Intraoperative monitoring of the recurrent laryngeal nerve in surgeries for thyroid cancer: a review

SR Priya, Srinjeeta Garg, Mitali Dandekar

1Head Neck Surgery, Homi Bhabha Cancer Hospital and Research Centre, Visakhapatnam 530053, India.

2Head Neck Surgical Oncology, Tata Memorial Centre, Mumbai 400012, India.

3Head Neck Surgical Oncology, Paras Cancer Centre, Patna 800014, India.

Abstract Intraoperative nerve monitoring (IONM) has evolved into an objective tool not only for the identification but also for the preservation and prognostication of function of the recurrent laryngeal nerve in thyroid surgeries. Technical improvements have resulted in the increasing incorporation of IONM into operating rooms around the world. The importance of adherence to recommended standards is also recognized as being vital in optimizing the efficacy of IONM. The advent of continuous IONM has made real-time nerve monitoring possible, thus providing the surgeon with an ally in difficult surgeries. Additionally, as thyroid surgeries are evolving into remote access and minimally invasive procedures, so also is the applicability of IONM. This review focuses on the use of IONM for nerve monitoring in thyroidectomies for neoplastic conditions while discussing the rationale, technique, and interpretation of findings and their implications.

Keywords: Intraoperative nerve monitoring, thyroidectomy, recurrent laryngeal nerve, electromyography, vagus nerve

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of total thyroidectomies performed for thyroid cancers in major centers across the globe has increased over the years, thus increasing the number of recurrent laryngeal nerves (RLN) at risk[1]. Injury to the RLN and consequent temporary or permanent palsy has significant implications on quality of life[2].Patients at high risk for RLN palsy include those with thyroid malignancies, especially invasive thyroid cancers and bulky central compartment nodes[3]. Patients undergoing surgeries for recurrent disease and those undergoing completion surgery are also at a greater risk for RLN injury and permanent palsy[4]. Even though a number of palsies are temporary and many of these patients recover after a variable period[2,5,6], any means of minimizing this risk should be considered crucial, considering the negative impact RLN injury has on quality of life with symptoms such as hoarseness, dysphagia, and stridor[7]. The morbidity is particularly severe when the palsy is bilateral[8].

Intraoperative nerve monitoring (IONM) is emerging as one such tool that could be a means of reducing the incidence of this morbidity. While there can be no substitute for an inside-out familiarity with the anatomy of the thyroid gland or of experience in these procedures, the IONM is a corroborative method and useful adjunct for nerve identification, preservation, and prognostication of function in thyroid and parathyroid surgeries.

Subsequent to technological advances, IONM apparatuses are now more compact and easily incorporated into the operating room environment[9]. However, the essentialities such as system setup, anesthesia protocol modifications, and negotiation of the learning curve by the surgeon(s) as well the anesthetist(s)and neurophysiologist remain the same[10].

TYPES OF INJURIES TO THE RLN DURING THYROIDECTOMY

Since the RLN lies in close approximation to the thyroid gland, a wide array of maneuvers can injure the RLN. However, only about 14% of these injuries are visible at the time of surgery[11]. Since cancer surgeries mandate the removal of entire thyroid tissue even from difficult areas, the RLN is particularly vulnerable at the ligament of Berry[12]. Fortunately, most of the RLN injuries are transient and recover within six months[6].

RLN injury can be classified as follows:

1. Based on duration:

a. Transient

b. Permanent

The time duration for categorizing vocal cord palsy as permanent varies in different series, ranging from 3 to 12 months[13].

2. Based on etiology:

a. Traction

b. Transection

c. Thermal (due to cauterization)

d. Compression

e. Ligation

3. Based on the extent of injury:

a. Type I or segmental

b. Type II or global

Segmental or Type I injury is rapid in onset, more severe and slower to recover. It could be due to traction,cauterization, ligation, or compression around the nerve. Global or Type II injury is more gradual in onset,milder, and more likely to recover rapidly. It is usually due to traction[14].

The vast majority (> 70%) of nerve injuries are traction or stretch related. Majority of traction-related injuries are transient and most recover with time. Dionigiet al.[11]reported that, of all etiologies resulting in RLN paralysis, thermal, clamping, and transection are the most severe resulting in permanent palsy in 28%,50%, and 100% or patients, respectively.

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE NERVE AND BASIS OF IONM

RLN is a mixed motor and sensory nerve; the motor component supplies the intrinsic muscles of the larynx resulting in normal vocal cord movement. The nerve fibers when stimulated release a compound action potential (CAP), which is a sum of impulses of the nerve fibers. The CAP traverses through the nerve resulting in a waveform recordable by placing electrodes at muscle end plates. This is recorded as electromyography (EMG) potentials or compound muscle action potentials (CMAP). Thus, IONM is an EMG recording of CMAP[9].

