Progress in the treatment of NK-cell lymphoma/leukemia

Ayumi Fujimoto, Ritsuro Suzuki

Department of Hematology, Shimane University Hospital, Izumo, Shimane 693-8501, Japan.

Abstract Natural killer (NK)/T cell lymphoma includes two major subtypes of disease, specifically extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal type (ENKL) and aggressive NK cell leukemia (ANKL). Both are strongly associated with Epstein-Barr virus and are prevalent in East Asia and Latin America. Except for that of limited-stage ENKL, the prognosis of both diseases was poor in the previous decade. The advent of non-anthracycline-based chemoradiotherapy has contributed to an improvement in ENKL prognosis, but there is still room for further treatment progress. Recently,the high efficacy of PD-1 antibody was reported in relapsed or refractory ENKL patients. This was later supported by the finding that PD-L1/PD-L2 genetic alterations are frequently observed in ENKL and ANKL patients. Due to the rarity of the disease, a standard treatment for ANKL remains to be established. Currently, allogeneic stem cell transplantation is the only curative treatment, and this is even applicable to chemo-resistant ANKL patients. In this review, we focus on recent treatment approaches for NK/T cell lymphomas including novel agents.

Keywords: Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type, aggressive NK-cell leukemia, Epstein-Barr virus,hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, L-asparaginase

INTRODUCTION

Natural killer (NK) cell neoplasms are rare hematological malignancies, with two major subtypes of extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal type (ENKL) and aggressive NK-cell leukemia (ANKL)[1]. Both ENKL and ANKL are strongly associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)[1]. The geographic distribution of ENKL is distinctive, with a particularly high prevalence in East Asia and South America. ENKL corresponds to approximately 2%-11% of cases among all lymphoma subtypes in East Asian countries, whereas the prevalence is less than 1% in the United States and Europe[2-4]. Although the distribution and incidence of ANKL are unclear due to its rarity, the prevalence is approximately one-sixth that of ENKL, accounting for fewer than 1% of cases among all malignant lymphomas[5]. ENKL is distinct from other lymphomas based on its unique characteristics, comprising the dominant involvement of the nasal cavity and nasopharynx.The majority of ENKL cases are limited to a location around the nose or upper aerodigestive tract,presenting with typical symptoms of nasal obstruction, epistaxis, or rhinorrhea. In contrast, ANKL is prevalent in the peripheral blood, bone marrow, liver, and spleen. Most patients suffer general symptoms,such as fever, general malaise, and loss of appetite. Clinical courses of advanced-stage ENKL and ANKL are very aggressive, often leading to disseminated intravascular coagulation and multiorgan dysfunction, thus resulting in a poor prognosis over the past decade. Recently, with an increasing understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of NK cell neoplasms, novel treatment strategies including targeted agents are expected to improve survival. In this review, we highlight recent clinical findings for ENKL and ANKL and discuss future prospects.

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF NK/T CELL LYMPHOMA/LEUKEMIA

The annual incidence of ENKL varies by ethnicity and geographically from 0.06 in the United States to 0.25 in Hong Kong per 100,000 population[3]. ENKL predominantly occurs in middle-aged individuals with a median age of 52-58 years[5-8]. The incidence is 1.5 times higher in males. Because ENKL commonly develops in extranodal sites and approximately 10% of ENKL cases are derived from γδ or cytotoxic T cells[9], the disease is termed extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma in the World Health Organization (WHO)classification. The nasal or paranasal cavities and the upper aerodigestive tract are involved in more than 80% of ENKL cases, with approximately 70% of these being in a limited stage at diagnosis[5]. The patient’s initial complaints are generally focal symptoms such as nasal obstruction, epistaxis, and rhinorrhea. In contrast, the remaining cases develop in extra-nasal sites such as the skin, gastrointestinal tract, lung, or other uncommon organs[5,7]. Approximately 60% of cases with an extra-nasal origin are at an advanced stage at diagnosis. Because ENKL develops predominantly in extranodal sites, stage III cases are rare, occurring in fewer than 5% of all cases. Therefore, most cases in advanced stage are diagnosed as stage IV. These cases follow an aggressive clinical course with hemophagocytic syndrome and/or disseminated intravascular coagulation.

ANKL is a rare leukemic form of NK cell neoplasms, which has been reported mainly in East Asian countries such as Japan, China, or South Korea. The incidence is 2-3 times higher in males. ANKL progresses very rapidly, and its very aggressive clinical course is reflected by its name, aggressive NK-cell leukemia[10]. The median overall survival (OS) of ANKL is only a few months after diagnosis, which is the worst prognosis among all lymphoma subtypes[11]. Interestingly, however, a subset of ANKL shows a subacute clinical course. These subacute-type patients demonstrate female predominance and better prognosis with a median OS of more than six months. The median age for ANKL development is 40-42 years old, which is more than 10 years younger than that of ENKL, but it is also distributed in an elderly population, older than 70 years of age[5,12]. Although most ANKL cases developde novo, there are some cases that originate from EBV-associated T/NK lymphoproliferative disease, including chronic active EBV infection, which generally develops in a younger population[13]. Unlike ENKL, the clinical symptoms of ANKL are non-specific, including fever, general malaise, and loss of appetite. Most patients have hepatomegaly and splenomegaly; thus, increased levels of lactate dehydrogenase and liver enzymes are commonly observed. Therefore, the accurate diagnosis of ANKL is often difficult, and a postmortem diagnosis is sometimes made after an inaccurate diagnosis of acute hepatitis. Complete blood counts show pancytopenia, and the morphology of leukemic cells varies widely, from normal large granular lymphocyte to lymphoid cells with atypical nuclei and a prominent nucleolus. Occasionally, the percentage of tumor cells in the bone marrow and peripheral blood is much lower than that in acute myeloid or lymphoblastic leukemia, with median percentages of 22% and 8%, respectively[12]. Therefore, it is important to consider ANKL as a differential diagnosis particularly in cases with fever of unknown origin, hepatosplenomegaly, or liver dysfunction.

