Poor outcomes of delirium in the intensive care units are amplif ied by increasing age: A retrospective cohort study

Wen Gao, Yu-ping Zhang, Jing-fen Jin

1 Nursing Department, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310058, China

2 Nursing Department, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310009, China

KEYWORDS: Intensive care; Delirium; Aging; Mortality

INTRODUCTION

Worldwide trends of increasing life expectancy have resulted in a surge in the elderly population together with the increasing proportion of elderly patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs).[1]In the ICU, delirium is a syndrome manifesting as an acute disturbance and fluctuation of cognition and consciousness characterized by inattention and confusion.[2]It is estimated that delirium could occur in 13% to 66%[3-5]of the elderly patients admitted to ICUs,and delirium itself is a known risk factor for poor outcomes,including prolonged ICU and hospital stay,[5]and in-hospital mortality.[3,6]

The elderly have been found with brain frailty and less physiologic reserve accompanied by infection,surgery and medication, and thus older patients are more vulnerable to ICU stressors and have a poorer prognosis together with higher medical cost in ICU.[7-9]Unfortunately, although previous studies have found that age is an independent predictor for ICU delirium,[10]there is still a lack of literature addressing the role of aging on delirium outcomes. Despite the considerable studies focusing on risk factors for ICU delirium[10]and the clear impact of delirium on patient in-hospital mortality,[4,11]only a few studies have further explored the relationship between aging and outcomes with limited sample sizes and inconsistent findings. One study conducted in the cardiac ICU found that age interacted with sex was associated with patient prognosis,[12]whereas another study with groups (≥65 years) and very elderly (≥80 years) patients showed that the 30-day mortality of delirium patients was not increased signif icantly.[13]

Given the signif icance of age to ICU outcomes, the aim of this study is to investigate the relationship between age categories and in-hospital outcomes among delirium patients admitted to the ICU based on a multi-center database.

METHODS

This study was conducted in accordance with the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) Statement.[14]

Study population and design

This was a retrospective cohort study and samples were extracted from a large multi-center research database(the eICU Collaborative Research Database) with data collected from 208 hospitals from 2014 to 2015 across the USA.[15]All data were deidentif ied to meet the safe harbor provision of the USA Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). The author had completed the required training course and was authorized to access the database for research aims.

Samples were consecutively enrolled from eICU database if they were: (1) ≥18 years old; (2) a record of delirium assessment after admitted to ICU; and (3) firsttime ICU admission. The exclusion criteria were as follows:(1) ICU stay less than 24 hours; (2) delirium prior to ICU admission; and (3) coma during the entire ICU stay.

Measurement of ICU delirium

Delirium was assessed every eight or twelve hours per day and was considered and documented as delirium positive using the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU).[16]The CAM-ICU is a reliable and validated tool for nurses to identify delirium in critical patients, and contains four parts including acute onset or fluctuating course, inattention, altered level of consciousness and disorganized thinking.[17]Delirium was def ined as at least one documented delirium positive from the nursing chart during the whole ICU stay.[18]

Clinical characteristics and data extraction

Demographic characteristics (age, sex, and ethnicity), medical history (cognitive impairment,hypertension, diabetes, stroke), admission information(ICU type, urgent admission), Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IV score,ICU condition (mechanical ventilation, metabolic acidosis, sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome[ARDS]), sedatives (dexmedetomidine, propofol and benzodiazepines), ventilation-free days during hospitalization, and status at both ICU and hospital discharge were extracted from the database. Minutes from ICU admission till discharge were retrieved and computed into days as the length of stay (LOS) in ICU and hospital. Due to the deidentif ied records of age over 89 in the database, patients were classif ied into non-aged(<65 years), young-old (65-74 years), middle-old (75-84 years) and very-old (≥85 years) groups. The primary outcomes were ICU and hospital mortalities, defined as the status of patient survival (expired or survived) at the time of ICU or hospital discharge. The secondary outcomes were the ventilation-free days and LOS in ICU and hospital.

