Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in family clusters: a systematic review

Wen-Liang Song 1 · Ning Zou 1 · Wen-He Guan 1 · Jia-Li Pan 1 · Wei Xu 1

Abstract

Keywords Children · Coronavirus disease 2019 · Family clusters · Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Introduction

Many respiratory infectious diseases show feature of high incidence in winter, and some might break out within families. Children, as a special group due to immature immune system, are more vulnerable to many respiratory infectious diseases compared with their adult family members.For example, during the pandemic of influenza, especially 2009 swine influenza, children are more easily infected, and school children can drive dissemination of influenza virus in the household and community [ 1- 5].

We all pay close attention to coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19) since December 2019, outbreak of a novel respiratory infectious disease, which has cause pandemic and spread around the world [ 6- 8]. The pathogen identified has been named as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [ 8], and World Health Organization has declared COVID-19 a public health emergency of international concern [ 9].

Although people of all ages are susceptible to SARSCoV-2 infection [ 8, 10], compared with pandemic of influenza, there are much more reported cases of adult patients during COVID-19 pandemic [ 6- 8], whereas pediatric patients accounts for a small proportion. Data from Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention showed that among 72,314 reported cases, about 2% of 44,672 confirmed cases of COVD-19 were children aged 0-19 years,and children under age of 10 years accounts for 0.9% [ 11].Data published on 18 March 2020 from Italy reported children accounted for 1.2% of 22,512 Italian COVID-19 cases[ 12]. As for the United States, 1.7% of 150,000 laboratory confirmed COVID-19 cases were children under 18 years[ 13], with only 5.7-20% admitted in hospital and 0.58-2%of them in pediatric intensive care unit.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus can be transmitted via respiratory droplets, even aerosol [ 14, 15]. In the early epidemic period, nearly 90.1% of children showed feature of family cluster [ 16, 17], where children were believed to be infected via close contact with family members [ 10]. Besides, they only received SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid tests if they showed clinical manifestations or there were COVID-19 patients in their family, which is another difference from influenza.

For above reasons, we conduct this study to systematically review the current knowledge of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adults in family cluster and profile characteristics of COVID-19. We aimed to find out differences between children and adults infected with the same virus strain, even to identify probable transmission mechanism within family members.

