比较漫长的过程,因为该学校坐落在城市较为贫困的地区,学校的主要目标在于提高教学质量,并没有太多精力与项目团队进行儿童通学路上游戏场地改造的探讨。当经历过较长一段时间的反复交流沟通以后,校方最终希望在上学的路上为儿童提供可进行短暂停留和安全游戏的小型游戏场地。于是,经过改造后的小型游戏场地配置有一个滑梯以及其他小型游戏设施(图8),以便为儿童提供他们喜爱的并且有趣的游戏机会。改造以后的游戏场有时也是儿童举办户外生日聚会的场地。

图7 改造前的通学路旁儿童游戏场地Routes to schools before renewal

图8 改造后的通学路旁儿童游戏场地Routes to schools after renewal

2.3.3 社区公共绿地儿童游戏场地

第三个改造的儿童游戏场地是一个位于社区公共绿地道路交叉口边的三角形场地,其两侧都有房屋,另一侧有林地。在设计团队眼中,这里是一个举办创意活动的绝佳场所。为充分发挥场所特质,整个场地在改造前后发生了很大的变化(图9、10)。在对该场地进行调研时,团队设计师发现冬天下雪的时候,孩子们经常在场地中的草坡滑雪橇。因此,为给孩子们提供宽敞的雪橇活动场地,场地中现存的游戏设施都被移除,只剩下草坪中可降解的地坪以及围合秋千区域的栅栏。完成了这一阶段的改造后,研究团队在该场地成功组织了多次社区参与型活动,这些活动吸引了居民的广泛参与;在观察了人们对于场地的使用行为以后,设计师决定在草坡上增设滑梯,与社区居民进行深入交流后最终确定了滑梯的具体位置。设计师认为还需要在场地中增设沙池,然而管理人员认为在该场地放置沙池会带来诸多管理问题,因此拒绝了该改造计划。在经过了与场地管理人员的漫长拉锯谈判后,最终增设了沙池。此外,在改造设计中秋千并没有采用呈直线布置的惯用形式,而是彼此成角度放置,这样可以为玩秋千的人提供更多交流的机会(图10)。场地原来的栅栏得以保留,重新粉刷以后在栏板上切出一个个圆形孔洞,让儿童可以透过孔洞张望,为儿童提供了更多玩耍的机会。

图9 改造前的社区公共绿地儿童游戏场地Public-spaces in communities before renewal

图10 改造后的社区公共绿地儿童游戏场地Public-spaces in communities after renewal

这3个设计改造项目是众多改造项目中比较有代表性的案例,也是团队在项目结题报告中着重展示的案例。这3个项目都阐释了如何用最少的经费支出,通过挖掘场地的特色为场地带来最大的改变,为儿童提供最丰富的游戏机会。在项目结题以后,这些游戏场地改造项目仍然在为社区持续带来深远影响,而这是研究团队没有预料到的。

3“与自然共生”项目反思与经验

3.1 可行性研究是确保项目顺利进行的关键前提

社区参与型活动是营造社区氛围、促进社区居民交流的最有效手段。社区活动成功的关键在于组织团队需要细致考虑活动全程所有步骤的可行性,以便能够对潜在安全隐患和风险进行预判并提出有效应对措施。以英格兰为例,所有在公共空间举办的参与型活动都需要进行严格的健康安全风险评估。风险评估需要考虑的事项包括:需要使用的工具和设备,活动过程潜在的安全风险,参与活动可能会带来的意外伤害(出行安全、滑倒等)以及食品卫生安全等。“与自然共生”项目中开展的所有社区参与项目也都严格遵守谢菲尔德和罗瑟汉姆野生动物基金会制定的儿童和弱势群体保护策略。此外,根据活动内容的不同,超过一定人数或者有现场表演的社区活动需要通过谢菲尔德市议会的特别许可才可以开展。由于有儿童和老人等社会弱势群体的参与,前期进行充分的可行性研究和风险管控预案是社区参与型活动得以成功开展的关键。

3.2 用开放的心态积极面对挑战

“与自然共生”项目开展期间,面对多元文化及不同社会经济背景的当地社区,研究团队遇到了诸多挑战,应对不同挑战的不同策略直接决定了社区活动的开展方式。例如,对于有不同宗教文化背景的居民居住的社区,充分了解社区的多元文化,记住不同文化的传统节日(如开斋节)和习俗对于在这些社区开展参与型社区活动至关重要。在为期3年的项目中,研究人员与多种文化背景的社区居民建立了深厚友好的合作关系,他们都对社区中公共空间所发生的积极改变感到高兴。因此,该项目的最终目的并非迅速提升社区公共空间质量,而是通过社区参与活动帮助社区居民展开对理想社区环境的想象,并且开放地讨论不同社区改造方案的可行性,在居民充分参与的情况下实现包容性社区的建设和社区友好和谐氛围的营造。