Sample size

According to the sample size rules in Cox regression,[19]at least 1,460 samples were needed to achieve 90% power at 0.05 significance level adjusted for an anticipated mortality rate of 0.08. In this study,we enrolled 3,931 samples which were adequate for detecting differences between groups.

Statistical analysis

For descriptive statistics, mean with standard deviation(SD) for normally-distributed continuous variables,medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for abnormallydistributed continuous variables, and counts and percentages for categorical variables were presented. The ICU and hospital mortality rates were compared using Chi-square test and Bonferroni test. One-way analysis of variance(ANOVA) and least significance difference (LSD) posthoc test were performed to compare differences of LOS and ventilation-free days between age groups. Covariates were selected from sex, medical history, APACHE IV score,mechanical ventilation, metabolic acidosis, sepsis, ARDS and use of sedatives with a significant hazard ratio (HR)from the univariate Cox regression analysis. A multivariate Cox regression model was then built to investigate the independent effect of aging on ICU and hospital mortalities.

Only a few missing values were found in ethnicity(4.4%) and APACHE IV score (0.07%). Missing values in ethnicity were categorized as unknown, and multiple imputations were performed to replace the missing values in APACHE IV score. Data extraction and management were performed using PostgreSQL (version 10.0) and Navicat (version 12.0.18). SPSS software (version 24.0)was used for statistical analysis. Statistical significance was determined as aP-value <0.05.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics of patients with ICU delirium

