Extent, reasons and consequences of off-labeled and unlicensed drug prescription in hospitalized children: a narrative review

Wasim Shuib · Xin-Yin Wu · Fang Xiao

Abstract

Keywords Licensed medicines · Off-label prescribing · Pediatrics · Unlicensed prescribing

Introduction

In the 1960s several of today’s drugs, which are considered essential human drugs, were readily available over the counter without prescription. Essential drugs herein refers to medicines that satisfy the priority health care needs of the population [ 1]. Moreover, drugs could be utilized in humans based on experiments exclusively conducted on experimental animals [ 2]. Following a reported link to congenital disabilities caused by then over-thecounter available thalidomide in the early 1960s, governments and international organizations began introducing strict human drug regulations and monitoring to ensure patients’ safety, drug quality, and effectiveness. Many countries today have dedicated drug regulation authorities [ 1, 2].

To ensure safety, quality and effectiveness, drug regulatory authorities assess drugs presented by pharmaceutical companies through preclinical testing, clinical trial phases involving volunteering human subjects, and review of results before granting a marketing license for public human consumption, as a licensed drug [ 3].However, regarding pediatrics, the number of clinical trials used to enable the authorization of adequate pediatric-use licensed drugs as compared to adult population trials is limited [ 4, 5]. This limitation was attributed to several reasons, including the smaller pediatric population as compared to the adult population. Apparently, to ensure a legitimate consenting process for participating in clinical trials, the pediatric population is subject to a number of obstacles [ 6]. One of the issues is the ethical scheme. This is crucial for consenting people to participate in clinical trials. Another obstacle could be that the pediatric population has different pharmacokinetics.This means their absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination of drugs is not as robust due to their delicate body physiology as compared to adults [ 7, 8].The overall effect is to limit the number of pediatric licensed drugs, which is the main reason behind the current storm of unlicensed and off-label prescriptions in the pediatric population [ 9, 10].

Unlicensed drug is defined as prescription of a medicinal product for human use, with no granted marketing authorization by the countries’ licensing authority. The extent of unlicensed prescriptions has been reported to range from 0.3 to 35%, which severely affects the pediatric population compared to other age groups [ 11, 12]. Despite the variety of categorization based on an individual country’s criteria, as a whole the prescription of an unlicensed drug is not deemed illegal [ 13]. Moreover, a licensed drug could also be used outside its authorized age group of use, indication, dosage,route of administration, or frequency; this practice is referred to as off-label prescription and is also a legal act with a global reported prevalence ranging from 36.3 to 97.0% [ 14].

It follows that off-label and unlicensed prescriptions in the pediatric population could be beneficial because there are currently limited authorized drugs for this population.On the other hand, the practice could pose a big concern regarding patients’ safety. Therefore, we aimed to explore the extent, reasons, and consequences of off-label and unlicensed drugs in hospitalized pediatric patients, by conducting a narrative review of the literature.

Methods

This review was written based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA)but was designed to be a narrative review of the literature.The aim was to determine the extent, reasons, and consequences of off-label and unlicensed drugs in hospitalized pediatric patients including admitted children in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) or pediatric intensive care unit(PICU) and in the general pediatric ward.

Search strategies

We systematically searched PubMed, EMBASE, SCOPUS, Web of Science and Google scholar from between 1990 and 2020 in which the last search was conducted on 5 February 2021. We performed advanced search in all the databases using medical subject headings (MeSH) and key term depending on the database. In PubMed database, the search strategy: [“off-label use” (Mesh) AND “prevalence”(Mesh)] AND “child” (Mesh) was built using keys like offlabel use AND prevalence AND child with Boolean operators. The search strategies used in the other databases are as follows: (“prevalence”/mj AND “off label drug use”/mj OR“unlicensed drug use”/mj) AND “child”/mj for EMBASE,prevalence AND off AND label AND drug AND use OR unlicensed AND child OR pediatrics AND treatment OR therapy for SCOPUS, (TI = prevalence AND TI = off label drug use OR TI = unlicensed AND TI = child) AND language: (English) AND document types: (article) for Web of Science and prevalence AND off label drug use OR unlicensed AND child forGoogle search.