3.3 建立与社区的信任合作关系

“与自然共生”项目团队提供了一种成功在社区组织活动和对社区公共空间进行改造的模式,而这一切的基础是与社区建立互相信任的合作关系。虽然在项目最开始的阶段,研究团队并没有真正意识到与社区建立信任关系的重要性,但是随着项目的发展,研究团队越来越意识到社区的支持对于项目的成功至关重要。同时,团队也发现可以通过第三方团体,例如项目中提到的城市艺术团体和跑酷团体等,或者是在社区中具有一定威信力的人员来建立与社区居民之间的信任关系;或者与社区管理团队之间建立相互支持的友好关系,也有助于推进改造项目在社区中的顺利实施。

4“与自然共生”项目效益

“与自然共生”项目并未随结题而消逝,从项目开始执行至今,与自然共生的理念一直持续影响着社区的物质环境和社会环境。这个项目让居民重新审视并使用社区中的绿色场地,同时也提高了居民对社区环境和服务能力的满意程度。

4.1 游戏场地的游戏价值显著提升

在经过改造的社区中,游戏场地的游戏价值都得到了显著提高。关于游戏场地改造前后游戏价值的评估采用了Woolley & Lowe评价工具[5]。前后对比显示,所有改造后的社区游戏场地的游戏价值都有明显提升。以这些成功改造的案例为参考,2014年项目结束以后,又有另外3个游戏场地也自发进行了改造以提升场地的游戏价值。

4.2 游戏场地改造产生积极社会效益

项目产生的社会效益在于为社区中不同年龄、不同文化背景、不同生活方式的居民提供了友好交流的机会,让大家增进了解,促进社区形成友好包容的氛围。在项目结束以后,一些社区依然在定期举办深受居民欢迎的活动。这是研究团队在项目计划中未曾预料到的。在项目进行期间,研究团队在3个社区中尝试性地组建了以管理社区公共空间和提升社区的公共空间质量为工作内容的“友好小组”。这些“友好小组”让“人们聚在一起形成一个集体,可以共同影响社区发生积极变化”的信念和工作方式逐步深入人心。在“友好小组”的积极引导下社区居民学会建立共同目标工作团体,组织社区活动,以及与其他团体和组织合作完成工作。不仅如此,不同社区间也进行了合作与交流,通过一个社区帮助另一个社区开展活动,这些跨社区的交流实现了知识和经验的共享,让项目的社会效益实现了最大化。

如今,宠物狗展览、“运动日”“记忆中的街巷”等活动在一个示范社区中已连续举办了8年,社区的“友好小组”也依旧在努力工作,继续寻找方法让社区游戏场地的服务功能得到充分发挥,让社区居民可以更好地使用游戏场地。最初的发起团队很高兴看到社区活动现在仍然在延续,受到居民的支持和喜爱,尤其是受到儿童的热烈欢迎。现如今,这些活动甚至成为社区生活的一件盛事,让改造后的场地保持长久的活力,形成了社区的特色,甚至为社区场地的持续维护争取到更多赞助资金。社区中四季变化的绿色空间、具有创意的游戏干预、丰富的社区活动、持续的资金投入以及其他基础社区的改善提升是“与自然共生”项目的延续。项目为社区带来的多元效益远超当初的设想,并将可持续发展下去。

5“与自然共生”项目经验

英国《儿童发展计划》政策背景下实施的“与自然共生”项目对于中国“十四五”规划背景下儿童友好城市建设的借鉴意义,主要可以归纳总结为:1)在社会政策方面,该项目发动全社会力量共同致力儿童发展,并且积极推动儿童参与并融入城市社会生活;2)在城市空间品质提升方面,该项目推进了社区空间的儿童友好改造,为儿童提供了更加丰富的游戏机会。该项目以社区儿童游戏场地的自然化改造为切入方式,成功实现了社区的儿童友好环境创建。

5.1 多元参与共同推进儿童友好环境建设

笔者详细介绍了在英国体制背景下政府总体规划政策在地方层面实施的全过程。在此过程中,以科研团队为核心的项目团队,通过整合政府部门、当地社区、高等院校、社会组织、基金会等多个组织机构,运用专业特长,通过开展前期策划、项目设计以及项目后期评估,实现了儿童游戏场地的全流程设计实践,充分发挥了科研理论对于设计实践的指导作用,推动实践项目在社区层面的顺利开展、运作甚至取得超出项目预期的成果。该项目对于我国儿童友好型城市建设中提出的“多元参与,凝聚合力”基本原则的实践具有借鉴意义,在一定程度上可以帮助中国的儿童友好城市工作人员开阔视野,积极思考多领域、多部门协同工作,发动全社会力量共同为儿童创造适宜其成长的城市环境。