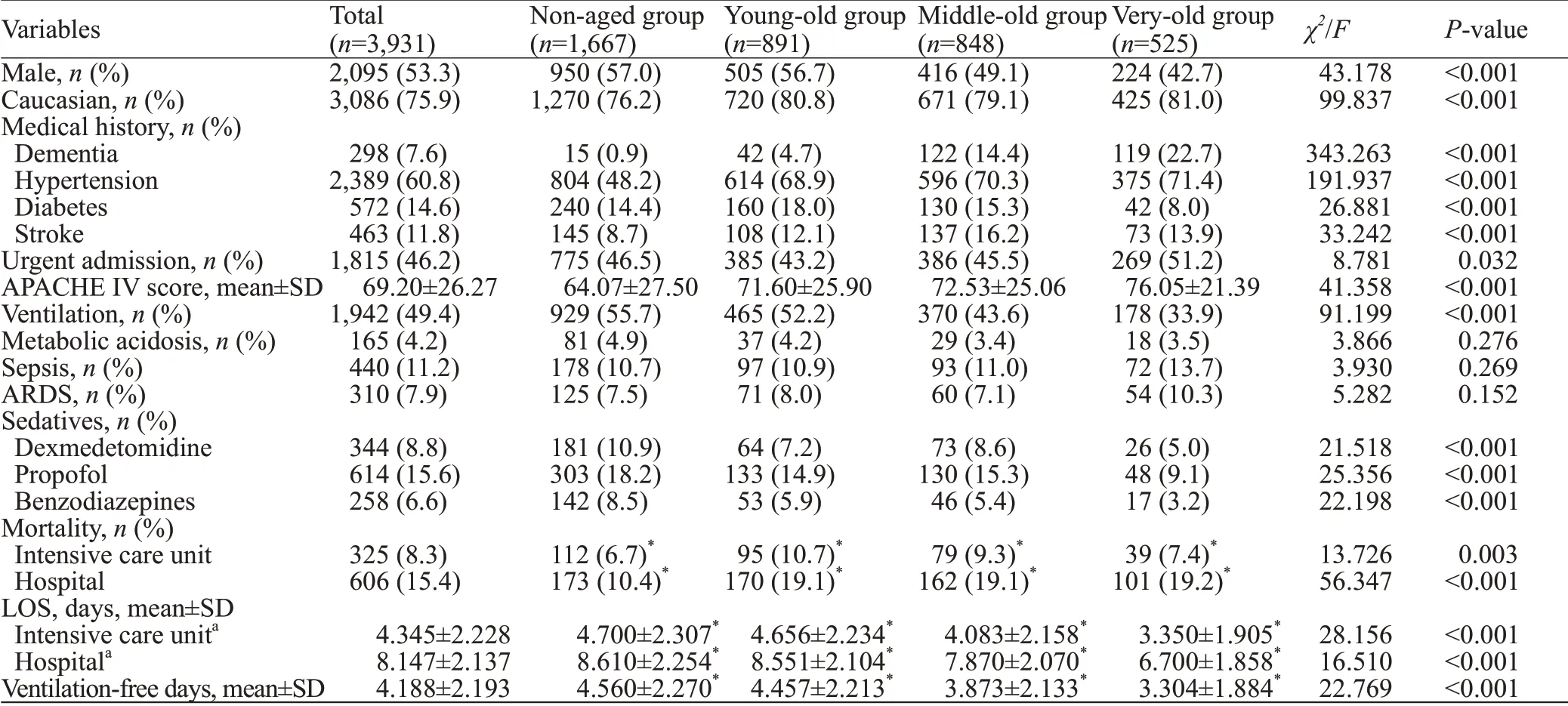

A total of 36,216 positive CAM-ICU records from 6,127 patients were screened and 3,931 patients from 44 hospitals were included according to the inclusion criteria.There were 1,667 (42.4%) non-aged, 891 (22.7%) youngold, 848 (21.6%) middle-old, and 525 (13.4%) very-old patients. The elderly patients (≥ 65 years) showed higher APACHE IV scores (72.98±24.66,P<0.001) compared with non-aged patients (63.07±27.50), together with more comorbidities but less use of mechanical ventilation(44.7% vs. 55.7%,P<0.001), propofol (13.7% vs. 18.2%,P<0.001), dexmedetomidine (7.2% vs. 10.9%,P<0.001),and benzodiazepines (5.1% vs. 8.5%,P<0.001). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Mortality rate and LOS in ICU and hospital

The ICU mortality rate was 8.3%, and the inhospital mortality rate was 15.4%. Patients aged ≥65 years had signif icantly higher mortality rates in both ICU(χ2=9.157,P<0.001) and hospital (χ2=56.340,P<0.001)than the non-aged patients. The young-old group had the highest rate of ICU mortality (10.7%), while all of the three aged groups had a higher rate of hospital mortality, compared with the non-aged group. The ICU and hospitalization LOS were 4.03 (2.33-7.65) days, and 9.02 (5.63-15.15)days respectively. There were significant differences in ventilation-free days in the hospital as well as LOS in ICU and the hospital between age groups after log-normalization(Table 1).