Eligibility criteria

We included studies with the following inclusion criteria:(1) observational studies in design; (2) target population was hospitalized pediatric patients whether admitted in the intensive care unit or general ward; (3) study reporting the prevalence of off-label, unlicensed prescriptions or both; and(4) published in English.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies with the following criteria: (1) review articles; (2) duplicate publications; (3) articles not in full text; (4) articles not written in English; (5) studies based on mixed participants; (6) study participants not children; and(7) studies outside of study setting.

Results

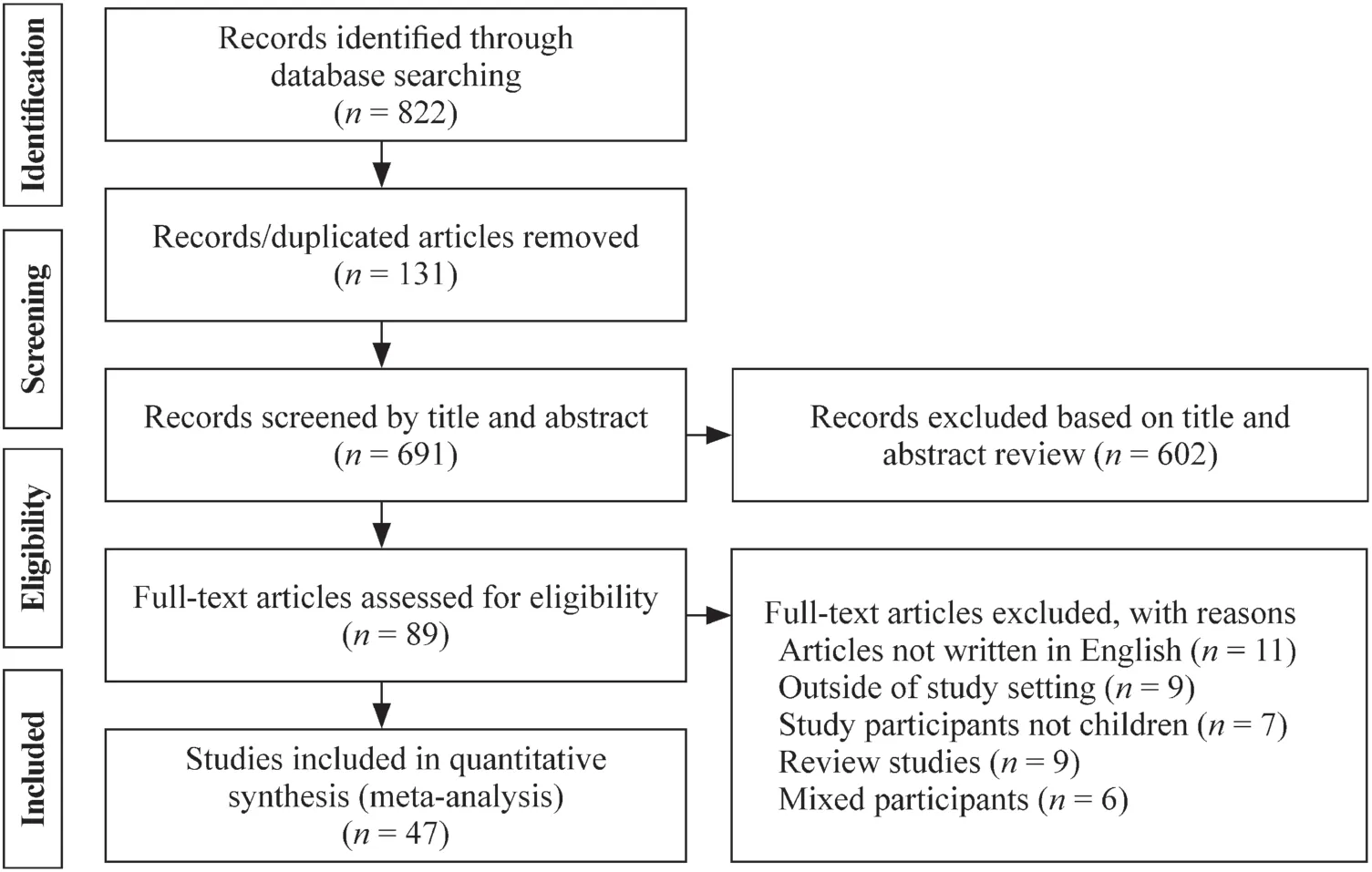

A total of 822 articles were identified using electronic search engines and strategies. Among these articles, 131 were dropped as duplicates and 691 articles remained for further screening.The evaluation of title, full text and abstract screening resulted in the exclusion of an additional 602 articles. Therefore, a balance of 89 full-texts of studies was screened for eligibility criteria and other parameters that are not compatible with the review objectives. The full texts of 89 studies were reviewed for eligibility, and 11 studies were excluded from the analysis for not being English studies and nine studies were excluded for not reporting on the prevalence of the outcome (unlicensed and off-label prescriptions). In addition, seven studies were participants not children, nine studies were reviews, and six studies included mixed participants (adult and children). Therefore, a total of 47 studies were included in this review (Fig. 1).

This review summarized the most common off-labelled and unlicensed drugs prescribed in the selected studies(Table 1). Our review consisted of 25 studies from the Pediatric ward (Table 2). When comparing the PICU and NICUin our review, 13 studies were included in NICU (Table 3)and only five studies in PICU (Table 4). In Tables 3 and 4, the majority (90%) used prospective studies as study designed. We were able to include only four studies [ 23, 38,57, 58] on the neonatology ward category. Of these studies, only one was conducted in Saudi Arabia; the rest were conducted in Europe (Slovak Republic, France and Estonia).While two studies were cross sectional, the other two were prospective studies (Table 5).

Fig. 1 PRISMA flow diagram summarizing the study selection process of included studies.PRISMA preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis

The extent of off-label and unlicensed drugs among hospitalized children

The proportion of off-label prescriptions ranged from 7.4% (Italy) to 99.5% (Brazil). [ 32, 47]. The proportion of unlicensed prescriptions ranged from 0.1% (Estonia)to 72.4% (Pakistan) [ 26, 57]. Moreover, the combined proportions of off-label and unlicensed prescriptions comprises four studies. These ranged from 44.5% (Malta)to 87.7% (Germany), Turkey 62.3% and Korea Republic 84.6% [ 20, 33, 34, 51].