5.2 鼓励儿童全方位参与社区社会生活

此外,研究通过对社区活动组织方式和儿童游戏场地改造方案的介绍,丰富了社区参与型活动的组织方式,为组织有趣多样的社区活动提供参考;通过8年的持续观察,诠释了儿童参与社区活动的意义在于营造充分满足儿童需求的儿童游戏场地,并在游戏场地形成可以传承的独特游戏方式,创造真正属于儿童的社区空间;同时,该项目也充分展现了非政府机构或组织在营造儿童友好型社区时发挥的积极作用,为自下而上型的儿童友好型社区创建提供了借鉴经验。

5.3 社区公共空间的儿童友好型改造方式

社区作为儿童日常生活圈中最主要组成部分,其儿童友好程度对儿童的成长体验有重要的影响作用。提升社区空间品质和社区服务效能是推进儿童成长空间友好程度的有效手段。“与自然共生”项目通过将传统“KFC”游戏场地进行自然化改造,充分开发了游戏场地的游戏价值,实现了社区公共空间对于不同年龄段儿童游戏需求的服务效能提升。因此,自然化的儿童游戏场地设计方式可为中国城市社区儿童游戏场地空间品质提升方案提供思路。

综上,英国英格兰地区实施的“与自然共生”项目,其成功经验在多元协同工作机制、儿童参与方式以及社区空间改造等方面为我国儿童友好城市的建设提供了参考。综合考虑我国的城市经济社会发展情况,该项目为因地制宜地创建中国儿童友好城市面临的机遇与挑战,提供了国际前沿的实践策略和经验。

图片来源(Sources of Figures):

文中图片均由作者拍摄。

(编辑/王亚莺)

“Living with Nature”: Improving Urban Green Spaces for Children’s Play

(GBR) Woolley Helen, (GBR) Somerset-Ward Alison, (GBR) Bradshaw Kate, TANG Pai

1 Background

1.1 Changing Policy on Children’s Outdoor Environments in England

The child’s right to play is enshrined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child[1]and expressed in differing ways in the countries which are signatories to the convention.In England the best expression of this was possibly the period of three years from 2008 to 2010 when the Labour government of the time introduced a Children’s Plan[2]and Play Strategy[3]. The latter set out a direction for the country for the refurbishment of existing and provision of new outdoor play spaces within local authority areas across the country. A total of 3,500 playgrounds would be improved or built and the policy was supported by £235 million to be spent by the local authorities in this programme. For the previous 50 or so years playground in England, and many other parts of the world, had become increasingly similar in what they provided for children and how they looked. This Kit, Fence, Carpet approach[4]did not take into account the breadth of play opportunities such spaces could support if they were well designed nor did they use specific landscape elements, such as landform, vegetation, sand, water and loose parts. One aim of the government’s programme was to move the provision of outdoor playgrounds away from this approach to be more natural in style providing increased contact with nature and improved play value[5].

To help local authorities with this programme of playground improvement two documents were commissioned and published by the government for England. Design for Play[6]suggested 10 principles for designing successful play spaces and provided many inspiring illustrations and case studies. Accompanying this was Managing Risk in Play Provision[7]which explained the concepts and understandings of safety, risk, hazard and harm, together with the legal and policy context with respect to outdoor play. This document went on to introduce the concept and practice of a Risk Benefit Analysis[7]in order to support the introduction of more challenge in outdoor playgrounds than a traditional Risk Analysis might allow for. This document was a great achievement,partly because of the different partners who were involved in its development and who signed up agreeing to it. These two documents provided a policy and practice framework for local authorities to work for the funding programme.

In 2010 the UK General Election returned a Conservative-Liberal Democrat government and the former party, wanting to save money,immediately cancelled the remainder of the funding programme for the outdoor playgrounds.Most of the playgrounds had been built or were in a contract that could not easily be cancelled, and so were saved. All of the previously mentioned policy,practice and guidance documents were no longer considered appropriate and were placed in the government archive.

Once these documents were no longer deemed relevant by the government and the funding programme for outdoor playgrounds was not extended the only way forward to continue to improve outdoor playgrounds was by the enthusiasm and commitment of others who understood the importance of good quality outdoor play spaces for children. If this were to happen there was also a need for smaller amounts of funding from non-governmental bodies.