The detection of EBV is required to make a diagnosis of ENKL based on the current WHO classification[1],whereas this is not mandated for ANKL since approximately 10%-15% of ANKL cases are negative for EBV[12,14]. The differences in clinical course and prognosis between ANKL patients with and without EBV infection are also controversial[12,14,15].

PROGNOSIS AND PROGNOSTIC MODELS

Several recent reports show that the prognosis of limited-stage ENKL patients has been improved through the introduction of several effective treatments in the past decade. However, the prognosis of advancedstage ENKL patients is still unsatisfactory[7,8,16]. The patients with limited-stage ENKL have a significantly better prognosis than those with advanced-stage ENKL[7]. In the largest retrospective study of 358 ENKL patients, the five-year OS and progression-free survival (PFS) of limited-stage ENKL patients were 68% and 56%, respectively. In addition, the prognosis was significantly better for the limited-stage ENKL patients treated between 2010 and 2013 than for those treated between 2000 and 2009 (five-year OS of 79% and 63%,respectively)[7]. One of the reasons for this survival improvement is that the rate of limited-stage patients treated with effective chemoradiotherapies has increased[16]. More recently, the prognosis of limited-stage ENKL, when achieving event-free survival at 24 months after diagnosis, was demonstrated to be almost equivalent to that of the age- and sex-matched general population[17]. In contrast, the prognosis of advancedstage ENKL is still poor with five-year OS and PFS values of 24% and 16%, respectively[7]. Although the introduction of L-asparaginase (L-asp)-containing chemotherapy has improved the OS, significant improvements in clinical practice have not been obtained yet[16].

The most popular prognostic model for ENKL is the prognostic index of NK lymphoma (PINK)[18]. This model was developed to predict the prognosis for treatment-naïve ENKL patients who received nonanthracycline-based chemotherapies with curative intent. Based on four prognostic factors, including age older than 60 years, stage III or IV, distant lymph-node involvement, and non-nasal type disease, patients are stratified into low risk (0), intermediate risk (1), and high risk (2-4) categories, with estimated three-year OS of 81%, 62%, and 25%, respectively. PINK-E, a prognostic model including EBV-DNA data on PINK,also links risk factors and OS. The international prognostic index and NK/T cell lymphoma prognostic index, previously developed prognostic models, were based on patient data of the anthracycline era, and these do not provide an accurate prognosis for patients receiving recent non-anthracycline-based chemotherapies[7,19].

The prognosis of ENKL differs by the site of origin, specifically nasal or extranasal. The prognosis of patients with an extranasal origin is significantly worse than that of patients with a nasal origin based on several studies[6,8]. The largest prospective cohort study of ENKL patients, from the International T cell Project, showed an OS at five years of 54% in patients with nasal origin and 34% in those with extranasal origin (log-rankP= 0.019)[8]. However, the impact of the site of disease origin, nasal or extranasal, on OS is controversial. Because the percentage of advanced stage disease is generally higher in patients with extranasal origin than in those with nasal origin, the disease stage could be a confounding factor when evaluating the prognosis by the site of disease origin. In fact, another study reported that prognosis does not significantly differ between the two groups in subgroup analyses by disease stage[20].

There are no prognostic models for ANKL. In general, the prognosis of this disease is extremely poor, with a median OS of 2-3 months[5,11,12], except for that of the subacute-type ANKL[21]. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation is the only curative treatment and could be the most important factor for survival. Patients with subacute ANKL have symptoms of infectious mononucleosis for more than 90 days prior to the fulminant onset, and the prognosis is significantly better than that of typical ANKL, with a median OS of 214 days[21]. ANKL originating from EBV-associated NK/T cell lymphoproliferative diseases such as chronic active EBV infection has been reported[13], but its clinical course and prognosis are not well known.