One study [ 24] compared the extent of off-label and unlicensed prescription between countries (China and USA).A study [ 33] compared the proportions in China and USA.Regarding off-label prescriptions, a percentage of 15.87%and 46.5% were recorded in China and the USA, respectively, whereas the proportions of unlicensed drugs were seemingly higher in China with 74.1% compared to 22.0%recorded in the counterpart. Another study considered analysis on seasonal variation of the extent of these sorts of drug usage. During the winter season (August), 27% of prescriptions were classified as unlicensed and 44.6% as off-label;during summer season (January), 29.6% as unlicensed and 45.1% as off-label [ 9].

Regarding pediatric patients in the intensive care unit,a study from Israel [ 22], reported a seemingly higher proportion of prescriptions in neonatal population compared to 43.8% in the pediatric population for both off-label prescriptions (64.8% versus 43.8%) and unlicensed prescriptions (5.9% versus 3.4%).Among the 38 included studies that provided information on the categories of off-label prescription, outside age range prescription (41.2%) was the most frequent category,followed by indication (26.5%) and dosage (20.6%) (Fig. 2).The pediatric population is, therefore, at an increased risk of consequences from off-label prescription, urging prompt global attention and response. The response should involve fostering clinical trials for pediatric population by pharmaceutical companies. Figure 3 illustrates the proportions of studies included in our review that reported mostly prescribed categories of drugs according to anatomical therapeutic chemical classification [ 59]. The majority (34.2%) of off-label prescription drugs were not effective for systemic use. Moreover, drugs belonging to the nervous system category were mostly (21.1%) prescribed as unlicensed.

Reasons and justification of the off-label or unlicensed prescription practice

A total of 28 (59.57%) studies reported various reasons that led to the unavoidable practice of prescribing off-label and unlicensed drugs as shown in Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5. The most common reason was lack of information, specifically for pediatrics on the drug information leaflets. Other reasons included lack of suitable formulation for pediatrics, imported medicines not authorized inthe country of administration and extemporaneously prepared drugs. For example, there are changes in the drug formulation authorized but this takes time for prescribers to adopt, and also a time during which previously correct drug formulations deem off-label [ 39]. Another example is that the information regarding newly formulated drugs in the product information leaflets may seem outdated in drugs that are already in the market [ 54].