1.2 Working with Communities

Working with communities has been a requirement for some planning and practice projects in England since the 1970s. The Town and Country Planning Act (1970) required planners to engage with communities but did not define who the community was or how they should be engaged. Over the years a series of funding programmes by the government and the National Lottery (introduced in 1995) required applicants to engage with communities and this was shown by the applicant ticking a box. The lack of explanation as to how communities should or could be involved in projects resulted in methods such as public meetings or exhibitions being frequently used.Such methods are considered to be “tokenistic”nonparticipation on Arnstein’s[8]Ladder of Citizen participation.

At the beginning of the 21st century this began to change with projects funded by the Big Lottery who wanted to know that the projects their money was funding were not only benefitting communities but involving them during the project. The Playbuilder funding associated with the Children’s Plan was another programme expecting communities to be involved in how money was spent but some criticised the fact that the timescale did not allow enough time for meaningful working with the communities. Once the funding programme finished the only way to continue any improvement in urban play areas was through individual projects. Allowing children to be involved in decisions affecting their lives —children’s participation — is also an article of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. Much has been written about children’s participation, but less has been explained about what changes such participation has resulted in.

This paper goes on to explain some aspects of one project beyond the national programme of funding for outdoor playgrounds. Living with Nature, took place in the northern city of Sheffield with funding between 2011 and 2014. The paper will discuss the background to the project, some of the process of working with the communities,examples of the product or outcome of the project, specifically improved play areas, and aspects of the legacy of the project.

2 “Living with Nature”: Project Content

2.1 Introducing Living with Nature

Living with Nature was a three year programme(2011–2014) funding by the Big Lottery Reaching Communities programme. It developed from the enthusiasm of a housing officer in the City of Sheffield who wanted to improve the outdoor play spaces in the green spaces associated with the social housing managed by Sheffield City Council.These provide homes for about 20% of the city’s population for people who are usually on lower incomes. The budget for the maintenance of the outdoor play spaces had reduced over a period of years and in this resulted in many playgrounds having pieces of equipment removed and the spaces falling into disuse and deteriorating in quality.

In 2006 the housing officer heard the author speak about how playgrounds could be better than the Kit, Fence, Carpet approach by being designed to include natural elements. She immediately contacted the author to ask for help but at that time there were no resources with which to help.The author never forgot that phone call and 18 months later I was able to invite the housing office to a discussion about play and housing. Following this two things happened. First of all for several years they worked on some of the housing sites as second year undergraduate projects. These gave students opportunities to spend time with some of the residents in the housing areas and resulted in the students producing plans for the playground which provided some inspirations for the communities. Second, two of us who were CABE Space Enablers worked with the housing officer to develop a play strategy for the playground across the city for which the City Council Housing Services was responsible.

In 2010 the first author obtained a small amount of funding from their university for a“Knowledge Exchange” project which enabled one of our graduates (second author) to work with the housing officer (third author) to start to work one of the priority sites identified in the play strategy which later became known as the “pilot site”. As time went on the Sheffield and Rotherham Wildlife Trust became involved and led the writing of the funding proposal to the big Lottery Reaching Communities Fund. This was successful and the project started in July 2011. Most of the money was for staff and for the process of working with 24 communities associated with the green spaces that had playgrounds and had been identified as the priority spaces for improvement in the Play Strategy.

The funding paid for a Landscape Architect and a community engagement officer specifically for this project, some additional time for the housing officer and time for the project manager and for the first author speak as the advisor and chair of the steering group. The steering group included all these partners: Sheffield Housing Services, Sheffield and Rotherham Wildlife Trust and The University of Sheffield. Additional staff from other parts of Sheffield City Council, two from housing and one from parks and countryside,also attended some of the steering group meetings.A part of the funding was for the product of changing the physical state of 8 sites identified as priority in the Play Strategy, and to this was added contributions from one project the wildlife trust was involved in and a wide range of smaller amounts of money which communities applied for,with the support of the project team.

As is often the case the funding body for the project required targets as part of the evidence that the money had been spent on the project. All of the numerical targets for numbers of events and organisations to be involved were exceeded.Organisations involved in the project included Tenants and Residents Associations (TARAs),Friends Groups (of a specific green space),Community Centres, sheltered housing and old people’s residential homes, residential homes for disabled people, a hostel for homeless people, a local community wildlife trust, the local police,churches, libraries, another social housing provider,local urban artists and the Sheffield Royal Society for the Protection of Animals (RSPCA). The organisations specifically involving children include nurseries (children aged 0-5), primary schools(children aged 6-10), and secondary schools(children aged 11-18), after school and holiday clubs, youth groups, the Sheffield Parkour Group,a mobile children’s library and a local children’s hospice.