TREATMENT OF NK-CELL LYMPHOMA

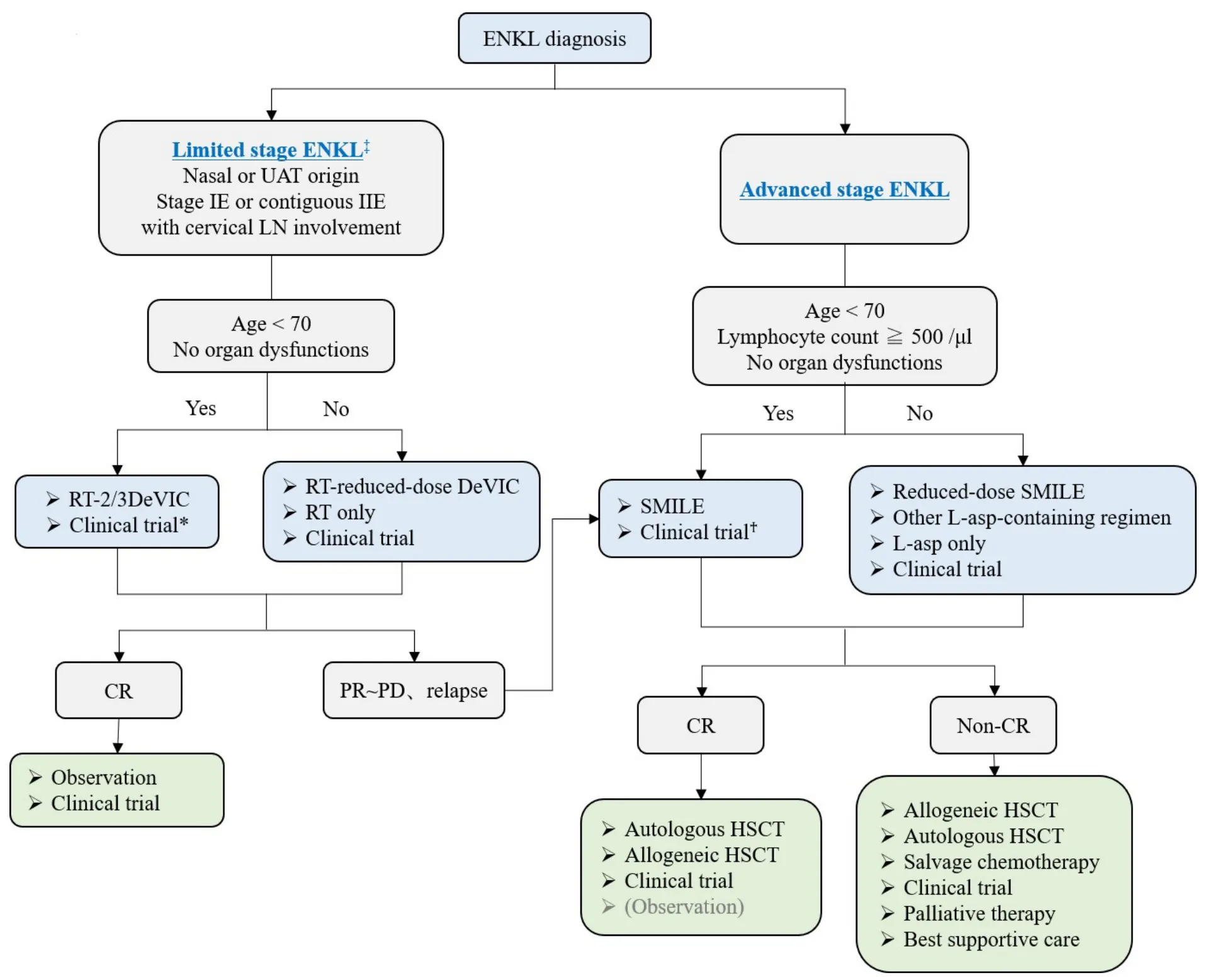

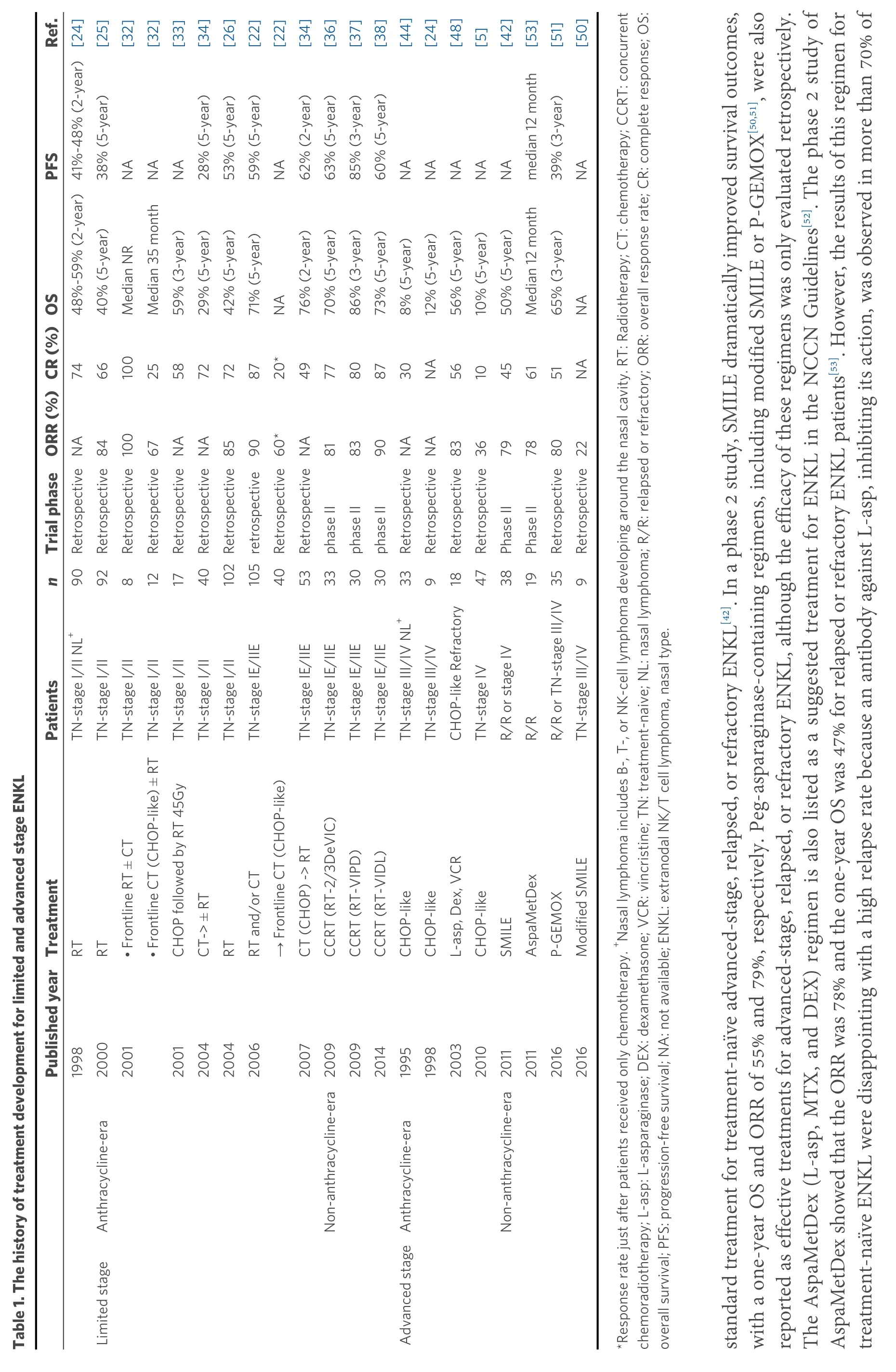

The recommended algorithm of treatments for ENKL patients is shown in Figure 1. The scheme is divided based on the extent of disease (limitedvs.advanced). The history of treatment development is further shown in Table 1.