Impact of age groups on patient outcomes

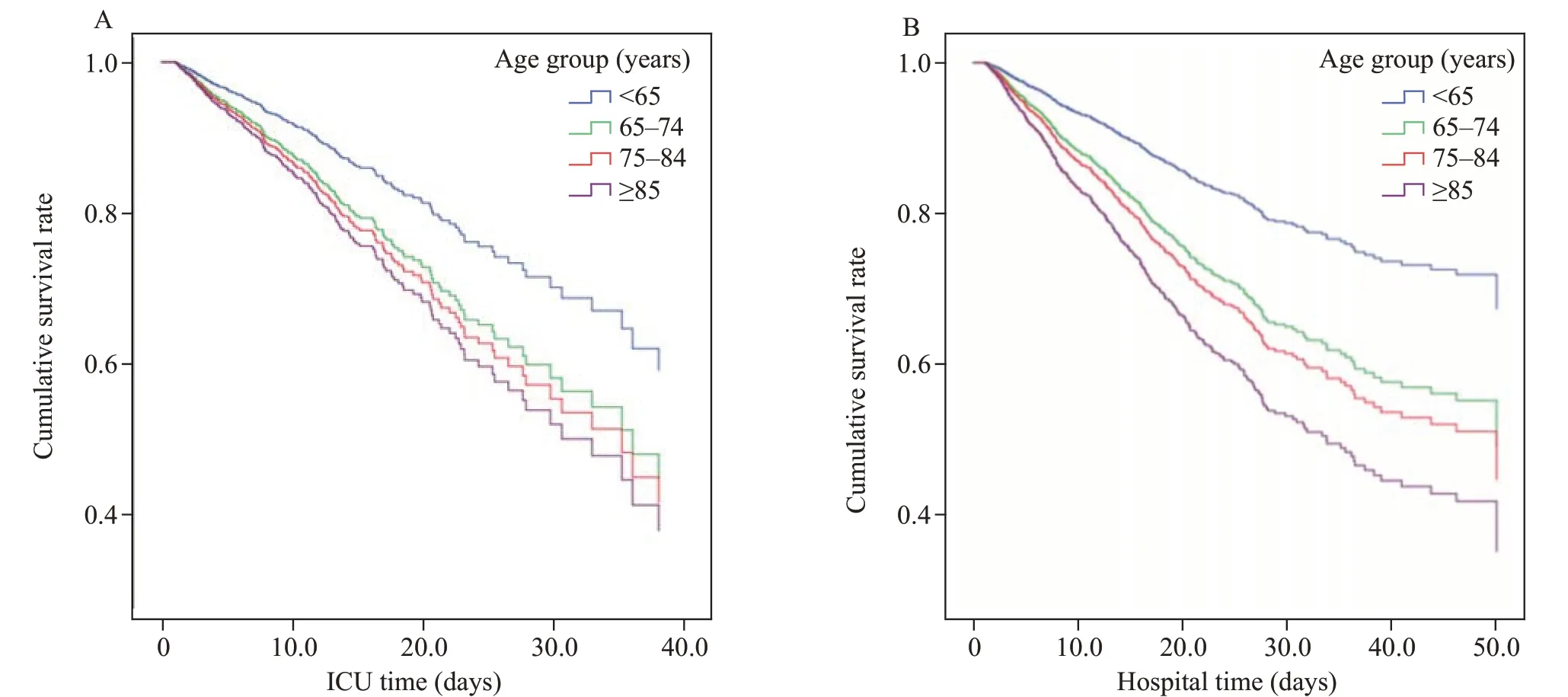

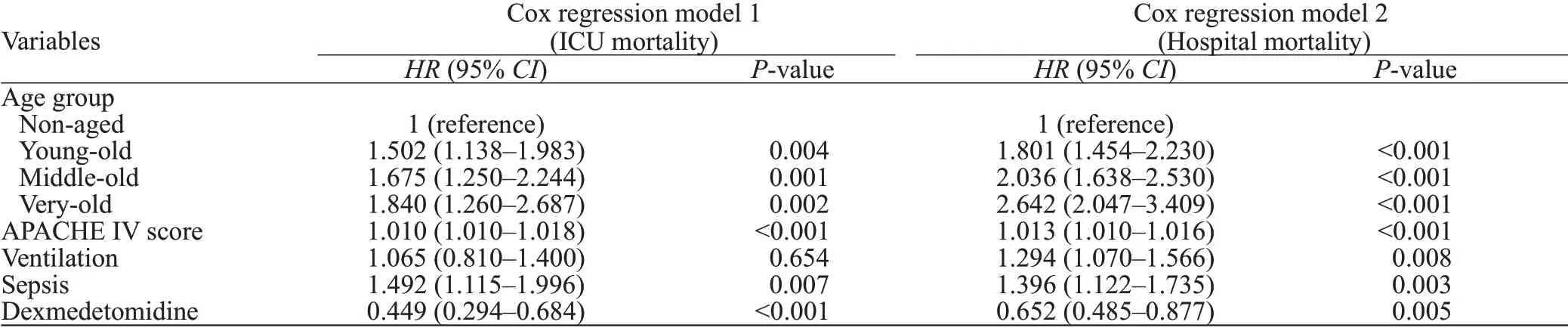

Univariate analysis showed that age group was an independent risk factor of ICU mortality (HR=1.69, 1.79,and 2.16 for young-old, middle-old, and very-old groups,respectively,P<0.001) and hospital mortality (HR=1.92,2.12, and 2.91 for young-old, middle-old, and veryold groups, respectively,P<0.001) in the univariate Cox regression. The APACHE IV score, ventilation, and sepsis were found as independent risk factors for ICU and hospital mortalities, and use of dexmedetomidine was associated with decreased risk of ICU mortality and hospital mortality.Apart from the age group, all these variables were adjusted as covariates in the multivariate Cox regression model and details of the regression model are presented in Table 2.Survival curves in Figure 1A and Figure 1B also display the estimated survival probability for four different age groups of patients with delirium in ICU, showing the association between increased age groups and a higher risk of death both in ICU and hospital.

Figure 1. Association between age groups and mortality among ICU delirium patients, using ICU death (A) and hospital death (B) as primary events. The curves were adjusted for APACHE IV score, ventilation, sepsis and use of dexmedetomidine, and stratif ied by age groups.

DISCUSSION

ICU delirium is widely regarded as a major neurologic complication and seriously affects the prognosis of critical patients. In this large, multicenter cohort electronic database, aging was found to be an independent factor for poor prognosis of patients with delirium in ICU. The results showed that death in ICU and hospital increased with aging even after controlling the effects of critical conditions and sedatives. Although advanced age is a known predictor of delirium occurrence in ICU, to our knowledge this is the first study with a large dataset reporting specifically on the impact of different age groups on delirium patients’outcomes to promote better stratif ied intervention.

Compared with non-aged patients, there were more females and Caucasians in the elderly groups (≥65 years),and patients in the elderly group had more comorbidities,including dementia, hypertension, diabetes, and history of stroke. Also, patients in the elderly groups had higher APACHE IV score at ICU admission, and more than half of the very-old patients (51.2%) were admitted emergently. This finding indicated that the condition of the elderly patients admitted to ICU was more serious.[20]However, there were no significant differences between age groups in the diagnosis of metabolic acidosis, sepsis,or ARDS. Concerning that all these syndromes are risk factors for ICU delirium,[10,21]the selection of deliriousspecif ic population may have resulted in this f inding.