Methods

Data sources

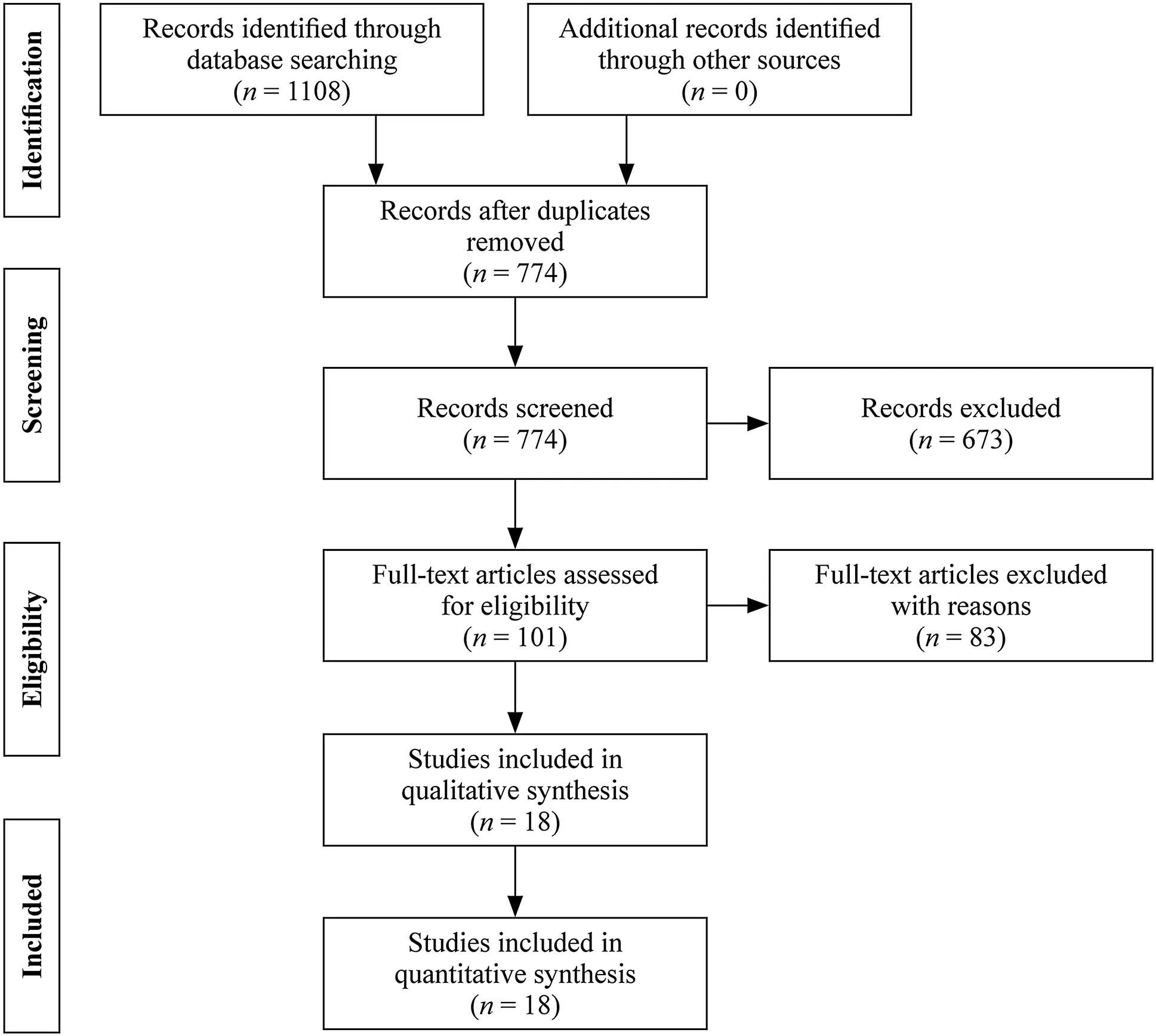

We performed a systematic literature review of PubMed,Web of Science, “ www. cnki. net”, “ www. cqvip. com” and“ www. Wanfa ngdata. com. cn ” on 10th March 2021 to identify papers on COVID-19 family cluster with children and their family members. We use search terms as followings:(2019-nCOV or SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19 or novel coronavirus) and (family cluster or family aggregation). For further relevant studies, the references of selected articles were also identified through manual search. The literature search process is presented in Fig. 1.

Criteria

Inclusion criteria: we included all studies that have reported clinical manifestations, laboratory examinations, chest computed tomography (CT) and nucleic acid test (NAT) in family clusters of COVID-19 including both children (age from 29 days to 14 years) and adults. Exclusion criteria: neonate(younger than 28 days) as well as articles containing insufficient data were excluded.

Data extraction

Two independent assessors (Song WL and Zou N) performed the data extraction with agreement reached by consensus. The following information was extracted from each study for the analysis: age, sex, incubation period,duration of pharyngeal swab NAT-positive period (days),clinical manifestations, laboratory examination and chest CT manifestations.

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of the study selection process

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as medians and interquartile ranges. Categorical variables were described as counts and percentages. Chi-square tests and Fisher exact tests were used for categorical variables as appropriate and Mann-WhitneyUtest was used for comparing median values of non-normally distributed variables. All analyses were conducted with the use of Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS 22.0) software. A two-sidedαof less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Summary of searching results

The search yielded 1108 hints both in English and Chinese.Removing 334 duplicates we identified 774 articles and after screening by criteria we got 18 articles finally, with 12 English articles [ 17- 28] and six Chinese articles (Supplementary Table 1) [ 29- 34].