Intraoperatively, a neural insult results in ischemia of the vasa nervosum when more than 5% of the nerve is stretched, resulting in neuropraxia[9,15]. This progresses to reduction in recruitment of functional nerve fibers resulting in decrease in amplitude[16]. Further insult causes loss of myelin sheaths and axonotmesis resulting in an increase in latency[9]. More than 50% reduction in amplitude and 10% increase in latency is considered significant with respect to loss of nerve function, especially if these combined events occur for 40 s or longer[17]. However, these events are reversible if the offending maneuver is altered (release of traction,etc.).Non-recovery of the amplitude within 20 min, however, portends a high risk for postoperative vocal cord palsy[18].

Physiologically, Wallerian degeneration of the distal segment after the neural insult sets in 48-72 h[19]. Thus,the nerve segment distal to the site of injury continues to generate a response on stimulation intraoperatively[20]. This has implications on monitoring the post dissection response (R2), as described in subsequent sections.

LEARNING CURVE

While understanding neurophysiology is essential for interpretation of the findings of IONM, the experience of the operating team contributes to overcoming problem issues, thus helping identification of impending injuries and aiding crucial intraoperative decisions. This in turn has a bearing on patient counseling with regards the possibilities of change in operative plans. Most authors who have examined the learning curve for application of IONM in thyroidectomies agree that the utility of this tool is proportionate to the experience of the surgeon as well as the anesthetists. It has been estimated that a surgeon would require performing at least 50 consecutive cases with IONM over a 20-month period to gain proficiency in reducing technical errors and improving applicability[21,22]. Once issues related to lack of experience have been overcome, IONM has the ability to complement or even substitute the presence of an experienced guide during surgery[23].

METHODS AND TECHNIQUE

Neurophysiological monitoring can be performed at the level of the brain, spinal cord, cranial nerves, and peripheral nerves. Some of the methods of evaluation include brainstem evoked potentials, triggered EMG,and free-running EMG. In free running EMG, responses are mechanically evoked EMGs measured as burst responses, train activity, and sounds such as the burst of popcorn, a dive bomber, machine gun[24],etc. These responses are obtained even on minimal manipulation such as irrigation of the nerve[25]. Although it aids in monitoring during skull base surgeries[26], it may not be optimal for monitoring the nerve during thyroid surgery where the nerve is in close approximation to the gland. Essentially, nerve integrity monitoring for peripheral nerves, particularly in thyroidectomy, assesses EMG on electrical stimulation with precisely recordable responses. It is performed either intermittently which is most widely used or continuous IONM(CIONM), which is rapidly evolving.

The technique described below is that of open thyroidectomy using a NIM3.0 Response monitoring system(Medtronic Xomed, Jacksonville, Flo, USA).

The setup involves completing a loop of circuits comprising the stimulation side and the recording side,which are connected at an interface. The interface is then connected to a monitor, which displays an auditory and visual response represented by waveforms of amplitude and latency.