2.2 “Living with Nature”: The Process

Twenty four sites were identified from the Play Strategy as being the priority for improving the playgrounds and therefore for working with the associated communities. One aim of working with the 24 communities was to understand how they might want to use the spaces when they were redesigned. Understanding how a space might be used by children and other members of the community was one way of informing the re-design of the play spaces and was particularly important for details such as where pieces of fixed play equipment, such as slides, might be placed on a site.This was done by informally observing children’s and adult’s activities on the sites during a range of activities facilitated by the project team. In addition these events were used as mechanisms for talking with members of the community about the green and play spaces. This dialogue was made possible because of the presence of the housing officer who was known by many of the residents in the different areas. Informal observation of children and adult behaviour together with discussions at the onsite events satisfied the project team’s desire to work in the middle to upper range of Arnstein’s ladder of participation.

The project team developed a palette of activities, from which they drew on for each of the sites, to work with the communities. Additional or different activities were introduced if these were more appropriate to an individual community. The housing officer and community engagement officer worked with the communities, building on the relationship the housing officer already had with people, to initiate and organise the events. Other partners joined the project, often relating to one specific site, and taking on a range of activities.Some of the activities undertaken will be explained:the introductory Fun Day, planting activities,creative and art activities, physically creative activities, a dog show, sports day and Play Down Memory Lane.

2.2.1 Fun Day

On each site the first event would be a“Fun Day” which would allow the children and community to start using the green spaces in the context of feeling safe, because of the organised nature of the event. In addition the project team began to make themselves known to the local children and community and start conversations about the potential future use of the space (Fig. 1).The Fun Day would include specific activities such as den building, martial arts, art and craft, a bouncy castle, a temporary sand-play area, team games and face-painting for the children.

There was always a tent where refreshments were served including hot and cold drinks,homemade cakes and ice-cream (with a free voucher). As the project went on it became clear that the refreshments were a really important aspect of these events for the members of the community.

2.2.2 Planting Activities

A wide range of planting activities were used across the different sites. Children were involved in planting bulbs, bluebells, perennials, herbs,wildflower meadows, hanging baskets and fruit trees. Small plants or seeds in containers decorated by children allowed the project’s aims to escape the boundary of the project site taking new planting out into the community. The children enjoyed taking a small part of the project home with them and taking care of it themselves (Fig. 2). Planting was a very popular activity with almost everyone at all the 24 sites. It was an activity that people of all ages participated in from early years groups to older adults and those with a range of abilities. Plants connected people to places in a way that nothing else did. The team worked with lots of schools to undertake planting at their local site and at some sites raised planters were built for the school to take over and maintain in the longer term.

2.2.3 Creative and Art Activities

Different creative activities were focussed on the character of the local community. Urban art,environmental installations, murals, sign design and decorations to temporarily or permanently transform sites, lantern making followed by a Christmas parade through the outdoor environment,painting bricks, nature mobiles, bird boxes, living letters and autumn crown making were all used(Fig. 3). Many of these activities used natural materials that were either found on site or brought by the children and the team. Art and craft activities were very popular and inclusive for all ages and abilities. The project team worked with a variety of other organisations in developing some of these activities in particular with primary schools and early years settings. The project also drew on local art practitioners such as the Urban Art group“My Life Project” a social enterprise working with children and young people across the city to develop a range of skills including spray art, t shirt printing and mural design. This group worked at a number of sites very successfully and this was something that older children and young people were keen to engage with. This allowed the team to talk with the young people about the needs and issues of their local green spaces in an informal way.

Young people from one secondary school were asked to think about ways of looking at outdoor places and to explore the concept of views both internal and external at one of the sites. A series of images and ‘frames’ were made to capture a range of both macro and micro views within the site, which were photographed by the young people. The young people were asked questions such as: Where did they find interesting at the site? Why? What type of use could they make of the site and where might this happen? These were discussed through their art work and exploration of views.

Working outdoors for the most part and with a mix of natural and non-natural materials the project offered the chance to transform familiar spaces through temporary changes or artistic interventions or even transform themselves into works of art. At one site local children were asked to become “Living Sculptures” and create a living sculpture trail. They designed costumes and art work to wear and gave a show at the site,the space was changed for a few hours and only the photographs and memories remain. However,the children realised they could transform the site themselves and have an impact on their own environment.