Figure 1. Treatment flowchart of ENKL patients. *CCRT-VIPD and CCRT-VIDL regimens are included. AspaMetDex regimen is included only in relapsed or refractory ENKL patients. ‡The definition of limited stage in this flowchart is a little different from that in the conventional Lugano/Ann Arbor classification. UAT: Upper aerodigestive tract; LN: lymph node; RT: radiotherapy; DeVIC:dexamethasone, etoposide, ifosfamide, carboplatin; CR: complete response; PR: partial response; PD: progressive disease; SMILE:steroid, methotrexate, ifosfamide, L-asparaginase, etoposide; L-asp: L-asparaginase; HSCT: hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Limited-stage ENKL

For limited-stage ENKL, concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) is recommended as a first-line therapy.Radiotherapy (RT) has been used as an effective treatment for limited-stage ENKL since the 1980s[22].Although RT-containing treatment provides significantly better outcomes for limited-stage ENKL[23], RT alone frequently induces local or systemic treatment failure in more than 50% of patients[24-26]. Several studies have shown that the recommended dose of RT that is necessary for local control of limited-stage ENKL is 50 Gy or more[23,27,28]. A combination of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) and RT is an established treatment for localized non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and it is also used to treat ENKL patients[29]. However, because normal and abnormal NK cells express multidrug resistant(MDR)-associated P-glycoprotein[30,31], anthracycline-containing regimens such as CHOP are not satisfactory for treating ENKL patients, with a five-year OS of less than 50%, even combined with RT[6,24,32,33].In addition, chemotherapy followed by RT was shown to yield a worse response rate than RT followed by chemotherapy for limited-stage ENKL in a few studies[22,34,35]. Based on these experiences, several CCRT regimens have been developed as novel anti-MDR treatments for limited-stage ENKL patients since the early 2000s[36-38]. These regimens consist of non-MDR-associated anti-cancer agents, such as platinum derivatives, and ifosfamide (IFM), L-asp which hasin vitrosensitivity against an NK cell tumor cell line[39],or etoposide (ETP) which is known to be effective against EBV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome[40,41].One of the most popular CCRT regimens is RT-2/3DeVIC (dexamethasone, ETP, IFM, and carboplatin)[36],which includes concurrent RT of 50-50.4 Gy in 25-28 fractions with three cycles of a two-third dose of DeVIC. The efficacy of RT-2/3DeVIC therapy for newly diagnosed stage IE or contiguous IIE ENKL patients is better with a two-year OS of 78% and an overall response rate (ORR) of 81%, relative to the historical data. The adverse events (AEs) of RT-2/3DeVIC are acceptable. There have been no treatmentrelated deaths and only neutropenia was reported as a Grade 4 AE, developing in more than 20% of the patients. Other CCRT regimens used in Korea, such as CCRT-VIPD [ETP, IFM, cisplatin (CDDP), and dexamethasone (DEX)] and CCRT-VIDL (ETP, IFM, DEX, and L-asp)[37,38], have common characteristics such as RT with a median of 40 Gy conducted with weekly CDDP monotherapy, and then combination chemotherapy is conducted after RT completion. VIPD is given every three weeks for three cycles after 3-5 weeks from the time of CCRT completion[37]. VIDL is similar to VIPD, but L-asp is used instead of CDDP every other day from Day 8 to Day 20, as in the SMILE regimen[38,42]. VIDL is given every three weeks for two cycles after 3-4 weeks from the time of CCRT completion[38]. Compared to the RT-2/3DeVIC regimen,these regimens include a lower dose of RT and take a longer time to complete the treatment, but both results are good and comparable to those of RT-2/3DeVIC. VIDL shows less hematologic toxicity than VIPD, but there are no trials comparing these regimens. RT-2/3DeVIC is the most commonly used regimen in Japan. Recently, its durable response was reported with a five-year OS of 70%[7]. Although there are several sequential chemoradiotherapies, no significant difference in OS has been observed compared to that with CCRT[43], and no studies comparing an efficacy of each regimen have been reported.

Advanced-stage ENKL

For advanced stage ENKL, SMILE [steroid (DEX), methotrexate (MTX), IFM, L-asp, and ETP]chemotherapy is the most recommended regimen as a first-line therapy. Compared to that with peripheral T-cell lymphoma, because of the MDR-associated P-glycoprotein described previously herein, CHOP is much less effective for advanced-stage ENKL patients, with a five-year OS of only 8%-12%[5,24,44]. The durable efficacy of L-asp monotherapy for CHOP-resistant ENKL patients was reported in several cases[45,46], and Lasp-containing combination chemotherapy has been developed[47-49]. The SMILE regimen, which is a nonanthracycline-containing and non-MDR-associated agent-containing combination chemotherapy, is the patients after the first cycle and eventually observed in all patients[54]. Therefore, AspaMetDex should only be used in a relapsed or refractory setting of the disease. Only a prospective clinical trial comparing the efficacy of DDGP (DEX, CDDP, gemcitabine, and peg-asparaginase) and SMILE has been reported from China, but the results cannot be evaluated owing to the poor study design[55]. The authors included a larger proportion of stage III ENKL patients than that found in the historical data (usually less than 20% of advanced-stage ENKL), and the methods and patient selection criteria described were different from the registered data on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01501149). Therefore, we conclude that the recommended standard treatment for advanced-stage ENKL is still the SMILE regimen[42].