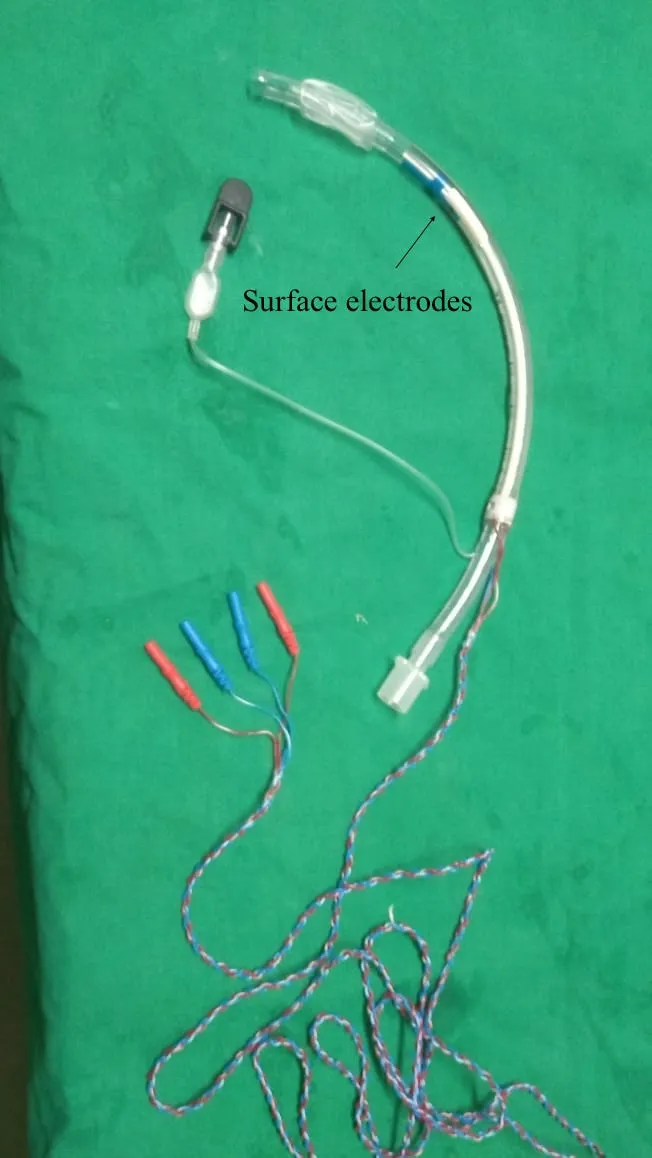

The stimulation circuit comprises a monopolar or bipolar probe which transmits electrical impulses to the nerve and a Stim return electrode (grounding electrode). The recording side comprises the recording electrodes and a ground electrode [Figure 1A and B].

Traditionally, the recording electrodes were inserted onto the vocalis muscle either through the cricothyroid membrane or endoscopically. Other methods of assessment included laryngeal palpation or glottic pressure[27]. This has largely been replaced by mounting the electrodes as surface electrodes on the endotracheal tube to make it less cumbersome[28-31][Figure 2].

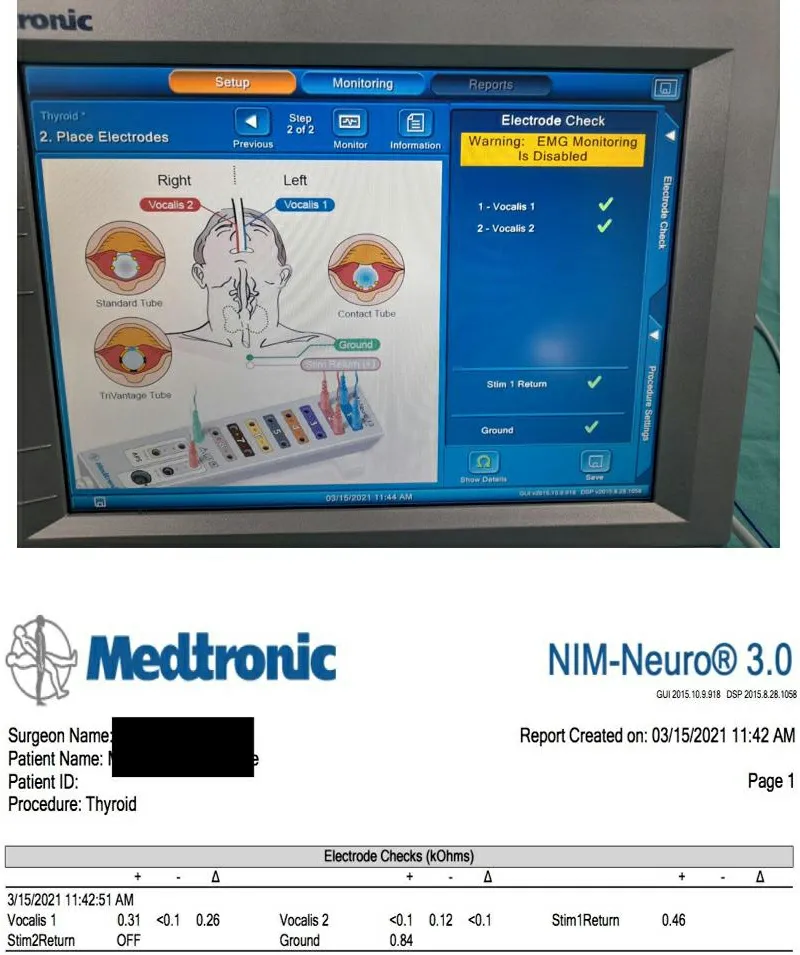

The ground electrodes are inserted on a bony prominence in the vicinity of the operating field, the most suitable location being the sternum or, alternatively, the clavicle[32,33]. These electrodes are connected via the patient interface to the monitor which displays the waveforms. Once all the electrodes are in place, i.e., the surface recording electrodes and the Stim return and ground electrodes, they are verified by a system check on the monitor [Figure 3].

Figure 1. (A) Operating room set up for a thyroidectomy procedure with intraoperative nerve monitoring. (B) Interface between the stimulation side and recording side.

Figure 2. Endotracheal tube with surface electrodes.

Checklist to avoid technical errors during system setup

Tube placement

The tube with mounted electrodes must fit snugly at the level of the vocal cords. Lubrication at the level of the electrodes must be avoided. In addition, neck extension after intubation could misplace the tube and hence tube position must be reconfirmed after the final positioning of the patient[34].

Anesthetic drugs

Avoid muscle relaxants which interfere with CMAP for EMG reading. In addition, the anesthesiologist must ensure that the plane of anesthesia is deep enough to avoid spontaneous vocal cord movement, thus resulting in a disturbing tone due to constant fibrillations of the cords.