General clinical information

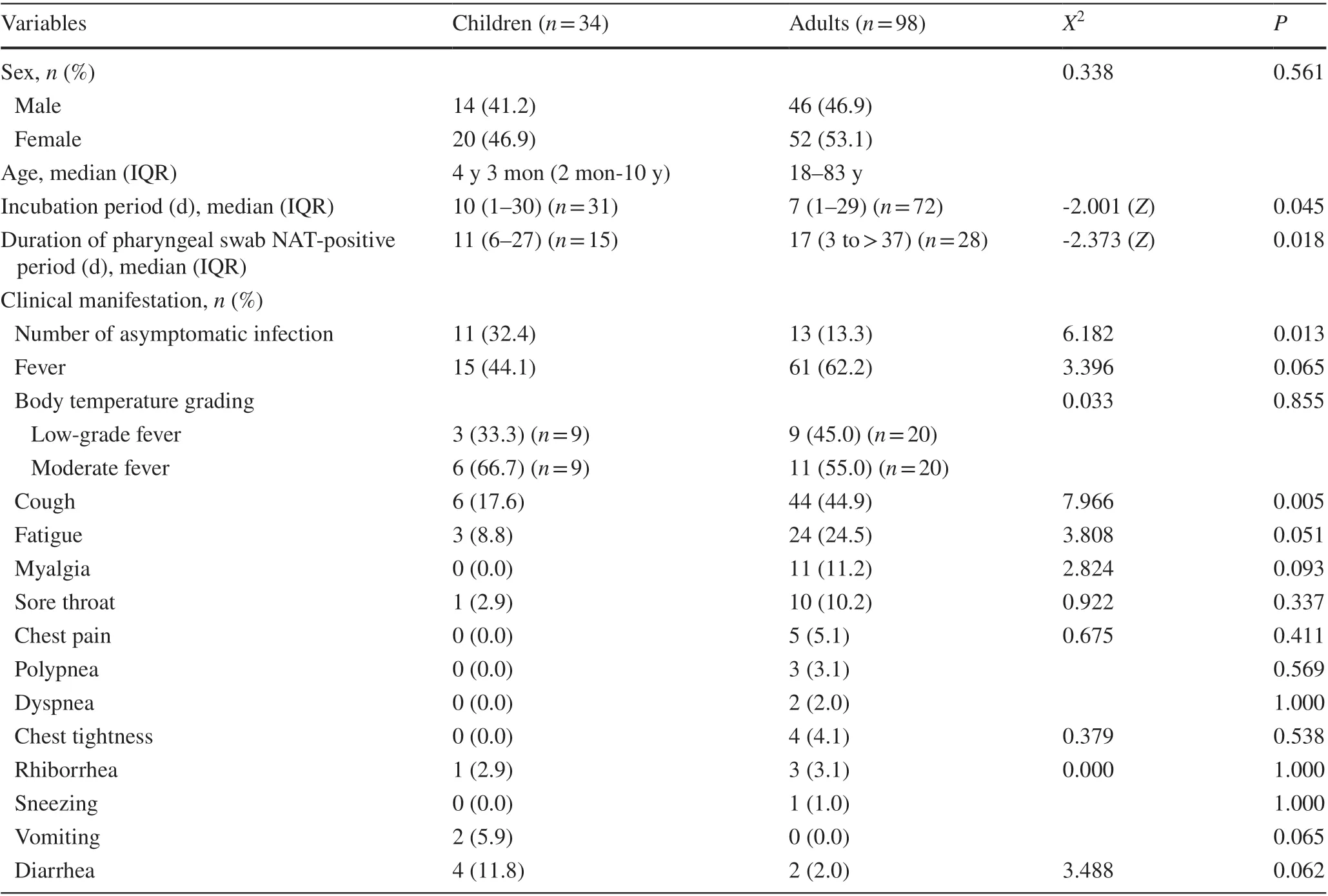

There were 28 families reported in the 18 articles. A total of 132 patients were reported, including 34 children and 98 adults, with a mean number of one (range 1-3) child per family, and they were diagnosed as COVID-19 in January and February, 2020, which was the early epidemic period of COVID-19. The ages of children were from 2 months to 10 years (median age 5 year 3 months) with a male to female ratio of 14:20, and ages of adults were 18-83 years with a male to female ratio of 46:52. In 27 (27/28, 96.4%) families adults were first diagnosed as COVID-19 previous to children, and in only one family, the first diagnosed patient was a child [ 19], whereas the mother being the infectious source,showed negative NAT for a long time until diagnosed. The general information was showed in Table 1.