Ref.[25][32][32][33][34][26][22][22][34][36][37][38][44][24][48][5][42][53][51][50]PFS 38% (5-year)NA NA NA 28% (5-year)53% (5-year)59% (5-year)NA 62% (2-year)63% (5-year)85% (3-year)60% (5-year)NA NA NA NA NA median 12 month 39% (3-year)NA Trial phaseORR (%)CR (%)OS 48%-59% (2-year)41%-48% (2-year)[24]40% (5-year)Median NR Median 35 month 59% (3-year)29% (5-year)42% (5-year)71% (5-year)NA 76% (2-year)70% (5-year)86% (3-year)73% (5-year)8% (5-year)12% (5-year)56% (5-year)10% (5-year)50% (5-year)Median 12 month 65% (3-year)NA 74 66 100 25 58 72 72 87 20*49 77 80 87 30 NA 56 10 45 61 51 NA RetrospectiveNA Retrospective84 Retrospective100 Retrospective67 RetrospectiveNA RetrospectiveNA 85 90 Retrospective60*RetrospectiveNA 81 83 90 79 78 105retrospective phase II phase II phase II RetrospectiveNA RetrospectiveNA Retrospective83 Retrospective36 Phase II Phase II Retrospective80 Retrospective22 n 92 812 TN-stage I/II NL+90 17 40 102Retrospective 40 53 33 30 30 918 47 38 19 35 9 Patients TN-stage I/II TN-stage I/II TN-stage I/II TN-stage I/II TN-stage I/II TN-stage I/II TN-stage IE/IIE TN-stage IE/IIE TN-stage IE/IIE TN-stage IE/IIE TN-stage IE/IIE TN-stage III/IV NL+33 TN-stage III/IV CHOP-like Refractory TN-stage IV R/R or stage IV R/R R/R or TN-stage III/IV TN-stage III/IV Table 1. The history of treatment development for limited and advanced stage ENKL Treatment RT RT • Frontline CT (CHOP-like) ± RT CHOP followed by RT 45Gy CT-> ± RT RT RT and/or CT→ Frontline CT (CHOP-like)CT (CHOP) -> RT CCRT (RT-2/3DeVIC)CCRT (RT-VIPD)CCRT (RT-VIDL)CHOP-like CHOP-like L-asp, Dex, VCR CHOP-like SMILE AspaMetDex P-GEMOX Modified SMILE Published year 1998 2000 2001• Frontline RT ± CT 2001 2004 2004 2006 2007 2009 2009 2014 1995 1998 2003 2010 2011 2011 2016 2016 Anthracycline-era Non-anthracycline-era Anthracycline-era Non-anthracycline-era Limited stage Advanced stage*Response rate just after patients received only chemotherapy. +Nasal lymphoma includes B-, T-, or NK-cell lymphoma developing around the nasal cavity. RT: Radiotherapy; CT: chemotherapy; CCRT: concurrent chemoradiotherapy; L-asp: L-asparaginase; DEX: dexamethasone; VCR: vincristine; TN: treatment-naive; NL: nasal lymphoma; R/R: relapsed or refractory; ORR: overall response rate; CR: complete response; OS:overall survival; PFS: progression-free survival; NA: not available; ENKL: extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal type.standard treatment for treatment-naïve advanced-stage, relapsed, or refractory ENKL[42]. In a phase 2 study, SMILE dramatically improved survival outcomes,with a one-year OS and ORR of 55% and 79%, respectively. Peg-asparaginase-containing regimens, including modified SMILE or P-GEMOX[50,51], were also reported as effective treatments for advanced-stage, relapsed, or refractory ENKL, although the efficacy of these regimens was only evaluated retrospectively.The AspaMetDex (L-asp, MTX, and DEX) regimen is also listed as a suggested treatment for ENKL in the NCCN Guidelines[52]. The phase 2 study of AspaMetDex showed that the ORR was 78% and the one-year OS was 47% for relapsed or refractory ENKL patients[53]. However, the results of this regimen for treatment-naïve ENKL were disappointing with a high relapse rate because an antibody against L-asp, inhibiting its action, was observed in more than 70% of

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for ENKL

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is recommended for relapsed or refractory limited-stage ENKL, in which a complete response (CR) is not achieved after the first-line treatment, as well as for advanced-stage ENKL. The advantage of upfront HSCT has not been established in limited-stage ENKL patients or ENKL patients with favorable risk factors who achieved first CR after induction therapy[56]. In contrast, the results of a SMILE phase 2 study suggest that the OS of patients with advanced-stage, relapsed,or refractory ENKL is better in the HSCT group than in the non-HSCT group[42]. Therefore, HSCT remains the mainstay for advanced-stage ENKL in the first CR or partial response (PR). Although autologous HSCT and allogeneic HSCT have not been compared, generally, autologous HSCT is recommended for relapsed limited-stage ENKL patients with chemo-sensitivity or advanced-stage ENKL patients who achieve first CR or PR after L-asp-containing chemotherapy, and allogeneic HSCT is recommended for the remaining patients[57]. Recently, the efficacy of four cycles of VIDL followed by up-front autologous HSCT in newly diagnosed advanced-stage ENKL patients was reported in Korea[58]. Seventeen of 24 patients prospectively included in this phase 2 study, who achieved CR or PR after four cycles of VIDL, finally proceeded with upfront autologous HSCT. The median duration of the response was 15.2 months. However, nine patients(53%) relapsed after HSCT and four (24%) of the nine relapsed in the central nervous system (CNS).Therefore, we have to pay attention to CNS relapse in ENKL patients who received HSCT. Further, these results suggest that advanced-stage ENKL patients, especially those with risk factors for CNS involvement,should be treated with intermediate-dose MTX-containing chemotherapy, including SMILE, and upfront HSCT[59]. The durable efficacy of allogeneic HSCT for ENKL was reported from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) with a three-year OS of 34% and no relapse after two years from HSCT treatment[60].