Electrical/magnetic interference

Ensure minimal interference from surrounding equipment by acquiring an independent electrical connection for the IONM as well as by using a muting probe on the electrocautery machine[Figure 1A and B].

Figure 3. Electrode check.

The circuit is verified by manually tapping the posterior cricoid to achieve a mechanically stimulated EMG response on the monitor[30].

Electrical settings

The stimulating probe discharges electrical impulses which depolarize axons at the site of stimulation. The stimulation intensity is set at 1 mA and the amplitude threshold is set at 100 µV[31].

Intraoperative steps

Surgery can commence once the system has been set up as described above. After elevation of the subplatysmal flaps, ipsilateral sternomastoid muscle is retracted to expose the carotid sheath. The vagus nerve is either dissected or else mapped on the carotid sheath with the probe with 2 mA amplitude[34]. This is recorded as the pre-dissection vagal (V1) signal. While dissecting the right sided nerve, it is advisable to stimulate the vagus at two points: one above the level of the cricoid and another lower down the neck. A positive signal higher up and a negative signal lower down must alert the surgeon of the possibility of a nonrecurrent laryngeal nerve[35]. The surgery is further continued with retraction of the strap muscles and exposing the ipsilateral thyroid lobe. Dissection is continued with ligation of the superior pole. The first sight of the RLN either at the Beahr’s or Lorre’s triangle is confirmed with the monopolar probe, and the waveform is recorded as the pre-dissection nerve (R1) signal. Once thyroidectomy is completed, the RLN signal is again recorded as the post-dissection nerve (R2) signal. Here, stimulation of the most proximal part of the exposed nerve or the entire visible nerve is necessary to rule out any segmental nerve injury. After completion of hemostasis and approximation of the strap muscles, the vagus is stimulated to achieve Post dissection vagal (V2) signal[35]. The interpretation of the signals is tabulated in Table 1.

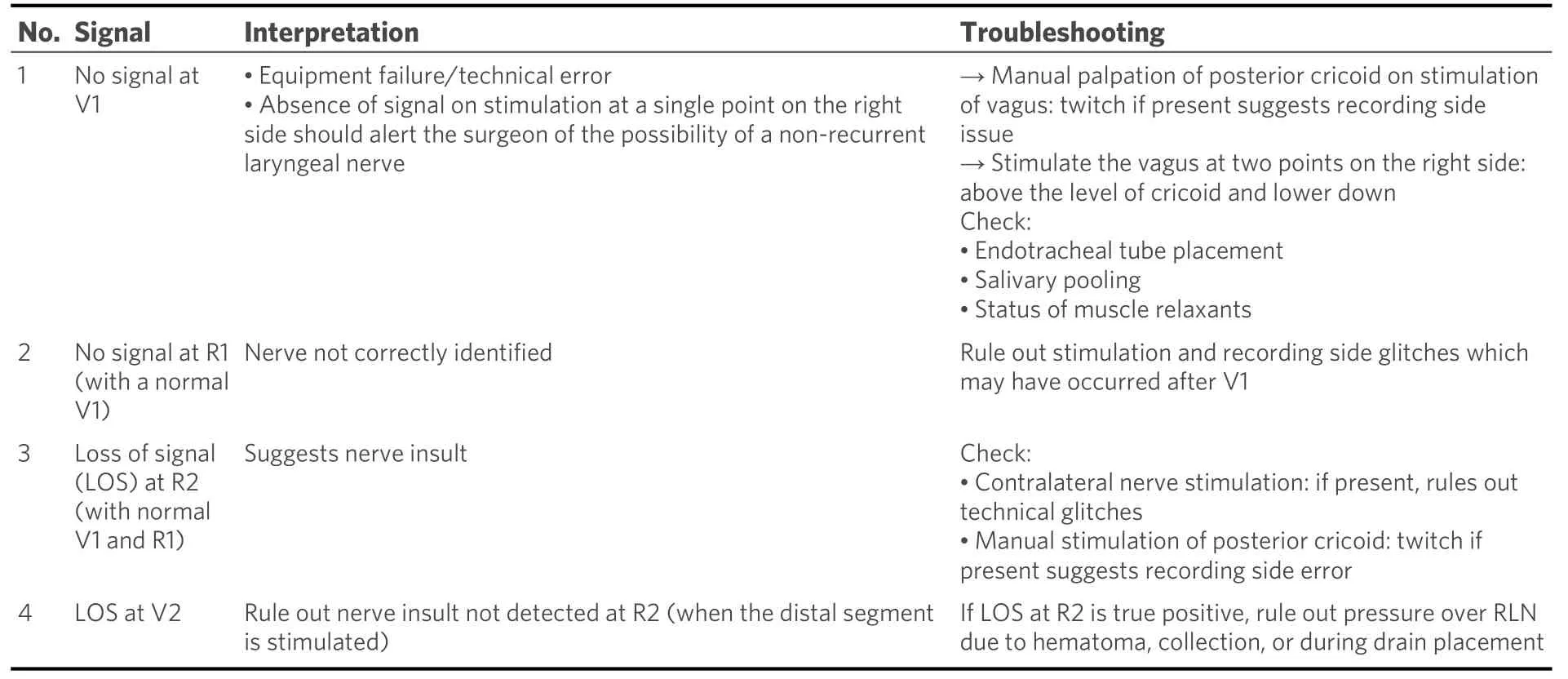

Table 1. Interpretation of signals

An intact signal loop of V1-R1-R2-V2 ensures intactness of the nerve, and the contralateral lobe can be addressed if indicated.