The top 3 symptoms of children were fever (15/34,44.1%), cough (6/34, 17.6%) and diarrhea (4/34, 11.8%),whereas for adults were fever (61/98, 62.2%), cough (44/98,44.9%) and fatigue (24/98, 24.5%). Besides, children showed a higher proportion of asymptomatic infections (11/34,32.4%) than adults (13/98, 13.3%) with statistical significance (P< 0.05). In addition, adults showed various symptoms besides previous mentioned as following, 11 (11/98,11.2%) cases with myalgia, 10 (10/98, 10.2%) cases with sore throat, 5 (5/98, 5.1%) with chest pain, 3 (3/98, 3.1%)cases with polypnea, 2 (2/98, 2.0%) cases with dyspnea, 4(4/98, 4.1%) cases with chest tightness, 3 (3/98, 3.1%) with rhiborrhea, 2 (2/98, 2.0%) with diarrhea and 1 (1/98, 1.0%)case with sneezing, compared with children showing less symptoms including 3 (3/34, 8.8%) cases with fatigue, 4(4/34, 11.8%) cases with diarrhea, 2 (2/34, 5.9%) cases with vomiting and 1 (1/34, 2.9%) case with rhiborrhea (Table 1).Furthermore, from limited data of body temperature records,both group showed Tmaxranging from 37.3 to 39 ℃ and no statistical difference in grade of fever between them. To be noted, children patients showed a longer incubation period(10 days) but a shorter duration of positive pharyngeal swab NAT results (11 days) than adults (7 and 17 days, respectively) with statistical significance (P< 0.05). In addition,there were four pediatric cases, whose duration of positive pharyngeal swab NAT duration ranging from 7 to 27 days,comparing with positive anal swab NAT duration lasting more than 28 days [ 26, 27, 29].