The analysis showed that patients above 75 years received much less ventilation but fewer ventilationfree days during hospitalization, and the very-old patients received less treatment with sedatives, including dexmedetomidine, propofol, or benzodiazepines. This is in accordance with reported findings[22,23]indicating that above a certain age the patients or their surrogates are reluctant to use ventilation and prefer withholding invasive interventions in the clinical practice. But for those mechanically ventilated patients, they may need more time to achieve successful weaning and have prolonged ventilation duration.[24]This finding may be important for the decision process for the caregivers on how to allocate resources and develop ventilation plans.

Table 1. Characteristics of ICU delirium patients in different age groups

Table 2. Cox regression model for mortality

The differences in outcomes were found in both mortalities and LOS in ICU and hospital. For the elderly,cognitive impairment is often combined with other age-related diseases, including chronic organ disease and senescence, indicating impaired physiologic and functional reserve.[25]Apart from the advancement of mortality rate,[26]critical patients with increased age were also found with more comorbidities and frailty in the early stage after ICU admission from other studies.[27,28]Thus all these predisposing factors could contribute to a worse prognosis of the elderly in ICU. The mortality rate in our study is not as poor as those from the previous studies conducted in the very elderly patients (≥90 years),[29]and this may be connected with the exclusion criteria that patients with persistent coma or stay in the ICU for less than 24 hours were excluded from this study.

Existing studies often refer to age as a single risk factor for delirium, but the old patient group is rarely studied as a singular group for clinical outcome analysis and the f indings are inconsistent.[30,31]We found that aging was an independent risk factor for both ICU and hospital deaths even after controlling APACHE score and ICU treatment factors. This is in accordance with previous studies which have found that older patients (≥65 years)were susceptible to have physical and cognitive declines following critical illness,[32]sudden clinical deterioration with a change in goals of care,[33]and limitation of treatment.[34]However, in a cohort study of sepsis, age was only found as an independent mortality-associated risk factor in the patients older than 80 years.[34]The possible reason may be the differences in the population characteristics. The very-old patients had a larger number of admissions underlying the worse conditions, and we only included the f irst-time admitted patients for all age groups.