Table 1 The most common off-labelled and unlicensed drugs prescribed

Table 1 (continued)

Consequences of off-label and unlicensed drugs

Among the included 47 studies, only 8 (17.02%) (Netherlands, Malaysia, Ireland, Korea Republic, Indonesia,Australia and two studies from Brazil) had reported consequences of off-label and unlicensed drug prescriptions,ranging from mild side effects (e.g., skin reaction) [ 44] to the fatal outcomes, such as renal failure [ 19]. Apart from the aforementioned consequences that were more direct to patients’ health (i.e., patients’ consequences), two studies[ 15, 46] reported other consequences which were indirect and impacted prescribers leading to medical legal-issues(i.e., prescribers’ consequences).

Discussion

In the last decade, there has been a surge in concerns regarding off-label and unlicensed drug prescriptions in the pediatric population, mainly due to fewer clinical trials done in this population as compared to the adult population [ 3]. Though not an illegal act, off-label and unlicensed prescriptions require consideration of safety and consent, after a thorough assessment of the benefit-risk ratio. Recently, the use of off-label drugs and unlicensed prescriptions of drugs in children is at an increasing rate. Despite the implemented legislative regulations, the approved pediatric labeling is not efficient for pharmaceutical industry [ 60]. Currently, national governments are required by the World Health Organization to establish and maintain regulatory authorities for medicines[ 61].

We reviewed published literature from the last three decades to provide an up-to-date summary of the extent, reasons, and consequences of off-label and unlicensed drugs in hospitalized pediatric patients. The proportion of off-label prescriptions ranged from 7.4 to 99.5%. Comparing our review with the previously published literature, Mouliset al. [ 14] and Gore et al. [ 12] reported that the ranges were 36.3-97.0% and 9-78.7%, respectively. These are quite narrower than the range reported in our review. Magalhães et al.[ 62] also showed a similar more restricted range as compared to our study (i.e., 12.2-70.6%). On the other hand,Balan et al. [ 63] reported a more extensive range of off-label prescriptions compared to our study (i.e., 1.2-99.7%). All the reported ranges are considerably wide. We believe that the reasons for the wide ranges are due to high heterogeneity between the reviewed studies that could be attributed to different opinions among prescribers depending on their experience and drug availability in their local settings. The evidence, as shown in our study, is that different countries have different extents of off-label prescription [ 22, 33].Moreover, drugs information evolves over time with newer drug formulation emerging as technology evolves. This means that studies published in different times could have different definitions of off-label prescription, even for the same drug. The finding that different extents of off-label prescriptions were prescribed in winter and summer times could be attributed to different disease patterns in the two seasons.For example, winter season is likely to have an increased number of upper and lower respiratory illnesses compared to summer season, meaning more respiratory system drug prescriptions in the winter than summer.

Table 2 Summary of study characteristics of pediatric ward included in our review

Table 2 (continued)

Table 3 Summary of study characteristics of NICU included in our review

Table 3 (continued)

Table 4 Summary of study characteristics of PICU included in our review

Table 5 Summary of study characteristics of neonatology ward included in our review

Fig. 2 The proportion of studies reporting most frequent off-label prescription categories

In our review, the most frequent category of off-label prescription was prescription outside the age range. Authors believe the reasons to be attributed to the fact that fewer clinical trials have been done in the pediatric population due to ethical issues regarding this smaller and fragile population as compared to the adult population [ 6]. This finding, however,contradicts those reported by Tukayo et al. [ 15], Kouti et al.[ 10], Dornelles et al. [ 9] and Costa et al. [ 19] who reported,respectively, that the most frequent categories were indications, dosage, formulation and administration frequency. The reasons could be attributed to heterogeneity among reviewed studies. Even though our review included hospitalized pediatric patients, other studies involved intensive care unit patients while others involved general ward patients. Intensive care unit patients are regarded to be sicker with probably more prescriptions as compared to general wards’ patients. Moreover, different hospitalized patients have different diagnoses that could mean different drug prescriptions, frequencies, formulations,dosages, and routes of administrations.