Laboratory examination characteristics

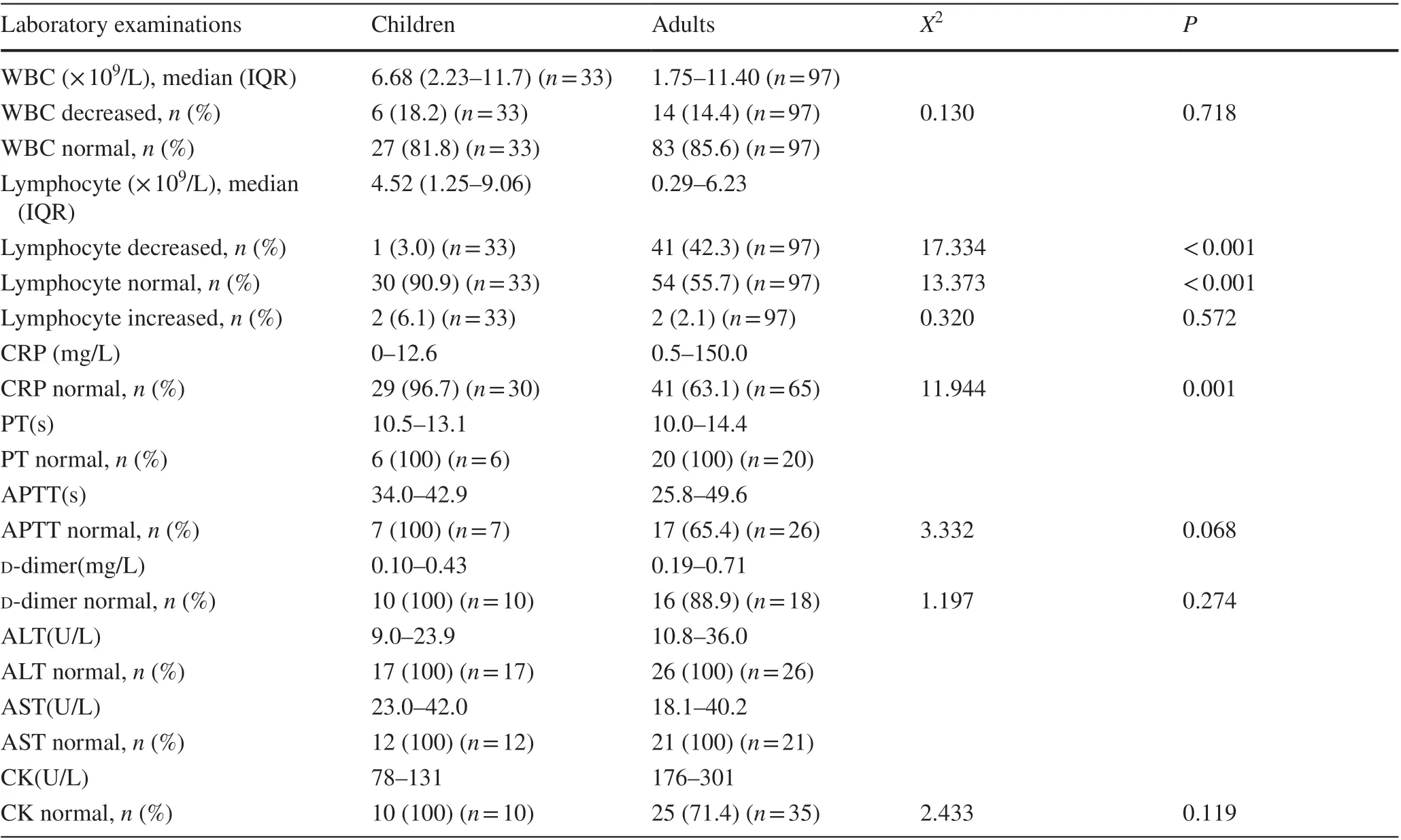

Children and adults of family clusters underwent tests of blood cell analysis, C-reactive protein (CRP), biochemical indexes and evaluation of organ injury severity. Leukocytedecreased in 6 (6/33, 18.2%) cases of children and 14 (14/97,14.4%) cases of adults, and remained normal value for 27(27/33, 81.8%) cases and 83 (83/97, 85.6%) with no statistical difference, respectively (P> 0.05). However, 1 (1/33,3.0%) case of children showed lymphopenia while 41 (41/97,42.3%) cases of adults did, and lymphocytes were normal for 30 (30/33, 90.9%) cases of children and 54 (54/97, 55.7%)cases of adults, respectively, with statistically significant difference (P< 0.05). There were 41 (41/65, 63.1%) cases of adults with normal CRP with a percentile of 63.1% compared with 29 (29/30, 96.7%) case in children (P< 0.05). All children showed normal prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), D-dimer, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase and creatine kinase (CK),which was the same for adults except nine cases of abnormal APTT, two cases of abnormal D-dimer and 10 cases of abnormal CK. Details were shown in Table 2.

Table 1 General clinical characteristics of children and adults in family clusters of coronavirus disease 2019