2.2.4 Physically Creative Activities

These included den building, orienteering,sculpture trail, Easter egg hunt, map making and trail setting. One child created a game called “Here to There” which was a building game using “junk”materials to get from one piece of play equipment to another without touching the ground. The team used this new game at many other sites because it was very successful and thoroughly enjoyed by all the children who engaged with it, not just the originator of the game. Because this active approach was welcomed by the children the team decided to invite a local parkour group to work with children at one of the sites. This helped the children find new ways of using the site including the existing fixed equipment, the landform and other natural features in more exciting ways than they would otherwise have done. Over time the team observed how and in what ways the children were using the space and eventually the landscape architect designed some basic interventions which would extend and enhance these uses making the space physically more challenging and engaging.

2.2.5 Dog Show

Because the pilot site was used by dog walkers the team initiated a dog show, something which we believe to be a unique and innovative community activity (Fig. 4). The dog show was intended to ensure that dog walkers, who were often the people who used a site most regularly and in many instances, were aware of what happens there, did not feel they would no longer be welcome on the site if changes were planned. Having the dog show highlighted their presence and made sure they felt welcome and included.

2.2.6 Sports Day

The introduction of a sports day between two local primary schools took some time to establish. In time this activity brought together two schools local to the pilot site who previously did not relate to each other, indeed hardly knew of each other. The first sports day was attended by the Lord Mayor who gave out the winning prizes of Easter eggs. The initial concept for the sports day was to engage with local school children and re-introduce them to the play space which was unused and mostly ignored as being “boring” and “just for dogs and alcies” (alcoholics). The sports day started with one class of children from one school and in its’ eighth year saw over 140 primary school children from two schools take part together with 15 children from a nearby early years setting who have their own races organised by the older children. Children are accompanied and cheered on by teachers, support staff, parents, grandparents,siblings, neighbours, dog walkers, alcoholics and anyone else attracted by the noise and fun in the park. Over the eight years the children have seen the gradual changes and improvements at their local green space and it has become a very popular and much valued place on their neighbourhood play map. The original children are now teenagers and younger brothers and sisters have followed in their footsteps, “it’s a tradition now”.

2.2.7 Play Down Memory Lane

Some sites still had a high percentage of older residents and this, together with the fact that sometimes there are misunderstandings about children’s play by older people, resulted in an activity called ‘Play Down Memory Lane’. These afternoon events included tea and cake and gave the older people the opportunity to bring photos of their memories to discuss their childhood play experiences with each other. This event was held at each of the eight priority sites and was very popular with older adults living close by. At one site the event has become an annual event. One year the Lord Mayor of Sheffield joined regulars for tea and cakes and brought some play memories of her own along to share, a local octogenarian provided some songs and there were vintage photos and paintings of the surrounding area on show and for sale with all proceeds going towards continuing the work at the local play space started during Living with Nature. The Play space is now popular with many older adults not only as a place to take their grandchildren but also as somewhere they can enjoy themselves, an outdoor social space to meet neighbours and friends.

2.3 “Living with Nature”: The Product

The playgrounds were set within a green area associated with each specific housing area yet the quality of the green area was poor usually existing of only grass, sometimes old shrubs and with paths through the area. On most sites the fixed play equipment had become damaged or broken and needed to be removed. One of the first things the project team did was to undertake observations of site users in the first months of the project which revealed very few users, only people walking through or walking their dogs. No-one was remaining in the spaces and no children were using the playgrounds.

Three examples of the 8 priority sites are shown below. Photographs are a valid form of data and sometimes pictures can speak louder than words, so for these three sites before and after photographs will be supported with limited text.

2.3.1 Community Playground

The lack of funding for maintenance at the ‘pilot site’ had resulted in swing seats being taken out leaving only the frames. In addition the circle that can be seen in the tarmac is where a roundabout was placed. An old climbing frame remained but without any form of safer surfacing beneath it (Fig. 5). During the initial pilot project a planter was made of gabions and planted up.Some of the older people in this community looked after the planting and have remained involved over a long number of years, until they were no longer able because of their health. The space associated with this housing area was quite large and the biodiversity was improved with the removal of tarmac areas, new tree planting and the introduction of differential mowing of the grass.New fixed play equipment was introduced in a less formulaic way than previously making the whole of the green space playable (Fig. 6).

2.3.2 Routes to Schools

The second site was on a route to a school that is used by many children everyday on their journey both to and from school (Fig. 7). The small playground had swing frames with no swings and there was evidence of anti-social behaviour such as drinking, and even drug taking. This added to a sense of dereliction and of the space not being safe to use.