One must be cautious of a normal signal response while eliciting R2 in the presence of nerve injury (false positive signal): this occurs in segmental (Type I) nerve injury when the nerve is stimulated distal to the site of injury. Hence, one must elicit R2 in the entire visible length of the nerve or the proximal most part of the visible nerve to achieve a genuine response.

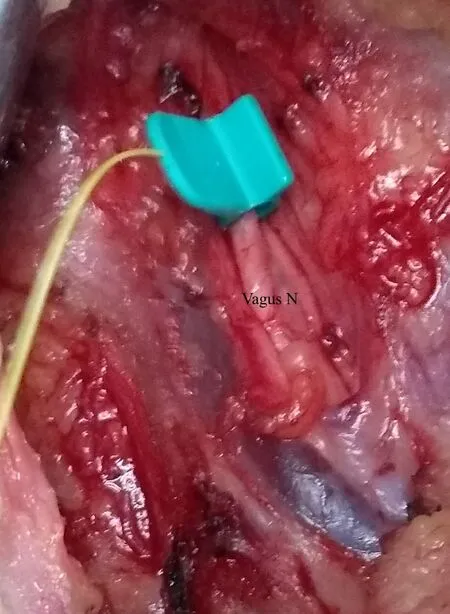

CIONM: After raising the subplatysmal flaps, the carotid sheath is dissected to identify the vagus nerve. The nerve is completely released from the other structures at 360 degrees. An automatic periodic stimulation electrode is inserted hugging the vagus nerve after dissection of the carotid sheath[31][Figure 4]. This electrode delivers continuous low-level stimulation[32]. This electrode replaces the stimulating probe. The rest of the system setup is essentially similar to the intermittent IONM.

Figure 4. Automatic Periodic Stimulation (APS) electrode mounted around the vagus nerve.

READINGS

Normal readings

The cardinal components of readings in an EMG waveform comprise amplitude and latency[36]. An unstimulated muscle does not produce any waveform. There could be non-specific baseline undulations that should be differentiated from evoked waveforms for the human RLN or vagus nerve, which are commonly biphasic or triphasic[37].

The amplitude of a monitoring waveform, as defined in the international guidelines, is the vertical height of the apex of the positive initial waveform deflection to the lowest point in the subsequent opposite polarity phase of the waveform[31].

Latency is taken at the time interval between the point of stimulation and the first peak point of the evoked potential (negative or positive) from the baseline[9,31].

Normative readings of the EMG on the RLN have been determined and can be employed as standards for comparison[38-40]. An optimal IONM signal is a nerve amplitude of ≥ 500 μV at baseline and with a stimulation intensity of 1-2 mA. Sritharanet al.[40]found a mean amplitude of 739.7 mV for the vagus nerve and 891.6 mV for the RLN. An amplitude of > 250 μV is highly predictive of a functioning RLN. This is particularly important while differentiating between preoperative and final postoperative evoked amplitudes at 1 mA. It was found that the final amplitude at the end of dissection/end of surgery (R2) between 247 and 3607 μV is associated with a functional RLN[41].

Figure 5A and B demonstrates readings of the RLN signal pre- and post-dissection suggesting normal functioning nerve.

Figure 5. (A) Pre-dissection right-sided vocalis signal. (B) Post-dissection right-sided vocalis signal.

Latency: In an optimal IONM signal, the expected latency from stimulation to achieving CMAP on the EMG is 3-3.5 ms. Latency, however, differs between the sides as well as the nerves. Potenzaet al.[38]found a median latency of 3.10 ms for the right RLN and 4.25 ms for the left RLN. The right vagus demonstrated a median latency of 6.47 ms and the left vagus had a median latency of 7.42 ms. In another study,Sritharanet al.[40]found the mean latency of the left vagus to be 8.14 ms compared to a mean right vagal latency of 5.47 ms. In the same series, the mean left RLN latency was 4.19 ms, while the mean right RLN latency was 3.73 ms.

