Removal of laparoscopic cerclage stitches via laparotomy and rivanol-induced labour: A case report and literature review

INTRODUCTION

Cervical incompetence is the main cause of late-term abortion and premature delivery, for which cervical cerclage is the primary treatment[1,2]. Cervical cerclage is a surgical intervention involving the placement of stitches around the uterine cervix to prevent the shortening and opening of the cervix. Transvaginal and laparoscopic cerclage are the main methods. Transvaginal cerclage is the most widely used[3], while laparoscopic cerclage is used for patients with abnormal cervical anatomy and/or transvaginal cerclage failure. Laparoscopic cerclage is primarily used before or during the early stages of pregnancy, and the stitches are usually removed during caesarean section[4]. However, for patients with foetal abnormalities or second- or thirdtrimester foetal death, the method of removing the stitches to allow for labour induction remains controversial. In all previous cases of laparoscopic cerclage, labour induction was implemented in the second trimester, and cerclage stitches were removed either laparoscopically or transvaginally[5-10].

Herein, we report, for the first time, a case in which the patient, who had undergone laparoscopic cerclage, underwent removal of stitches by laparotomy and labour induction in the third trimester of pregnancy.

CASE PRESENTATION

Imaging examinations

Foetal three-dimensional ultrasonography showed ‘tulip’-like external genitalia, external penis and scrotum transposition, single umbilical artery, disappearance of umbilical blood flow in the diastolic period, and foetal intrauterine growth restriction.

I felt helpless, unable to take the pain away from my little friend. Then suddenly, an idea came to me. Bending over, I whispered in his ear, Timmy, did you know that geckos [our Hawaiian lizards] grow their tails back and little boys can grow their fingers back too?

Laboratory examinations

No abnormal laboratory examinations.

Physical examination

On the ship, in which she had left the prince, there were life and noise; she saw him and his beautiful bride searching for her; sorrowfully they gazed at the pearly foam, as if they knew she had thrown herself into the waves

Personal and family history

The final diagnosis was foetal malformations.

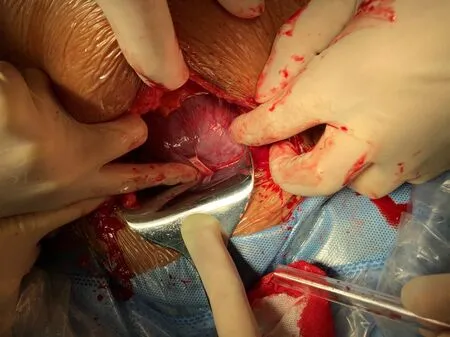

After relevant examinations, cerclage stitches were removed, and rivanol amniocentesis was performed for labour inductionlaparotomy under combined spinal-epidural anaesthesia. A mini horizontal incision was made in the middle of the abdomen, and the cerclage stitches were separated carefully from the cervix and surrounding tissue to which they were closely adhered (Figure 1). The stitches were clipped and removed. Amniocentesis was then performed, and 0.2 g rivanol was injected into the uterine cavity. Finally, the abdominal incision was sutured routinely.

History of past illness

A 31-year-old woman (gravida 4, abortus 3) was admitted for labour induction at 31 wk of gestation because of severe foetal malformations.

During the routine obstetric examination, severe foetal malformations were identified through three-dimensional ultrasonography; thus, the patient requested for induced labour.

History of present illness

Then she was sent into the kitchen, where she carried wood and water, poked7 the fire, washed vegetables, plucked fowls8, swept up the ashes, and did all the dirty work

Chief complaints

The patient experienced two miscarriages in the second trimester of pregnancy, one of which was caused by transvaginal cervical cerclage failure. Before the present pregnancy, laparoscopic cervical cerclage was performed under general anaesthesia, and the isthmus of the cervix was ligated with Mersilene tapes (RS22, Ethicon, NJ, United States).

No abnormal physical examination.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

No special personal and family history.

TREATMENT

Beware of it! The prince read and bared his head and lifted his hands in supplication to Him who has no needs, and prayed, O Friend of the traveller! I, Thy servant, come to Thee for succour

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Two days following labour induction, the patient delivered a dead foetus and was discharged 2 days later.

On the sand reef lay the wreck of a ship, which was covered withwater at high tide; the white figure head rested against the anchor,the sharp iron edge of which rose just above the surface. Jurgen hadcome in contact with this; the tide had driven him against it withgreat force. He sank down stunned with the blow, but the next wavelifted him and the young girl up again. Some fishermen, coming witha boat, seized them and dragged them into it. The blood streameddown over Jurgen s face; he seemed dead, but still held the young girlso tightly that they were obliged to take her from him by force. Shewas pale and lifeless; they laid her in the boat, and rowed as quicklyas possible to the shore. They tried every means to restore Clara tolife, but it was all of no avail. Jurgen had been swimming for somedistance with a corpse in his arms, and had exhausted his strength forone who was dead.