The first physical change made to this small site was to remove the old swing frames and take up the tarmac. This was seeded with grass as an interim improvement because it was important to start the process of regeneration the space while the team worked with the local schools. Working with the community was a long process because the school had poor educational performance,partly because it is set in an economically and socially poor part of the city, and was focussed on educational improvement and thus did not have time to work with the project team. In time the team was able to work with the school and the desire was to have a play trail on the way to school.This small space now includes a short slide and other interesting and popular play opportunities clearly evidenced when some of the team were walking past and found a children’s birthday party using the new space. An alternative route to school,down some steps and a sloping path were enhanced for play by introducing a slide on the embankment and some informal elements for play to the side of the path (Fig. 8).

2.3.3 Public-Spaces in Communities

The third site was set back from a road junction, triangular in shape, with housing on two sides and woodland, which was used for many of the creative activities, on the third side. There is a large change in level across the site and while working with the community the project team discovered the slope is used for sledging when there is snow (Fig. 9, 10). All the play equipment had been removed leaving only the degrading tarmac in the midst of the grass and some of the fencing that used to surround the swings. The many vibrant activities that took place here in time attracted many people including residents from other parts of the city. The slope was immediately identified by the landscape architect as being in need of slides and working with the community revealed which part of the slope was used for sledging and therefore which part of the slope was suitable for the slides.

The introduction of sand in the play area took a lot of hard negotiation with the managers of the space because of their perceived issues with sand. Swings were not placed in a straight line, as usually happens, but were positioned at an angle to each other to make the experience more sociable.The original left over fencing was retained, repainted and had a circular hole cut in it, providing an additional opportunity for children’s play.

These three sites provide examples of the end product of the funded project and show the physical changes which could take place with relatively small amounts of money. However beyond the end of the funding some of the sites have a legacy which the project team did not anticipate.

3 “Living with Nature”: The Reflections

3.1 Practical Issues

As with any community activities the project team had responsibilities for a range of practical issues when planning, preparing and undertaking the events with and for the communities. Health and safety risk assessments were required for every activity because they all took place on council owned land. These risk assessments considered issues such as using tools and equipment, taking part in activities on site which may carry a risk to the participant, physical hazards on site such(trips, slips falls etc.), food standards and hygiene.There was also the important consideration of child and vulnerable adults protection policies and procedures set by the Sheffield and Rotherham Wildlife Trust. These were adhered to at all times along with a policy about gaining permission to use photographs. Public Liability insurance was needed at every site. Some events, depending on their nature, required a special licence from Sheffield City Council which covered activities where more than a certain number of people might attend and where live music or any sort of live performance was going to be part of the event.

Other practical issues related to setting appropriate dates and locations for activities. This meant that activities targeted at children might take place in school holidays on the site, the sports day date was negotiated with both schools and took place on site. Many art, urban art and creative nature activities took place on the relevant community’s green space.

3.2 Limitations and Challenges

There were of course limitations and issues that influenced the planning, preparation and undertaking of events. Some communities included people of Pakistani heritage, the major ethnic minority group in the city, and remembering different cultural festivals such as Eid was very important. The project team worked with a diversity of cultures over the 3 year project and found unsurprisingly that Christmas was universally popular but particularly popular with Muslim children. Most people taking part in the project and living locally to the sites were just happy that there were positive things happening at the neglected and un-used play and green spaces close to their homes.The challenge was not to raise expectations too high as to what could be achieved in the short term but to raise aspirations as to what was possible and to help them re imagine how these places could be used then and there and in the future.

3.3 Some considerations

Many of the activities were conceived of,initiated and organised by the Living with Nature project team who provided a mechanism to organise the activities with the communities, which would not otherwise have happened. In reality the project and the team were the stimulus for a wide range of community events and activities.

On reflection some specific issues were deemed important to enhance the events and activities. One of these was the provision of food and the form of this varied from event to event.The type of food reflected the event or the season or was just what people asked for. Often the team invited local caterers, supermarkets or cafes to contribute food and drink or to cook or make something they thought would be appropriate.Sometimes people brought their own food for an event called “bring your own blanket” which was a community picnic with entertainment, games and music. Even if it was just tea and biscuits providing food was always a way to create a social atmosphere and a way to open a conversation whatever the language.

The importance of developing relationships with and the trust of individuals, groups and communities had not been anticipated but as the project developed it became clear that this was an essential approach to the success of the project.

4 “Living with Nature”: Legacy

Often projects end when the funding ends but the team are delighted that seven years on from the end of the funding Living with Nature has a legacy. This legacy is both physical and social and is evidence of the need and desire that there was to re-engage with the community’s green spaces, and for an increased level of socialisation within some of the communities.

4.1 Physical Legacy

Physically all of the eight priority sites have changes that have improved the play value from what it was before the project. Although not published this was evidenced by a Masters student dissertation undertaken in summer 2016 which assessed the play value of the spaces as they were,from photograph’s, and as they are now, from site visits, using the Woolley Lowe tool[5]. This assessment of the difference in the play value before and after the project showed an increase on all the sites. In addition to the eight priority sites, three of the other sites have also had physical improvements to their play space or community green space since the end of the project in 2014.