Chest CT manifestations

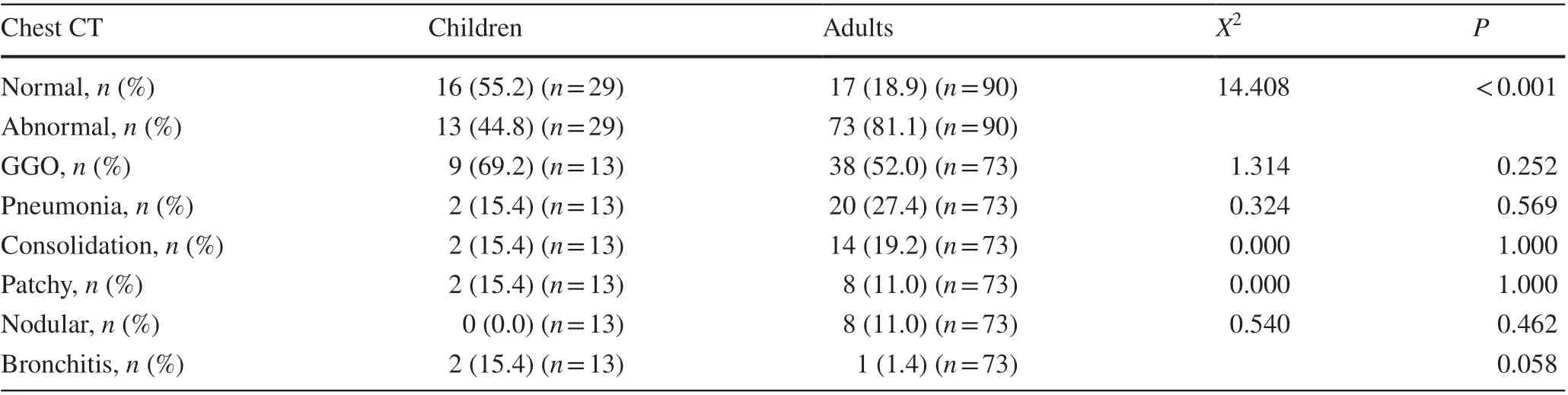

Among 29 cases of children and 90 cases of adult patients who performed chest CT scan, 13 (13/29, 44.8%) cases of children and 73 (73/90, 81.1%) cases of adults showed abnormal image results, with statistical significance(P< 0.05). Furthermore, ground-grass opacity (GGO)change was the leading feature both for children and adults with a percentile of 69.2% (9/13) and 52.0%(38/73), respectively, followed by pneumonia change,consolidation, patchy and nodular changes, and bronchitis, whereas there was no statistical difference between two groups (P> 0.05). Details were shown in Table 3.

Furthermore, we defined pneumonia based on the changes of CT regardless of symptoms and classified clinical types according to diagnostic guidelines in China for children and adults, respectively [ 35, 36]. There were equally five asymptomatic children and seven adults with abnormal CT diagnosed as pneumonia. Besides, according to their clinical manifestations, lab examinations and CT, 16 cases of children and 17 cases of adults were grouped as mild type, with the left 13 cases of children and 73 cases of adults grouped as common type.

Discussion

This systematic review showed that there were more adult patients infected with COVID-19 than children in family clusters of COVID-19. It might be due to most literaturesinvolved in this review reporting data from China and because in a family, there were more adults than children as an objective fact that under one child policy in China, most families constitutes of one child, two parents and four grandparents. Besides, almost all family members from respective family cannot avoid being infected with SARS-CoV-2 indicates that it is a highly contagious disease and all people are susceptible [ 8, 10]. In addition, close contact or family cluster is the main mode of transmission. It can provide some evidence for more adult COVID-19 to some extent.

Table 2 Blood routine test characteristics of children and adults in family clusters of coronavirus disease 2019

Table 3 Chest computed tomography manifestations of children and adults in family clusters of coronavirus disease 2019

It is worth of attention that being exposed to the same circumstance in the same family, both children and adults infected by the same virus strain, although there were many common features shared by them, there were also different aspects between two groups. Fever and cough are the main onset clinical manifestations of COVID-19 for both children and adults in family clusters, which is consistent with previous publications [ 6- 8, 10]. In addition, both children and adults showed mild type and common type, without severe,critical type or death cases. However, pediatric patients showed lower proportion of symptoms, such as fever (15/32,46.9%) and cough (6/32, 18.8%), compared with adults(56/89, 62.9% and 39/89, 43.8%, respectively), as well as fewer symptoms, such as fatigue, myalgia, sore throat, chest pain, which were more common for adults [ 6, 8], although there were more cases of children with vomiting and diarrhea, which may be due to immature digestive system. On the other hand, proportion of asymptomatic infection was higher in children than adults with statistical significance(P< 0.05). Furthermore, the disease seems milder for children when comparing the proportion of pneumonia between children and adults (48.1, 82.7%, respectively,P< 0.05). As the pathogen of COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2 gains entry into epithelial cell via angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)receptor and transmembrane serine protease 2 [ 37- 41].There has been evidence that number of ACE2 receptors are significantly lower in children than in adults [ 41], which may be the primary reason why children have fewer clinical symptoms, less severe disease and lower proportion of pneumonia. Besides, difference in maturity, functionality or affinity of ACE2 receptor between children and adults may account for these discrepancies to some extent, which needs further research. On the other hand, a few children showed onset manifestations of gastrointestinal tract, such as vomiting and diarrhea [ 26], which were atypical symptoms for respiratory infectious diseases. ACE2 is expressed in many organs, not only in respiratory system, but also in digestive system, urinary system, neurological system and circulatory system [ 39, 42- 48]. Maybe there is discrepancy in distribution of ACE2 receptor in different organs, or different functions of ACE2, which may account for various manifestation of COVID-19. However, the hypothesis needs more studies to prove.