DISCUSSION

Laparoscopic cerclage is a type of trans-abdominal cervical cerclage. The isthmus of the cervix is sutured under laparoscopic guidance before or during early pregnancy. Compared with transvaginal cerclage, laparoscopic cerclage causes less trauma and has a lower risk of infection[11]. In addition, laparoscopic cerclage stitches are placed closer to the internal cervix, which more closely conforms to the normal physiological anatomy. Laparoscopic cerclage is effective not only in reducing the risk of cervical tear and infection but also in maintaining the expansion of the amniotic cavity[12,13]. In clinical practice, several obstetricians have performed this technique in women with cervical defects to extend the gestational age of the foetus, as well as in cases where transvaginal cerclage was not possible and in cases with repeated transvaginal cerclage failure.

Laparoscopic cerclage stitches can be removed by laparotomic, laparoscopic, and transvaginal approaches. For pregnant women with normal foetuses at full term or near term, caesarean section is commonly performed for delivery, and cerclage stitches were removed during the procedure[14]. For pregnancies that should be terminated because of foetal abnormalities or third-trimester foetal death, the methods of removing cerclage stitches and inducing labour remain controversial. Burger[6] reported three cases of removing transvaginal cerclage stitches in the second trimester. Carter[7-10] and other authors have reported laparoscopic removal of cerclage stitches in pregnancies terminated due to premature rupture of membranes or foetal abnormalities in the second trimester (Table 1). However, in the present study, the patient was already at 31 wk of pregnancy. She was informed of the risks of labour induction and caesarean delivery. Subsequently, she requested for induction of labour, but not caesarean section, to maintain the integrity of the uterus for future pregnancy. Therefore, we considered removing the stitches for a vaginal delivery. The enlarged uterus limited the surgical space in the abdominal cavity; therefore, laparoscopic removal of the stitches was not feasible. In addition, given the abundant pelvic blood supply during pregnancy, the stitches may be adhered to the surrounding tissue, and transvaginal stitch removal may cause injury to the surrounding tissue or intraabdominal bleeding. Therefore, stitches were removed by laparotomy and rivanol was injected directly into the uterus to induce labour.

To the best of our knowledge, no study has reported the removal of laparoscopic cerclage stitcheslaparotomy simultaneously with labour induction in the third trimester. The method of terminating a pregnancy is usually restricted by transabdominal stitches, especially in cases with premature rupture of the membrane or foetal abnormality in the second or third trimester. Obstetricians should comprehensively assess the methods of removing cerclage stitches to reduce the risk of injury to the patients; this indicates the need to develop new laparoscopic cerclage techniques. Sukur and Saridogan[15] sutured cerclage stitches behind the cervical isthmus, allowing the removal of these stitches through the vagina. Shaltout[16] designed an improved laparoscopic cerclage, which involved opening the peritoneum folding between the uterus and the bladder, puncturing the needle through the posterior fornix of the vagina, and placing the suture knot in the posterior fornix. Among the 15 patients who underwent this new surgical method, 12 underwent induced vaginal delivery after the stitches were removed through the vagina. Wang[17] performed ‘vaginal removal’ of laparoscopic cervical cerclage without opening the peritoneum folding, through which the cerclage stitches can be sutured to the posterior fornix of the vagina. Procedures were performed on 13 patients, of which four underwent vaginal delivery after 36 wk of pregnancy. The improved laparoscopic cerclage enabled the removal of the stitches through the vagina and avoided potential traumas caused by transabdominal surgery.

CONCLUSION

Foetal abnormality or death in the third trimester of pregnancy in patients who have undergone laparoscopic cerclage is extremely rare. In the present case, cerclage stitches were removed by laparotomy and vaginal delivery was possible following successful induction of labour, which maintained the integrity of the patient’s uterus. This is an alternative method for patients undergoing induced labour in the third trimester. In addition, obstetricians should improve prenatal examinations of patients who have undergone laparoscopic cervical cerclage during pregnancy to detect pregnancyrelated complications as early as possible and thereby avoid adverse events. More laparoscopic cerclage techniques should be developed, and existing techniques should be improved to increase the number of options available for removal of stitches.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2022年1期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2022年1期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Omicron variant (B.1.1.529) of SARS-CoV-2: Mutation, infectivity,transmission, and vaccine resistance

- Clinical manifestations and prenatal diagnosis of Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy: A case report

- Lunate dislocation with avulsed triquetral fracture: A case report

- Protein-losing enteropathy caused by a jejunal ulcer after an internal hernia in Petersen's space: A case report

- Eustachian tube teratoma: A case report

- Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in pregnancy: A case report