Noticeably, we found that the impact of aging remained after ICU discharge and got further enlarged on the prognosis during the patient’s entire hospitalization.This is in accordance with previous studies exploring outcomes induced by delirium. Atramont et al[35]found that aging was associated with an increased risk of longterm mortality with a remarkable risk among the veryold patients older than 80 years. Instead of temporary inf luences, delirium is related to a slower rate, and poor quality of recovery[36]and thus could trigger a poor outcome even after ICU discharge.

Although the pathophysiology of ICU delirium remains unclear, existing studies related to ICU delirium mechanism have found that factors indicating systematic inf lammatory response, neuronal dysfunction and cortisol responses[37]are related to ICU delirium occurrence. Along with aging, endothelial function and cerebral perfusion get impaired,[38]the capacity of the brain to transmit signals and communicate reduces,[39]the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulates,[40]and inflammatory response alters.[41]Therefore, it is possible that ICU delirium pathways are moderated by aging and related to death in ICU and hospital, as agerelated vulnerability factors mentioned above have also been found in a relationship with in-hospital mortality.[42,43]

Another three independent risk factors for in-hospital death, including APACHE score, sepsis, and ventilation,were identified, and dexmedetomidine was found to be an independent protective factor of both ICU and hospital mortalities. This result is in accordance with findings from previous studies of delirium risk factors.[10]Elevated APACHE IV score indicates an association between critical condition and mortality, and APACHE score has been found as a risk factor for the prognosis of different critical populations in ICU.[44,45]Older patients who require prolonged ventilation have a higher risk of mortality and heavier burdens of treatment.[24,46]Also, for patients older than 70 years, they have been found to have an increased risk of death due to sepsis.[47]For dexmedetomidine as a short-acting intravenous anesthetic agent, it has been found to be associated with shorter duration of ventilation and less delirium.[48]

This study has several limitations. First, it was a retrospective study based on a large electronic database,so only delirium occurrence was available in the dataset instead of severity. Second, as the age of the very-old patients was documented as ≥85 years in the original dataset, we could only classify the age ranges and treat age as a categorical variable. Despite these limitations, the strength of this study was based on a multicenter collection of data and a large number of ICU delirium patients. Furthermore, we also controlled several covariates concerning patient conditions to prevent confounding. Therefore, this study identified age-stratified populations at a high risk of death among delirious patients and provided evidence for ICU physicians and nurses to make risk stratif ication of delirious patients and targeted care plans to allocate caregivers better.

CONCLUSIONS

Aging is independently associated with poor inhospital outcomes of ICU delirium patients. Early identif ication of ICU delirium patients with risk of poor prognosis is of vital significance and could allow the focused application of limited ICU resources to improve patient survival. Further studies are needed to explore the underlying pathophysiological interactions between delirium and aging.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Sheila Alexander for her advice to part of the study and the computer engineer Le Zhang for sharing syntax.

Funding:This study was supported by the Nursing Funding of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (2019[19]-3).

Ethical approval:Not applicable. The analysis was authorized by the eICU Collaborative Research.

Conf licts of interests:The authors have no conf licting interests in this study.

Author contributions:WG implemented the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. YPZ guided the statistical analysis and revised the manuscript. JFJ designed the study and substantively revised the manuscript.

World journal of emergency medicine2021年2期

World journal of emergency medicine2021年2期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Does shifting to professional emergency department staffing affect the decision for chest radiography?

- Effectiveness of an educational program on improving healthcare providers’ knowledge of acute stroke: A randomized block design study

- Role of urine studies in asymptomatic febrile neutropenic patients presenting to the emergency department

- Violence toward emergency physicians: A prospectivedescriptive study

- Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids in immunocompetent patients with septic shock

- Blood eosinophils and mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: A propensity score matching analysis