4.2 Social Legacy

Underpinning these physical activities has been an ongoing, and unanticipated, social legacy which takes several forms. First, three Friends groups began during the project. The first of these was on the pilot site and facilitated by the housing officer because of her concerns that the Tenants and Residents Association (TARA) was not expressing much interest in the green space.TARAs exist to represent tenants’ views to their landlord in a corporate way and have a focus on housing and the built fabric not on green spaces.In order to raise the profile of the green spaces the housing officer decided that a different mechanism was needed and so supported the establishment of a Friends group on the pilot site. This was successful and as time went on opportunities for Friends groups to be developed associated with two other sites were taken and became part of the ongoing legacy of Living with Nature. Part of the social legacy at some of the sites where a Friends group was formed was more around building confidence and an understanding that as a group people could come together and influence change in their community, building skills and learning how to organise and work as a team but also how to work in partnership with other groups and organisations to get things done. Cross community partnerships was not something we envisaged but which happened at a number of sites during the project and beyond with one community helping another to deliver an event or activity becoming quite a regular occurrence along with sharing knowledge and experiences.

Activities such as the dog show, sports day,Play Down Memory Lane have now taken place for eight consecutive years on one particular site. The Friends group there have worked hard and continue to work to find ways to make their neighbourhood play space a valued and well used place for the surrounding community. The events started during the Living with Nature project at one site are now seen as important as part of the local“calendar” and are well supported and enjoyed by all age groups but especially by local children who have seen their play space transformed over the last eight years. At other sites where “Friends” groups have been formed there is also a continuation of activities and events to a lesser degree: regular litter picks, planting and gathering fruit are all part of a cycle of activities which keep the sites active and used, whilst play days and other activities during school holidays are a feature at some sites. There has also been a continued drive to access additional funding by some Friends groups and community groups at some of the sites and this has had some success. New planting, play interventions, funding for events and activities, additional seating and other further improvements have meant that Living with Nature has had a level of sustainability into the future which was not initially envisaged.

5 “Living with Nature”: Lessons

The “Living with Nature” project implemented under the policy of the “Children’s Plan” in the United Kingdom has a reference to the construction of child-friendly cities under the background of China’s “14thFive-Year Plan”.Learned from the ‘living with nature’ project, this project mobilizes the whole society to participate in the construction of child-friendly environments in communities, and actively promotes children’s participation and integration into urban social life.At the same time, this project also improves play value of playgrounds in communities by designing playgrounds with more natural elements.

5.1 Joint-Participation in Generation of Child-Friendly Environments

This article introduces in detail the whole process of the implementation of the government's overall planning policy at the local level under the background of the British society. In this process,the project team with the academic research team played the key role to integrate the government departments, local communities, colleges and universities, social organizations, foundations and other organizations. By working together, there were significant improvements in the communities.This experience might help to provide the general idea about working together to mobilize the forces of the whole society to create child-friendly city in an effective way. To a certain extent, it can help the Chinese landscape architects and urban planners to broaden their horizons and actively think about multiple fields and multiple departments.

5.2 Ways to Encourage Children to Participate in Community Social Lives

In addition, this article provides a detailed introduction to the organization of community activities and the renovation of children’s recreational venues during the project, which greatly enriches the effective organization methods of community participation activities. At the same time, the project also fully demonstrated the power of non-governmental organizations in creating a child-friendly community, which helps providing a reference for the creation of child-friendly community in Chinese cities.

5.3 Methods to Create Child-Friendly Public Spaces in the Community

As the most important part in the daily life cycle of children, the community environment has an important influence on children’s experiences of growing-up. Improving the quality of outdoor environment in communities can be an effective means to promote the friendliness of children’s growth space. The “Living with Nature” project promotes the naturalization of children’s playgrounds by changing the traditional Kit, Fence,Carpet playgrounds into playgrounds with more natural elements, which largely increases their play value for children in different ages. Therefore, the natural design of children’s recreational venues can provide solutions for the improvement of the spatial quality of children’s playgrounds in urban communities in Chinese cities.

In summary, the development process and successful experience of the “Living with Nature” project help to provide suggestions for the construction of child-friendly cities in China in terms of building joint working groups, child participation methods, and methods of design playground with better play value. Taking the economic and social background of Chinese cities into consideration, the project provides practical strategies and experience to create child-friendly cities from an international perspective.

Sources of Figures:

Photo credits to authors.

(Editor / WANG Yaying)