Abnormal readings and signs of impending or actual nerve injury

An EMG is considered to be abnormal if either the amplitude or latency is affected; these changes may be isolated or combined. The latter, i.e., combined events, are seen to be more predictive of function loss[38].This is because isolated abnormal readings of variable, amplitude or latency, could arise from technical glitches. Combined events could be mild or severe. Mild combined events are those where the amplitude decreases from > 50% to 70% with a concordant latency increase of 5%-10%. Severe combined events (sCEs)are those with reduction in the amplitude of > 70% with a latency increase of > 10%. Phelanet al.[17]reported six cases that developed a temporary VCP, and, of those, 83% had developed intraoperative sCEs. Moreover,the average number of sCEs for group was 29. On the other hand, of the patients with a normal postoperative vocal cord examination, only 20% developed sCEs during surgery and, importantly, the average number of sCEs for this group was 3.5[17].

When such combined events happen, it is crucial to release the nerve immediately by relaxing traction (the most common cause) and to wait until the nerve amplitude has regained ≥ 50% of its baseline. If these CEs recur repeatedly, the surgeon may consider changing their surgical strategy, e.g., a lateral approach as opposed to a midline approach. If the basic cause is not removable and the CE persist for 40 s or longer and if the initial injury was severe, the CEs may progress to “loss of signal” (LOS)[17,41].LOS is defined as either complete loss of amplitude or decrease of the nerve amplitude to 100 µV after suprathreshold stimulation (1-2 mA), paying careful attention to troubleshooting algorithms[31].

Not all cases with LOS will have permanent RLN palsy. The literature suggests that recovery of amplitude to 50% of baseline amplitude always indicated normal early postoperative vocal fold function[40]. However, LOS is a grave finding, and, in this series, only 17% of those with LOS intraoperatively exhibited recovery[17]. LOS developing acutely was more likely to develop into nerve palsy as opposed to a gradually occurring LOS[42].LOS, if transient, generally recovers within 20 min of occurrence[18,21].