ANKL

A standard treatment for ANKL has not been established, and there are no prospective clinical trials for ANKL patients due to its rarity. The anthracycline-containing regimen is not effective for ANKL, with a median OS of 2-3 months[5]. SMILE therapy is recommended as a first-line treatment for ANKL, as for advanced-stage ENKL, although the reported evidence is limited. In a small-scale retrospective study, the ORR of SMILE therapy in 13 patients with ANKL was 38%[61]. Since ANKL progresses rapidly, most patients have B symptoms, liver dysfunction, and a poor general condition at diagnosis[5,12]. The dose of anti-cancer agents in SMILE can be reduced for such comorbid patients. Another alternative is an L-asp monotherapy followed by SMILE therapy after an improvement in organ function or the general condition. One case report showed the successful treatment with L-asp monotherapy as a first-line therapy for ANKL with severe liver dysfunction at diagnosis[62]. In that case, SMILE was supplemented after the improvement of liver function with L-asp monotherapy.

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for ANKL

Most ANKL patients who do not receive allogeneic HSCT, even if they achieve CR after induction chemotherapy, progress to relapse disease and eventually die[5,11,12]. Therefore, allogeneic HSCT is recommended for all ANKL patients who achieve a response and are eligible for this procedure. The effectiveness of allogeneic HSCT for ANKL was first reported in 1996[63]. Small-scale retrospective studies showing durable response and long-term survival for ANKL patients who received allogeneic HSCT have been reported since then[21,64,65]. A retrospective study of 21 ANKL patients who underwent allogeneic HSCT reported from CIBMTR showed that the two-year OS was 24% and two-year relapse rate was 59%. In this study, approximately 30% of patients who achieved CR at the time of HSCT had long-term survival,whereas all who had active disease at the time of HSCT eventually died within one year due to relapse[66].Another retrospective study reported in Korea showed that up-front allogeneic HSCT improves survival outcomes for ANKL patients[67]. In contrast, in a small-scale retrospective study in Japan, of seven patients who underwent allogeneic HSCT and had active disease at the time of HSCT, four achieved CR after HSCT and two of these four patients remained disease-free for more than two years[12]. These results suggest that allogeneic HSCT can provide long-term survival, even in patients with active disease at the time of HSCT.Recently, the impact of allogeneic HSCT for 59 ANKL patients on survival outcomes was reported in Japan[68]. The median OS and PFS were 3.9 and 2.6 months, respectively, which are consistent with the previous data from CIBMTR. The prognosis of patients who relapsed within one year after HSCT was poor,with a median OS of only 1.4 months. In contrast, if patients survived more than one year without relapse,the subsequent five-year OS from one year after allogeneic HSCT was good (85.2%). The prognosis of patients who achieved CR or PR at the time of HSCT was significantly better than that of patients without a response, which was also comparable to a previous finding (five-year OS, 40.6%vs.16.1%,P= 0.046).Interestingly, 15 of 24 patients with primary induction failure at the time of HSCT achieved CR after allogeneic HSCT, and the prognosis of the 15 patients (five-year OS, 32.0%) was almost comparable with that of patients with CR or PR at HSCT (P= 0.95). Therefore, allogeneic HSCT should be considered for all patients with ANKL to improve survival, even for those without response at HSCT. In addition, we should try to develop novel treatments that could provide higher responses for ANKL patients, because the efficacy and response rate of the current treatments are still not satisfactory.