The proportion of unlicensed prescriptions ranged from 0.05 to 74.14%. This range is wider that those reported inthree previously published studies [ 12, 14, 62], which were 0.3-35%, 18.6-40.2%, and 0.2-47.9%, respectively. Generally, all of these ranges are considerably wide. Besides high heterogeneity among the reviewed studies, variation in the definition of unlicensed drugs among different countries could be another potential reason for the differences. For example, the same drug can be licensed in one country, but not licensed in another.

Fig. 3 Proportions of studies that reported mostly prescribed categories of drugs according to anatomical therapeutic chemical classification

Although not reported in the majority of included studies,the most commonly reported reason for off-label prescriptions was a lack of information specifically for pediatrics on the drug information leaflets. This was not entirely the case as Costa et al. [ 19], who reported the reason to be a delayed adaptation to newly introduced drug/drug formulations, in Brazil. Prescribers, pharmaceutical companies, and drug authorities should collaborate to tackle the barriers mentioned above and others, such as lack of suitable formulation for pediatrics, imported unlicensed drugs, and extemporaneously prepared drugs.

Only a few studies reported the consequences of off-label and unlicensed prescriptions. These could be bearable or very serious, including deaths. However, at present, it is evident that the pediatric population is a “therapeutic orphan”[ 64, 65]. Until adequate trials and authorized drugs for the pediatric population become available, unlicensed and off-label medication should not be abruptly banned in this population. The practice should, instead, be closely monitored while pharmaceutical companies, prescribers, and drug authorities collaborate to foster trials and to authorize adequate drugs for this population.

Study limitations and strengths

Our study had several limitations that originated from the study level and review level. At the included study level,different studies were broadly different from one another in terms of participants’ demographic characteristics, different study methodologies, and studies from diverse countries across the globe. Hawthorne effect could also have impacted prescribers’ responses [ 34]. At the review level,our study design is a narrative review with no quantitative data. However, we believe that this review could contribute to providing a broad picture on this topic by qualitatively summarizing evidence on the extent, reasons, and consequences of off-label and unlicensed drugs prescription as quantitative strategies like meta-analyses might not be the optimal option to reach to objectives of this review.Despite several previously published literature on this review’s topic, our review currently considers pediatric population as a “therapeutic orphan” therefore does not discourage off-label or unlicensed prescriptions, but offers recommendations for closely monitoring the practice to prevent and/or mitigate adverse consequences, until when there are adequate authorized drugs for the population in the market.In conclusion, impacting patients’ safety and prescribers’ practice, off-label and unlicensed prescription is extensive and requires progressively meditative interventions.However, the pediatric population is currently a “therapeutic orphan”. Unless adequate pediatric clinical trials and licensed drugs become available, off-label and unlicensed drug prescription should not be discouraged but should be promoted in an organized manner. We therefore encourage prescribers to follow our recommendations to (1) regularly review and timely update the locally authorized drug database; (2) consult the locally authorized drug database or drug information leaflet before prescription; (3) consider prescribing an off-label or an unlicensed drug only if absolutely necessary after discussion with patients’ parent/legal guardian on risks and benefits; (4) signing consent form;(5) monitoring the patient closely and preparing to mitigate adverse reactions after an off-label or unlicensed drug prescription, together with proper documentation and submission of the report to the country’s drug authority.

AcknowledgementsWe acknowledge assistance in the PubMed search,from Dr. Joel Swai (ORCID: 0000-0001-5363-3977); Department of Nephrology and Rheumatology, The Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, China.

Author contributionsSW contributed to study designing, data search,data extraction, and manuscript drafting. WXY contributed to data search, data extraction, and manuscript drafting. XF contributed to data extraction and manuscript drafting. All authors revised the intellectual content of the manuscript critically, and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

FundingNone.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approvalNot needed.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Data availability Not applicable.

World Journal of Pediatrics2021年4期

World Journal of Pediatrics2021年4期

- World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- Increased asprosin is associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children with obesity

- Mosaic trisomy 12 diagnosed in a female patient: clinical features,genetic analysis, and review of the literature

- Increasing prevalence and influencing factors of childhood asthma:a cross-sectional study in Shanghai, China

- Responsible genes in children with primary vesicoureteral reflux:findings from the Chinese Children Genetic Kidney Disease Database

- Pediatric interfacility transport effects on mortality and length of stay

- Impact of probiotics supplement on the gut microbiota in neonates with antibiotic exposure:an open-label single-center randomized parallel controlled study