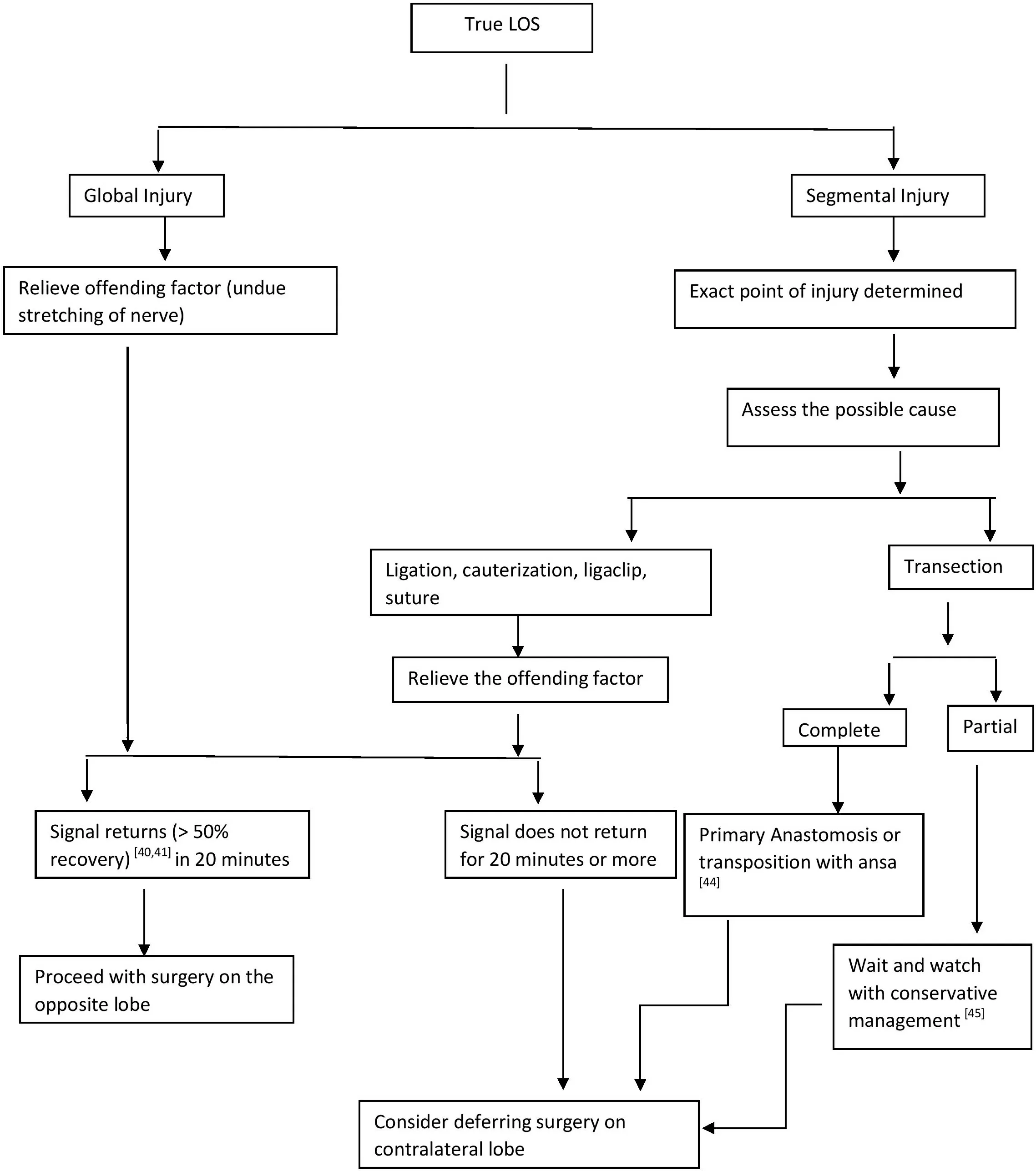

MANAGEMENT DECISIONS AFTER TRUE LOS

True LOS could suggest either Type I (segmental Injury) or Type II (global Injury).

Segmental injury

There is a positive EMG signal at laryngeal entry point but negative signal at the most proximal point of the exposed RLN[43]. The point of injury can be picked on stimulating the nerve in its entirety from the distal most point of entry proximally. The point at which the signal stops is the point of injury.

Global injury

When there is no EMG signal in the entirety of the visible portion of the nerve, it is Type II injury.However, the signal is elicited on the opposite vagal stimulation. Figure 6 gives an algorithm on the management decision in case of true LOS.

Figure 6. Algorithm for intraoperative decision-making in true LOS.

OUTCOMES OF USE OF IONM

Performance of the IONM

Various series have reported a high negative predictive value (NPV) of the IONM upwards of 95%[46-48],making it suitable to predict that the nerve is intact. Nonetheless, IONM has a learning curve, and the operating team may encounter hurdles until a normal signal is achieved. This gives a high false LOS reducing the positive predictive value of 12%-88%. There has been a prospective randomized controlled trial comparing conventional thyroidectomy with IONMvs. no IONM. Forty-one nerves at risk in patients with benign as well as malignant disease were operated on by two experienced surgeons. The findings demonstrate no RLN injuries in both arms, although the operative time for nerve identification was significantly lower in the IONM group notwithstanding the fact that total surgery time was not significantly different. Even in experienced hands, there was one false LOS (1/41, 2.4%)[49].

Thus, from available evidence, IONM can prove beyond doubt that the nerve is normally functioning in the presence of a normal signal and one can proceed with surgery on the contralateral side. However, decision making in the case of LOS requires expert opinion in high-volume centers to negate false LOS.

Outcomes in surgeries of thyroid cancer

There is growing consensus among thyroid surgeons over deferring contralateral surgery in the event of LOS on ipsilateral side with the International Neuromonitoring Study Group endorsing this viewpoint[20].While this would be easier in surgery of benign disease, deferring surgery of the contralateral side in thyroid cancers is a contentious issue and much debated. Needless to mention, apart from a second surgical insult,there is a question of oncological safety. There is some evidence of favorable outcomes from high-volume centers, albeit with limited numbers in support of staged surgery. The authors of one study suggested no deterioration in oncologic outcomes by deferring contralateral surgery in 35 patients of locally advanced thyroid cancers, both differentiated and medullary cancers[33,50].

However, the authors also suggested a balanced individualized decision based on surgical fitness for second surgery, appropriate counseling of the patients, and the nature of the disease before making a decision.

Deferring surgery due to LOS on ipsilateral side

In high-volume centers, where the learning curve is surpassed and probability of false LOS is minimized,there is evidence to suggest deferring surgery on the contralateral side prevents incidence of bilateral vocal cord palsy as opposed to those performing contralateral surgery from 17%-28.6% to 0%[31,51,52].

SPECIAL CIRCUMSTANCES

The utility of IONM is being evaluated and appreciated in the following situations.

Mapping of the RLN

In difficult scenarios such as redo surgeries and infiltrative thyroid cancers, the RLN may be difficult to identify. In such cases, increasing the stimulation intensity to up to 2 mA helps to localize the nerve. After identification, further stimulation can be done by reducing the intensity to 1 mA[39].

Invasive thyroid cancers

The American Head Neck Society, in a consensus statement, has recommended the use of IONM for all cases of invasive thyroid cancers[47]. In such cases, with a preoperative mobile vocal cord, if intraoperative signal at R1 is present proximal to the infiltrative tumor, all attempts should be made at nerve preservation[48]. Similarly, in the presence of preoperative vocal cord dysfunction, more than 30% patients demonstrate an EMG response when stimulated proximally. Preservation of such nerves results in maintenance of vocalis muscle tone, thus avoiding atrophy and resultant aspiration due to phonatory gap.Additionally, dissection of the RLN from the tumor while still preserving its integrity has been found to be easier if IONM is employed.