Index case was defined as patient in the household cluster who first showed symptoms. From this analysis, we found that almost all families have adult as index case except one with child [ 19]. Furthermore, the infectious source of each family was adult and can be asymptomatic or later-onset than other family members [ 19, 24, 30]. In addition, there were family members with onset manifestation of no symptom,among whom there were asymptomatic infection and even pneumonia, which may be neglected without SARS-CoV-2 NAT and chest CT examination. To be mentioned, there was an index case of adult with asymptomatic infection throughout his illness course and only showed SARS-CoV-2 NATpositive [ 30], and there was only one child in this family, who was 2.5 years and showing cough, normal white blood cell(WBC) and lymphocyte 10 days after contacting with the index case. Besides, for the family in which child being the index case, she stayed at home all the time under the condition of prevention of epidemic situation and schools were closed.She was actually infected by her mother, who returned from Wuhan, the epidemiological area, and regarded as the infectious source for this family. They received NAT on the same day, but the mother showed negative result and had later-onset manifestation and long NAT negative period [ 19]. Therefore,it indicates that SARS-CoV-2 may be contagious during incubation and asymptomatic patients can transmit the virus.

Although the incubation period for children and adults both varied from 1 to 30 days, it was longer for children with median time of 10 days than adults with 7 days (P< 0.05).However, this period has been assessed based on the most probable contacts with documented cases but other sources of exposition might be not explored especially by asymptomatic patients. This assessment is not so sure. Comparing to 54% of transmission clusters identifying children as index case in influenza [ 49], only 3.6% of family in this review identified children as index case of COVID-19, which may be due to longer incubation period of children for COVID-19 than adults to some extent [ 50]. During early epidemic period, schools were closed and children stayed at home. So it is not surprising for children to be later detected. Besides,from limited data of duration of pharyngeal swab NAT-positive period, we found children undergoing shorter course than adults (11 days and 17 days, respectively,P< 0.05).SARS-CoV-2 NAT with throat and nose swabs or lower airway secretion were the gold standard for the diagnosis of COVID-19 [ 35], and patients can be released from quarantine after disappearance of symptoms and two consecutive negative results of NAT. Somehow, four pediatric cases showed duration of positive pharyngeal swab NAT ranging from 7 to 27 days, while their anal swab NAT showed positive duration lasting more than 28 days. Three children showed common characteristics of fever and gastrointestinal symptoms, such as vomiting and diarrhea. Besides, their anal swab NATs were still positive for a long time even after disappearance of symptoms and negative results for pharyngeal swab NATs. To be mentioned, one child was asymptomatic and positive duration of her nasopharyngeal swab NAT lasted 22 days, whereas her fecal samples NAT showed positive more than 100 days. Therefore, there is still debate on infectivity of feces containing SARS-CoV-2 and time of quarantine.

In this review, we found that pediatric patients showed almost all normal lab examination results, except for 6 (6/33,18.2%) cases with decreased WBC and 1 (1/33, 3.0%) case with increased CRP, whereas compared with adult patients,proportion of decreased WBC showed no statistical significance. In addition, there were more adults with lymphopenia and increased CRP than children with statistical significance(P< 0.05). Lymphopenia reflects consumption of lymphocyte by SARS-CoV-2 and was related to severity of disease [ 6, 7]. Here, it indicates that lymphocytes in children were not as consumptive as adult patients. The difference of increased CRP, an inflammation marker, may be related to different immune status or more intense inflammation reactions in adults. Somehow, the biochemical indexes that reflect organ functions were at large normal both for children and adults. Our review studied the articles published from January to September, 2020, with cases diagnosed in January and February, 2020, and it seems children showed milder inflammation in the early epidemic period of COVID-19.However, with the SARS-CoV-2 variants evolving each day,these data on children may change according to the variants.