NOVEL AGENTS AND THE POSSIBILITY OF CHEMO-FREE TREATMENTS

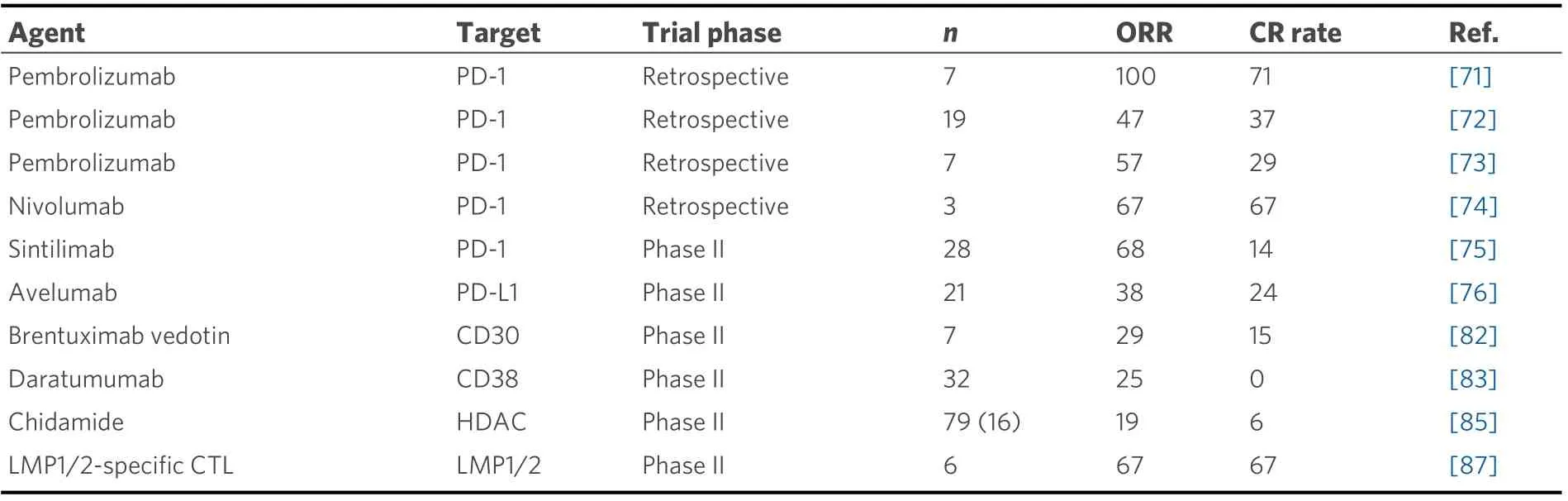

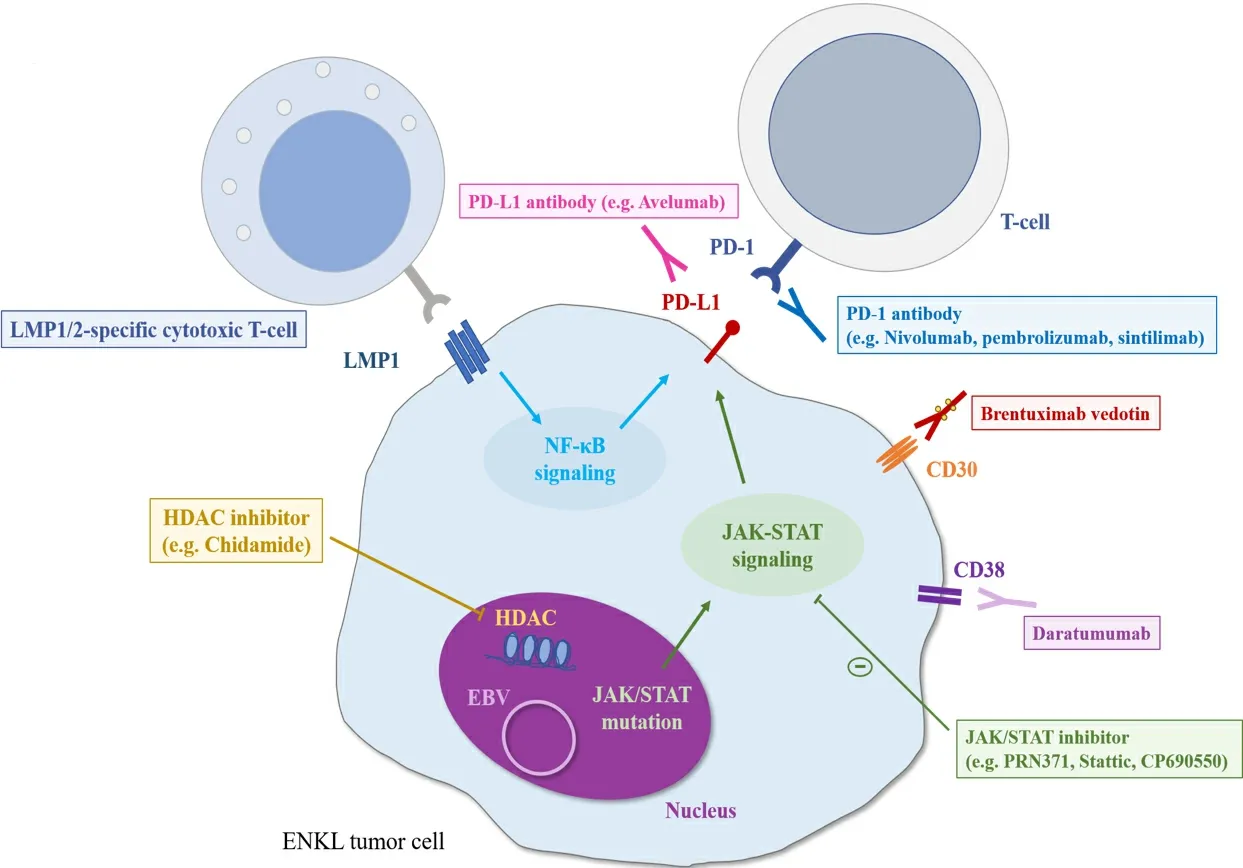

The prognosis of patients with ENKL or ANKL refractory to L-asp-based regimens is extremely poor. A scheme of the associated molecular pathway and the results of clinical trials of promising novel agents for relapsed or refractory ENKL are shown in Figure 2 and Table 2, respectively. A recent study showed that, in patients with EBV-associated lymphoma, including ENKL and ANKL, PD-L1 is frequently expressed in tumor cells owing toPD-L1/PD-L2genetic alterations mainly in the 3’-untranslated regions (UTR)[69,70]. The PD-1/PD-L1 antibody, an immune checkpoint inhibitor, is the most promising treatment for these patients.An excellent response to pembrolizumab at 100 mg (2 mg/kg) once every three weeks in seven patients with ENKL who relapsed or were refractory to L-asp-containing regimens was reported with the ORR of 100%and CR rate of 71%, although this study had a patient selection bias[71]. Similarly, a retrospective analysis of 19 ENKL patients who were treated with pembrolizumab at 3 mg/kg once every three weeks showed that the ORR and CR rate were 47% and 37%, respectively[72]. Next-generation sequencing analysis of the samples of the 19 patients before pembrolizumab initiation in this study revealed that the gene mutation occurred most frequently in the 3’-UTR ofPD-L1(21%), which was the only therapeutic biomarker significantly associated with a good response to pembrolizumab. All ENKL patients (n= 4) with aPD-L1mutation achieved CR with pembrolizumab and sustained the response for more than 30 months. In contrast, PD-L1 expression, evaluated by immunohistochemistry, was not significantly associated with the response to pembrolizumab[72], which was consistent with the results of another study of seven ENKL patients treated with pembrolizumab at 100 mg[73]. In this study, the ORR and CR rate were 57% and 29%, respectively[73].Regarding other immune checkpoint inhibitors, the efficacy of low-dose nivolumab, given at 40 mg every two weeks, was also reported in a small case series[74]. In addition, sintilimab, a novel PD-1 antibody,resulted in a durable response in relapsed or refractory ENKL patients with two-year OS of 78.6% and ORR of 67.9%, as well as a manageable safety profile[75]. In contrast, a slightly lower response rate to avelumab, a PD-L1 antibody, in 21 relapsed or refractory ENKL patients was reported with the ORR of only 38%[76]. In addition, a portion of those without a response rapidly progressed. Further assessments of factors affecting the response to PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies are needed to identify the appropriate population for those treatments. More recently, the combination of several chemotherapies with immune checkpoint inhibitors has also been evaluated and has demonstrated promising results[77-79]. In particular, a phase Ib/II trial of the combination of sintilimab, a PD-1 antibody, and chidamide, a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, in 36 relapsed or refractory ENKL patients showed superior ORR and CR rates of 58% and 44%, respectively[77].Further analyses are warranted to identify the best combination therapy for ENKL patients.

Table 2. Clinical trials of single novel agent for relapsed or refractory ENKL patients

Figure 2. The scheme of molecular pathways and promising treatments for ENKL patients. LMP: Latent membrane protein; EBV:Epstein-Barr virus; HDAC: histone deacetylase.