Day care thyroidectomy

IONM, with its high negative predictive value (> 95%), largely rules out postoperative vocal cord dysfunction in the presence of normal signal. The confirmation of nerve integrity at the end of the surgical procedure using IONM can help in making the decision of discharging a patient on the day of surgery provided all other criteria are fulfilled[53].

Paediatric thyroidectomy

In cases of patients less than 18 years with thyroid neoplasms, IONM has been found to be useful;continuous monitoring is recommended over intermittent monitoring for prevention of complications[54].Technical modifications to the equipment have been made to facilitate the use of IONM in children.

Challenging anatomic variations

Anatomical variations of the RLN are not infrequent, although they cannot be preempted.

(1) Extra laryngeal motor branches of the RLN are not uncommon. The RLN may branch more than 5 mm away from its entry into the larynx. Failure to recognize such branching may result in palsy despite an intact appearing nerve[55]. IONM helps in preventing this by identification of the motor branches, especially as these smaller branches may be mistaken for branches of the inferior thyroid artery and therefore may be ligated or cauterized.

(2) Non-RLN: As is well known, a non-recurrent laryngeal nerve is encountered in 0.6%-1% of all thyroidectomies, and it is almost exclusively seen on the right side[56]. Since there is no cost-effective method of identifying it preoperatively, it is best to stay aware of the entity and identify it. IONM is an effective tool in confirming a non-recurrent nerve if it exists. This is done by confirming an EMG signal from the laryngeal muscles on proximal stimulation of the vagus nerve at the level of the superior border of the thyroid cartilage in the absence of such a response distally at the level of the fourth trachea ring.

RECENT ADVANCES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

CIONM

CIONM, with real time monitoring, alerts the surgeon to an impending injury before actual insult to the nerve. It removes the risk to the nerve due to the temporal gap (interval between stimulations) and spatial gap (distance between the site of stimulation and the site of injury) that can happen in intermittent IONM(IIONM)[57]. Thus, the probability of permanent vocal cord palsy with CIONM is less than that of IIONM[46]. The lower risk of injury to the RLN translates into higher conversion to total thyroidectomy with the use of CIONM, as was concluded by Schneideret al.[46]in their study of 1314 nerves at risk. The caveat is the need for extra dissection not just of the carotid sheath but also 360-degree release of the vagus for mounting and accommodating the stimulating electrode. It has been nonetheless found to be safe with respect to voice outcomes even in professional voice users[58]. Additionally, continuous albeit low-voltage stimulation of the vagus was feared to potentially increase the risk of heart blocks especially in a patient with heart disease. This has been negated by available data which suggest safety even in patients with heart blocks[59].

Monitoring of the external branch of superior laryngeal nerve

The International Neuromonitoring Study Group has defined the role of monitoring of External Branch of Laryngeal Nerve (EBSLN)[60]. Several workers have demonstrated the feasibility and efficacy of IONM in mapping the EBSLN[61,62]. The identification of the EBSLN has been shown to be consistently better with IONM as compared to visual identification[63]. There may, however, be technical and instrumental modifications required for the proper recording of the EBSLN readings and these are still evolving.

Use of IONM in remote access thyroidectomy

IONM has been demonstrated to be useful in endoscopic and robotic thyroidectomies via all approaches[64,65]. The voice outcomes are similar to non-IONM procedures though the recovery to normal speech has been seen to be more rapid with the use of IONM. CIONM is more easily integrated in such surgeries. However, there may be difficulties involved[66], and the rate of artifacts and false positives may be higher than in open surgeries.

CONCLUSION

IONM is a useful adjunct in thyroid surgeries, particularly in difficult thyroid cancers, as has been highlighted in the literature[67,68]. It helps not only to identify but also to preserve and prognosticate nerve injury with advances in precision recording. The learning curve of this technique is not unsurmountable.Having achieved that, incorporation of the IONM has a bearing on critical intraoperative decision-making with regards to patient safety. Continuing innovation in IONM design as well as the fast-emerging role of CIONM will further enhance the efficacy and applicability of this tool even in remote access thyroidectomies.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to conception and design of study, data analysis and interpretation:Priya SR, Dandekar M

Performed data acquisition, technical and material support: Garg S, Priya SR, Dandekar M

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2021.

Journal of Cancer Metastasis and Treatment2021年12期

Journal of Cancer Metastasis and Treatment2021年12期

- Journal of Cancer Metastasis and Treatment的其它文章

- Progress in the treatment of NK-cell lymphoma/leukemia

- Novel standards and emerging therapies for systemically treatment-naïve clear cell renal cell carcinoma - a rapidly changing landscape

- The contemporary role of metastasectomy in the management of metastatic RCC

- Cancer-directed surgery in malignant pleural mesothelioma: extrapleural pneumonectomy and pleurectomy/decortication

- AUTHOR INSTRUCTIONS