As for image of lung, here we found number of abnormal CT in children was fewer than adults, which indicates children seems less susceptible to be infected with pneumonia. Consistent with previous studies [ 6- 8, 51- 55],GGO changes were the dominant features of chest CT for both children and adults in our study. However, other changes, such as consolidation, pneumonia-like change,patchy and nodular changes, were less common seen in children compared to adults [ 53- 55]. These may reflected milder disease of children to some extent. To mention,although CT played an important role to detect patients with COVID-19 earlier as a diagnostic method because of lack of SARS-CoV-2 NAT material and low positive rate of NAT in the early epidemic period, these features of CT were not specific for COVID-19 exclusively because they can also be seen in pneumonia caused by other virus[ 56- 59]. With widely used NAT and improved method,we can now quickly and accurately make diagnosis of patients with COVID-19, and chest CT can show patterns of lung abnormalities and reflect clinical condition to some extent.

There is another key point to be mentioned that, all the cases reported in these articles were diagnosed in January and February, 2020, the early epidemic period of COVID-19, during which period the first diagnosed patient in family either returned from epidemic area or had contacts with COVID-19 patients. However, during that period, children were limited to family environment, and school and kindergarten closure further confined children activity. Besides,special physical and social features of children, such as lack ofindependence and need of parents’ company, make them less exposure to out-family environment, and social activity involvement for children reduced. Therefore, children of COVID-19 were infected by adults from their family in family clusters.

With increasing cases, there are also reports of children with multi-system inflammation syndrome [ 60, 61],manifested as fever more than three days, multi-system affected and elevated inflammation markers. It is another severe condition caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection, may be due to immune system disorder, and may occur in children with fever or asymptomatic in the early period after two weeks post SARS-CoV-2 infection [ 62]. Besides,some skin changes may also appear after SARS-CoV-2 infection [ 63], which may give us clues for early diagnosis. Although these articles were not included in our review for not meeting standards, these information gave us new aspects of SARS-CoV-2 infection and we should pay attention to children with fever or asymptomatic in the early period.

There were several limitations for our study. First,although we searched huge amount of articles, most of them reported data from adults or children independently, leading to a small size of eligible studies based on our including criteria. Second, there was lack of data concerning viral load for us to compare difference between children and adults,which can give a more detailed profile of COVID-19 of family clusters.

In conclusion, this review profiles a comprehensive characteristic of COVID-19 of family clusters. In the early epidemic period of COVID-19, children of COVID-19 were infected by adults from their family showing characteristics of family clusters. However, same virus strain caused milder disease in children compared with their family members according to clinical manifestations, lab test results and chest CT changes.

Supplementary InformationThe online version contains supplementary material available at https:// doi. org/ 10. 1007/ s12519- 021- 00434-z.

AcknowledgementsThe author thank all the team members of this review for corporation.

Author contributionsSWL contributed to conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, and original draft preparation. ZN contributed to methodology and visualization. GWH and PJL contributed to software and data curation. XW contributed to conceptualization,validation, review and editing, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

FundingThis research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81771621), and the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (No. 2019JH8/10300023).

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approvalThis work was retrospectively collecting information from articles published. Not required for a systematic review.

Conflict of interestNo financial or nonfinancial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.Data availability The datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

World Journal of Pediatrics2021年4期

World Journal of Pediatrics2021年4期

- World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- Increased asprosin is associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children with obesity

- Mosaic trisomy 12 diagnosed in a female patient: clinical features,genetic analysis, and review of the literature

- Increasing prevalence and influencing factors of childhood asthma:a cross-sectional study in Shanghai, China

- Responsible genes in children with primary vesicoureteral reflux:findings from the Chinese Children Genetic Kidney Disease Database

- Pediatric interfacility transport effects on mortality and length of stay

- Impact of probiotics supplement on the gut microbiota in neonates with antibiotic exposure:an open-label single-center randomized parallel controlled study