Several novel targeted agents other than PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies have also been evaluated for their efficacy against ENKL. The clinical efficacy of an anti-CD30 antibody-drug conjugate (brentuximab vedotin) has been reported in two CD30-positive ENKL cases[80,81]. A phase II study for relapsed or refractory CD30-positive non-Hodgkin lymphoma, including seven ENKL patients, showed an ORR of 29% and CR rate of 15%[82]. An anti-CD38 antibody (daratumumab) was also reported to have durable efficacy in a CD38-positive ENKL case[83]. A phase II study of daratumumab monotherapy conducted for 32 relapsed or refractory ENKL patients yielded the ORR of 25% and CR rate of 0% with a median PFS of 55 days[84].Further, the HDAC inhibitor chidamide, which was developed as an oral therapeutic in China, was evaluated in a multicenter, pivotal phase II study of 79 patients with relapsed or refractory T/NK-cell lymphoma, including ENKL patients (20%). The ORR and CR rate of ENKL patients treated with chidamide were 19% and 6%, respectively[85]. In general, ENKL is strongly associated with type II EBV latency, in which latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) and latent membrane protein 2 (LMP2) are expressed[86]. The durable efficacy of autologous LMP1/2-specific cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) has been demonstrated for relapsed or refractory ENKL patients[87]. LMP1/2-specific CTLs were also used as a consolidative therapy for high-risk ENKL patients with a complete response after induction therapy or stem cell transplantation[87,88]. In addition, based on the findings that activation of the JAK-STAT pathway,particularly associated withSTAT3andSTAT5Bmutations, is observed in ENKL tumor cells[89-91], the efficacy of a JAK3-selective inhibitor (PRN371)[92,93]and a STAT3 inhibitor (Stattic)[94]was reported inJAK3-mutated cell lines and a xenograft model andSTAT3-mutated cell lines, respectively. Moreover, a pan-JAK inhibitor (CP-690550) reduced cell viability with increased apoptosis in bothJAK3-mutated and wild-type ENKL cell lines[93]. The clinical efficacies of these agents have not been well studied, and further evaluations are needed.

There are no studies evaluating the efficacy of novel targeted agents for ANKL patients. High sensitivities to a BCL2 inhibitor and a JAK2 inhibitor in vitro were reported[95]. As described previously, because the expression of PD-L1 is high in ANKL, PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies are also promising therapeutic agents for ANKL patients with failed L-asp-containing regimen treatment, and further analysis is warranted.

CONCLUSION

The prognosis of patients with disseminated NK/T cell lymphoma is markedly improving. Recent advances contribute to the improvement, but there remains room for further remedy, particularly for patients with relapsed or refractory NK/T cell lymphoma. Developing novel agents is thus warranted.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Wrote the manuscript: Fujimoto A Revised the manuscript: Suzuki R

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of Interest

Fujimoto A declared that there are no conflicts of interest. Suzuki R received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Chugai Pharmaceuticals, Takeda, Meiji Seika Pharma, MSD, Otsuka,Celgene, Eisai Pharmaceuticals, Abbvie Inc., and Janssen outside the submitted work.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2021.

Journal of Cancer Metastasis and Treatment2021年12期

Journal of Cancer Metastasis and Treatment2021年12期

- Journal of Cancer Metastasis and Treatment的其它文章

- Novel standards and emerging therapies for systemically treatment-naïve clear cell renal cell carcinoma - a rapidly changing landscape

- The contemporary role of metastasectomy in the management of metastatic RCC

- Cancer-directed surgery in malignant pleural mesothelioma: extrapleural pneumonectomy and pleurectomy/decortication

- Intraoperative monitoring of the recurrent laryngeal nerve in surgeries for thyroid cancer: a review

- AUTHOR INSTRUCTIONS